Abstract

The collection of small aliquots of bone marrow (BM), followed by ex vivo expansion for autologous transplantation may be less morbid, and more cost-effective, than typical BM or blood stem cell harvesting. Passive elimination of contaminating tumor cells during expansion could reduce reinoculation risks. Nineteen breast cancer patients underwent autotransplants exclusively using ex vivo expanded small aliquot BM cells (900-1200 × 106). BM was expanded in media containing recombinant flt3 ligand, erythropoietin, and PIXY321, using stromal-based perfusion bioreactors for 12 days, and infused after high-dose chemotherapy. Correlations between cell dose and engraftment times were determined, and immunocytochemical tumor cell assays were performed before and after expansion. The median volume of BM expanded was 36.7 mL (range 15.8-87.0). Engraftment of neutrophils greater than 500/μL and platelets greater than 20 000/μL were 16 (13-24) and 24 (19-45) days, respectively; 1 patient had delayed platelet engraftment, even after infusion of back-up BM. Hematopoiesis is maintained at 24 months, despite posttransplant radiotherapy in 18 of the 19 patients. Transplanted CD34+/Lin−(lineage negative) cell dose correlated with neutrophil and platelet engraftment, with patients receiving greater than 2.0 × 105 CD34+/Lin− cells per kilogram, engrafting by day 28. Tumor cells were observed in 1 of the 19 patients before expansion, and in none of the 19 patients after expansion. It is feasible to perform autotransplants solely with BM cells grown ex vivo in perfusion bioreactors from a small aliquot. Engraftment times are similar to those of a typical 1000 to 1500 mL BM autotransplant. If verified, this procedure could reduce the risk of tumor cell reinoculation with autotransplants and may be valuable in settings in which small stem cell doses are available, eg, cord blood transplants.

Bone marrow (BM) harvesting and peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) mobilization and collection procedures needed for autologous transplantation, are expensive and associated with moderate morbidity.1,2 The collected cells can contain contaminating tumor cells that may contribute to relapse.3-5 Transplantation of cells from small aliquots of bone marrow stem cells (BMSC), expanded ex vivo, may both decrease collection morbidity and the risk of tumor cell reinoculation.

In the late 1970s, Dexter and colleagues6 determined that a preformed stromal cell layer, intermittent refeeding with media, and constant gas exchange were requirements for optimal ex vivo BMSC expansion. However, a rapid loss of the human primitive stem cell pool occurred, and all cell growth ceased by 12 weeks.7Subsequent studies demonstrated that frequent medium and constant gas exchange, and the use of BM mononuclear cells led to up to a 20-fold expansion of committed myeloid stem cells (CFU-GM). Primitive stem cells, as measured by long-term culture initiation cells (LTCIC), also expanded up to 8-fold when exogenous cytokines were added.8-11 These studies verified the importance of the stromal cell layer that developed from the BM cell inoculum and produced stimulators of hematopoiesis such as interleukin 1 (IL-1), interleukin 6 (IL-6), stem cell factor, and leukemia inhibitory factor.12-14 Optimal growth of the BMSC was subsequently seen if exogenous growth factors were added.9,10,14Importantly, expansion of primitive stem cells did not occur if only selected CD34+ stem cells were used to initiate the cultures.12

Murine studies subsequently indicated that ex vivo expanded BMSC that had been cultured with stem cell factor and IL-1 could successfully rescue lethally irradiated animals, with donor cells seen in the recipients for more than 1 year.15 On the basis of these findings and the development of a computerized, automated closed-system for cell growth (AastromReplicell System™; Aastrom Biosciences; Ann Arbor, MI),9,16 Phase I human clinical trials began. Ex vivo expanded BMSC were infused with conventional BM (unexpanded) cells.17 There was no toxicity from the infused cells and a potential benefit as measured by shortening of hospital stays, time-to-platelet engraftment and days of febrile neutropenia when 60% or more of a standard engrafting cell dose of 1 × 105 CFU-GM/kg were infused. In addition, subsequent in vitro studies verified that passive tumor cell elimination during expansion occurs when BM, contaminated with tumor cells, was expanded in this system.18

On the basis of these reports, we conducted a phase II study of ex vivo expanded BMSC as the sole source of hematopoietic cell rescue after ablative chemotherapy in patients with advanced carcinoma of the breast. Endpoints included time to engraftment, tumor cell depletion, and the reliability of this system for BMSC expansion.

Materials and methods

Selection of patients

Patients with stage II, with more than 10 involved axillary nodes and stage III/IV carcinoma of the breast, were eligible for high-dose chemotherapy in this Institutional Review Board approved clinical trial. Up to 2 regimens of chemotherapy and radiotherapy were permitted before entry. Patients with stage IV disease were required to have chemotherapy responsive, low tumor burden disease. Histologically normal bilateral BM aspirates and biopsies with a minimum cellularity of 30%, no comorbid illnesses and a normal cardiac ejection fraction were required. A delay of 4 weeks from previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy was also required.

Bone marrow harvesting and cryopreservation

BM was aspirated from both the anterior/posterior iliac crests in the operating room, with initial aspirates collected for expansion. For these aspirates, 2.5 to 3.0 mL of BM was collected from each bone puncture, comprised of 2 aspirations at different depths. Approximately 75 mL of BM was collected in this fashion for expansion processing. Then, 1.5 × 108 additional nucleated cells/kg were harvested19 and cryopreserved as a back-up, to be infused should neutrophil or platelet engraftment be delayed.

Ex vivo expansion

The BM mononuclear cells were expanded for 12 days in single pass, stromal-based AastromReplicell closed-system perfusion culture chambers, using a computer-directed process of gas and medium flow, determined by preclinical studies to maximize hematopoietic cell growth and stromal layer development. The growth surface area of the culture chamber is 750 cm2. From 2.25 to 4.50 × 108 BM mononuclear cells, separated using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden), were placed into each of 3 or 4 single-use cassettes (culture chamber and disposable fluid pathway). Oxygen (20%), carbon dioxide (5%), and nitrogen (75%) were continuously exchanged through a gas-permeable, liquid-impermeable membrane covering each culture area. The cells were expanded in long-term bone marrow culture medium (Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY), consisting of IMDM, 10% fetal bovine, and 10% horse sera, supplemented with final concentrations of GM-CSF-IL3 fusion protein at 5 ng/mL (PIXY321, Immunex, Seattle, WA), flt3 ligand at 25 ng/mL (Immunex), and erythropoietin at 0.1 U/mL (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA). Hydrocortisone (final concentration 5 × 10-6mol/L), L-glutamine (4 mmol/L), gentamicin sulfate (5 mcg/mL), and vancomycin (20 mcg/mL) were added to the media, because of a well-described incidence of bacterial contamination of marrow. The cell cassette was maintained at 37°C, while the medium reservoir was maintained at 4°C. After 12 days, nonadherent cells were collected along with the adherent cells, which were made tryptic using 0.04% trypsin (Life Technologies Inc, Grand Island, NY). The cells were then washed 4 times with 0.5% human albumin in Normosol R, pH 7.4 (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) using a COBE 2991 cell centrifuge (Cobe BCT, Lakewood, CO) and resuspended at a final volume of 250 mL of the same medium for infusion.

In vitro assays of unexpanded and expanded cells

Total nucleated cell counts and trypan blue viability assays and in vitro assays for myeloid, erythroid, multilineage, and stromal progenitor cells were performed9 as well as limiting dilution LTCIC assays,9 both before and after expansion. Cells were also analyzed before and after expansion by flow cytometry (Epix Excel, Coulter, Miami, FL) using monoclonal antibodies to CD11b, CD3, CD15, CD20, CD34, Thy 1, and glycophorin A, along with isotype controls. The combination of CD11b/CD15 rather than CD33 was used to delineate the mature myeloid population. Because of autofluorescence of stromal cells, routine gating of CD34+ cells was difficult in the expanded cell product. Because of this, we used the combined CD34+, but lineage negative (CD34+/Lin−) for T cells, B cells, erythroid cells, and mature myeloid cells (CD34 positive and CD3/CD20/CD11b/CD15/Gly-A negative), as our measure of CD34 content in both the pre- and postexpansion assays. As a comparison, this assay gave similar results to the CD34 assay recently endorsed by the International Society of Hematotherapy and Graft Engineering (data not shown). CD34+ expression on nonhematopoietic cells was excluded by gating according to cell size and density, and 50 000 events were analyzed. In additional preclinical experiments, the fraction of CD34+/Lin− cells that were also CD38− was 1.03%. Routine microbiologic cultures were obtained both before and after expansion, and on day 10 of incubation, from the effluent medium line of the cell cassette. The expanded cells were released for transplantation if greater than 1.6 × 109 cells were harvested with a viability of greater than 80%, and the day 10 microbial cultures were negative.

Tumor contamination assays

Detection of minimal residual disease in pre- and postexpansion samples was evaluated according to the immunocytochemical method of Franklin et al,20 which is able to detect 3 tumor cells in a background of 106 normal hematopoietic cells. Before immunocytochemical assay, cells were washed with medium-199 (Gibco Laboratories) containing 10% heparin and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 25% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/mL. Cytospins of 5 × 105 cells were prepared using a Cyto-Tek centrifuge (Miles Scientific, Elkhart, IN). After fixing in acetone/methanol/formalin (45%/45%/10%) for 20 minutes, slides were stained with the Bre-3 antibody, which targets mucin-a expressed by breast cancer cells plus the anticytokeratin monoclonal antibody cocktail (AE1/AE3, Signet Laboratories, Dedlam, MA). The slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin. A total of 10 stained slides were examined per specimen using a standard binocular light microscope.

High-dose chemotherapy and transplantation of expanded cells

All patients were treated with the STAMP V high-dose chemotherapy carboplatin (800 mg/m2), thiotepa (500 mg/m2), and cyclophosphamide (6000 mg/m2) as previously described.21 The expanded cells were infused over 60 minutes, unfiltered, 72 hours after the chemotherapy was completed. All patients received G-CSF (Amgen) subcutaneously at a dose of 10 μg/kg daily starting 4 hours after cell infusion and continuing until the neutrophil count rose above 1 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days. Supportive care consisted of prophylactic fluconazole, norfloxacin, and acyclovir, as well as platelet transfusions for counts less than 20 × 109/L. The back-up cryopreserved cells were to be infused if the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) had not reached 500/μL by day 21 or the platelet count had not reached 20 000/μL by day 28 after transplant. Hospital discharge occurred once the ANC had reached 500/μL; or an ANC greater than 100/μL, with the patients being afebrile for 48 hours. Radiation therapy was permitted per center routine as consolidation therapy after transplant.

Analysis of engraftment correlates

Primary endpoints were reliability of the culture system, time to engraftment of neutrophils and platelets, toxicities from the infused cells, the number of platelet transfusions, and days of fever with neutropenia. Engraftment of neutrophils and platelets was defined respectively as the first of 7 days that the ANC rose above 0.5 × 109/L, and the first day the platelet count rose above 20 × 109/L, without transfusions. Analyses of time to engraftment were correlated to nucleated and stem cell dose per kilogram, both before and after expansion, using curve-fitting methods that gave the best correlation coefficient. The significance of the correlation was determined at 95% confidence interval using a 2-tailed Student t test.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are shown in Table1. We treated a total of 19 patients, of whom only 2 had high-risk stage II disease. Of the 10 patients with stage IV disease, 8 had relapsed after prior adjuvant chemotherapy and 2 presented with metastatic disease. None had bone scan abnormalities in their pelvic bones, and as per center selection policy for breast cancer transplants, all were transplanted in either a complete remission (CR) or near CR. Their median BM cellularity was 30% and none had histologic evidence of tumor involvement at entry.

Patient characteristics

| Number transplanted | 19 |

| Stage of disease at transplant | |

| II | 2 |

| III | 7 |

| IV | 10 |

| Median age (range) | 45 (32-54) |

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens | |

| 1: | 15 |

| 2: | 4 |

| Median number of chemotherapy cycles | 4 |

| Number receiving prior radiotherapy | 2 |

| Number transplanted | 19 |

| Stage of disease at transplant | |

| II | 2 |

| III | 7 |

| IV | 10 |

| Median age (range) | 45 (32-54) |

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens | |

| 1: | 15 |

| 2: | 4 |

| Median number of chemotherapy cycles | 4 |

| Number receiving prior radiotherapy | 2 |

Analyses of expanded cells

Analyses of the BM cells collected for expansion are shown in Table2. Twelve of the 19 patients received the expanded cells from a starting inoculum of 9 × 109BM mononuclear (MNC) cells, and the remainder from 12 × 109 MNC cells in an attempt to explore cell dose per engraftment interactions. This represents a median starting marrow aliquot for the entire patient group of 36.7 mL (range 15.8-87.0) and a medium cell dose of 13.0 × 106/kg (range 9.2-21.4). The mean percentage of CD34+/Lin− cells in the inoculum was 2.6%, and the preexpansion CD34 dose per kilogram was 3.5 (range 1.5-7.2) × 105/kg.

Preexpansion bone marrow cell characteristics

| % Marrow cellularity preharvest | 30 (30-50) |

| Nucleated cells/mL harvested (×106) | 47.8 (31.0-77.5) |

| % Mononuclear cells | 50.8 (38.4-74.2) |

| % CD34+/Lin− in inoculum | 2.5 (1.6-3.9) |

| Mononuclear cell dose/kg expanded (×106) | 13.0 (9.2-21.4) |

| Milliliters of marrow used for expansion | 36.7 (15.8-87.0) |

| % Marrow cellularity preharvest | 30 (30-50) |

| Nucleated cells/mL harvested (×106) | 47.8 (31.0-77.5) |

| % Mononuclear cells | 50.8 (38.4-74.2) |

| % CD34+/Lin− in inoculum | 2.5 (1.6-3.9) |

| Mononuclear cell dose/kg expanded (×106) | 13.0 (9.2-21.4) |

| Milliliters of marrow used for expansion | 36.7 (15.8-87.0) |

Values expressed as medians (ranges).

The cell expansion data are shown in Table3. There was a median 4.6-, 11.0-, and 0.94-fold expansion of nucleated cells, CFU-GM and CD34+/Lin− cells in the expanded product. Of the 19 patients, 7 had expansion of CD34+/Lin− cells that averaged 2.7-fold. No unique clinical features, eg, stage or amount of prior therapy were noted in this patient subgroup. There was a 43.1-fold increase in stromal progenitor cells as measured by CFU-F. LTCIC cells were also expanded by a median value of 20%. The mean number of nucleated cells and CD34+/Lin− cells infused per kilogram were 55(32-98) × 106/kg and 3.4(0.42-11.8) × 105/kg, respectively. There was a decline in absolute numbers of B and T cells during expansion to 68% ± 15% and 82% ± 23%, respectively, of inoculation numbers.

Cell expansion data

| . | Inoculum . | Postexpansion . | Fold Expansion . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mononuclear cells × 106 3-150 | 900 1200 | 4307 (2524-6277) 5064 (3265-6931) | 4.8 (2.8-6.9) 4.2 (2.7-5.8) |

| CFU-GM × 106 | 3.1 (0.9-9.6) | 33.4 (11.9-74.8) | 11.0 (5.0-65.2) |

| CFU-F × 103 | 55.6 (11.3-126.9) | 2397.7 (244.5-5629) | 43.1 (9.0-312.7) |

| CD34+/Lin− × 106 | 26.5 (14.4-49.5) | 24.7 (2.5-73.6) | 0.9 (0.13-2.11) |

| LTCIC × 103 | 74.0 (32.4-518) | 91.0 (9.9-370.5) | 1.2 (0.1-2.9) |

| . | Inoculum . | Postexpansion . | Fold Expansion . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mononuclear cells × 106 3-150 | 900 1200 | 4307 (2524-6277) 5064 (3265-6931) | 4.8 (2.8-6.9) 4.2 (2.7-5.8) |

| CFU-GM × 106 | 3.1 (0.9-9.6) | 33.4 (11.9-74.8) | 11.0 (5.0-65.2) |

| CFU-F × 103 | 55.6 (11.3-126.9) | 2397.7 (244.5-5629) | 43.1 (9.0-312.7) |

| CD34+/Lin− × 106 | 26.5 (14.4-49.5) | 24.7 (2.5-73.6) | 0.9 (0.13-2.11) |

| LTCIC × 103 | 74.0 (32.4-518) | 91.0 (9.9-370.5) | 1.2 (0.1-2.9) |

Medians (ranges).

Twelve patients transplanted with starting inoculum of 900 × 106, 7 patients with 1200 × 106 cells.

Clinical outcome

All 19 patients received their expanded cells as planned, with all expansions exceeding minimum expansion and viability requirements. All microbiologic cultures of the expanded cells were negative and there were no WHO grade 2 or greater toxicities from their infusion. No patient had septicemia before engraftment and there were no grade 2 or greater nonhematopoietic transplant–related toxicities seen in any patient.

The median (range) times to ANC and platelet engraftment were 16 (13-24) and 24 (18-45) days, respectively (Table4). Engraftment of neutrophils was sustained in all patients at follow-up times up to 30 months. One patient (patient 7) failed to engraft platelets by day 35 after transplant and received her cryopreserved marrow cells without incident. Despite the infusion of these cells, she failed to engraft platelets to greater than 100 × 109/L. Three others without ANC (1 patient) and/or platelet (3 patients) engraftment occurring before day +21 and +28, respectively, refused their back-up BM infusions. All engrafted within a week of these endpoints, and have had durable engraftment of all cell lineages. Eighteen (95%) of the patients received planned consolidative radiotherapy to the ipsilateral chest wall and axilla (stage II and III disease), or to single sites of metastatic disease after transplant, starting approximately day +60 after transplant. In several patients, a temporary drop in platelets, never requiring transfusions, was seen after the radiotherapy was completed. No patient has lost her graft at a median follow-up time of 24 months (range 20-30 months) for the entire group. Fourteen patients remain alive, with deaths due to progressive disease in patients with stage IV disease (4/10) and stage III (1/7) at 5 to 15 months after transplant.

Engraftment data

| Engraftment Parameter . | Median Days to Engraftment (Range) . |

|---|---|

| ANC > 500/μL | 16 (13-24) |

| ANC > 1000/μL | 18 (15-28) |

| Platelets > 20 000/μL | 24 (19-45) |

| Platelets > 50 000/μL | 33 (24-66) |

| Platelets > 100 000/μL4-150 | 48 (26-364+) |

| Engraftment Parameter . | Median Days to Engraftment (Range) . |

|---|---|

| ANC > 500/μL | 16 (13-24) |

| ANC > 1000/μL | 18 (15-28) |

| Platelets > 20 000/μL | 24 (19-45) |

| Platelets > 50 000/μL | 33 (24-66) |

| Platelets > 100 000/μL4-150 | 48 (26-364+) |

ANC = Absolute neutrophil count.

18/19 received radiation therapy starting around day +60.

Circulating neutrophils were seen for the first 2 to 3 days after the infusion of the expanded cells in most patients, and may have contributed to the fact that 68% had 2 or fewer days of posttransplant fever, despite the median time to ANC engraftment of 16 days. In fact, all but 1 patient had an ANC on day +1 after transplant greater than 100/μL, and in several patients, the ANC on the day after transplant was higher than on the actual day of transplant (median [ranges] for day 0 and day +1 were 604 [152-1710] and 282 [79-2000] μL/mL). The median time to discharge from the hospital was 12 days after transplant (range 9-16) at which time all patients were afebrile.

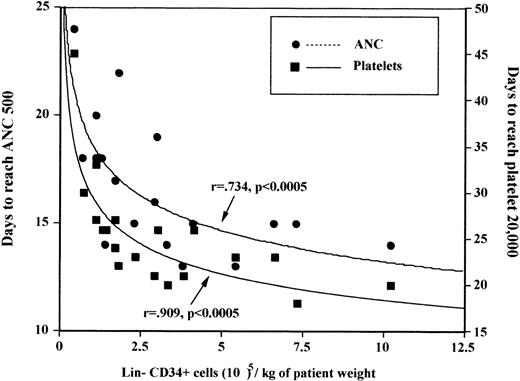

All 12 patients receiving greater than 2 × 105CD34+/Lin− cells per kilogram of expanded cells engrafted platelets by day 28 in contrast to only 4/7 of those who received at least 2 × 105/kg. The most rapid platelet engraftment occurred in those who received either at least 5 × 105 CD34+/Lin−expanded cells per kilogram (median 20 days) or those in whom any expansion of CD34+/Lin− was seen (median 21 days). There was no correlation of either pre-and postexpansion nucleated cells, CFU-GM, multilineage committed progenitor cells, or LTCIC cell doses per kilogram to time to engraftment of neutrophils. There was a correlation between ANC engraftment and postexpansion CD34+/Lin− cell dose per kilogram (P = .0005)(Figure 1). Platelet engraftment correlated only with CD34+/Lin− postexpansion cell dose (P < .0005) and total nucleated cell dose (P = .03) infused, and there was a borderline correlation to the number of stromal cells infused (CFU-F;P = .08). Although engraftment correlated with the number of postexpansion CD34+/Lin− cells per kilogram, it did not correlate with the number of preexpansion CD34+/Lin− cells per kilogram.

Correlation of engraftment with CD34+/Lin− ex vivo cell dose per kilogram transplanted: days to ANC > 500/μL, and platelets > 20 000/μL.

(ANC = absolute neutrophil count.)

Correlation of engraftment with CD34+/Lin− ex vivo cell dose per kilogram transplanted: days to ANC > 500/μL, and platelets > 20 000/μL.

(ANC = absolute neutrophil count.)

Tumor contamination assays

Of the 19 preexpansion samples, 1 (5.2%) was positive at a concentration of 4 tumor cells per 106 marrow mononuclear cells. This patient's expanded cells and those of the remaining patients were tumor cell-free at the sensitivity of 3 tumor cells per 106 (90% confidence level).

Discussion

Using this stromal-based, continuous perfusion method of BMSC expansion, we have been able to achieve engraftment in patients after high-dose chemotherapy with a thiotepa-based (500 mg/m2) regimen,21 starting from a median volume of BM of only 36.7 mL. Although this regimen has not been conclusively demonstrated to be ablative, several trials have indicated that the maximally tolerated dose of thiotepa is 100 to 180 mg/m2, due to prolonged myelosuppression.22,23 One of 19 patients required the infusion of her “back-up” BM cells, yet still did not engraft platelets to greater than 60 000/μL, suggesting preexisting stem cell damage. Engraftment times for neutrophils and platelets are similar to those of a typical 1000 to 1500 mL autologous BM transplant,24,25 despite the infusion of approximately 1 log fewer CD34+ cells per kilogram. In addition, the days of febrile neutropenia appeared to be fewer than recent series of both autologous BM or PBPC transplant.24,25 This finding, initially noted in the phase I trial of ex vivo expansion using perfusion bioreactors17 may have been due to the small numbers of circulating neutrophils seen during the first days after transplant, resulting from the infusion of large numbers of committed myeloid progenitor cells.

As has recently been noted for PBPC transplants, engraftment of both neutrophils and platelets was directly correlated to CD34 cell dose per kilogram transplanted.25,27 Unlike PBPC transplants, in which the minimum dose of CD34 positive cells leading to predictable platelet engraftment in patients with breast cancer by day 28 is 2 to 5 × 106/kg,27 the preliminary data in this trial indicated that only 2 × 105CD34+ cells per kilogram of expanded stem cells was needed to produce optimal platelet engraftment. The engraftment times seen here are at odds with the PBPC CD34+ cell doses in the same range as indicated from several sources,28-30 and several hypotheses may explain our patients' rapid engraftment times. First, STAMP V may not be sufficiently ablative to lead to profound aplasia for periods of longer than 28 days. As indicated above, data from several sources would indicate otherwise. Second, expansion in the perfusion bioreactors led to maintenance of the primitive stem cell pool as measured by the LTCIC and CD34+/Lin− populations, which suggests that the same cell doses infused immediately after collection would produce the same results. We believe that this is unlikely because of a lack of correlation of engraftment to preexpansion CD34+/Lin− cells, and the fact that this is a significantly smaller cell dose of unmanipulated BM cells than needed to reliably reconstitute animals,31,32 and again, we infused fewer CD34+ stem cells than needed to reliably reconstitute hematopoiesis in PBPC clinical trials that have tested the CD34+ doses in the range administered here.28-30 In fact, these data indicate that when less than 1.0 × 106 CD34/kg are infused as part of a PBPC transplant conditioned with non–total body irradiation (TBI) or busulfan-based regimens, including STAMP V chemotherapy, not only are median engraftment times prolonged but as many as 40% of patients do not achieve platelet engraftment by day 60 post transplant. Finally, it may be possible that more primitive stem cells, or possibly “facilitating cells,” including stromal cells33,34 that are infused with the expanded BM cells, are promoting the engraftment of a lower stem cell dose. Unique to these transplants is the infusion of expanded stromal progenitor cells as measured by the CFU-F assay,35 which increase during the 12-day culture period approximately 40-fold, which when infused with hematopoietic stem cells have been demonstrated to be important in facilitating engraftment in a murine model.36 Stromal cell damage exists before transplant,37-39 and recent data indicates that it is damaged as a result of high-dose therapy,40,41 perhaps because of a reduction of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on bone marrow stromal cells after chemotherapy exposure.38 Stromal cell contact appears critical for primitive hematopoietic cell expansion ex vivo,33,34 and these primitive cells maintain their surface expression of cell adhesion molecules unlike cells expanded in stromal-free cultures.42 Thus, it is possible that by infusion of large numbers of stromal progenitor cells with a transplant of hematopoietic stem cells that the same phenomena may be occurring in vivo. In fact, initial clinical trials of mesenchymal cell transplantation either alone or with a typical PBPC transplant are underway.43,44 Expanded mesenchymal cells were infused into 14 patients with advanced breast cancer along with PBPC appeared to shorten engraftment times of neutrophils (greater than 500/μL) and platelets (greater than 20 000) to 8 days each.44

Early hematopoietic engraftment of patients infused with cells grown from stromal cell–based cultures is in contrast to the alternative of transplanting expanded PBPC,45-48 which requires stem cell mobilization, aphereses, and using current technologies, such as CD34 selection before expansion. In addition, the massive expansion of terminally differentiated myeloid cells requires a manual medium exchange during expansion. There appears to be a loss of primitive stem cells, and to date, PBPC expanded in bags have not been successfully used to rescue patients after ablative therapy when they are used alone as the transplant source,45,46 although several have demonstrated a shortening of neutropenia when expanded CD34+ cells are infused along with standard PBPC transplants.45,47 48 Although the technology used here has a lesser degree of total cell expansion, there appears to be a maintenance, or in some cases an expansion of primitive stem cells. In addition, with constant medium exchange in the closed bioreactor system used here, the risks of infectious contamination from a medium exchange procedure during PBPC expansion is minimized.

The expansion of primitive stem cells, as measured by CD34 and LTCIC assays, were less than that seen in preclinical experiments using stromal-based systems. There are several reasons for this: First, initial experiments used BM from normal donors; second, the cytokines used in the earlier studies were GM-CSF, IL-3, Epo, and SCF; and finally some of the previous work on the LTCIC assays used the less accurate secondary colony-forming cell method, whereas the current study used the limiting dilution method.49 As engraftment times were optimal in the current study when CD34+/Lin− cells expanded or in those patients receiving a total CD34+/Lin−dose of greater than 5 × 105/kg, efforts to improve CD34 expansion may yield faster engraftment times. Options tested to date in vitro include adding a thrombopoietic growth factor, which increased the expansion of CD34+/Lin−cells by up to 200%,50 and higher BMSC doses collected after a short course of G-CSF appear promising.51Alternatively, preliminary results using the combination of ex vivo expanded cells and mobilized stem cells from a single apheresis may yield faster engraftment times.52

As a significant number of patients with breast cancer have clonogenic tumor cells found in their marrow or PBPC transplants,3,5 a smaller starting inoculum and passive purging would reduce the risk of tumor cell infusion during transplantation. Although definite conclusions about passive purging cannot be made based on these data, of the 7 samples grossly contaminated with breast cancer recently expanded by Lundell et al,18 4 had no detectable cells in their postexpansion assays, and the other 3 had cell decreases of 40 to 2, 44 to 2, and 2128 to 4 cells per 5 × 106 cells analyzed. Considering a smaller starting inoculum and the passive purging, a 2 to 4 log tumor cell reduction for an expanded BMSC transplant versus a typical unexpanded autologous BM transplant would be expected.

On the basis of our findings, the morbidity associated with BM or PBPC harvesting could be reduced to a simple clinic harvest procedure of little more than an ounce of bone marrow. Such has been accomplished in a preliminary study that is exploring the combination of a single apheresis with ex vivo–expanded BMSC from marrow aliquots obtained in the clinic using local anesthesia and conscious sedation.52This expansion system may also be useful for situations in which there is only a small starting aliquot of stem cells available for transplantation, such as cord blood. In vitro data using this ex vivo expansion system indicates that a significant expansion of stem cells occurs and that sufficient cells may be generated to make this form of transplant available to adults.53 In addition, this technology may be useful in those who mobilize stem cells poorly with current methodologies. Ongoing data, recently reported, suggests that stem cell growth in perfusion bioreactors is independent of stem cell mobilization, with expected expansions seen in patients who are poor mobilizers.54

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the work of Carol Cutrone, Pamela Schumaker, and Christine Kerger at Loyola for their assistance in patient care and data management, Susan Burhop at Aastrom Biosciences for coordinating cell expansions and Hillard Lazarus, MD, for his thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Reprints:Patrick Stiff, Department of Medicine, Cardinal Bernardin Cancer Center, 2160 S First Ave, Maywood, IL 60153.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal