Abstract

The human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor consists of 2 glycoprotein subunits, GMR and GMRβ. GMR in isolation binds to GM-CSF with low affinity. GMRβ does not bind GM-CSF by itself, but forms a high-affinity receptor in association with GMR. Previously, it was found that N-glycosylation of GMR is essential for ligand binding. The present study investigated the role of N-glycosylation of the β subunit on GM-CSF receptor function. GMRβ has 3 potential N-glycosylation sites in the extracellular domain at Asn58, Asn191, and Asn346. Single mutants and triple mutants were constructed, converting asparagine in the target sites to aspartic acid or alanine. A single mutation at any of the 3 consensus N-glycosylation sites abolished high-affinity GM-CSF binding in transfected COS cells. Immunofluorescence and subcellular fractionation studies demonstrated that all of the GMRβ mutants were faithfully expressed on the cell surface. Reduction of apparent molecular weight of the triple mutant proteins was consistent with loss of N-glycosylation. Intact N-glycosylation sites of GMRβ in the extracellular domain are not required for cell surface targeting but are essential for high-affinity GM-CSF binding.

Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a hematopoietic cytokine that stimulates the proliferation of myeloid precursor cells and enhances the function of neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes.1 GM-CSF is secreted by a variety of tissue types and its elaboration is regulated by mediators of inflammation.2 The biologic functions of GM-CSF are initiated by interaction with its cell surface receptor that consists of 2 subunits, α (GMRα) and β (GMRβ). The α subunit is ligand specific and binds to GM-CSF with low affinity (equilibrium dissociation constant, kd = 1-10 nmol/L).3-6 The β subunit does not bind GM-CSF by itself, but forms a high-affinity receptor (kd = 20-100 pmol/L) with the α subunit.5,7-9 Both α and β subunits are members of a cytokine receptor superfamily characterized by 4 spatially conserved cysteine residues and a tryptophan-serine motif (WSXWS) in the extracellular domain.10 GM-CSF receptors are found on myeloid progenitors and mature myeloid cells including neutrophils, eosinophils, mononuclear phagocytes, and monocytes.5,11-14In addition, GM-CSF receptor subunits have also been found in normal nonhematopoietic tissues such as human placenta, endothelium, and oligodendrocytes of the central nervous system.15-17

Both GMRα and GMRβ are transmembrane glycoproteins. GMRα has an apparent molecular weight of 84 kd with all 11 potential asparagine-linked glycosylation (N-glycosylation) sites located in the extracellular domain of the receptor.3 The β subunit is a 130-kd protein.8 Analysis of the complementary DNA (cDNA)-deduced amino acid sequence of GMRβ suggests 7 potential N-glycosylation sites, 3 of which are in the extracellular domain at Asn58, Asn191, and Asn346. We previously showed that tunicamycin, an N-glycosylation inhibitor, completely abolished GM-CSF binding in COS cells expressing either low- or high-affinity GM-CSF receptor but did not affect cell surface expression of the α subunit.18Because tunicamycin treatment inhibited N-glycosylation of both α and β subunits in cotransfected COS cells, and unglycosylated GMRα subunit alone was unable to bind GM-CSF, the role of N-glycosylation of GMRβ in high-affinity binding has not been defined.

To investigate the function of N-glycosylation of the GMRβ subunit, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on the 3 potential N-glycosylation sites located in the β subunit extracellular domain. The asparagine residues Asn58, Asn191, and Asn346 in the consensus N-glycosylation sequence of Asn-X-Ser/Thr were converted to aspartic acid or alanine. Our results indicated that a single mutation in any of the 3 N-glycosylation sites, as well as triple mutations affecting all 3 sites, eliminated the activity of GMRβ in high-affinity GM-CSF binding when coexpressed with wild-type GMRα in COS cells. Thus, N-glycosylation of the β subunit is required for high-affinity GM-CSF binding of the α/β receptor complex.

Materials and methods

Construction of human GMRβ mutants

The cDNA encoding the wild-type human GMRβ was subcloned into pBluescript KS (pBKSGMRβ). The single mutants converting the target Asn to Asp were created by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the wild-type DNA template and 3 mutagenic primers that convert asparagine located at positions 58, 191, and 346 to aspartate:

•M1: 5′-CACCCGGCGAATGAGGGTCACGTCGACGAGCCGCTGGGCATC-3′

•M2: 5′-ATCCTCCTCTCCGACACCTCCCAGGCC-3′

•M3: 5′-GCTGTCTCCATCCTTGGTCACGTCGAGGGATGGAGGGGCCAT-3′

The other PCR primers were as follows:

•P1: 5′-CCCCCTCGAGGTCGACGGTATCGATAAGCTT-3′ (pBluescript KS polylinker sequence covering restriction sites Xho and EcoR V)

•P2: 5′-CCACTTGCTGGGACGTCCTGAGAGCCG-3′ (nt.661-687, anti-sense)

•P3: 5′-CACCTCCTTCCTCACCTCCCAGGA-3′ (nt.781-804, anti-sense)

•P4: 5′-CGGCTCTCAGGACGTCCCAGCAAGTGG-3′ (nt.661-687, sense)

•P5: 5′-GTGACCAAGGATGGAGACAGCTAC-3′ (nt.1039-1062, sense)

•P6: 5′-CTCTGTGGGTAGATCTGAGGCAGCTGG-3′ (nt.1666-1692, anti-sense)

To construct GMRβ-Asp58, a PCR fragment carrying the target mutation was made using primer M1 and primer P1 encoding the polylinker sequence of pBluescript KS located upstream of the initiation codon in pBKSGMRβ. The first PCR product was used as a primer to generate the mutated DNA fragment with another gene-specific primer P2 encoding the unique Aat II restriction site using the wild-type pBKSGMRβ as a template. The mutated DNA fragment from the second PCR reaction was digested with Xho I and Aat II and ligated into the cognate sites.

GMRβ-Asp191 was created in a manner similar to GMRβ-Asp58. The first PCR reaction used mutagenic primer M2 and the gene-specific primer P3. The PCR product was then used as a primer together with primer P1 in a second PCR reaction to synthesize a DNA fragment encoding Asp191. The mutated DNA fragment was subcloned into wild-type GMRβ sequences at the Xho I and Aat II restriction sites.

GMRβ-Asp346 was made by 3 PCR reactions. The first PCR was performed with mutagenic primer M3 and primer P4 encoding the Aat II site to generate a DNA fragment containing Asp346. In the second PCR, primer P5 was used with primer P6 containing the unique Bgl II restriction site to generate a DNA fragment with a sequence overlapping the first PCR product from nucleotide 1039 to nucleotide 1059. A DNA fragment containing restriction sites Aat II, Bgl II, and Asp346 was generated using the 2 PCR products from the previous steps as overlapping templates together with primer P4 and the primer P6. The third PCR product containing Asp346 was subcloned into the wild-type GMRβ gene using the unique Aat II and Bgl II restriction sites.

GMRβ-Asp58/191/346 was constructed using GMRβ-Asp191 as a basis. A double mutant encoding Asp58 and Asp191 was generated by the technique detailed above to create Asp58. A PCR product carrying the double mutant Asp58/191 was digested with XhoI and AatII and subcloned into the plasmid encoding the Asp346 mutation to generate GMRβ- Asp58/191/346.

The PCR reactions were carried out in a volume of 100 μL with Vent DNA polymerase buffer with 200 μmol/L dNTPs, 20 units of Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA) and appropriate primers and templates as described above. The reactions were incubated at 94°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 1.5 minutes, and 72°C for 3 minutes for 30 cycles. The identity and fidelity of all PCR-generated sequences for each mutant were confirmed by dideoxynucleotide sequencing.19 The cDNA of each mutant was excised from pBluescript and subcloned into a eukaryotic expression vector pMX (a gift from Genetics Institute, Inc, Cambridge, MA).18

To change the asparagine in the target N-glycosylation sites to alanine, the GMRβ mutants, GMRβ-Ala58, GMRβ-Ala191, GMRβ-Ala346, and GMRβ-Ala58/191/346 were constructed by PCR-based mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing (Retrogen, Inc, San Diego, CA).

Cell culture

Monkey kidney COS-1 cells were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% glutamine, and antibiotics.

Expression of membrane-bound human GM-CSF receptor in COS cells

Eukaryotic expression plasmids encoding the gene of human GMRα, the wild-type β, or the mutated β subunit were transfected into COS cells using a DEAE-dextran method20 or the LIPOFECTAMINE reagent (GIBCOBRL, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected COS cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS, 1% glutamine, and antibiotics with or without 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). COS cells were harvested 40 to 60 hours after transfection by incubation with 40 mmol/L EDTA in IMDM at 37°C for 30 minutes followed by adding an equal volume of IMDM containing 200 μg/mL chondroitin sulfate and 10% FBS. The mixture was then incubated at 37°C for a further 40 minutes.15

Immunoblotting of the β subunit

Cell membrane fractions were prepared using methods previously described.21 Equal amounts of protein obtained from membrane fractions of β-transfected COS cells were electrophoresed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-acrylamide gels and immunoblotted with a rabbit polyclonal antihuman GMRβ antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Receptor-binding assay

Kinetic binding assays were performed on transfected COS cells that were detached and disaggregated using 125I-labeled GM-CSF (DuPont, NEN, Boston, MA) in IMDM containing 10% FBS, 20 mmol/L EDTA, and 50 μg/mL chondroitin sulfate. Nonspecific binding was determined by the addition of 3 μmol/L unlabeled human recombinant GM-CSF (a gift from Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) to the assay mixtures. For equilibrium-binding kinetics, aliquots of cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of 125I-labeled GM-CSF at 4°C overnight. The assay mixtures were then layered over 0.5 mL bovine serum and centrifuged for 3 minutes at 10 000g. Radioactivity of the cell pellets was measured in a gamma counter. Equilibrium dissociation constants were determined by Scatchard analysis and analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Immunofluorescence staining of transfected COS cells expressing membrane-bound GMRβ

The COS-1 cells were grown and transfected with the plasmids encoding the gene of wild-type or mutated GMRβ on chamber slides. Forty-eight hours after transfection, slides were washed twice with PBS and air-dried at room temperature for 10 minutes. Slides were then fixed with cold acetone for 5 minutes and washed with PBS. The fixed cells were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antihuman GMRβ antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 hour and washed twice with PBS. Binding of the primary antibody was detected by incubation with a fluorescein-conjugated antirabbit Ig antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature. The stained cells were examined and photographed with confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Results

GMRβ N-glycosylation mutants are expressed on the surface of COS cells

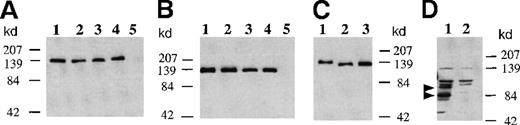

To determine whether GMRβ subunits with mutated extracellular N-glycosylation sites could be faithfully expressed on the cell surface, plasmids encoding the mutated β subunits were transfected into COS cells and the cell membranes were isolated. Membrane fractions enriched in plasma membrane were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-β subunit antibody. As shown in Figure1, a dominant band was detected at approximately 130 kd in the membrane fractions obtained from COS cells transfected with wild-type GMRβ and in each of the single mutations encoding Ala58, Ala191, Ala346 (Figure 1A) and the single mutations encoding Asp58, Asp191, Asp346 (Figure 1B) with similar levels of protein expression. The 130-kd band corresponded to the β subunit with complete posttranslational modification.8 The wild-type GMRβ and each of the GMRβ proteins altered at a single N-glycosylation site comigrated electrophoretically.

Expression of GMRβ N-glycosylation mutants in COS cell membranes.

Cells were transfected with expression plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ. Proteins isolated from the membrane fractions of COS cells 48 hours after transfection were loaded onto 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted with a rabbit antihuman GMRβ subunit antibody. (Panel A) One microgram of membrane protein from cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ was loaded in each lane: 1, wild-type GMRβ; 2, GMRβ-Ala58; 3, GMRβ-Ala191; 4, GMRβ-Ala346; 5, mock transfectant. The immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) with 1-minute exposure. (Panel B) Two micrograms of membrane protein from cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ were loaded in each lane: 1, wild type GMRβ; 2, GMRβ-Asp58; 3, GMRβ-Asp191; 4, GMRβ-Asp346; 5, mock transfectant. The immunoreactive bands were detected by ECL with 1-minute exposure. (Panel C) One microgram of membrane protein obtained from cells transfected with plasmid encoding wild-type or GMRβ-Ala58/191/346 was loaded in each lane: 1, wild-type GMRβ without tunicamycin treatment; 2, wild-type GMRβ treated with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin; 3, GMRβ-Ala58/191/346. The immunoreactive bands were detected by ECL with 1-minute exposure. (Panel D) Twenty micrograms of membrane protein obtained from cells transfected with plasmid encoding GMRβ-Asp58/191/346 (lane 1) and mock transfectant (lane 2) were loaded. The immunoreactive bands were detected by ECL with 15 minutes of exposure.

Expression of GMRβ N-glycosylation mutants in COS cell membranes.

Cells were transfected with expression plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ. Proteins isolated from the membrane fractions of COS cells 48 hours after transfection were loaded onto 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted with a rabbit antihuman GMRβ subunit antibody. (Panel A) One microgram of membrane protein from cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ was loaded in each lane: 1, wild-type GMRβ; 2, GMRβ-Ala58; 3, GMRβ-Ala191; 4, GMRβ-Ala346; 5, mock transfectant. The immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) with 1-minute exposure. (Panel B) Two micrograms of membrane protein from cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ were loaded in each lane: 1, wild type GMRβ; 2, GMRβ-Asp58; 3, GMRβ-Asp191; 4, GMRβ-Asp346; 5, mock transfectant. The immunoreactive bands were detected by ECL with 1-minute exposure. (Panel C) One microgram of membrane protein obtained from cells transfected with plasmid encoding wild-type or GMRβ-Ala58/191/346 was loaded in each lane: 1, wild-type GMRβ without tunicamycin treatment; 2, wild-type GMRβ treated with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin; 3, GMRβ-Ala58/191/346. The immunoreactive bands were detected by ECL with 1-minute exposure. (Panel D) Twenty micrograms of membrane protein obtained from cells transfected with plasmid encoding GMRβ-Asp58/191/346 (lane 1) and mock transfectant (lane 2) were loaded. The immunoreactive bands were detected by ECL with 15 minutes of exposure.

Treatment with tunicamycin resulted in a β subunit with an apparent molecular weight approximately 9 kd less than the fully N-glycosylated protein (Figure 1C, lane 2). The triple mutant GMRβ-Ala58/191/346 (Figure 1C, lane 3) comigrated with the β subunit expressed in tunicamycin-treated cells, suggesting that mutations in all 3 target sites disrupted N-glycosylation on GMRβ and that only the extracellular N-glycosylation sites of the β subunit are subject to modification. The results also suggest that, in contrast to the GMRα subunit, N-glycosylation accounts for less than 7% of the total molecular mass of the β subunit.18 These results are also consistent with a study using N-glycosidase F to deglycosylate GMRβ.22 Because the overall N-glycosylation level of GMRβ is small, the electrophoretic mobility of the β subunit was not detectibly affected by mutation at a single site.

The substitution of asparagine with aspartic acid of the 3 extracellular glycosylation sites resulted in a protein that, although presented on the cell surface (Figure 2I), was unstable and subject to degradation (arrows, Figure 1D, lane 1). Presumably, the alteration in charge introduced by the aspartate triple mutation affected protein stability.

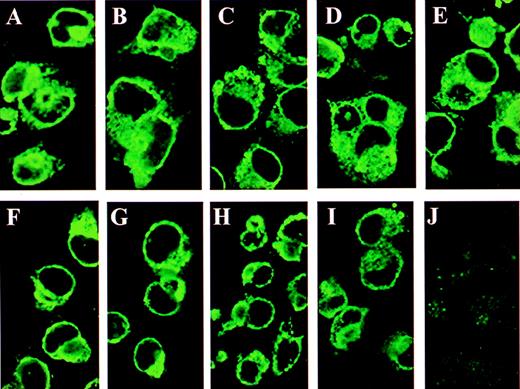

Immunofluorescence of GMRβ N-glycosylation mutants in COS cells.

The COS cells grown on chamber slides were transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ subunits and examined by immunofluorescence staining with a rabbit antihuman GMRβ subunit polyclonal antibody. (A) Wild type GMRβ; (B) GMRβ-Ala58; (C) GMRβ-Ala191; (D) GMRβ-Ala 346; (E) GMRβ-Ala58/191/346; (F) GMRβ-Asp58; (G) GMRβ-Asp191; (H) GMRβ-Asp346; (I) GMRβ-Asp58/191/346; (J) mock-transfectant.

Immunofluorescence of GMRβ N-glycosylation mutants in COS cells.

The COS cells grown on chamber slides were transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated GMRβ subunits and examined by immunofluorescence staining with a rabbit antihuman GMRβ subunit polyclonal antibody. (A) Wild type GMRβ; (B) GMRβ-Ala58; (C) GMRβ-Ala191; (D) GMRβ-Ala 346; (E) GMRβ-Ala58/191/346; (F) GMRβ-Asp58; (G) GMRβ-Asp191; (H) GMRβ-Asp346; (I) GMRβ-Asp58/191/346; (J) mock-transfectant.

To verify that mutation of the N-glycosylation sites of the GMRβ extracellular domain did not affect localization of the mutated GMRβ proteins to the cell membrane, COS cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type and mutated β subunits were examined by immunofluorescence staining with a polyclonal anti-GMRβ antibody (Figure 2). Plasma membranes of cells expressing wild-type (Figure 2A) and mutated β subunits (Figure 2B-I) demonstrated high-intensity fluorescence confirming the expression of GMRβ and all of the mutants on the cell surface. No fluorescence was observed in mock-transfected COS cells (Figure 2J).

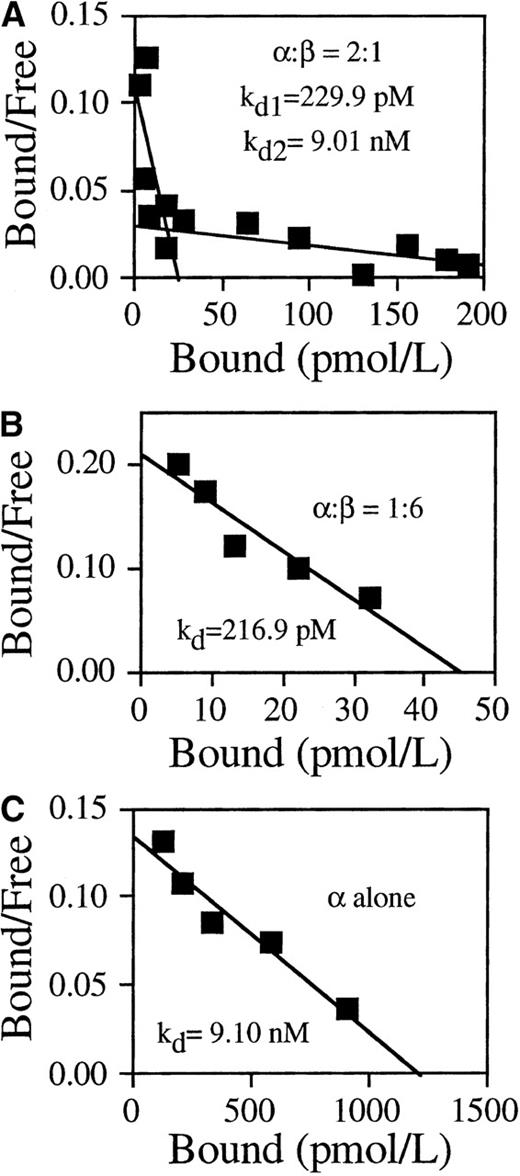

Expression of wild-type GM-CSF receptor in COS cells

To investigate the effect of N-glycosylation on the function of GMRβ, we first measured the GM-CSF binding activity of reconstituted wild-type receptor. COS cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids encoding wild-type GMRα and plasmids encoding GMRβ at different ratios. Equilibrium kinetic analyses were performed 48 hours after transfection. COS cells cotransfected with α and β subunits at a ratio of 2:1 expressed both high- (kd = 229.9 pmol/L) and low- (kd = 9.01 nmol/L) affinity binding sites (Figure 3A). When cotransfected with α/β at a ratio of 1:6, the transfected cells exclusively displayed high-affinity GM-CSF binding activity with a kd of 216.9 pmol/L (Figure 3B). COS cells expressing only wild-type GMRα displayed low-affinity binding with kd = 9.10 nmol/L (Figure 3C).

GM-CSF binding activity of wild-type receptors.

The COS cells were either transfected with GMRα alone or cotransfected with plasmids encoding GMRα and plasmids encoding GMRβ at the indicated ratios. 125I-labeled GM-CSF binding of the transfected cells was determined at 48 hours after transfection by Scatchard analysis. (A) α/β = 2:1, high-affinity kd = 229.9 pmol/L, low-affinity kd = 9.01nmol/L. (B) α/β = 1:6, kd = 216.9 pmol/L. (C) GMRα alone, kd = 9.10 nmol/L.

GM-CSF binding activity of wild-type receptors.

The COS cells were either transfected with GMRα alone or cotransfected with plasmids encoding GMRα and plasmids encoding GMRβ at the indicated ratios. 125I-labeled GM-CSF binding of the transfected cells was determined at 48 hours after transfection by Scatchard analysis. (A) α/β = 2:1, high-affinity kd = 229.9 pmol/L, low-affinity kd = 9.01nmol/L. (B) α/β = 1:6, kd = 216.9 pmol/L. (C) GMRα alone, kd = 9.10 nmol/L.

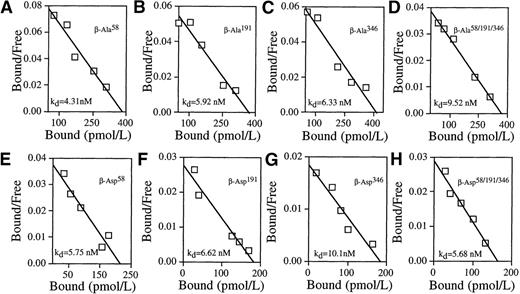

N-glycosylation of the extracellular domain of GMRβ is essential for high-affinity ligand binding activity of the GMR/β complex

Having established that GMRβ mutants at N-glycosylation sites were expressed on the cell surface and having defined transfection conditions yielding high-affinity binding, we examined the functional contribution of β subunits altered at N-glycosylation sites to GM-CSF binding. To ensure the reconstitution of a GMRα/β complex with the potential for high-affinity binding, plasmids encoding each mutated β subunit were cotransfected with plasmids encoding wild-type GMRα into COS cells at an α/β ratio of 1:6 and the GM-CSF binding activity was analyzed (Figure 4). Cells expressing β subunits that had been altered at any single site with either alanine or aspartate substitution (Ala58, Ala191, Ala346, or Asp58, Asp191, Asp346) as well as the triple mutants of GMRβ (GMRβ-Ala58/191/346, GMRβ-Asp58/191/346) exhibited low-affinity GM-CSF binding activity exclusively, identical to COS cells transfected with GMRα alone (Figure 3C). No high-affinity binding was detected in cells expressing any of the mutated GMRβ proteins. Equilibrium binding kinetics of cells transfected with each mutant and the wild-type receptor were measured by at least 3 independent experiments (Table 1). The data indicate that mutation of any 1 of the N-glycosylation sites in the GMRβ extracellular domain abolishes the ability of GMRβ to form a high-affinity receptor with GMRα. Thus, N-glycosylation of the β subunit is critical for high-affinity GM-CSF binding.

N-glycosylation site mutations in the extracellular domain of GMRβ prevent high-affinity GM-CSF binding in transfected COS cells.

The COS cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding wild-type GMRα and plasmids encoding mutated GMRβ at a ratio α/β = 1:6. Representative Scatchard analyses of GM-CSF binding data obtained from cotransfected cells are shown. (A) GMRβ-Ala58, kd = 4.31nmol/L. (B) GMRβ-Ala191, kd = 5.92 nmol/L. (C) GMRβ-Ala346, kd = 6.33 nmol/L. (D) GMRβ-Ala58/191/346, kd = 9.52 nmol/L. (E) GMRβ-Asp58, kd = 5.75 nmol/L. (F) GMRβ-Asp191, kd = 6.62 nmol/L. (G) GMRβ-Asp346, kd = 10.10 nmol/L. (H) GMRβ-Asp58/191/346, kd = 5.68 nmol/L.

N-glycosylation site mutations in the extracellular domain of GMRβ prevent high-affinity GM-CSF binding in transfected COS cells.

The COS cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding wild-type GMRα and plasmids encoding mutated GMRβ at a ratio α/β = 1:6. Representative Scatchard analyses of GM-CSF binding data obtained from cotransfected cells are shown. (A) GMRβ-Ala58, kd = 4.31nmol/L. (B) GMRβ-Ala191, kd = 5.92 nmol/L. (C) GMRβ-Ala346, kd = 6.33 nmol/L. (D) GMRβ-Ala58/191/346, kd = 9.52 nmol/L. (E) GMRβ-Asp58, kd = 5.75 nmol/L. (F) GMRβ-Asp191, kd = 6.62 nmol/L. (G) GMRβ-Asp346, kd = 10.10 nmol/L. (H) GMRβ-Asp58/191/346, kd = 5.68 nmol/L.

Ligand binding affinities of wild-type and mutated GM-CSF receptors expressed in COS cells

| Mutant . | kd (mean ± SD) . | Receptor affinity . |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type GMRαβ | 203.63 ± 58.03 pmol/L | High affinity |

| Wild-type GMRα | 6.38 ± 1.57 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala58 | 8.41 ± 1.88 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala191 | 8.90 ± 1.99 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala346 | 5.74 ± 1.65 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala58/191/346 | 7.10 ± 1.62 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp58 | 7.68 ± 2.27 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp191 | 6.69 ± 1.10 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp346 | 6.89 ± 1.87 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp58/191/346 | 7.59 ± 3.03 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| Mutant . | kd (mean ± SD) . | Receptor affinity . |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type GMRαβ | 203.63 ± 58.03 pmol/L | High affinity |

| Wild-type GMRα | 6.38 ± 1.57 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala58 | 8.41 ± 1.88 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala191 | 8.90 ± 1.99 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala346 | 5.74 ± 1.65 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Ala58/191/346 | 7.10 ± 1.62 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp58 | 7.68 ± 2.27 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp191 | 6.69 ± 1.10 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp346 | 6.89 ± 1.87 nmol/L | Low affinity |

| GMRβ-Asp58/191/346 | 7.59 ± 3.03 nmol/L | Low affinity |

Expression plasmids encoding the α subunit were transfected alone or cotransfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated β subunit to measure GM-CSF binding affinity. The data were derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

Asn-linked glycosylation is a major form of cotranslational modification in eukaryotic protein synthesis. N-glycosylation is observed in many proteins containing the sequence Asn-X-Ser/Thr in an appropriate context for recognition by oligosaccharyltransferases present in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus.23 The first step of N-glycosylation involves the transfer of a core oligosaccharide moiety, Glc3Man9GlcNAc2, from a lipid carrier to the asparagine residue in the nascent polypeptide chain in the rough ER. A series of trimming and modification steps are catalyzed subsequently by exoglycosidases and glycosyltransferases in the ER and, in some cases, in the Golgi compartments. The oligosaccharide processing reactions lead to the generation of different carbohydrate structures on the protein surface. High mannose oligosaccharides have a core of 3 to 9 mannose residues linked to the 2 N-acetylglucosamine residues (Man3-9GlcNAc2) attached to the asparagine residue in the consensus glycosylation motif of the protein. Complex oligosaccharides contain GlcNAc, galactose, or sialic acid additions to a Man3GlcNAc2 core, and hybrid oligosaccharides possess at least one of these additions on 1 branch of the core and mannose residues on the other branch of the core.23

The majority of membrane-bound and extracellular proteins in animals are N-glycosylated. The solubility and stability of the protein can be significantly affected by the carbohydrate groups on the outer surface of the protein molecule.24 The oligosaccharide moieties can also have dramatic effects on the biologic properties of glycoproteins such as ligand-binding affinity,25-29 signal transduction,30-33 immunogenicity,34,35 and clearance rate.36-40 In addition, N-glycosylation may be essential for proper protein folding and trafficking in the cells.41-44

In the case of the GM-CSF receptor, the molecular weights of the α and the β subunits calculated on the basis of the deduced amino acid sequence are 44 kd and 96 kd, respectively. The substantially higher apparent molecular weights observed for GMRα (84 kd) and GMRβ (130 kd) are in part due to N-glycosylation of these molecules.18 Previously, using the N-glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin, we showed that N-glycosylation is essential for the ligand binding activity of GMRα.18 Because the formation of high-affinity GM-CSF receptors requires the expression of both GMRα and GMRβ, and tunicamycin treatment blocks N-glycosylation in both receptor subunits, it was necessary to mutate the β subunit to evaluate the effect of N-glycosylation on the action of the β subunit. We therefore mutated the potential N-glycosylation sites in the extracellular portion of the β subunit. In 1 set of GMRβ mutants, the asparagines in the target sites were replaced by corresponding aspartic acids. To address the possibility that the negative charge introduced by the aspartate substitution might affect the biology of the β subunit irrespective of effects on N-glycosylation, the target asparagines were also converted to uncharged alanines. Nonetheless, we found that mutation of asparagine by either aspartate or alanine substitution in any of the potential N-glycosylation sites of the extracellular domain of GMRβ prevented high-affinity GM-CSF binding when the mutated GMRβ was coexpressed with the wild-type α subunit in COS cells.

In some cases, N-glycosylation is necessary for proper processing and intracellular transport of the protein. For example, mutation of N-glycosylation sites in the insulin receptor α subunit impairs cell surface expression of the receptor.43 Because immunofluorescence and Western blot studies showed that mutations in GMRβ did not affect cell surface expression of the β subunit, it was apparent that N-glycosylation of these sites is not required for plasma membrane targeting of GMRβ. Our previous studies indicated that the unglycosylated GMRα subunit can also be expressed on the cell surface.18

In contrast to GMRα, the contribution of N-glycosylation to the posttranslational modification of GMRβ is small, comprising approximately 25% of added molecular mass. The discrepancy between the apparent (130 kd) and the amino acid sequence deduced (96 kd) molecular weights of GMRβ may also arise from other posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation and O-glycosylation. The finding that tunicamycin treatment yields a β subunit of the same size as GMRβ mutated at the 3 extracellular N-glycosylation sites is a strong indication that only the extracellular sites are N-glycosylated. Although the size of the glycosylated moiety is small, the result that alteration of any of the 3 extracellular N-glycosylation sites abrogates high-affinity binding demonstrates that N-glycosylation is as important in the formation of the high-affinity receptor as it is in ligand binding to the low-affinity receptor.

The β subunit of the GM-CSF receptor alone does not bind ligand, but confers high-affinity ligand binding activity to the receptor in the presence of the ligand-specific GMRα subunit. Our findings indicate that N-glycosylation of the β subunit plays a crucial role in ligand binding by the high-affinity GM-CSF receptor complex. It is likely that the oligosaccharide moieties on the extracellular domain of GMRβ are essential for proper folding of the β chain and therefore development of the necessary conformation of the high-affinity ligand binding site. Removal of carbohydrate structures on the β chain prevents the interaction with GMRα that leads to high-binding energy. The data do not indicate, however, whether intact N-glycosylation is required for association of α and β subunits or whether the glycosylated moieties play a more direct role in ligand binding. Our recent observations regarding the role of the β subunit in ligand acquisition and release by the high-affinity receptor suggest a dynamic role for the extracellular domain of the β subunit.45

Other receptor systems have variable requirements for glycosylation. For example, the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor does not require glycosylation to bind its ligand human chorionic gonadotropin, whereas a closely related receptor, the follitropin receptor, does.46

Human GM-CSF is a 22-kd glycoprotein with a 4-helical bundle structure.47 Unglycosylated GM-CSF resulting from mutation of N- and O-glycosylation sites is biologically active.48In contrast, both the α and β subunits of the GM-CSF receptor require N-glycosylation to function. Thus, the carbohydrates present on the extracellular domains of the GM-CSF receptor appear to be essential for both ligand acquisition and high-affinity binding.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rong-Hua Zhang for excellent technical assistance and Elizabeth P. Koers for editing the manuscript.

Supported by grants RO1 CA30388, RO1 HL42107, P30 CA08748 from the National Institutes of Health, the Leukemia Society of America, and the Schultz Foundation.

Reprints:David W. Golde, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10021.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal