Abstract

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) is a leading cause of death in sickle cell disease (SCD). Our previous work showed that hypoxia enhances the ability of sickle erythrocytes to adhere to human microvessel endothelium via interaction between very late activation antigen-4 (VLA4) expressed on sickle erythrocytes and the endothelial adhesion molecule vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). Additionally, hypoxia has been shown to decrease the production of nitric oxide (NO) which inhibits VCAM-1 upregulation. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that during ACS, the rapidly progressive clinical course that can occur is caused by initial hypoxia-induced pulmonary endothelial VCAM-1 upregulation that is not counterbalanced by production of cytoprotective mediators, including NO, resulting in intrapulmonary adhesion. We assessed plasma NO metabolites and soluble VCAM-1 in 36 patients with SCD and 23 age-matched controls. Patients with SCD were evaluated at baseline (n = 36), in vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC; n = 12), and during ACS (n = 7). We observed marked upregulation of VCAM-1 during ACS (1,290 ± 451 ng per mL; mean ± 1 SD) with values significantly higher than controls (P < .0001) or patients either in steady state or VOC (P < .01). NO metabolites were concomitantly decreased during ACS (9.2 ± 1.5 nmol/mL) with values lower than controls (22.2 ± 5.5), patients during steady state (21.4 ± 5.5), or VOC (14.2 ± 1.2) (P< .0001). Additionally, the ratio of soluble VCAM-1 to NO metabolites during ACS (132.9 ± 46.5) was significantly higher when compared with controls (P < .0001) or patients either in steady state or VOC (P < .0001). Although hypoxia enhanced in vitro sickle erythrocyte-pulmonary microvessel adhesion, NO donors inhibited this process with concomitant inhibition of VCAM-1. We suggest that in ACS there is pathologic over expression of endothelial VCAM-1. Our investigations also provide a rationale for the therapeutic use in ACS of cytoprotective modulators including NO and dexamethasone, which potentially exert their efficacy by an inhibitory effect on VCAM-1 and concomitant inhibition of sickle erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion.

SICKLE CELL DISEASE (SCD) is a disorder whose protean manifestations are caused by the substitution of a single base in the gene encoding the human β-globin subunit.1Its reach is worldwide, affecting predominantly people of equatorial African descent, although it is also found in persons of Mediterranean, Indian, and Middle Eastern lineage. Although the episodic and unpredictable vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) or pain crisis is the hallmark of SCD, the acute chest syndrome (ACS) is the second most common cause of hospitalization and is a leading cause of both mortality and morbidity in this disease entity.2,3 Although clinically ACS is often a self-limited acute pulmonary illness whose typical features are chest pain, cough, dyspnea, fever, and pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray, the illness may rapidly progress to life-threatening respiratory insufficiency and total “white out” on chest radiographs. Multiple etiologic factors underlie this syndrome, including infection; hypoventilation (after surgery, rib infarcts, or narcotic administration for VOC); and pulmonary fat embolism from infarcted bone marrow.2-7 We propose and demonstrate preliminary observations linking these disparate etiologies of ACS into a more unifying hypothesis.

Our previous work has shown that hypoxia markedly enhances the ability of sickle erythrocytes to adhere to both macrovascular and microvascular endothelium via an interaction between the integrin α4β1, otherwise known as the very late activation antigen-4 (VLA-4), expressed on sickle reticulocytes and the endothelial adhesion receptor, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which was observed to be upregulated by hypoxia.8The pulmonary microcirculation is particularly vulnerable to changes in oxygenation. We propose that the rapidly progressive pulmonary findings in ACS are mediated in part by hypoxia and cytokine-induced pulmonary endothelial cell VCAM-1 upregulation and that this process is not counterbalanced by the release of cytoprotective mediators (including nitric oxide [NO]) that normally inhibits this endothelial VCAM-1 upregulation. The net result of this imbalance is massive intrapulmonary sickle red blood cell (RBC)-endothelial adhesion with its attendant pulmonary findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against VCAM-1 [CD106, (clone 1G11)], the isotypic control antibody (clone B-Z1), and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase were obtained from Immunotec, Inc (Westbrook, ME), Harlan Bioproducts for Science, Inc (Indianapolis, IN), and Sigma Immunochemicals (St Louis, MO), respectively.51Cr-Sodium chromate (400 to 1,200 mCi/mg) was purchased from New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). 3-Morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1), S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), oleic acid, sodium nitrite, nitrate reductase from Aspergillus niger, NADPH, adenosine, theophylline, indomethacin, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO). 2,3-Diaminonaphthalene was obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co (Milwaukee, WI). Tissue culture supplies were purchased from Clonetics Corp (San Diego, CA).

Patients.

The study population included 23 normal controls (age ranged from 2.75 to 30 years) and 36 patients with homozygous SS disease (age ranged from 2 to 23 years). Thirty-six patients were evaluated in steady state, and 12 were studied both during steady state and VOC. Seven were studied during episodes of ACS, 5 of whom were also evaluated during steady state. VOC was defined as an admission for pain which required parenteral narcotics, the patient being afebrile at the time of admission. ACS was defined as the development of a new infiltrate on chest radiography in combination with fever, respiratory symptoms, or chest pain, with the blood specimen being obtained before therapeutic transfusion or exchange. No infectious etiology was ascertained as the cause of ACS in this latter patient group.

Blood was drawn by a well-trained phlebotomist using a 2-syringe technique. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Committee for the protection of human subjects at St Christopher’s Hospital for Children (Philadelphia, PA). Blood was drawn by venipuncture from patients and control donors after informed consent. For minors, patient assent where appropriate was obtained in addition to parental permission. For analyses of soluble VCAM-1 and NO metabolites, blood was collected in acid-citrate-dextrose tubes containing NDGA, indomethacin, adenosine, and theophylline added to final concentrations of 25 μmol/L, 30 μmol/L, 100 mmol/L, and 1 mmol/L, respectively. Plasma was separated by centrifugation of anticoagulated blood samples at 735g for 10 minutes at room temperature (to remove the cellular elements of blood) followed by a second spin for 10 minutes at 11,750g at 4°C. All plasma samples were stored frozen at −80°C until assayed for both soluble VCAM-1 and NO metabolites. To prepare RBCs for the adhesion assay, blood was collected using sodium heparin as anticoagulant and the assay performed within 2 to 24 hours.

Culture of endothelial cells.

Both human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HLMECs) were obtained from Clonetics and cultured in Clonetics endothelial cell growth medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL human recombinant epidermal growth factor, 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, 50 ng/mL amphotericin B, 12 μg/mL bovine brain extract, and 2% (for HUVECs) or 5% (for HLMECs) fetal bovine serum. Cells were passaged using trypsin-EDTA as detailed in the protocol provided by the supplier (Clonetics), and cells from passages between 2 and 4 were used in the experiments described below.

RBC adherence assay.

Endothelial cells were plated at a density of 100,000 cells per well into wells of 12-well plates, and grown to confluence. Confluent endothelial cell monolayers were exposed to either room air (normoxia) or 1% O2 (hypoxia) for 24 hours, as previously described,8 in the presence or the absence of the indicated concentrations of the NO donors, 3-morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1; 10 and 100 μmol/L) or S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO; 0.1 and 1.0 mmol/L), or 30 μmol/L oleic acid. Cell monolayers were then tested in the static adherence assay of Hebbel et al.9 In brief,51Cr-labeled RBCs (0.5 mL, 2% hematocrit) were layered on washed endothelial monolayers. Incubations for 45 minutes at 37°C were conducted in the absence of plasma and the nonadherent RBCs removed. The monolayers were washed 5 times with 0.5 mL Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 1.3 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin buffered with 5 mmol/L N-2-hydroxy-ethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid. Adherent RBCs were determined by 51Cr release after cell lysis. Oleic acid was provided from 1,000X stocks prepared in ethanol. The control cells in the oleic acid study were treated with an equivalent amount of vehicle. The final ethanol concentration in the assay was constant at 0.1%. Individual data points represent the mean of triplicate values.

Measurement of soluble VCAM-1 in plasma.

Plasma levels of soluble VCAM-1 were measured using a commercially available ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of NO metabolites (nitrate and nitrite) in plasma.

Plasma samples were ultra-filtered using ultra-free MC microcentrifuge filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA) at 9,880g for 30 minutes. Nitrate present in the ultra-filtrate was reduced using nitrate reductase and the total nitrite was then assayed fluorometrically using 2,3-diaminonaphthalene.10 Standards from 10 to 1,000 pmol were measured for each assay, with the assay being reproducible and linear over this range.

Analysis of expression of VCAM-1 on endothelium by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Confluent HLMECs or HUVECs grown in wells of 12-well plate were exposed to hypoxia in the presence or the absence of SIN-1 (10 and 100 μmol/L) or 30 μmol/L oleic acid for 24 hours and assayed for the surface expression of VCAM-1 using a fluorescence ELISA.8

Data analyses.

Statistical evaluation was performed using the SigmaStat Statistical Package (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). All results are presented as the mean ± 1 SD. Because analyses of the data related to plasma sVCAM-1, NO metabolites, and the ratios of these plasma markers showed a nonparametric distribution, statistically significant changes in the levels of these plasma markers and their ratio were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis Test (for overall comparison). If the P value for this overall comparison was statistically significant at P< .05, group-wise comparisons were subsequently performed using the Mann-Whitney test. One-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test were used to compare the effects of NO donors on hypoxia-induced sickle RBC-HLMEC adhesion and VCAM-1 expression on HLMECs. The paired Student’s t-test was used to assess the effects of oleic acid on hypoxia-induced sickle RBC-HUVEC adhesion and VCAM-1 expression on HUVECs.

RESULTS

Plasma levels of soluble VCAM-1.

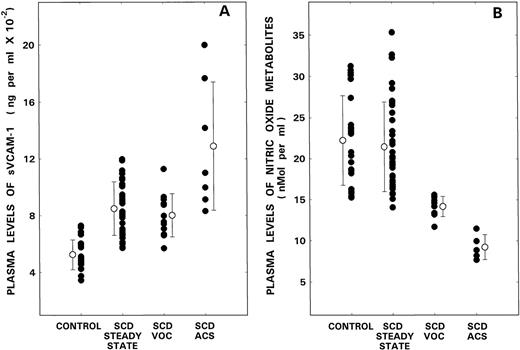

As depicted in Fig 1A, levels in the normal controls and patients with SCD in steady state, VOC, and ACS were 524 ± 104 (mean ± 1 SD), 850 ± 189, 802 ± 152, and 1,290 ± 451 ng/mL, respectively. Because the overall comparison of sVCAM-1 levels was statistically significant (P < .0001), further group-wise analyses of the data were performed. Although significant differences were observed between the controls and the various patient groups (P < .0001), there were no differences in the levels between the SCD patient in steady state and VOC. However, during ACS, levels of VCAM-1 were significantly increased when compared with both controls (P < .0001) or patients with SCD either in steady state (P < .01) or during VOC (P < .01).

Plasma levels of sVCAM-1 (A) and NO metabolites (B) from control donors are compared with those from patients with SCD during steady state, VOC, and ACS. Bars with open circles represent mean ± 1 SD values.

Plasma levels of sVCAM-1 (A) and NO metabolites (B) from control donors are compared with those from patients with SCD during steady state, VOC, and ACS. Bars with open circles represent mean ± 1 SD values.

Plasma levels of NO metabolites.

Figure 1B shows the levels of NO metabolites in control donors and patients with SCD. Although the mean value in the control population was 22.2 ± 5.5 (mean ± 1 SD) nmol/mL, levels in SCD patients in steady state, VOC, and ACS were 21.4 ± 5.5, 14.2 ± 1.2, and 9.2 ± 1.5 nmol/mL, respectively. Since the overall comparison of NO metabolite levels was statistically significant (P < .0001), further group-wise analyses of the data were performed. Although no differences were noted between controls and SCD patients in steady state, levels were significantly reduced during VOC (P < .0001). During ACS, an even further reduction in levels was noted when compared with either control values (P < .0001) or those obtained during VOC (P < .0001).

Ratio of soluble VCAM-1 to NO metabolites.

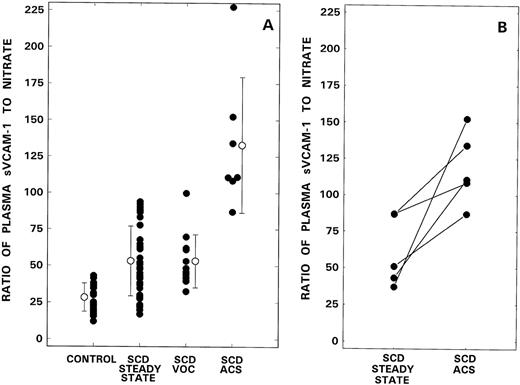

Figure 2A shows the sVCAM-1 to nitrate ratios in individual controls and in the various patient groups. While the mean ratio in the control population was 28.3 ± 9.6 (mean ± 1 SD), levels in SCD patients in steady state, VOC, and ACS were 53.2 ± 23.9, 53.2 ± 18.1, and 132.9 ± 46.5, respectively. Because the overall comparison was statistically significant (P < .0001), further group-wise analyses of data were performed. Although significant differences were observed between control and the various patient groups (P < .0001), there were no differences between the SCD patients in steady state and VOC. However, during ACS, the ratio was significantly elevated when compared to both controls (P < .0001) or patients with SCD, either in steady state (P < .0001) or VOC (P < .0001). In the 5 patients who were studied both at baseline and during ACS, paired data (Fig 2B) showed a significant increase in the sVCAM-1 to NO ratio during ACS (P < .03).

Ratio of soluble VCAM-1 to NO metabolites from control donors are compared with those from patients with SCD during steady state, VOC, and ACS (A). Bars with open circles represent mean ± 1 SD values. (B) The data in 5 patients evaluated both during steady state and ACS.

Ratio of soluble VCAM-1 to NO metabolites from control donors are compared with those from patients with SCD during steady state, VOC, and ACS (A). Bars with open circles represent mean ± 1 SD values. (B) The data in 5 patients evaluated both during steady state and ACS.

Effects of NO donors and oleic acid on hypoxia-induced sickle erythrocyte endothelial adhesion and VCAM-1 expression.

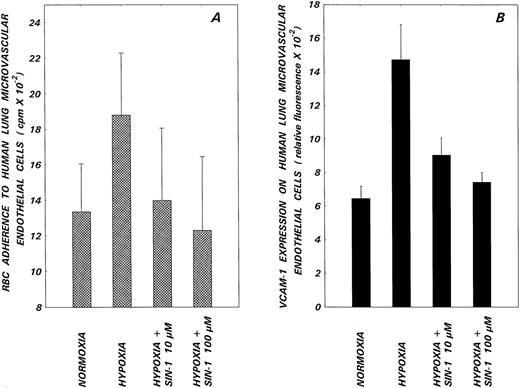

To test the hypothesis that NO functioned as a modulator of hypoxia-induced sickle RBC-endothelial cell adhesion, human pulmonary microvascular endothelium was exposed to hypoxia in the presence or absence of varying concentrations of the NO donors SIN-1 and GSNO, and cell monolayers were subsequently evaluated for adhesion. Hypoxia enhanced sickle RBC adhesion to the microendothelium by 45% ± 31% (mean ± 1 SD, N = 8, P < .01, Fig 3A). The NO donor SIN-1 inhibited this hypoxia-induced adhesion in a dose-dependent manner with mean inhibitory effects of 88% (P < .05) and 100% (P < .01) noted at SIN-1 concentrations of 10 and 100 μmol/L, respectively. GSNO (0.1 and 1 mmol/L), the other NO donor evaluated, also induced similar inhibitory effects on hypoxia-induced adhesion (data not shown). In concomitant experiments, pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells were assessed for VCAM-1 expression by ELISA. Results presented in Fig 3B show that hypoxia upregulated VCAM-1 expression by 127% ± 15% (mean ± 1 SD). This hypoxia-induced receptor expression was inhibited by 69% and 88% (P < .05) in the presence of 10 and 100 μmol/L SIN-1, respectively, thus paralleling the inhibitory effects of this NO donor on functional adhesion.

Effects of the NO donor, SIN-1, on hypoxia-induced sickle RBC adherence (A) and VCAM-1 expression (B) on HLMECs. Endothelial cell monolayers were subjected to hypoxia in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of SIN-1 for 24 hours and then assessed for sickle RBC adherence and VCAM-1 expression. Values presented are the means ± 1 SD from 8 (RBC adherence) or 3 (VCAM-1 expression) experiments. Differences observed in RBC adhesion (A) and VCAM-1 expression (B) between normoxic, hypoxic, and hypoxic plus SIN-1–treated groups were significantly different as assessed by one-way analysis of variance (P < .01).

Effects of the NO donor, SIN-1, on hypoxia-induced sickle RBC adherence (A) and VCAM-1 expression (B) on HLMECs. Endothelial cell monolayers were subjected to hypoxia in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of SIN-1 for 24 hours and then assessed for sickle RBC adherence and VCAM-1 expression. Values presented are the means ± 1 SD from 8 (RBC adherence) or 3 (VCAM-1 expression) experiments. Differences observed in RBC adhesion (A) and VCAM-1 expression (B) between normoxic, hypoxic, and hypoxic plus SIN-1–treated groups were significantly different as assessed by one-way analysis of variance (P < .01).

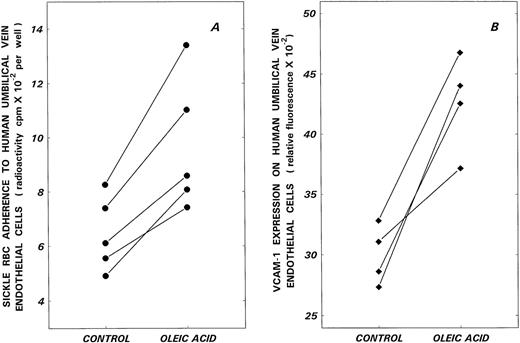

Finally, the effects of oleic acid on sickle RBC-endothelial adhesion and VCAM-1 expression on HUVECs are depicted in Fig 4. While hypoxia increased basal adhesion by 42% ± 9% (mean ± 1 SD), 30 μmol/L oleic acid further enhanced hypoxia-induced adhesion by 50% (P < .005, N = 5). Concomitant with this increase in functional adhesion, hypoxia-induced VCAM-1 expression on HUVECs was further upregulated by 42% in the presence of oleic acid (P < .02, N = 4).

Effects of oleic acid on hypoxia-induced sickle RBC adherence (A) and VCAM-1 expression (B) on HUVECs. Endothelial cell monolayers were subjected to hypoxia in the absence (control) or presence of 30 μmol/L oleic acid (oleic acid) for 24 hours and then assessed for sickle RBC adherence and VCAM-1 expression.

Effects of oleic acid on hypoxia-induced sickle RBC adherence (A) and VCAM-1 expression (B) on HUVECs. Endothelial cell monolayers were subjected to hypoxia in the absence (control) or presence of 30 μmol/L oleic acid (oleic acid) for 24 hours and then assessed for sickle RBC adherence and VCAM-1 expression.

DISCUSSION

The rate of polymerization of sickle hemoglobin and the capillary transit time of sickle erythrocytes play pivotal roles in the pathophysiology of the vaso-occlusive event in SCD.11Research into the latter process achieved prominence after the observation of Hebbel et al,9 who showed increased adherence of sickle erythrocytes to vascular endothelium, thus effectively prolonging capillary transit time. The molecular interactions that underlie this adherence process have been the subject of intensive investigation.12 To date, the main receptors on the microendothelium that have been shown to participate in adherence include VCAM-1 and CD36. The major erythrocyte counter-receptors include the integrin complex α4β1 and CD36, respectively, with the presence of these receptors, for the most part, on the surface of sickle reticulocytes rather than on the mature RBC. The adhesinogenic potential of sickle cells is further enhanced by several plasmatic factors such as thrombospondin, fibronectin, and von Willebrand factor, which act as ligands facilitating the process of adhesion.

Because tissue hypoxia is an integral part of the pathophysiology of SCD, our previous studies centered around the effects of hypoxia on sickle RBC-endothelial adherence. We have shown that hypoxia enhances adherence, and that the specific receptor pair involved in modulating hypoxia-induced adherence is the interaction between the sickle reticulocyte integrin complex α4β1 and VCAM-1 present on the microendothelial cell surface.8VCAM-1, which belongs to the Ig superfamily, contains 7 Ig-like domains, the ligand binding site for the integrin α4β1 being located within the NH2-terminal first domain.13 VCAM-1 is expressed only at low levels on vascular endothelial cells under basal conditions, being upregulated by cytokines such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α, endothelin-1, and hypoxia8 14-17(thus markedly increasing sickle RBC-endothelial adhesion via the previously noted α4β1: VCAM-1 coupling). A soluble form of VCAM-1 has also been described.

A variety of modifying mechanisms, including the signaling molecule NO, is called into play, in vivo, to counteract the detrimental consequences that could potentially result from unopposed endothelial VCAM-1 upregulation. Besides the well-known effects of NO, which induces smooth muscle cell relaxation and inhibition of platelet activation via stimulation of guanylyl cyclase,18 NO has also been shown to decrease cytokine-induced endothelial activation by repression of VCAM-1 gene transcription.19 While this anti–VCAM-1 effect was initially postulated to enhance the anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of this potent signaling molecule (by inhibition of leukocyte and monocyte adhesion to the vessel wall), our parallel studies elucidating the crucial role of VCAM-1 in mediating hypoxia-induced erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion makes NO a prime cytoprotective mediator in inhibition of hypoxia-induced RBC vascular adhesion.

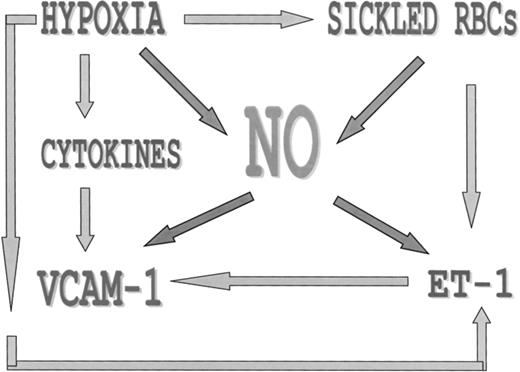

There are, however, unique circumstances that are called into play in sickle cell disease, and in particular in the ACS that disrupts the balance between this major cytoprotective mediator and the counter-regulatory forces that cause endothelial activation and VCAM-1 upregulation (Fig 5). The pulmonary microcirculation is particularly vulnerable to changes in oxygenation such that infection or hypoventilation of a segment or lobe could result in fairly rapid and extensive hypoxia-induced changes, including vasoconstriction, local cytokine and endothelin-1 release, and subsequent VCAM-1 upregulation.3,17,19 Moreover, in sickle cell disease there are a number of factors that could blunt the response of the cytoprotective molecule NO. Although hypoxia itself inhibits NO production by decreasing protein levels of constituitive NO synthase in endothelial cells,20 sickled erythrocytes specifically have been shown to inhibit NO by a similar mechanism.21 Additionally, exposure of endothelial cells to sickled RBCs results in a 4- to 8-fold increase in transcriptional induction of the gene encoding endothelin-1 in vitro, which could lead to further feedback vasoconstriction and VCAM-1 upregulation.22 Most recently, sickled RBCs have also been shown to upregulate nuclear NFkB levels, leading to endothelial cell activation (including VCAM-1 upregulation) and tissue factor expression.23

Factors in the ACS that contribute to intrapulmonary erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion are depicted. Hypoxia induces cytokine and endothelial-1 release, which singly and in combination upregulate VCAM-1. NO acts as a cytoprotective mediator that inhibits both endothelin-1 production and endothelial VCAM-1 expression under normal circumstances. However, during the pathophysiology of sickle cell ACS, sickled RBCs and hypoxia can both inhibit NO production (by decreasing cNOS transcription), leading to unopposed VCAM-1 upregulation and consequent RBC-endothelial adhesion.

Factors in the ACS that contribute to intrapulmonary erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion are depicted. Hypoxia induces cytokine and endothelial-1 release, which singly and in combination upregulate VCAM-1. NO acts as a cytoprotective mediator that inhibits both endothelin-1 production and endothelial VCAM-1 expression under normal circumstances. However, during the pathophysiology of sickle cell ACS, sickled RBCs and hypoxia can both inhibit NO production (by decreasing cNOS transcription), leading to unopposed VCAM-1 upregulation and consequent RBC-endothelial adhesion.

The findings we present in this report support our hypothesis. While the levels of soluble VCAM-1 were elevated to a similar extent in patients with SCD in both steady state and vaso-occlusive crisis (signifying some expected degree of endothelial cell activation in this disorder), VCAM-1 levels in the ACS were significantly higher than in the other patient groups. In parallel with this finding, we demonstrate that in patients with ACS, plasma levels of the NO metabolites were most significantly decreased. While previous published studies on the production of NO metabolites in SCD have provided discrepant results,24,25 no previous evaluation of these metabolites has been documented in ACS, except for a very recent abstract that supports our present findings.26 Our results show an unequivocal decrease during ACS of this crucial cytoprotective mediator. Additionally, when the ratio of the plasma markers (VCAM-1 to NO metabolites) was calculated, the highest ratios were observed in patients with ACS, with significant increases over baseline in those patients assessed both during steady state and and during ACS.

To further test our hypothesis that NO could function as a regulator of hypoxia-induced sickle erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion to the pulmonary microvessels, we evaluated the effects of 2 NO donors SIN-1 and GSNO on in vitro hypoxia-induced adhesion using cells from this circulatory bed. We have shown that these NO donors (at concentrations of NO that theoretically could be generated in vivo under conditions of inflammation)19 reverse hypoxia-induced sickle erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion in parallel with inhibition of hypoxia-induced upregulation of VCAM-1. Thus, the dramatic beneficial effects that have been previously reported27 for inhaled NO in 2 patients with severe ACS could be due not only to a reduction in pulmonary ventilation-perfusion mismatch and its effect on augmenting the oxygen affinity of sickle erythrocytes in vivo,28 but also to its specific anti-adhesiogenic potential under conditions of hypoxia (Fig 5).

Our final studies on oleic acid were performed since previous reports have documented pulmonary fat embolism as a cause of ACS7and since elevated levels of secretory phospholipase A2have been observed in this syndrome.29 These findings suggest a potential relationship between free fatty acids and ACS; in fact, oleic acid (which has been found to be increased in ACS)30 has been used in an animal model to simulate acute lung injury, with improvement of gas exchange after inhalation of NO.31,32 In keeping with our hypothesis, we show that this fatty acid also upregulated endothelial VCAM-1 expression and enhanced sickle RBC-endothelial adhesion. Additionally, a recent report suggests a beneficial effect of dexamethasone in modifying the severity of ACS.33 While the salutary effect of dexamethasone in this report was attributed to its inhibition of phopholipase A2and to its anti-inflammatory properties, this steroid also prevents the cytokine-induced expression of VCAM-1 on endothelium.34

In summary, we have shown that during the ACS a marked upregulation of endothelial cell VCAM-1 occurs, with a concomitant significant decrease in NO metabolite production. These findings, together with our in vitro demonstration that NO donors reverse hypoxia-induced sickle RBC-endothelial adhesion by downregulation of hypoxia-induced VCAM-1, suggests that in ACS massive intrapulmonary sickle erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion occurs due to hypoxia- and cytokine-induced VCAM-1 upregulation that is not counterbalanced by the compensatory production of cytoprotective mediators including NO. The role of the other cellular elements of blood, particularly neutrophils (that could also adhere to the pulmonary microvasculature primed by ACS-induced hypoxemia), needs further elucidation, as do other mechanisms of RBC endothelial adhesion, including the recently described property of phosphatidylserine positive erythrocytes to adhere to vascular endothelium.35

Supported by Grants No. HL51497 and 1P60HL62148 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Marie J. Stuart, MD, Department of Pediatrics, College Bldg #727, Thomas Jefferson University Medical College, 1025 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19107.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal