Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) typically afflicts elderly patients with a median age of 65 years. However, while recently shown to provide superior outcome to standard treatment, high-dose therapy (HDT) has usually been limited to patients up to 65 years. Among 550 patients with MM and a minimum follow-up of 18 months, 49 aged ≥65 years were identified (median age, 67; range, 65 to 76 years). Their outcome was compared with 49 younger pair mates (median, 52; range, 37 to 64 years) selected among the remaining 501 younger patients (<65 years) matched for five previously recognized critical prognostic factors (cytogenetics, β2-microglobulin, C-reactive protein, albumin, creatinine). Nearly one half had been treated for more than 1 year with standard therapy and about one third had refractory MM. All patients received high-dose melphalan-based therapy; 76% of the younger and 65% of the older group completed a second transplant (P = .3). Sufficient peripheral blood stem cells to support two HDT cycles (CD34 > 5 × 106/kg) were available in 83% of younger and 73% of older patients (P = .2). After HDT, hematopoietic recovery to critical levels of granulocytes (>500/μL) and of platelets (>50,000/μL) proceeded at comparable rates among younger and older subjects with both first and second HDT. The frequency of extramedullary toxicities was comparable. Treatment-related mortality with the first HDT cycle was 2% in younger and 8% among older subjects, whereas no mortality was encountered with the second transplant procedure. Comparing younger/older subjects, median durations of event-free and overall survival were 2.8/1.5 years (P = .2) and 4.8/3.3 years (P = .4). Multivariate analysis showed pretransplant cytogenetics and β2-microglobulin levels as critical prognostic features for both event-free and overall survival, whereas age was insignificant for both endpoints (P = .2/.8). Thus, age is not a biologically adverse parameter for patients with MM receiving high-dose melphalan-based therapy with peripheral blood stem cell support and, hence, should not constitute an exclusion criterion for participation in what appears to be superior therapy for symptomatic MM.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA (MM) afflicts approximately 13,000 Americans annually. Symptom manifestations relate to anemia, osteopenia and lytic bone disease, hypercalcemia, renal failure, and immunodifficiency.1,2 Over one half of the patients are older than 65 years at diagnosis. After lack of progress with standard-dose therapy over three decades,2hematopoietic stem cell supported high-dose therapy (HDT) has become the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients, especially younger individuals who are thought to be able to withstand the potentially greater toxicity incurred with myeloablative regimens.3-5Fortunately, treatment-related mortality has decreased to 5% or less, mainly as a result of rapid hematopoietic engraftment with the use of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) collected early in the disease course and mobilized with hematopoeitic growth factors alone or in conjunction with chemotherapy.6

Since the introduction of autotransplants for MM,7,8 our patients were eligible for HDT up to age 70. In recent years, we essentially discontinued an upper age limit when disease severity was judged to outweigh the anticipated toxicities from HDT. In extensive analyses of both newly diagnosed and previously treated patients, age did not factor in as an adverse feature for event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS).9 Instead, prognosis was dominantly impacted by cytogenetics, β2-microglobulin (B2M), and C-reactive protein (CRP) as well as duration of prior therapy.10 11

Prompted by health insurance considerations for patients 65 years and older, we examined patients’ outcome after autotransplant-supported HDT in relationship to age. This report compares our experience with HDT in 49 patients ≥65 years and 49 younger patients, after matching for prognostically relevant pretreatment features.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between December 1989 and August 1997, 900 patients were enrolled in tandem autologous transplant trials using melphalan 200 mg/m2 (MEL200) for the first cycle.9 A second HDT cycle was usually administered within 3 to 6 months consisting of MEL200 in case partial response (PR) was sustained. Patients with less than PR status were offered combination therapy (MEL140 + total body irradiation [TBI] 850 to 1125 cGy) or MEL200 and added high-dose cyclophosphamide (HDCTX; usually 6 g/m2); the latter regimen was used when patients were deemed not to be candidates for a TBI-containing regimen because of prior local radiation. All PBSC were collected before both autotransplants, either with HDCTX plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or granulocyte macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) or with G-CSF alone as reported previously.12 13

Forty-nine patients aged ≥65 years were identified who had a minimum posttransplant follow-up of 18 months. During this time interval, 501 younger patients (<65 years) were also treated. Using a standardized Euclidian distance measure,14 49 pair mates were identified whose prognostically relevant disease, host, and treatment features were comparable (Table 1). Pair mates were established using the following pretransplant prognostic factors: B2M, albumin, creatinine, CRP, and the presence or absence of unfavorable chromosomal abnormalities (11q breakpoints, monosomy 13 or deletion 13q, and any translocation).10 11

Comparability of Prognostic Features Among Young and Old Patients

| Favorable Parameter . | % Patients . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 yr (N = 49) . | 65-69 yr (N = 39) . | ≥70 yr (N = 10) . | ||

| Cytogenetics | 74 | 64 | 90 | .2 |

| B2M ≤2.5 mg/L | 51 | 33 | 40 | .2 |

| CRP ≤4.0 mg/L | 53 | 38 | 60 | .3 |

| ≤12 mo of prior therapy | 55 | 54 | 70 | .6 |

| Non-IgA isotype | 82 | 85 | 70 | .6 |

| Sensitive | 59 | 64 | 70 | .8 |

| LDH ≤190 U/L | 88 | 92 | 80 | .5 |

| Stage <III | 49 | 58 | 60 | .6 |

| Albumin >3.5 g/dL | 51 | 46 | 40 | .8 |

| Creatinine ≤2 mg/dL | 96 | 95 | 100 | .8 |

| Second transplant | 76 | 69 | 50 | .3 |

| CD34 >5 × 106/kg | 83 | 72 | 80 | .4 |

| Favorable Parameter . | % Patients . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 yr (N = 49) . | 65-69 yr (N = 39) . | ≥70 yr (N = 10) . | ||

| Cytogenetics | 74 | 64 | 90 | .2 |

| B2M ≤2.5 mg/L | 51 | 33 | 40 | .2 |

| CRP ≤4.0 mg/L | 53 | 38 | 60 | .3 |

| ≤12 mo of prior therapy | 55 | 54 | 70 | .6 |

| Non-IgA isotype | 82 | 85 | 70 | .6 |

| Sensitive | 59 | 64 | 70 | .8 |

| LDH ≤190 U/L | 88 | 92 | 80 | .5 |

| Stage <III | 49 | 58 | 60 | .6 |

| Albumin >3.5 g/dL | 51 | 46 | 40 | .8 |

| Creatinine ≤2 mg/dL | 96 | 95 | 100 | .8 |

| Second transplant | 76 | 69 | 50 | .3 |

| CD34 >5 × 106/kg | 83 | 72 | 80 | .4 |

All patients had to sign an informed consent indicating the potential benefit and toxicities associated with the tandem autotransplant programs. Protocols and consent forms had been reviewed and approved by the institutional review board and, where appropriate, by the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration. Clinical endpoints considered treatment-related mortality (TRM) within 60 days of HDT, separately for first and second autotransplant. Additionally, TRM was computed 6 and 12 months after the first HDT cycle. Complete response (CR) was defined as the absence, on immunofixation analysis of serum and urine, of monoclonal protein in the presence of normal morphologic examination of bone marrow aspirate and biopsy with less than 1% of tumor cells identified on the basis of DNA-cytoplasmic immunoglobulin flow cytometric analysis.15 CR had to be documented on at least two occasions at a minimum time interval of 3 months. EFS and OS were computed from the first HDT cycle. CR duration was measured from the first onset of CR to disease relapse or death. In addition, hematopoietic recovery was determined using threshold levels for granulocytes of at least 500/μL and of platelets of at least 50,000/μL, both with first and second transplant. Grade III and IV extramedullary toxicities were also determined.

Statistical methods used chi-squared tests for comparison of patient characteristics, the Kaplan-Meier product limit method for estimation of survival,16 and the log-rank test for comparison for CR duration, EFS, and OS.17 Multivariate analysis was used to determine the prognostically independent variables associated with various clinical endpoints.18

RESULTS

The median age in the younger group ranged from 37 to 64 years (median, 52 years) and from 65 to 76 years (median, 67 years; 70 years, 7 patients; 71 years, 1; 72 years, 1; 76 years, 1 patient) among the older patients (P = .0001). Patient characteristics were well matched for the main risk factors previously identified to affect EFS and OS after autotransplants10 11 (Table 1). Specifically, the incidence of favorable cytogenetics (absence of aberrations of chromosomes 11 and 13 as well as any translocation) was similar in young patients and in the two older cohorts. Fifty-five percent to 70% had ≥12 months of prior therapy. Fewer older patients presented with low B2M ≤2.5 mg/L (P = .2). The proportion of patients with high CD34 counts (>5 × 106/kg) was similar (P = .4). A second transplant was applied in 76% of patients <65 years, 69% in the 65 to 69 years group, and in 50% of those ≥70 years. As far as regimens were concerned, all patients received MEL200 with the first autograft. The second transplant consisted of MEL200 in 18 of 37 (49%) among those <65 years, 11 of 27 (41%) in the middle age group, and in 4 of 5 (80%) in the old age group. MEL140 + TBI/MEL-HDCTX/other regimens were applied in 8/5/6 patients <65 years; and 12/2/2 of those aged 65 to 69 years and 1/0/0 in the ≥70-year group.

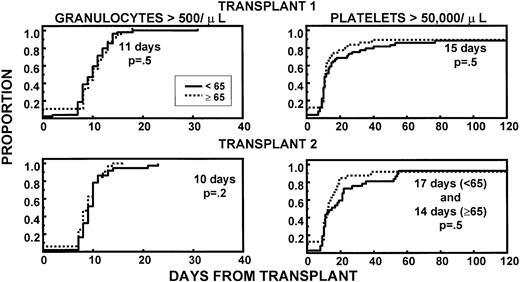

Granulocyte and platelet recoveries were superimposable in both age groups, after first and second HDT cycle, indicating excellent PBSC quantities and function (Fig 1). The frequencies of extramedullary toxicities were similar in younger and older patients during both transplant procedures (Table2). TRM within 60 days of the first transplant was 2% in younger (intracranial hemorrhage, 1 patient) and 8% in older patients (death of unknown cause after complete hematopoietic recovery, 66 years; pneumonia, 69 years; intracranial hemorrhage subsequent to trauma, 70 years; sepsis caused by delayed engraftment after CD34-selected autograft, 70 years) (P = .2). None of the second transplant recipients in either age group experienced TRM.

Similar recovery kinetics of granulocytes (>500/μL) and of platelets (>50,000/μL) in young and old patients, with both first and second transplant. The fraction of patients with CD34 >5 × 106/kg was comparable between age groups.

Similar recovery kinetics of granulocytes (>500/μL) and of platelets (>50,000/μL) in young and old patients, with both first and second transplant. The fraction of patients with CD34 >5 × 106/kg was comparable between age groups.

Grade >III Nonhematologic Toxicities

| Toxicity . | 1st Transplant . | P . | 2nd Transplant . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 yr (N = 49) . | ≥65 yr (N = 49) . | <65 yr (N = 37) . | ≥65 yr (N = 32) . | |||

| Mucositis/diarrhea | 20* | 31 | .2 | 19 | 34 | .1 |

| Pneumonia/sepsis | 24 | 12 | .2 | 19 | 9 | .3 |

| Early deaths | 2 | 8 | .2 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Toxicity . | 1st Transplant . | P . | 2nd Transplant . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 yr (N = 49) . | ≥65 yr (N = 49) . | <65 yr (N = 37) . | ≥65 yr (N = 32) . | |||

| Mucositis/diarrhea | 20* | 31 | .2 | 19 | 34 | .1 |

| Pneumonia/sepsis | 24 | 12 | .2 | 19 | 9 | .3 |

| Early deaths | 2 | 8 | .2 | 0 | 0 | — |

Percent of patients.

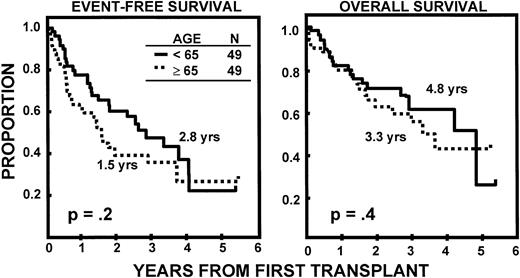

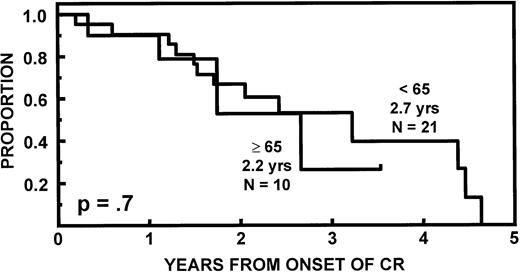

The incidence of CR was lower in older than in younger subjects (20v 43%, P = .02). EFS and OS durations were comparable (Fig 2) as were CR durations (Fig 3). Multivariate analysis of pretransplant prognostic variables among all 98 patients identified favorable cytogenetics and low B2M as good risk features for both EFS and OS; in addition, months of prior therapy was also important for EFS. However, age was not a significant risk factor for either EFS or OS once these variables were accounted for (Table3).

Similar durations of EFS and OS after autotransplant-supported HDT in patients <65 and ≥65 years.

Similar durations of EFS and OS after autotransplant-supported HDT in patients <65 and ≥65 years.

Age Not Important for Clinical Outcome on Multivariate Analysis

| EFS . | P . | OS . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable cytogenetics | .004 | Favorable cytogenetics | .009 |

| ≤12 mo prior therapy | .01 | B2M ≤2.5 mg/L | .03 |

| B2M ≤2.5 mg/L | .01 | ≤12 mo prior therapy | .4 |

| Age <65 yr | .2 | Age <65 yr | .8 |

| EFS . | P . | OS . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable cytogenetics | .004 | Favorable cytogenetics | .009 |

| ≤12 mo prior therapy | .01 | B2M ≤2.5 mg/L | .03 |

| B2M ≤2.5 mg/L | .01 | ≤12 mo prior therapy | .4 |

| Age <65 yr | .2 | Age <65 yr | .8 |

DISCUSSION

This report confirms our previous experience that age per se does not affect outcome after autotransplant for MM, whether examined as a continuous or categorical variable. This finding may be due, in large part, to the availability of adequate quantities of CD34+cells in young and old patients, assuring comparable durations of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia and, thus, minimizing the risk of infection and other toxicities. A cumulative injury from a second HDT cycle to either the bone marrow micro-environment or other critical organs was not apparent in either age group. We confirm, in both young and old patients, the importance of cytogenetics and B2M as key variables for sustained disease control. On the basis of our results, there is no biological justification for an age-discriminant policy for MM therapy. In fact, the incidence and nature of complex chromosomal aberrations did not differ among young and old, although different pathogenetic mechanisms may still be revealed at the molecular level.

Palumbo et al recently reported on the safety and efficacy of sequential HDT regimens with cyclophosphamide and melphalan (“CM” regimen)19 as well as repeated sub-myeloablative doses of MEL100 with PBSC support.20 In preparation for regular inclusion of older subjects in HDT trials, we are currently evaluating tandem autotransplants in patients 70 years and older, using MEL140 with the first HDT cycle and, depending on tolerance and antitumor effect, MEL140 or MEL200 with the second transplant. There are no exclusions according to renal function (which we have shown not to affect MEL clearance).21 We conclude that optimal therapy for MM with PBSC-supported high-dose melphalan therapy should not be withheld from the majority of older patients presenting with MM who deserve optimal control of their disease and, thereby, gaining hopefully many years of high-quality life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors greatly acknowledge the dedicated services of the nursing staff, the confidence of many referring physicians who have entrusted us with their patients’ medical care, and to Caran Hammonds for excellent secretarial assistance.

Supported in part by Grant No. CA55819 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to B. Barlogie, MD, PhD, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W Markham Slot 776, Little Rock, AR 72205.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal