Abstract

Despite increasing reports of life-threatening Fusarium infections, little is known about its pathogenesis and management. To evaluate the epidemiology, clinicopathologic features, and outcome of invasive fusariosis in patients with hematologic cancer, we conducted a retrospective study of invasive fusarial infections in patients with hematologic malignancy treated at a referral cancer center over a 10-year period (1986 to 1995), as well as a literature review. Forty patients with disseminated and three patients with invasive lung infection were included in the analysis. All patients were immunocompromised. The infection occurred in three patients postengraftment following bone marrow transplantation. All patients were diagnosed antemortem. Thirteen patients responded to therapy, but the infection relapsed in two of them. Response was associated with granulocyte transfusions, amphotericin B lipid formulations (four patients each), and an investigational triazole (two patients). Resolution of infection was only seen in patients who ultimately recovered from myelosuppression. Portal of entry was the skin (33%), the sinopulmonary tree (30%), and unknown (37%). Fusarium causes serious morbidity and mortality, and may mimic aspergillosis. The infection seems to respond to newer therapeutic approaches, but only in patients with ultimate recovery from myelosuppression, and it may relapse if neutropenia recurs.

DISSEMINATED FUNGAL infections constitute one of the most difficult challenges for clinicians caring for patients with hematologic cancer.1-8 Although the incidence of hematogenous candidiasis has been significantly reduced with the introduction of fluconazole prophylaxis, the opportunistic molds have become the leading cause of infectious mortality in this patient population.9-15 Aspergillosis remains clearly the most common mold infection in patients with hematologic cancer.16-18 However, new opportunistic pathogens have now emerged as a cause of life-threatening infection worldwide. The most frequent of these pathogens is Fusarium, which has been reported to cause disseminated infections in 42 reports from different institutions treating patients with hematologic malignancies worldwide.19-60 Infection with Fusarium is associated with a high mortality and may respond to novel therapies.55-62 Since infection with this organism may mimic aspergillosis, patients are usually treated with amphotericin B, an agent with poor activity against fusariosis.20,27 63-65 Hence, early diagnosis of fusariosis is of paramount importance. Yet despite increasing reports of fatal infections with this organism, little is known about the pathogenesis, clinical characteristics, and management of these infections. In this report, we describe 43 patients with hematologic cancer who developed invasive Fusarium infection during the course of the disease. We also review the worldwide literature (54 patients) and present novel concepts regarding the pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of Fusarium infection.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The medical records of patients with positive cultures for Fusarium species treated at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center between January 1986 and December 1995 were reviewed to determine the pathogenesis, clinical characteristics, and management of patients with invasive Fusarium infection.

Invasive organ infection was documented by both culture and histopathologic examination of the involved organ. Disseminated infection was defined as involvement of at least two noncontiguous organs by Fusarium species in association with more than one positive culture. Patients with fungemia alone or infection at a single extrapulmonary site and patients with an underlying disease other than hematologic cancer were excluded even if they had evidence of multiorgan involvement. Laboratory identification of Fusarium species was conducted as previously reported.20 A literature search based on MEDLINE and CANCERLIT was conducted for the period 1976 to 1995, and only patients with hematologic cancer and invasive infections were analyzed. Findings from the literature search were then compared with those obtained from our series.

RESULTS

Thirty-eight patients with invasive or disseminated Fusarium infection were identified during the study period. Four cases of disseminated and one case of invasive Fusarium infection previously reported from our institution were also added.19 20 The baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Thirty patients had acute leukemia, mostly acute nonlymphocytic, and only five patients were in remission from the underlying disease at the time of infection diagnosis. Twelve patients had undergone bone marrow transplantation (allogeneic in nine), and the remaining patients had received cytotoxic chemotherapy alone. Two of nine patients who underwent allogeneic transplantation developed the infection before engraftment (days 13 and 30), and the remaining seven had postengraftment fusariosis (days 43, 44, 48, 59, 73, 82, and 151). Except for seven patients who had an adequate neutrophil count, all patients were neutropenic at presentation. Of nine allogeneic transplant recipients, four had grade 2 or higher graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Fourteen patients were receiving adrenal corticosteroids. Most patients had concomitant bacterial or fungal infections; seven patients had a history of invasive fungal infection (disseminated candidiasis in four and aspergillosis in three).

Characteristics of Patients With Hematologic Cancer and Invasive or Disseminated Fusarial Infection: Comparison Between the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience and the Published Literature

| Characteristic . | M.D. Anderson . | Literature . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . |

| Patients | 43 | 54 | ||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| Median | 43 | |||

| 31 | ||||

| Range | 14-78 | |||

| 2-71 | ||||

| Sex (male/female) | 24/19 | |||

| 35/19 | ||||

| Underlying disease | ||||

| Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | 23 | 53 | 26 | 48 |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 7 | 16 | 20 | 37 |

| Lymphoproliferative disorders | 13 | 31 | 8 | 15 |

| Neutropenia at diagnosis | ||||

| ANC < 1,000/μL | 36 | 84 | 54 | 100 |

| ANC < 100/μL | 28 | 65 | 22 | 41* |

| BMT | 12 | 28 | 16 | 30 |

| Autologous | 3 | 25 | 6 | 33 |

| Allogeneic | 9 | 75 | 12 | 67 |

| Culture-documented sites of involvement | ||||

| Skin | 39 | 91ρ | 39 | 72 |

| Bloodstream | 18 | 42 | 30 | 56 |

| Eye | 3 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| Bone | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Radiologic evidence in lung† | 36 | 84 | 16 | 70 |

| Nonspecific infiltrates | 29 | 81 | 12 | 52 |

| Nodular lesions | 5 | 14 | 3 | 13 |

| Cavitary lesions | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Radiologic evidence of sinus involvement‡ | 24 | 71 | 11 | 79 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Resolution of infection1-155 | 13 | 30 | 26 | 48 |

| Death with disseminated infection1-154 | 30 | 70 | 28 | 52 |

| Characteristic . | M.D. Anderson . | Literature . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . |

| Patients | 43 | 54 | ||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| Median | 43 | |||

| 31 | ||||

| Range | 14-78 | |||

| 2-71 | ||||

| Sex (male/female) | 24/19 | |||

| 35/19 | ||||

| Underlying disease | ||||

| Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | 23 | 53 | 26 | 48 |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 7 | 16 | 20 | 37 |

| Lymphoproliferative disorders | 13 | 31 | 8 | 15 |

| Neutropenia at diagnosis | ||||

| ANC < 1,000/μL | 36 | 84 | 54 | 100 |

| ANC < 100/μL | 28 | 65 | 22 | 41* |

| BMT | 12 | 28 | 16 | 30 |

| Autologous | 3 | 25 | 6 | 33 |

| Allogeneic | 9 | 75 | 12 | 67 |

| Culture-documented sites of involvement | ||||

| Skin | 39 | 91ρ | 39 | 72 |

| Bloodstream | 18 | 42 | 30 | 56 |

| Eye | 3 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| Bone | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Radiologic evidence in lung† | 36 | 84 | 16 | 70 |

| Nonspecific infiltrates | 29 | 81 | 12 | 52 |

| Nodular lesions | 5 | 14 | 3 | 13 |

| Cavitary lesions | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Radiologic evidence of sinus involvement‡ | 24 | 71 | 11 | 79 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Resolution of infection1-155 | 13 | 30 | 26 | 48 |

| Death with disseminated infection1-154 | 30 | 70 | 28 | 52 |

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; BMT, bone marrow transplantation.

The exact ANC was not mentioned in 31 patients reported in the literature.

Chest x-ray findings were not discussed in 31 cases reported in the literature; in 7 cases (30%), they were normal. Radiologic evaluation was available for all of our patients: in 7 patients (16%), radiologic evaluation of the lungs was normal.

Thirty-four and 14 patients, respectively, had radiologic examination of the sinuses.

ρ Skin not involved in 4 of 43 patients; in 4 patients, description of skin lesions was not available.

Resolution of infection occurred only in patients who recovered from myelosuppression.

Autopsy documentation was obtained in 41% of our patients who died with disseminated infection and 17% of cases, respectively. Two of our patients died with disseminated infection at a subsequent recurrent episode of Fusarium infection after having cleared a first episode of disseminated fusariosis.

Thirty patients were receiving antifungal prophylaxis for a median of 13 days (range, 2 to 100). Prophylaxis consisted of fluconazole (22 patients), intravenous amphotericin B (five patients), itraconazole (two patients), or ketoconazole (one patient).

The most common presentation of the infection was persistent fever refractory to antibacterial and antifungal therapy (35 patients). Other findings at presentation included sinusitis (11 patients), painful skin lesions (six patients), and pneumonia (six patients). Myalgias were part of the clinical presentation in three patients, and one patient each presented with hemoptysis and altered mental status.

Infection documentation was obtained from the bloodstream of 18 patients and from the nails of five patients with onychomycoses and concomitant toe or finger cellulitis. The infection was documented from a bone and a deep-tissue ocular specimen in three patients each. Brain involvement was presumed in four patients. Pulmonary involvement was presumed in 36 patients (84%), either as nonspecific infiltrates in 29 (bilateral in 18) or as nodular lesions in five (bilateral in all five); two patients had a cavitary lung lesion. Twenty-four of 34 patients (71%) in whom radiologic evaluation of the sinuses was obtained had positive findings. These findings were limited to the maxillary or ethmoid sinuses in 19 and four patients, respectively. Abnormal findings in at least two sinuses were noted in the remaining patients. Radiologic findings consisted mainly of mucosal thickening or opacification of the sinuses.

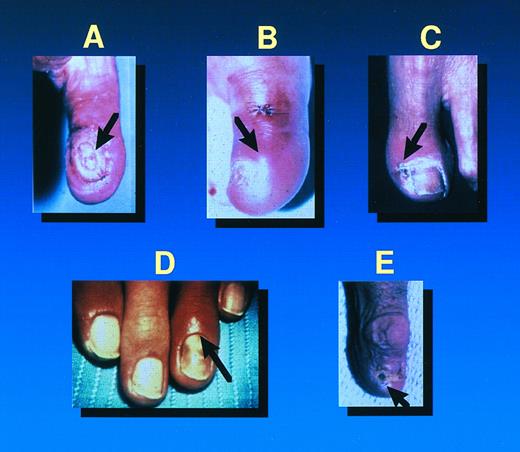

Primary fusarial skin lesions: Cellulitis at the site of a wound (A) or at the site of a pre-existing onychomycosis (B-E) with surrounding cellulitis.

Primary fusarial skin lesions: Cellulitis at the site of a wound (A) or at the site of a pre-existing onychomycosis (B-E) with surrounding cellulitis.

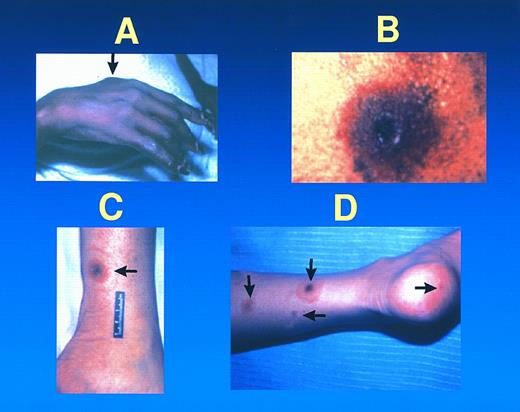

Metastatic fusarial skin lesions tend to evolve from a subcutaneous nodule (A), to a necrotic lesion with a central ulcer and surrounding cellulitis (B), rarely surrounded by a thin rim of erythema (ie, a target lesion) (C). At times, lesions of different ages coexist in the same patient (D).

Metastatic fusarial skin lesions tend to evolve from a subcutaneous nodule (A), to a necrotic lesion with a central ulcer and surrounding cellulitis (B), rarely surrounded by a thin rim of erythema (ie, a target lesion) (C). At times, lesions of different ages coexist in the same patient (D).

Thirty-nine patients (91%) presented with skin lesions, either metastatic (34 patients) or primary (five patients). All 18 patients who had positive blood cultures had metastatic skin lesions. The primary skin lesions consisted of cellulitis at the site of onychomycosis or at a wound site (Fig 1), or facial and periorbital cellulitis in patients with fusarial sinusitis. Metastatic skin lesions included subcutaneous nodular lesions (hemorrhagic in one) and ecthyma gangrenosum–like lesions. Some patients had lesions of different ages that evolved from subcutaneous nodules, usually painful, to erythematous lesions followed by central necrosis (ecthyma gangrenosum–like lesions) (Fig 2). In one of these patients, this latter lesion was surrounded by a thin rim of erythema. Among 12 patients who had undergone bone marrow transplantation, infection occurred before engraftment in three. Of interest, nine bone marrow transplant recipients developed infection after engraftment when they had adequate neutrophil counts. The incidence of fusarial infection was 1.2% among 750 patients who underwent an allogeneic transplant, compared with 0.2% among 1,537 autograft recipients.

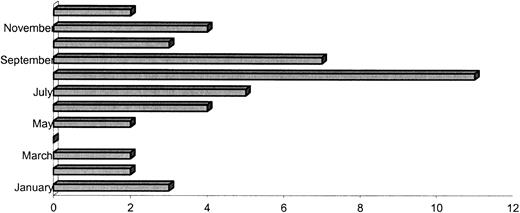

Infections tended to occur predominantly during the rainy season in Houston (May through September), although scattered cases occurred throughout the year (Fig 3). Fusaria were subjected to species analysis in 22 patients: the most common isolated species were solani (12 cases), moniliforme (four cases), and oxysporum (two cases), and proliferatum, dimerum, semitecum, and equiseti were identified in one case each.

Monthly distribution of fusarial infection for the years 1986 to 1995 at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Monthly distribution of fusarial infection for the years 1986 to 1995 at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Diagnosis was made antemortem in all 43 patients. All 43 patients received antifungal therapy consisting of regular or lipid formulations of amphotericin B, or an investigational triazole, SCH 39304 (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ). Granulocyte- (G-CSF) or granulocyte-macrophage (GM-CSF) colony-stimulating factor were part of the therapeutic regimen in 17 patients. Fifteen patients received granulocyte transfusion, seven after donor stimulation with G-CSF. Disseminated or invasive fusarial infection was documented at autopsy in 12 of 14 patients who underwent autopsy examination.

Thirteen patients responded to therapy (30%). Thirty patients died with disseminated infection, including two who initially responded but relapsed after subsequent episodes of neutropenia. Resolution of myelosuppression coincided with a favorable outcome in all 13 responders. Analysis of our cases shows significant differences among the 13 responders and the nonresponders (Table 2). Responders tended to be in remission from the underlying disease (100% v 10%) and to have an adequate number of circulating neutrophils (100% v 0%) and no significant (≥grade II) GVHD (0% v 66%). More responders had infection limited to the skin, sinuses, or lungs (15%) than nonresponders (3%), and had received G-CSF–stimulated white blood cell transfusions (24% v 13%).

Characteristics of Patients With Hematologic Cancer and Fusariosis: Comparison Between Responders and Nonresponders

| Characteristic . | Responders . | Nonresponders . |

|---|---|---|

| . | (n = 13) . | (n = 30) . |

| Age (year) | ||

| Median | 52 | 42 |

| Range | 22-75 | 14-71 |

| Sex (males/females) | 7/6 | 19/11 |

| Underlying disease (n) | ||

| Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | 6 | 17 |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 4 | 3 |

| Other hematologic disorders | 3 | 10 |

| Active underlying disease at start of infection (n) | 10 | 28 |

| Active underlying disease at end of infection (n) | 0 | 27 |

| Patients with neutropenia at start of infection (n) | 9 | 27 |

| Patients with neutropenia at end of infection (n) | 0 | 30 |

| Duration of neutropenia (d) | ||

| Median | 23 | 26 |

| Range | 0-55 | 5-65 |

| Type of transplant (12 patients) (n) | ||

| Autologous | 0 | 3 |

| Allogeneic | 3 | 6 |

| Patients with GVDH at start of infection* (n) | 0 | 4 |

| Prior history of invasive fungal infection (n) | 0 | 7 |

| Cumulative dose of AmB (mg) | ||

| Median | 1,380 | 775 |

| Range | 720-2,740 | 120-4,295 |

| Cumulative dose of liposomal preparations of AmB (mg) | ||

| Median | 7,100 | 5,325 |

| Range | 4,215-31,525 | 1,700-28,995 |

| Patients receiving growth factors (n) | 7 | 10 |

| Start of infection after BMT (d) | ||

| Median | 30 | 46 |

| Range | 13-73 | 7-151 |

| Patients receiving WBC transfusions (G-CSF–elicited) (n) | 3 | 4 |

| Extent of infection (n) | ||

| Disseminated | 11 | 29 |

| Limited† | 2 | 1 |

| Characteristic . | Responders . | Nonresponders . |

|---|---|---|

| . | (n = 13) . | (n = 30) . |

| Age (year) | ||

| Median | 52 | 42 |

| Range | 22-75 | 14-71 |

| Sex (males/females) | 7/6 | 19/11 |

| Underlying disease (n) | ||

| Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | 6 | 17 |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 4 | 3 |

| Other hematologic disorders | 3 | 10 |

| Active underlying disease at start of infection (n) | 10 | 28 |

| Active underlying disease at end of infection (n) | 0 | 27 |

| Patients with neutropenia at start of infection (n) | 9 | 27 |

| Patients with neutropenia at end of infection (n) | 0 | 30 |

| Duration of neutropenia (d) | ||

| Median | 23 | 26 |

| Range | 0-55 | 5-65 |

| Type of transplant (12 patients) (n) | ||

| Autologous | 0 | 3 |

| Allogeneic | 3 | 6 |

| Patients with GVDH at start of infection* (n) | 0 | 4 |

| Prior history of invasive fungal infection (n) | 0 | 7 |

| Cumulative dose of AmB (mg) | ||

| Median | 1,380 | 775 |

| Range | 720-2,740 | 120-4,295 |

| Cumulative dose of liposomal preparations of AmB (mg) | ||

| Median | 7,100 | 5,325 |

| Range | 4,215-31,525 | 1,700-28,995 |

| Patients receiving growth factors (n) | 7 | 10 |

| Start of infection after BMT (d) | ||

| Median | 30 | 46 |

| Range | 13-73 | 7-151 |

| Patients receiving WBC transfusions (G-CSF–elicited) (n) | 3 | 4 |

| Extent of infection (n) | ||

| Disseminated | 11 | 29 |

| Limited† | 2 | 1 |

Grade II or greater acute GVHD of extensive chronic GVHD.

Primary skin, sinus, lung.

We attempted to define the primary source of infection based on clinical and laboratory findings. The two most common sites of infection were the skin (14 patients) or the sinopulmonary tree (13 patients). Skin breakdown was secondary to trauma (eight patients), onychomycosis with associated cellulitis (four patients), and a spider bite (two patients). In 16 patients, the primary source of infection could not be determined, although the sinopulmonary tree was possibly the primary source of infection in four patients.

The literature search yielded 42 reports with a total of 54 cases of invasive or disseminated fusarial infection in patients with hematologic cancer.19-60 Infections caused by Fusarium have been reported from different institutions treating patients with cancer from four continents, America (40 reports), Europe (30 reports), Asia (seven reports), and Australia (one report).19-99 Not all of these reports were included in our comparison, because they did not fulfill the criteria for disseminated or invasive fusariosis and some of them occurred in patients without hematologic malignancy. Clinicopathologic features were compared in 54 reported patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy and invasive or disseminated fusarial infection versus patients treated at our Center (Table 1).

Fusarium solani was the predominantly isolated species both in the literature and in our series, followed by F moniliforme, F oxysporum, and F proliferatum. There was only one report of infection caused by F napiforme,49 whereas we isolated F semitecum, F dimerum, and F equiseti in one case each of our current series.

Patient characteristics were comparable in both series regarding sex, underlying disease (mostly acute nonlymphocytic leukemia with active disease), therapy (cytotoxic chemotherapy with or without bone marrow transplantation), and neutropenia, although patients from our center were older.

A specific portal of entry of Fusarium infection was discussed in only a few reports, and was presumed to be the respiratory tract in five reports.28,35,44,54,73 Onychomycosis was reported as the potential primary source of the infection in only three reports,28,77,81 whereas the infection was considered secondary to wound contamination in four case reports.25,28,39,73 In two reports, the infection was thought to originate in the gastrointestinal tract.32,67 A catheter was considered the origin of disseminated infection by two studies,24,64 and fungemia by two others.87 88 By contrast, a potential source of entry (skin or respiratory tract) was identified in the majority of our patients.

The clinical presentation of invasive fusarial infection in our patients was similar to that of the reported patients. Fever refractory to antibacterial antibiotics was frequently observed, followed by sinusitis and/or pneumonia. Skin lesions both primary and metastatic were common in both series and consisted mainly of subcutaneous nodules, at times vesicular, and of ecthyma gangrenosum–like lesions with a black necrotic center. Similar to the findings of our series, infection documentation was achieved mainly through cultures of the bloodstream (56%) or the primary or metastatic skin lesions (72%).

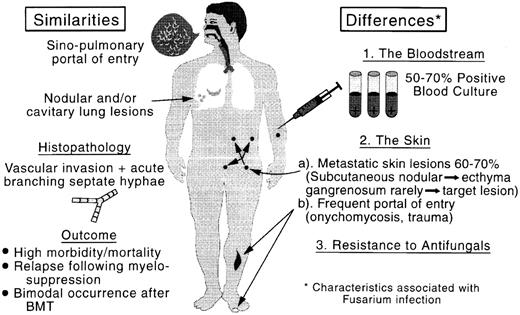

Comparison of the clinicopathologic features of aspergillosis and fusariosis. BMT, bone marrow transplant.

Comparison of the clinicopathologic features of aspergillosis and fusariosis. BMT, bone marrow transplant.

Resolution of infection was reported in a higher proportion of patients (26 of 54, 48%) than in our series (13 of 43, 30%). As expected, recovery from the infection occurred only in patients with resolving myelosuppression, whereas relapse was observed exclusively among patients who received additional myeloablative therapy after an apparent resolution of the initial fusarial infection.

DISCUSSION

This study constitutes the largest series of invasive fusarial infection in a well-defined population of patients with hematologic cancer treated at a single institution. Although our results are in agreement with findings reported by our group and others in smaller series and case reports,19-60 new findings have emerged, possibly due to the larger sample size of our current study and inclusion of consecutive patients: (1) The significant role of the skin as a portal of entry for the infection. Although this has been previously reported by us and others, the importance of this finding had been underestimated, with the majority of the reports focusing on the respiratory route of infection. The incidence observed in our larger series is therefore a better reflection of the role of the skin as a primary source; (2) The response of these infections to novel therapeutic modalities, particularly cytokine-stimulated granulocyte transfusions; (3) The high risk of recurrence following subsequent myelosuppression; (4) The bimodal distribution (before and after engraftment) in bone marrow transplant recipients; (5) The description of the spectrum and evolution of metastatic fusarial skin lesions from subcutaneous lesions, usually painful, to erythematous indurations, followed by ecthyma gangrenosum–like necrotic lesions, which may be surrounded in the occasional patient by a thin rim of erythema. We have coined the term “target lesion” for this finding, which we believe is only seen with fusarial infection; (6) The characterization of the pulmonary radiologic findings, from nonspecific infiltrates to nodular and/or cavitary lesions. However, of note is the fact that not all pulmonary radiologic findings were histopathologically proven to be secondary to fusariosis, and they could have been caused by other pathogens that were not recovered. Confirmation of our radiologic findings by others is needed.

The clinical implications of these new findings are many. Since the skin is frequently the primary source of these life-threatening infections, every attempt to prevent these infections from occurring and/or spreading should be made. Hence, we recommend that patients with hematologic cancer and onychomycosis and/or a significant break in the integrity of skin surfaces who are about to undergo cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or bone marrow transplantation be evaluated by a dermatologist to ascertain the nature of the onychomycosis or skin breakdown and rule out the presence of fusarial infection. These patients are likely to benefit from local therapy including surgical debridement of the infected area and topical application of the antifungal natamycin, known to have adequate antifusarial activity.63 In the presence of cellulitis, a bone scan should be obtained to rule out osteomyelitis, and consideration should be given to resection of all infected tissues. In addition, primary skin lesions following a trauma or a bite, such as a spider bite, should be considered in these high-risk patients as potentially infected by Fusarium species, hence requiring biopsy and culture and surgical debridement if fusarial origin is confirmed. Although amphotericin B and itraconazole have limited activity against fusarial infections, administration of either of these agents (or of the lipid formulations of amphotericin B) in patients with primary fusarial skin lesions who are about to undergo cytotoxic chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation should be seriously considered.

Because of the high rate of relapse and death in patients with a prior history of invasive fusarial infection, clinicians should consider either postponing cytotoxic therapy or using prophylactic G-CSF– or GM-CSF–stimulated granulocyte transfusion if a delay in treating the underlying cancer is not a viable option.100 Since CSF-elicited granulocyte transfusions do not represent the standard of care, this approach should be evaluated in the setting of a research protocol. We believe that this novel therapy modality should also be considered as early as possible in patients with invasive fusarial infection who are likely to have spontaneous recovery from myelosuppression. This recommendation is based on the high mortality rate for disseminated fusariosis in the setting of persistent profound neutropenia101 and the favorable responses seen in patients who received white blood cell transfusions and subsequently had resolution of the myelosuppression.100 The granulocyte transfusions may thus “buy time” until spontaneous recovery occurs. Additional data are needed before granulocyte transfusions can be readily recommended as a standard of care for these patients. The antifungal triazole SCH 39304 is no longer available, but a closely related drug is currently under investigation and may prove useful in this setting.102 Amphotericin B lipid complex is now available in the United States and has been associated with good responses in some patients.103

Our findings with regard to the type of metastatic skin lesions should raise the index of suspicion of fusarial infection and prompt skin biopsy and culture and initiation of appropriate therapy. Since both nodular and cavitary lesions can be observed with fusarial infection, Fusarium should be added to Aspergillus and other pathogens in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary lesions in febrile neutropenic patients with hematologic cancer. Fusarium should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of invasive mold infections following engraftment in bone marrow transplant recipients, since fusarial infections may mimic aspergillosis, which is known to occur postengraftment in bone marrow transplant recipients (Fig 4).

Our findings also confirm those reported by our group and others including the ability to culture Fusarium from the bloodstream with regularity, the high frequency of metastatic skin lesions, the high mortality rate associated with this infection, the poor antifungal activity of amphotericin B, and the importance of the sinopulmonary tree as a potential portal of entry.101 Appropriate infection-control measures should be taken in cancer wards where fusarial infections have occurred, and an aggressive search for a potential source should be conducted. Our findings also confirm the potential of this infection to cause osteomyelitis,85,104-107 deep infections of the eye with potential of loss of vision,35,108-111 and catheter-related infections,101 hence requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment, including surgical debridement of the infected organ and removal of the venous catheter in patients with catheter-related fungemia.

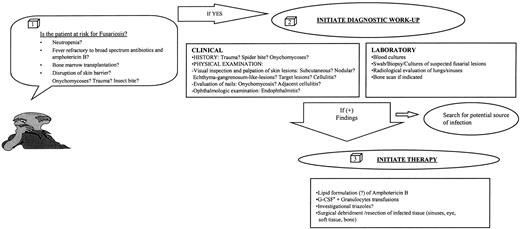

Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of Fusarial infection. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of Fusarial infection. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

The lower response rate observed in our series as compared with the literature could be best explained by the referral pattern at our institution, a tertiary cancer center where heavily pretreated patients with refractory disease are frequently referred, and the higher percentage of patients with disseminated infection in our series. Unfortunately, complete data on most patients reported in the literature were not available, including information such as the status of the underlying disease, the extent of the infection, and the length and duration of neutropenia. In addition, the literature reflects a series of case reports, as opposed to our series of consecutive patients. In general, patients with a successful outcome are more likely to be reported in single case reports than patients who failed to respond to therapy.

Giving the high fatality rate of this infection, every effort at early diagnosis should be made. In Fig 5, we have outlined clues that should raise the index of suspicion for the presence of fusarial infection in this patient population, and practical guidelines for the clinical evaluation and management of this infection are given.

The number of patients included in our study was substantial, but we must point out some of the limitations of our study that stemmed from its retrospective nature. For example, we did not prospectively evaluate the evolution of the skin lesions, the onychomycosis, the radiologic findings, or the rate of bloodstream infection, nor did we conduct a therapeutic trial focused on this serious infection. In addition, not all of our cases of pulmonary infection were histopathologically documented.

In conclusion, invasive fusarial infections represent an increasing cause of infectious morbidity and mortality in patients with hematologic cancer. These infections are either airborne or inoculated through breakdown of the skin barrier. Once established, these infections are refractory to standard antifungal therapy and appear to respond to novel therapeutic modalities such as investigational or newly released lipid-associated amphotericin B or CSF-stimulated granulocyte transfusions. Every attempt should be made to prevent these infections from occurring.

Address reprint requests to Elias J. Anaissie, MD, Professor of Medicine, The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W Markham, MS 508, Little Rock, AR 72205.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal