Abstract

In vitro studies have provided little consensus on the kinetic abnormality underlying the myeloid expansion of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Transplantation of human CML cells into non-obese diabetic mice with severe immunodeficiency disease (NOD/SCID mice) may therefore be a useful model. A CML cell line (BV173) and peripheral blood cells collected from CML patients in chronic phase (CP), accelerated phase (AP), or blastic phase (BP) were injected into preirradiated NOD/SCID mice. Animals were killed at serial intervals; cell suspensions and/or tissue sections from different organs were studied by immunohistochemistry and/or flow cytometry using antihuman CD45 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs), and by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the BCR-ABL fusion gene. One hour after injection, cells were sequestered in the lungs and liver, but 2 weeks later they were no longer detectable in either site. Similar short-term kinetics were observed using51Cr-labeled cells. The first signs of engraftment for BV173, AP, and BP cells were detected in the bone marrow (BM) at 4 weeks. At 8 weeks the median percentages of human cells in murine marrow were 4% (range, 1 to 9) for CP, 11% (range, 5 to 36) for AP, 38.5% (range, 18 to 79) for BP, and 54% (range, 31 to 69) for BV173. CP cells progressively infiltrated BM (21%) and spleen (6%) by 18 to 20 weeks; no animals injected with the cell line or BP cells survived beyond 12 weeks. The rate of increase in human cell numbers was higher for BP (7.3%/week) as compared with CP (0.9%/week) and AP (0.5%/week). FISH analysis with BCR and ABL probes showed that some of the human cells engrafting after injection of CP cells lacked a BCR-ABL gene and were presumably normal. We conclude that CML cells proliferate in NOD/SCID mice with kinetics that recapitulate the phase of the donor’s disease, thus providing an in vivo model of CML biology.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

CHRONIC MYELOGENOUS leukemia (CML) is a neoplastic disorder originating in a primitive hematopoietic stem cell. After a chronic phase (CP) of variable length, CML eventually progresses to an accelerated phase (AP) and later to a blastic phase (BP) that results in the patient’s death. The kinetic abnormality underlying the myeloid expansion in CML has not been fully clarified. Although there is evidence of an increased self-renewal ability of CML progenitors,1,2 long-term culture-initiating cells from CML patients show a very poor self-maintenance capacity.3 One reason for these apparently discordant results might be that studies have been limited to the use of in vitro culture assays using clinical samples (reviewed in Gordon and Goldman4). Moreover, results from such in vitro studies may not be relevant for the identification of the proliferative cell fraction5 or the quantification of the proliferation rate in CML patients.6 Therefore, an in vivo model of CML that recapitulates the kinetics of the different disease phases is highly desirable.

Various types of inbred immune-deficient mice have been used in efforts to produce a suitable host for xenografts of human hematopoietic tissue (reviewed in Uckun7). The introduction of the severe combined immunodeficient mouse crossed with the non-obese diabetic strain (NOD/SCID) has provided a powerful tool to support growth in vivo of human hematopoietic cells and thus to characterize neoplastic hematopoiesis.8,9 This model has been used to titrate primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells,9,10 to identify the target cell for leukemic transformation,11 and to model the natural history of some solid tumors.12 It can also be used to test various in vivo therapeutic strategies, already reported using cell lines13-15 and to assess the efficiency of gene therapy.9 16

The SCID mouse supports growth of CML cells and CML cell lines to a variable degree.14 17 Cells from advanced disease may grow well, but engraftment with CP cells has hitherto only been detected by molecular analysis. The kinetics of engraftment, which provide the essential baseline for therapeutic testing, have not yet been investigated. In this study NOD/SCID mice were injected with a CML cell line and hematopoietic cells from CML patients at different disease stages. To assess the kinetics of engraftment, we monitored the cells soon after injection and weekly thereafter by staining with human CD45 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for BCR-ABL, and morphologic examination of tissue sections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NOD/SCID mice.

NOD/SCID mice (initially obtained from Dr John Dick, Toronto, Canada) were bred and maintained in a pathogen-free environment at the Institute of Child Health animal facility. Before inoculation of cells, 6- to 8-week old mice were irradiated with 300 to 325 cGy from137Cs radiation source.

Cells were infused into the tail vein in a volume of 0.3 mL sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). No cytokines were used. Mice were killed at different intervals after injection unless they became ill earlier. Blood was taken by intracardiac puncture from anesthetized mice. At autopsy, spleen, liver, bone marrow (BM), lungs, kidneys, lymph nodes, and brain were removed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for subsequent histologic preparations (BM was decalcified in 10% formalin/5% formic acid). Half of the spleen and the BM from one femur was homogenized to obtain cell suspensions for immunophenotypic analysis and FISH studies.

Preparation of cells for injection.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected from patients with CML at different disease stages and used in different experiments. Patients gave informed consent for these studies. Twelve patients were in CP, four patients in AP, and four patients in BP. The disease phase was defined according to standard criteria. The features of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Features of the Patients at the Time of Sampling

| Patient No. . | Disease Status . | Treatment Received-150 . | Time From Diagnosis (months) . | Additional Cytogenetic Abnormalities . | WCC (×109/L) . | % of Blasts in BM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | 1st CP | None | 2 | None | 134 | 3 |

| CP2 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 326 | 1 |

| CP3 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 86 | 1 |

| CP4 | 1st CP | None | 2 | None | 289 | 1 |

| CP5 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 297 | 2 |

| CP6 | 2nd CP-151 | allo-BMT | 22 | t(10;14)(p11;q11), del(13)(q) | 85 | 2 |

| CP7 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 238 | 1 |

| CP8 | 1st CP | None | <1 | t(9;22;12)(q34;q11;q24) | 227 | 0.5 |

| CP9 | 1st CP | IFN | 5 | dup(4), del(12)(q15) | 72 | 2 |

| CP10 | 2nd CP-151 | allo-BMT | <1 | None | 568 | 5 |

| CP11 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 192 | 1 |

| CP12 | 1st CP | None | <1 | t(3;9;22)(q21;q34;q11) | 152 | 4 |

| AP1 | AP-151 | allo-BMT | 30 | several clonal/nonclonal changes | 132 | 10 |

| AP2 | AP | HU | None | 38 | 15 | |

| AP3 | AP | None | <1 | t(9;22;14)(q34;q11;q32) | 5 | 10 |

| AP4 | AP-151 | allo-BMT | 38 | NA | 42 | 9 |

| BP1 | M-BP-151 | allo-BMT | 26 | several clonal/nonclonal changes | 16 | 32 |

| BP2 | M-BP-151 | allo-BMT | 89 | +Ph | 71 | 50 |

| BP3 | M-BP-151 | allo-BMT | 50 | None | 77 | 31 |

| BP4 | M-BP | HU | 23 | None | 70 | 47 |

| Patient No. . | Disease Status . | Treatment Received-150 . | Time From Diagnosis (months) . | Additional Cytogenetic Abnormalities . | WCC (×109/L) . | % of Blasts in BM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | 1st CP | None | 2 | None | 134 | 3 |

| CP2 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 326 | 1 |

| CP3 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 86 | 1 |

| CP4 | 1st CP | None | 2 | None | 289 | 1 |

| CP5 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 297 | 2 |

| CP6 | 2nd CP-151 | allo-BMT | 22 | t(10;14)(p11;q11), del(13)(q) | 85 | 2 |

| CP7 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 238 | 1 |

| CP8 | 1st CP | None | <1 | t(9;22;12)(q34;q11;q24) | 227 | 0.5 |

| CP9 | 1st CP | IFN | 5 | dup(4), del(12)(q15) | 72 | 2 |

| CP10 | 2nd CP-151 | allo-BMT | <1 | None | 568 | 5 |

| CP11 | 1st CP | None | <1 | None | 192 | 1 |

| CP12 | 1st CP | None | <1 | t(3;9;22)(q21;q34;q11) | 152 | 4 |

| AP1 | AP-151 | allo-BMT | 30 | several clonal/nonclonal changes | 132 | 10 |

| AP2 | AP | HU | None | 38 | 15 | |

| AP3 | AP | None | <1 | t(9;22;14)(q34;q11;q32) | 5 | 10 |

| AP4 | AP-151 | allo-BMT | 38 | NA | 42 | 9 |

| BP1 | M-BP-151 | allo-BMT | 26 | several clonal/nonclonal changes | 16 | 32 |

| BP2 | M-BP-151 | allo-BMT | 89 | +Ph | 71 | 50 |

| BP3 | M-BP-151 | allo-BMT | 50 | None | 77 | 31 |

| BP4 | M-BP | HU | 23 | None | 70 | 47 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Treatment received at the time of sample harvesting for injection (HU, hydroxyurea; IFN, interferon-α).

Relapse post-allo–BMT.

For CD34+ cell purification, PBMC were labeled with immunomagnetic particle-coupled CD34 antibody (Qbend 10) and isolated using miniMacs (Miltenyi Biotec, Camberley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CD34 purity was >95%. CD34+ PBMC were injected at 5 × 106 cells per mouse. In some cases cells were cryopreserved and stored before use. Cryopreserved cells were thawed in the presence of DNAse type II (Sigma, St Louis, MO) to avoid clumps. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue before injection and if it was less than 90%, the viable cells were recovered by Ficoll centrifugation.

BV173, a lymphoid blast crisis CML cell line,18 was maintained in vitro in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 200 mmol/L L-glutamine, 10 U/mL penicillin, 50 mg/mL streptomycin, 25 mmol/L HEPES, and 10% fetal calf serum. Aliquots of 3 × 106cells were injected into each mouse.

In vivo tracking of radiolabeled cells.

Three million 51Cr-labeled BV173 or CML CD34+cells were injected intravenously (IV) into four NOD/SCID mice per group. After 1 hour, mice were killed and different organs removed. Each organ was placed in a tube and its radioactivity measured with a gamma counter. Radioactivity content was expressed by subtracting from Experimental CPM a percentage calculated from the ratio (Spontaneous release/Maximum release) × 100. Spontaneous and maximum release was determined on the supernatants of 3 × 10651Cr-labeled cells used for injection incubated in medium or Triton-X, respectively. For spontaneous release, cells were incubated in culture medium from the time of inoculum to the time of organ assessment.

Immunophenotypic analysis.

Mouse blood cells and cell suspensions from spleen and BM were analyzed for surface marker expression. Red blood cells were lysed with lysis buffer (Becton-Dickinson, UK Ltd, Oxford, UK) before staining. To assess human engraftment, cells were double-stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled mouse CD45 (clone I3/2) (Sigma Immunochemicals, Poole, UK) and phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled human CD45 (clone BRA55) (Sigma Immunochemicals) MoAbs. Relevant FITC- and PE-conjugated Ig class antibodies were used as controls. Cells were analyzed with a Becton-Dickinson flow cytometer. Positivity was also scored by fluorescence microscopy in samples with <2% human cells; at least 400 cells per sample were assessed. We compared accuracy and sensitivity of flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy by mixing human and mouse cells in defined proportions (human/mouse ratios of 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 50%). Percentages of human cells ≤5% were reliably detectable only at fluorescence microscopy and were comparable also to the figures detected by FISH analysis (data not shown).

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were assessed by histologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Morphologic examination was performed using conventional hematoxylin-eosin and Giemsa staining. Immunohistochemistry was performed with a human CD45 MoAb (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) using peroxidase-conjugated second layer antibody; conjugated second antibody alone served as a negative control. To characterize engraftment in selected cases, lineage-specific markers were studied: CD34 for progenitor cells, CD68 KP-1, and neutrophil elastase for myeloid cells, CD15 and CD68 PG-M1 for monocytes, CD79a and CD20 (B-Ly1) for B cells, CD45RO (UCHL1) for T cells, VS38c for plasma cells, and glycophorin C (Ret40) for red blood cells. All of the antibodies were purchased from Dako.

FISH.

FISH analysis was performed as previously described.19Briefly, cytospin preparations of BM cells from sacrificed mice were fixed in acetone and probed using a mixture of BCR sequences labeled with SpectrumGreen and ABL sequences labeled with SpectrumOrange (Vysis, Woodcreek, IL). The mixture was denatured at 73°C for 5 minutes and added immediately to the slides on a slide warmer at 45°C to 50°C. After washing, cells were stained with DAPI and mounted using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The probes discriminate mouse cells, normal human cells, and CML cells: mouse cells do not show any signal, normal human cells exhibit four separate dots, whereas leukemic cells show a fusion signal as a result of Ph chromosomal translocation, as well as two dots corresponding to the normal BCR and ABL genes. At least 100 human cells per slide were scored.

Quantification of in vivo cell growth.

The percentage of human cells was plotted against time after cell injection. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated by the Trapezium rule. The AUC provides a means to quantify the production of human hematopoietic cells in the NOD/SCID recipients.

RESULTS

Destiny of injected cells.

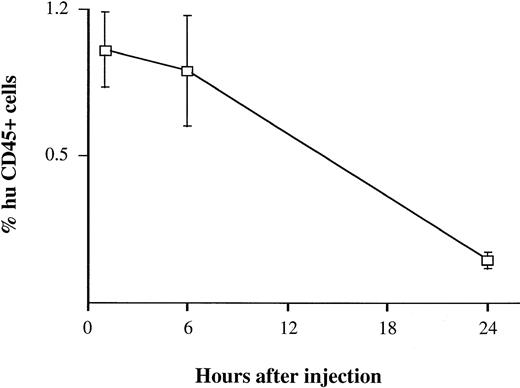

BV173 cells were injected into the tail vein at a dose of 3 × 106 cells. Assuming that the normal leukocyte count of a NOD/SCID mouse is 1 to 3 × 106/mL (data not shown) and its blood volume is about 2 mL, one would have expected to see approximately 50% of the cells in the mouse blood to have been of human origin if all of the injected cells remained in the circulation. Four mice were bled 1, 6, and 24 hours after injection. After 1 hour, only 1% (range, 0 to 1.5) of mouse blood cells analyzed by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy were human and at 24 hours, no human cells were detectable (Fig 1). Similar results were obtained using CD34+ cells isolated from peripheral blood of CML patients and healthy subjects (data not shown).

Detection of human cells in mouse blood soon after injection. BV173 cells were injected in the tail vein at a dose expected to give 50% of human cells in mouse blood. Mice were bled 1, 6, and 24 hours after injection. Quantification of human cells was assessed by staining with human CD45 MoAbs. Bars refer to standard deviations (SD). The same findings were observed using peripheral blood CD34+ cells from CML patients and healthy subjects.

Detection of human cells in mouse blood soon after injection. BV173 cells were injected in the tail vein at a dose expected to give 50% of human cells in mouse blood. Mice were bled 1, 6, and 24 hours after injection. Quantification of human cells was assessed by staining with human CD45 MoAbs. Bars refer to standard deviations (SD). The same findings were observed using peripheral blood CD34+ cells from CML patients and healthy subjects.

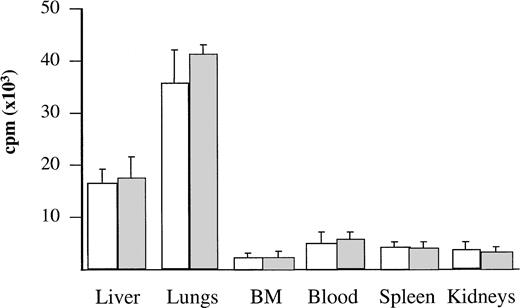

To assess the anatomical distribution of the cells, BV173 and CD34+ CML cells were labeled with 51Cr and injected into three mice per group. After 1 hour, mice were killed and different tissues were measured for radioactivity. The majority of the labeled cells were found in the lungs and liver: these organs contained 78% to 79% of the total radioactivity detected in the tissues examined. No significant levels of radioactivity were detected in the other tissues (Fig 2).

Localization of radiolabeled cells after injection. BV173 or CD34+ CML cells were labeled with 51Cr before injection. After 1 hour, mice were killed and different tissues were measured for radioactivity. Bars refer to SD. Radioactivity content was expressed as reported in Materials and Methods. (□) BV173 cells. (▧) CD34+ CML cells.

Localization of radiolabeled cells after injection. BV173 or CD34+ CML cells were labeled with 51Cr before injection. After 1 hour, mice were killed and different tissues were measured for radioactivity. Bars refer to SD. Radioactivity content was expressed as reported in Materials and Methods. (□) BV173 cells. (▧) CD34+ CML cells.

Kinetics of engraftment of BV173 cell line.

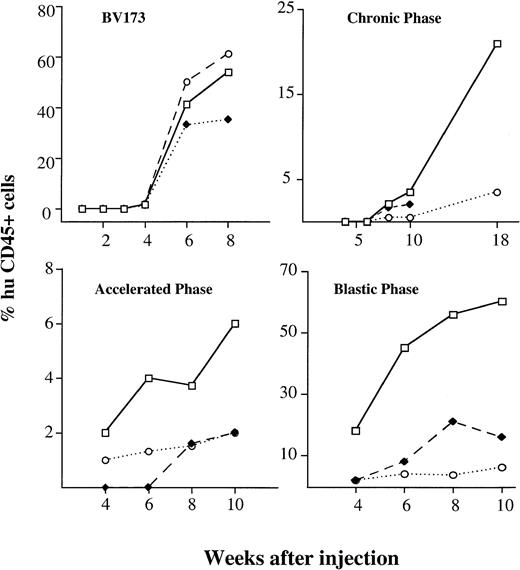

The kinetics and extent of engraftment were evaluated in mice killed at serial intervals (four mice per time point) after injection. Immunophenotypic analysis of cell suspensions from blood, BM, and spleen was performed by double staining with human and mouse CD45. Histologic sections of lungs, liver, kidney, lymph nodes, and brain were also investigated for secondary involvement. The first signs of engraftment of BV173 cells were detectable by immunophenotypic analysis at 4 weeks and engraftment progressively increased over the following 4 weeks. At 8 weeks, infiltration reached high median levels in the BM (54%), spleen (61%), and blood (35%) (Fig 3). Levels of engraftment were reproducible in all of the mice injected: the range was 31% to 69% in BM, 30% to 81% for spleen, and 11% to 47% in blood. Engrafting cells were all Ph-positive by FISH analysis.

Kinetics of engraftment CML cell line and hematopoietic cells from different disease stages. Kinetics of engraftment were assessed at serial intervals after injection. Values show the median percentages of human cells in different tissues (□———□ BM, ⧫– – –⧫ blood, ○·····○ spleen) detected by human CD45 staining on four mice killed at each time point. BV173 cell line and samples from four patients in CP (CP1, CP2, CP4, CP5), two in AP (AP1, AP2), and two in BP (BP1, BP2) were injected.

Kinetics of engraftment CML cell line and hematopoietic cells from different disease stages. Kinetics of engraftment were assessed at serial intervals after injection. Values show the median percentages of human cells in different tissues (□———□ BM, ⧫– – –⧫ blood, ○·····○ spleen) detected by human CD45 staining on four mice killed at each time point. BV173 cell line and samples from four patients in CP (CP1, CP2, CP4, CP5), two in AP (AP1, AP2), and two in BP (BP1, BP2) were injected.

Morphologic examination of tissue sections, performed in association with immunohistochemical staining with human CD45 MoAb, showed diffuse infiltration of BM and spleen by BV173. The liver was involved within sinusoids and peripheral areas, and the kidneys were involved as interstitial nodules. BV173 cells were never observed in lymph nodes and brain. Lung involvement, although detected 1 week after injection, was not seen thereafter.

Engraftment of CML hematopoietic cells.

The kinetics and extent of engraftment of hematopoietic cells from patients in different phases of CML was evaluated by injecting CD34-purified PBMC. Cells from 12 different patients in CP, four in AP, and four in BP were used.

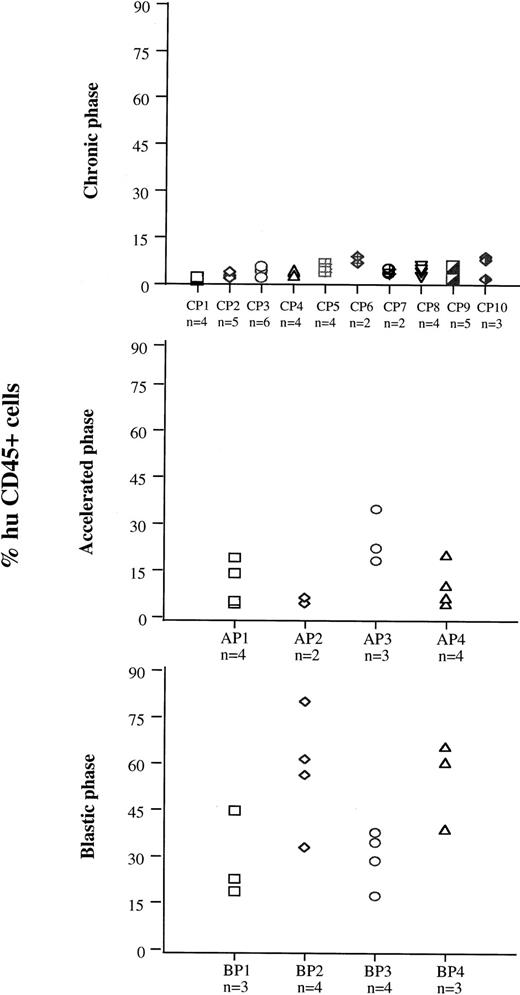

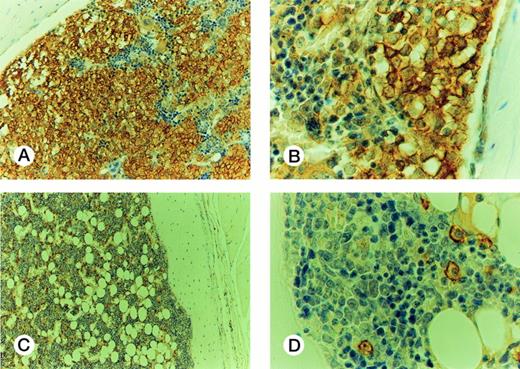

On the basis of the results obtained with cell lines, 7 to 8 weeks after injection was the time chosen to evaluate samples from patients at different disease stages for their ability to engraft mouse BM (Fig 4). Cells from 10 patients in CP (CP nos. 1 to 10), four in AP (AP nos. 1 to 4), and four in BP (BP nos. 1 to 4) were used for this purpose. Each sample was injected into groups of two to six irradiated mice. The median proportion of human CD45+ cells in murine BM was 4% (range, 1 to 9.1) for CP, 11% (range, 5 to 36) for AP, and 38.5% (range, 18 to 79) for BP. The rate of successful engraftment (≥1%) for CP cells was 85%. The difference in engraftment was significant between CP and AP (P< .0001, Mann-Whitney test), and between AP and BP (P < .0001). The extent of involvement of marrow by cells from BP was similar to that observed with BV173 cells, but extramedullary involvement was less extensive. Morphologically, the BP engrafted cells had the appearance of large blasts and were present in large clusters and sheets in the BM (Fig 5A and B). There was no evidence of differentiation towards mature hematopoietic elements. In contrast, human CD45+ CP and AP engrafted cells had the appearance of bland mononuclear cells, not blasts, and were evenly dispersed interstitially in the BM (Fig 5C and D).

BM engraftment of cells from different disease phases at 7 to 8 weeks. Cells from 10 patients in CP (CP 1 to 10), four in AP (AP 1 to 4), and four in BP (BP 1 to 4) were injected into groups of two to six preirradiated mice. Seven to 8 weeks after injection, mice were killed and the numbers of human CD45+ cells were assessed in BM cell suspensions.

BM engraftment of cells from different disease phases at 7 to 8 weeks. Cells from 10 patients in CP (CP 1 to 10), four in AP (AP 1 to 4), and four in BP (BP 1 to 4) were injected into groups of two to six preirradiated mice. Seven to 8 weeks after injection, mice were killed and the numbers of human CD45+ cells were assessed in BM cell suspensions.

Histology of murine BM engrafted with CML cells. Engraftment with BP cells: (A) The marrow is infiltrated by sheets of huCD45+ cells, with some residual huCD45-negative maturing hematopoietic elements; (B) The infiltrating cells are large, nucleolated blasts with strong surface immunoreactivity for huCD45. The smaller maturing erythoid elements are negative. Murine BM engrafted with CP cells: (C) the marrow contains frequent dispersed huCD45+ cells, comprising about 10% of the cellularity. The remaining huCD45-negative marrow elements appear normal. (D) The huCD45+ cells are medium sized mononuclear cells with round to oval nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm. They are dissimilar from the blasts seen in (B).

Histology of murine BM engrafted with CML cells. Engraftment with BP cells: (A) The marrow is infiltrated by sheets of huCD45+ cells, with some residual huCD45-negative maturing hematopoietic elements; (B) The infiltrating cells are large, nucleolated blasts with strong surface immunoreactivity for huCD45. The smaller maturing erythoid elements are negative. Murine BM engrafted with CP cells: (C) the marrow contains frequent dispersed huCD45+ cells, comprising about 10% of the cellularity. The remaining huCD45-negative marrow elements appear normal. (D) The huCD45+ cells are medium sized mononuclear cells with round to oval nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm. They are dissimilar from the blasts seen in (B).

The kinetics of engraftment were assessed at serial time intervals after the same procedure outlined for the cell line. Samples from four patients in CP, two in AP, and two in BP were injected. Three to four mice were used for each data point for each patient sample. The time to detection of the first signs of engraftment in BM reflected the nature of the sample used (Fig 3): whereas BP and AP cells were detectable at 4 weeks (median BM infiltration 18%; range, 12 to 23 and 2% range, 0 to 5, respectively), CP cells were not seen until 8 weeks (2.5%; range, 0.8% to 3%). At 10 weeks, a median level of 3.5% (range, 1% to 5%) human cells could be demonstrated with CP cells, 6% (range, 3% to 11%) with AP cells, and 59% (range, 39% to 65%) with BP cells. BM was the main tissue involved. However, while CP and AP cells were barely detectable in peripheral blood and spleen, BP cells also significantly infiltrated the spleen (18%; range, 10% to 25% at 10 weeks) and were found in the peripheral blood (5.4%; range, 1% to 7% at 10 weeks). None of the mice injected with BP cells survived for longer than 12 weeks and death coincided with massive leukemic infiltration in the BM. Three groups of four mice injected with three different samples of CP cells were killed at 18 to 20 weeks: a significantly higher (P < .0001) proportion of human cells was detected in BM (21%; range, 5% to 45%), and a significant proportion (P < .0001) was also found in the spleen (6%; range, 1% to 14%). One group of mice also had massive involvement of the liver (60%).

The results of the kinetic studies were analyzed by a method designed to express engraftment and the leukemic growth rate in numerical terms (Table 2). The AUC was used to plot the percent of human cells against time after transplant and to define the degree of engraftment in arbitrary units: the AUC value was 7.6 for CP cells, 27.4 for AP cells, and 308 for BP cells. The AUC value for BP was similar to that calculated for BV173 cells, ie, 266. Considering the increase in cell numbers as function of time, the growth increment for BP cells was 7.2% per week, for AP cells 0.5%, and for CP cells 0.9%.

Mathematical Analysis of the Kinetics of Engraftment

| Disease Phase . | AUC* . | Increment† . |

|---|---|---|

| CP | 7.6 | 0.9 |

| AP | 27.4 | 0.5 |

| BP | 308 | 7.2 |

| Disease Phase . | AUC* . | Increment† . |

|---|---|---|

| CP | 7.6 | 0.9 |

| AP | 27.4 | 0.5 |

| BP | 308 | 7.2 |

*AUC, Area under the curve (see Materials and Methods).

Increment is the percentage of increase in human cell numbers detected in mouse BM per week.

CP cells engrafting at 18 weeks were further characterized by immunohistochemical analysis with different antihuman MoAbs. All of the cells expressed the pan-myeloid marker CD68 (KP-1), but lacked CD68 (PG-M1), CD15, and neutrophil elastase. No progenitor cells were identified as assessed by CD34 staining, although we cannot exclude their presence in a number sufficient to assure regeneration, but undetectable by our staining technique. Only in one case were clusters of erythroid cells (glycophorin C-positive) observed, but no other hematopoietic lineages were detectable by CD45RO (T cells), CD20 and CD79a (B cells), and VS38c (plasma cells) MoAbs.

Engraftment at 8 weeks was also assessed in 17 mice (injected with nine different samples) by FISH analysis for the content of Ph-positive cells. The probes used did not hybridize with mouse cells, thus permitting scoring both normal (separate dots) and leukemic (fusion signal) human engraftment (see Materials and Methods). Table 3 shows the percentages of leukemic cells found in the human engraftment after 8 weeks from injection of different samples. The BM in three of six groups of mice (CP2, CP6, CP10) injected with CP cells contained an appreciable proportion of Ph-negative human cells (range, 15% to 29.4%). Two mice from each group of mice that were killed at 18 weeks were studied by FISH. In all of them human infiltration was 100% Ph-positive (data not shown). None of the BM samples derived from mice injected with AP or BP cells showed any Ph-negative cells. In the mice injected with cells from one patient (AP3), engrafting cells exhibited two copies of the BCR-ABL fusion gene; only one copy was detected in the sample at the time of injection.

Proportion of Leukemic Cells in the Engrafted Marrow

| Patient* . | Disease Stage . | Engraftment (%)† . | % of Ph-Positive Cells in the Graft‡ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| huCD45 . | FISH . | |||

| CP2 | CP | 4 | 7 | 85 |

| 4.1 | 4.8 | 94 | ||

| CP3 | CP | 4 | 5.8 | 100 |

| CP5/a | CP | 3.8 | 3 | 100 |

| CP5/b | 6.5 | 6 | 100 | |

| CP5/c | 4.8 | 4 | 100 | |

| CP5/d | 4 | 5 | 100 | |

| CP6 | CP | 10 | 9.1 | 70.6 |

| CP8 | CP | 2.3 | 3 | 100 |

| 4.1 | 5 | 100 | ||

| 5 | 5 | 100 | ||

| CP10 | CP | 7 | 7.7 | 77 |

| AP1 | AP | 18 | 22 | 100 |

| AP3/a | AP | 36 | 31 | 100 |

| AP3/b | 20 | 19 | 100 | |

| BP4/a | BP | 34 | 30 | 100 |

| BP4/b | 49 | 45 | 100 | |

| Patient* . | Disease Stage . | Engraftment (%)† . | % of Ph-Positive Cells in the Graft‡ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| huCD45 . | FISH . | |||

| CP2 | CP | 4 | 7 | 85 |

| 4.1 | 4.8 | 94 | ||

| CP3 | CP | 4 | 5.8 | 100 |

| CP5/a | CP | 3.8 | 3 | 100 |

| CP5/b | 6.5 | 6 | 100 | |

| CP5/c | 4.8 | 4 | 100 | |

| CP5/d | 4 | 5 | 100 | |

| CP6 | CP | 10 | 9.1 | 70.6 |

| CP8 | CP | 2.3 | 3 | 100 |

| 4.1 | 5 | 100 | ||

| 5 | 5 | 100 | ||

| CP10 | CP | 7 | 7.7 | 77 |

| AP1 | AP | 18 | 22 | 100 |

| AP3/a | AP | 36 | 31 | 100 |

| AP3/b | 20 | 19 | 100 | |

| BP4/a | BP | 34 | 30 | 100 |

| BP4/b | 49 | 45 | 100 | |

*Patient identification numbers refer to those reported in Table1. Letters a to d refer to the number of mice injected with the same sample.

Percentage of human cells in mouse BM detected by staining with human CD45 MoAbs. FISH results refer to the percentage of BCR and ABL (normal) and BCR-ABL (leukemic) positive cells in the mouse BM.

Percentage of leukemic (BCR-ABL-positive) cells in the graft (human cells) obtained after injection of cells from the different patients as detected by FISH analysis.

DISCUSSION

The kinetics and pattern of engraftment of CML cells in NOD/SCID mice were evaluated in this study. The BV173 cell line, a CML lymphoid blast crisis cell line, was used to establish the kinetics of engraftment from the time of cell injection to animal death and to provide a reproducible model for subsequent comparison with patients’ cells. Tracking of human cells by staining with human anti-CD45 MoAbs (Fig 1) or by radiolabeling (Fig 2) demonstrated that BV173 cells injected into NOD/SCID mice were rapidly cleared from the circulation and sequestered by the lungs and liver. At 1 week, lung sequestration was still evident, but by 2 weeks, no human cells were detected in any of the tissues examined. After 4 weeks, massive leukemic infiltration was seen in the BM, spleen, and peripheral blood and this led invariably to the death of animals within 12 weeks of injection (Fig 3).

On the basis of these data, the extent of engraftment in BM by patients’ CML cells was assessed after 7 to 8 weeks. The extent of engraftment significantly correlated with disease phase (Fig 4): BP cells engrafted better than AP cells (median values for tumor cells in murine marrow = 38.5% v 11%, P < .0001), and AP cells engrafted better than CP cells (median = 11% v 4%,P < .0001). Although BP cells have been previously reported to engraft efficiently in SCID mice,14,17,20 the limited success and the variability in CP cell engraftment have prevented a reliable comparison of cells from the different disease phases. Our data show that NOD/SCID mice are efficient recipients of human CML cells and that the extent of engraftment may be a useful read-out to characterize the course of the disease. This conclusion is supported by the analysis of engrafted cells by FISH with BCR and ABL probes (Table 3). Engraftment obtained with two of three samples from CP patients exhibited a proportion of Ph-negative progenitors (range, 15% to 29.4%). No normal human cells were detected in the mouse BM engrafted with the AP and BP samples. This disparity between cells from CP and cells from more advanced phases of CML is probably a genuine finding, because with the probes we have used, the false-negative rate never exceeds 10%.21 Our results differ from those reported by Sirard et al,17 who showed the majority (70%) of the human progenitors found in the engrafted BM were normal. This discrepancy might be explained by at least two major technical differences: (1) in Sirard’s study, the cell source for analysis was human hematopoietic colonies derived from CML-engrafted mouse BM rather than whole BM cells, ie, a selected population; and (2) Sirard et al used cytogenetic analysis of metaphase cells to detect the chromosomal rearrangement rather than FISH on interphase cells. Furthermore, the genetic background of the two different mouse strains may play some role in the selection of engrafting cells. In accord with our results is the relatively low proportion of normal progenitors detectable in fresh clinical samples.19,22,23

Although the extent of engraftment can give a good indication of disease stage, the question whether leukemic growth recapitulates the kinetics of chronic and blastic phase has not been addressed before. We demonstrate here that the kinetics of NOD/SCID mouse BM repopulation are different for CP, AP, and BP cells (Fig 3). Using BP cells, the first signs of engraftment were detected early (at 4 weeks) and within 12 weeks, all of the engrafted mice were dead. In contrast, human cells from CP patients were first detected only after 8 weeks; thereafter a slow, but progressive, increase in extent of BM involvement was observed reaching a level of 21% at 18 to 20 weeks. AP cells engrafted early, but the growth rate did not differ from that of CP cells. In general, differences in the kinetics and extent of engraftment were more evident when we analyzed the AUC and the increment in the leukemic growth rates. Thus, engraftment, as defined by the AUC value, was 40-fold higher with BP cells than with CP cells. The increment in the cell growth rate should be a more specific measure of BM repopulation kinetics, but it does not necessarily correlate with the extent of engraftment. In practice, this increment was significantly higher with BP than with CP cells (7.3%/week v 0.9%/week). However, while AP cells showed a higher AUC than CP cells, the growth increment was similar to that of CP cells. To this extent, the AUC may differentiate AP from CP better than the increment in growth rate, but further studies are warranted.

This study describes a system for propagating CML hematopoietic cells and quantitating their growth rate. Our results demonstrate that the time required for first signs of engraftment and the growth rate can be used to classify disease phase (Table 4). We conclude that the use of NOD/SCID mice is the best available in vivo model for investigating the kinetic abnormality underlying the myeloid expansion in CML and for testing potential therapeutic strategies.

Pattern of Engraftment in NOD/SCID Mice According to Phase of Patient’s CML

| Disease Phase . | Early Engraftment (<8 weeks) . | Rapid Proliferation* . |

|---|---|---|

| CP | No | No |

| AP | Yes | No |

| BP | Yes | Yes |

| Disease Phase . | Early Engraftment (<8 weeks) . | Rapid Proliferation* . |

|---|---|---|

| CP | No | No |

| AP | Yes | No |

| BP | Yes | Yes |

*Rapid proliferation is assessed by the increment of cell growth (no ≤ 2, yes > 2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Francis Grand and Andrew Chase who helped with FISH studies, to Claudia Giacon and William Batchelor for technical assistance in immunohistochemistry, and to the various clinicians who collected blood specimens.

Supported in part by the Leukaemia Research Fund, UK.

Address reprint requests to Francesco Dazzi, MD, Department of Haematology, Imperial College School of Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Rd, London W12 0NN, UK; e-mail: f.dazzi@rpms.ac.uk.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal