Abstract

It has been proposed that hematopoietic and endothelial cells are derived from a common cell, the hemangioblast. In this study, we demonstrate that a subset of CD34+ cells have the capacity to differentiate into endothelial cells in vitro in the presence of basic fibroblast growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor. These differentiated endothelial cells are CD34+, stain for von Willebrand factor (vWF), and incorporate acetylated low-density lipoprotein (LDL). This suggests the possible existence of a bone marrow-derived precursor endothelial cell. To demonstrate this phenomenon in vivo, we used a canine bone marrow transplantation model, in which the marrow cells from the donor and recipient are genetically distinct. Between 6 to 8 months after transplantation, a Dacron graft, made impervious to prevent capillary ingrowth from the surrounding perigraft tissue, was implanted in the descending thoracic aorta. After 12 weeks, the graft was retrieved, and cells with endothelial morphology were identified by silver nitrate staining. Using the di(CA)n and tetranucleotide (GAAA)n repeat polymorphisms to distinguish between the donor and recipient DNA, we observed that only donor alleles were detected in DNA from positively stained cells on the impervious Dacron graft. These results strongly suggest that a subset of CD34+ cells localized in the bone marrow can be mobilized to the peripheral circulation and can colonize endothelial flow surfaces of vascular prostheses.

VASCULOGENESIS is the in situ differentiation of mesodermal precursors to angioblasts that differentiate into endothelial cells to form the primitive capillary network. Vasculogenesis is limited to early embryogenesis and is believed not to occur in the adult, whereas angiogenesis, the sprouting of new capillaries from pre-existing blood vessels, occurs in both the developing embryo and postnatal life.1,2 The basic mechanisms underlying vasculogenesis and angiogenesis are at present unclear. Several growth factors, in particular vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor Flk-1, have been shown to be critical for normal development of blood vessels.3-6 In an attempt to prove that transmural angiogenesis is responsible for endothelialization of Dacron grafts, we implanted in the canine descending thoracic aorta a Dacron graft made impermeable by silicone coating. Surprisingly, we demonstrated the presence of scattered islands of endothelial cells without any evidence of transmural angiogenesis.7 Our results are consistent with other reports demonstrating the presence of circulating endothelial cells.8-11 We have also recently shown that the neointima formed on the surface of left ventricular assist devices is colonized by CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells.12These observations suggest that vasculogenesis may not be restricted just to early embryogenesis, but may also have a physiological role in adults. Our study raised several interesting questions. First, are the endothelial cells derived from cells detached from the proximal vascular wall upstream or do they originate from the circulation? Second, if endothelial precursors circulate, are they related to circulating bone marrow-derived progenitor cells? Recently, evidence for the latter was presented by Asahara et al.13 They showed that CD34+ cells derived from the peripheral circulation form endothelial colonies, based on the ability of these colonies to incorporate acetylated LDL, express PECAM and Tie-2 receptor, and produce nitric oxide by VEGF stimulation. However, no evidence that these cells express von Willebrand factor (vWF) antigen or form homogenous endothelial monolayers was provided. Circulating CD34+ myelomonocytic progenitors can incorporate acetylated LDL and express PECAM and the VEGF receptor (VEGFR-1, Flt-1).14-17 Therefore, it is conceivable that nitric oxide production by these cells in response to VEGF could have been mediated by hematopoietic Flt-1 rather than Flk-1. Nevertheless, their study demonstrates the possibility of vasculogenesis in the adult.

In this study, we used a canine bone marrow transplantation model in which the donor and host DNA can clearly be distinguished by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based microsatellite assay to address the question of whether endothelial cells lining a vascular prosthesis can be derived from the marrow. In addition, we performed in vitro studies in which we demonstrated that CD34+ derived from bone marrow or the peripheral circulation could differentiate into endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and in vitro culture of human CD34+ cells.

Low-density mononuclear cells obtained from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood (CB), 10- to 15-week fetal liver (FL), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized peripheral blood (PB) were obtained using Ficoll separation. Low-density mononuclear cells were washed twice with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were resuspended to 1 × 108 cells/mL. A mouse IgG1 antihuman CD34+ antibody developed by one of the authors (M.A.S.M.) (11.1.6; licensed to Oncogene Science, Uniondale, NY) was added to the cells at a concentration of 50 μg/mL for 30 minutes at 4°C. The cells were washed twice with 0.1% BSA in PBS and resuspended to a concentration of 1 × 108 cells/mL, and 30 μg/mL of sheep antimouse IgG1 immunomagnetic beads (Dynal A.S., Oslo, Norway), providing a 16:1 bead-to-cell ratio, was added for 30 minutes at 4°C. The bead-positive fraction was selected with a magnetic separator, resuspended in 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), and kept overnight at 37°C in 100% humidified air with 5% CO2. The following day, the cells in the bead-negative fraction were recovered. Flow cytometry of the purified cells showed that 95% of the isolated cells were CD34+. Viability of the cells was evaluated by Trypan Blue exclusion. Isolated CD34+ cells were depleted of adherent cells by incubation with fibronectin/gelatin-coated plastic dishes at 37°C for 24 hours and removal of the nonadherent cells. This process was repeated three times and the nonadherent CD34+ cells were then reseeded onto fibronectin and gelatin-coated plastic dishes and cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in M199 medium containing VEGF (10 ng/mL), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 1 ng/mL), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1; 2 ng/mL). Colonies were stained for vWF and acetylated LDL to identify endothelial cells.

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR).

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by RT of 200 ng total RNA isolated from the purified CD34+ cells using guanidine thiocyanate and amplified by Taq DNA polymerase dissolved in PCR buffer (KlenTaq; CLONTECH) in a 50 μL reaction containing 0.2 mmol/L dNTPs and 40 pmol of Flk-1 primers (sense, 5′ CTGGCATGGTCTTCTGTGAAGCA-3′; antisense, 5′ AATACCAGTGGATGTGATGCGG-3′). The PCR profile consisted of 1 minute of denaturing at 94°C, followed by 25 cycles of 1 minute of denaturing at 94°C, 1 minute of annealing at 64°C, 2 minutes of extension at 72°C, and a final extension step of 10 minutes. The PCR product (20 μL) was separated by a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide to identify a 790-bp product. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells and bone marrow endothelial cells were used as positive controls.

Dogs and DLA typing.

Beagles, harriers, Walker hounds, and crossbred dogs were used in this study. Dogs were either bred at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center or purchased from Department of Agriculture licensed vendors located in the states of Washington and Michigan. Dogs were immunized against leptospirosis, distemper, hepatitis, and parvovirus; dewormed; and observed for disease for at least 2 months before being entered on study. Dogs weighed from 5.8 to 18.6 kg (median, 10 kg) and were 7 to 36 months old (median, 10 months old). The experimental protocols and the facilities used were approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center's Internal Animal Care and Use Committee per guidelines stipulated in the Experimental Animal Welfare Act of 1985 administered through the National Institutes of Health. Recipients were conditioned with 920 cGy total body irradiation from two opposing60Co sources. Within 4 hours of irradiation, they received an IV infusion of ≥4 × 108 marrow cells/kg followed on days 1 and 2 by 6.3 to 19.6 × 108 donor nucleated peripheral blood leukocytes/kg. To prevent graft-versus-host disease, recipients received mycophenolate mofetil (10 mg/kg BID, SC) from day 0 to 28 and cyclosporine (10 mg/kg BID, IV) from day −1 to 35.18

Blood counts were monitored until recovery to preirradiation levels. Six months after transplantation, the 6 dogs used for Dacron graft implantation showed marrow and peripheral blood cells of donor origin only as determined by standard cytogenetics and microsatellite markers.

Graft implantation.

Dacron grafts made impermeable by silicone coating were implanted into the descending thoracic aortas of the 6 beagle dogs. The 12 cm, 3-component composite graft was constructed with 4-cm expanded polytetrafluoroethylene at the ends to prevent host pannus migration to the central 4-cm Dacron graft, which was coated with silicone rubber to block perigraft tissue ingrowth. After 12 weeks, grafts were retrieved, rinsed with 5% dextrose, and silver nitrate stained (0.5% AgNO3) to help identify areas of endothelial cells.9 Häutchens were then performed for microsatellite analysis.19 Häutchens from grafts that were not silver nitrate stained were obtained for vWF immunofluoresence analysis (Fig 1). Additionally, to obtain an understanding of the cellular structure underneath the endothelial monolayer, areas close to where the Häutchens were performed on silver nitrate stained grafts were fixed in resin and processed for CD34 and hematoxylin and eosin staining.

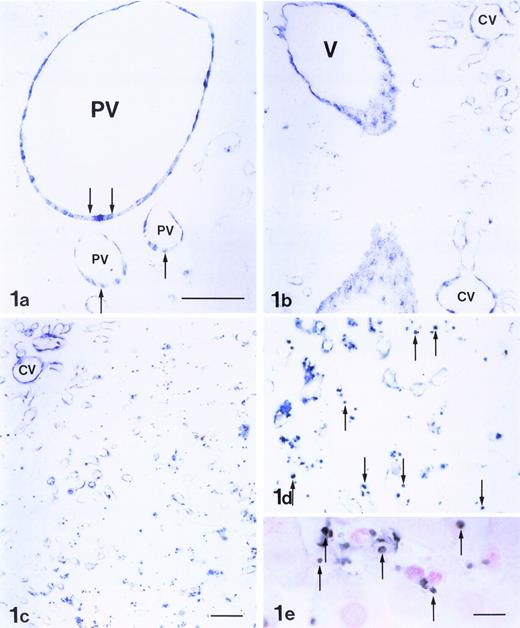

Differentiation of CD34+ hematopoietic cells to endothelial cells. (a) Adherent endothelial colonies formed after 15 to 20 days in culture incubation with VEGF/IGF/bFGF (original magnification × 400). (b) Formation of endothelial monolayer after continuous incubation with VEGF (original magnification × 600). (c) Endothelial monolayers incorporating acetylated LDL (original magnification × 600). (d) CD34+ differentiated cells that stained positively for vWF antigen (original magnification × 600). (e) CD34-selected cells expressing Flk-1 mRNA. BMEC, bone marrow endothelial cells; BM, bone marrow; CB, cord blood; PB, peripheral blood; FL, fetal liver; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

Differentiation of CD34+ hematopoietic cells to endothelial cells. (a) Adherent endothelial colonies formed after 15 to 20 days in culture incubation with VEGF/IGF/bFGF (original magnification × 400). (b) Formation of endothelial monolayer after continuous incubation with VEGF (original magnification × 600). (c) Endothelial monolayers incorporating acetylated LDL (original magnification × 600). (d) CD34+ differentiated cells that stained positively for vWF antigen (original magnification × 600). (e) CD34-selected cells expressing Flk-1 mRNA. BMEC, bone marrow endothelial cells; BM, bone marrow; CB, cord blood; PB, peripheral blood; FL, fetal liver; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

DNA extraction and microsatellite analysis.

We used a PCR-based microsatellite assay to detect polymorphism among di-(CA)n and tetra-(GAAA)n to determine the origin of the endothelial cells on the silver nitrate-stained impervious Dacron grafts.20 DNA on Häutchens was extracted and donor/recipient polymorphism was analyzed by PCR in a 50 μL reaction volume that contained High Fidelity Taq (3 U), 200 μmol/L dNTP, and 20 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP end-labeled primer and 20 pmol of the corresponding unlabeled primer. PCR was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturing at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturing at 92°C for 1 minute, annealing at 55°C for 2 minutes, and extension at 72°C for 3 minutes. The final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 minutes. Five microliters of PCR reaction product was denatured in formamide buffer at 99°C for 3 minutes and loaded on a 4% denaturing sequencing gel. The gels were exposed to Autoradiographic films (Kodax XAR-5; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) overnight at −70°C.

RESULTS

Differentiation of hematopoietic CD34+ cells into endothelial cells.

After 15 to 20 days in culture, adherent colonies of rapidly proliferating endothelial cells were observed (Fig 1a). Continuous incubation of these colonies in the presence of VEGF (10 ng/mL) resulted in the proliferation of the colonies that eventually formed cobblestone monolayers (Fig 1b). These monolayers could be passaged for up to 30 times and, compared with freshly isolated human umbilical vein endothelial cells, had 10 times more proliferative potential, as measured by thymidine uptake (data not shown). These differentiated cells had the capacity to incorporate acetylated LDL (Fig 1c) and stained positively for vWF (Fig 1d).

Because VEGF is critical for endothelial cell development, we investigated whether CD34+ cells isolated from different sources expressed Flk-1. RT-PCR of total RNA extracted from selected nonadherent CD34+ cell populations isolated from CB, bone marrow, FL, and G-CSF–mobilized PB demonstrated the presence of Flk-1 mRNA (Fig 1e). As shown in Table 1, CD34+ cells, when placed in culture, formed significant numbers of vWF-positive colonies. Although CD34+ cells derived from FL generated large numbers of endothelial colonies, it is remarkable that G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ cells derived from PB also did so. The presence of VEGF was critical for endothelial differentiation in vitro (Table 1), even though bFGF and IGF-1 enhanced endothelial colony formation. Thus, our findings suggest that the CD34+ cell may behave like a circulating endothelial progenitor cell.

VEGF Induces Differentiation of CD34+Cells Into Endothelial Colonies

| . | Peripheral Blood . | Bone Marrow . | Cord Blood . | Fetal Liver . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | 4 ± 3 | 0 | 5 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 |

| VEGF/bFGF | 2 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 6 ± 4 |

| VEGF/bFGF/IGF-1 | 4 ± 2 | 10 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | 20 ± 5 |

| bFGF/IGF-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| . | Peripheral Blood . | Bone Marrow . | Cord Blood . | Fetal Liver . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | 4 ± 3 | 0 | 5 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 |

| VEGF/bFGF | 2 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 6 ± 4 |

| VEGF/bFGF/IGF-1 | 4 ± 2 | 10 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | 20 ± 5 |

| bFGF/IGF-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CD34+ (1 × 105 cells) cells were plated in the presence of VEGF (10 ng/mL), bFGF (1 ng/mL), and IGF-1 (1 ng/mL). After 20 days the number of vWF positive colonies was quantified.

Endothelialization of vascular prostheses by marrow-derived cells.

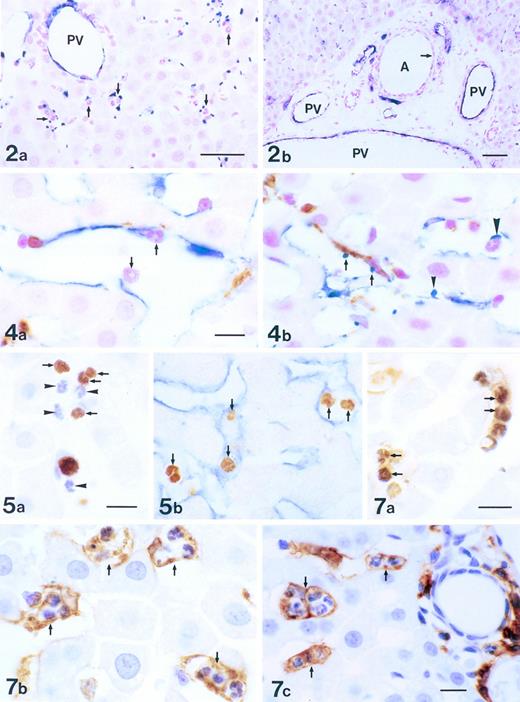

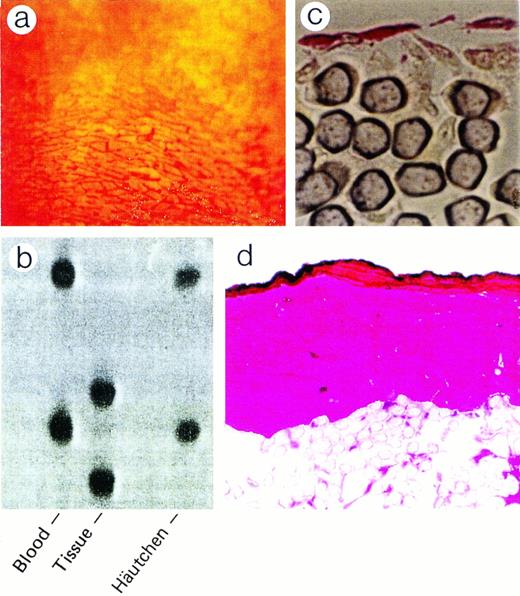

Figure 2a shows the sensitivity of the PCR-based microsatellite assay. Mixtures of cells down to 1.0% in a total of 2,000 cells could be detected as discrete bands. Häutchen preparations (Fig 2b and c) identified nucleated cells that were positive for vWF, indicating that the cells were endothelial. DNA from this Häutchen was extracted and the genotype was determined to be of donor origin (Fig 2d). Figure 3a represents a silver nitrate-stained graft showing typical polygonal-shaped endothelial cells. The endothelial monolayer was stripped from this graft using the Häutchen technique and DNA was extracted for PCR-microsatellite analysis. As shown in Fig 3b, only DNA alleles corresponding to the donor were detected. Immunostaining of the endothelial monolayer with a polyclonal antibody to CD34 was positive (Fig 3c). Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections taken from an area where the Häutchen was performed showed a single layer of endothelial cells on the flow surface of the silicone-coated Dacron graft with hardly any nucleated cells below the endothelial monolayer (Fig 3d).

Detection of bone-marrow-derived endothelial cells on vascular prostheses. (a) Sensitivity of the microsatellite assay. (b and c) Double labeling with Hoechst and FITC anti-vWF. (d) PCR analysis for (CA)n repeat polymorphism of DNA extracted from (b).

Detection of bone-marrow-derived endothelial cells on vascular prostheses. (a) Sensitivity of the microsatellite assay. (b and c) Double labeling with Hoechst and FITC anti-vWF. (d) PCR analysis for (CA)n repeat polymorphism of DNA extracted from (b).

PCR genotyping for determination of origin of silver-nitrate-stained endothelial cells. (a) Polygonal endothelial cells identified on Dacron grafts after silver nitrate staining. (b) PCR genotyping of silver nitrate-stained endothelial cells demonstrating bone marrow origin. (c) Endothelial cells stained positive for CD34 antigen. (d) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of silver nitrate-stained section.

PCR genotyping for determination of origin of silver-nitrate-stained endothelial cells. (a) Polygonal endothelial cells identified on Dacron grafts after silver nitrate staining. (b) PCR genotyping of silver nitrate-stained endothelial cells demonstrating bone marrow origin. (c) Endothelial cells stained positive for CD34 antigen. (d) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of silver nitrate-stained section.

DISCUSSION

To begin to analyze the potential role of circulating endothelial progenitor cells capable of promoting endothelialization in vivo, we performed in vitro studies focusing on the CD34+ progenitor as a possible candidate for several reasons. First, CD34, a marker for hematopoietic progenitor cells that give rise to all blood cells,21 is also found on endothelial cells in the adult and developing embryo.22-24 Second, it is believed that a single progenitor cell, the hemangioblast, can give rise to both the hematopoietic and vascular systems during embryogenesis, because common antigens are found on both endothelial and hematopoietic cells.23,25,26 Third, tyrosine kinase receptors, such as Tie, Tek, and Flk-1, that are specifically found on endothelial cells27-29 are also expressed on the hematopoietic CD34+ progenitor cell.30-32 Targeted disruption of the gene encoding Flk-1 in mice resulted in failure to develop endothelial cells, suggesting a critical role for Flk-1 in the early stages of endothelial differentiation.5 Furthermore, disruption of the VEGF gene resulted in defective development of embryonic vasculature.3,4 Also, inactivation of the Tie and Tek gene showed a critical role for these receptors in endothelial cell development, although their function may be related to events further downstream to Flk-1 and VEGF during embryonic angiogenesis.32-34 In our in vitro studies, cultured CD34+ cells in medium containing bFGF and VEGF differentiated into endothelial cell colonies, as judged by vWF-positive staining. There was an absolute requirement for VEGF in endothelial colony formation, suggesting the presence of Flk-1 on CD34 is critical for this process, consistent with previous studies demonstrating an essential role for Flk-1 in endothelial development. We provided the following controls to demonstrate that the CD34+ hematopoietic cells do indeed differentiate to endothelial cells. First, vWF staining was not detectable in freshly isolated CD34+ cells either by immunocytochemistry or flow cytometry (data not shown). Second, only nonadherent CD34+cells were obtained by culturing for 3 days on fibronectin/collagen-coated plastic dishes to remove any mature endothelial cells that are also CD34+ before the start of any experiments. Third, cells from this nonadherent population were negative for vWF just before culturing, again demonstrating lack of endothelial cells at the start of the experiments. Together, these controls make it extremely unlikely that the endothelial colonies observed in our studies were due to contaminating endothelial cells.

The presence of circulating endothelial cells was demonstrated initially in the 1960s by several investigators using Dacron grafts placed in the pig, rabbit, and dogs.8,9 In a report from 1971, endothelial cells lining the coronary arteries of a transplanted human heart were shown to be derived from the recipient and not the donor,35 and more recently endothelial cells have been shown to line a ventricular assist device.10These findings suggest what we have termed fallout endothelialization occurs in the human. More recently, evidence for fallout endothelialization in the dog also was demonstrated.7 11Although in these studies the results are all consistent with the hypothesis that circulating endothelial precursor cells can form a monolayer on a graft surface, the origin of these cells remained unclear. The possible sources from which these cells could have been derived are, first, mature endothelial cells detached from other areas of the vascular wall; second, endothelial precursor cells in circulation; or, third, endothelial precursors derived from the marrow. The major objectives of this study, using a combined in vitro and in vivo approach, were to attempt to establish the genetic origin of the endothelial cells lining the impervious Dacron grafts and to identify endothelial progenitor cells from the marrow cell population, focusing in particular on the CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cell. We used a canine marrow transplant model and a PCR-based microsatellite assay to determine the origin of the endothelial cells on an impervious Dacron graft. Because the sensitivity of the polymorphism assay is such that mixtures of cells down to 1% can be detected (Fig 1), one would assume that, if the Häutchens contained host endothelial cells, we would have consistently detected host DNA alleles, because the Häutchens analyzed were taken from areas shown by silver nitrate staining to have an extensive endothelial monolayer. The finding of a pure donor genotype strongly suggests that the endothelial cells derived from cells coming from the bone marrow.

Our experimental approach has allowed us to address the role of bone marrow derived endothelial cells in promoting endothelial monolayer formation in vivo. Our data confirm predictions based on previous in vivo studies and in vitro studies of CD34+ hematopoietic cells described herein. These data provide evidence that vasculogenesis is not only restricted to early embryogenesis, but may play a physiological role as demonstrated in this study, or may contribute to the pathology of vascular diseases in adults. Formal proof of our hypothesis awaits the development of a double-labeling method to detect genetic origin and endothelial phenotype in a single cell on a Dacron graft implanted in a marrow-transplanted dog.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank C.R. Bard, Inc and W.L. Gore, Inc for donation of the vascular graft material. We appreciate the assistance of Dorothy Mungin and Karen Englehart, Histologists; Warren Berry, Medical Photographer; Mary Ann Sedgwick Harvey, Medical Editor; and Mary-Ann Nelson, Medical Illustrator.

Q.S. and S.R. contributed equally to this study.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants No. HL36444, DK42716, and CA15704. S.R. was supported by the American Heart Association, by a Grant-In-Aid, and by NIH RO1 HL58707-01.

Address reprint requests to William P. Hammond, MD, President and Medical Director, The Hope Heart Institute, 528 18th Ave, Seattle, WA 98122; e-mail: bhammond@PMCprov.org.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

© 1998 by the American Society of Hematology.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal