BCR-ABL is a chimeric oncogene generated by translocation of sequences from the chromosomal counterpart (c-ABLgene) on chromosome 9 into the BCR gene on chromosome 22. Alternative chimeric proteins, BCR-ABLp190 and BCR-ABLp210, are produced that are characteristic of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph1-ALL). In CML, the transformation occurs at the level of pluripotent stem cells. However, Ph1-ALL is thought to affect progenitor cells with lymphoid differentiation. Here we demonstrate that the cell capable of initiating human Ph1-ALL in non-obese diabetic mice with severe combined immunodeficiency disease (NOD/SCID), termed SCID leukemia–initiating cell (SL-IC), possesses the differentiative and proliferative capacities and the potential for self-renewal expected of a leukemic stem cell. The SL-ICs from all Ph1-ALL analyzed, regardless of the heterogeneity in maturation characteristics of the leukemic blasts, were exclusively CD34+CD38−, which is similar to the cell-surface phenotype of normal SCID-repopulating cells. This indicates that normal primitive cells, rather than committed progenitor cells, are the target for leukemic transformation in Ph1-ALL.

Acute leukemia derives from the clonal expansion of hematopoietic precursors that have lost their capacity to proceed to terminal differentiation. Leukemogenesis would therefore require the accumulation of the minimum number of genetic events that result in accelerated cell growth and differentiation block. A large number of genetic alterations, including specific chromosome translocations, have been identified and causally linked to leukemogenesis, but the molecular basis of the composite leukemia phenotype remains largely unknown.1

A well-characterized example in the hematopoietic system involves the rearrangements of the BCR and ABL genes in Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph1+) chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and acute lymphocytic leukemia (Ph1-ALL).2-11 Depending on the precise breakpoint within the BCR gene, fusion proteins of 210 d (p210) or 190 d (p190) are produced.2-11 The p210 and p190BCR-ABL oncogenes contain identical ABL-derived sequences, respectively, but differ in the number of BCR-encoded amino acid residues. The resulting oncoproteins, BCR-ABLp210 and BCR-ABLp190, are required and sufficient for the malignant transformation of hematopoietic cells.12

In CML, the transformation occurs at the level of pluripotent stem cells.13 However, in most cases of Ph1-ALL, which have a differentiated phenotype, the leukemogenic genetic defect is believed to affect progenitor cells with lymphoid differentiation.14 These cases of Ph1-ALL represent 30% of adult ALL cases, predominantly of B lineage, making it the most frequently identified translocation in this group.15 Ph1-ALL is characterized by the accumulation of large numbers of abnormal cells that fail to differentiate into functional B lymphocytes.14,15 The leukemic blasts have limited proliferative capacity, which suggests that a small subpopulation of leukemic stem cells possess extensive proliferative capacity and that the potential for self-renewal must maintain the leukemia.15 16 Characterization of the leukemic stem cells is fundamental in order to gain insight into the composition of the leukemic clone and into the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie leukemogenesis.

Because of the absence of a direct link between a cell carrying the cytogenetic abnormality (BCR-ABLp190) and a test of whether this cell has the capacity to maintain the disease in vivo, 2 different hypotheses try to explain the link between theBCR-ABLp190 oncogene and the Ph1-ALL. One hypothesis suggests that many cell types in the stem/progenitor hierarchy are susceptible to transformation.14,17 The leukemogenic event would alter the normal development program, thereby resulting in the expansion of abnormal cells that are blocked at a particular stage of differentiation. The degree of commitment of the target cell influences the characteristics of the resulting leukemic blast cells. The second hypothesis suggests that mutations responsible for transformation and progression occur in primitive cells only.16 According to this theory, the phenotype results from the ability of these primitive leukemic stem cells to differentiate, depending on the influence of the specific leukemogenic event. Resolution of this controversy is critical in order to gain insight into the mechanism of oncogene action in leukemic transformation and the design of new therapeutic strategies.

In this study we report that the cell capable of initiating human Ph1-ALL in non-obese diabetic mice with severe combined immunodeficiency disease (NOD/SCID), termed the SCID leukemia–initiating cell (SL-IC), possesses differentiative and proliferative capacities and has the potential for self-renewal expected of a leukemic stem cell. The phenotype of SL-ICs was similar to that of normal stem cells and was the same in every patient, regardless of the lineage markers expressed by the leukemic blasts. This indicates that normal primitive cells, rather than committed progenitor cells, are the target for leukemic transformation in Ph1-ALL.

Materials and methods

Human cells

Leukemic peripheral blood specimens from patients with Ph1-ALL were obtained after informed consent, and classification was made according to French-American-British (FAB) and immunological criteria.37 The presence of theBCR-ABLp190 oncogene was confirmed in all cases by cytogenetic and molecular biology techniques. The BCR-ABLp210 product could not be detected in any case.

Animals and transplantation of Ph1-ALL cells into NOD/SCID mice

NOD/SCID mice (breeding pairs; Dr F. Serrano, Centro Nacional Biotecnologı́a, Madrid, Spain) were bred and maintained in the animal facilities of the University of Salamanca (Salamanca, Spain). All animals were handled under sterile conditions and maintained under microisolators. The mice to be transplanted were irradiated at 6-8 weeks of age with 350 to 400 cGy of total body irradiation from a cesium 137 (137Cs) source, and then within 24 hours the mice were given a single intravenous injection of low-density human cells. All mice were also given intraperitoneal injections of various human recombinant growth factors as indicated, every other day or 3 times per week. Each of the following doses are given as units per mouse/injection: 15 units human erythropoietin (Ortho Biotech, Barcelona, Spain); 7 μg PIXY321 (Immunex, Seattle, WA); 6 μg each of interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-7, and granulocyte-macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Sandoz International, Madrid, Spain); and 10 μg Steel factor (SF) (Immunex). We obtained the best number of human CD34+ cells in these mice with this specific combination of growth factors.

Flow cytometric detection of human cells in murine tissues and sorting

Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs and tibias of each mouse to be assessed using a syringe and a 26-gauge needle at indicated time points (4-8 weeks). Single-cell suspensions were then prepared by gentle aspiration. To prepare cells for flow cytometry, contaminated red blood cells were lysed with 8.3% ammonium chloride, and the remaining cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 5% human serum to block fragment (Fc) receptors.

Cells from a normal NOD/SCID mouse were also stained with each of the monoclonal (mAbs) used for detecting positively-stained human cells. Only levels of fluorescence that excluded more than 99.9% of all of these negative controls were considered specific. After staining, all cells were washed once in PBS with 2% FCS and then once again in PBS with 2% FCS containing 2 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) to allow dead cells to be excluded from both analyses and sorting procedures. We used the following mAbs (Becton Dickinson, Madrid, Spain): anti-CD45, anti-CD34, anti-CD38, anti-CD19, anti-CD10, anti-CD13, anti-CD33, anti-CD7, and anti-CD3. The mAbs were conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), or peridinin chlorophyl protein (PerCp).

Cells were analyzed and sorted on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACStar Plus, Becton Dickinson) that was equipped with 5 W argon and 30 MW helium neon lasers. Gate was established with specific fluorescence of FITC and PE, excited at 488 nm (0.4 W) and 633 nm (30 μW), respectively, and known forward- and orthogonal-lightscattering properties of human cells. Data acquisition and analysis were performed (LYSIS II software, Becton Dickinson). For each analysis, a total of 5000 viable (PI−) cells were assessed; the values were used to calculate a number of human cells of a given phenotype only after 5 positive events were recorded.

In vitro hematopoietic cell culture assays

To support the formation of myeloid colonies, progenitors were cultured in an alpha–Modified Eagle Medium–based (αMEM-based) methylcellulose media (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) that was supplemented with 30% FBS, 1% bovine serum albumin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol. Cytokines such as human erythropoietin were added at the start of the culture. To examine lymphoid colony formation, we used Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium–based (IMDM-based) methylcellulose (StemCell Technologies) containing human IL-7 (10 ng/mL). All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber under 5% carbon dioxide. The different categories of human colonies known to be generated under either of these conditions were scored in situ after 2-3 weeks of incubation at 37°C using well-established criteria. Duplicate plates were scored for each mouse. Leukemic blast colonies (20-100 cells) were scored at 7-8 days. The leukemic origin of the colonies was confirmed by individually plucking each colony and examining the immunophenotype. Only leukemic cells were detected from normal clonogenic progenitors. Normal human progenitors were not detected, even when cultures were left for an additional week. All leukemic colonies contained the BCR-ABLp190 chromosome translocation.

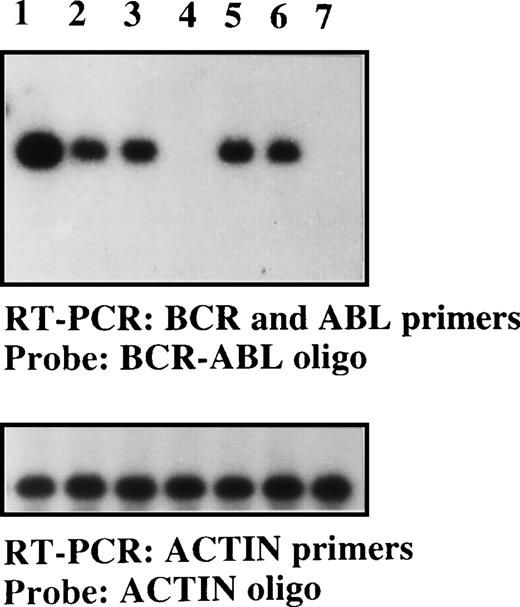

Detection of the BCR-ABLp190fusion gene product

The BCR-ABLp190 product was detected by polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using specific primers for both human BCR and ABL genes in engrafted NOD/SCID and control NOD/SCID mice and in vitro colonies. The specific BCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product was identified by hybridization with a specifc oligo spanning the gene fusion. The complementary DNA (cDNA) integrity was measured by hybridization of the RT-PCR product using actin specific primers with an internal actin human primer.

DNA extraction and analysis

High molecular weight DNA was isolated from the bone marrow of transplanted mice, EcoRI digests of genomic DNA (1 μg) were loaded into each lane, and the blots were hybridized with a human chromosome 17-specific α-satellite probe (p17H8), as previously described.19 The proportion of human cells in each sample was then inferred from the intensity of the characteristic 2.7 kilobase (kb) band obtained relative to those obtained on the same blot from a series of artificial mixtures of human and mouse DNA (ranging from 0.1%-50% human DNA).

Results

Development of the NOD/SCID leukemia model for Ph1-ALL

Previous reports20-22 show that NOD/SCID mice are superior to other mouse strains for the engraftment of limiting cell doses or purified populations of normal human cells. The ability of NOD/SCID mice to become engrafted after the transplantation of lower cell doses and to regenerate higher numbers of very primitive human cells may be due, at least in part, to a reduced ability of NOD/SCID mice to eliminate foreign (xenogenic) cells, particularly when low numbers of cells are injected. Therefore, NOD/SCID mice are recipients of routine experimental studies of human hematopoiesis in an in vivo setting. To determine if NOD/SCID mice were optimal recipients for the engraftment of human Ph1-ALL cells, different cell doses were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice using standard procedures.23-25 The proportion of human cell engraftment in each sample was analyzed by Southern blot 4 to 6 weeks after transplant and then deduced from the intensity of the characteristic 2.7 kb band19 obtained on the same blot from a series of artificial mixtures of human and mouse DNA (Table1). All samples from all patients were engrafted in the NOD/SCID mice to high levels (5%-100%). No normal human progenitors (defined by the absence of BCR-ABLp190) or cells with normal morphology were detected in the bone marrow of these mice (data not shown). This mouse model should therefore serve as a useful starting point for the further characterization of such Ph1-ALL cells in order to demonstrate the in vivo proliferative and developmental potential of transformed Ph1-ALL progenitors at various developmental stages.

Phenotypic characteristics of B-acute Ph1-ALL

| Patient No. . | FAB Subtype . | Age/ Sex . | Level of Engraftment of NOD/SCID Mice With 10 × 106 MNCs . | % CD34+ in MNCs . | % CD34++CD38− in MNCs . | Estimated Frequency of SL-ICs/106 MNCs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L2 | 16/M | 35 ± 6 | 94 | 18 | 41 |

| 2 | L2 | 34/F | 70 ± 8 | 90 | 24 | 12 |

| 3 | L1 | 42/M | 61 ± 6 | 78 | 19 | 3 |

| 4 | L2 | 24/M | 43 ± 7 | 85 | 20 | 2 |

| 5 | L1 | 37/F | 71 ± 9 | 93 | 5 | 0.2 |

| 6 | L2 | 29/M | 27 ± 8 | 94 | 21 | 9 |

| 7 | L2 | 33/M | 26 ± 6 | 84 | 26 | 19 |

| Patient No. . | FAB Subtype . | Age/ Sex . | Level of Engraftment of NOD/SCID Mice With 10 × 106 MNCs . | % CD34+ in MNCs . | % CD34++CD38− in MNCs . | Estimated Frequency of SL-ICs/106 MNCs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L2 | 16/M | 35 ± 6 | 94 | 18 | 41 |

| 2 | L2 | 34/F | 70 ± 8 | 90 | 24 | 12 |

| 3 | L1 | 42/M | 61 ± 6 | 78 | 19 | 3 |

| 4 | L2 | 24/M | 43 ± 7 | 85 | 20 | 2 |

| 5 | L1 | 37/F | 71 ± 9 | 93 | 5 | 0.2 |

| 6 | L2 | 29/M | 27 ± 8 | 94 | 21 | 9 |

| 7 | L2 | 33/M | 26 ± 6 | 84 | 26 | 19 |

FAB criteria18 and NOD/SCID mice were used.

Patient Nos. 1, 2, 4, and 7 showed expression of myeloid antigens. The MNCs of all patients were transplanted at the dose indicated into 56 NOD/SCID mice using conditions previously described.

The level of human cell engraftment of the mice transplanted was determined by Southern blot analysis, using a human-specific α-satellite probe, and compared with the intensity of the bands of the human/mouse mixtures.

The level of engraftment of Ph1-ALL samples in NOD/SCID mice indicated that it might be possible to develop a quantitative assay for SL-ICs, the cells capable of initiating human Ph1-ALL in NOD/SCID mice. Serial dilutions of unseparated mononuclear cells (MNCs) (range 5 × 104 to 5 × 107) from 7 Ph1-ALL patients were injected into at least 4 NOD/SCID mice per cell dose. A minimum estimate of the SL-IC frequency was determined from the lowest cell dose that resulted in human cell engraftment in at least some of the group of at least 4 mice. The data were analyzed by the application of Poisson statistics to the single-hit model,24,26 and the frequency of SL-ICs was calculated by using the maximum likelihood estimator.27 As summarized in Table 1, the estimated frequency of SL-ICs in the PBLs of the 7 patients varied widely, from 0.2 to 41 SL-ICs per 106 MNCs. The frequency of SL-ICs in the PBLs was independent of the number of cells injected. Then we analyzed whether the frequency of SL-ICs was related to some of the characteristics of Ph1-ALL samples. No correlation was observed between the frequency of SL-ICs and the age, sex, FAB subtype, or percentage of CD34+ cells in the blast population.

Nature of the SL-ICs in Ph1-ALL

In order to characterize the nature of the cell type that initiated the leukemic clone in transplanted NOD/SCID mice, we analyzed the cell-surface phenotype of SL-ICs from the different Ph1-ALL patients. We focused on surface markers such as CD34 and CD38 antigens because it has been shown that normal stem cells20-25 and AML-leukemic stem cells repopulating immunodeficient mice were exclusively CD34+ and CD38−.25 28-30 As was expected, there was considerable heterogeneity from patient to patient in the expression of CD34 and CD38 antigens in the Ph1-ALL samples (Table 1). Ph1-ALL samples were first sorted into highly purified CD34+ and CD34− cell fractions that were injected at different cell doses into NOD/SCID mice. A representative experiment from patient No. 2 is shown in Figure1. In this sample, 90% of the original blast population comprised CD34+ cell fractions. SL-ICs were only present in the CD34+ fraction, and as few as 2 × 104 CD34+ cells were able to initiate the proliferation of leukemic cells, whereas 100 times as many CD34− cells did not engraft.

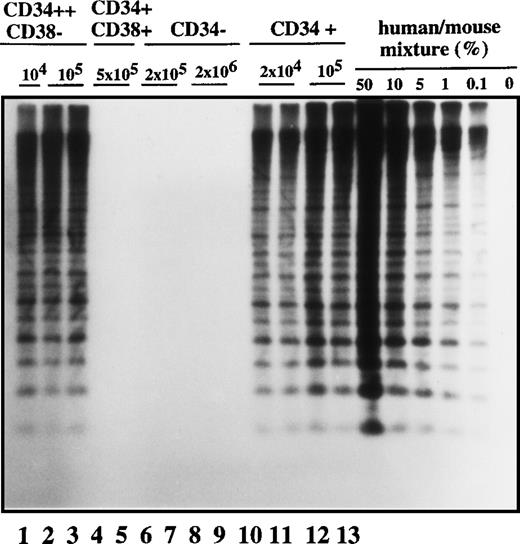

Human cell engraftment with selected Ph1-ALL cells according to CD34 and CD38 expression in the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice.

Mice were implanted with the indicated number of purified cells (CD34+, CD34−, CD34++CD38−, or CD34+CD38+, respectively) from patient No. 2, and 4-6 weeks later, human cell engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis and then inferred from the intensity of the characteristic 2.7 kb band.19 Each mouse was analyzed independently using this strategy. This experiment is representative of 3 independent experiments.

Human cell engraftment with selected Ph1-ALL cells according to CD34 and CD38 expression in the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice.

Mice were implanted with the indicated number of purified cells (CD34+, CD34−, CD34++CD38−, or CD34+CD38+, respectively) from patient No. 2, and 4-6 weeks later, human cell engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis and then inferred from the intensity of the characteristic 2.7 kb band.19 Each mouse was analyzed independently using this strategy. This experiment is representative of 3 independent experiments.

Cells with the CD34 surface antigen were further fractionated on the basis of CD38 expression. The sorting strategy and the purity of each cell population obtained in these sorts are shown in Figure2. Only the CD34++CD38− fraction contained SL-ICs, whereas as many as 5 × 105CD34+CD38+ cells did not engraft (Figure 1). The same results were obtained from the bone marrow of mice injected with CD34+CD38+ purified cells from patient No. 6 (Figure 3). The results of experiments performed for the additional patients are summarized in Table2 and represent the percentage of engraftment of selected Ph1-ALL cells in mouse recipients. In all cases, the SL-ICs were exclusively CD34++CD38−. This was also the case with Ph1-ALL patient No. 5, in whom the CD34++CD38− subpopulation represented only 5% of the total blast population. Thus, in all Ph1-ALL samples studied, the SL-ICs were always found in the CD34++CD38− subfraction.

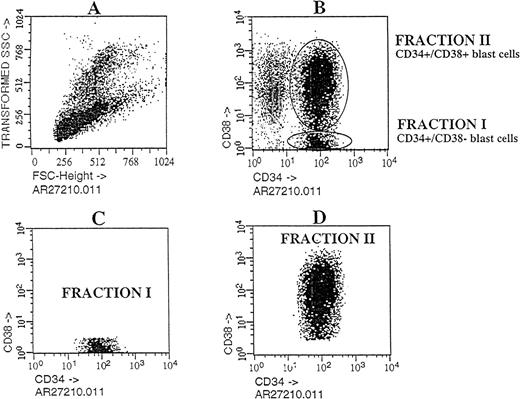

Flow cytometric analysis of Ph1-ALL cells purified according to their distribution of CD34 and CD38 expression.

Cells from PBLs of patient No. 2 were analyzed by flow cytometry. The blast lymphoid gated cell population was then analyzed for CD34 and CD38 expression. Circles containing cells that express CD34++CD38− and CD34+CD38+ cells were chosen as the sorting region. These cells, fractionated into pure CD34++CD38− and CD34+CD38+ subgroups, were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice.

Flow cytometric analysis of Ph1-ALL cells purified according to their distribution of CD34 and CD38 expression.

Cells from PBLs of patient No. 2 were analyzed by flow cytometry. The blast lymphoid gated cell population was then analyzed for CD34 and CD38 expression. Circles containing cells that express CD34++CD38− and CD34+CD38+ cells were chosen as the sorting region. These cells, fractionated into pure CD34++CD38− and CD34+CD38+ subgroups, were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice.

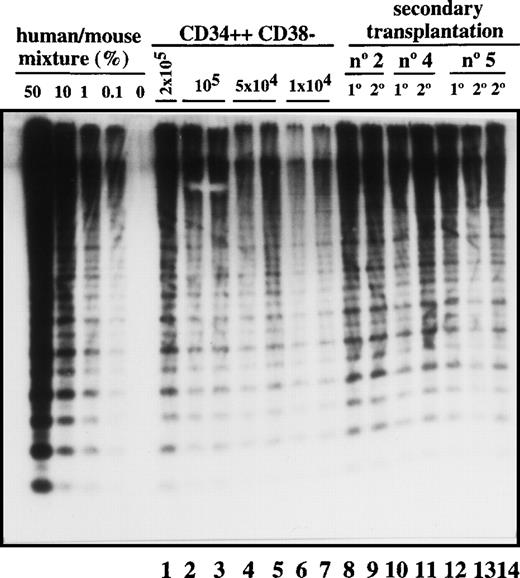

Transplantation of SL-ICs into secondary recipients.

Lanes 1-7: CD34++CD38− leukemic cells from patient No. 6 were injected at the indicated doses into NOD/SCID mice. After 6-8 weeks, these mice were sacrificed, and the percentage of engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis. Lane 8: Pool from the bone marrow of 8 mice injected with 2 × 104 CD34 cells from patient No. 2. Lane 9: Human CD45+ cells present in primary engrafted mice were sorted; 2 × 105 cells were injected into secondary recipients; and after 6 weeks, engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis. Lane 10: Pool from the bone marrow of 8 mice injected with 10 × 106 unsorted cells from patient No. 4. Lane 11: Secondary recipient mouse injected with 2 × 106 CD45+ cells from the previous pool of mice. Lane12: Pool from the bone marrow of 9 mice injected with 2 × 105 CD34+ cells from patient No. 5. Lanes 13 and 14: Secondary recipient mice injected with 2 × 105 and 2 × 106 CD45 cells, respectively, from the pool of mice shown in lane 12.

Transplantation of SL-ICs into secondary recipients.

Lanes 1-7: CD34++CD38− leukemic cells from patient No. 6 were injected at the indicated doses into NOD/SCID mice. After 6-8 weeks, these mice were sacrificed, and the percentage of engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis. Lane 8: Pool from the bone marrow of 8 mice injected with 2 × 104 CD34 cells from patient No. 2. Lane 9: Human CD45+ cells present in primary engrafted mice were sorted; 2 × 105 cells were injected into secondary recipients; and after 6 weeks, engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis. Lane 10: Pool from the bone marrow of 8 mice injected with 10 × 106 unsorted cells from patient No. 4. Lane 11: Secondary recipient mouse injected with 2 × 106 CD45+ cells from the previous pool of mice. Lane12: Pool from the bone marrow of 9 mice injected with 2 × 105 CD34+ cells from patient No. 5. Lanes 13 and 14: Secondary recipient mice injected with 2 × 105 and 2 × 106 CD45 cells, respectively, from the pool of mice shown in lane 12.

Engraftment of selected Ph1-ALL cells into NOD/SCID mice

| Patient No. . | CD34− . | CD34+ . | CD34+ CD38+ . | CD34++CD38− . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <1 | 2 ± 0.5 | <1 | 6 ± 0.4 |

| 2 | <1 | 8 ± 0.7 | <1 | 9 ± 0.8 |

| 3 | <1 | 12 ± 1 | <1 | 10.5 ± 0.9 |

| 4 | <1 | 7.5 ± 0.4 | — | — |

| 5 | <1 | 9 ± 0.9 | <1 | 8.5 ± 0.7 |

| 6 | <1 | 6 ± 0.5 | <1 | 6 ± 0.4 |

| 7 | <1 | 11 ± 1.1 | <1 | 9.5 ± 0.8 |

| Patient No. . | CD34− . | CD34+ . | CD34+ CD38+ . | CD34++CD38− . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <1 | 2 ± 0.5 | <1 | 6 ± 0.4 |

| 2 | <1 | 8 ± 0.7 | <1 | 9 ± 0.8 |

| 3 | <1 | 12 ± 1 | <1 | 10.5 ± 0.9 |

| 4 | <1 | 7.5 ± 0.4 | — | — |

| 5 | <1 | 9 ± 0.9 | <1 | 8.5 ± 0.7 |

| 6 | <1 | 6 ± 0.5 | <1 | 6 ± 0.4 |

| 7 | <1 | 11 ± 1.1 | <1 | 9.5 ± 0.8 |

Groups of 8-10 mice were transplanted with 2 × 105purified CD34+, CD34−, or CD34+CD38+ cells and 0.2 × 105CD34++CD38− cells. Human cell engraftment was estimated by Southern blot analysis 4-6 weeks later, as previously described.

In vivo differentiative capacity of SL-ICs in Ph1-ALL

To determine the proliferative and differentiative capacity of purified CD34++CD38− SL-ICs in NOD/SCID mice, flow cytometric analyses were performed on the bone marrow of the engrafted mice and compared with the analysis of the original donor cells. We ruled out the presence of normal cells by 2 lines of evidence: First, normal human colonies were not detected in mice with human grafts (all the colonies expressed theBCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product), and second, flow cytometric analysis demonstrated abnormal leukemic cell-surface phenotype exclusively.

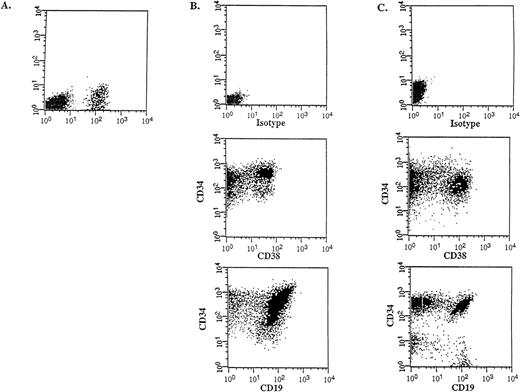

Flow cytometric analysis was performed on the donor samples and on the bone marrow of engrafted mice to compare the immunophenotype and to determine the differentiative capacity of the CD34++CD38− SL-ICs. A representative experiment is shown in Figure 4 (patient No. 5). The injection of 105CD34++CD38− cells into NOD/SCID mice resulted in 12% CD45+ human cells (Figure 4A), which indicated a large expansion from the engrafted SL-ICs. Most of these cells expressed CD34, CD38 and CD19 (Figure 4B), indicating that the injected CD34++CD38− cells were able to acquire lineage markers and/or to differentiate in vivo, resulting in an abnormal leukemic phenotype characteristic of the donor sample (Figure 4C). The absence of myeloid and erythroid markers and the detection of the BCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product in bone marrow–derived human cells (Figure5) further proved that there were no normal progenitors engrafted in these mice. Furthermore, a significant population (15%) of the engrafted human cells retained the CD34++CD38− phenotype, which suggests that these cells could have the capacity to renew themselves.

In vivo differentiative capacity of SL-ICs analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cell surface marker analysis of a representative engrafted NOD/SCID mouse is shown. (A) Six weeks later, bone marrow cells from a NOD/SCID mouse implanted with 105 CD34++CD38−cells from patient No. 5 were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with anti–CD45 mAb and the mouse isotype IgG1 control mAb. Viable cells were sorted according to their CD45 expression. (B) The CD45+ gated cells were stained with anti–CD34-FITC, anti–CD38-PE, and anti–CD19-PE mAbs, respectively. (C) Identical cell surface marker analysis was performed on the original blasts of patient No. 5.

In vivo differentiative capacity of SL-ICs analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cell surface marker analysis of a representative engrafted NOD/SCID mouse is shown. (A) Six weeks later, bone marrow cells from a NOD/SCID mouse implanted with 105 CD34++CD38−cells from patient No. 5 were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with anti–CD45 mAb and the mouse isotype IgG1 control mAb. Viable cells were sorted according to their CD45 expression. (B) The CD45+ gated cells were stained with anti–CD34-FITC, anti–CD38-PE, and anti–CD19-PE mAbs, respectively. (C) Identical cell surface marker analysis was performed on the original blasts of patient No. 5.

Detection of the BCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product in the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice with human Ph1-ALL grafts.

RT-PCR detection of the BCR-ABLp190fusion gene using specific primers for both human BCRand ABL genes in engrafted NOD/SCID mice with 105 cells (lane 1, patient No. 1; lane 2, patient No. 2; lane 3, patient No. 3; lane 5, patient No. 5; and lane 6, patient No. 6) and control NOD/SCID mice (lanes 4 and 7). The specificBCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product was identified by hybridization with a specific oligo spanning the gene fusion. The cDNA integrity was measured by hybridization of the RT-PCR product using actin-specific primers with an internal actin human primer.

Detection of the BCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product in the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice with human Ph1-ALL grafts.

RT-PCR detection of the BCR-ABLp190fusion gene using specific primers for both human BCRand ABL genes in engrafted NOD/SCID mice with 105 cells (lane 1, patient No. 1; lane 2, patient No. 2; lane 3, patient No. 3; lane 5, patient No. 5; and lane 6, patient No. 6) and control NOD/SCID mice (lanes 4 and 7). The specificBCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product was identified by hybridization with a specific oligo spanning the gene fusion. The cDNA integrity was measured by hybridization of the RT-PCR product using actin-specific primers with an internal actin human primer.

Clonogenic Ph1-ALL cells and resulting colonies in methylcellulose cultures

We further characterized the differentiation capacity of the Ph1-ALL population in methylcellulose culture. First, we cultured the cells taken from the engrafted murine marrow under the conditions for myeloid colony formation. In long-term hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) subsets, 80% of the cells can respond to the methylcellulose cultures containing the SF or c-kit ligand, IL-3, IL-6, GM-CSF, and erythropoietin, while only 20%-40% of the cells respond in the short-term HSC subsets.31 However, the Ph1-ALL cells did not form colonies in various cultures for myeloid colonies.

As it has been shown that B-cell precursors in the bone marrow could form pre-B colonies in methylcellulose containing IL-7,31we cultured Ph1-ALL cells in the methylcellulose cultures that incorporate IL-7. The Ph1-ALL cells formed colonies. We studied the expression of theBCR-ABLp190 fusion gene product in 27 colonies by RT-PCR, and all of them presented the specific transcript. These colonies were defined as pre-B colonies on day 10, as all of them presented a characteristic CD19+, CD43+, and immunoglobulin M− (IgM−) phenotype. When we sorted different numbers of the cells into 96-well plates with methylcellulose containing IL-7, the frequency of the cells responding to this culture condition, determined on day 10 by the limit dilution analysis, was also approximately 1 in 5 cells. But when we picked cells from the blastic colonies and replated them in methylcellulose culture containing SF, IL-3, IL-6, GM-CSF, and erythropoietin, we could not detect secondary myeloid colonies in these conditions.

Self-renewal capacity of SL-ICs assessed by serial transplantation

Most leukemic blasts in Ph1-ALL have limited proliferative capacity and therefore must be constantly replenished by primitive cells capable of self-renewal. To determine whether SL-ICs have self-renewal potential, leukemic cells were transplanted serially into secondary recipients. As shown in Figure 3, all 3 samples could be successfully transplanted into secondary recipients with equivalent levels of human cell engraftment. The leukemic cell-surface phenotype was unchanged (data not shown). By the use of the quantitative SL-IC assay, the number of SL-ICs present in the donor sample and the primary NOD/SCID mouse was determined by densitometric analysis. For example, 8 mice were injected with 16 × 106 cells from patient No. 2. Since the frequency of SL-ICs in this sample was 12/106 cells (Table 1), each mouse was implanted with 192 SL-ICs. After 6 weeks, 1.2 × 108 pooled bone marrow cells from the 8 mice averaged 40% human cells as determined by densitometric analysis (Figure 3, lane 8). Taking into account that only 40% of the total bone marrow cells present in the mice were recovered, a total of 1.2 × 108 CD45+cells were present in the bone marrow of these 8 mice. These CD45+ cells were sorted, and recipient secondary mice were injected with 2 × 105cells. Because the mice injected with the 2 × 105cells contained human cells (Figure 3, lane 9), the frequency of SL-ICs must be at least 1 SL-IC per 2 × 105 cells (or 600 per 1.2 × 108), which indicates that a minimum 80-fold expansion of SL-ICs must have occurred in the primary recipient. Similar calculations for the other 2 samples indicated a 40- to 100-fold expansion of SL-ICs. This calculation probably underestimates the SL-IC expansion because it assumes 100% recovery and does not account for efficiency of seeding to the recipient bone marrow.

Discussion

SL-ICs in Ph1-ALL have the properties of stem cells

We have characterized Ph1-ALL stem cells from samples of different patients on the basis of their ability to initiate human Ph1-ALL after transplantation of CD45+ sorted cells into NOD/SCID mice or SL-ICs. SL-ICs possessed 2 key criteria that define stem cells: (1) after transplantation, stem cells were able to proliferate and to differentiate, thereby producing a disease in mice which was identical to that in the donor, and (2) the stem cells were able to renew themselves, thereby enabling the reestablishment of Ph1-ALL in secondary recipient mice. The proliferative potential of SL-ICs is enormous, since millions of CD34++CD38− cells could be generated from NOD/SCID recipients implanted with a single CD34++CD38− SL-IC at limiting dilution. Serial transplantation demonstrates that the SL-ICs are capable of self-renewal for up to 8 weeks, thereby giving rise to a 30- to 100-fold expansion of the SL-IC pool in the primary transplanted NOD/SCID recipient. Future studies will define whether the SL-ICs continue to renew themselves for longer periods (for example, 9 months) in primary recipients.

The estimated frequency of SL-ICs in the 7 cases studied was variable (0.2-41 SL-ICs per 106 leukemic blasts) and did not correlate with the FAB subtype or the number of CD34+ cells present in the donor. This quantitative assay will be useful for monitoring the efficiency of novel therapeutical strategies directly on leukemic stem cells.32 33

Although our series contains a small number of patients, data presented here provide functional in vivo evidence that the Ph1-ALL leukemic clone is organized as a hierarchy, because CD34++CD38− SL-ICs were able to generate large numbers of leukemic blasts that expressed the same aberrant combination of surface antigens typical of the patient sample.

Human Ph1-ALL originated from primitive CD34++CD38− hematopoietic cells

Since our data strongly support a hierarchical organization of the leukemic clone, the characteristics of the leukemic stem cell that maintain the clone provide the basis for identifying the original normal cell type from which the leukemic stem cell was derived. Using a similar transplantation strategy, a functional quantitative assay has been recently developed for SRCs.23,24 The SRC and SL-IC assays permit direct comparison of their biological properties, providing insight into the cellular origin of the Ph1-ALL disease. The SL-ICs were found exclusively in the primitive CD34++CD38− fraction of all patient samples regardless of the lineage markers expressed by the leukemic blasts, the percentage of blast cells expressing the CD34 antigen, or the FAB subtype. In this sense a recent report indicates that engraftment of AML samples into NOD/SCID mice was also obtained exclusively with CD34++CD38−cells.25 Thus, transformation at the level of committed progenitors may be the exception rather than the rule. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the target cell is a committed progenitor cell with low CD38 expression or that the particular cytokine combination used may have favored engraftment of CD38− cells. Obviously, and in view of the finding that some leukemias are present in utero,34 we cannot rule out the possibility that the target cell could be a totipotent stem cell. This possibility can now be explored using the new mouse models made by homologous recombination.35

It is remarkable that the SL-IC phenotype is so consistent in AML and Ph1-ALL. This uniformity of leukemic stem cell phenotype, together with the observation that primitive normal SRCs are also found in the CD34++CD38− fraction, argues strongly that leukemogenic events always occur in primitive cells and not in committed progenitors. Our inability to detect any SL-IC activity in the CD34+CD38+ fraction supports this idea. Thus, it seems that the leukemia originated in a primitive CD34++CD38− cell type. However, our data do not exclude the possibility that engraftment rather than leukemic stem cell activity correlates with a CD34++CD38−phenotype.

Data presented here suggest that a leukemia-initiating genetic event in Ph1-ALL might regularly occur at the stem cell level, irrespective of the phenotypic makeup of the bulk population of leukemic blasts. An explanation for our findings could be that the genetic defect itself determines the differentiation program of the affected cell clone, which contrasts with the opinion that the leukemic phenotype is a reflection of the level of the hematopoietic hierarchy at which the genetic defect occurs. Thus, our data support the hypothesis that the leukemogenic event most often occurs in a primitive cell16 and that the nature of this genetic defect itself determines the differentiation program of the leukemic clone. Although it is still unclear how a common progenitor cell becomes one type (lymphoid) rather than another, our results favor the idea that leukemic hematopoietic lineage determination is driven intrinsically (as described in stochastic models)36 rather than extrinsically (through external influences).

In conclusion, Ph1-ALL may be viewed as a differentiating system in which the SL-IC represents the most primitive leukemic stem cell. The suggestion that the SL-ICs originate from primitive normal stem cells provides a new framework for viewing the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie the heterogeneity seen in the leukemic blasts, particularly the impact that aberrant oncogene expression has on the development program of normal stem cells.1 This system will enable investigation of the biological function of different oncogenes in leukemic transformation, and will allow us to devise the new therapeutic strategies32,33 37 aimed at the leukemic stem cell.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Dr J. Dick for providing the p17H8 probe.

Supported by grants BMH4-CT96-0375 from the European Commission and DGCYT (UE96-0041, PB96-0816, and 1FD97-0360); by grant FIS 99/0935 and from the Fundación Cientı́fica of the AECC (Madrid, Spain); by grant 1 R01 CA79 955-01 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD); and by the Fundación Ferrer Investigación (C.C.).

C.C., N.G.-C., and J.P.-L. contributed equally to this work.

Reprints:I. Sánchez-Garcı́a, Departamento de Proliferación y Diferenciación Celular, Instituto de Microbiologı́a Bioquı́mica, CSIC/Universidad de Salamanca, Edificio Departamental, Avda del Campo Charro s/n, 37007 Salamanca, Spain; e-mail: isg@gugu.usal.es.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal