Abstract

Myelokathexis is a congenital disorder that causes severe chronic leukopenia and neutropenia. Characteristic findings include degenerative changes and hypersegmentation of mature neutrophils and hyperplasia of bone marrow myeloid cells. The associated neutropenia can be partially corrected by treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). These features led us to propose that accelerated apoptosis of neutrophil precursors might account for the neutropenic phenotype. Blood and bone marrow aspirates were obtained from 4 patients (2 unrelated families) with myelokathexis before G-CSF therapy and from 2 of the affected persons after G-CSF therapy (1 μg/kg per day subcutaneously for 3 weeks). Bone marrow was fractionated using immunomagnetic bead cell sorting into CD34+, CD33+/CD34−, and CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell populations. Examination of these cells by flow cytometry and electron microscopy revealed abundant apoptosis in the CD15+ neutrophil precursor population, characterized by enhanced annexin-V binding, extensive membrane blebbing, condensation of heterochromatin, and cell fragmentation. Colony-forming assays demonstrated significant reduction in a proportion of bone marrow myeloid-committed progenitor cells. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed a selective decrease inbcl-x, but not bcl-2, expression in the CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell population compared with similar subpopulations of control bone marrow-derived myeloid precursors. After G-CSF therapy, apoptotic features of patients' bone marrow cells were substantially reduced, and the absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) and expression ofbcl-x in CD15+/CD34−/CD33−cells increased. The authors concluded that myelokathexis is a disease characterized by the accelerated apoptosis of granulocytes and the depressed expression of bcl-x in bone marrow-derived granulocyte precursor cells. These abnormalities are partially corrected by the in vivo administration of G-CSF. (Blood. 2000;95:320-327)

Myelokathexis is a rare cause of severe chronic neutropenia characterized by degenerative changes and hypersegmentation in mature neutrophils, first described by Zuelzer in 1964.1 Subsequently, additional congenital and acquired cases have been reported.2-13 Affected persons have recurrent bacterial infections attributed to neutropenia and to depressed functional activity of their neutrophils.5,8 The pathophysiology underlying myelokathexis has been attributed to prolonged retention of neutrophils in the bone marrow compartment.1,2,14 Administration of either granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to persons with myelokathexis reportedly increases the number of neutrophils in circulation and leads to clinical improvement during episodes of bacterial infection.8 10-12

Tissue homeostasis during development and the host immune response are regulated by apoptosis, or programmed cell death.15,16 The apoptotic pathway involves a series of sequential morphologic and biochemical changes in affected cells, including early membrane blebbing (zeiosis) and redistribution of phospholipids in the plasma membrane, followed later by cytoplasmic shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and, ultimately, internucleosomal DNA fragmentation. Senescence cells are then removed by resident scavenger phagocytes.15-17

It is now clear that the apoptotic program in a particular cell or tissue can be regulated by either pro-apoptotic factors or anti-apoptotic factors.18,19 Recent evidence indicates that the Fas (APO-1; CD95)/Fas-ligand system is an important cellular pathway regulating the apoptotic program in diverse tissues,20-22 including the “professional” bone marrow-derived phagocytes.17,23-26 Among anti-apoptotic factors, the protein products of the protooncogenes bcl-2 andbcl-x have received considerable attention.27-31Based originally on morphologic examination of neutrophils and their precursors, we hypothesized that accelerated apoptosis of myeloid progenitor cells may account for the lack of peripheral neutrophils in myelokathexis. Therefore, we examined spontaneous apoptosis of myeloid progenitor cells from patients with myelokathexis and analyzed the expression pattern of genes implicated in apoptotic cell death in these respective cell populations. These studies showed that the accelerated apoptosis of bone marrow myeloid progenitors and the aberrant expression of bcl-x are central features of this disorder. Furthermore, these abnormalities can be abrogated in vivo by treatment with G-CSF.

Materials and methods

Clinical histories of patients with myelokathexis

Patient 1 (family 1).

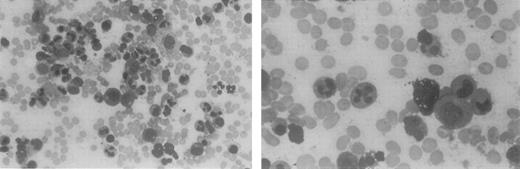

This 40-year-old woman was recognized as severely leukopenic and neutropenic when she was admitted to the hospital at age 5 with pneumonia. From early childhood through adulthood, numerous white blood cell counts of <1.0 × 109/L have been documented, with absolute neutrophil counts of 0.1 to 0.3 × 109/L and normal hemoglobin levels, hematocrits, and platelet counts. Her clinical history is remarkable for gingivitis and episodic cutaneous and sinopulmonary infections. Examination of bone marrow aspirates obtained from childhood through adulthood has revealed a hypercellular marrow with marked granulocytic hyperplasia. Bone marrow neutrophils in these aspirates contain hypersegmented nuclei with highly condensed chromatin. The nuclear lobes are often separated by long, thin strands of chromatin, consistent with the diagnosis of myelokathexis (Figure1). Many reticuloendothelial cells within the bone marrow contain basophilic material. Cytogenetic examination results on multiple occasions have been normal. At age 12, she had mild hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG, 525 mg/dL). The neutropenia was attributed to the ineffective production of neutrophils, based on a quantitative bone marrow biopsy and ferrokinetic studies performed in 1971.

Bone marrow aspirate from a patient with myelokathexis, revealing abundant cells of the neutrophil lineage.

Characteristic pyknotic nuclear lobes connected by fine chromatin filaments are present in the mature neutrophils.

Bone marrow aspirate from a patient with myelokathexis, revealing abundant cells of the neutrophil lineage.

Characteristic pyknotic nuclear lobes connected by fine chromatin filaments are present in the mature neutrophils.

Because of a nonhealing leg ulcer, G-CSF therapy (1–3 μg/kg per day) was initiated when she was 36, leading to increased blood neutrophil counts to approximately 2 × 109/L. The response, however, was associated with the development of anemia and thrombocytopenia, which resolved after the discontinuation of G-CSF. During treatment with G-CSF, the leg ulcer healed.

Patient 2 (family 1).

This 20-year-old son of patient 1 was recognized to have neutrophil counts of 0.1 to 0.5 × 109/L and hypogammaglobulinemia early in childhood. Like his mother, he had recurrent infections, including otitis media and otitis externa, severe chicken pox, gingivitis, and an episode of pneumonia. When he was 4 to 8 years of age, he was treated with intramuscular pooled IgG injections, which were discontinued because of allergic reactions. Cellulitis has often developed after relatively minor cuts or scratches, but serious infections have been infrequent during early adulthood. Hematologic data have been identical to those of his mother, including granulocytic hyperplasia in bone marrow aspirates and normal cytogenetics. Hematologic evaluation results of all other immediate family members were normal.

Patient 3 (family 2).

This 20-year-old woman has experienced recurrent ear and sinopulmonary infections since early childhood. At 2 years of age, she was found to have a white blood cell count of 0.3 to 0.7 × 109/L and to be severely neutropenic. In addition to recurrent bacterial infections, multiple warts have developed, particularly on her hands. The diagnosis of myelokathexis was based on the presence of granulocytic hyperplasia in bone marrow aspirates and on the observation of extremely pyknotic nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasms in both blood and bone marrow neutrophils. Hematocrit and platelet counts have been normal. Treatment with G-CSF at 3 μg/kg per day subcutaneously for 3 days increased blood neutrophils from 0.1 × 109/L to 0.5 × 109/L, but therapy was discontinued at the patient's request.

Patient 4 (family 2).

This 12-month-old daughter of patient 3 had severe leukopenia and neutropenia from birth. She has experienced recurrent sinopulmonary infections. The morphology of her neutrophils is identical to that of her mother. Because of recurrent infections she was treated with G-CSF (3 μg/kg per day), which increased the blood neutrophil count from 0.05 × 109/L to 1.0 × 109/L. G-CSF treatment was associated with the development of thrombocytopenia, which necessitated discontinuation of G-CSF. No other affected family members have been identified.

Blood and bone marrow samples

Blood samples and bone marrow aspirates were obtained from patients with myelokathexis and healthy volunteers after they gave informed consent and following a protocol approved by the Human Subjects Division of the University of Washington. The samples were stained with Wright Giemsa dye as described32 and examined for the proportion of cells with pyknotic nuclei by standard light microscopy.

Preparation of purified neutrophils

Neutrophils were isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples from patients and healthy volunteers by sequential sedimentation in Dextran T-500 (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ) in 0.9% sodium chloride, centrifugation in Histopaque-1077 (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes as described previously.25 These preparations contained >97% polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cell viability was >98% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Purification of bone marrow progenitor cells

The monocytoid cell fraction was isolated by modification of previously described methods.33 Bone marrow mononuclear cells from patients and healthy donors were fractionated into CD34+ early progenitors, CD33+/CD34−myeloid progenitors, and CD15+/CD33-/CD34− bone marrow granulocyte precursor subpopulations using specific monoclonal antibodies and immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Purity of each bone marrow hematopoietic subpopulation was >96% as tested by FACS analysis.

Culture conditions for bone marrow and neutrophils

Apoptosis assays.

Apoptosis of bone marrow cells and peripheral blood neutrophils was assessed by 2 methods, analysis of apoptotic (hypodiploid) nuclei by flow cytometry and annexin-V binding. For analysis of apoptotic nuclei, 5 × 106 phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–washed neutrophils were gently resuspended in 0.5 mL hypotonic fluorochrome solution 50 μg/mL propidium iodide in 0.1% sodium citrate and 0.1% Triton X-100 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Propidium iodide fluorescence of individual nuclei was filtered through a 585/42-nm band-pass filter and measured on a logarithmic scale by a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) while gating on physical parameters to exclude cell debris. Data were analyzed using CellFIT Cell-Cycle Analysis software (Becton Dickinson). At least 10,000 events per sample were counted. Results are reported as the percentage of cells with hypodiploid nuclei, which reflects the relative proportion of apoptotic cells.34-36 Annexin-V binding to neutrophils and bone marrow progenitor cells was performed using an apoptosis detection kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, 5 to 20 × 104 freshly isolated cells or cells stored overnight in RPMI (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) in the presence of 10% autologous serum were labeled with annexin-V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed twice, and analyzed by 2-color flow cytometry using CellQuest Analysis software (Becton Dickinson). Results are reported as a percentage of annexin-V–positive cells in early and late stages of apoptosis.

Colony-forming assays

Purified bone marrow CD34+ cells (3000 per plate) were plated in soft agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY) containing 5 × 10-5 mol/L 2β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and penicillin–streptomycin, supplemented with human recombinant hematopoietic growth factor mix (20 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL Flt3 ligand, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL G-CSF, and 10 ng/mL GM-CSF) in triplicate 1-mL plates at 3 × 103 cells/plate as described.37 The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. On day 15, the resultant colonies were evaluated based on morphology, density, and number of cells, and they were grouped into CFU–high proliferative potential primitive progenitor cells (>1000 cells/colony), early myeloid progenitors CFU-GM (>100 cells/colony), and late myeloid precursor CFU-GM clusters (<50 cells/colony). The results are presented as a percentage of primitive, early, and late myeloid compartments in the bone marrow, representing the mean number of morphologically distinct colonies in triplicate plates.

Electron and light microscopy

Bone marrow samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer for 2 hours, washed in the same buffer, and postfixed for 4 hours at room temperature in 2% osmium tetroxide in distilled water to which a few drops of 2% aqueous potassium–ferrocyanide were added. The tissue and cells were rinsed in distilled water, then block-stained with 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate for 20 minutes and again rinsed in distilled water. Cells were embedded in 2% agar in 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer. The tip of the agar blocks containing the cell pellet was cut off, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in Eponate 12 resin (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Samples of bone marrow tissue were directly dehydrated and embedded in resin without agar embedding. Thin sections were cut with a diamond knife on an LKB Nova ultramicrotome (LKB, Bromma, Sweden) and collected on parlodion-coated 200 mesh copper grids (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a JEOL JEM 100B electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical staining for bcl-2 and bcl-x

Immunohistochemical staining of CD34+, CD33+/CD34−, and CD34−/CD33− cell populations from patients with myelokathexis and healthy control volunteers was performed on cytocentrifuge preparations. Cells were fixed in 100% ethanol at 4°C for 10 minutes. Specimens were blocked with 5% normal goat serum diluted in Tris-buffered saline, pH 8, for 20 minutes at room temperature. The hamster-antihuman bcl-2 monoclonal antibody 6C8 or a hamster monoclonal antibody of irrelevant specificity TN3 19.12 (as a control IgG), adjusted to equal concentrations, was incubated with the specimens, followed by biotinylated goat-antihamster IgG (United States Biochemical, Medford Lakes, NJ) at a 1:40 dilution and ABC alkaline phosphatase reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Alternatively, rabbit polyclonal antihuman bcl-x antibody (gift of Dr. Craig Thompson, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL)38 or dilution buffer was incubated with the specimens, followed by biotinylated goat-antirabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) at a dilution of 1:40 and ABC alkaline phosphatase reagent. All incubations were performed at 4°C for 1 hour. The primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 5% normal goat serum. Staining was developed using bromochlorindoyl phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium substrate. Specimens were counterstained using 0.1% acridine orange and 0.1% safranin O. The RL7 cell line was used as a positive control for bcl-2expression.39 Unseparated normal mononuclear bone marrow cells were used as a positive control for bcl-x expression.

Immunofluorescence flow cytometry for detection of Fas expression

Cell surface expression of Fas on purified bone marrow precursor cells was assayed by direct immunofluorescence flow cytometry using saturating concentrations of FITC-conjugated Fas-specific UB2 monoclonal antibody. In brief, 106 freshly isolated cells were incubated in the presence of UB2-FITC monoclonal antibody for 45 minutes at 4°C, washed once with PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide, then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Simultaneous negative control staining reactions were performed with a saturating concentration of irrelevant murine IgG1-FITC in place of UB2-FITC. The plates were kept at 4°C until the stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan and BDIS Consort software (Becton Dickinson).

Immunofluorescence flow cytometry for detection of FasL expression

Cell surface expression of FasL on cells of interest was assayed by indirect immunofluorescence flow cytometry using Fas-Ig for primary staining and FITC-conjugated affinity-purified F(ab')2 goat-antihuman IgG for secondary staining. In brief, primary staining was performed with 106 cells incubated for 45 minutes on ice in the presence of Fas-Ig (20 μg/mL) in PBS containing 10% normal human serum. The cells were washed once with PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide and 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and a secondary staining was performed using FITC-conjugated affinity purified F(ab')2 goat-antihuman IgG (10 μg/mL) in PBS containing 10% goat serum. After a single PBS wash, the cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Simultaneous negative control staining reactions were performed by omitting Fas-Ig from the primary staining step. In separate neutrophil assays, B7-Ig was also substituted for Fas-Ig as a negative control. The plates were kept at 4°C until the stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence intensity was calculated by subtraction of the mean fluorescence channel of the appropriate negative control.

Results

Survival characteristics of peripheral blood neutrophils and bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors from patients with myelokathexis

To investigate whether the neutropenia in myelokathexis is caused by accelerated apoptosis, we first compared the viability and rate of apoptotic cell death of peripheral blood neutrophils and CD15+ bone marrow neutrophil precursors in vitro from patient 2 and a healthy control. No substantial differences in viability or in the level of apoptosis were present in freshly isolated neutrophils and in CD15+ cells from the myelokathexis patient and the healthy volunteer (Table1). However, examination of the cell populations after overnight storage revealed a substantially larger proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis in neutrophils and in CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cells from the patient with myelokathexis compared with the healthy volunteer. On overnight storage approximately 55% to 60% of peripheral blood neutrophils from the patient with myelokathexis developed features of apoptosis compared to only 10% to 20% of neutrophils from the healthy donor. Similarly, approximately 90% of bone marrow CD15+ cells from the patient with myelokathexis were apoptotic after overnight storage. In contrast, only 20% of the comparable cells from the healthy volunteer underwent apoptosis during this time period.

Comparison of peripheral blood neutrophils and CD15+ bone marrow cells from myelokathexis patient 2 and an H volunteer

| . | % Viability . | % Apoptosis Nuclei . | % Annexin V+ Cells . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h . | 16 h in vitro . | 0 h . | 16 h in vitro . | 0 h . | 16 h in vitro . | |

| I. Neutrophils | ||||||

| A. Normal | 99 | 97.5 | 0.6 | 8.2 | 0.2 | 21.7 |

| B. Myelokathexis | 98.5 | 38 | 2.8 | 53.7 | 3.2 | 62.3 |

| II. CD15+ BM Cells | ||||||

| A. Normal | 97.5 | 68 | 1.6 | 19.1 | 3.1 | 21.1 |

| B. Myelokathexis | 96.5 | 12 | 11.3 | 91.9 | 28.7 | 89.7 |

| . | % Viability . | % Apoptosis Nuclei . | % Annexin V+ Cells . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h . | 16 h in vitro . | 0 h . | 16 h in vitro . | 0 h . | 16 h in vitro . | |

| I. Neutrophils | ||||||

| A. Normal | 99 | 97.5 | 0.6 | 8.2 | 0.2 | 21.7 |

| B. Myelokathexis | 98.5 | 38 | 2.8 | 53.7 | 3.2 | 62.3 |

| II. CD15+ BM Cells | ||||||

| A. Normal | 97.5 | 68 | 1.6 | 19.1 | 3.1 | 21.1 |

| B. Myelokathexis | 96.5 | 12 | 11.3 | 91.9 | 28.7 | 89.7 |

To confirm the hypothesis that impaired survival of myeloid progenitors contributes to the neutropenic phenotype of myelokathexis, annexin-V–FITC–propidium iodide staining of bone marrow hematopoietic subpopulations and flow cytometry analysis was performed.40This method permits evaluation of cells in the early and late stages of apoptosis. The rate of apoptotic cell death was studied in freshly isolated cells and after storage overnight at 37°C. As shown in Figure 2, the rate of apoptotic cell death in freshly isolated cells did not differ significantly from control populations. However, overnight storage of myelokathexis cells at 37°C resulted in apoptosis of approximately 25% to 50% of CD34+ cells, up to 50% of CD33+/CD34− cells, and >30% of CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cells compared with 20%, 7%, and 10% apoptosis in respective cell populations from healthy volunteers. Peripheral blood neutrophils were also analyzed and revealed up to 70% cells undergoing spontaneous apoptosis on overnight storage compared with 25% in control (Figure2). These data demonstrate that the insufficient supply of neutrophils to the peripheral blood in myelokathexis is caused, at least in part, by accelerated apoptosis of bone marrow progenitor cells.

Percentage of purified bone marrow progenitor cells undergoing apoptotic cell death.

From healthy volunteers and patients with myelokathexis, as determined by FACS analysis of annexin-V–fluorescein isothiocyanate–propidium iodide–labeled cells. (open bars) Freshly isolated cells. (filled bars) Same cell populations stored overnight in 10% autologous serum. Data for control subpopulations represent mean value of 4 healthy volunteers ± SD.

Percentage of purified bone marrow progenitor cells undergoing apoptotic cell death.

From healthy volunteers and patients with myelokathexis, as determined by FACS analysis of annexin-V–fluorescein isothiocyanate–propidium iodide–labeled cells. (open bars) Freshly isolated cells. (filled bars) Same cell populations stored overnight in 10% autologous serum. Data for control subpopulations represent mean value of 4 healthy volunteers ± SD.

Characteristics of bone marrow progenitor cells in myelokathexis

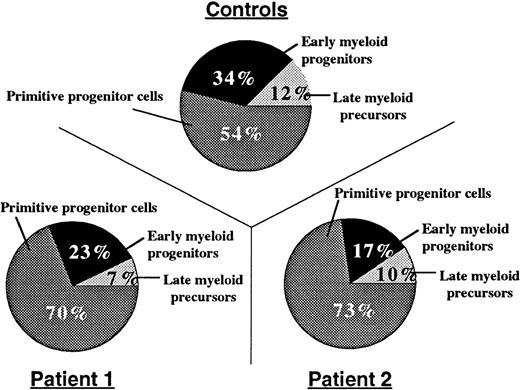

Bone marrow aspirates were hypercellular, and neutrophils were hypersegmented with nuclear lobes connected by thin filaments of chromatin (Figure 1). To determine the relative distribution of bone marrow myeloid compartments in patients with myelokathexis, we examined bone marrow CD34+ cells in colony-forming assays in soft agar in the presence of a cocktail of hematopoietic growth factors (SCF, Flt3 ligand, IL-3, G-CSF, and GM-CSF). On day 15, the resultant colonies were evaluated based on their morphology, density, and number of cells, and they were grouped into CFU-HPP (high proliferative potential primitive progenitor cells, more than 1000 cells/colony), early myeloid progenitors CFU-GM (more than 100 cells/colony), and late myeloid precursor CFU-GM clusters (<50 cells/colony). Colony-forming assays demonstrated that the proportion of CFU-HPP cells was increased, but the proportion of early and late CFU-GM cells was relatively decreased in patients with myelokathexis (Figure3). These data indicated a shift in the relative distribution of bone marrow myeloid compartments to more “primitive” cells in myelokathexis.

Compartments of bone marrow progenitor cells.

From healthy volunteers (n = 3) and 2 patients with myelokathexis, determined by colony-forming assays. 3 × 103 bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells, were plated on soft agar in the presence of hematopoietic growth factor mix, and the colony-forming units were assayed as described in Methods. Data represent the mean number of colonies from triplicate plates.

Compartments of bone marrow progenitor cells.

From healthy volunteers (n = 3) and 2 patients with myelokathexis, determined by colony-forming assays. 3 × 103 bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells, were plated on soft agar in the presence of hematopoietic growth factor mix, and the colony-forming units were assayed as described in Methods. Data represent the mean number of colonies from triplicate plates.

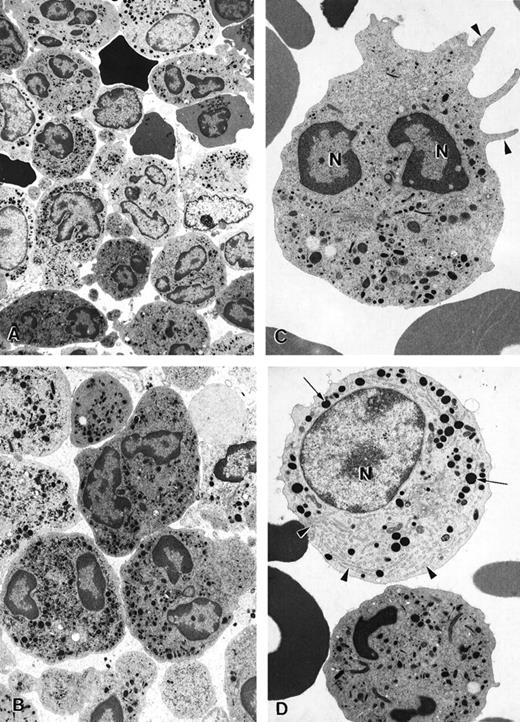

Electron microscopy of bone marrow cells in myelokathexis

The ultrastructure of bone marrow cells from patient 2 and a healthy volunteer donor was investigated before and during G-CSF therapy using electron microscopy (Figure 4). The bone marrow aspirate from a healthy volunteer contained predominantly neutrophils at various stages of maturation and immature red blood cells (Figure 4A; arrowheads). Few degenerating cells and minimal cellular debris were observed. In contrast, numerous degenerating cells (indicated by arrows) were present in the bone marrow aspirate from a patient with myelokathexis. In the degenerating cells, typical features of apoptosis were present, including the convoluted nucleus in an otherwise still intact cell. The granules (G) were aggregated, and the heterochromatin was concentrated in distinct, dense granular patches located on the inner surface of the nuclear membrane (Figure 4B). At higher magnification, apoptotic features such as cytoplasmic blebbing (arrowheads) and intense condensation of chromatin in the nucleus (N) were readily apparent in neutrophils (Figure 4). Macrophages were observed with numerous phagosomes that contained cellular debris as a result of phagocytizing senescent cells (Figure 4D). These apoptotic features were not present in the bone marrow aspirate from a healthy volunteer. These data indicated that accelerated apoptosis occurs in vivo in the myeloid precursor population in patients with myelokathexis.

Electron micrographs of bone marrow from patient 2 before granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment.

(A) Low magnification of the bone marrow shows degenerating cells (*), few mature neutrophils (**), and promyelocytes (arrows). Neutrophils with convoluted nuclei (arrowheads), a sign of early apoptosis, are observed. Magnification ×4000. (B) Macrophage in the bone marrow contains several phagosomes (arrows) with cellular debris of neutrophils. Neutrophil (arrowheads) with a distinguishable nucleus (*) and granules is discernible in 1 of the phagosomes. N, macrophage nucleus. Magnification ×6500. (C) Neutrophil in an early stage of apoptosis. The nucleus is convoluted (arrowheads), and the chromatin is condensed and distinctly circumscribed, forming dense granular masses (*) along the inner surface of the nuclear envelope. Magnification ×7500. (D) Neutrophil in a later stage of apoptosis. The cell shows cytoplasmic blebbing (arrowheads) and cellular fragmentation (arrow). N, nucleus. Magnification ×13,000. (E) Promyelocytes observed in the bone marrow. The cell at the bottom left appears normal and has a large, round nucleus (N), numerous granules, and a well-developed rough endoplasmic reticulum (arrows). The cell at the top right is apoptotic, as indicated by the fragmented nucleus (*), and has distinct areas of condensed chromatin (arrowheads). Magnification ×5500.

Electron micrographs of bone marrow from patient 2 before granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment.

(A) Low magnification of the bone marrow shows degenerating cells (*), few mature neutrophils (**), and promyelocytes (arrows). Neutrophils with convoluted nuclei (arrowheads), a sign of early apoptosis, are observed. Magnification ×4000. (B) Macrophage in the bone marrow contains several phagosomes (arrows) with cellular debris of neutrophils. Neutrophil (arrowheads) with a distinguishable nucleus (*) and granules is discernible in 1 of the phagosomes. N, macrophage nucleus. Magnification ×6500. (C) Neutrophil in an early stage of apoptosis. The nucleus is convoluted (arrowheads), and the chromatin is condensed and distinctly circumscribed, forming dense granular masses (*) along the inner surface of the nuclear envelope. Magnification ×7500. (D) Neutrophil in a later stage of apoptosis. The cell shows cytoplasmic blebbing (arrowheads) and cellular fragmentation (arrow). N, nucleus. Magnification ×13,000. (E) Promyelocytes observed in the bone marrow. The cell at the bottom left appears normal and has a large, round nucleus (N), numerous granules, and a well-developed rough endoplasmic reticulum (arrows). The cell at the top right is apoptotic, as indicated by the fragmented nucleus (*), and has distinct areas of condensed chromatin (arrowheads). Magnification ×5500.

Expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors in bone marrow precursor cells in myelokathexis

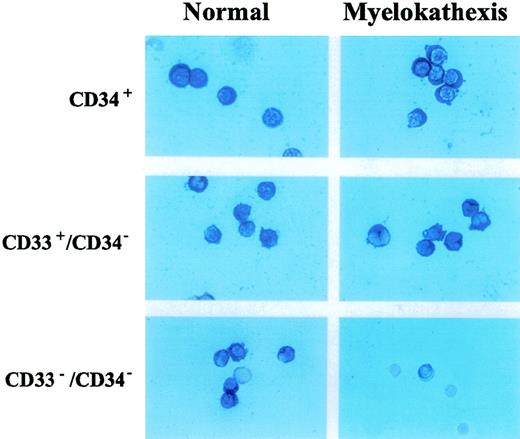

Neutrophils appear to be committed to apoptotic death in vitro and in vivo.17,26 This fate may result, at least in part, from constitutive coexpression of Fas and Fas ligand in neutrophils.17,23 26 Therefore, we examined and compared the expression of pro-apoptotic factors (ie, Fas and Fas ligand) and anti-apoptotic factors (ie, bcl-x and bcl-2) in bone marrow-derived cell populations from patient 2 and a healthy volunteer. Flow cytometry analysis revealed no difference in expression of either Fas or Fas ligand on CD37+, CD33+/CD34−, and CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell populations from patient 2 when compared with corresponding cell populations from the healthy volunteer (data not shown). Immunocytochemical analysis revealed the equivalent expression ofbcl-2 in these cells (data not shown). Expression ofbcl-x, however, was strongly and selectively decreased in the CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell population of patient 2 when compared with that of the healthy volunteer (Figure 5). A similar decrease inbcl-x expression was also observed in the corresponding cell population from patient 3 (data not shown). These data suggest that the depressed expression of bcl-x may contribute to increased apoptosis of neutrophil precursors in the bone marrow of patients with myelokathexis.

Immunocytochemical detection of bcl-x expression in CD34+, D33+/CD34−, CD34−/CD33− hematopoietic subpopulations purified from bone marrow of patient 2 and a healthy volunteer.

Immunocytochemical detection of bcl-x expression in CD34+, D33+/CD34−, CD34−/CD33− hematopoietic subpopulations purified from bone marrow of patient 2 and a healthy volunteer.

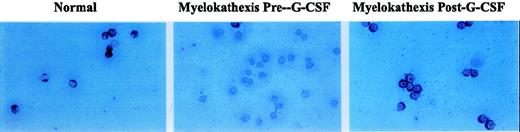

Effect of G-CSF treatment

Recombinant human G-CSF treatment resulted in significant increases in peripheral blood neutrophil counts (Table2). Using immunocytochemistry, the level ofbcl-x expression in the bone marrow-derived CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell population from patient 2 during G-CSF therapy was examined. Bcl-xexpression was scant or absent before G-CSF treatment (Figure6). However, in response to G-CSF treatment, bcl-x expression increased significantly to a level comparable to that observed in CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cells from the healthy person (Figure 6).

Absolute neutrophil counts of patients with myelokathexis in response to G-CSF treatment

| Subject . | Absolute Neutrophil Counts Before G-CSF Treatment (×109/L) . | Absolute Neutrophils Counts During G-CSF Treatment (×109/L) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 0.08 | 4.68 |

| Patient 2 | 0.05 | 0.92 |

| Patient 3 | 0.09 | 0.50 |

| Patient 4 | 0.08 | 0.96 |

| Subject . | Absolute Neutrophil Counts Before G-CSF Treatment (×109/L) . | Absolute Neutrophils Counts During G-CSF Treatment (×109/L) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 0.08 | 4.68 |

| Patient 2 | 0.05 | 0.92 |

| Patient 3 | 0.09 | 0.50 |

| Patient 4 | 0.08 | 0.96 |

Normal range of absolute neutrophil count: 1.80 − 7.00 × 109/L.

Immunocytochemical detection of bcl-x expression in bone marrow-derived neutrophil precursor CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cells of a normal volunteer and patient 2 before and during treatment with G-CSF.

Immunocytochemical detection of bcl-x expression in bone marrow-derived neutrophil precursor CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cells of a normal volunteer and patient 2 before and during treatment with G-CSF.

Effect of G-CSF treatment on survival characteristics of neutrophils and bone marrow-derived cell populations

Before G-CSF treatment, approximately 55% of peripheral blood neutrophils from patient 2 underwent spontaneous apoptosis during storage overnight in vitro. In contrast, only 10% apoptosis was observed in neutrophils from a healthy volunteer. During G-CSF treatment in vivo, the percentage of neutrophils from the patient with myelokathexis undergoing spontaneous apoptosis was substantially reduced. A similar effect of G-CSF treatment was observed for bone marrow cells in myelokathexis. During G-CSF treatment, the patient's bone marrow clearly contained fewer apoptotic neutrophils, as determined by electron microscopy (Figure7A). Round neutrophils, microvilli on the cell surface, and typically polymorphous nuclei were observed. Promyelocytes and an increased number of mature neutrophils were present, indicating the influence of G-CSF treatment (Figures 7B, 7C).

Electron micrographs of bone marrow cells from a myelokathexis patient 2 during granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment.

(A) Low-magnification image of bone marrow shows numerous differentiated neutrophils. Magnification ×3750. (B) Mature neutrophils in bone marrow observed at higher magnification appear normal and show negligible evidence of apoptosis. Magnification ×5000. (C) Mature neutrophil shows typical microvillar structures (arrowheads) on the cell surface. Nuclear lobes (N) appear normal and show regular chromatin distribution. Magnification ×7000. (D) Mature neutrophil (bottom) and promyelocyte (top) in the bone marrow. The promyelocyte contains extensive rough endoplasmic reticulum (arrowheads) and electron-dense granules (arrows). N, nucleus. Magnification ×7000.

Electron micrographs of bone marrow cells from a myelokathexis patient 2 during granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment.

(A) Low-magnification image of bone marrow shows numerous differentiated neutrophils. Magnification ×3750. (B) Mature neutrophils in bone marrow observed at higher magnification appear normal and show negligible evidence of apoptosis. Magnification ×5000. (C) Mature neutrophil shows typical microvillar structures (arrowheads) on the cell surface. Nuclear lobes (N) appear normal and show regular chromatin distribution. Magnification ×7000. (D) Mature neutrophil (bottom) and promyelocyte (top) in the bone marrow. The promyelocyte contains extensive rough endoplasmic reticulum (arrowheads) and electron-dense granules (arrows). N, nucleus. Magnification ×7000.

Discussion

Severe neutropenia is a well-recognized risk factor for the development of severe bacterial and fungal infections.41Patients with severe chronic neutropenia experience recurrent infections usually caused by surface organisms of the oropharynx, skin, and gastrointestinal tract. These infections are often associated with substantial morbidity. Several forms of severe chronic neutropenia have been described, including congenital, cyclic, autoimmune, idiopathic neutropenia, and myelokathexis.42 43

Myelokathexis is a rare cause of severe leukopenia and neutropenia.10-12 Inheritance of myelokathexis as an autosomal dominant trait is inferred from the pattern of occurrence in several families.42 Unlike most other forms of severe neutropenia, myelokathexis is characterized by granulocytic hyperplasia in the bone marrow, which contains neutrophils with cytoplasmic vacuoles, nuclear hypersegmentation, and pyknotic nuclear lobes connected by thin filaments. In addition, patients with myelokathexis are severely leukopenic, often with total leukocyte counts <1 × 109/L and absolute neutrophil counts 0.0 to 0.5 × 109/L. Higher leukocyte and neutrophil counts may be observed during infection. Susceptibility to infections is lower than it is in patients with cyclic or congenital neutropenia, perhaps because of the availability of large numbers of maturing neutrophils in the marrow and an increase in their survival resulting from the surge of endogenous cytokines and growth factors that occurs with acute infections.12

A common cellular defect in several forms of severe chronic neutropenia is “maturation arrest” of myeloid development in the bone marrow.44 For cyclic neutropenia, the degree of maturation arrest depends on which day in the cycle the marrow sample is obtained.45 For patients with congenital neutropenia, there is often an abundance of myeloblasts but few myelocytes and very few or no mature neutrophilic cells in the marrow. Viewed in more classic hematologic terms, the bone marrow examinations and some kinetic studies suggest that maturation arrest occurs because of ineffective granulocytopoiesis. In other words, the myeloid lineage can proliferate, but cells are lost during the process of differentiation and maturation in the bone marrow.

To investigate the cellular and molecular defects responsible for ineffective granulocytopenia in myelokathexis, we studied 4 patients from 2 unrelated families. The morphologic appearance of bone marrow-derived cells from these patients, as determined by light and electron microscopy, demonstrated that mature marrow and blood neutrophils, as well as myeloid-committed precursors, underwent degenerative changes that were characterized by profound apoptotic features, including extended cytoplasmic membrane blebbing, granule aggregation, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and intensive condensation of heterochromatin in the nucleus (Figure 4). Such apoptotic cells became hypofunctional and were removed from the intramedullary space by bone marrow macrophages through phagocytosis (Figure 4).

To delineate further the cell populations affected in myelokathexis, apoptosis studies were conducted with bone marrow-derived CD34+, CD33+/CD34−, and CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell populations. These studies demonstrated that the rate of spontaneous apoptotic cell death was accelerated in bone marrow-derived myeloid progenitor cells from these patients (Figure 2). Analysis of bone marrow CD34+ cells by colony-forming assay demonstrated a substantial reduction in the bone marrow pool of myeloid-committed progenitors in patients with myelokathexis (Figure 3). Taken together, these data indicate that accelerated apoptosis of myeloid-committed progenitor cells contributes to the marked reduction in delivery of neutrophils from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood in myelokathexis.

Accelerated apoptosis of bone marrow progenitor populations has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cytopenias associated with myelodysplastic syndromes.46,47 It has been shown that the ratio of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors may determine the survival capacity of a particular cell or tissue.18 19Therefore, the bone marrow-derived myeloid cells of neutrophil lineage (CD34+, CD33+/CD34−, and CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell subpopulations), separated according to the expression of cell surface antigens, were analyzed by flow cytometry and immunohistochemical staining for the expression profile of Fas, FasL, bcl-2, andbcl-x, all of which have been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis of hematopoietic cells. These studies revealed impaired expression of bcl-x in the bone marrow-derived CD15+/CD34−/CD33− cell population in myelokathexis (Figure 5). The expression levels of Fas, FasL, and bcl-2 in myelokathexis did not differ from respective control cell populations. These data indicate that the expression ofbcl-x is abnormally depressed in bone marrow-derived granulocyte precursor cells from patients with myelokathexis. The resultant disturbed balance in pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors may then drive accelerated apoptosis of the myeloid precursor cell population.

Successful G-CSF and GM-CSF treatment of patients with myelokathexis has been reported.10 42 In our patients, G-CSF therapy resulted in significant increases in peripheral blood neutrophil counts (Table 2). Analysis of apoptosis in peripheral blood neutrophils and bone marrow cells during G-CSF therapy revealed significant improvement in cell survival, providing evidence for G-CSF–mediated protection against apoptotic cell death.

During G-CSF therapy for bcl-x, immunohistochemical staining of bone marrow-derived CD34−/CD33−cells from a patient with myelokathexis demonstrated an increased number of cells positive for bcl-x expression (Figure 6). These data strongly suggest that G-CSF therapy resulted in an upregulation ofbcl-x gene expression, which is impaired in patients with myelokathexis. Furthermore, these observations implicate an important role for bcl-x expression in the regulation of cell survival during myeloid development, consistent with previous findings inbcl-x knockout mice.34

In summary, spontaneous apoptosis of myeloid progenitor cells is accelerated in myelokathexis. Expression of bcl-x, an important regulator of apoptosis in the hematopoietic system, is downregulated in this disorder. It is still unclear, however, whether the defective expression of the bcl-x gene in the bone marrow progenitor cells of patients with myelokathexis is a primary defect or a consequence of alterations in other genes involved in the regulation ofbcl-x expression or bcl-x-related pathways. In either case, the increase in bcl-x induced by G-CSF therapy is associated with the partial resolution of neutropenia and a marked improvement in the in vitro survival characteristics of peripheral blood neutrophils and bone marrow neutrophil precursors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs M. Kang, C. Hatlestad, A. Kattamis, J. Kwiatkowski, M. Wener, G. Segal, and M. Brouns, and they thank Audrey Anna Boyard of the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry for the referral of patients with myelokathexis. They also thank Linda Slane for help with manuscript preparation.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (2RO1-DK-18951) and Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA).

Reprints:David C. Dale, Department of Medicine, Box 356422, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-6422; e-mail:dcd@u.washington.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal