Chemokines are a family of related proteins that regulate leukocyte infiltration into inflamed tissue and play important roles in disease processes. Among the biologic activities of chemokines is inhibition of proliferation of normal hematopoietic progenitors. However, chemokines that inhibit normal progenitors rarely inhibit proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors from patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). We and others recently cloned a subfamily of CC chemokines that share similar amino-terminal peptide sequences and a remarkable ability to chemoattract T cells. These chemokines, Exodus-1/LARC/MIP-3, Exodus-2/SLC/6Ckine/TCA4, and Exodus-3/CKβ11/MIP-3β, were found to inhibit proliferation of normal human marrow progenitors. The study described here found that these chemokines also inhibited the proliferation of progenitors in every sample of marrow from patients with CML that was tested. This demonstration of consistent inhibition of CML progenitor proliferation makes the 3 Exodus chemokines unique among chemokines.

Chemokines are a family of structurally related proteins that are the major mediators of all leukocyte migration.1-4 The chemokine family is subdivided into 2 major groups on the basis of how the first 2 conserved cysteines are arranged. If the first 2 cysteines are separated by a single amino acid, the chemokines are considered to be in the CXC family (alternatively called α). If the first 2 cysteines are immediately adjacent to each other, the chemokines are classified in the CC family (alternatively called β).

Many studies have found that chemokine receptors are important in human disease.1-4 For example, HIV coreceptors (with CD4) were identified as chemokine receptors.5-7 Because of the ability of chemokines to stimulate leukocyte infiltration, they play crucial roles in many diseases in which there is inflammatory tissue destruction, such as adult respiratory distress syndrome, myocardial infarction, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis.8-11CXC chemokines that bind to and activate the chemokine receptor CXCR2 can stimulate angiogenesis, whereas CXC chemokines that bind to CXCR3 inhibit angiogenesis.1-4

We and others have shown that many but not all chemokines from both the CC and CXC family can negatively regulate normal hematopoietic progenitor proliferation.12-18 This inhibition occurs with both human and murine normal marrow progenitors and both in vitro and in vivo. However, we and other investigators have found that this inhibition of progenitor proliferation does not always extend to chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).13 16-18

In this study, we demonstrated that progenitor proliferation in marrow from patients with CML can be significantly and consistently inhibited by a subfamily of CC chemokines that we and others have isolated and that suppress proliferation of normal progenitors.13 This subfamily of CC chemokines are termed Exodus-1/LARC/MIP-3α,14 Exodus-2/SLC/6Ckine/TCA4,15and Exodus-3/ELC/CKβ11/MIP-3β (see Yoshie et al19and Zlotnik et al20 for a review of all 3).

Study design

Patient samples

Institutional review board-approved informed consent was obtained from patients with CML. All patients were in the chronic phase, and none were taking interferon-α (IFN-α). Marrow was aspirated with the patient under local anesthesia and was placed in heparin-coated tubes. All patients had cytogenetic analysis to confirm the diagnosis of CML. In all patients, 100% of metaphases analyzed were positive for t(9;22).

Hematopoietic progenitor assays

Hematopoietic colony-formation assays were performed essentially as previously described.13-15 Low-density mononuclear cells were obtained from heparinized patient marrow by means of Ficoll gradient centrifugation. Low-density human marrow mononuclear cells at a concentration of 5 × 104/mL were plated in 1% methylcellulose in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 30% fetal-calf serum, pure recombinant human erythropoietin (1 U/mL), pure recombinant IL-3 (100 U/mL), and pure recombinant Steel factor (50 ng/mL) for analysis of colony-forming units granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM), colony-forming units granulocyte-erythrocyte-macrophage-megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM), and burst-forming units erythrocyte (BFU-E). Purified recombinant Exodus chemokine proteins (R&D, Minneapolis, MN) were compared with purified recombinant macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), another CC chemokine known to inhibit normal marrow progenitor proliferation but which has shown little activity against CML progenitor proliferation. The concentration chosen after extensive preliminary studies was 100 ng/mL.13-18 This concentration elicits maximal inhibition of normal progenitor-cell proliferation. The percentage of progenitors in S phase at the time of the chemokine treatment was analyzed by tritiated thymidine kill assays as previously described.13-18 Tritiated thymidine is preferentially taken up by cells in S phase and is cytotoxic to those cells because of its radioactivity. Chemokine inhibitory activity is only effective against progenitors in S phase of the cell cycle.12 17

Results and discussion

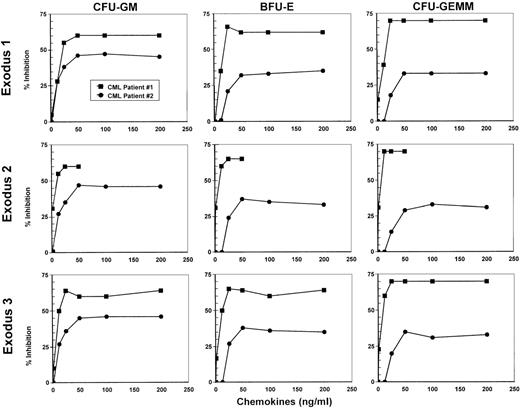

Marrow from 2 patients with CML in the chronic phase who had not received treatment with IFNα was tested for inhibition of hematopoietic progenitor proliferation by using various concentrations of Exodus-1, Exodus-2, and Exodus-3 to establish a dose-response curve (Figure 1). MIP-1α at concentrations ranging from 1.25 ng/mL to 500 ng/mL did not have any inhibitory effect on the proliferation of progenitors in the samples from these patients. However, all 3 Exodus chemokines produced a dose-dependent inhibition of CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-GEMM progenitor proliferation in both patient samples, beginning at a concentration of 12.5 ng/mL (Figure 1). At 1.25 ng/mL, there was little inhibition. The dose-response curve was similar for all the Exodus chemokines. When both CML patient samples were taken into account, this inhibitory response leveled off at between 50 ng/mL and 100 ng/mL. Therefore, for more extensive studies, we chose 100 ng/mL as the concentration of Exodus-1, Exodus-2, and Exodus-3 chemokine to obtain maximal response in all progenitor assays.

Dose-response curves of the inhibition of proliferation of CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-GEMM by Exodus-1, Exodus-2, and Exodus-3.

Progenitor assays of marrow from 2 newly diagnosed, untreated patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) were performed with varying concentrations of the Exodus chemokines. MIP-1α served as a negative control and did not inhibit CFU-GM proliferation to any appreciable extent, even at concentrations of up to 500 ng/mL. Data are presented as the average of the percentage of proliferative inhibition from triplicate cultures compared with control average colony formation without chemokine treatment. Mean (± SD) control colonies were 22 ± 3 for CFU-GM, 126 ± 14 for BFU-E, and 13 ± 3 for CFU-GEMM for CML patient 1 and 195 ± 10 for CFU-GM, 168 ± 10 for BFU-E, and 49 ± 5 for CFU-GEMM for CML patient 2.

Dose-response curves of the inhibition of proliferation of CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-GEMM by Exodus-1, Exodus-2, and Exodus-3.

Progenitor assays of marrow from 2 newly diagnosed, untreated patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) were performed with varying concentrations of the Exodus chemokines. MIP-1α served as a negative control and did not inhibit CFU-GM proliferation to any appreciable extent, even at concentrations of up to 500 ng/mL. Data are presented as the average of the percentage of proliferative inhibition from triplicate cultures compared with control average colony formation without chemokine treatment. Mean (± SD) control colonies were 22 ± 3 for CFU-GM, 126 ± 14 for BFU-E, and 13 ± 3 for CFU-GEMM for CML patient 1 and 195 ± 10 for CFU-GM, 168 ± 10 for BFU-E, and 49 ± 5 for CFU-GEMM for CML patient 2.

Marrow was obtained from 13 additional patients with CML in the chronic phase who were not taking IFN-α. Tritiated thymidine kill assays were used to test the marrow samples for the percentage of progenitors in S phase. In these samples, an average of 56% of CFU-GM, 49% of BFU-E, and 53% of CFU-GEMM progenitor cells were in S phase (Figure2).

Influence of Exodus subfamily of CC chemokines on colony formation of progenitors in marrow from patients with CML.

Data are presented as the percentage of inhibition compared with control colony formation (without chemokine treatment) for each patient. Mean (± SD) control colonies were 69 ± 83 for CFU-GM, 85 ± 55 for BFU-E, and 35 ± 36 for CFU-GEMM. For the CML patient samples, data are presented as average values, with SD bars. If no SD bars are shown, the SD was too small to be included on the figure. For Exodus-1, n = 13; for Exodus-2, n = 4; for Exodus-3, n = 3; and for MIP-1α, n = 11. Two CML patient samples in which MIP-1α inhibited the progenitors are not on the figure but are discussed in the text.

Influence of Exodus subfamily of CC chemokines on colony formation of progenitors in marrow from patients with CML.

Data are presented as the percentage of inhibition compared with control colony formation (without chemokine treatment) for each patient. Mean (± SD) control colonies were 69 ± 83 for CFU-GM, 85 ± 55 for BFU-E, and 35 ± 36 for CFU-GEMM. For the CML patient samples, data are presented as average values, with SD bars. If no SD bars are shown, the SD was too small to be included on the figure. For Exodus-1, n = 13; for Exodus-2, n = 4; for Exodus-3, n = 3; and for MIP-1α, n = 11. Two CML patient samples in which MIP-1α inhibited the progenitors are not on the figure but are discussed in the text.

Next, the effect of MIP-1α on CML progenitor-cell proliferation was tested. MIP-1α inhibits normal marrow progenitor-cell proliferation but most often does not act on CML progenitors.16-18 As expected, MIP-1α did not significantly inhibit progenitor proliferation in 11 of the 13 CML marrow samples (Figure 2). However, in 2 samples, MIP-1α did inhibit progenitor proliferation: the average percentage of inhibition in these samples compared with untreated controls was 43% for CFU-GM, 37% for BFU-E, and 50% for CFU-GEMM. In contrast, in all 13 CML samples, progenitor proliferation was significantly inhibited by Exodus-1 (P < .01). CFU-GM were inhibited by an average of 53%, BFU-E by an average of 47%, and CFU-GEMM by an average of 52% (Figure 2).

Because Exodus-2 and Exodus-3 were isolated and characterized some time after Exodus-1, fewer CML samples were analyzed with those chemokines. In the 4 CML marrow samples tested, Exodus-2 significantly inhibited (P < .01) CFU-GM proliferation by an average of 61%, BFU-E by an average of 49%, and CFU-GEMM by an average of 50%. In the 3 CML samples tested, Exodus-3 significantly inhibited (P < .01) CFU-GM proliferation by an average of 57%, BFU-E by an average of 50%, and CFU-GEMM by an average of 48%.

Thus, progenitor proliferation in all the samples of marrow from patients with CML we tested was significantly inhibited by all 3 Exodus subfamily chemokines. There were no significant differences between the 3 chemokines in their ability to maximally inhibit progenitor proliferation. All 3 Exodus chemokines were markedly more effective than MIP-1α at inhibiting CML progenitor proliferation. Exodus-1 uses CCR6 as its receptor and Exodus-2 and Exodus-3 use CCR7. The data presented here offer the possibility that activation of CCR6 and CCR7 may inhibit proliferative signals in hematopoietic progenitors in patients with CML.21Much of the morbidity of CML in the chronic phase is due to the pancytosis that results from a proliferative advantage that CML progenitors have over normal marrow progenitors. Use of the Exodus chemokines may be an effective approach to controlling blood-cell production in CML. The possibility that the Exodus chemokines could produce cytogenetic remissions awaits a clinical trial. It would be especially interesting to see whether the Exodus chemokines can produce responses in chronic-phase patients with CML in whom treatment with IFN-α has failed.

Supported by US Public Health Service grants RO1 HL56416 and DK53674 to H.E.B. and RO1 HL48914 to R.H., who is also supported by a Leukemia Society of America Scholar Award and a Translational Research Award.

Reprints:Robert Hromas, Walther Oncology Center, Indiana University Medical Center, R4-202, 1044 W Walnut St, Indianapolis, IN 46202; e-mail: rhromas@iupui.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal