Abstract

We previously showed that a peptide (PR1) derived from the primary granule enzyme proteinase 3 induced peptide specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in a normal HLA-A2.1+ individual. These CTL showed HLA-restricted cytotoxicity to myeloid leukemias (which overexpress proteinase 3). To further investigate their antileukemic potential, we studied the ability of PR1-specific CTL, derived from two HLA-A2.1+ normal individuals, to inhibit colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) from normal and leukemic individuals. CTL from 20 day PR1 peptide-pulsed lymphocyte cultures showed 89% to 98% HLA-A2.1–restricted colony inhibition of chronic myeloid leukemia targets. Colony formation in normal HLA-A2.1+ bone marrow or HLA-A2.1− CML cells was not inhibited. Sequencing of the exon encoding PR1 showed that colony inhibition was not caused by polymorphic differences in proteinase 3 between effectors and targets. Analysis by flow cytometry showed that proteinase 3 was overexpressed in the leukemia targets compared with normal marrow targets (median channel fluorescence 1,399 v 298, P = .009). These results show that PR1-specific allogeneic T cells preferentially inhibit leukemic CFU-GM based on overexpression of proteinase 3, and that proteinase 3-specific CTL could be used for leukemia-specific adoptive immunotherapy.

EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES and clinical results indicate that donor lymphocytes have a powerful antileukemic effect which makes a major contribution to the cure of myelogenous leukemias after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT).1-3 Although it is clear that chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and some acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) are susceptible to this graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect, the antigens that drive the donor's lymphocyte response are not known.

To search for candidate proteins that might generate peptide antigens initiating leukemia-restricted T-cell responses, we studied primary granule proteins as examples of well-expressed myeloid-restricted proteins. From a number of candidates, a peptide PR1 (amino acids [aa] 169-177) derived from proteinase 3 was selected because of its ability to bind to HLA-A2.1, an allele expressed in 49% of the population. PR1-specific CTL lines were found to be cytotoxic to myeloid leukemia cells overexpressing proteinase 3 but not normal marrow cells or other proteinse 3-negative HLA-A2.1+ targets.4

To determine the potential of PR1-reactive CTL for adoptive immunotherapy of leukemia, we investigated their interaction with leukemic and normal marrow colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) and the relationship between the effects on colony growth and proteinase 3 expression in the target. In addition, we sequenced the exon 4 from proteinase 3 in effectors and targets to determine whether the T-cell response toward the targets was based on polymorphic differences in the segment encoding PR1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptide synthesis.PR1 (aa 169-177) peptide (VLQELNVTV), derived from the azurophilic granule protein proteinase 3, was synthesized by Biosynthesis (Lewisville, TX) to a minimum of 95% purity as measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. The peptide sequence of PR1 was previously chosen according to its predicted binding to the HLA A2.1 motif based on the known binding affinities of other previously published peptide sequences.5 Confirmation of binding of PR1 to HLA-A2.1 has been previously demonstrated.4

Patients and donors.After informed consent, cells from patients with CML (P1-P5), as well as the paired HLA identical healthy BM donors for those patients (D1-D5), were obtained from BM or peripheral blood (PB) before BMT. Cells from two other unrelated HLA-A2.1+ healthy donors were also obtained from PB for generation of the PR1-specific cell lines CTL1 and CTL2. The cells were separated using Ficoll-Hypaque gradient-density (Organon Teknika Co, Durham, NC) and subsequently frozen in RPMI-1640 complete medium (CM: 25 mmol/L HEPES buffer, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin; GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated pooled human AB serum (HS; Pel-Freez, Brown Deer, WI) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) according to standard protocols. Before use, cells were thawed, washed, and suspended in CM + 10% HS.

Cell lines.T2 cells were kindly provided by Dr Licia Rivoltini (NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD). T2 cells are a hybrid human cell line that lack most of the MHC class II region including the known TAP (transporter proteins for antigenic peptide) and proteasome genes.6 They contain the gene HLA-A*0201, but express very low levels of cell surface HLA-A2.1 and are unable to present endogenous antigens.7 These cells were maintained in culture in CM + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; ATLANTA Biologicals, Norcross, GA).

Sequencing of exon 4 of the proteinase 3 gene.Genomic DNA was extract from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of patients and normal donors using a Genomic DNA extraction kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A first amplification of the exon 4 was performed using the following primers: P4-F 5′-TTT GAG GTG GTG GGT GTG GT-3′ (position 5137) and P4-R 5′-AGG CAC AGC ATG AAG CCA CA-3′ (position 5561).8 The reaction mixtures contained 100 ng of genomic DNA, 100 ng of each primer, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2 , 25 mmol/L KCl, and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (PE Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT) in a final volume of 50 μL. Genomic DNA and primers were separated before the first denaturation step using a wax barrier (“Hot Start PCR”). Amplification was performed according to a “Touchdown” protocol (2 minutes at 94°C, then 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 70°C, and 45 seconds at 72°C for 5 cycles with a decrease of 1°C per cycle of the annealing temperature; then 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 65°C, and 45 seconds at 72°C for 25 cycles followed by 8 minutes at 72°C).

A second amplification of 10 or 15 cycles was performed using the same PCR conditions, 1 μL of the first amplification product, and primers with the same sequence and a tail corresponding to the −21 M13 and M13 reverse sequencing primer: MP4-F 5′-TGT AAA ACG ACG GCC AGT TTG AGG TGG TGG GTG TGG T-3′ and MP4-R 5′-CAG GAA ACA GCT ATG ACC AGG CAC AGC ATG AAG CCA CA-3′. The product of the second amplification was purified using the Qiagen PCR kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) and sequenced directly using the ABI Prism Dye Primer Cycle Sequencing kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT). Sequences were then run in the ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems). Several different sequences resulting from independent amplifications were examined for each patient sample tested.

Generation of peptide-specific T cells from healthy human PBMCs.PBMCs from two healthy HLA-A2.1+ donors (CTL1 and CTL2) were stimulated in vitro with PR1 using a protocol adapted from previous studies.4 Briefly, T2 cells were washed three times in serum-free CM and by incubating with peptide at 10 μg/mL for 2 hours in CM. The peptide-loaded T2 cells were then irradiated with 7,500 cGy, washed once, and suspended with freshly isolated PBMCs at a 1:1 ratio in CM supplemented with 10% HS. After 7 days in culture, a second stimulation was performed and the following day, 20 IU/mL of recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) was added. After 14 days in culture a third stimulation was performed, followed on day 15 by addition of rhIL-2. After a total of either 13 or 20 days in culture, the peptide-stimulated T cells were obtained and tested for peptide-specific CFU-GM inhibition of human BM cells derived from patients with leukemia or from normal marrow donors.

Colony inhibition assay.Previously cryopreserved marrow-derived cells were thawed and washed twice with CM + 10% HS and viability, as measured by trypan blue (ABI, Columbia, MD) exclusion, was consistently greater than 90%. These cells were then co-incubated with the CTL line specific for PR1 at an effector:target (E:T) ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours in 0.5 mL of CM + 10% FBS at 37°C after centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 3 minutes to allow for close cell approximation. Control target cells were also centrifuged and incubated for 4 hours in 0.5 mL CM + 10% FBS at 37°C alone.

After a 4-hour incubation, 2.5 mL of methylcellulose containing 50 ng/mL rh stem cell factor (rhSCF), 10 ng/mL rhIL-3, 10 ng/mL rhGM-colony stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF), and 30% FBS, but without erythropoietin (Methocult GF H4534; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), was added to the 0.5 mL of cells bringing the final target cell concentration to 1 × 105 target cells/mL. Cells were then plated in triplicate in 24-mm wells at 1 mL per well and incubated at 37°C before counting CFU-GM on day 13 to 16.

In experiments where supernatant was added to target cells, 0.5 mL of supernatant was collected after the 4 hour co-incubation of effector CTL and target marrow cells at an E:T ratio of 5:1 and added to target cells alone which was then combined with 2.5 mL methylcellulose (final volume, 3.0 mL) and plated in triplicate at 1 × 105 target cells/mL as described above.

CFU-GM were counted on day 13 to 16 and the mean colony counts of three wells was calculated with standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined using the paired two-tailed Student's t-test.

Antibodies and flow cytometry.Cytoplasmic proteinase 3 staining was determined by the following procedure: Cells were permeabilized and fixed with Ortho PermeaFix (Ortho Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ) according to the manufacturer's directions. The cells were stained with 5 μL of proteinase 3 antibody (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp, Westbury, NY) and incubated for 40 minutes at room temperature. The cells were washed once with PBA (PBS with 0.1% NaN3 and 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]). The cells then were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeled goat-antimouse IgG (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature and washed with PBA. Cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Mouse monoclonal anti-HLA-A2.1 antibody BB7.2 was derived from culture supernatant of a hybridoma cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) and was not labeled.

Ten thousand events were acquired with the Becton Dickinson FACScan for proteinase 3 expression, and data was analyzed using CELLQuest (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) software.

RESULTS

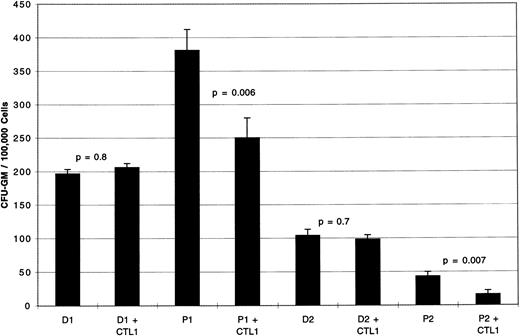

PR1-specific CTL after 13 days in bulk culture inhibit CML CFU-GM.PBMCs from two normal healthy donors heterozygous for HLA-A2.1 (CTL1 and CTL2 cells, Table 1) were stimulated with peptide-pulsed T2 cells using the method described. Figure 1 shows the results of colony inhibition assays using CTL derived from a 13-day PR1 peptide-pulsed culture (CTL1). CFU-GM from patient P1 (CML-CP) and P2 (CML-BC) showed 34% (P = .006) and 63% (P = .007) inhibition, respectively. In contrast there was no inhibition of CFU-GM from normal marrow, D1 and D2, the corresponding HLA identical marrow donors to P1 and P2. Control CTL1 plated alone in methylcellulose under identical experimental conditions at 5 × 105 cells/mL showed no CFU-GM by day 16 (data not shown).

Patient and Donor HLA Types

| Patient/Donor . | Cell Description . | HLA-A . | HLA-B . | HLA-DR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL1 | CTL line 1 | 1,2 | 8,27 | 3,16 |

| CTL2 | CTL line 2 | 2,29 | 44,60 | 4,7 |

| D1 | Normal marrow | 1,2 | 35,58 | 4,16 |

| D2 | Normal marrow | 2,28 | 35,41 | 9,14 |

| D3 | Normal marrow | 2,26 | 13,58 | 7,7 |

| D4 | Normal marrow | 1,2 | 63,63 | 13,8 |

| D5 | Normal marrow | 1,28 | 14,38 | 7,14 |

| P1 | CML-CP | 1,2 | 35,58 | 4,16 |

| P2 | CML-BC | 2,28 | 35,41 | 9,14 |

| P3 | CML-BC | 2,26 | 13,58 | 7,7 |

| P4 | CML-AP | 1,2 | 63,63 | 13,8 |

| P5 | CML-CP | 1,28 | 14,38 | 7,14 |

| Patient/Donor . | Cell Description . | HLA-A . | HLA-B . | HLA-DR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL1 | CTL line 1 | 1,2 | 8,27 | 3,16 |

| CTL2 | CTL line 2 | 2,29 | 44,60 | 4,7 |

| D1 | Normal marrow | 1,2 | 35,58 | 4,16 |

| D2 | Normal marrow | 2,28 | 35,41 | 9,14 |

| D3 | Normal marrow | 2,26 | 13,58 | 7,7 |

| D4 | Normal marrow | 1,2 | 63,63 | 13,8 |

| D5 | Normal marrow | 1,28 | 14,38 | 7,14 |

| P1 | CML-CP | 1,2 | 35,58 | 4,16 |

| P2 | CML-BC | 2,28 | 35,41 | 9,14 |

| P3 | CML-BC | 2,26 | 13,58 | 7,7 |

| P4 | CML-AP | 1,2 | 63,63 | 13,8 |

| P5 | CML-CP | 1,28 | 14,38 | 7,14 |

Abbreviations: CTL1, cytotoxic T lymphocytes derived from a normal donor; CTL2, cytotoxic T lymphocytes derived from a second normal donor; CML-CP, chronic myelogenous leukemia, chronic phase; CML-AP, chronic myelogenous leukemia, accelerated phase; CML-BC, chronic myelogenous leukemia, blast crisis.

CFU-GM inhibition by PR1-specific CTL1 against marrow from patients with CML or their HLA identical normal donors. Day 13 PR1-pulsed CTL1 inhibit CFU-GM from P1 (CML-CP) by 34% compared to P1 cultured without CTL1 (P = .006). Similarly, day 13 PR1-pulsed CTL1 inhibit CFU-GM from P2 (CML-BC) by 63% compared with P2 cells cultured in the absence of CTL1 (P = .007). CTL1 did not inhibit CFU-GM from the HLA-identical normal marrow donors, D1 and D2, to patients P1 and P2, respectively. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

CFU-GM inhibition by PR1-specific CTL1 against marrow from patients with CML or their HLA identical normal donors. Day 13 PR1-pulsed CTL1 inhibit CFU-GM from P1 (CML-CP) by 34% compared to P1 cultured without CTL1 (P = .006). Similarly, day 13 PR1-pulsed CTL1 inhibit CFU-GM from P2 (CML-BC) by 63% compared with P2 cells cultured in the absence of CTL1 (P = .007). CTL1 did not inhibit CFU-GM from the HLA-identical normal marrow donors, D1 and D2, to patients P1 and P2, respectively. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

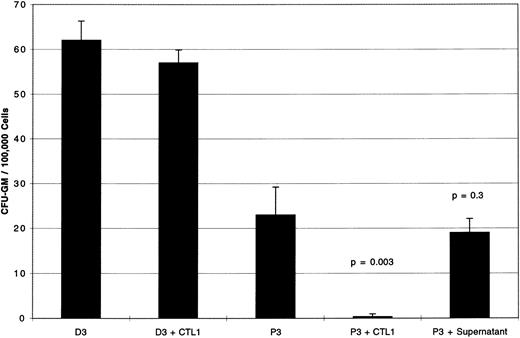

Cell contact is required for inhibition of CML CFU-GM by PR1-specific CTL.After 20 days of bulk culture and 3 rounds of stimulation with PR1, colony inhibition tests were performed with cells from P3 (CML-BC) or the HLA identical normal donor D3 at E:T ratio of 5:1.

Figure 2 shows a 98% inhibition of P3 CFU-GM by CTL1 (P = .003). There was no effect of CTL1 on CFU-GM from normal donor marrow D3. When supernatant, derived from a 4-hour co-incubation of CTL1 with P3 BM cells, was combined with a further sample of P3 BM cells, incubated for 4 hours at 37°C and then plated in methylcellulose, no CFU-GM inhibition was seen. This suggested that cell contact was required for inhibition of CFU-GM, and that inhibitory factors elaborated into the supernatant by CTL1 effector cells were not responsible for colony inhibition.

Supernatant derived from PR1-pulsed CTL1 has no effect on CFU-GM. Day 20 PR1-pulsed CTL1 inhibit CFU-GM from P3 (CML-BC) by 98% compared to P3 cultured without CTL1 (P = .003). CTL1 did not inhibit CFU-GM from D3, the HLA identical normal marrow donor to patient P3. Supernatant taken after a 4-hour incubation of CTL1 with P3 and added back to fresh P3 did not inhibit CFU-GM, indicating that cell contact between CTL1 and targets is required for colony inhibition. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

Supernatant derived from PR1-pulsed CTL1 has no effect on CFU-GM. Day 20 PR1-pulsed CTL1 inhibit CFU-GM from P3 (CML-BC) by 98% compared to P3 cultured without CTL1 (P = .003). CTL1 did not inhibit CFU-GM from D3, the HLA identical normal marrow donor to patient P3. Supernatant taken after a 4-hour incubation of CTL1 with P3 and added back to fresh P3 did not inhibit CFU-GM, indicating that cell contact between CTL1 and targets is required for colony inhibition. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

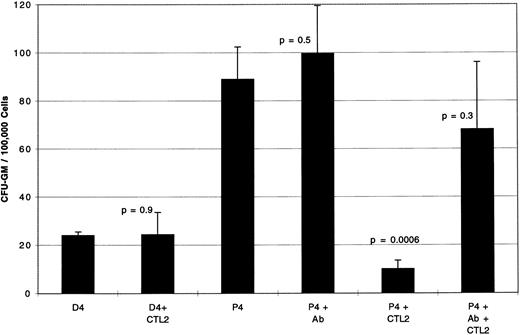

Inhibition of CML CFU-GM by PR1-specific CTL is HLA-A2.1 restricted.To demonstrate that colony inhibition was HLA-A2.1-restricted, blocking experiments were performed with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for HLA-A2.1 as shown in Fig 3. Using a 20-day-old CTL line, CTL2, derived from another healthy allogeneic donor, and BM cells from P4 (CML-AP), CTL induced an 89% CFU-GM inhibition (P = .0006), which was partially blocked by addition of antibody to HLA-A2.1 during the 4-hour co-incubation. There was no inhibition of CFU-GM from D4, the HLA-identical normal marrow donor of P4, after a 4-hour co-incubation with CTL2. Control CTL2 plated alone in methylcellulose under identical experimental conditions at 5 × 105 cells/mL showed no CFU-GM by day 16 (data not shown).

CFU-GM inhibition is abrogated by blocking antibody to HLA-A2.1, indicating MHC-I–restricted inhibition of targets. Day 20 PR1-pulsed CTL2 inhibit CFU-GM from P4 (CML-AP) by 89% compared to P4 cultured without CTL2 (P + .0006). CTL2 did not inhibit CFU-GM from the D4, the HLA-identical normal marrow donor to patient P4. There was no effect on CFU-GM when anti-HLA-A2.1 antibody is added to P4 alone; however, when antibody was added during the 4-hour incubation of CTL2 with P4 colony growth is restored by 66%. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

CFU-GM inhibition is abrogated by blocking antibody to HLA-A2.1, indicating MHC-I–restricted inhibition of targets. Day 20 PR1-pulsed CTL2 inhibit CFU-GM from P4 (CML-AP) by 89% compared to P4 cultured without CTL2 (P + .0006). CTL2 did not inhibit CFU-GM from the D4, the HLA-identical normal marrow donor to patient P4. There was no effect on CFU-GM when anti-HLA-A2.1 antibody is added to P4 alone; however, when antibody was added during the 4-hour incubation of CTL2 with P4 colony growth is restored by 66%. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

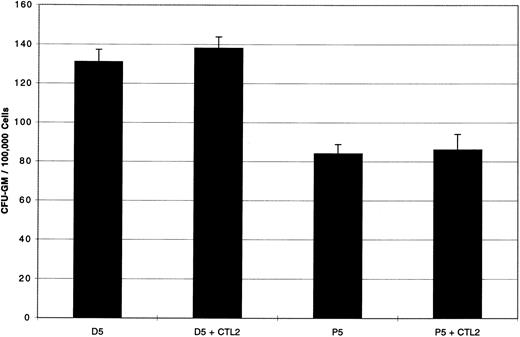

Further evidence that the effect of colony inhibition is HLA-A2.1 restricted is shown in Fig 4. Here, CFU-GM both from the HLA-A2.1 negative patient P5 (CML-CP) and from the HLA identical normal marrow donor, D5, showed no inhibition, affirming that the effect of colony inhibition is HLA-A2.1 restricted.

CFU-GM from HLA-A2.1 negative targets are not inhibited by PR1-pulsed CTL2. Day 20 PR1-pulsed CTL2 did not inhibit CFU-GM from the HLA-A2.1 negative patient P5 (CML-CP), nor D5, the HLA identical normal marrow donor to patient P5. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

CFU-GM from HLA-A2.1 negative targets are not inhibited by PR1-pulsed CTL2. Day 20 PR1-pulsed CTL2 did not inhibit CFU-GM from the HLA-A2.1 negative patient P5 (CML-CP), nor D5, the HLA identical normal marrow donor to patient P5. Effectors were incubated with target cells at E:T ratio of 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C before plating in methylcellulose, and colonies were counted on day 14 of culture. Three replicate wells were used to determine CFU-GM and data are displayed as mean colony counts ± standard deviation.

No polymorphic differences found in PR1-encoding region in PR1-specific CTL1 effector cells or marrow target cells.We considered the possibility that the inhibition of target cells by PR1-specific CTL was caused by polymorphisms in the gene encoding the peptide between the effector cells and the targets. Therefore, we sequenced the exon encoding the PR1 peptide in the CTL1 effector cells and in two donor-patient target pairs. The gene for proteinase 3, found on chromosome 19, contains 5 exons and PR1 is encoded within the fourth exon. Exon 4 was amplified by PCR from both effector and target cells using primers located in the two introns upstream and downstream of this exon. A second round of amplification allowed the addition of tails corresponding to the M13 sequencing primers (−21 and reverse) for direct sequencing of the PCR product. The differences found between the original sequence8 and all of the sequences in the subjects tested were located outside the coding region. The exon 4 sequence was found to be identical in effectors and targets. Therefore, the inhibition of CFU-GM could not be explained by effector cell recognition of a polymorphic difference in PR1 in the targets.

CFU-GM inhibition is related to proteinase 3 overexpression in target cells.Target cells were examined for cytoplasmic proteinase 3 expression by flow cytometry. After permeabilizing the cell membrane, indirect staining was performed using an antibody to proteinase 3 and a second FITC-labeled antibody, followed by flow cytometry. Table 2 lists the percentage of cells in the sample population that stain positive for proteinase 3 and the median fluorescence intensity of intracellular proteinase 3 staining. Median fluorescence intensity of leukemia samples was nearly five times the median fluorescence intensity of normal samples (1,399 v 298, P = .009).

Proteinase 3 Expression

| Patient/Donor . | % Positive Cells . | Median Channel Fluorescence . |

|---|---|---|

| CTL1 | 0 | 0 |

| CTL2 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | 73.4 | 288 |

| D2 | 80.8 | 267 |

| D3 | 77.6 | 337 |

| D4 | 84.5 | 301 |

| D5 | 64.6 | 247 |

| P1 | 89 | 1,011 |

| P2 | 98.6 | 1,866 |

| P3 | 66.2 | 1,437 |

| P4 | 94.7 | 1,281 |

| P5 | 87.6 | 1,641 |

| Patient/Donor . | % Positive Cells . | Median Channel Fluorescence . |

|---|---|---|

| CTL1 | 0 | 0 |

| CTL2 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | 73.4 | 288 |

| D2 | 80.8 | 267 |

| D3 | 77.6 | 337 |

| D4 | 84.5 | 301 |

| D5 | 64.6 | 247 |

| P1 | 89 | 1,011 |

| P2 | 98.6 | 1,866 |

| P3 | 66.2 | 1,437 |

| P4 | 94.7 | 1,281 |

| P5 | 87.6 | 1,641 |

DISCUSSION

In a previous study we showed that a CTL line specific for PR1, a 9-mer peptide derived from proteinase 3 that bound with high affinity to HLA-A2.1, was capable of preferentially lysing HLA-A2.1 positive myeloid leukemia targets.4 We further showed that the degree of cell lysis correlated with the degree of cytoplasmic over-expression of proteinase 3.4 We chose to examine proteinase 3 as a potential T-cell target because of its overexpression in leukemia cells9 and because T cells from patients with the autoimmune disease Wegener's granulomatosis proliferated in response to purified proteinase 3,10 which suggested that it might be easier to elicit T-cell responses to peptides derived from the protein.

To better define whether PR1-specific CTL might have antileukemic clinical potential, we studied the effect of those CTL on clonogenic leukemic precursors. Using a CFU-GM inhibition assay, we examined the effect of PR1-specific CTL against BM cells from five healthy donors and their corresponding HLA identical BMT recipients with CML. After only 13 days of in vitro stimulation, PR1-specific CTL showed 34% to 63% inhibition of CML progenitors. Inhibition increased after 20 days of PR1 stimulation to 89% to 98%. Comparable leukemic CFU-GM inhibition was observed in all stages of CML evolution, from chronic phase to blast crisis. Importantly, there was no colony inhibition of any of the HLA identical normal donor marrows.

Because the effectors and the targets were derived from unrelated individuals, we considered the possibility that a polymorphic difference that changed the amino acid sequence in the region encoding the PR1 peptide in the CTL effectors and the different target cells (normal donor cells and patient cells) could account for the T-cell response. For instance, if the peptide sequences of the PR1 peptide were identical in both the effector CTL and in the leukemia cells, but different in the normal donor cells (resulting in the coding of a peptide different from PR1), then the observed effect of leukemia-specific CFU-GM inhibition could be explained by the shared polymorphism between the leukemia patients and the unrelated CTL donor. However, sequence analysis of the proteinase 3 exon 4 (which encodes PR1) in one of the effector lines and all of the target cell populations showed no differences in the coding regions. Examination by flow cytometry of cytoplasmic proteinase 3 showed nearly a fivefold increased expression of the protein in the the majority of marrow cells in all of the CML patients compared with their HLA identical donors. We have previously shown that specific cell lysis of leukemic targets by PR1-specific CTL was proportional to the amount of cytoplasmic proteinase 3 expression in the targets. Although one patient with chronic phase CML in our previous study showed as much as a 25-fold increase in proteinase 3 expression over normal marrow cells, all other chronic-phase patients we have investigated have shown an increased level of proteinase 3 that is similar to the fivefold increased level reported in this study. This level of proteinase 3 overexpression correlated with high specific cell lysis of leukemia targets of 55% to 75%,4 and this study shows that leukemia-specific CFU-GM inhibition of 89% to 98% by PR1-specific CTL is related to that same level of proteinase 3 overexpression. Future studies will investigate whether the PR1 peptide itself is also overexpressed in the MHC I groove on the target cell surface.

It remains unclear why PR1 is retained in the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire of normal healthy adults with no clinical evidence of an autoimmune disorder, such as Wegener's granulomatosis. It may be that this peptide is not the specific T-cell target of that disease, or it may relate to differences in peptide processing and presentation in Wegener's granulomatosis patients. There is, however, precedence for peptides derived from normal proteins that can be recognized by T cells in normal adults that do not appear to be associated with disease.11-14 This may occur by a mechanism whereby the TCR has intermediate avidity for the antigen allowing for adequate positive thymic selection, but inadequate negative selection and thus these potentially auto-reactive T cells escape to the periphery and are subject to peripheral tolerance mechanisms.15 If such T cells capable of recognizing PR1 exist in leukemia patients, they may be ineffective at eliminating the leukemia because of an acquired state of anergy whereby the T cells recognize their proteinase 3 target peptide but do not lyse the target cell because of an absence of the proper costimulatory signals.16

In total, these results suggest that PR1 may be a useful therapeutic target for adoptive allogeneic cellular strategies to treat CML or other myeloid leukemias, because PR1-specific CTL spare normal marrow progenitors and preferentially target leukemia progenitors. PR1 appears to be highly immunogenic because only three rounds of in vitro stimulation results in PR1-specific CTL that inhibit leukemic colony formation by as much as 98%, which may be sufficient to induce remissions in patients. It is unlikely that large numbers of such leukemia-selective effector CTL would be required because as few as 1 × 107 T cells/kg of unselected allogeneic peripheral blood T cells are sufficient to induce remissions in patients with CML (with estimated leukemic burdens of 1010 to 1012 cells).17 Because CD34+ cells have been found to express mRNA for proteinase 3 (data not shown), it is probable that progenitors expressing low levels of proteinase 3 could escape attack by PR1-specific CTL, whereas leukemia progenitors that overexpress the protein would remain susceptible to attack. Therefore, any PR1-specific CTL adoptively transferred to treat patients would be expected to attack early leukemia progenitors and allow normal hematopoietic progenitors to expand, thus contributing to remission.

Address reprint requests to Jeffrey J. Molldrem, MD, Department of Hematology, Section of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030-4095.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal