Abstract

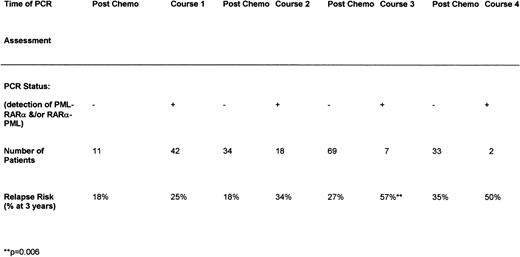

All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) is an essential component of the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), but the optimal timing and duration remain to be determined. Molecular characterization of this disease can refine the diagnosis and could be potentially useful in monitoring response to treatment. Patients defined morphologically to have APL were randomized to receive a 5-day course of ATRA before commencing chemotherapy or to receive daily ATRA commencing with chemotherapy and continuing until complete remission (CR). The chemotherapy was that used in current MRC Leukaemia Trials. Outcome comparisons were by intention to treat with additional analysis for relevant risk factors. Patients were characterized by molecular techniques for the fusion products of the t(15;17) and monitored by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) during and after treatment. Two hundred thirty-nine patients were randomized. Treatment with extended ATRA resulted in a superior remission rate (87% v 70%, P < .001), due to fewer early and induction deaths (12% v 23%, P = .02), and less resistant disease (2% v 7%, P = .03), which was associated with a significantly more rapid recovery of neutrophils and platelets. Extended ATRA reduced relapse risk (20%v 36% at 4 years, P = .04) and resulted in superior survival (71% v 52% at 4 years, P = .005). Presenting white blood cell count (WBC) was a key determinant of outcome. The 70% of patients who presented with a WBC less than 10 × 109/L had a better CR (85% v62%, P = .0001) and reduced relapse risk (22% v42%, P = .002) and superior survival (69%v 43%, P < .0001). Within the low count group, extended ATRA resulted in a better CR (94% v 76%, P= .001), reduced relapse risk (13% v 35%, P = .04), and improved survival (80% v 57%, P = .0009). There was no evidence of benefit in patients presenting with a higher WBC (>10 × 109/L). Molecular monitoring after the third chemotherapy course had a correlation with risk of relapse. The relapse risk was 57% if the RT-PCR was positive versus 27% if the RT-PCR was negative (P = .006). APL patients who present with a low WBC derive substantial benefit from combining ATRA with induction chemotherapy until remission is achieved, whereas patients with a higher WBC did not benefit. Molecular characterization of disease can improve diagnostic precision and a positive RT-PCR after consolidation identifies patients at a higher risk of relapse.

ACUTE PROMYELOCYTIC leukemia (APL) is associated with the reciprocal translocation, t(15;17)(q22;q21),1 leading to the formation ofPML-RARα and RARα-PML fusion genes,2and is characterized by a unique sensitivity to the differentiating agent (All-trans retinoic acid [ATRA]). It has been recognized for some time that this acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtype, even when only characterized morphologically (as French-American-British [FAB] M3), has a more favorable survival than other subgroups when treated with chemotherapy.3 However, the coagulopathy associated with induction was a significant cause of death4,5 that was additional to the usual risks of cytopenia as a result of chemotherapy. Although the risk of relapse was lower than in other groups, the majority of patients still died of recurrent leukemia.3

The introduction of ATRA into clinical practice immediately offered the potential to circumvent some of these obstacles. First, the associated coagulopathy resolved promptly, ie, usually within the first 48 hours, and remission could be achieved in a high proportion of patients without inflicting marrow hypocellularity.6-8 However these remissions were not durable and disease detected by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) usually remained.9,10 Subsequent studies used ATRA to induce remission and then introduced chemotherapy as consolidation.11-14 This approach significantly improved disease outcome, although retinoid treatment was not without complications. ATRA can induce a proliferative response, resulting in a rapidly increasing peripheral white blood cell count (WBC) that can herald the retinoic acid syndrome that is characterized by features of capillary leak.15 This syndrome, which is not exclusively associated with an increasing WBC, can occur in up to 25% of APL cases and is associated with a high mortality unless energetically treated with steroids. Pre-emptive chemotherapy administered as the WBC increases also can abort the development of the syndrome.16

ATRA clearly has a crucial role to play in this disease, but the optimal means of combining ATRA and chemotherapy remains to be determined. In our experience, use of chemotherapy alone for this disease17 was associated with an overall survival of 54% at 5 years, but 13% of cases failed to achieve complete remission (CR) because of fatal hemorrhage. In this study, we sought to determine the relative benefit of using ATRA therapy for a 5-day period only before commencing chemotherapy with the aim of minimizing hemorrhagic deaths.6 This was compared with the coadministration of ATRA with chemotherapy, in which the aim was to achieve effective cytoreduction without exposing patients to the risk of developing the ATRA syndrome, which might occur if they were treated with ATRA alone. Knowledge of the molecular details of the fusion genes created by this translocation has opened the way to evaluate RT-PCR–based methods to confirm diagnosis and to evaluate response to treatment. In association with this trial, bone marrow samples were characterized at the molecular level to compare diagnostic precision with morphology and cytogenetics and during and after chemotherapy in an attempt to clarify the place of RT-PCR analysis in predicting relapse.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

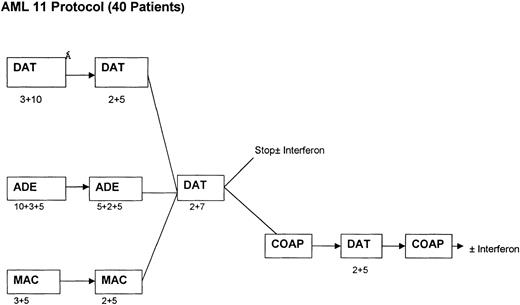

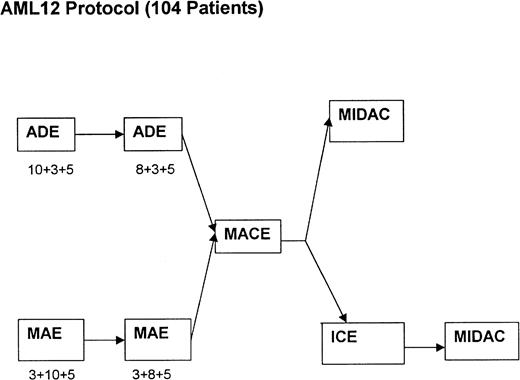

Between January 1993 and January 1997, 239 patients who were morphologically considered by the local physicians to have APL and who were entered into the current chemotherapy trials conducted by the MRC Leukaemia Working Parties were randomized to receive ATRA at 45 mg/m2/d either as a 5-day course before commencing chemotherapy (short ATRA) or to commence ATRA on the first day of chemotherapy and continue daily until CR or a maximum of 60 days (extended ATRA). For patients in the short ATRA arm in which an arbitrary WBC threshold of 25 × 109/L or greater was reached, it was recommended that chemotherapy should start immediately. The chemotherapy for patients less than 55 years of age was the MRC AML 10 protocol, which was subsequently superseded by MRC AML 12 for patients less than 60 years of age. Older patients were treated throughout on the MRC AML 11 protocol. The chemotherapy schedule for AML 10 has been described elsewhere17 and is summarized in Fig 1. In AML 12, patients were randomized to receive ADE or MAE (where Mitoxantrone was substituted) in the first 2 courses, followed by MACE and MidAc as in AML 10 with or without ICE (Idarubicin, Cytosine, Etoposide) as course 5. In AML 11, patients were randomized to receive DAT, MAE, or ADE for the first 2 courses, followed by DAT (2+7) with or without 3 further courses [COAP × 2, DAT (2+5)]. Patients in these three trials were eligible for randomization to receive granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) as supportive care after course 1. G-CSF treatment started on day +8 after the end of chemotherapy until recovery of neutrophils to 0.5 × 109/L. Thirteen patients in the MRC 10 trial received transplantation, but these were equally divided between the two arms: 6 short (4 allo and 2 auto) and 7 extended (3 allo and 4 auto). The date of last follow-up was August 1, 1998, when the median follow-up was 41 months.

Cytogenetic and Molecular Characterization

Cytogenetic analysis was performed in accordance with ISCN guidelines.18 Twenty metaphases were fully examined after at least 16 hours of culture to detect clonal abnormalities. For patients with a detectable clonal abnormality, at least 10 metaphases were examined to exclude additional changes, in accordance with the UK central quality control scheme guidelines (UK NEQAS-National External Quality Assessment Schemes). Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) studies using PML and RARα probes (VYSIS, IP) have been described elsewhere.19

RT-PCR.

To establish the frequency of PML/RARα rearrangements among patients with a clinical diagnosis of APL, to determine whether PMLbreakpoint is of any prognostic significance, and to evaluate the role of minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring in APL, nested RT-PCR was performed using primers to detect both PML-RARα andRARα-PML fusion transcripts, as fully described previously.20 Sensitivity assays for this method using the APL cell line NB4 (kindly provided by Michel Lanotte, Hôpital St Louis, Paris, France), which exhibits a bcr 1 PML breakpoint diluted in HL60 filler cells that are negative for thePML/RARα rearrangement, show that the PML-RARαassay can detect 1 APL cell in 104, whereas theRARα-PML assay is more sensitive, with a detection limit of 1 in 105.21 Identical sensitivities were also observed with serial dilutions of diagnostic bone marrow derived from a case with a bcr 3 PML breakpoint. For both diagnostic and MRD assays, a 1 in 1,000 dilution of NB4 was routinely included as a positive control together with an HL60-negative control and water controls for the RT and PCR steps. In all assays, normal RARα and PML transcripts were detected as controls for RNA integrity, as described previously.20-22 Negative results were only considered to be reliable with successful amplification ofRARα and PML RNA controls and provided that all other controls were satisfactory. All RT-PCR assays were performed at least twice, and results as determined by gel electrophoresis were routinely confirmed by hybridization with a junctional RARα cDNA probe (H7b).21

There are two major breakpoints within PML: 5′ (bcr 3) breakpoints typically occur within intron 3, whereas breakpoints in the 3′ region usually occur within intron 6 (bcr 1) and less commonly disrupt more proximal exonic sequence (bcr 2), most usually exon 6.20,23,24 In the present study, 5′ (bcr 3) and 3′ (bcr 1/2) PML breakpoints were distinguished on the basis of characteristic band sizes shown by nested RT-PCR.20 Bcr 1 and 2 3′ PML breakpoints were distinguished by a combination of RT-PCR using a PML exon 5 primer, PML/RARα junctional oligoprobe hybridization, and sequence analysis as detailed in full previously.20 In 1 patient, APL was associated with t(11;17)(q12-q21), leading to the detection of PLZF-RARα and RARα-PLZF fusion transcripts.25

PML immunofluorescence.

Where availability of suitable diagnostic material permitted, immunofluorescence studies were performed as previously described.20 A polyclonal PML antiserum was used in cases lacking molecular and cytogenetic evidence for the t(15;17) and also in a group with documented t(15;17) as positive controls.

Study Endpoints

CR was defined as a normocellular bone marrow aspirate which was usually performed 21 to 23 days from the end of allocated chemotherapy containing less than 5% blast cells and showing evidence of maturation in all lineages. Concurrent central morphological review of diagnostic material was provided and CR was confirmed by the treating physician. Remission failures were classified as early death (ED), induction death (ID; ie, related to treatment and/or hypoplasia), or resistant disease (RD; ie, failure to achieve CR and including partial remissions with 5% to 15% blasts). Where a clinician’s evaluation of response was not given, deaths within 10 days of study entry were classified as ED, deaths between 10 and 30 days as ID, and deaths beyond 30 days as RD. Overall survival (OS) is the time from randomization to death. Disease-free survival (DFS) is the time from first remission to first event (either relapse or death in CR). Relapse risk is the cumulative probability of relapse, censoring at death in CR.

Statistical Methods

Randomizations were undertaken by telephone to a central office in Oxford, UK. Minimization was used to ensure that approximately equal numbers of patients were allocated to each arm, both overall and within age group, type of AML (de novo/secondary), performance status, and induction treatment. Remission rates and reasons for failure were compared using the χ2 test. For other endpoints, Kaplan-Meier life-tables were constructed for each endpoint and were compared by means of the log-rank test, with surviving patients being censored at August 1, 1998 when follow-up was up to date for 97% of the patients. In addition to overall analyses, analyses were performed within potentially important prognostic risk groups, ie, age, WBC <10 or ≥10 × 109/L, additional cytogenetic changes, and 5′ or 3′ PML molecular breakpoints.

All P values are two-tailed. All point estimates quoted are at 3 years from randomization. All analyses are on the basis of intention to treat with all randomized patients analyzed in their allocated arm (short or extended ATRA) irrespective of whether they received the allocated treatment.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The characteristics of the 239 patients are shown in Table 1. During the course of this trial, some patients received G-CSF as supportive care from day +8 after the end of chemotherapy.26 These patients were evenly distributed between the arms.

Characteristics of Patients

| Characteristic . | Short (N = 119) . | Extended (n = 120) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | ||

| 0-14:15-29:30-39:40-49:50-59:60-69:70+ | 6:28:21:31:19:11:3 | 8:27:21:31:18:12:3 |

| Male/female | 61/58 | 59/61 |

| Performance score | ||

| 0:1:2:3:4 | 37:42:21:14:5 | 36:42:26:13:3 |

| De novo/secondary* | 113/6 | 111/9 |

| WBC ×109/L:0-9.9/10.0+/not known | 79/36/4 | 89/29/2 |

| Cytogenetics/molecular/diagnosis | ||

| t(15:17) alone | 59 | 58 |

| t(15:17) plus other | 34 | 36 |

| t(15:17) molecular | 14 | 15 |

| Chemotherapy protocol | ||

| AML 10/12:DAT/ADE/MAE | 25/49/25 | 24/52/24 |

| AML11: DAT/ADE/MAC | 4/5/11 | 3/5/12 |

| G-CSF/placebo | 19/23 | 24/24 |

| Characteristic . | Short (N = 119) . | Extended (n = 120) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | ||

| 0-14:15-29:30-39:40-49:50-59:60-69:70+ | 6:28:21:31:19:11:3 | 8:27:21:31:18:12:3 |

| Male/female | 61/58 | 59/61 |

| Performance score | ||

| 0:1:2:3:4 | 37:42:21:14:5 | 36:42:26:13:3 |

| De novo/secondary* | 113/6 | 111/9 |

| WBC ×109/L:0-9.9/10.0+/not known | 79/36/4 | 89/29/2 |

| Cytogenetics/molecular/diagnosis | ||

| t(15:17) alone | 59 | 58 |

| t(15:17) plus other | 34 | 36 |

| t(15:17) molecular | 14 | 15 |

| Chemotherapy protocol | ||

| AML 10/12:DAT/ADE/MAE | 25/49/25 | 24/52/24 |

| AML11: DAT/ADE/MAC | 4/5/11 | 3/5/12 |

| G-CSF/placebo | 19/23 | 24/24 |

Eleven patients had chemotherapy for prior malignancy; 4 had prior hematological disorders (3 MDS and 1 NHL).

Compliance with treatment.

Because of early death, 12 patients (7 short and 5 extended) did not receive ATRA. Of those allocated to extended ATRA, 88% received the drug on schedule, but 12% of patients violated the protocol by commencing ATRA treatment 1 to 3 days before the chemotherapy. Of those allocated to short ATRA, 64% started chemotherapy at day 5, 26% started before day 5 because of an increasing WBC of greater than 25 × 109/L (as prescribed in the protocol), and 10% started treatment before the 5-day course was completed due to protocol violation. All analysis was undertaken on an intent-to-treat basis.

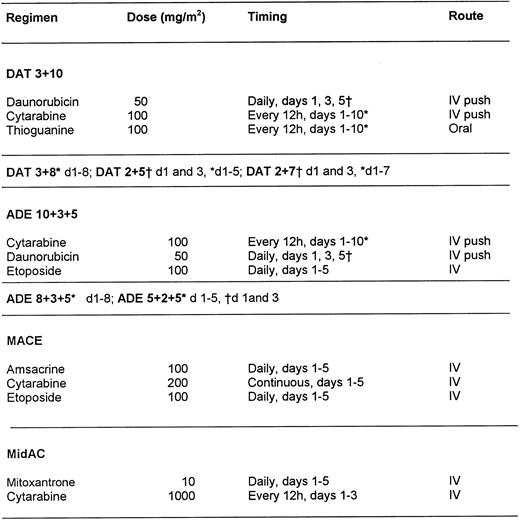

Cytogenetic and molecular characterization of disease.

Cytogenetic and molecular screening for PML/RARαrearrangements was routinely performed. The presence of the rearrangement was confirmed by cytogenetics and/or molecular analysis in 216 of 239 patients, as shown in Fig 2. In 187 of 216 patients, the t(15;17) was identified by conventional cytogenetics, whereas in 29 of 216 patients, the PML/RARαrearrangement was established by molecular techniques, including RT-PCR (n = 28) and FISH (n = 1). Cytogenetic analyses in this latter group were most commonly normal (n = 12) or failed (n = 11); in the remaining 6 patients, other clonal abnormalities were detected, of which 2 had chromosomes 15 and 17 of normal appearance. Among the 12 patients with normal karyotype and documented PML/RARαrearrangements, PML-RARα and RARα-PML fusion transcripts were both detected in 6, suggesting that the conventional t(15;17) had occurred, but had been missed despite culture of marrow cells for at least 16 hours before analysis. In the remaining 6 patients, PML-RARα was the sole fusion transcript detected consistent with insertion events, as we have recently demonstrated by further characterization of a series of such cases by FISH, including those derived from the MRC ATRA trial.25

PML immunofluorescence demonstrated the classic microparticulate nuclear staining indicative of the presence of the PML-RARαfusion protein in 14 of 14 patients with a documented t(15:17)20 25 and in 16 of 19 patients with crypticPML/RARα rearrangements. The absence of the microparticulate pattern in 3 cases was accounted for by technical failure (n = 1) or absence of leukemic cells in the peripheral blood (n = 2). In 21 of the entrants to the trial, no evidence was found for the existence of a PML/RARα rearrangement (Fig 2). In 7 cases, another primary cytogenetic abnormality was found; in 12 cases, RT-PCR, FISH, or a wild-type nuclear staining pattern on PML immunofluorescence failed to confirm cryptic rearrangements; and 2 cases were excluded on morphological review. In 1 patient in whom molecular methods failed, APL was confirmed by morphology review.

Response to Treatment

Remission induction.

The extended ATRA arm had a significantly higher rate of CR (87%v 70%, P ≤ .001), less resistant disease (2% v 7%, P = .03), and fewer early and induction deaths (12% v 23%, P = .02; Table 2). This difference was not influenced by the chemotherapy schedule administered, whether they received G-CSF or not, or by patient age, although there was an overall effect of age on CR rate. However, the level of WBC (>10 or <×109/L) was influential on treatment outcome.

Remission Induction

| . | Overall . | WBC <10 × 109/L . | WBC >10 × 109/L . | <60 yrs (n = 210) . | >60 yrs (n = 29) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | |

| Remission (%) | 70 | 87* | 76 | 94* | 61 | 66 | 72 | 89 | 50 | 73 |

| Early deaths (%) | 10 | 8 | 2.6 | 1 | 22 | 24 | 11 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| Induction deaths (%) | 13 | 4† | 9 | 2 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 43 | 7 |

| Resistant disease (%) | 7 | 2‡ | 12 | 3* | 3 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

| . | Overall . | WBC <10 × 109/L . | WBC >10 × 109/L . | <60 yrs (n = 210) . | >60 yrs (n = 29) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | |

| Remission (%) | 70 | 87* | 76 | 94* | 61 | 66 | 72 | 89 | 50 | 73 |

| Early deaths (%) | 10 | 8 | 2.6 | 1 | 22 | 24 | 11 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| Induction deaths (%) | 13 | 4† | 9 | 2 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 43 | 7 |

| Resistant disease (%) | 7 | 2‡ | 12 | 3* | 3 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

P < .001.

P < .02.

P < .03.

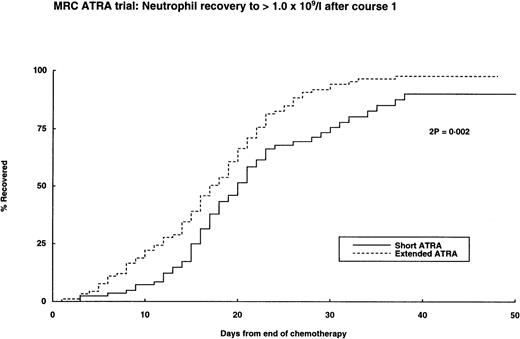

One hundred sixty-eight patients (70% of entrants) presented with a WBC of less than 10 × 109/L, of whom 143 (85%) entered CR, compared with 62% of those with a WBC greater than 10 × 109/L. Within this low count group, the extended ATRA arm resulted in a superior CR rate (94% v 76%) due to less deaths or resistant disease (Table 2), but no benefit was seen in patients in the higher WBC group. A possible explanation for the reduced induction deaths in the extended ATRA arm is the speed of hematopoietic regeneration from induction treatment, which was significantly more rapid for neutrophils and platelets in the extended arm (Fig 3). However, the early and induction deaths mostly occurred before they could be influenced by the count recovery. No such regeneration differences were noted in subsequent courses of chemotherapy. Confirmed or possible haemorrhagic deaths occurred in 10 patients and infection occurred in 5 patients. Four of 27 deaths in the short ATRA arm and 1 of the 14 deaths in the extended ATRA were attributed to the retinoic acid syndrome; there were 2 and 1 other deaths, respectively, with respiratory complications that were not recorded as RA syndrome. There were no important differences of response between the arms within the cytogenetic or molecular subgroups or in the 21 patients in whom APL was not confirmed.

Hematopoietic recovery after first course of chemotherapy.

Deaths in Remission

Of those in remission, 7 of 83 (8%) in the short ATRA arm and 7 of 104 (8%) in the extended ATRA arm died in CR during cytopenia after subsequent courses of chemotherapy, giving an actuarial risk of death of 10% at 4 years.

Relapse Risk

There were 42 relapses, including 3 in the central nervous system (CNS), 2 of whom presented with a low WBC. There was an overall significant reduction in relapse risk for those on the extended ATRA arm (20% v 36%, P = .04; Table 3); however, this benefit was most obvious in the low WBC group (13% v 35%, P = .04) and not in the high WBC group (47% v 36%, P = .5; Table3). There was no difference in this effect by age group or molecular/genetic subgroup. There was no significant difference between the arms in second remission rates (short 65% v extended 50%,P = .5) or survival at 2 years from relapse (short 44%v extended 43%, P = .5).

Outcome After CR

| Outcome at 4 yrs . | Overall . | WBC <10 × 109/L . | WBC >10 × 109/L . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | |

| Death in CR (%) | 8 | 8 (P = 1.0) | 8 | 8 (P = .9) | 9 | 0 (P = .8) |

| Relapse risk (%) | 36 | 20 (P = .04) | 35 | 13 (P = .04) | 36 | 47 (P = .5) |

| DFS (%) | 59 | 72 (P = .07) | 59 | 77 (P = .02) | 58 | 53 (P = .6) |

| Survival from relapse at 2 yrs (%) | 44 | 43 (P = .5) | Numbers too small | |||

| OS (%) | 52 | 71 (P = .005) | 57 | 80 (P = .0009) | 43 | 43 (P = .6) |

| Outcome at 4 yrs . | Overall . | WBC <10 × 109/L . | WBC >10 × 109/L . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | Short . | Extended . | |

| Death in CR (%) | 8 | 8 (P = 1.0) | 8 | 8 (P = .9) | 9 | 0 (P = .8) |

| Relapse risk (%) | 36 | 20 (P = .04) | 35 | 13 (P = .04) | 36 | 47 (P = .5) |

| DFS (%) | 59 | 72 (P = .07) | 59 | 77 (P = .02) | 58 | 53 (P = .6) |

| Survival from relapse at 2 yrs (%) | 44 | 43 (P = .5) | Numbers too small | |||

| OS (%) | 52 | 71 (P = .005) | 57 | 80 (P = .0009) | 43 | 43 (P = .6) |

DFS

The patients who entered CR in the extended arm had a significantly superior DFS compared with those on the short ATRA arm (72% v59%, P = .07), but this advantage was limited to the low count patients (77% v 59%, P = .02) and was not apparent in those with a presenting WBC greater than 10 × 109/L (53% v 58%, P = .6).

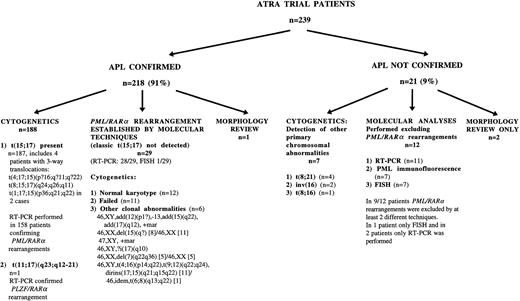

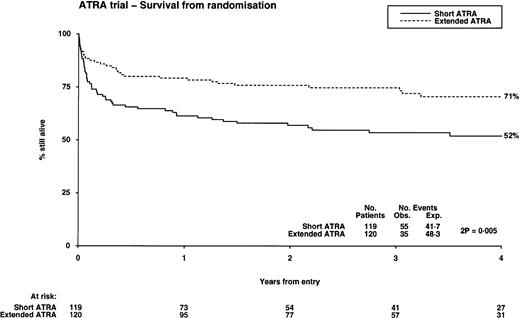

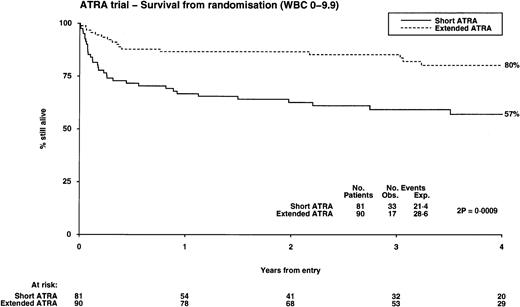

OS

The OS from diagnosis was significantly better in the extended ATRA arm, being 71% compared with 52% in the short ATRA arm (Table 3), but this benefit was also restricted to patients with a low WBC, where it was 80% in the extended arm versus 57% in the short arm (P = .0009; test for heterogeneity of effect, P = .003), but with no evidence of benefit in patients with a higher WBC (Fig 4). This benefit was apparent over all age groups and was unaffected by the presence of additional cytogenetic abnormalities; however, it is noteworthy that all 4 patients whose additional cytogenetic lesion was adverse in its own right (3 had 3q abnormalities, 1 complex) relapsed. The survival in the 21 patients who did not have APL was 57%, compared with the 40% achieved in the similar age cohort with chemotherapy alone in the MRC AML 10 trial.17 Within the MRC AML 10 protocol, 185 patients received the same chemotherapy as used in younger patients in this study before ATRA was introduced. The survival for these patients was 54% at 4 years, which is the same as the result achieved with short ATRA in this study. Thirteen patients were transplanted. They were evenly distributed between the arms, but censoring their follow-up at time of transplant did not affect the results presented here.

Overall survival from randomization: the influence of presenting white blood cell count.

Overall survival from randomization: the influence of presenting white blood cell count.

Influence of Molecular Characterization by RT-PCR

Molecular characterization was achieved in 202 of 239 patients who entered this trial, of whom 186 (92%) were confirmed to have thePML/RARα rearrangement. Of these, only 158 (85%) were identified by cytogenetics. No significant differences in outcome were seen between those confirmed cytogenetically (and molecularly) or the 28 cases confirmed molecularly only (CR, 78% v 81%; relapse risk, 25% v 8%; P = .1; OS, 63 v 82%;P = .09). Because the protocol permitted patients to enter the trial based on a morphological definition and 21 of the 239 entrants were subsequently shown not to have APL, the outcomes were analyzed separately. Of the 218 cases confirmed, 69% (short) and 86% (extended) achieved CR, compared with 73% and 90%, respectively, of the 21 non-APL cases. The respective DFS for confirmed cases at 4 years was 58% (short) and 74% (extended), compared with 63% (short) and 56% (extended) for the non-APL cases. With respect to OS at 4 years, the confirmed cases were 53% (short) and 73% (extended), compared with 44% (short) and 50% (extended) in the unconfirmed cases.

The nature of the breakpoint was characterized in 186 patients and was 5′ (bcr 3) in 72 (39%) and 3′ (bcr 1/2) in 114 (61%). This relative proportion did not significantly differ whether the t(15:17) was alone or was associated with other cytogenetic changes, with age, or with WBC. Bcr1 and 2 breakpoints were distinguished in 100 patients, showing 12 bcr2 cases. PML breakpoint position made no difference to initial response (bcr1/2, 82%; bcr3, 78%), but there was a nonsignificant trend for a lower relapse risk in 3′ breakpoints (19% v 42%), but this did not translate into a survival difference (bcr1/2, 67%; bcr3, 65%). ReciprocalRARα-PML transcripts were expressed in 142 of 186 patients (76%) but had no effect on survival. The patient with thePLZF/RARα rearrangement was treated with extended ATRA achieving CR after course one, as reported elsewhere.27

MRD Monitoring Studies

Molecular monitoring studies were performed on 105 patients with documented rearrangements to determine the kinetics of achievement of molecular remission after treatment. Detection rates ofPML-RARα and RARα-PML fusion transcripts in bone marrow samples taken after hematopoietic recovery after each course of chemotherapy are shown in Fig 5. In patients expressing RARα-PML, disappearance of these reciprocal derived transcripts was frequently found to lag behindPML-RARα, consistent with the increased sensitivity associated with the RARα-PML assay previously noted in dilution studies of the NB4 cell-line.21 28 Use of theRARα-PML assay in addition to the more conventional method for PML-RARα led to the detection of disease-related transcripts in an additional 20% (21/105) of patients while in morphologic CR and included 4 patients with 5′ PMLbreakpoints as well as 17 with 3′ breakpoints.

Kinetics of transcript response to chemotherapy. ()PML-RAR; (▩) PML-RARand/or RAR-PML.

Kinetics of transcript response to chemotherapy. ()PML-RAR; (▩) PML-RARand/or RAR-PML.

None of the 35 patients from whom bone marrow was examined after the fourth course of chemotherapy had detectable PML-RARαtranscripts; nevertheless, 11 of 35 ultimately relapsed. TheRARα-PML assay had been informative at diagnosis in 8 of the relapsing patients; however, reciprocal transcripts were undetectable in 7 of these 8 patients after completion of therapy (3′ PML breakpoint, n = 3; 5′ PMLbreakpoint, n = 4), despite the increased sensitivity associated with this method. Overall, 22 of 35 patients assessed at the end of treatment had an informative RARα-PML assay at diagnosis; reciprocal transcripts were detected in 2 of these patients immediately after completion of therapy: 1 patient with a 3′ PMLbreakpoint subsequently tested PCR-negative in a further sample received 24 months later with no intervening therapy and remains in complete continuous remission (CCR) at 3.5 years after completion of therapy, whereas the other patient with a 5′PML breakpoint relapsed within 7 months. Twelve patients found to express RARα-PML at diagnosis (3′ PMLbreakpoint, n = 9; 5′, n = 3) and maintaining long-term remission were also evaluated for both fusion transcripts in the first year after completion of therapy; none was found to be RT-PCR positive. No difference was observed in the rate of disappearance ofPML-RARα and/or RARα-PML transcripts between patients randomized to extended or short ATRA.

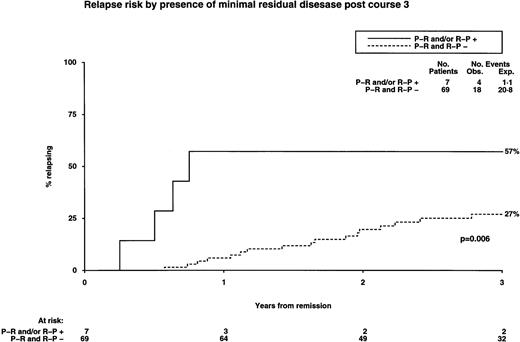

We then sought to determine whether there was a difference in RT-PCR profiles between 26 patients who ultimately relapsed and 79 remaining in CCR. The detection rate of disease-related transcripts after each course of chemotherapy was greater among the group who ultimately relapsed. Among the whole group, detection of transcripts at any stage after induction or during consolidation therapy was associated with an increased risk of relapse (Fig 6). This trend was found to be most predictively useful after the third course of chemotherapy, when most patients were evaluable, coinciding with the timing of bone marrow harvesting in the AML 10 and 12 trials. Detection of disease-related transcripts at this stage predicted a significantly increased risk of relapse (Fig 6) and poorer OS (57% v 89%,P = .02). Among 12 patients studied at relapse, no discrepancy was observed in either PML breakpoint or RARα-PMLexpression pattern in comparison to the time of initial presentation.

Influence of molecular (RT-PCR) status after chemotherapy on relapse.

DISCUSSION

It is now accepted that retinoic acid plays a key role in the treatment of APL. Although this subtype of AML has always tended to be more sensitive to chemotherapy alone, this study and other studies have shown that survival is significantly improved when chemotherapy is combined with retinoic acid.11-14,29 A 5-day schedule used before chemotherapy in the hope of reducing early deaths, particularly associated with coagulopathy, was clearly inferior to a continuous schedule of retinoid administered until CR was confirmed. Indeed, when a cohort of 50 patients treated with short ATRA on the MRC AML 10 protocol included here are compared with an historical group of 185 patients with APL in that trial receiving the same chemotherapy at an earlier stage of that trial without retinoid, no improvement in remission rate, DFS, or OS was observed. The benefit of extended retinoic acid was limited to the 70% of patients who presented with a low WBC. We were unable to show any benefit for patients presenting with a WBC greater than 10.0 × 109/L. This level was chosen because patients treated in our pre-ATRA schedules with a WBC greater than 10 × 109/L had a lower CR (70% v 87%) and a poorer 5-year survival (43%v 55%) than those with lower counts, but others have also shown that a WBC greater or less than 5 × 109/L is influential on outcome.8 We found on analysis of this study that there was little difference between using 5.0 or 10.0 as the appropriate cut-off. Although there was an increased risk of relapse in patients with a higher WBC who achieved CR, the main reason for the difference in outcome was an excess of early deaths, ie, within 30 days of diagnosis (27 v 14 events). In the extended arm of this trial, patients received ATRA until CR or day 60, whichever came first. In fact, the median duration was 28 days (range, 0 to 62 days), which for most patients was with course 1 only. Whether the addition of retinoid to consolidation treatment would reduce further the relapse risk is a potential question for prospective trials, although there are preliminary data that suggest that maintenance treatment with ATRA can reduce relapse risk.13

The retinoic acid syndrome has been reported in up to 25% of cases receiving ATRA alone.15 Because of the multi-institutional pattern of care in this trial (101 different institutions took part), we were anxious to minimize the risk of this complication in the study design either by limiting the period of exposure to ATRA as a single agent to 5 days (with the proviso that, if the WBC increased, chemotherapy would be initiated) or by starting the chemotherapy at the same time. On reviewing the early death reports, 4 of 27 deaths in the short ATRA were ATRA syndrome, with an additional 2 respiratory deaths not so labeled. Only 1 ATRA syndrome and 1 respiratory death were reported in the extended ATRA arm. Whether prophylactic steroids would be beneficial in patients who present with a high count as a means of circumventing this problem is not clear.30

We have previously demonstrated that there is nothing to be gained in undertaking a transplant procedure in first remission in good cytogenetic risk cases.31,32 The small number of transplanted patients, who were equally divided between the arms, did not influence the trial result in that the results did not change if they were censored at time of transplant. The policy of delaying transplant beyond CR1 becomes even clearer now in low count cases of APL who receive extended ATRA treatment. For reasons that are not entirely clear, a relatively modest increase in WBC makes a major impact on outcome that is not changed by the use of extended ATRA, although the number of such patients who entered CR was small. Once in CR, these patients have a 41% risk of an event (36% of relapse), but it would be statistically difficult to show a benefit of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in this subgroup, because the procedure itself carries a 15% to 20% risk, and even after relapse there is a survival of 25% in this group. An autograft should have a lower procedural risk, and we know from the results of our MRC AML 10 trial32 in the APL subgroup that it can reduce the risk of relapse (25% v 49%). The Italian experience suggests that the success of autograft depends on the patient being RT-PCR negative at the time of transplant.33

Because retinoic acid is such an important component in the treatment of APL, it is crucial that all useful techniques are deployed to identify patients who will benefit. It has previously been shown that the PML/RARα rearrangement characterizes such patients.9 In this study, we have demonstrated that, for a number of reasons (mostly technical failure), cytogenetics alone was not optimal. It is of interest that 21 patients who entered this study and received retinoid were subsequently shown not to have APL. When these patients are excluded, the survival at 4 years is 73% for extended versus 53% for short. Although RT-PCR is the most valuable, not least because it defines targets for minimal residual disease detection, it is helpful to use FISH and PML immunofluorescence, as we have demonstrated. Only 85% of patients were identified by conventional cytogenetics. Those positive by RT-PCR alone have a similar survival, and it is therefore reasonable to accept this as a basis on which to make clinic decisions, as already indicated by others.14 The breakpoint frequency observed in our study is similar to that in other recently published series,14,34but we have not been able to find a relationship between breakpoint and additional cytogenetic abnormalities as reported in a previous smaller study.35 Whether PML breakpoint influences outcome is a somewhat contentious issue,22,34,36,37 probably reflecting relatively small sample sizes and interstudy and intrastudy treatment variation. Our study is in accordance with the results reported from Memorial Sloan Kettering,36 suggesting that the presence of a 5′ (bcr 3) PML breakpoint is associated with an increased risk of relapse. In both studies, the increased risk of relapse was at a borderline level of significance; indeed, in the present study, there was no difference in overall survival. This would suggest that there are insufficient data at present to justify the use of PML breakpoint pattern as a means of directing treatment approach in individual patients. Indeed, other groups have observed no difference in outcome according to PMLbreakpoint,34 37 suggesting that any such effect may reflect therapeutic differences between the studies or the play of chance.

Finally, we sought to determine whether molecular monitoring could provide independent prognostic information in patients treated with ATRA and chemotherapy. Recent studies have demonstrated that monitoring for PML-RARα fusion transcripts postconsolidation can predict subsequent relapses as well as outcome after autologous bone marrow transplantation performed in second morphological CR.33,38 Early studies also suggested that PCR status after completion of therapy was of key prognostic significance and stressed the importance of achievement of molecular remission as a prerequisite for long-term survival, although persistent PCR positivity was found to predict a poor prognosis.9,10 However, these early studies included significant numbers of patients treated with ATRA as single-agent therapy or individuals treated in relapse, in whom, in retrospect, a high frequency of persistent PCR positivity associated with a poor long-term prognosis was not unexpected. It is now clear that combinations of ATRA and chemotherapy constitute the optimal treatment approach for APL at present and, as shown in this study and others, the majority of patients treated in this way ultimately achieve molecular remission.14,21 However, recent studies demonstrate that molecular monitoring strategies in which PCR status is only determined immediately postconsolidation fails to predict relapse in the majority of patients who ultimately do so.14,21,38This phenomenon reflects the relative insensitivity of conventionalPML-RARα assays, although this lack of sensitivity belies its highly predictive nature when MRD detection is performed regularly postconsolidation.38 Given the increased sensitivity of theRARα-PML assay, we sought to determine whether additional use of this assay could more successfully detect residual disease in patients who ultimately relapsed. However, RARα-PMLtranscripts were detected in only 1 of the 8 informative relapsing patients tested after completion of therapy, suggesting that this assay also lacks sufficient sensitivity using conventional methods to detect residual disease in all patients who eventually relapse. However, attempts to further increase sensitivity using conventional assays have failed to achieve more clinically useful prognostic information, serving merely to identify disease-related transcripts in a series of patients in long-term remission.28 39

The advantage of the present study is the demonstration that molecular monitoring during the treatment period can provide independent prognostic information in the context of a relatively homogeneous disease. This would suggest that newer technologies such as real time PCR,40 which affords the opportunity to quantify disease-related transcripts relative to an internal control, may more accurately establish subgroups of patients at particular risk of relapse during consolidation therapy, who may benefit from more intensive consolidation therapy, including transplantation procedures.

It remains to be established whether a policy of treatment of molecular relapse is more advantageous than delaying intervention to the time of clinical relapse. Preliminary data suggest that it is. The majority of patients examined during consolidation in our study were molecularly negative. Although such patients are at a lower risk of relapse, because they are the majority, the absolute number of relapses is larger in this group. Such patients may be best served by regular monitoring after consolidation as a means of predicting impending relapse, but this would require at least 3 monthly review marrows. Even then, not all patients can be treated at the time when there is solely molecular evidence of disease, due to false-negative PCR results reflecting poor sample quality or rapid hematological relapses not predicted by the preceding PCR result. For this reason, it may be pragmatic for the smaller group of APL patients with delayed clearance of disease-related transcripts in consolidation to be treated with more intensive consolidation therapy. Given the improved prognosis of APL patients treated with extended ATRA and chemotherapy, the resolution of these important issues will require clinical trials, including even greater numbers of patients, necessitating collaboration of intranational and international study groups.

APPENDIX

Contributors.

A.K.B. was involved in trial design and trial coordination and wrote the report. D.G. undertook the molecular studies and wrote the report. E.S. supervised the molecular studies. K.W. was involved in trial design, supervised the data collection, and undertook statistical analysis and finalization of the report. A.H.G. was involved in study design and trial coordination.

Trial participants.

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (N.B. Bennett, D.J. Culligan, A.A. Dawson); Addenbrooke’s Hospital (R. Marcus); Alder Hey Children’s Hospital (M. Caswell); Belfast City Hospital (Z.R. Desai, T.C.M. Morris); Birmingham Heartlands Hospital (D.W. Milligan); Bradford Royal Infirmary (L.A. Parapia, A.T. Williams); Bristol Royal Infirmary (G.L. Scott); Cheltenham General Hospital (R.G. Dalton); Christchurch Hospital (D.N.J. Hart); City Hospital NHS Trust (D. Bareford); Conquest Hospital (J. Beard, S.G. Weston-Smith); Derbyshire Royal Infirmary (A. McKernan, D.C. Mitchell); Derriford Hospital (A. Prentice); Dundee Teaching Hospital NHS Trust (P. Cachia); Ealing Hospital (U.M. Hegde); Eastbourne District General (R.J. Grace); Falkirk & Dist. Royal Infirmary (A.D.J. Birch); Frimley Park Hospital (J. VanDePette); George Eliot Hospital (M.N. Narayanan); Glan Clwyd District General Hospital (D.R. Edwards); Gloucester Royal Hospital (J. Ropner); Grantham District NHS Trust (V.M. Tringham); Great Ormond Street Hospital (J.M. Chessells, I.M. Hann); Guy’s Hospital (S.A. Schey); Halifax General Hospital (A.J. Steed); Hammersmith Hospital (J. Apperley, J.M. Goldman); Harrogate General Hospital (M.W. McEvoy); Hillingdon Hospital (R. Jan-Mohamed); Hinchingbrooke Hospital (C.E. Hoggarth); Horton General Hospital, NHS Trust (I.J. Durrant); Hospital for Sick Children, Bristol (A. Oakhill); Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh (A. Thomas); Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow (E. Chalmers, B. Gibson); Huddersfield Royal Infirmary (C. Carter); Ipswich Hospital (C.N. Simpson); King’s College Hospital (G. Mufti); King’s Mill Hospital (E. Logan); Kingston General Hospital (M.L. Shields); Law Hospital (T.L. Allan); Leeds General Infirmary (J.A. Child, D.R. Norfolk, G.M. Smith); Leicester Royal Infirmary (C.S. Chapman, R.M. Hutchinson, J.K. Wood); Lincoln County Hospital (M.A. Adelman); Lister Hospital (S.M. Watkins); Manor Hospital (G.P. Galvin); Monklands District General (E.J. Fitzsimons, W. Watson); Norfolk & Norwich Hospital (A.J. Black, J. Leslie); North Staffs Hospital Centre (P.M. Chipping, R.M. Ibbotson); Northampton General Hospital (J.R.Y. Ross, S.S. Swart); Nottingham City Hospital (N.H. Russell); Oxford Radcliffe Hospital (P. Emerson, T.J. Littlewood, J.S. Wainscoat); Pembury Hospital (D.S. Gillett); Peterborough District Hospital (S.A. Fairham, M. Sivakumuran, J.A. Wimperis); Pilgrim Hospital (S. Sobolewski); Prince Philip Hospital (R.V. Majer); Queen Alexandra Hospital (T. Cranfield, M. Ganczakowski); Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham (J.A. Holmes); Queen Mary’s Sidcup NHS Trust (S. Bowcock); Raigmore Hospital (C.J. Lush); Royal Chesterfield Hospital (R. Collin); Royal Cornwall Hospital, Treliske (M.D. Creagh, A.R. Kruger); Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital (M.V. Joyner); Royal Hallamshire Hospital (J.T. Reilly, D.A. Winfield); Royal Hants. County Hospital (W.O. Mavor); Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (A.C. Parker); Royal Liverpool University Hospital (J.C. Cawley, R.E. Clark); Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital (R.F. Stevens); Royal Marsden Hospital (S.T. Meller); Royal Shrewsbury Hospital (N. O’Connor), Royal Sussex County Hospital (J. Duncan); Royal United Hospital NHS Trust (C.R.J. Singer); Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast (F.G.C. Jones, E.E. Mayne); Sandwell General Hospital (S.I. Handa, P.J. Stableforth); Scunthorpe General Hospital (S. Jalihal); Selly Oak Hospital (J.A. Murray, W.N. Patten); Sheffield Children’s Hospital (J.S. Lilleyman); Southampton University Hospital Trust (A. Duncombe, A.G. Smith); Southmead Hospital (R.R. Slade); St George’s Hospital (D.H. Bevan); St. James’s University Hospital (D.L. Barnard, B.A. McVerry); St Thomas’ Hospital (R. Carr); Staffordshire General Hospital (P. Revell); Stirling Royal Infirmary (D.M. Ramsay); Stobhill General Hospital (R.B. Hogg); Taunton & Somerset Hospital (M.J. Phillips); The North Hampshire Hospital (A.E. Milne); UCL Medical School, London (D.C. Linch); University College Hospital, Galway (E.L. Egan); University College Hospital, London (S. Devereux, A. Goldstone, K.G. Patterson); University Hospital of Wales (A.K. Burnett, S.H. Lim, C. Poynton, J.A. Whittaker); Victoria Infirmary (P.J. Tansey); Warwick Hospital (P.E. Rose); West Suffolk Hospital (P. Harper); Western General Hospital (P. Ganly); Western General Hospital (M.J. Mackie); Western Infirmary (N.P. Lucie); Whipps Cross Hospital (C. DeSilva); Whiston Hospital (J. Tappin); William Harvey Hospital (D.G. Wells); Worcester Royal Infirmary (A.H. Sawers, R. Stockley); Worthing Hospital (A.W.W. Roques); Wycombe General Hospital (S. Kelly); York District Hospital (L.R. Bond); Ysbyty Gwynedd (H.E.T. Korn, D.H. Parry).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The Working Party is grateful to Dr Graham Fothergill and Roche Pharmaceutical for providing ATRA for this trial. We thank the clinicians who entered their patients into this trial; Dr David Swirsky and Sameena Iqbal for performing FISH studies; Steve Langabeer for handling trial samples; Helen Walker for supervising cytogenetic reporting and the regional cytogeneticists; Georgina Harrison for data retrieval; Siân Edwards for preparing the manuscript; and Dr Francesco Lo Coco for constructive review of the manuscript.

D.G. was supported by an MRC Clinical Training Fellowship and by ICRF and is currently supported by the Leukaemia Research Fund. E.S. was supported by EEC Grants No. BIOMED-CR92-0755 and Biotech BI02-CT-930450. Molecular studies for the ATRA trial were supported by the MRC and ICRF. Material for molecular analyses was derived from the MRC AML Trial Tissue bank at University College Hospital, which is supported by the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Alan K. Burnett, MD, Department of Haematology, University of Wales College of Medicine, Heath Park, Cardiff CF4 4XN, UK; e-mail: BurnettAK@Cardiff.ac.UK.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal