HEMATOPOIESIS IS A life-long process responsible for replenishing both hematopoietic progenitor cells and mature blood cells from a pool of pluripotent, long-term reconstituting stem cells.1 The daily turnover in a normal adult of approximately 1012 blood cells is tightly regulated, involving, in part, a complex interaction between soluble and membrane-bound stimulatory and inhibitory cytokines and their corresponding receptors.2-4 The molecular cloning of these hematopoietic growth factors (HGFs) and their receptors has been instrumental in delineating the pathways that lead from a single hematopoietic stem cell to the various terminally differentiated cells in the hematopoietic system.

Although a number of cytokines have effects on progenitor and stem cells in vitro or in vivo, two cytokines discovered in the early 1990s, c-kit ligand and flt3 ligand, appear to have unique and nonredundant activities on primitive progenitor/stem cells.

Because of the broad range of hematopoietic activities mediated through interaction of c-kit ligand (KL) and flt3 ligand (FL) with their receptors, it is beyond the scope of this report to review the effects of these proteins outside of the hematopoietic system. Rather, we will focus on the discovery, structure, function, expression, and biological roles of these two ligand-receptor pairs. Special attention will be directed towards hematopoietic activities in which KL and FL show either distinct or synergistic effects. For a more detailed overview of other hematologic and immunologic effects of KL and FL, other reviews can be recommended.5-8 Two subjects have been deliberately left out of this report, because they are deserving of their own separate reviews (signal transduction pathways involving c-kit and flt3 and activities of KL and FL outside of the hematopoietic system).

DISCOVERY OF THE DOMINANT WHITE SPOTTING (W) LOCUS AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THE c-kit TYROSINE KINASE RECEPTOR

The W (dominant White spotting) locus in mice was first described in the early 1900s.9,10 Mice afflicted with mutations at the W locus were originally identified, as the name implies, by the presence of a white spot on the bellies of pigmented mice. Detailed examination of these mice showed that the mutation was pleiotropic. The mice suffer from defects in germ cell development (manifested as reproductive difficulties) and in hematopoiesis (characterized by a macrocytic anemia). Over the years, at least 20 allelic variants of the W locus have been described; most have a similar, although not identical, phenotype.9,10 The W locus is on chromosome 5 and is one of the most mutable loci in mice.9 10

A central question that remained was what kind of protein the Wlocus encoded, and how did it affect so many different tissues. A breakthrough came in 1988 when it was shown that the W locus encoded a tyrosine kinase receptor known as c-kit.11,12 The c-kit protein has the same general structure as four other tyrosine kinase receptors: c-fms, the receptor for macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)13-15; flt316-19; and both of the receptors for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF; designated as A and B).20-23 Each of these receptors is approximately 1,000 amino acids in length, has five Ig-like domains in the extracellular region, and contains a split catalytic domain in the cytoplasmic region that phosphorylates tyrosine residues in specific target proteins after activation of the receptor by ligand. The exact defect in the c-kit receptor has been identified at the molecular level for a number of alleles of theW locus24-28 (see section on genetic alterations in c-kit and KL genes).

THE STEEL (Sl) LOCUS AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TOW

Many years after the discovery of the W locus, a mutation in mice that had a phenotype virtually identical to W mice was identified.29 Despite the similarities in phenotype, this new mutation, designated Steel (Sl), was localized to mouse chromosome 10, so it was clearly not allelic with the W locus on chromosome 5.10,30 Because mutations on two different chromosomes had the same complex phenotype that affects pigmentation, germ cells, and hematopoiesis, researchers hypothesized that there would be some relationship between the proteins encoded at these two loci. Elizabeth Russell, who did much of the pioneering research on both of these mutations, suggested (years before the discovery that theW locus encoded c-kit and that c-kit was a receptor) that the W and Sl loci might encode a receptor and its cognate ligand.10

CLONING OF THE STEEL FACTOR (THE c-kit LIGAND, KL)

With the recognition that the W locus encoded c-kit,11,12 the search for the c-kit ligand began in earnest. A number of approaches were undertaken to identify the protein encoded at the Sl locus, including chromosome walking31 and expression cloning. However, the successful approach turned out to be the purification of the Steel factor protein.

The cloning of a cDNA encoding the Steel factor was reported simultaneously by three different groups, each of which discovered a different source of the factor.32-34 All three groups used a similar approach; they first purified the protein from medium conditioned by a cell line, obtained N-terminal amino acid sequence, and then made degenerate oligonucleotide primers based on the protein sequence to isolate cDNA clones by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The three groups named this protein mast cell growth factor, stem cell factor, and c-kit ligand (see below). In this review, we will use the name c-kit ligand (KL) for the protein that binds to the c-kit receptor and is encoded at the Sl locus on mouse chromosome 10 (see below).32,35 36

DISCOVERY OF THE Flt3 TYROSINE KINASE RECEPTOR

In contrast to the discovery of c-kit, analysis of mouse mutations did not play a role in the discovery of the flt3 receptor. This receptor was isolated independently by two groups using distinct cloning strategies.18,19,41 One group used low stringency hybridization with a DNA probe from the M-CSF receptor (c-fms) to isolate a portion of a related DNA sequence that was named flt3 (fms-like tyrosine kinase 3).41 The partial clone was then used to isolate a full-length receptor clone.18

A second group used degenerate oligonucleotides (based on conserved regions within the kinase domain of tyrosine kinase receptors) in a PCR-based strategy to isolate a novel receptor fragment from highly purified murine fetal liver stem cells.19 This fragment was used to isolate a full-length receptor clone given the name flk-2 (fetal liver kinase 2). The flt3/flk-2 receptor has also been referred to as Stk-1 (stem cell kinase-1),17 but this name is not widely used, perhaps because it has been previously designated to denote a gene regulating stem cell kinetics42 as well as a different receptor tyrosine kinase of the met/sea/ron family.43

Comparison of the murine flt3 and flk-2 receptor sequences showed that these sequences differ by only two amino acids in their extracellular domains.44 In contrast, a large number of amino acid differences were seen in a region near their C-terminal ends. The murine flt3 receptor sequence has been independently confirmed by several groups,44-46 and the human receptor sequence is directly homologous to the murine flt3, but not the murine flk-2 sequence.16,17 No independent confirmation of the sequence of flk-2 has been reported. Differences between flt3 and flk-2 sequences are not a result of tissue-specific expression of distinct isoforms.46 The differences in the murine flt3 and flk-2 sequences have never been fully explained, and the validity of the sequence reported as flk-2 is still unclear.47 As a result of this, we refer to the receptor as flt3 and to its ligand as flt3 ligand (FL).

CLONING OF THE LIGAND (FL) FOR THE Flt3 RECEPTOR

A soluble form of the flt3 receptor was the key reagent used by two groups to clone FL. Lyman et al48 screened a variety of cell lines to look for one that expressed a ligand on the cell surface that was capable of binding the soluble receptor. A murine T-cell line was identified that specifically bound the soluble flt3 receptor. The ligand was then cloned from a cDNA expression library made from mRNA isolated from these cells.

An alternative approach employed by Hannum et al49 used an affinity column made with the mouse flt3 receptor extracellular domain to purify FL from medium conditioned by a murine thymic stromal cell line. N-terminal sequencing of the purified protein generated a short amino acid sequence, which was then used to design degenerate oligonucleotide primers to amplify a portion of the FL gene by PCR. Isolation of this FL gene fragment led to the cloning of a full-length murine cDNA.

SPECIES SPECIFICITY OF KL AND FL

No restriction in species specificity has been observed with regard to FL binding or biological activity. Both the mouse and human ligand proteins are fully active on cells bearing either the mouse or human receptors.51 The human FL protein has been found to stimulate mouse, cat (Janis Abkowitz, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, unpublished data), rabbit, nonhuman primate, and human cells. This lack of species specificity of FL is in marked contrast to KL, where the mouse protein is active on human cells but the human protein has limited activity on murine cells.33 Analysis of chimeric mouse/human KL proteins has helped define regions of the protein that regulate its species-specific action.52

STRUCTURE OF THE c-kit AND Flt3 RECEPTORS

The murine and human c-kit receptors are each 976 amino acids in length, have nine potential sites for N-linked glycosylation in their extracellular domains,53,54 and are glycosylated at one or more of these sites.54,55 Immunoprecipitation shows two proteins of approximately 140 kD and 155 kD54; the predicted size of the protein backbone alone is approximately 108 kD. Pulse-chase analysis has shown that the larger 155-kD protein arises from the smaller protein,56 presumably due to glycosylational processing of the protein from one containing high mannose carbohydrates to one containing complex carbohydrates. Furthermore, cell surface iodination of c-kit-expressing cells radiolabels only the larger protein.54 The size of the c-kit protein varies between tissues,55 although whether this is due to differential glycosylation or expression of different isoforms is unclear (see below).

The murine (1,000 amino acids) and human (993 amino acids) flt3 receptors have 9 and 10 potential sites for N-linked glycosylation, respectively, in their extracellular domains16-19 and are also glycosylated at one or more of these sites.44Immunoprecipitation shows two proteins of 130-143 kD and 155-160 kD44,57,58; the predicted size of the protein backbone alone is approximately 110 kD. As with c-kit, pulse-chase analysis has shown that the larger protein arises from the smaller protein44; again, this most likely results from glycosylational processing. Consistent with this interpretation is the finding that only the 158-kD species is found on the cell surface.44 There do not appear to be any O-linked sugars on the protein.59

BINDING OF KL AND FL TO THEIR RECEPTORS

A number of studies have measured the binding affinity of KL to the c-kit receptor60-64 and that of FL to the flt3 receptor.65 Both high (kd, 16 to 310 pmol/L) and low (kd, 11 to 65 nmol/L) affinity binding of KL to its receptor have been reported.60,61,63 Some primary cells and cell lines have only high- affinity sites, whereas others have both.61,63 Neither the number of receptors per cell nor the finding of one or two classes of receptors can be correlated with the ability of cells to proliferate in response to KL.60

The binding affinity of human FL for the flt3 receptor on human myeloid leukemia cells has been estimated to be 200 to 500 pmol/L,65 and only high-affinity binding is seen. The high binding affinity of FL for the flt3 receptor is therefore in the same range of affinities as the binding of KL to c-kit.

The c-kit and flt3 receptors each have five Ig-like domains in their extracellular regions. Mutagenesis studies on c-kit have shown that the first three domains are both necessary and sufficient for binding of ligand66 and that the fourth Ig-like domain is required for dimerization of the receptor,66 although this has recently been called into question.67 Several models have been proposed for binding of KL to c-kit,66-71 but it is beyond our scope to review these studies. Whatever the mechanism responsible for the formation of the complex, the ultimate result is that a dimeric form of the ligand is associated with a dimeric form of the receptor, which results in signal transduction. Although similar studies have not been performed with FL and flt3 receptors, a similar process most likely occurs with this ligand-receptor pair.

ISOFORMS OF THE c-kit AND Flt3 RECEPTORS

Analysis of independently derived cDNA clones has shown that there are two isoforms of both the murine and human c-kit-encoded protein.72 These c-kit receptor isoforms differ by four amino acids (glycine-asparagine-asparagine-lysine, abbreviated GNNK) that are either present or absent just upstream of the transmembrane domain. The different isoforms result from alternative splicing of c-kit mRNAs at a cryptic splice donor site located at the 3′ end of exon 9.73 Although it is not clear if physiologic differences occur because of ligand signaling via one c-kit isoform versus another, ligand-independent constitutive phosphorylation of the receptor occurs only in the isoform missing these four amino acids.72

Crosier et al74 examined expression of the two c-kitisoforms in both leukemic cell lines and in primary acute myeloid leukemias; both isoforms appeared to be expressed in all of the cells examined, with the ratio of GNNK− to GNNK+isoforms ranging from 10:1 to 15:1. A second study confirmed the expression of both isoforms in a series of acute myeloid leukemias.75

In addition to the isoforms discussed above, other variants have been seen in the c-kit receptor. Alternative splicing of mRNAs has been shown to insert an extra serine residue in the cytoplasmic domain at position 715; a survey of human cell lines and acute myeloid leukemia samples shows that both of these isoforms are normally expressed.74

Finally, soluble c-kit receptors are produced by some hematopoietic cell lines in culture,64 and a soluble version of c-kit has been found in human serum at high levels (324 ± 105 ng/mL).76 How this soluble c-kitreceptor is generated is unknown, although it does appear capable of binding KL.60 64 In each of the cases described above, the physiologic significance, if any, of the receptor variant is unknown.

Fewer isoforms of the flt3 receptor have been reported than have been seen with c-kit. One isoform of the murine flt3 receptor is missing the fifth of the five Ig-like regions in the extracellular domain as a result of the skipping of two exons during transcription.77 This alternative isoform is present at lower levels than the wild-type receptor, although it is able to bind ligand and is phosphorylated as a result of this binding. Thus, the fifth Ig domain of flt3 is not required for either ligand binding or receptor phosphorylation. Similarly, the c-kit receptor requires only the first three Ig-like domains for ligand binding.66 The physiologic significance of this flt3 receptor isoform is presently unknown, and a soluble version has not yet been identified in human serum.

STRUCTURES OF THE KL AND FL PROTEINS

The KL and FL proteins are structurally similar to each other (as described below)48-50 and to M-CSF.78 The primary translation product of the KL gene is a type 1 transmembrane protein, ie, the N-terminus of the protein is located outside of the cell. This protein is biologically active on the cell surface.79 The murine and human KL proteins are each 273 amino acids in length, with a 25 amino acid leader, a 185 amino acid extracellular domain, a 27 amino acid transmembrane domain, and a 36 amino acid cytoplasmic tail.

The murine32,79 KL protein has four potential sites for N-linked sugar addition; the human protein has five. KL made by Buffalo rat liver cells is N-glycosylated in a heterogeneous fashion and probably contains O-linked sugars. Analysis of human KL produced by Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells shows that it is glycosylated in a somewhat different manner than the rat protein and that it also contains O-linked sugars.80

Circular dichroism spectra of KL shows that it has considerable secondary structure, including both α helical and β sheets.80 There are four cysteine residues that are conserved between KL, FL, and M-CSF. In the case of KL, these form two intramolecular disulfide bonds that establish the three-dimensional structure of the protein.81 Although KL forms homodimers in solution, they are not covalently linked.80 KL is thus different from M-CSF, which contains three intramolecular disulfide bonds and an unpaired cysteine residue that forms an intermolecular disulfide bond.82 Preliminary data suggest that FL also contains three intramolecular disulfide bonds and exists as a noncovalently linked homodimer (Rick Remmele, Immunex, Seattle, WA; unpublished observation).

Mutagenesis studies of mouse and human KL have identified a core region that is required for biological activity; this region constitutes the major portion of the extracellular domain and encompasses all four of the cysteine residues conserved between KL, FL, and M-CSF.83,84 Neither the cytoplasmic, transmembrane, spacer, nor tether regions of KL (Fig 1) is required for biological activity. Similar studies on FL have yielded essentially identical results.85

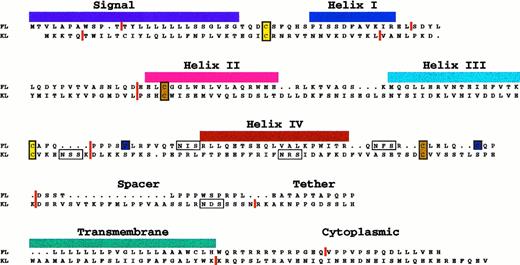

Sequence alignment of human FL and KL proteins. The figure illustrates that both colony-stimulating factors are type I transmembrane proteins with short cytoplasmic domains; both are likely to be four helix bundle proteins (based on x-ray crystallography data in the case of M-CSF82). The approximate positions of the four helices are shown. The vertical red lines show the locations of introns (to the nearest amino acid) within the genes33,93,95,104 and illustrate their common genomic structure and ancestral origin. Conserved cysteine residues are shaded in color to reflect the formation of proposed intramolecular disulfide bonds (3 in the case of FL and 2 in the case of KL). Possible sites for N-linked glycosylation are boxed. The alignment is based on the one originally proposed by Bazan78 for KL and M-CSF.

Sequence alignment of human FL and KL proteins. The figure illustrates that both colony-stimulating factors are type I transmembrane proteins with short cytoplasmic domains; both are likely to be four helix bundle proteins (based on x-ray crystallography data in the case of M-CSF82). The approximate positions of the four helices are shown. The vertical red lines show the locations of introns (to the nearest amino acid) within the genes33,93,95,104 and illustrate their common genomic structure and ancestral origin. Conserved cysteine residues are shaded in color to reflect the formation of proposed intramolecular disulfide bonds (3 in the case of FL and 2 in the case of KL). Possible sites for N-linked glycosylation are boxed. The alignment is based on the one originally proposed by Bazan78 for KL and M-CSF.

The primary translation product of the FL gene is also a type 1 transmembrane protein. The mouse and human proteins contain 231 and 235 amino acids, respectively. The first 27 (mouse) or 26 (human) amino acids constitute a signal peptide that is absent from the mature protein, followed by a 161 (mouse) or 156 (human) amino acid extracellular domain, a 22 (mouse) or 23 (human) amino acid transmembrane domain, and a 21 (mouse) or 30 (human) amino acid cytoplasmic tail. The cytoplasmic domains of murine and human FL are only 52% identical and are much more divergent than the cytoplasmic domains of murine and human KL (92% identical). Why the cytoplasmic domains of mouse and human FL are so much more divergent in sequence than the cytoplasmic domains of mouse and human KL is unknown. The mouse and human FL proteins each contain two potential sites for N-linked glycosylation. The human FL protein contains N-linked sugars (Claudia Jochheim, Immunex; unpublished observation).

KL AND FL ISOFORMS

The mature mouse and human KL proteins (from which the amino acid signal sequence has been cleaved) undergo proteolytic cleavage to generate a soluble, biologically active, 164-165 amino acid protein.32,33,79,86 The primary site for proteolytic cleavage is encoded within exon six33; however, mutagenesis experiments have shown that there is a secondary proteolytic cleavage site just upstream of the transmembrane region within exon 7.87 This secondary site is used only if the primary site is missing, which can occur by splicing out the sixth exon.79,88 89

Splicing has been suggested to be a method of regulating the generation of soluble versus membrane-bound forms of the protein. Alternative splicing of the sixth exon of the KL gene has been reported in both mouse and human cells.40,79,88,90,91 The cell-bound form of KL appears to be required for normal development in mice since a mutation (Sld) that eliminates the membrane-bound form of the factor, but still makes a biologically active soluble form, results in developmental abnormalities.88,92 Huang et al90 showed that there is tissue-specific expression of the different isoforms. The physiologic significance of these altered isoform ratios is unknown but presumably reflects the capacity of each tissue to produce a form of KL that is capable of interacting with specific c-kit-expressing cells.

It is unclear what regulates the proteolytic cleavage of KL, and what, if any, the physiologic effects of this process are. The protease responsible for cleavage of KL has not been identified, and it is unknown if it is the same protease that generates soluble, biologically active forms of M-CSF and FL.48,49 93

Multiple isoforms of both mouse and human FL have been identified by analysis of multiple cDNA clones and PCR.48-50,94 The biological significance of these isoforms is presently unknown. The predominant isoform of human FL is the transmembrane protein that is biologically active on the cell surface.48-50 This isoform is also found in the mouse, although it is not the most abundant isoform in that species (see below). The transmembrane FL protein can be proteolytically cleaved to generate a soluble form of the protein that is also biologically active.48 Neither the protease responsible for this cleavage nor the exact site in the FL amino acid sequence where cleavage occurs has been identified.

The most abundant isoform of murine FL95 is an alternative, 220 amino acid form that is membrane bound, but is not a transmembrane protein.49,94 This form arises due to a failure to splice an intron from the mRNA. This leads to a change in the reading frame, which terminates in a stretch of hydrophobic amino acids that serve to anchor the protein in the membrane.50 This isoform is missing the spacer and tether regions that contain the proteolytic cleavage site seen in the transmembrane isoform. As a result, this membrane-associated isoform is resistant to proteolytic cleavage,94 although it is biologically active on the cell surface. This isoform has not been identified in any human FL cDNAs examined.

A third FL isoform identified in mouse94 and human95 tissues arises because of an alternatively spliced sixth exon. This exon introduces a stop codon near the end of the extracellular domain and thereby generates a soluble, biologically active protein that appears to be relatively rare compared with other isoforms.95 Another method of generating soluble FL in the human is to splice out the transmembrane domain,50 but the relative abundance of this isoform has not been quantitated.

There is a difference between KL and FL in regard to their alternatively spliced sixth exons. The amino acids in exon 6 of mouse and human KL are nearly identical, whereas those of mouse and human FL have virtually no homology.95 In the case of KL, the sixth exon is normally part of the transmembrane protein and contains the proteolytic cleavage site. In the case of FL, it is not a part of the transmembrane protein; introduction of the sixth exon results in the generation of a soluble protein due to a shift in the reading frame. Thus, evolution has made two different uses of the sixth exon of KL and FL, allowing the generation of a soluble protein by different mechanisms.

STRUCTURE OF THE GENOMIC LOCI ENCODING THE c-kit AND Flt3 RECEPTORS

The genomic loci encoding the c-kit, flt3, and c-fms receptors share overall conservation of exon size, number, sequence, and exon/intron boundary positions,96 and these genes have likely arisen from a common ancestral gene. The genomic loci encoding the mouse97 and human98-100 c-kit receptors show clear evidence of evolutionary conservation. The coding region of the c-kitreceptor encompasses 21 exons, and both the mouse and human loci span more than 70 kb of genomic sequence.

STRUCTURE OF KL AND FL GENOMIC LOCI

The genomic locus encoding KL has been cloned from the human,33 rat,33 and mouse.103 The human KL locus is more than 50 kb in length (Vann Parker, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA; personal communication) and consists of eight exons that contain the entire coding region of the protein. The intron:exon boundaries identified within the rat, human, and murine genes occur at identical positions. In the case of the mouse protein, a ninth exon is present and encodes the C-terminal end of the cytoplasmic domain.103

The genomic loci encompassing the coding regions of mouse and human FL are approximately 4.0 kb and 5.9 kb, respectively; the coding region comprises 8 exons.95 The human FL locus is thus significantly smaller than the human KL locus. The sizes of the individual FL exons are well conserved between species,95although the intron sizes are much more variable.

The genomic locus encoding M-CSF also contains eight exons.104 A comparison of exon sizes between FL, KL, and M-CSF shows that identically numbered exons are similar in size in all three proteins.95 If the sizes of the exons are taken as a measure of overall relatedness, then M-CSF and KL are more closely related to each other than they are to FL. For example, the sizes of exons 3 and 4 are identical between M-CSF and KL, but are not the same as the corresponding exons in FL. The location of the introns in the three genes are also fairly well conserved, indicating that these proteins are probably ancestrally related.

CHROMOSOMAL LOCATION OF c-kit AND Flt3 RECEPTORS

The murine c-kit locus is located in the D-E region of mouse chromosome 511,12 near two other tyrosine kinase receptors (PDGF A and flk-1/KDR). The murine flt3 receptor gene is also on chromosome 5, but at the G region.41 The flt3 receptor105 is located less than 350 kb from the murine flt tyrosine kinase receptor106 but is separated from the clustered c-kit, PDGF A, and flk-1/KDR receptors.

The human c-kit locus is on the centromeric region of chromosome 4, in the area of 4q31-34,534q11-21,54 and 4q11-12.107 The gene encoding the human flt3 receptor maps to chromosome 13q12,41 again near the flt receptor locus. The flt3 and flt genes are linked105 in a head to tail fashion and are separated by about 150 kb.101

CHROMOSOMAL LOCATION OF KL AND FL GENES

The KL gene is, as expected, encoded on mouse chromosome 10 and is deleted in some, but not all, Sl alleles.32,35,36The FL gene maps to the proximal portion of mouse chromosome 7.94

The gene encoding human KL has been mapped to chromosome 12q22-2440 and 12q14.3-qter108 in a region that is syntenic with mouse chromosome 10. The human FL gene maps to chromosome 19q13.3-13.4,94 109 which is syntenic with mouse chromosome 7. The chromosomal locations of KL, FL, M-CSF, and their receptors are summarized in Table 1.

Chromosomal Locations of the c-kit,c-fms, and Flt3 Receptors and Their Ligands

| . | Mouse . | Human . |

|---|---|---|

| Receptors | ||

| Flt3 | 5G | 13q12 |

| c-kit | 5D-E | 4q11-34 |

| c-fms | 18 | 5q32-33 |

| Ligands | ||

| FL | 7 | 19q13.3-13.4 |

| KL | 10 | 12q14.3-qter |

| M-CSF | 3 | 1p13-21 |

| . | Mouse . | Human . |

|---|---|---|

| Receptors | ||

| Flt3 | 5G | 13q12 |

| c-kit | 5D-E | 4q11-34 |

| c-fms | 18 | 5q32-33 |

| Ligands | ||

| FL | 7 | 19q13.3-13.4 |

| KL | 10 | 12q14.3-qter |

| M-CSF | 3 | 1p13-21 |

GENETIC ALTERATIONS IN c-kit AND KL GENES

The exact defect in the c-kit receptor has now been identified at the molecular level for a number of alleles of the Wlocus.24-28 Most of the alleles result from point mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor; these changes decrease the tyrosine-phosphorylating activity of the protein. However, in several cases, the mutations appear to be of a regulatory instead of a structural nature and result in reduced expression of the c-kitreceptor.

There is a rare, autosomal dominant genetic disease in humans known as piebald trait. Affected individuals have a white forelock and large, nonpigmented patches on the chest and/or other areas. All cases of piebald trait that have been molecularly analyzed result from missense or frameshift mutations in the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor (Ezoe110 and references therein). Affected individuals are heterozygous for defects in the c-kit protein; the dominant nature of the trait reflects the dominant-negative effects of the mutant c-kit allele. The dominant-negative effects of these mutations are thought to result because receptor dimerization is required for proper biological function.

Because pigmentation defects in W and Sl mice are often indistinguishable, it would be reasonable to expect that at least some cases of piebald trait in humans would arise from mutations in the KL gene, ie, from a defect in the ligand instead of the receptor. However, no defects in the KL gene have been reported in piebald humans. Piebald trait thus represents the human homologue of the W mutation in mice.

Mutations at the Steel locus35 have occurred spontaneously or have been induced by chemical mutagenesis, x-ray irradiation, or transgene insertion.111 In addition to theSld mutation (see above), the molecular defect responsible for three other Sl mutations has been identified. In the Sl17H mutation,103 the cytoplasmic tail of KL is altered as a result of a splicing defect; in contrast, the Slcon and Slpanmutations are of a regulatory nature and result in altered, tissue-specific expression of mRNAs encoding KL.112

GENETIC ALTERATIONS IN Flt3 RECEPTOR AND FL GENES

In contrast to the well-described mutations in the c-kitreceptor and its ligand (see above), there are no reports of any genetic defects associated with either the flt3 receptor or its ligand.

As described above, FL maps to human chromosome 19q13.3. Trisomy 19 is strongly associated with myeloid malignancies.113 However, whether overexpression of FL plays a role in the increased incidence of leukemia in trisomy 19 remains to be determined.

EXPRESSION OF KL AND FL IN MOUSE AND HUMAN HEMATOPOIETIC TISSUES

The expression of the c-kit and flt3 receptors, and not their ligands, is the key to understanding the function of these growth factors. Numerous studies have shown that both KL and FL are widely expressed in different tissues, in contrast to their receptors, which are expressed on a more limited number of cells, especially in the case of flt3. KL is widely expressed during embryogenesis,114-116 suggesting that KL may affect the growth, survival, and/or differentiation of cells in addition to the three lineages (hematopoietic cells, germ cells, and melanocytes) shown to be affected in both W and Slmutant mice. Cells expressing KL are frequently contiguous with cells expressing c-kit, ie, ligand and receptor expression are complementary. KL is expressed on stromal cells,117,118fibroblast,26,79,119 endothelial cells,117visceral yolk sac,115 and other places.

FL, like KL, is widely expressed in both murine and human tissues.49,50,94 Highest levels of FL mRNA on human tissue Northern blots are in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, but the ligand is also expressed in almost every tissue that has been examined.48-50 Mouse developmental in situ hybridization studies have not yet been performed with FL, although it would be interesting to see how the distribution of FL would compare with flt3 receptor.120

EXPRESSION OF c-kit AND Flt3 RECEPTORS ON HEMATOPOIETIC CELL LINES

Expression of the c-kit receptor has been extensively surveyed on mouse and human hematopoietic cell lines (Table 2). It is seen on only a small percentage of myeloid and myeloblastic cell lines.121-124In contrast, the majority of erythroid and erythroleukemia cell lines express c-kit,121-123,125 as do virtually all megakaryocytic cell lines.121,123,125 Mast cell lines generally express c-kit.51,126-128 In contrast, expression of c-kit is generally not seen on lymphoid leukemia cell lines (including pre-B, B, and T cells),121,123,125 on B-cell or T-cell lymphoma cell lines,121,122,125 or on myeloma cell lines.121

Expression of c-kit and Flt3 Receptors on Murine and Human Cell Lines

| . | c-kit . | Flt3 . |

|---|---|---|

| Myeloid | Few positive | Mostly positive* |

| Monocytic | Few | About 50% |

| Erythroid | Most | Few |

| Megakaryocytic | Most | Few |

| Mast cell | All | None |

| Lymphoid | ||

| Pro-B | None | Most |

| Pre-B | None | Most* |

| B | None | Few |

| T | None | Few |

| Mature NK | ND | None |

| Lymphomas | None | About 25% |

| Myeloma | None | None |

| . | c-kit . | Flt3 . |

|---|---|---|

| Myeloid | Few positive | Mostly positive* |

| Monocytic | Few | About 50% |

| Erythroid | Most | Few |

| Megakaryocytic | Most | Few |

| Mast cell | All | None |

| Lymphoid | ||

| Pro-B | None | Most |

| Pre-B | None | Most* |

| B | None | Few |

| T | None | Few |

| Mature NK | ND | None |

| Lymphomas | None | About 25% |

| Myeloma | None | None |

Results tabulated from a large number of reports. For individual references, see the sections of this report detailing the expression patterns for each of these receptors.

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

Different expression patterns have been reported on mouse versus human cells; see text for details.

Flt3 receptor expression on mouse and human cell lines is quite different from that of c-kit. No flt3 expression is seen on any of the mouse myeloid, macrophage, erythroid, megakaryocyte, or mast cell lines examined46,129 or most early mouse B-cell lines, but it has been reported on several mature B-cell lines.129This lack of expression is different from what is seen on most human pre-B-cell lines, which do express flt3 receptor.123,130 In addition, flt3 expression has been seen on only one mouse pro-T cell line, but not on any T-cell lines.46 129

A number of studies have been published that show expression of flt3 receptor on a limited range of human cell lines. The flt3 receptor is found on a high percentage of human myeloid and monocytic cell lines,123,129,130 in contrast to mouse cell lines.46,129 No flt3 expression is seen on myeloma cell lines,129,130 and only a few megakaryocytic cell lines are positive.123,129,130 All erythroid and erythroblastic cell lines are flt3 negative as well.129 130

EXPRESSION OF c-kit AND Flt3 RECEPTORS ON PRIMARY HUMAN LEUKEMIAS

Both the c-kit and flt3 receptors are frequently seen on acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) blasts. The c-kit protein is expressed on blast cells obtained from a high percentage of patients with AML from all French-American-British (FAB) subtypes.61,124,131-139 Receptor levels on AML blast cells are variable, but in general are similar to or less than c-kitlevels on normal stem and progenitor cells.140

Expression of the flt3 receptor in primary leukemias has also been investigated and recently reviewed.141 As with c-kit, the majority of adult AML samples from all FAB classes are positive for flt3 receptor expression.57 142-146

Among lymphoid leukemias, little or no expression of c-kit is observed on blast cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).133,143 c-kit is expressed on Reed-Sternberg cells in about half of Hodgkin's disease patients as well as on some anaplastic large-cell lymphoma samples.147

All B-lineage ALL samples examined are flt3 receptor positive,142-144 as are most hybrid (also known as mixed or biphenotypic) leukemia samples.144 The greatest variability reported in flt3 receptor expression is on T-lineage ALL, which have been reported to be all negative,142 have a small percentage that are positive,143 or have about half of the samples positive.144 In contrast, both T-cell and B-cell lymphomas are negative for flt3 receptor expression.144Tandem in-frame duplications in the juxtamembrane region of the human flt3 receptor have been reported to be associated with both leukocytosis148 and leukemic transformation.149

The c-kit receptor is expressed on a majority of samples from chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) patients in blast crisis134,150 and at least some samples of chronic phase CML138 and CML in blast transition.151 In contrast, almost all chronic-phase or accelerated-phase CML samples are negative for flt3 receptor expression.143,144 However, about two thirds of the samples from CML patients in blast crisis are flt3 receptor positive.143 144

RESPONSIVENESS OF PRIMARY LEUKEMIA CELLS TO KL AND FL

AML.

Numerous studies have been performed on human leukemia samples to determine whether the cells proliferate in response to KL, FL, or other growth factors, although a lack of proliferation should not necessarily be considered negative expression. For example, a growth factor could drive differentiation or inhibit apoptosis; in fact, both KL152 and FL153 have been shown to have this latter effect. In the case of nonproliferative cells, the cells may be truly nonresponsive or may be producing endogenous ligand, and thus are refractory to exogenously added growth factor.

c-kit receptor expression is variable among AML FAB subtypes and does not predict responsiveness to KL.145 The majority of AML samples proliferate in response to KL.61,131,137,154,155 Many of these studies show that KL synergizes with other cytokines to enhance the proliferation of leukemic blast cells. Some AML cell lines express KL in addition to c-kit,140,156 suggesting that an autocrine loop may play a role in the transformation of these cells. However, the low level of KL expression on some AML cells has led one group to conclude that a c-kit and KL autocrine cycle is not common in AML.140

Whether flt3 receptor or its ligand play a causal role in the development of human leukemias has not been determined. A large percentage of AML cells from children142 and adults145,146 proliferate (as measured by both [3H]-thymidine incorporation or colony formation) in response to FL. Within age groups (children or adults), some FAB subtypes show a greater response compared with others.142 146 It is unclear whether there is a difference in the FL responsiveness of flt3 receptor-positive AML samples of different FAB subtypes from children and adults because not enough samples of each FAB subtype have been analyzed.

Primary AML samples that proliferate in response to FL also frequently proliferate in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), and KL, and additive or synergistic responses are observed. Some AML cells are therefore similar to normal hematopoietic progenitor cells in that both show synergistic responses to FL in combination with other cytokines. Many of the AML samples that do not proliferate in response to FL do proliferate in response to other cytokines,142 indicating that the cells do not lack a general capacity to proliferate. In summary, flt3 receptor expression on AML samples is not predictive of FL responsiveness, just as c-kit expression is not predictive of KL responsiveness.

CML.

KL can weakly stimulate the proliferation of CML blast cells on its own and strongly stimulate them in the presence of IL-3 and/or GM-CSF.138 Culturing of bone marrow (BM) cells from CML patients in the presence of KL favors the growth of malignant progenitor cells.157 In contrast, preliminary results suggest that FL favors the outgrowth of benign progenitors from 5-FU-treated CD34+ CML BM cells at the expense of malignant cells158 and that FL generates a significantly greater percentage of normal progenitors (Philadelphia chromosome-negative cells) compared with KL.

ALL.

Because c-kit is not generally expressed on ALL cells,124,133,134,139 the capacity of these cells to proliferate in response to KL has not been examined. As mentioned above, all B-lineage ALL and some T-lineage ALL samples express flt3 receptor. However, only a small percentage of B-lineage ALL samples proliferate in response to FL.142

In one study, pediatric T-lineage ALL samples did not proliferate in response to FL, but none of these samples was positive for flt3 expression.142 In a separate study on a variety of ALLs, several flt3 receptor-positive samples proliferated in FL.159 However, the majority of samples failed to proliferate in FL, even though they were flt3 receptor positive.159 Flt3 receptor expression is therefore not predictive for proliferation of ALL cells to FL in vitro.

EXPRESSION AND FUNCTION OF c-kit AND Flt3 IN THE HEMATOPOIETIC HIERARCHY

Studies of cytokine receptor expression have proven valuable in pinpointing where specific ligand-receptor pairs have biological activities. Not only can such studies identify cell types in which a specific receptor might be important, they also allow functional characterization of distinct cell populations separated based on various levels of receptor expression. The expression of c-kitand flt3 in the hematopoietic system has been studied in detail, and in the following sections we review the findings of flt3 and c-kitexpression on various cell types (summarized in Fig 2), followed by the in vitro biological effects (summarized in Table 3) of FL and KL on the same cell types. It is important to emphasize that the extensive c-kitand flt3 expression studies to be described have inherent limitations. Most expression studies have been performed by flow cytometric evaluation of cell-surface c-kit and flt3 expression. Because flow cytometry has a rather high detection limit (∼500 molecules/cell), so- called c-kit− and flt3− populations might prove to express low levels of c-kit and flt3, respectively. On the other hand, reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) detection of c-kitand flt3 mRNA has much greater sensitivity, but unless performed at the single-cell level does not provide a quantitative measurement of c-kit+ and flt3+ cells. Thus, a minor contaminating (nonrelevant) cell type might account for detected expression (particularly relevant for heterogenous primary cell populations).

c-kit and Flt3 expression in the hematopoietic hierarchy. The figure indicates expression of c-kit (red, upper symbol on side of each cell) and flt3 (green, lower symbol on side of each cell) on various classes of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells as well as mature blood cells, as described in the text. Because most hematopoietic cell populations are heterogeneous and hard to purify, it is not possible to exclude c-kit and/or flt3 expression on a minority of cells in the different cell populations. Therefore, the figure illustrates the c-kit and flt3 receptor status on the majority of cells within a specific population, based on studies of receptor expression and/or functional studies. As discussed in the text, the proposed hierarchy of pluripotent stem cells is based solely on different levels of c-kit and flt3 expression and does not take into account other stem cell antigens/characteristics, which are likely to uncover additional heterogeneity. Symbols: (−) most/all cells appear to lack c-kit or flt3 expression; (+) most/all cells appear to express c-kit or flt3; (+/−) the cell type appears to consist of significant receptor-positive as well as receptor-negative populations; (?) sufficient expression or functional data not available; (high and low) cell populations have been separated based on high and low levels of c-kit expression. Abbreviations: BFU, burst-forming units; CFU, colony-forming units; E, erythroid; Mk, mega karyocyte; G, neutrophilic progenitor; M, monocyte/macrophage; DC, dendritic cell; Baso, basophil; RBC, red blood cell; NK, natural killer cell.

c-kit and Flt3 expression in the hematopoietic hierarchy. The figure indicates expression of c-kit (red, upper symbol on side of each cell) and flt3 (green, lower symbol on side of each cell) on various classes of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells as well as mature blood cells, as described in the text. Because most hematopoietic cell populations are heterogeneous and hard to purify, it is not possible to exclude c-kit and/or flt3 expression on a minority of cells in the different cell populations. Therefore, the figure illustrates the c-kit and flt3 receptor status on the majority of cells within a specific population, based on studies of receptor expression and/or functional studies. As discussed in the text, the proposed hierarchy of pluripotent stem cells is based solely on different levels of c-kit and flt3 expression and does not take into account other stem cell antigens/characteristics, which are likely to uncover additional heterogeneity. Symbols: (−) most/all cells appear to lack c-kit or flt3 expression; (+) most/all cells appear to express c-kit or flt3; (+/−) the cell type appears to consist of significant receptor-positive as well as receptor-negative populations; (?) sufficient expression or functional data not available; (high and low) cell populations have been separated based on high and low levels of c-kit expression. Abbreviations: BFU, burst-forming units; CFU, colony-forming units; E, erythroid; Mk, mega karyocyte; G, neutrophilic progenitor; M, monocyte/macrophage; DC, dendritic cell; Baso, basophil; RBC, red blood cell; NK, natural killer cell.

In Vitro Effects of KL and FL in the Murine and Human Hematopoietic System

| Cell Type . | Response . | KL . | FL . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive progenitors/candidate stem cells | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Viability | + | + | |

| Adhesion | + | ND | |

| Erythroid progenitors | |||

| BFU-E | Growth | Synergy | − |

| Adhesion | + | − | |

| CFU-E | Growth | + | − |

| Myeloid (GM) progenitors | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Viability | + | + | |

| Adhesion | + | ND | |

| Megakaryocytopoiesis | |||

| BFU-Mk/CFU-Mk | Growth | + | + |

| Mk maturation | + | − | |

| Mast cells | Growth | + | − |

| Maturation | + | − | |

| Adhesion | + | − | |

| Migration | + | − | |

| Activation | + | − | |

| B lymphopoiesis | |||

| Murine stem cells | Growth/ commitment | Weak | Strong |

| Murine pro-B cells | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Human pro-B cells | Growth | − | Synergy |

| T lymphopoiesis | |||

| Murine pro-T cells | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Human pro-T cells | Stromadependent growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| NK cells | |||

| NK cell progenitors | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| NK cells | Growth | Synergy | ND |

| Viability | + | ND | |

| Dendritic cells | |||

| DC progenitors | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Cell Type . | Response . | KL . | FL . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive progenitors/candidate stem cells | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Viability | + | + | |

| Adhesion | + | ND | |

| Erythroid progenitors | |||

| BFU-E | Growth | Synergy | − |

| Adhesion | + | − | |

| CFU-E | Growth | + | − |

| Myeloid (GM) progenitors | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Viability | + | + | |

| Adhesion | + | ND | |

| Megakaryocytopoiesis | |||

| BFU-Mk/CFU-Mk | Growth | + | + |

| Mk maturation | + | − | |

| Mast cells | Growth | + | − |

| Maturation | + | − | |

| Adhesion | + | − | |

| Migration | + | − | |

| Activation | + | − | |

| B lymphopoiesis | |||

| Murine stem cells | Growth/ commitment | Weak | Strong |

| Murine pro-B cells | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Human pro-B cells | Growth | − | Synergy |

| T lymphopoiesis | |||

| Murine pro-T cells | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| Human pro-T cells | Stromadependent growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| NK cells | |||

| NK cell progenitors | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

| NK cells | Growth | Synergy | ND |

| Viability | + | ND | |

| Dendritic cells | |||

| DC progenitors | Growth | Synergy | Synergy |

Cell types or responses in which neither KL nor FL are known to have an effect are not listed.

Abbreviations: −, no effect found on indicated response (in some cases not specifically investigated but cell type lacks receptor for indicated ligand); +, stimulatory effect of ligand alone on indicated response; synergy, effect predominantly through synergistic interaction with other cytokines; ND, not determined.

EXPRESSION OF c-kit AND Flt3 ON MATURE BLOOD CELLS

c-kit and flt3 expression in the hematopoietic system appear predominantly restricted to the progenitor/stem cell compartment (outlined in the following sections). However, some differentiated blood cells also express these receptors (Fig 2).

c-kit is expressed on primary mast cells as well as mast cell lines and primary neoplastic mast cells.160 In addition, c-kit is constitutively activated in a number of mast cell tumor lines (mastocytomas),127,161 but mast cells do not express flt3.128

There are other differentiated hematopoietic cells that express c-kit and/or flt3, although the functional significance is less clear. In mouse BM, very low levels of c-kit can be detected on promyelocytes and myelocytes, but not on neutrophils.162 Approximately 50% of murine BM eosinophils and monocytes express low levels of c-kit.162 Seven percent of lymphocytes in murine BM express high levels of c-kit.162 However, still other studies suggest that mature B and T cells do not express c-kit; therefore, this small fraction of c-kit+ cells might represent B- and T-cell precursors/progenitors.163-165

Similar studies have revealed that flt3 expression in murine BM is restricted to blast cells, monocytes, and a small fraction of lymphocytes.166 Nucleated murine erythroid cells lack both c-kit and flt3 expression.162,166 Early murine megakaryocytes (stage I and II) express c-kit, whereas the most mature (stage III) megakaryocytes appear to be c-kit−.167 Also, human megakaryocytes express c-kit,61,168 but not flt3.169 In addition, activated but not resting platelets express c-kit.170

Initial studies indicated that flt3 mRNA is expressed by murine B and T cells from thymus, spleen, and peripheral blood.18 However, several later studies of mature murine B and T cells suggest that these do not express flt3.166 171 Thus, the initial findings potentially were due to a small fraction of contaminating flt3+ cells, such as more primitive B- and T-cell progenitors.

Peripheral human blood cells contain less than 0.1% c-kit+ cells, suggesting that very few mature human blood cells express c-kit.172-174 c-kit is constitutively expressed on a small subset of resting human NK cells in peripheral blood that are characterized by high CD56 expression, whereas c-kit is not expressed on the larger fraction of more differentiated NK cells with low CD56 expression.175 These c-kit+ NK cells appear to be the only mature, resting lymphocytes that constitutively express c-kit.

No expression of flt3 mRNA has been reported on mature lympohematopoietic cells fractionated from human peripheral blood17 or B cells, T cells, monocytes, or granulocytes.144 However, in other studies, monocytes and granulocytes have been shown as weakly positive at the mRNA and cell-surface level.16 176

RESPONSE OF MAST CELLS TO KL, BUT NOT FL

The effects of KL on mast cell populations have been extensively reviewed6 and will be only briefly summarized here. KL regulates the migration, maturation, proliferation, and activation of mast cells in vivo.6 Injection of recombinant KL into rodents,86,177 primates,178 or humans179 results in an increase in mast cells at both the site of injection and at distant sites. Treatment of rats with KL generates both connective tissue mast cells and mucosal mast cells.177 Animals treated with KL generally do not appear to suffer from serious adverse events despite the large-scale expansion of mast cells in vivo.178 However, at least one study has shown that KL administration to mice leads to degranulation of mast cells in the lungs, which leads to acute respiratory distress.180 The effects of KL on mast cells may have a significant impact on the clinical potential of this molecule for humans.179,181 182

COMMITTED MYELOID PROGENITOR CELLS ARE c-kit+Flt3+ OR c-kit+Flt3−, WHEREAS EARLY ERYTHROID PROGENITOR CELLS APPEAR TO BE ONLY c-kit+Flt3−

Half of c-kit+ murine BM cells coexpress lineage-specific cell surface antigens such as GR-1 and MAC-1 (Lin+), characteristic of cells committed to the myeloid lineage, whereas the remaining half express higher levels of c-kit and are Lin−, suggesting that uncommitted progenitor cells might express higher levels of c-kit than those committed to the myeloid lineage.183 Indeed, murine in vitro clonogenic progenitor cells committed to the myeloid lineage and colony-forming units-spleen (CFU-S) progenitors are almost completely depleted in c-kit− BM cells, showing that most, if not all, clonogenic myeloid progenitor cells express c-kit.183-188

Most c-kit+ human BM and fetal liver cells express the progenitor-associated CD34 antigen,172-174 suggesting that overlapping (but not identical) populations each express these two progenitor cell antigens. c-kit+ human BM and fetal liver cells are highly enriched and contain all or most in vitro clonogenic progenitor cells with a myeloid (granulocyte/monocyte), megakaryocytic, and/or erythroid potential.172-174 189

CD34highCD64+ cells, which are virtually a pure population of human GM progenitor cells, express high levels of c-kit, whereas the more mature CD34lowCD64+ cells express lower levels of c-kit,190 suggesting downregulation of c-kit expression during GM differentiation. Similarly, erythroid progenitor cells (CD34highCD64−CD71high and CD34lowCD64−CD71high) also express high levels of c-kit.190 Although some studies have suggested that a subclass of mature erythroid progenitor cells (colony-forming units-erythroid [CFU-E]) might not be KL-responsive, c-kit expression has been demonstrated on human CFU-E and erythroblasts.174 The vast majority of human megakaryocyte progenitor cells (burst-forming unit-megakaryocyte [BFU-Mk] as well as colony-forming unit-megakaryocyte [CFU-Mk]) are also c-kit+.191

Whereas almost 90% of murine BM blast cells express c-kit,162 flt3 expression is restricted to 30% of murine BM blast cells.166 The majority of lineage-restricted murine myeloid and erythroid BM progenitor cells are Lin−Sca-1− and express c-kit.188 However, less than half of these Lin−Sca-1−c-kit+progenitors express flt3.166

More than 60% of flt3+ human BM cells coexpress CD33, a myeloid cell-surface antigen, suggesting that flt3 might be expressed on subsets of myeloid progenitor and/or mature cells.57 Most human CD34+ BM and cord blood cells express flt3, and most GM progenitors express flt3, whereas CD34+flt3+ cells are depleted in erythroid progenitors.176 The majority of CD34+c-kit+ BM and cord blood cells coexpress flt3, but a significant (10% to 25%) population is flt3−.

Flt3 appears to be shut off before erythroid differentiation and gradually downregulated during GM differentiation.192 In contrast, c-kit expression is gradually downregulated during both erythroid and GM differentiation.192 Thus, flt3 appears to be expressed on subpopulations of myeloid (GM) progenitor cells, but not on erythroid progenitor cells.

Myeloid-derived dendritic cell (DC) progenitors appear to express c-kit and flt3, because they respond to KL and FL in combination with other cytokines (see DC section for details). However, neither ligand has been shown to have effects on mature DC.193-196

ERYTHROID PROGENITOR CELLS: KEY ROLE OF KL AND ABSENCE OF FL RESPONSE

Besides the mast cell deficiency, the dominating hematopoietic defect resulting from severe mutations in the W or Sl loci is a macrocytic anemia.6,10 KL enhances the in vitro cloning frequency as well as the clonal size of murine79,197 and human33,172,174,198-200 erythroid progenitor cells. KL has its most potent growth promoting effects on early erythroid progenitor cells (BFU-E), whereas more mature progenitors (CFU-E) are less responsive to KL-stimulation.172-174,191 201

The effects of KL on the growth of BFU-E are predominantly synergistic and require costimulation with erythropoietin (EPO).79,172,174,197-200 However, KL can, in combination with IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor, promote EPO-independent growth of human BFU-E in vitro.202 Furthermore, c-kit might activate the EPO receptor by inducing its phosphorylation on tyrosine.203 KL also promotes the adhesion of human BFU-E to fibronectin.204

MEGAKARYOCYTE PROGENITOR CELLS: POTENT GROWTH-PROMOTING EFFECTS MEDIATED THROUGH c-kit BUT NOT Flt3

Although Sl/Sld mice have normal levels of platelets, their BM displays reduced numbers of mature megakaryocytes and megakaryocyte progenitor cells.209-211 Administration of KL to Sl/Sld mice not only reverses the macrocytic anemia, but results in enhanced platelet production.36 In vitro, KL enhances megakaryocyte progenitor cell cloning frequency and growth potential in combination with other cytokines, including GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, and IL-11.168,212-215 Whereas some studies have found little or no effect on megakaryocyte maturation and ploidy, others have suggested that KL can promote megakaryocyte maturation and ploidy,216and subsets of early megakaryocytes express c-kit.167

Thrombopoietin (TPO) is the primary regulator of megakaryocyte and platelet production,217 and KL appears to interact with TPO at two levels in the hematopoietic hierarchy. First, a synergistic interaction is observed on committed megakaryocyte progenitor cells, enhancing megakaryocyte production.217-221 In addition, KL and TPO interact synergistically on candidate murine and human stem cell populations to stimulate multilineage growth in vitro.222-226 Thus, the primary role of KL in platelet production might be through its interaction with TPO.

Unlike W/Wv andSl/Sld mice, flt3 knockout mice have not been reported to have any defects in megakaryocyte and platelet production,227 and FL alone or in combination with IL-3, KL, or TPO has no effect on in vitro growth of murine megakaryocyte progenitor cells.65 Similarly, FL has no effect on megakaryocyte ploidy by itself or in combination with TPO.65 In contrast, FL acts synergistically with TPO to enhance the growth of candidate murine stem cells.223

Some data suggest that FL might have effects on human megakaryocytopoiesis. Some megakaryocytic leukemic cell lines, as well as primary megakaryoblastic leukemic cells, express flt3, although less frequently than c-kit.65,123,130 In addition, studies of FL effects on primary BM cells have demonstrated effects on megakaryocyte formation.228 Unlike KL, FL has been reported to have no synergistic interaction with TPO on in vitro clonogenic growth of human megakaryocyte progenitor cells.169 Thus, the finding that FL and TPO synergistically promote prolonged megakaryocyte progenitor cell formation in long-term cultures of human CD34+ cord blood cells229 could result from a recruitment of primitive (uncommitted) progenitor cells that might subsequently become responsive to TPO alone.

EXPRESSION OF c-kit AND Flt3 ON LYMPHOID PROGENITORS AND PRECURSORS

About 25% of B220+ murine BM cells express c-kit, accounting for more than half of the total c-kit+cells.164 However, no BM cells (or fetal liver cells) expressing cytoplasmic μ coexpress c-kit, suggesting that c-kit expression is restricted to the earliest stages of B-cell progenitors, whereas the pre-B-cell and subsequent stages are c-kit−.163,164,230 231

Flt3 mRNA is expressed in early murine pre-pro and pro-B cells, whereas pre-B cells, as well as immature and mature B cells, are devoid of flt3 expression.171 A similar pattern of flt3 expression is seen at the cell surface of pro-B, pre-B, and mature B cells.166c-kit is also expressed at low levels on subsets of human pro-B cell progenitor cells (CD34+CD19+).173,189,190Twenty-five percent of BM CD34+CD19+ (pro-B cells) express flt3, as do subfractions of CD10+ and CD20+ B-cell precursors.176

c-kit is expressed at high levels on the most primitive subsets of murine fetal and adult thymocytes, including CD4−CD8−CD3−CD44+CD25+pro-T cells and more primitive CD4loCD8−CD3− thymocytes, the latter cells also having the potential to develop into B cells.165,232-235 When thymocytes develop into CD4−CD8−CD3−CD44−CD25+pre-T cells, they still express low levels of c-kit, which is lost in later stages of T-cell development.165

Like c-kit, flt3 expression is restricted to the most immature CD4−CD8− murine thymocytes, whereas more mature thymocytes expressing CD4 and/or CD8 are flt3−.19

Because human NK cell progenitor cells respond to KL or FL (see separate section), they most likely express c-kit and flt3. However, there is as yet no direct evidence for c-kit or flt3 expression on NK cell progenitor cells, and the few human NK cell lines examined lack flt3 expression.130 236

Multipotent lymphoid progenitor cells capable of producing DC express high levels of flt3.237 Because a DC-restricted lymphoid progenitor has not yet been identified, c-kit and flt3 expression on such a CFU-DC remains to be established.

EARLY B-CELL DEVELOPMENT: COEXPRESSION OF c-kit AND Flt3 AND APPARENT KEY ROLE OF Flt3/FL INTERACTION

Although no reduction in cells of the B-cell lineage has been reported in adult W mutant mice, embryonic mice deficient in c-kit or KL expression have reduced numbers of B-cell progenitor cells in fetal liver.238 Such a reduction could indicate a direct role of c-kit and its ligand in B lymphopoiesis or, alternatively, an indirect effect of a depleted pool of pluripotent stem cells and/or altered stromal cells in these mice.186

KL can synergize with IL-7 to promote stroma-independent growth of murine BM pro-B- and pre-B-cell progenitors unresponsive to IL-7 alone, whereas KL lacks proliferative activity on B220+cμ+ pre-B cells.33,118,239,240 One study found that KL in combination with IL-7 could promote development of pre-B cells and expression of μ-heavy chain118; other studies have not found KL plus IL-7 sufficient to allow differentiation of pro-B cells into pre-B cells in vitro, even though such pro-B cells coexpress c-kitand IL-7 receptors.231,239,240 Furthermore, a blocking antibody against c-kit inhibits the growth of murine pro-B cells cultured on stromal cells in the presence of IL-7, but has no effect on pre-B-cell differentiation supported by the same stroma cells.163,241,242 Similarly, KL in combination with IL-7 can replace the requirement for stroma to induce pro-B-cell proliferation, but not differentiation into pre-B cells.239In addition to its ability to promote growth of committed pro-B cells, KL in combination with IL-7 can stimulate stroma-independent B-cell progenitor cell development from candidate murine stem cells243-245 or from bipotent macrophage-B-cell progenitor cells.246

In vivo treatment of mice with a blocking antibody against c-kit results in an almost complete elimination of myeloid and primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells, leaving virtually no mature granulocytes and erythroblasts in the BM.164,183 However, the total number of BM cells are normal, of which the majority are B220+.164,183 A concomitant expansion in the number of pre-B-cell progenitor cells is observed,164,183suggesting that an interaction between c-kit and KL is not required for B-cell development in vivo. In support of this, W/Wstem cells are as efficient as wild-type stem cells at reconstituting BM B cells in RAG-2-deficient mice.247 Thus, unlike the critical role of c-kit/KL interaction in generation of the erythroid, myeloid, and T-cell lineages, c-kit-KL is not required for normal B-cell development in adult mice. The mechanism behind the intriguing observation that a c-kit antibody blocks the production of mature myeloid and erythroid progeny but enhances B-cell development remains unclear, although it appears to result from an indirect rather than a direct effect.

An important and distinct role of FL in early stages of B-cell development is supported by studies of flt3-deficient mice. These animals, unlike c-kit-deficient mice, have reduced numbers of pro-B cells in the BM, although the number of mature B cells is normal.227 These findings have also been confirmed in FL-deficient mice.248

FL promotes the in vitro growth of early B-cell progenitor cells in a pattern distinct from that of KL. Primitive (CD43+B220lowCD24−) B-cell progenitors in murine BM do not respond to either FL or IL-7 individually, but in combination the two cytokines induce a greater proliferative response than IL-7 plus KL.249 In contrast, more differentiated CD43+B220lowCD24+ B-cell progenitors fail to respond to FL, whereas KL enhances IL-7-induced proliferation, indicating that FL activity is restricted to an earlier stage of B-cell development than KL activity. Another important finding is the capacity of FL plus KL to promote the growth of CD43+B220lowCD24−B-cell progenitor cells in the absence of IL-7.249 This might help explain why IL-7 receptor-deficient mice have normal levels of these primitive B-cell progenitors, but dramatic reductions in more differentiated B-cell progenitors and mature B cells.250 It could also explain why mice with a combined deficiency in flt3 and c-kit have a more severe reduction in early B-cell progenitors than mice deficient in flt3 only.227

FL synergizes with IL-7 to enhance the production of B220+cells from B220+ as well as B220− murine BM cells.245 IL-7-independent B220+ cell development occurs in the presence of FL alone, but not KL alone, indicating a primary role of FL over KL in early murine B-cell development. Pro-B cells isolated from murine fetal liver also proliferate in response to either FL or KL in combination with IL-7, maintaining a population of early pro-B cells.251

Because the B-cell defect in flt3-deficient mice is restricted to a reduction in the most primitive B-cell progenitors, an essential role of flt3/FL might be to promote B-cell development from progenitor/stem cells not yet committed to the B-cell lineage. In support of this, FL and KL can each promote the growth of fetal liver and BM progenitor cells with a combined myeloid and lymphoid potential.251,252 FL and IL-7 synergize to enhance the growth of primitive murine Lin−Sca-1+ BM progenitors, resulting in production of almost exclusively pro-B cells, whereas KL plus IL-7 stimulate formation of 90% myeloid cells.252

Studies of the early stages of human B-cell growth have been hampered by the lack of optimized in vitro systems. Therefore, the potential roles of KL and FL in human B-cell development remain to be elucidated. A stimulatory effect of KL on committed human B-cell progenitors has been suggested,253 although stromal and IL-7-dependent early B lymphoid growth from BM or cord blood cells in vitro is neither stimulated by KL nor inhibited by a neutralizing anti-KL antibody.254-256 In contrast, FL in combination with IL-7 promotes stromal cell-independent growth of human fetal BM pro-B cells (CD34+CD19+), whereas KL has no effect.256

Although the precise roles of FL and KL in B lymphopoiesis remain to be determined, the available in vitro, in vivo, and knockout data suggest that flt3 and FL may be more critically involved in early B-cell development than c-kit and KL, perhaps identifying a physiologically important difference between KL and FL.

T-CELL PROGENITOR CELLS

In mice lacking functional c-kit expression, T-cell numbers in peripheral blood are normal,257 although a deficiency in fetal thymic development has been reported.258

One purified c-kit+ BM stem cell can reconstitute the thymus in more than 40% of sublethally irradiated mice, whereas c-kit− stem cells have little or no such ability.259 Although the BM population can produce myeloid/erythroid as well as T-cell progeny, thymus-derived c-kit+Lin−Thy-1lo cells appear to be lymphoid-restricted.260 Anti-c-kitantibodies completely block T-cell generation from BM, but not thymic cells, suggesting that T-cell generation from these primitive, lymphoid-committed stem cells in the thymus might not require signaling through c-kit.260

KL has little or no growth-promoting activity alone, but promotes IL-7-stimulated growth of primitive mouse CD4−CD8−CD3− thymocytes, but not CD4+CD8+ cells or single CD4+and CD8+ cells.234,261 Anti-c-kitantibodies dramatically inhibit in vitro fetal thymic T-cell production and differentiation from fetal liver progenitor cells.234Similarly, anti-c-kit antibodies reduce cell production and differentiation towards CD4+CD8+ cells in a reconstitution assay with fetal thymocytes into fetal thymus.232 This suggests that KL might be involved in promoting the growth and differentiation of immature thymocytes. IL-3 and IL-12 have been shown to synergize with KL to enhance the growth of primitive, but not more mature, thymocyte populations.235

T-cell numbers in peripheral blood are normal, but a reduction in early T-cell progenitors is seen postnatally in flt3-deficient mice, and flt3-deficient stem cells are impaired in their ability to reconstitute T cells in the thymus and peripheral blood.227

FL synergizes with IL-7 to stimulate the proliferation of unfractionated murine thymocytes, and a stimulatory effect can be seen in response to FL in the absence of IL-7.49 The most primitive CD4low thymic progenitor cells capable of generating multiple lymphoid lineages are growth stimulated by FL (in combination with IL-3, IL-6, and IL-7) more efficiently than with KL.262 In contrast, pro-T cells are more efficiently expanded with KL than FL, suggesting that FL might be more active than KL at an earlier stage of T-cell growth.262 In agreement with this, FL appears to preferentially promote self- renewal of CD4low cells in fetal thymic organ culture, whereas KL promotes early T-cell differentiation.262

Studies of cytokine effects on the regulation of human T-cell development have been difficult due to the lack of appropriate in vitro assays. However, KL enhances thymic stromal cell-supported production of human CD4+ and/or CD8+ cells from CD34+CD4−CD8− BM progenitor cells,263 whereas FL promotes IL-12-stimulated T-cell production from human CD34+ BM cells on thymic stromal layers.264

NK CELL PROGENITORS

c-kit is constitutively expressed on a small subset of resting human NK cells in peripheral blood characterized by high CD56 expression, but not on the larger fraction of more differentiated NK cells with low CD56 expression.175 These c-kitreceptors are functional because KL suppresses apoptosis, apparently through induction of bcl-2 expression, although it does not promote proliferation, differentiation, or cytotoxicity on its own.152,175 However, KL in combination with IL-2 promotes the growth, but not cytotoxicity, of this population of resting NK cells.175

KL enhances stroma-independent NK cell development from human BM progenitor cells stimulated by IL-2, IL-7, or IL-15 in vitro.265-267 An important regulatory role of flt3 and its ligand in NK cell development is supported by the finding that FL-deficient mice treated with poly IC or IL-15 are devoid of NK cell activity in the spleen.248 Furthermore, FL in combination with IL-15 promotes the expansion but not differentiation of CD3−CD56+ NK cells from human CD34+ progenitor cells.268

DC DEVELOPMENT: KEY ROLE OF FL

All DC express CD45 and arise from BM progenitor cells; evidence suggests that DC derive from myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells.269,270 Myeloid-derived DC can be generated in vitro from progenitor cells isolated from BM, mobilized peripheral blood, or cord blood; GM-CSF appears to play a primary role in promoting their production.269,270 A number of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-4, and KL, can enhance DC formation induced by GM-CSF.269,270 KL stimulates DC formation from human CD34+ BM and cord blood progenitor cells in combination with GM-CSF and TNF-α without affecting DC differentiation.193-195

FL increases the production of DC from CD34+ BM progenitor cells in combination with GM-CSF plus TNF plus IL-4.196This enhanced DC production is similar to that observed in response to KL, and when these two cytokines are combined, the effect is additive.196 As with KL, FL does not appear to affect the differentiation, but rather the production, of DC.196Production of DC from mobilized CD34+ peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) by GM-CSF and TNF-α is enhanced by KL and FL individually; combining them results in an additive response.271

KL or FL (in combination with other cytokines) promotes DC formation from uncommitted thymic precursors,272 but the identity and responsiveness to KL or FL of committed lymphoid-derived CFU-DC remains to be determined.

In vivo treatment of mice with FL results in a dramatic increase in the number of myeloid- and lymphoid-derived functional DC in BM, spleen, thymus, peripheral blood, gastrointestinal lymphoid tissues, and other tissues, indicating an absolute increase in functionally mature DC rather than a redistribution.273 In contrast, administration of KL, GM-CSF, or IL-4 to mice does not expand the number of DC in the spleen. A key role of FL in DC generation is further supported by reduced numbers of DC in FL-deficient mice.248

LONG-TERM RECONSTITUTING MURINE STEM CELLS ARE HETEROGENEOUS WITH REGARD TO c-kit AND Flt3 EXPRESSION

Many studies have suggested that most, if not all, pluripotent long-term reconstituting murine stem cells (LTRC; purified by various methods from BM, fetal liver, and the intra-embryonic aorta-gonad-mesonephros) express c-kit.184-188,274-276 Particularly noteworthy was a study in which a single Lin−Sca-1+CD34low/-c-kit+stem cell efficiently long-term reconstituted as much as one of five transplanted mice.277 In addition, cells with the same phenotype isolated from primary recipients were able to reconstitute secondary recipients.277 The corresponding c-kit− population was not investigated. Although these studies have clearly established that a large fraction and probably most LTRC are c-kit+, they do not necessarily rule out the possibility of a coexisting, and probably less frequent c-kit− LTRC, because the reconstitution assays might not have been optimal for detecting the LTRC activity of a (putative) c-kit− stem cell population.

In support of the potential existence of c-kit− stem cells, c-kit− murine BM cells without detectable c-kit expression but with LTRC, but no short-term reconstitution activity, have been identified.278 One study identified a minor but efficient c-kit− LTRC population (0.005% of BM cells).279 The absence of c-kit expression was verified at the cell surface as well as by RT-PCR. As few as 10 of these cells efficiently generated all blood cell lineages for the life span of the mice and showed extensive in vivo self-renewal ability, as assessed through serial transplantation. In contrast, as many as 1,000 of these cells showed no ability to promote radioprotection.279 This is in contrast to most c-kit+ LTRC (with the exception of CD34−/low c-kit+ stem cells277), which in general have been found to also be enriched in short-term reconstituting and radioprotective ability.184-186 188

The existence of an LTRC population with little or no c-kitexpression is also supported by another study280 in which candidate stem cells were subfractionated into c-kitlow and c-kit<low (no detectable cell surface expression but positive for c-kit mRNA) populations, representing 0.006% and 0.008% of the BM cells, respectively. These two populations did not differ in their capacity to provide donor long-term multilineage reconstitution in primary irradiated recipients. However, when BM from primary recipients was transplanted into secondary recipients, multilineage donor reconstitution could only be obtained from cells whose origin was c-kit<low stem cells.280 Tertiary recipients receiving cells derived from c-kit<lowstem cells were also efficiently reconstituted.280

Other investigators have subfractionated murine BM progenitor/stem cells based on different levels of c-kit expression. In one study, murine BM stem cells were isolated by counterflow centrifugal elutriation; subsequently fractionated into c-kitneg, c-kitdull, and c-kitbright subpopulations; and administered to unirradiated W/Wvrecipients.187 One hundred c-kitbrightcells were sufficient to repopulate lympho-hematopoiesis inW/Wv recipients, whereas as many as 2.5 × 104 c-kitdull or 5 × 105 c-kitneg cells had no LTRC activity.

Whereas the majority of BM colony-forming cells in normal mice are c-kitbright, most progenitors from 5-FU-treated mice are c-kitdull.281 Cells resistant to 5-FU represent predominantly dormant progenitor cells; moreover, c-kitdull progenitor cells, unlike c-kitbright progenitor cells, require multiple cytokines to be recruited to proliferate and develop in culture into c-kitbright progenitor cells. This suggests that the most primitive murine progenitors might be c-kitdull.281

The different conclusions reached in these studies might simply reflect that LTRC are heterogeneous with regard to c-kit expression and that differences in purification strategies and reconstitution assays might result in enrichment and detection of different subpopulations of stem cells. For instance, it is possible that the in vitro (cytokine stimulation) and in vivo (5-FU treatment) manipulation of these cells might modulate (up or down) the expression of c-kit. Thus, although a certain level of c-kit expression might prove useful for purification and characterization of LTRC by one specific procedure, it is not necessarily transferable to other methods.