Abstract

A high prevalence of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has recently been shown in a subset of B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, most of which belong to the lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma/immunocytoma subtype and are characterized by the production of a monoclonal IgM cryoglobulin with rheumatoid factor activity. To better define the stage of differentiation of the malignant B cell and to investigate the role of chronic antigen stimulation in the pathogenesis of the HCV-associated immunocytomas, we analyzed the variable (V) region gene repertoire in 16 cases with this type of tumor. The lymphoma-derived V gene sequences were successfully determined in 8 cases; 5 of them expressed the 51p1 VH gene in combination with the kv325 VL gene. Moreover, a monoclonal 51p1-expressing B-cell population was detected in 4 of the remaining immunocytomas by an allele-specific Ig gene fingerprinting assay, indicating that HCV-associated immunocytomas represent clonal proliferations of a highly selected B-cell population. Somatic mutations and intraclonal diversity were observed in all of the lymphoma V genes, and clonally related IgM and IgG VH transcripts indicative of isotype switching were present in one case. These findings are consistent with an antigen-driven process and support a role for chronic antigen stimulation in the growth and clonal evolution of HCV-associated immunocytomas.

THE HEPATITIS C VIRUS (HCV) has recently been recognized as the major etiologic factor of Type II mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC).1,2 This chronic immune-complex–mediated disease is characterized by an underlying proliferation of monoclonal B cells which typically secrete a cryoprecipitable IgMk rheumatoid factor (RF).3,4 Type II MC frequently evolves into overt B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), suggesting that chronic HCV infection can lead to both a benign and a malignant lymphoproliferative disorder.5 6

Recent studies have also shown a high prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies and HCV viremia in unselected patients with NHL, which in some series from Italy exceeded 30% of the cases.7,8 More detailed analysis of the prevalence of HCV in different histological subtypes of NHL have shown that almost half of the cases belong to the lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma/immunocytoma subtype.9-12 This type of tumor consists of a diffuse proliferation of small lymphoid cells which show maturation to plasma cells and characteristically express surface IgM and B-cell–associated antigens but lack CD5. The sites of tumor involvement include bone marrow (BM), lymph nodes (LN), spleen, and frequently peripheral blood (PB), and a monoclonal serum paraprotein of the IgM type is present in the majority of patients.13 Other types of NHLs that have been reported to be associated with a chronic HCV infection include diffuse large cell–lymphoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.14-19 However, regardless of the histological subtype, it seems that more than 50% of the patients with HCV-associated lymphomas have detectable levels of cryoglobulins in their sera.9,11,12 17

Although considerable amount of data has accumulated that supports a strong association between HCV and certain lymphoproliferative disorders, very little is known about the mechanism through which the virus could induce the expansion of particular B-cell clones. The most plausible mechanism is that certain B-cell clones proliferate as a consequence of chronic antigen stimulation either by the virus alone or by HCV-containing immune complexes.20 To investigate the role of antigen stimulation in the development of malignant HCV-associated lymphoproliferations, we have analyzed the variable region gene repertoire of 16 immunocytomas, among which 13 secreted a cryoprecipitable IgMk RF. The VH and VL gene sequences were successfully determined in 8 and 7 cases, respectively, and 5 cases were found to coexpress the 51p1 VH gene with the kv325 VL gene. Somatic mutations were detected in all of the lymphoma V gene sequences, supporting a role for antigen stimulation in the growth and clonal evolution of these tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients' characteristics and histopathologic evaluation.

Sixteen patients with lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma/immunocytoma and a chronic HCV infection were included in the study population. Diagnosis of lymphoma was based on clinical findings (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and/or cytopenia), histopathologic evaluation of LN and/or BM biopsies, and immunophenotypic analysis for surface B- and T-lymphocytic markers. Basic workup at diagnosis included a detailed history, physical examination, hematologic parameters, standard metabolic profile, urinalysis, and thoraco-abdominal computed tomographic scans. BM biopsies were performed in all patients with a Jamshidi's needle, fixed in B5 solution for 2 hours, decalcified in Decal for two hours, and embedded in paraffin. From each block representative sections were cut and stained with Hematoxilin and Eosin (H&E), Giemsa, periodic acid–Schiff, and Pearls and Gomori. The percentage of neoplastic infiltrate and the pattern of infiltration were assessed by two different hemopathologists. Paraffin sections were used for immunohistochemical staining with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method with the following monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs): anti-CD45, anti-CD20, anti-IgM, anti-IgD, anti-IgG, anti-IgA, anti-κ, and anti-λ Ig light chain (all from DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). LN biopsies were performed as clinically indicated. Histological material was fixed in formalin and routinely processed (embedded in paraffin and stained with H&E). BM and PB lymphocytes were also analyzed by flowcytometry with MoAbs against CD19, CD20, CD5, SmIg, and κ and λ light chains (all from Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Double-immunofluorescence labeling with anti-CD5 and anti-CD19 was performed in all cases to exclude B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The lymphomas were classified according to the Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms,13based on the presence of lymphoid infiltrates consisting of small ovoid lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes, and plasma cells. The lymphoid cells showed CD20 positivity and light chain restriction, whereas the plasmacytoid and plasma cells were positive for cytoplasmatic Ig.

Serum anti-HCV antibodies and HCV RNA were detected in all patients by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (HCV 2.0; Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Raritan, NJ) and reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction (RT/PCR),9,11 respectively. The HCV genotypes were determined as described elsewhere.9 11 A monoclonal IgMκ component was detected in the serum of 15 patients. Serum rheumatoid factor (normal value < 40 IU/mL) and circulating serum cryoglobulins (considered as positive if ≥1%) were present in 13 cases. At the time of first sampling, immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes showed a κ/λ ratio indicative of a clonally expanded B-cell population in 8 cases (SEG, SS, HAZ, MS, LC2, LC3, LC4, and LC5). Some relevant clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Findings in 16 HCV+ Patients With Lymphoplasmacytoid Lymphoma/Immunocytoma

| Patient . | Age/ Sex . | Involved Sites . | Associated Conditions . | HCV Genotype . | Monoclonal Component . | Cryoglobulins (Cryocrit %) . | Rheumatoid Factor (IU/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEL | 63/F | Spleen, BM, LN | LC | 1b | IgMκ | 1 | 45 |

| SEG | 45/M | Spleen, BM, PB | CPH, Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 3 | 124 |

| SS | 54/M | BM, PB | CAH, Type II MC, WM, MPGN | 2c | IgMκ | 19 | 6,070 |

| MEL | 34/F | BM | CAH, Type II MC, MPGN | 1b | IgMκ | 3 | 688 |

| HAZ | 68/M | Spleen, BM, LN, PB | LC | 1b | IgMκ | 1 | 57 |

| MS | 67/M | Spleen, BM, LN, PB | WM | 2a | IgMκ | absent | <20 |

| FAV | 50/F | BM | LC, Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 4 | 45 |

| LC1 | 47/M | BM | Type II MC, MPGN | 2a | IgMκ | 34 | 1,815 |

| LC2 | 68/F | Spleen, BM, PB | Type II MC | 2a | IgMκ | 2 | 125 |

| LC3 | 77/F | BM, PB | Type II MC, MPGN | nd | IgMκ | 2 | 824 |

| LC4 | 62/M | Spleen, BM, PB | CAH, Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 1 | 109 |

| LC5 | 57/F | Spleen, BM, PB | Type II MC, WM | 1b | IgMκ | 15 | 487 |

| LC6 | 66/M | BM | None | 2a | absent | absent | <20 |

| LC7 | 51/M | BM | CAH, Type II MC | 2a | IgMκ | 35 | 200 |

| LC8 | 58/M | BM | Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 2 | 600 |

| LC9 | 40/M | Spleen, BM, PB | MPGN | 2a | IgMκ | absent | <20 |

| Patient . | Age/ Sex . | Involved Sites . | Associated Conditions . | HCV Genotype . | Monoclonal Component . | Cryoglobulins (Cryocrit %) . | Rheumatoid Factor (IU/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEL | 63/F | Spleen, BM, LN | LC | 1b | IgMκ | 1 | 45 |

| SEG | 45/M | Spleen, BM, PB | CPH, Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 3 | 124 |

| SS | 54/M | BM, PB | CAH, Type II MC, WM, MPGN | 2c | IgMκ | 19 | 6,070 |

| MEL | 34/F | BM | CAH, Type II MC, MPGN | 1b | IgMκ | 3 | 688 |

| HAZ | 68/M | Spleen, BM, LN, PB | LC | 1b | IgMκ | 1 | 57 |

| MS | 67/M | Spleen, BM, LN, PB | WM | 2a | IgMκ | absent | <20 |

| FAV | 50/F | BM | LC, Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 4 | 45 |

| LC1 | 47/M | BM | Type II MC, MPGN | 2a | IgMκ | 34 | 1,815 |

| LC2 | 68/F | Spleen, BM, PB | Type II MC | 2a | IgMκ | 2 | 125 |

| LC3 | 77/F | BM, PB | Type II MC, MPGN | nd | IgMκ | 2 | 824 |

| LC4 | 62/M | Spleen, BM, PB | CAH, Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 1 | 109 |

| LC5 | 57/F | Spleen, BM, PB | Type II MC, WM | 1b | IgMκ | 15 | 487 |

| LC6 | 66/M | BM | None | 2a | absent | absent | <20 |

| LC7 | 51/M | BM | CAH, Type II MC | 2a | IgMκ | 35 | 200 |

| LC8 | 58/M | BM | Type II MC | 1b | IgMκ | 2 | 600 |

| LC9 | 40/M | Spleen, BM, PB | MPGN | 2a | IgMκ | absent | <20 |

Abbreviations: LC, liver cirrhosis; CAH, chronic active hepatitis; CPH, chronic persistent hepatitis; Type II MC, type II mixed cryoglobulinemia; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; WM, Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia; nd, not determined.

PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing of VH and VL region genes.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), BM aspirates, and LN biopsies using the guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform procedure.21 The PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing of the VH region genes has been described in detail elsewhere.22 Briefly, one μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamers and the GeneAmp RNA/PCR kit (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT), and then PCR amplified with a degenerate VH FWR1 primer (hFW1: 5′ AGGTGCAGCTGGA(T)GG(C)AGTC(G)T(G)GG 3′) and a Cμ specific oligonucleotide primer (hM3: 5′ GGAAAAGGGTTGGGGCGGAT 3′) located eight nucleotides downstream from the beginning of the CH1 exon. Some samples were also amplified with the FWR1 primer used in combination with a Cγ (hcG1: 5′ GGAAGACCGATGGGCCCTTG 3′) or a Cα (hA2: 5′ CGAAGACCTTGGGGCTGGTC 3′) specific primer located in the same region of the corresponding CH1 exon as the Cμ primer. The VL region genes were amplified using an equimolar mixture of 6 Vk family-specific primers (Vk1F: 5′ GTGTGCACTCCGACATCCAGATGACCCAGTCT 3′, Vk2F: 5′ GTGTGCACTCCGATGTTGTGATGACTCAGTCT 3′, Vk3F: 5′ GTGTGCACTCCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCT 3′, Vk4F: 5′ GTGTGCACTCCGACATCGTGATGACCCAGTCT 3′, Vk5F: 5′ GTGTGCACTCCGAAACGACACTCACGCAGTCT 3′, Vk6F: 5′ GTGTGCACTCCGAAATTGTGCTGACTCAGTCT 3′) and a primer from the end of the Ck gene (hCK: 5′ CTAACACTCTCCCCTGTTGAA 3′). The amplified PCR fragments were purified by electroelution from 1.2% agarose gels, ligated in the Sma I site of pUC18 (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden), and used to transform Escherichia coli strain DH5α. Clones were picked randomly, and double-stranded DNA template was prepared and sequenced using the T7 Sequencing Kit (Pharmacia LKB). Candidate germline genes were assigned by searching the VBASE directory.23 The assignment of DH gene segments was performed by comparison with published germline sequences,24,25 according to the criteria used in Yamada et al.25

Ig gene fingerprinting analysis.

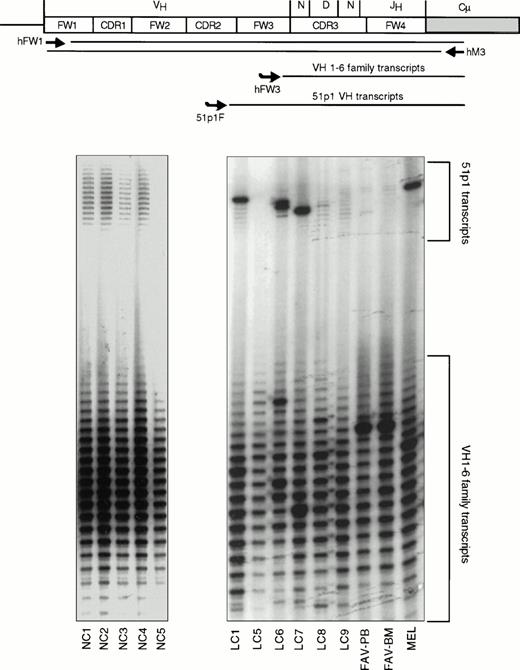

The presence of an expanded B-cell clone in the PBMC and lymph node samples was investigated by a previously described isotype-specific Ig gene fingerprinting procedure,26 with small modifications. Briefly, a 20-μL aliquot of each VH PCR was labeled by primer extension with an internal 32P-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to a conserved sequence in human VH framework 3 (FW3) regions (hFW3: 5′ CTGAGGACACGGCCGTGTATTACTG 3′, codons 84 to 92). The reaction mixtures (20 μL of the PCR sample, 10 pmol/L of 32P–end-labeled primer, 200 μmol/L dNTP, 0.5 μL of GeneAmp 10 × PCR Buffer, and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, in a final volume of 25 μL) were subjected to denaturation at 95°C for 8 minutes, annealing at 64°C for 1 minute, and extension at 72°C for 15 minutes. Two microliters of each reaction were analyzed on denaturing 6M urea 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gels, with sequencing reactions used as size markers. In some experiments the labeling reactions were performed with two radioactively labeled primers, ie, hFW3 and 51p1F (5′ GATCATCCCTATCTTTGGTACAG 3′). 51p1F is homologous to a sequence in the complementarity-determining-region 2 (CDR2) of 51p1-related alleles of the VH1-69 locus,27 and is located 113 nucleotides (nt) upstream from the hFW3 primer. With this approach the fingerprint of the 51p1-related transcripts can be related with the fingerprint of all VH transcripts. If an expanded B-cell clone expressing a 51p1-related allele is present, a dominant band will be seen in the fingerprint of 51p1-related transcripts.

Analysis of mutations.

The probability (P) that excess or scarcity of replacement (R) mutations in the CDRs or FWRs resulted by chance only was calculated with the binomial distribution model28 using Microsoft Excell software (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). The gene specific CDR Rf and FWR Rf values provided in Chang and Casali29 were used instead of the more approximate value of 0.75. The P values were calculated by analyzing the mutations from each set of clonally related transcripts in toto (counting each mutation only once),28 and also by analyzing each clone individually.

RESULTS

Clonal VH gene rearrangements in PB, BM, and LN specimens of HCV-associated immunocytomas.

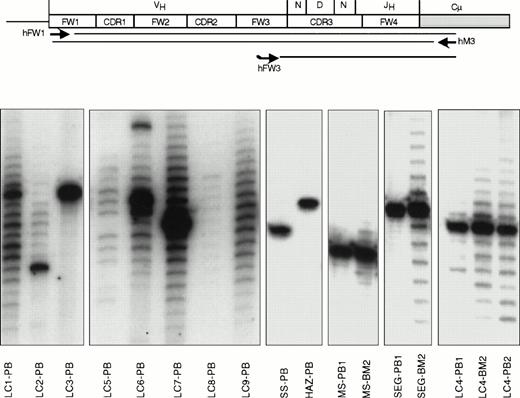

Ig gene fingerprinting analysis of IgM heavy chain transcripts was performed on mRNA extracted from PBMC, BM, and LN specimens to detect the monoclonal VH gene rearrangements of the malignant clones (Figs 1 and2). Expanded IgM-expressing B-cell clones were detected in the peripheral blood of 10 cases (MS, SS, SEG, HAZ, FAV, LC2, LC3, LC4, LC6, and LC7) and in the BM aspirates and LN biopsy of patients MS, SEG, LC4, FAV, and SEL. The rearranged lymphoma VH genes from the specimens with only a few or absent residual normal B cells (SS-PB, SEG-BM and -PB, LC2-PB, LC3-PB, HAZ-PB, LC4-BM and -PB, SEL-LN, and MS-BM and -PB) were subsequently cloned and sequenced (see below). No attempt was made to clone the lymphoma VH genes from the remaining cases because the number of polyclonal IgM+ B cells seemed to be too high to allow easy identification of the malignant clones.

Ig gene fingerprinting analysis of IgM-expressing B cells from 13 patients with HCV-associated immunocytoma. The μVH region transcripts were PCR amplified using a degenerate FW1 primer and a primer from the CH1 exon of the Cμ gene (scheme). To obtain better size fractionation and easier visualization of these fragments, radioactively labeled complementary copies of the CDR3/FW4 regions were synthesized by primer extension of a consensus 32P-labeled FW3 oligonucleotide. Autoradiograms obtained after the size separation of these fragments on sequencing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels are shown in the lower part of the figure. Monoclonal B-cell populations contain a single band in the fingerprint (samples LC3-PB, SS-PB, HAZ-PB, MS-PB1, and SEG-PB1), representing the unique CDR3 length of their VHDJH rearrangement. Polyclonal B-cell populations show a ladder of bands, consistent with the different CDR3 lengths of their VHDJH rearrangements. Entirely polyclonal B-cell populations show a Gaussian distribution of the bands in the fingerprint (samples LC8-PB, LC9-PB). A band of stronger intensity, as seen in cases LC2-PB, LC6-PB, LC7-PB, MS-BM2, SEG-BM2, LC4-BM2, and LC4-PB2, indicates a monoclonal B-cell expansion within a polyclonal B-cell population. The source of the analyzed sample is indicated after each case. Samples in cases MS, SEG, and LC4 were collected at two different time points separated by more than one year (indicated as 1 and 2).

Ig gene fingerprinting analysis of IgM-expressing B cells from 13 patients with HCV-associated immunocytoma. The μVH region transcripts were PCR amplified using a degenerate FW1 primer and a primer from the CH1 exon of the Cμ gene (scheme). To obtain better size fractionation and easier visualization of these fragments, radioactively labeled complementary copies of the CDR3/FW4 regions were synthesized by primer extension of a consensus 32P-labeled FW3 oligonucleotide. Autoradiograms obtained after the size separation of these fragments on sequencing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels are shown in the lower part of the figure. Monoclonal B-cell populations contain a single band in the fingerprint (samples LC3-PB, SS-PB, HAZ-PB, MS-PB1, and SEG-PB1), representing the unique CDR3 length of their VHDJH rearrangement. Polyclonal B-cell populations show a ladder of bands, consistent with the different CDR3 lengths of their VHDJH rearrangements. Entirely polyclonal B-cell populations show a Gaussian distribution of the bands in the fingerprint (samples LC8-PB, LC9-PB). A band of stronger intensity, as seen in cases LC2-PB, LC6-PB, LC7-PB, MS-BM2, SEG-BM2, LC4-BM2, and LC4-PB2, indicates a monoclonal B-cell expansion within a polyclonal B-cell population. The source of the analyzed sample is indicated after each case. Samples in cases MS, SEG, and LC4 were collected at two different time points separated by more than one year (indicated as 1 and 2).

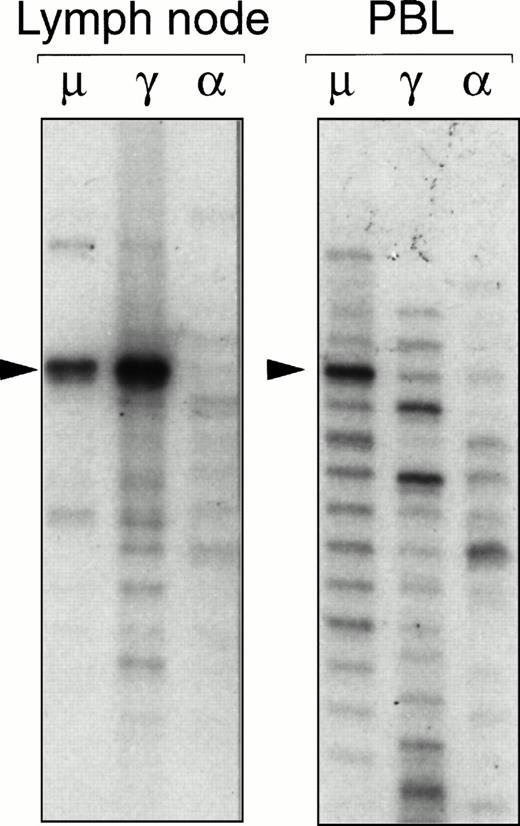

Ig gene fingerprinting analysis of IgM (μ), IgG (γ), and IgA (α) heavy chain transcripts present in a neoplastic lymph node and a PB sample obtained from patient SEL. A dominant band corresponding to the lymphoma VH gene rearrangement can be seen in the fingerprint of the μ and γ transcripts from the lymph node. A prominent band of the same size is present in the fingerprint of μ transcripts expressed by PB lymphocytes. Sequencing reactions were used as markers to determine the exact sizes of the bands.

Ig gene fingerprinting analysis of IgM (μ), IgG (γ), and IgA (α) heavy chain transcripts present in a neoplastic lymph node and a PB sample obtained from patient SEL. A dominant band corresponding to the lymphoma VH gene rearrangement can be seen in the fingerprint of the μ and γ transcripts from the lymph node. A prominent band of the same size is present in the fingerprint of μ transcripts expressed by PB lymphocytes. Sequencing reactions were used as markers to determine the exact sizes of the bands.

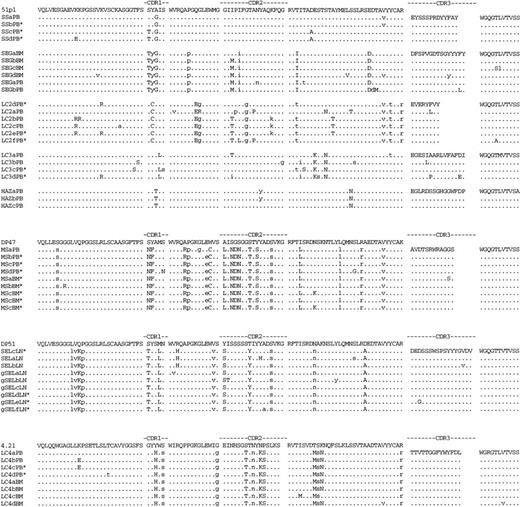

Deduced amino acid sequences of immunocytoma VH genes. The amino acid sequences of the most homologous germline VH genes are shown above the lymphoma sequences. Dashes indicate sequence identity. Amino acid replacement mutations are shown as upper case letters. The location of silent mutations in the nucleotide sequence is indicated with lower case letters. PB, BM, and LN indicate the tissue from which the lymphoma VH sequence was obtained. Sequences labeled with an asterisk were obtained from an independent set of RT/PCR, cloning, and sequencing reactions. The IgG VH sequences from SEL are labeled gSEL.

Deduced amino acid sequences of immunocytoma VH genes. The amino acid sequences of the most homologous germline VH genes are shown above the lymphoma sequences. Dashes indicate sequence identity. Amino acid replacement mutations are shown as upper case letters. The location of silent mutations in the nucleotide sequence is indicated with lower case letters. PB, BM, and LN indicate the tissue from which the lymphoma VH sequence was obtained. Sequences labeled with an asterisk were obtained from an independent set of RT/PCR, cloning, and sequencing reactions. The IgG VH sequences from SEL are labeled gSEL.

The IgG and IgA heavy chain transcripts in the samples with a monoclonal IgM+ B-cell population were similarly analyzed with the fingerprinting procedure to investigate the occurrence of immunoglobulin isotype switching in HCV-associated immunocytoma. A prominent band with an identical CDR3 length as the IgM-derived VH gene sequence was detected in the IgG fingerprint of the lymph node sample from patient SEL (Fig 2). Subsequent cloning and sequencing of the PCR products showed clonal filiation of the IgM and IgG VH gene sequences, demonstrating that a subset of the lymphoma B cells had undergone Ig heavy-chain class switching (Fig3). The inability to detect IgG- or IgA-expressing immunocytoma B cells in the remaining cases could be caused by limitations in the sensitivity of the technique, and does not imply that isotype switching is an infrequent event in HCV-associated immunocytoma.

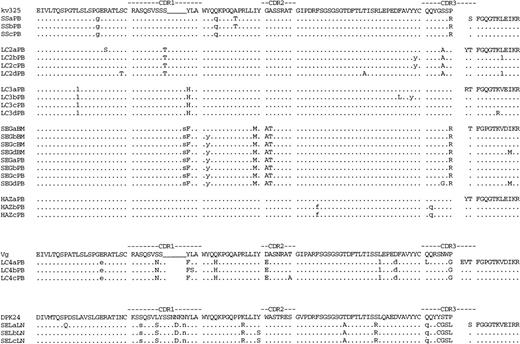

Deduced amino acid sequences of immunocytoma VL genes. The amino acid sequences of the most homologous germline VL genes are shown above the lymphoma sequences. Dashes indicate sequence identity. Amino acid replacement mutations are shown as upper case letters. The location of silent mutations in the nucleotide sequence is indicated with lower case letters.

Deduced amino acid sequences of immunocytoma VL genes. The amino acid sequences of the most homologous germline VL genes are shown above the lymphoma sequences. Dashes indicate sequence identity. Amino acid replacement mutations are shown as upper case letters. The location of silent mutations in the nucleotide sequence is indicated with lower case letters.

VH gene sequences of HCV-associated immunocytomas.

Complete nucleotide sequences of the productive VHDJH gene rearrangements were obtained for eight cases; the deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Fig 3. At least three randomly selected clones from each VH PCR were sequenced, and in most of the cases all of the VH gene sequences from a single patient were clonally related (Fig 3 and Table2). In three cases (SEG, LC4, and MS) the tumor-derived VH gene sequences were obtained from both a BM and a PB sample which were collected at two different time points separated by more than 1 year. The length of the CDR3 region of the predominant VH sequence was identical to the size of the major (or unique) band in the Ig gene fingerprint in all cases.

Distribution of Mutations in VH Genes of HCV-Associated Lymphomas

| Patient . | VH Family . | Tumor Seq/ Clones Seq (Source) . | VH Gene . | % Homology . | R:S Mutations . | P* . | D Gene . | JH Gene . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | VHI | 4/4 (PB) | 51p1 | 99.0 | CDR | 2:0 | .27 | DN4 | JH4b |

| FWR | 2:1 | .1 | |||||||

| SEG | VHI | 4/5 (BM) 2/3 (PB) | 51p1 | 96.3 | CDR FWR | 3:3 3:3 | .25 .004 | DK1 | JH4b |

| LC2 | VHI | 6/8 (PB) | 51p1 | 95.6 | CDR | 4:3 | .14 | DXP1 | JH4b |

| FWR | 8:7 | .0008 | |||||||

| LC3 | VHI | 4/4 (PB) | 51p1 | 97.7 | CDR | 2:3 | .11 | DN4 | JH3b |

| FWR | 6:5 | .004 | |||||||

| HAZ | VHI | 3/3 (PB) | 51p1 | 99.1 | CDR | 1:1 | .4 | D21-9 | JH5b |

| FWR | 1:0 | .19 | |||||||

| LC4 | VHIV | 4/6 (BM) 4/4 (PB) | VH4.21 | 95.6 | CDR FWR | 4:2 3:4 | .19 .0002 | DA1/D22-12 | JH2 |

| SEL | VHIII | 9/10 (LN) | DP51 | 95.2 | CDR | 6:2 | .13 | DN1 | JH6b |

| FWR | 3:8 | .00005 | |||||||

| MS | VHIII | 5/6 (BM) 4/4 (PB) | DP47 | 93.1 | CDR FWR | 9:1 4:7 | .026 .00005 | D4 | JH5a |

| Patient . | VH Family . | Tumor Seq/ Clones Seq (Source) . | VH Gene . | % Homology . | R:S Mutations . | P* . | D Gene . | JH Gene . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | VHI | 4/4 (PB) | 51p1 | 99.0 | CDR | 2:0 | .27 | DN4 | JH4b |

| FWR | 2:1 | .1 | |||||||

| SEG | VHI | 4/5 (BM) 2/3 (PB) | 51p1 | 96.3 | CDR FWR | 3:3 3:3 | .25 .004 | DK1 | JH4b |

| LC2 | VHI | 6/8 (PB) | 51p1 | 95.6 | CDR | 4:3 | .14 | DXP1 | JH4b |

| FWR | 8:7 | .0008 | |||||||

| LC3 | VHI | 4/4 (PB) | 51p1 | 97.7 | CDR | 2:3 | .11 | DN4 | JH3b |

| FWR | 6:5 | .004 | |||||||

| HAZ | VHI | 3/3 (PB) | 51p1 | 99.1 | CDR | 1:1 | .4 | D21-9 | JH5b |

| FWR | 1:0 | .19 | |||||||

| LC4 | VHIV | 4/6 (BM) 4/4 (PB) | VH4.21 | 95.6 | CDR FWR | 4:2 3:4 | .19 .0002 | DA1/D22-12 | JH2 |

| SEL | VHIII | 9/10 (LN) | DP51 | 95.2 | CDR | 6:2 | .13 | DN1 | JH6b |

| FWR | 3:8 | .00005 | |||||||

| MS | VHIII | 5/6 (BM) 4/4 (PB) | DP47 | 93.1 | CDR FWR | 9:1 4:7 | .026 .00005 | D4 | JH5a |

*P is the probability for obtaining the observed number of R mutations by chance. The P values were determined with the binomial probability model by analyzing all mutations from each set of clonally related transcripts together (counting each mutation only once). However, the P values were not significantly different when each clone was analyzed separately (data not shown).

The germline counterparts of the lymphoma VH genes were assigned by searching the VBASE directory.23 Five of the VH genes shared more than 95% homology with the VHI family gene 51p1 (Table 2). Two other cases expressed VH genes most closely related to the VHIII family members DP47 and DP51, whereas the last VH gene sequence was most homologous to the VHIV family gene VH4.21.

All of the lymphoma VH genes showed numerous single nucleotide differences from the candidate germline genes (Fig 3). These nucleotide substitutions were apparently somatic mutations because they were obtained again after a second set of RT/PCR, cloning, and sequencing reactions. Moreover, many of the mutations in the lymphoma VH genes obtained from the first samplings in patients SEG, LC4, and MS were found also in the lymphoma VH sequences obtained from the second samplings. Finally, most of the mutations found in the lymph node specimen of patient SEL were shared between the clonally related IgM and IgG VH gene sequences. On the other hand, certain mutations were found only in a single clone or were shared only among some of the clones of a given VDJ rearrangement. Mutations of this kind were detected in all of the lymphomas, indicating that intraclonal heterogeneity of VH gene sequences is a frequent phenomenon in HCV-associated immunocytoma.

VL gene sequences of HCV-associated immunocytomas.

A predominant or unique VK sequence was obtained in seven cases (Fig 4). Sequencing of seven clones from the last case (patient MS) yielded seven different VKsequences. The inability to detect the lymphoma VK sequence in this case was presumably because of considerable differences with the sequence of the 5′ VK PCR primers; the VHgene of this case was most extensively mutated, and the same is likely to have happened with the lymphoma VK gene.

Allele-specific Ig gene fingerprinting of IgM-expressing B cells. A schematic representation of the procedure is shown at the top of the figure. The positions of the PCR primers (hFW1 and hM3) and the primers used for labeling the PCR products (hFW3 and 51p1F) are indicated. The autoradiograms show the analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes from five normal controls (NC1-5) and eight cases with HCV-associated immunocytoma (a BM sample from MEL was also analyzed). The locations of the bands corresponding to 51p1 transcripts and all VH transcripts are indicated. Expanded 51p1-expressing B-cell clones can clearly be seen in cases LC1, LC6, LC7, and MEL.

Allele-specific Ig gene fingerprinting of IgM-expressing B cells. A schematic representation of the procedure is shown at the top of the figure. The positions of the PCR primers (hFW1 and hM3) and the primers used for labeling the PCR products (hFW3 and 51p1F) are indicated. The autoradiograms show the analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes from five normal controls (NC1-5) and eight cases with HCV-associated immunocytoma (a BM sample from MEL was also analyzed). The locations of the bands corresponding to 51p1 transcripts and all VH transcripts are indicated. Expanded 51p1-expressing B-cell clones can clearly be seen in cases LC1, LC6, LC7, and MEL.

The VL sequences were analyzed essentially as described for the VH sequences, with a minimum of three clones sequenced from each VK PCR. Five of the sequences were most homologous to the VKIII family gene kv325 (Table3). One of the remaining two cases expressed the VKIII family gene Vg, whereas the last sequence was most closely related to the VKIV family gene DPK24. Interestingly, all of the lymphoma kv325 VL genes were paired with a 51p1-derived VH gene. Somatic mutations and intraclonal diversity were also observed in the VLsequences, although to an apparently lesser extent than in the case of the lymphoma VH sequences.

Distribution of Mutations in VL Genes of HCV-Associated Lymphomas

| Patient . | VL Family . | Tumor Seq/ Clones Seq (source) . | VL Gene . | % Homology . | R:S Mutations . | P* . | JL Gene . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | VKIII | 3/3 (PB) | kv325 | 98.9 | CDR | 0:0 | .49 | JK2 |

| FWR | 1:2 | .16 | ||||||

| SEG | VKIII | 4/6 (BM) 4/4 (PB) | kv325 | 97.4 | CDR FWR | 4:1 0:1 | .008 .005 | JK3 |

| LC2 | VKIII | 4/5 (PB) | kv325 | 98.9 | CDR | 2:0 | .11 | JK2 |

| FWR | 1:0 | .16 | ||||||

| LC3 | VKIII | 4/4 (PB) | kv325 | 99.3 | CDR | 1:0 | .27 | JK1 |

| FWR | 0:1 | .17 | ||||||

| HAZ | VKIII | 3/3 (PB) | kv325 | 99.3 | CDR | 0:1 | .7 | JK2 |

| FWR | 0:1 | .17 | ||||||

| LC4 | VKIII | 4/4 (PB) | Vg | 97.0 | CDR | 4:0 | .033 | JK3 |

| FWR | 1:3 | .004 | ||||||

| SEL | VKIV | 3/7 (LN) | DPK24 | 95.4 | CDR | 5:3 | .16 | JK4 |

| FWR | 4:0 | .02 | ||||||

| Patient . | VL Family . | Tumor Seq/ Clones Seq (source) . | VL Gene . | % Homology . | R:S Mutations . | P* . | JL Gene . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | VKIII | 3/3 (PB) | kv325 | 98.9 | CDR | 0:0 | .49 | JK2 |

| FWR | 1:2 | .16 | ||||||

| SEG | VKIII | 4/6 (BM) 4/4 (PB) | kv325 | 97.4 | CDR FWR | 4:1 0:1 | .008 .005 | JK3 |

| LC2 | VKIII | 4/5 (PB) | kv325 | 98.9 | CDR | 2:0 | .11 | JK2 |

| FWR | 1:0 | .16 | ||||||

| LC3 | VKIII | 4/4 (PB) | kv325 | 99.3 | CDR | 1:0 | .27 | JK1 |

| FWR | 0:1 | .17 | ||||||

| HAZ | VKIII | 3/3 (PB) | kv325 | 99.3 | CDR | 0:1 | .7 | JK2 |

| FWR | 0:1 | .17 | ||||||

| LC4 | VKIII | 4/4 (PB) | Vg | 97.0 | CDR | 4:0 | .033 | JK3 |

| FWR | 1:3 | .004 | ||||||

| SEL | VKIV | 3/7 (LN) | DPK24 | 95.4 | CDR | 5:3 | .16 | JK4 |

| FWR | 4:0 | .02 | ||||||

*P is the probability for obtaining the observed number of R mutations by chance. The P values were determined with the binomial probability model by analyzing all mutations from each set of clonally related transcripts together (counting each mutation only once). However, the P values were not significantly different when each clone was analyzed separately (data not shown).

Distribution of mutations in lymphoma VH and VL genes.

To address the possible role of antigen selection in the clonal evolution of the HCV-associated immunocytomas, we investigated the distribution of replacement and silent mutations in the CDRs of the VH and VL genes. Although most of the sequences showed a higher replacement-to-silent (R:S) ratio in the CDRs than in the FWRs, the probability for obtaining the observed number of R mutations in the CDRs by chance alone was smaller than 0.05 only in the case of one VH gene (case MS) and two VL genes (cases SEG and LC4). The absence of significant clustering of replacement mutations in the CDRs argues against selection for variants with higher antigen binding affinity.28 29 On the other hand, lower numbers of R mutations than expected by chance alone were evident in most of the FWRs, indicating selective pressure for maintenance of functional Ig molecules.

Preferential expression of the 51p1 VH gene in HCV-associated immunocytomas.

The 51p1/Humkv325 gene combination was expressed in five of the eight lymphomas for which VH and VL gene sequences were determined. The remaining eight lymphomas were screened for monoclonal 51p1 rearrangements using an allele-specific Ig gene fingerprinting assay. This was performed by including a 51p1-specific oligonucleotide in the labeling step of the Ig gene fingerprinting analysis, which allows detection of a monoclonal 51p1-expressing B-cell population among IgM+ B cells expressing other VH genes (Fig 5). The specificity of this assay was previously established by analyzing more than 30 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cases with characterized VH gene sequences (only cases with a monoclonal 51p1 rearrangement showed a single band in the 51p1 fingerprint), and more than 60 cases without any lymphoproliferative disorder (DGE, unpublished observations, July 1997). Most of the latter cases showed a polyclonal pattern of 51p1 transcripts (examples are NC1-4 in Fig 5), whereas in the remaining cases 51p1 transcripts could not be detected (NC5 in Fig5). This type of normal pattern was observed in cases LC5, LC8, LC9, and FAV, whereas the remaining four cases (LC1, LC6, LC7, and MEL) showed a dominant single band in the 51p1 fingerprint, indicating a monoclonal expansion of 51p1-expressing IgM+ B cells. Thus, it seems probable that these four lymphomas also expressed Ig molecules encoded by the 51p1 VH gene.

DISCUSSION

Nucleotide sequence analysis of VH and VL genes has provided useful information regarding the pathogenesis and the stage of differentiation for many B-cell neoplasms.30-41The presence of somatic mutations suggests that the malignant B cells have passed the germinal center stage of differentiation, whereas the finding of a restricted V gene repertoire and a high frequency of replacement mutations in the CDRs are indicative of a role for antigen selection in the pathogenesis of the disease. We now show that the antibodies expressed by the malignant B cells in HCV-associated immunocytomas are preferentially encoded by a restricted set of VH and VL genes. The 51p1/kv325 gene combination encoded the variable regions in five of the eight cases for which complete nucleotide sequences were determined. Considering also the data obtained with the Ig gene fingerprinting technique, it seems that 9 of the 16 VH genes were derived from the 51p1 gene, indicating that this VH gene is highly overrepresented in HCV-associated immunocytoma.

The frequent usage of the 51p1/kv325 combination in HCV-associated immunocytomas is not surprising, considering that the malignant B cells in most cases produced a monoclonal cryoglobulin with RF activity (8 of the 13 cases with a type II cryoglobulin had a monoclonal 51p1 rearrangement). Early studies using anti-idiotypic antibodies have shown that more than 60% of monoclonal RFs from patients with type II MC express the Wa cross-reactive idiotype (CRI), which, in turn, in more than 70% of the cases is associated with the light chain CRI 17.109 and the heavy chain CRI G6.5 The latter two CRIs are characteristic for VL and VH regions encoded by germline kv325 and 51p1 genes, respectively. Thus, these data indicate that HCV-associated immunocytoma most likely represents the malignant counterpart of type II MC.

The VH and VL gene sequences from all of the HCV-associated immunocytomas showed a number of nucleotide differences with respect to their germline counterparts. In addition, substantial intraclonal VH and/or VL gene diversity was evident in each case, consistent with an ongoing somatic hypermutation process in the tumor cells subsequent to the neoplastic transformation. A similar phenotype has been observed in a number of other B-cell malignancies such as follicular lymphoma,30gastric and salivary gland MALT lymphoma,35,40 Burkitt's lymphoma,36 and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance,37 indicating that the malignant events in these neoplasms might have occurred at a similar stage of B-cell differentiation.

Clonally related transcripts of the IgM and IgG heavy chain isotype were detected in one of the HCV-associated immunocytomas, providing evidence for isotype switching in a subset of the malignant B cells. Isotype switching and somatic hypermutation are processes which typically occur in the germinal centers of lymphoid tissues during a T-cell–dependent antibody response, and are consistent with a role for antigen stimulation in the clonal evolution of the lymphoma. The RF activity of the Igs from most of the HCV-associated immunocytomas suggests that the proliferation of the neoplastic B cells was driven by immune complexes composed of polyclonal IgG and HCV. T cells specific for IgG Fc are normally deleted,42 but the RF-producing B cells may obtain T-cell help from HCV-specific T cells while presenting peptides derived from HCV proteins present in the immune complexes.43 Interestingly, however, the pattern of somatic mutations in the HCV-associated immunocytoma V genes is not suggestive for selection of changes which could increase the affinity for the antigen. Rather, the low number of replacement mutations in the CDRs is indicative of selection against mutations which could generate high-affinity antibodies. This is most clearly seen in the case of the 51p1-encoded VH regions which have an overall R:S ratio in the CDRs of only 1.2 (12:10), which is substantially lower than the R:S ratio of 3.6 expected from random accumulation of nucleotide changes in the absence of selective pressure.29 A high R:S ratio which was significantly different from the one expected for random mutations was seen only in the VH CDRs of the lymphoma immunoglobulin that lacked RF activity (patient MS, Table 2). The CDRs of the light chains similarly lacked high R:S ratios, which was especially evident in the case of the kv325-encoded VL domains. A low number of R mutations was also observed in the FWRs of most of the VH and VL domains. Negative selection against R mutations in the FWRs is consistent with selective pressure for maintenance of functional Ig molecules, and further indicates the requirement for a functional B-cell receptor in the clonal evolution of the HCV-associated immunocytomas.

Rheumatoid factor antibodies that are induced after immunization of healthy donors are frequently encoded by the 51p1/kv325 combination,44 indicating a common cellular origin with the monoclonal RFs of type II MC and HCV-associated immunocytoma. Nucleotide sequence analysis of 51p1-encoded RFs from healthy immunized donors also shows a strong selection against R mutations in the CDRs, and moreover, no increase in the affinity for the Fc region of IgG with the accumulation of mutations.45 Intraclonal diversity and absence of significant clustering of R mutations in the CDRs has also been observed in a 51p1/kv325-encoded RF from a patient with type II MC.46 Also in this case the affinity for the Fc region of IgG did not change after substituting the mutated 51p1 and kv325 genes with their germline counterparts.47 Thus, although all of the above data indicate that antigen stimulation can lead to the proliferation, somatic mutation, and isotype switching of RF-expressing B cells, it also seems that B cells expressing high affinity RF receptors are either not selected or are eliminated by peripheral tolerance mechanisms.48-50

Preferential use of the 51p1 gene has also been observed in CLL, with a prevalence of more than 20% in particular geographic areas (31,51 and DGE, unpublished observations, July 1997). However, unlike the HCV-associated immunocytomas, the 51p1 VH sequences in CLL are almost exclusively unmutated and usually have significantly longer CDR3 regions.51,52 A more striking similarity regarding V gene repertoire and somatic hypermutation exists between HCV-associated immunocytoma and salivary gland MALT lymphoma. In two recent studies by Bahler et al40 53 the 51p1 gene was found in 10 of the 18 VH sequences and was associated with a kv325 VLregion in all cases in which the VL sequence was reported. Although the antigen specificity of the lymphoma Igs in this study is unknown, it is interesting to note that salivary gland MALT lymphomas are typically associated with Sjogren's syndrome, which is frequently characterized by the presence of RFs and cryoglobulins in patients' sera. Somatic hypermutation, intraclonal diversity, and selection against R mutations in the CDRs was also observed in this study, indicating similar events in the pathogenesis of HCV-associated immunocytomas and salivary gland MALT lymphomas.

In summary, the data presented in this study indicate that HCV-associated immunocytomas represent clonal proliferations of a highly selected B-cell population. The tumor cells from most of these cases secrete a cryoprecipitable RF that is frequently encoded by the 51p1 VH gene in combination with the kv325 VLgene. The V genes in these lymphomas undergo changes typical of a T-cell–dependent antibody response, indicating a role for chronic antigen stimulation by HCV-containing immune complexes in the clonal evolution of HCV-associated immunocytomas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Nicholas Chiorazzi for valuable comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported in part by a grant no. 42 from the Istituto Superiore Di Sanita within the frame of the Primo Progetto Di Ricerca Epatite Virale.

Address reprint requests to Dimitar G. Efremov, MD, PhD, ICGEB, Area Science Park, Padriciano 99, 34012 Trieste, Italy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal