Abstract

The tumor suppressor gene wt1 (Wilms' tumor gene) encodes for a zinc finger DNA-binding protein with predominantly transcription repressing properties. Because wt1 has been shown to be expressed in the vast majority of patients with acute myeloid leukemias (AML), we investigated the relevance of wt-1 mRNA expression regarding prognosis and possible prediction of relapse during follow-up. Totally bone marrow-derived blasts of 139 AML patients (129 newly diagnosed AML patients, 22 AML patients again in first relapse, and 10 AML patients analyzed primarily in first relapse) were studied for wt1 mRNA expression. Seventy-seven patients were analyzed for wt1 mRNA expression during follow-up. wt1-specific reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed and the amplification product was visually classified as not, weakly, moderately, or strongly amplified, as described previously. PCR products were quantitated by competitive PCR using a shortened homologous wt1 construct standard in representative cases. The expression of wt1 transcripts was correlated to age, French-American-British (FAB) subtype, phenotype, karyotype, and long-term survival. wt1 mRNA was detectable in 124 of 161 (77%) samples at diagnosis and in first relapse. wt1 expression was independent from age, antecedent myelodysplastic syndrome or FAB subtype, with the exception of a significant difference in M5 leukemias showing wt1 transcripts in only 40% (P = .0025). There was no correlation between the level of wt1 mRNA and response to treatment or the prognostic groups defined by the karyotype. Concerning long-term survival, patients with high levels of wt1 had a significantly worse overall survival (OS) than those with not detectable or low levels. The 3-year OS for all newly diagnosed AMLs was 13% and 38% (P = .038), respectively, and 12% and 43% (P = .014) for de novo AMLs. The difference was more distinct in patients less than 60 years of age. During follow-up, all patients achieving complete remission became wt1 negative. Reoccurrence of wt1 transcripts predicted relapse. The data indicate that high expression of wt1 mRNA is associated with a worse long-term prognosis.

THE TUMOR SUPRESSOR gene wt1 has been identified by cytogenetic deletion analysis of patients with Wilms' tumors.1-3 It is located in the 11p13 region and encodes for a zinc finger DNA-binding protein with four different alternatively spliced transcripts.3-5 The Wt1 protein is a transcription factor with mostly repressing activity on different target genes such as insulin like growth factor-2 (IGF-2),6 platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A),7 macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF ),8 transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF-β1 ),9 and, in addition, its own gene.10 Moreover, in some cases, Wt1 may activate gene expression, as demonstrated for upregulation of PDGF.11,12 wt1 itself has homology to other growth-related genes such as the early growth response-1 (EGR-1) and EGR-2 genes.13

During normal ontogenesis, wt1 is expressed in a time- and tissue-dependent manner mainly in the kidneys and gonads.3,14-16 In Wilms' tumors, its expression persists at a high level. Because different deletions and point mutations in this gene have been described in this tumor as well as in the germline of the same patients, it seems likely that the product of the mutated wt1 gene is involved in carcinogenesis.17,18 Furthermore, wt1 is expressed in syndromes associated with the Wilms' tumor as WAGR syndrome18 and Denys Drash syndrome,19 but also in malignant melanoma20 and ovarian cancer.21

Recently, the expression of wt1 in acute leukemias (AL) and blast crisis of chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML) has been reported by us and others.22-26 In about 75% of all cases analyzed, wt1 transcripts have been demonstrated.26 Mutations of the wt1 gene in AL have been found in about 15% and have been associated with a poor prognosis.27 A possible relevance of wt1 for leukemogenesis or differentiation of immature hematopoietic precursors has been discussed. K562 cells downregulate wt1 mRNA expression during induced erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation.28 The same phenomenon has been observed in differentiation-induced HL60 cells.29 Regarding normal hematopoiesis, we showed transient expression during differentiation of normal CD34+ cells.30

The frequent expression of wt1 in acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs) raises the question of whether it may be used as a marker for minimal residual disease and as a parameter for prognosis. In this study, we evaluated the prognostic value of wt1 gene expression and its relevance as a genetic marker in AML for the detection of minimal residual blast cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.All AML patients entered in this study were classified using the morphologic and cytochemical criteria of the French-American-British (FAB) study group classification.31 Additionally, phenotypical characterization of leukemic blasts was performed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses using a broad panel of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled monoclonal antibodies.

To test wt1 mRNA expression, bone marrow (BM) samples were obtained from 139 consecutive AML patients on particular clinical trials (129 newly diagnosed AMLs, 22 of them again in first relapse, and 10 patients analyzed primarily in first relapse). In 59 patients, the karyotype of blast cells was determined by banding techniques or for major aberrations by fluorescence in situ hybridization. In 77 AML patients, wt1 expression was monitored during follow-up. For this purpose and to ascertain ongoing complete remission (CR), BM was obtained at time of diagnosis, after each chemotherapy cycle, and every 3 months afterwards. Mononuclear cells, including leukemic blasts, were separated by density gradient sedimentation using Ficoll-Hypaque; the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and used for RNA extraction.

The treatment schedule for newly diagnosed AMLs consisted of induction and early consolidation courses with a combination of cytosin-arabinoside (AraC), etoposide, and an anthracyclin (daunorubicin or idarubicin). Patients ≤50 years of age received a late consolidation therapy with a high-dose AraC regimen. Patients more than 50 years of age received an intermediate-dose to high-dose AraC regimen. Informed consent according to the criteria of the local ethical commission was required for participation. Patients in first relapse were treated with intermediate-dose to high-dose AraC and etoposide as described.32

RNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).Total RNA was prepared according to the technique published by Chomczynski and Sacchi33 using the RNAzol B method (Biotex, Houston, TX), redissolved in diethylpyrocarbonat-treated water, and quantitated photometrically and aliquots of 0.5 μg total RNA were reverse transcribed as described.34 Briefly, RNA was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with a mixture of 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (MMLV-RT), 2 μg oligo-dT primer, 0.2 μL 100 mmol/L dNTP, 0.9 μL dithiothreitol, 100 mmol/L, 40 U RNase-inhibitor, and 6 μL 5× MMLV-first strand buffer (250 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 375 mmol/L KCl, 15 mmol/L MgCl2 ) in a total volume of 30 μL. The reaction was stopped by heating to 99°C for 5 minutes and the mixture was diluted to 50 μL with ddH2O. All reagents were purchased from GIBCO/BRL (Berlin, Germany).

PCR was performed as previously described.35,36 The reaction mixture contained 3 μL of the above-mentioned cDNA dilution, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), 20 pmol of each primer, 10 nmol dNTP, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2 , and 10× buffer (500 mmol/L KCl, 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 1% Triton X-100) in a total volume of 50 μL. Oligonucleotides specific for wt1 spanning one intron to exclude DNA contamination were synthesized according to published sequences (5′-primer, 5′-ATGAGGATCCCATGGGCCAGCA; 3′-primer, 5′-CCTGGGACACTGAACGGTCCCCGA).4 Amplifications were performed with 35 cycles under the following conditions. Before amplification, the samples were denatured for 5 minutes at 94°C and the enzyme was subsequently added. The cycles were initiated by denaturing the DNA at 94°C for 30 seconds, followed by an annealing reaction for 30 seconds at 64°C and extending at 72°C for 45 seconds. After the last cycle, a final extension reaction at 72°C for 7 minutes was performed.

The integrity and the amount of RNA for preparation of all cDNAs was analyzed by amplification of the β-actin gene as an internal control (5′-primer, AGCAAGAGAGGCATCCTGACC; 3′-primer, 5′-CTTCATGATGGAGTTGAAGGTAG). Each PCR included a negative control with ddH2O instead of cDNA, a positive control with cDNA derived from the wt1 expressing HEL 92.1.7 cell line (ATCC, Rockville, MD), and a control without RNA for contamination in the reverse transcription reaction.

Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis on an 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The ethidium bromide-stained and photographed amplification product was visually classified as not amplified (−), weakly amplified (+), moderately amplified (++), or strongly amplified (+++), as described previously24 (Fig 1).

Amplified wt1-specific mRNA and β-actin–specific mRNA in AML blast cells (length of PCR product: 857 bp [wt1] and 652 bp [β-actin]). Lane 1, marker (100-bp ladder, Hind/EcoRI-digested λ DNA); lane 2, negative control; lane 3, positive control (cell line HEL 92.1.1); lanes 4 and 5, wt1-negative AML; lanes 6 and 7, wt1 low AMLs; lanes 8 and 9, wt1 intermediate AML; lanes 10 and 11, wt1 high AMLs. Amount of wt1-specific mRNA was determined by quantitative PCR: lanes 4 and 5, <0.0001 fg/μg total RNA; lane 6, 0.023 fg/μg; lane 7, 0.031 fg/μg; lane 8, 0.186 fg/μg; lane 9, 0.367 fg/μg; lane 10, 19.037 fg/μg; lane 11, 9.484 fg/μg.

Amplified wt1-specific mRNA and β-actin–specific mRNA in AML blast cells (length of PCR product: 857 bp [wt1] and 652 bp [β-actin]). Lane 1, marker (100-bp ladder, Hind/EcoRI-digested λ DNA); lane 2, negative control; lane 3, positive control (cell line HEL 92.1.1); lanes 4 and 5, wt1-negative AML; lanes 6 and 7, wt1 low AMLs; lanes 8 and 9, wt1 intermediate AML; lanes 10 and 11, wt1 high AMLs. Amount of wt1-specific mRNA was determined by quantitative PCR: lanes 4 and 5, <0.0001 fg/μg total RNA; lane 6, 0.023 fg/μg; lane 7, 0.031 fg/μg; lane 8, 0.186 fg/μg; lane 9, 0.367 fg/μg; lane 10, 19.037 fg/μg; lane 11, 9.484 fg/μg.

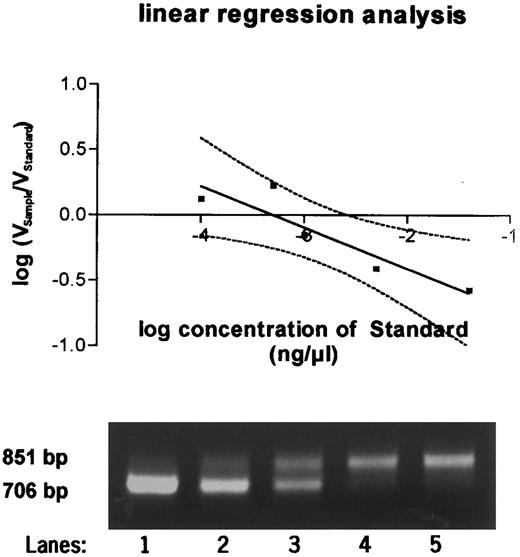

Competitive PCR.To establish a competitive PCR based on the method described by Becker-André and Hahlbrock,37 a competitor template serving as an internal standard was designed. Plasmid LK-15 containing the full-length wt1 cDNA (kindly provided by M. Gessler, Würzburg, Germany)2 was subcloned into pBluescript KS (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) downstream of the T7 promotor after Sac II/EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Schwalbach, Germany) digestion. Subsequently, the subclone was digested with Rsr II and Xcm I (New England Biolabs) to remove a 145-bp fragment, blunted with T4 polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), and religated. PCR of the shortened clone yielded in a band of 706 bp compared with a band of 851 bp using wild-type wt1 as template, allowing us to distinguish the products after amplification in the same PCR reaction.

To avoid quantitation errors arising from different reverse transcription efficiencies, competitor and sample were reverse transcribed in the same tube. For this purpose, the shortened clone was in vitro transcribed using the T7 RNA transcription kit (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany), digested with RNase-free DNase (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), and phenol-chloroform extracted. After photometrical quantitation of the transcribed RNA, which was repeated in three independent measurements to ensure validity, RNA was diluted in a logarithmic scale.

The same amount of total sample RNA (0.5 μL) was now reverse transcribed in five different reactions together with 1 μL containing 0.04 ng/μL, 0.005 ng/μL, 0.001 ng/μL, 0.5 pg/μL, and 0.1 pg/μL standard cRNA, respectively. The reverse transcription was performed according to the protocol described above with the only difference consisting in the use of a wt1 mRNA 3′-region specific primer (5′-TGTGCAAGGAGGTATGTACAT). PCR conditions were the same as described above. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and blotted subsequently.

To determine the exact amount of wt1-specific mRNA, the decadic logarithm of the quotient of volume of the probe and the standard was plotted against the decadic logarithm of the amount of standard RNA. Linear regression analysis was perfomed. At the point at which the regression curve intercepted the X-axis and ratio equaled 1, the amount of standard and of the sample were identical (Fig 2). The quantitation in femtograms was calculated on the basis of 1 μg total RNA.

Quantitative PCR products using a competitor template serving as an internal standard run on a 2% agarose gel. Equal amounts of sample RNA were reverse transcribed together with 0.04 ng (lane 1), 0.005 ng (lane 2), 0.001 ng (lane 3), 0.0005 ng (lane 4), and 0.0001 ng (lane 5) of wt1 standard cRNA and amplified by PCR. PCR products were quantitated after Southern blotting, and the equivalence point of sample RNA (851 bp) and standard RNA (706 bp) was determined by regression analysis as shown in the graph above.

Quantitative PCR products using a competitor template serving as an internal standard run on a 2% agarose gel. Equal amounts of sample RNA were reverse transcribed together with 0.04 ng (lane 1), 0.005 ng (lane 2), 0.001 ng (lane 3), 0.0005 ng (lane 4), and 0.0001 ng (lane 5) of wt1 standard cRNA and amplified by PCR. PCR products were quantitated after Southern blotting, and the equivalence point of sample RNA (851 bp) and standard RNA (706 bp) was determined by regression analysis as shown in the graph above.

Southern blot analysis.Southern blots were performed to quantitate PCR products as well as to ensure their integrity. Electrophoresed PCR products were blotted on nylon membrane (GeneScreen; NEN, Boston, MA), as previously described.38 Gels were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes with 0.25 mol/L HCl, for 30 minutes in 1.5 mol/L NaCl/0.5 mol/L NaOH, and finally for 15 minutes in 1.5 mol/L NaCl/0.25 mol/L NaOH and transferred on nylon membrane overnight by capillary blotting. After prehybridization for 1 hour, hybridization was performed with an α-P32–labeled 593-bp DNA fragment that was derived from digestion of LK-15 (kindly provided by M. Gessler, Würzburg, Germany) with BamHI and Rsr II at 55°C overnight in 1 mmol/L EDTA, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.25 mol/L disodium phosphate, pH 7.2, using 2 pmol/mL wt1-specific probe. Labeling was performed using the Rediprime Kit (Amersham, Heidelberg, Germany). Subsequently, the membrane was washed twice in 2× SSC/1.0% SDS at room temeperature for 5 minutes and then twice in 1× SSC/1.0% SDS at 55°C for 15 minutes. A final wash in 1× SSC was performed twice for 5 minutes at room temperature. The blot was exposed on a PhosphorImager SI (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and quantitated using the Image-Quant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Statistics.Overall survival was calculated from the beginning of treatment until death, and the leukemia-free survival (LFS) was calculated from time of CR has been achieved until relapse. The survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method.39 The log-rank test was used to assess the significance of differences in survival.40 Fisher's exact test was used to analyze contingency tables of response in association with wt1 mRNA expression. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U-test and χ2 test were used to calculate significant differences of wt1 mRNA expression or remission rates between various groups. Additionally, Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors was performed.

RESULTS

Expression of wt1 in acute leukemias.Total mRNA from 129 patients with newly diagnosed AML (114 de novo and 15 with antecedent myelodysplastic syndromes [MDS]) and 32 patients in first relapse were reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified using wt1-specific oligonucleotides. The sensitivity of the wt1-specific reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was found to be about 1 wt1 positive cell of 104 to 105 negative cells.24 The amplification of the β-actin gene was used as an internal control. To confirm the specificity of the PCR products, Southern blotting was performed. The ethidium bromide stained and photographed PCR products were visually classified into not amplified (−), weakly amplified (+), moderately amplified (++), and strongly amplified (+++), as described previously.24 This quantitation was confirmed by competitive PCR, as shown in Fig 2. Not amplified PCR products were below the detection limit (<0.001 fg specific RNA of 1 μg total RNA), the (+) classified PCR products corresponded to 0.09 fg (±0.11) RNA of 1 μg total RNA, the (++) to 0.85 fg (±0.45), and the (+++) to 8.92 fg (±7.8). The wt1-specific mRNA content was about 1 to 2 log10 higher in moderately and strongly amplified products than in the others. Therefore, AMLs with no or weakly detectable wt1 signals and those with moderate and strong wt1 levels were summarized as one group each for survival analyses.

Totally, wt1 mRNA expression was found in in 77% of all 161 studied samples (Table 1). The frequency of wt1 expression between de novo AML and AML with antecedent MDS did not differ. Only in patients in first relapse a slightly higher incidence of wt1 mRNA (87.5% v 74.6%) was found (Table 1). There was no relationship concerning the FAB subtype of AML and wt1 expression except in M5 AMLs, which expressed wt1 mRNA in only 40.0% of the patients versus 79.8% in all other de novo AMLs (P = .0025).

wt1 Expression in AML According to FAB Subtype and Age

| . | wt1+ Patients . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| AML, total* | 124/161 | 77.0 |

| AML, de novo | 85/114 | 74.6 |

| AML, after MDS | 11/15 | 73.3 |

| AML, first relapse* | 28/32 | 87.5 |

| FAB subtype of de novo AML | ||

| M0 | 3/3 | 100.0 |

| M1 | 8/9 | 88.9 |

| M2 | 29/39 | 74.4 |

| M3 | 7/8 | 87.5 |

| M4 | 28/36 | 77.8 |

| M5† | 6/15 | 40.0 |

| M6 | 3/3 | 100.0 |

| ND | 1/1 | |

| Age <60 yr | 70/92 | 76.1 |

| Age >60 yr | 36/47 | 76.6 |

| . | wt1+ Patients . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| AML, total* | 124/161 | 77.0 |

| AML, de novo | 85/114 | 74.6 |

| AML, after MDS | 11/15 | 73.3 |

| AML, first relapse* | 28/32 | 87.5 |

| FAB subtype of de novo AML | ||

| M0 | 3/3 | 100.0 |

| M1 | 8/9 | 88.9 |

| M2 | 29/39 | 74.4 |

| M3 | 7/8 | 87.5 |

| M4 | 28/36 | 77.8 |

| M5† | 6/15 | 40.0 |

| M6 | 3/3 | 100.0 |

| ND | 1/1 | |

| Age <60 yr | 70/92 | 76.1 |

| Age >60 yr | 36/47 | 76.6 |

In M5 AMLs the frequency of wt1 expression was significantly reduced (P < 0.0025). The weakly positive wt1 patients were grouped with the wt1-positive patients.

Abbreviation: ND, not defined.

Twenty-two patients included were investigated at the time of diagnosis and first relapse.

P < .0025.

Additionally, the distribution of AMLs with different levels of wt1 expression was similar regarding the age and the FAB subtype, with the described exception of M5 AMLs and the age. However, the wt1 mRNA expression was associated with the phenotypical characteristics of blast cells. AMLs with a high proportion of CD34+ blasts or with a lower proportion of CD33+ blasts were significantly associated with no or low levels of wt1 mRNA (Table 2). Other surface antigens, such as CD19, CD15, CD7, and CD11c, did not correlate with the wt1 mRNA expression (Table 2). In regards to the cytogenetic analyses, there was no major difference in the frequency of wt1 expression concerning favorable or unfavorable cytogenetic aberrations (Table 2).

Expression Levels of wt1 mRNA in Relation to Response to Therapy, Phenotype, and Karyotype of the AMLs

| Wt1 Expression . | Total . | 0/+ . | ++/+++ . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRall | 91/139 (65) | 49/71 (69) | 42/68 (62) | NS |

| CRde novo | 76/114 (67) | 42/59 (71) | 34/55 (62) | NS |

| CD34 >37% | 65 | 40 (62) | 25 (38) | |

| CD34 <37% | 58 | 48 (48) | 38 (52) | .036 |

| CD15 >38% | 62 | 35 (56) | 27 (44) | |

| CD15 <38% | 64 | 29 (45) | 35 (55) | NS |

| CD33 >92% | 62 | 24 (39) | 38 (61) | |

| CD33 <92% | 69 | 44 (64) | 25 (36) | .005 |

| CD11c >35% | 62 | 28 (45) | 34 (55) | |

| CD11c <35% | 63 | 36 (57) | 27 (43) | NS |

| CD19 >25% | 59 | 28 (47) | 31 (53) | |

| CD19 <25% | 60 | 30 (50) | 30 (50) | NS |

| CD7 >19% | 65 | 34 (52) | 31 (48) | |

| CD7 <19% | 64 | 30 (47) | 34 (53) | NS |

| Favorable karyotype* | 10 | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | |

| Normal karyotype | 27 | 14 (52) | 13 (48) | |

| Unfavorable karyotype† | 22 | 16 (73) | 6 (27) | NS |

| Wt1 Expression . | Total . | 0/+ . | ++/+++ . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRall | 91/139 (65) | 49/71 (69) | 42/68 (62) | NS |

| CRde novo | 76/114 (67) | 42/59 (71) | 34/55 (62) | NS |

| CD34 >37% | 65 | 40 (62) | 25 (38) | |

| CD34 <37% | 58 | 48 (48) | 38 (52) | .036 |

| CD15 >38% | 62 | 35 (56) | 27 (44) | |

| CD15 <38% | 64 | 29 (45) | 35 (55) | NS |

| CD33 >92% | 62 | 24 (39) | 38 (61) | |

| CD33 <92% | 69 | 44 (64) | 25 (36) | .005 |

| CD11c >35% | 62 | 28 (45) | 34 (55) | |

| CD11c <35% | 63 | 36 (57) | 27 (43) | NS |

| CD19 >25% | 59 | 28 (47) | 31 (53) | |

| CD19 <25% | 60 | 30 (50) | 30 (50) | NS |

| CD7 >19% | 65 | 34 (52) | 31 (48) | |

| CD7 <19% | 64 | 30 (47) | 34 (53) | NS |

| Favorable karyotype* | 10 | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | |

| Normal karyotype | 27 | 14 (52) | 13 (48) | |

| Unfavorable karyotype† | 22 | 16 (73) | 6 (27) | NS |

The cut-off for the expression of surface antigens on blast cells was calculated by the median of all measured percentages. The total number of patients varies due to differences in available immunophenotyping. Values are the number of patients with percentages in parentheses.

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

inv(16), t(8/21), t(15/17).

Chromosomal aberrations other than those listed above.

wt1 expression and outcome.To evaluate a possible prognostic relevance of wt1 mRNA expression, we correlated the wt1 expression at time of diagnosis with the response to therapy, disease-free survival, and overall survival. There was no statistically significant association between the detection of wt1 gene transcripts before treatment and the achievement of CRs, but a tendency towards higher CR rates in low wt1 mRNA expressing AMLs with a CR rate of 73% in wt1 negative, 66% in wt1 weakly positive, and 62% in wt1 strongly positive patients (Table 2).

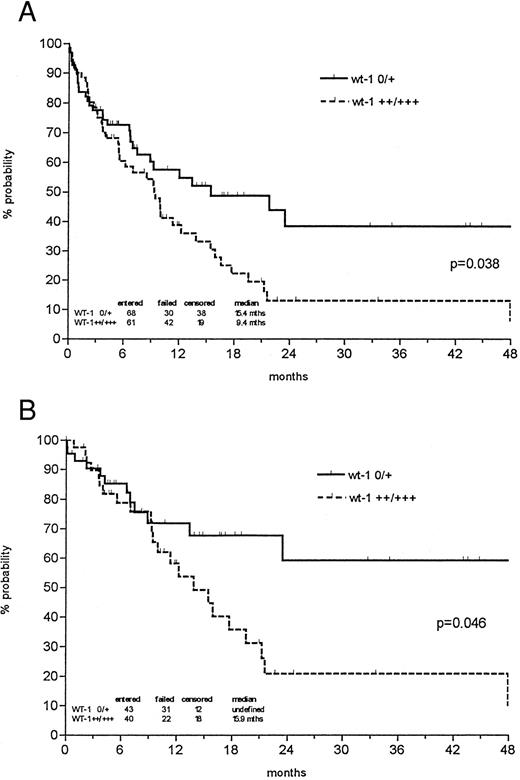

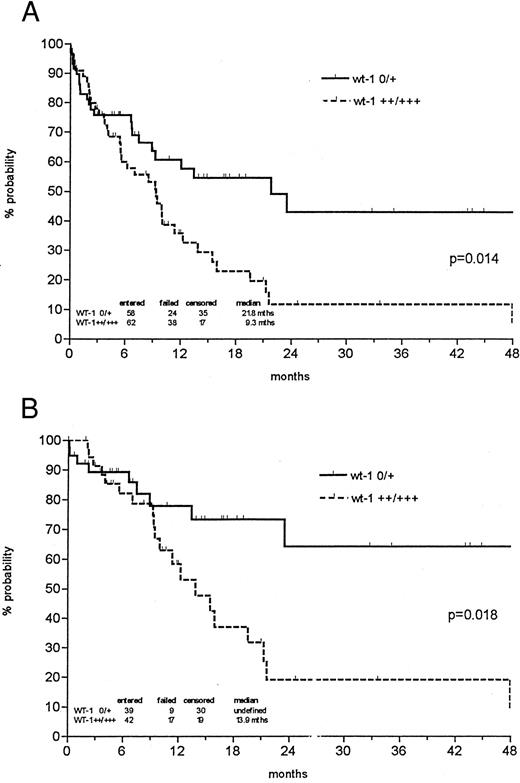

The probability of 1- and 3-year survival was 48% and 24% for all newly diagnosed AMLs, respectively, with a median follow-up of 27.5 months. However, the probability of 3-year overall survival was 38% in the patient group expressing low levels of wt1 mRNA versus 13% in the group with strong wt1 signals (P = .038; Fig 3). In patients less than 60 years of age, low wt1 expression levels corresponded to a 59% overall survival versus 21% in the group expressing high levels of wt1 (P = .046). Analyzing only the de novo AMLs, the discrimination of prognostic groups seemed even more distinctive, with a probability of 3-year survival of 43% versus 12% (P = .014) and 64% versus 19% in patients less than 60 years of age (P = .018; Fig 4).

Probability of overall survival in all newly diagnosed AML patients (A) and those less than 60 years of age (B) according to Kaplan-Meier calculation in relation to wt1 mRNA (no or weak v intermediate or strong) expression at time of diagnosis. Both de novo AMLs and AMLs with antecedent MDS were included. Patients undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) were censored at the time of BMT.

Probability of overall survival in all newly diagnosed AML patients (A) and those less than 60 years of age (B) according to Kaplan-Meier calculation in relation to wt1 mRNA (no or weak v intermediate or strong) expression at time of diagnosis. Both de novo AMLs and AMLs with antecedent MDS were included. Patients undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) were censored at the time of BMT.

Probability of overall survival of all de novo AML patients (A) and those less than 60 years of age (B) according to Kaplan-Meier calculation in relation to wt1 mRNA (no or weak v intermediate or strong) expression at the time of diagnosis. Patients undergoing allogeneic BMT were censored at the time of BMT.

Probability of overall survival of all de novo AML patients (A) and those less than 60 years of age (B) according to Kaplan-Meier calculation in relation to wt1 mRNA (no or weak v intermediate or strong) expression at the time of diagnosis. Patients undergoing allogeneic BMT were censored at the time of BMT.

The LFS depended on the level of wt1 expression, too, but, due to limited patient numbers, the difference was not yet significant. The probability of 3-year LFS for all newly diagnosed AML patients with no or low wt1 mRNA expression was 51% versus 29% in patients with high wt1 levels and in de novo AMLs less than 60 years of age the LFS was 63% versus 33% (P = .09). Cox regression analysis showed wt1 to be a prognostic factor independent from age and cytogenetics.

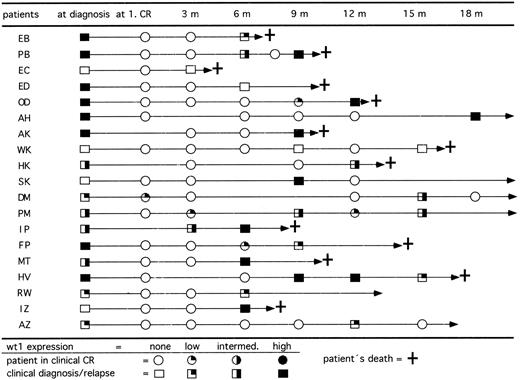

wt1 expression in course of CR.In 77 patients we studied the expression levels of wt1 mRNA during follow-up. All patients who were previously wt1 mRNA positive at diagnosis became negative after achieving CR. To evaluate the relevance of wt1 mRNA expression for early detection of relapses, only those 50 patients with 3 or more follow-up analyses for wt1 mRNA were included. At diagnosis, 37 of these patients showed detectable wt1 transcripts and 13 patients were negative. Up to now, 15 previously wt1-positive patients relapsed (Fig 5). The blasts of 14 of 15 patients (93%) expressed wt1 again. On the other hand, 4 of 13 previously wt1-negative patients relapsed. Two patients remained wt1 negative, but 2 patients converted to high levels of wt1 mRNA. The occurrence of wt1 transcripts in CR indicated a following relapse up to 3 months before morphologically detectable relapse. To address the question of whether the detection of wt1 transcripts may be caused by enriched normal CD34+ precursor cells, the wt1 mRNA was quantitated by competitive PCR. The data showed that the wt1 mRNA is only transiently expressed in normal CD34+ cells during early phase of differentiation.30

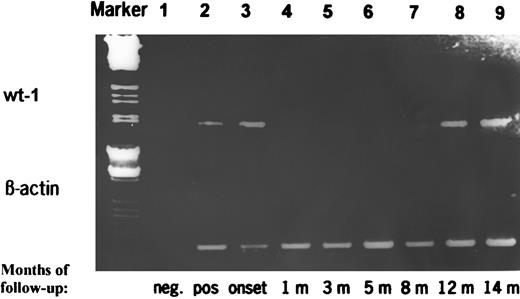

Follow-up of RT-PCR products for wt1 in 19 patients who relapsed after achieving clinical CR. Fourteen of 15 patients initially wt1 positive reexpressed wt1 mRNA in relapse and 2 of 4 patients initially wt1 negative became wt1 positive in relapse. Patients SK and AZ relapsed and achieved a second CR by reinduction therapy.

Follow-up of RT-PCR products for wt1 in 19 patients who relapsed after achieving clinical CR. Fourteen of 15 patients initially wt1 positive reexpressed wt1 mRNA in relapse and 2 of 4 patients initially wt1 negative became wt1 positive in relapse. Patients SK and AZ relapsed and achieved a second CR by reinduction therapy.

The follow-up data in two representative cases were confirmed by a competitive PCR assay as shown in Fig 6. The specific mRNA transcripts corresponded very well to the intensity of the PCR product. The results calculated by evaluation of our competitive PCR assay corresponded well to the visual classification of the ethidium bromide-stained PCR products.

RT-PCR products of wt1 during follow-up of a patient with AML achieving CR and who relapsed 14 months later. The PCR products were additionally quantitated by a competitive PCR. Marker, HindIII/EcoRI-digested λ DNA; lane 1, negative control; lane 2, positive control; lane 3, de novo AML at diagnosis (19.0371 fg wt1-specific mRNA/μg total RNA); lanes 4 through 7, AML in CR (wt1 mRNA <0.0001 fg/μg); lane 8, AML in clinical and morphological CR but positive PCR (quantitation due to limited amount of RNA not done); and lane 9, clinical and morphological relapse of AML (9.484 fg/μg).

RT-PCR products of wt1 during follow-up of a patient with AML achieving CR and who relapsed 14 months later. The PCR products were additionally quantitated by a competitive PCR. Marker, HindIII/EcoRI-digested λ DNA; lane 1, negative control; lane 2, positive control; lane 3, de novo AML at diagnosis (19.0371 fg wt1-specific mRNA/μg total RNA); lanes 4 through 7, AML in CR (wt1 mRNA <0.0001 fg/μg); lane 8, AML in clinical and morphological CR but positive PCR (quantitation due to limited amount of RNA not done); and lane 9, clinical and morphological relapse of AML (9.484 fg/μg).

DISCUSSION

The Wilms' tumor gene (wt1) has been shown to be expressed in the majority of patients with AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and blast crisis of CML.22-26 The wt1 translated gene product is a nuclear protein and has been detected by immunofluorescence techniques in about 60% of acute leukemias.25 In normal bone marrow, wt1 transcripts were not detectable by our RT-PCR assay. Using a more sensitive PCR approach and subsequent Southern blotting, wt1 transcripts could be detected in normal bone marrow, too. In this context, we showed that normal CD34+ cells expressed wt1 transiently during early hematopoietic differentiation.26,30 These data, the observation of wt1 mRNA down-regulation during differentiation in leukemic cell lines, and the induction of differentiation by blocking wt1 transcription via antisense suggest that wt1 is indeed involved in the differentiation of hematopoetic precursor cells and possibly in leukemogenesis.28-30 41

The present study showing that in 124 of 161 (77%) samples of patients with AML at diagnosis mRNA for wt1 was detected by PCR confirms the recently published data of wt1 expression in AML; however, different frequencies published may result from different detection methods.22,24,26 Interestingly, in M5 FAB leukemias, wt1 transcripts were significantly less frequent than in the other subtypes (40% v 79%, P = .0025). This is in accordance with the data of Miwa et al22 suggesting a loss of wt1 in more mature leukemias and with the downregulation of wt1 during differentiation in vitro described above. There was a slightly higher incidence of wt1 mRNA in relapsed patients, but no difference regarding age and or de novo AMLs or AMLs with antecedent MDS. However, high levels of wt1 transcripts are associated with a lower expression of CD34 and higher expression of CD33 on blast cells. This observation seems to be in contrast to the data in normal hematopoietic differentiation, which suggest that the downregulation of wt1 is associated with the upregulation of CD33 on CD34+ precursor cells.29 Therefore, the persistence of wt1 in CD33+ AMLs may indicate a possible role of this gene in leukemogenesis.

In accordance with the data of Inoue et al,42 patients with high wt1 levels had lower CR rates than those with low or not detectable wt1 transcripts. Regarding the relevance of wt1 for survival, the data show that initially high expression of wt1 mRNA is significantly associated with a worse long-term outcome concerning overall survival and LFS. This difference is more distinct in patients less than 60 years of age than in older patients, suggesting age to be an independent factor for long-term outcome. Similar data concerning the long-term outcome have been described by Inoue et al42 for a common analysis of AMLs and ALLs. The reason for association of high wt1 expression with a worse long-term outcome remains speculative. One hint for the pathophysiological relevance of wt1 may be the data of Yamagami et al,41 who showed that leukemic growth was inhibited in vitro by reduction of Wt1 protein production via wt1 antisense, demonstrating an association between high wt1 levels and leukemic growth. Another explanation is given by possible interactions of wt1 with the bcl-2 gene and its involvement in the inhibition of apoptosis induced by cytostatic agents.43,44 Here, preliminary data show that wt1 mRNA expression is also associated with bcl-2 mRNA expression in AML resulting in a highly significant prognostic score for AML patients.44

In AMLs, some chromosomal aberrations have been described to be associated with prognosis. The most common abnormalities are a gain of chromosome 8 and a loss of chromosome 7 accounting for approximately 20% found in AML, whereas other aberrations are rare and most patients impose with a normal karyotype. An important problem for the success of chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation is the detection of minimal residual disease (MRD). Here, the various chromosomal aberrations may be used for detection of MRD on an individual basis, but they cannot generally be used as a common marker for AMLs because each of these various genetic markers occur only in a small proportion of AMLs.45 In contrast, wt1 is expressed in about 75% to 80% of all AMLs.

Therefore, wt1 expression may be useful for early prediction of relapse. The sensitivity of dectection of wt1 mRNA by PCR was 1 of 104 to 105 cells. Subsequent analyses of wt1 transcripts during follow-up indicate that wt1 mRNA analysis may be useful as a marker for MRD.42,46 On the basis of 50 patients with at least 3 follow-ups, we demonstrated that all patients achieving CR became negative for wt1 latest after regeneration after the first consolidation chemotherapy, whereas persistance of wt1 indicated treatment failure.42 46 Additionally, reoccurrence of wt1 in CR patients predicted a clinical relapse after a few weeks to up to 3 months later.

In a few patients, wt1 reappeared intermittently with very low or even borderline levels of wt1 mRNA. The significance of these observations for long-term remission is not yet defined. Intermittent reappearance of low wt1 levels possibly indicates minimal residual blasts populations controlled by autologous antileukemic effects.32 47

However, the relevance of wt1 mRNA expression for monitoring of MRD has still to be evaluated. But recently, Inoue et al48 confirmed the prognostic relevance of wt1 mRNA monitoring in bone marrow or peripheral blood for long-term follow-up and prediction of relapse. However, the question of possible wt1 expression in normal hematopoietic precursor cells has to be addressed, as we and others30,46,49 found that normal CD34+ precursor cells express wt1 mRNA, too. Thus, the relevance for detecting MRD may be questionable, especially for low wt1 expressing AMLs. On the other side, Inoue et al42 found significantly lower levels of wt1 transcripts by a semiquantitive PCR in normal bone marrow than in acute leukemias. Additionally, all CR patients with reoccurrence of wt1 mRNA during follow-up relapsed.

In conclusion, the reported data strongly suggest a clinical relevance of wt1 mRNA expression for the long-term outcome in AMLs. Analysis of wt1 expression accompanying routine bone marrow aspirations may be useful to predict prognosis besides cytogenetic findings and to define the quality of remission and early prediction of relapse of the disease. Whether wt1 may be a useful marker for detection of MRD as well as its potential role in the pathogenesis of acute leukemias has to be elucidated by further trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the excellent technical support of Susanne Christ, Stephanie Finkler, Bettina Kalt, and Bernd Schneider and thank Dr H. Ackermann for biostastic analysis.

Address reprint requests to Lothar Bergmann, MD, Medical Clinic III, J.W. Goethe University, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt/M, Germany.

![Fig. 1. Amplified wt1-specific mRNA and β-actin–specific mRNA in AML blast cells (length of PCR product: 857 bp [wt1] and 652 bp [β-actin]). Lane 1, marker (100-bp ladder, Hind/EcoRI-digested λ DNA); lane 2, negative control; lane 3, positive control (cell line HEL 92.1.1); lanes 4 and 5, wt1-negative AML; lanes 6 and 7, wt1 low AMLs; lanes 8 and 9, wt1 intermediate AML; lanes 10 and 11, wt1 high AMLs. Amount of wt1-specific mRNA was determined by quantitative PCR: lanes 4 and 5, <0.0001 fg/μg total RNA; lane 6, 0.023 fg/μg; lane 7, 0.031 fg/μg; lane 8, 0.186 fg/μg; lane 9, 0.367 fg/μg; lane 10, 19.037 fg/μg; lane 11, 9.484 fg/μg.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/3/10.1182_blood.v90.3.1217/4/m_bl_0030f1.jpeg?Expires=1769305375&Signature=2IFLyJKNq-DBPAT3MgLvTqwKMCR3PS6riEQaJOM8uCozZjwSTKSnPhEUSxnEsshFTGeDqOSkZTMRbDVswInoRHyctQqMPtUamMyqG6xZgyiMfGOTyD193SZNUex50GzGC9lJ-bIrRaz4JyksFDKJO0~cIOY0n3E5FDwrDDJlF8QCss9-9Z-tI2vllYDtDQouRQvfXBXn1e4yEIdQxzzEQgkAIoyNTUft8r8MW3w0JTEK9i1YjvU~horSQ-xTzGCp2SvYObsV9eK162scVhxpJqnWEf22oPw-y0xSEIaajf4HUGn3KW8EPtXNFPcz4HS0mKpHJ0dNXN6DICIaWzuQDQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal