Abstract

Thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the treatment of malignant disease. Recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF ) is a potent stimulator of megakaryocytopoiesis and prevents chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia in preclinical studies. We administered PEG-rHuMGDF with filgrastim after dose-intensive chemotherapy to 41 patients with advanced cancers to determine its safety and effects on hematologic recovery. Carboplatin 600 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 1,200 mg/m2 were administered to patients with advanced cancer. Patients were randomly assigned to receive blinded study drug, either PEG-rHuMGDF or placebo (3-to-1 ratio), commencing the day after chemotherapy. PEG-rHuMGDF was given at doses of 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 μg per kilogram body weight by daily subcutaneous injection for between 7 and 20 days. All patients received concurrent filgrastim 5 μg per kilogram body weight per day until neutrophil recovery. Fifteen patients had received PEG-rHuMGDF alone in a previous phase I study. Platelet function and peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) were assessed. PEG-rHuMGDF enhanced platelet recovery in a dose-related manner when compared with placebo. The platelet nadir occurred earlier in patients given PEG-rHuMGDF (P = .002) but there was no difference in the depth of the nadir. Recovery to baseline platelet count was achieved significantly earlier following PEG-rHuMGDF administration compared with placebo (median, 17 days for PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg versus 22 days for placebo, P = .014). In addition, platelet recovery was faster in patients who had previously received PEG-rHuMGDF, suggesting that pretreatment might be beneficial. Platelet function did not change during or after administration of PEG-rHuMGDF. Levels of PBPC on day 15 after chemotherapy were significantly greater in patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg and filgrastim compared with those given placebo plus filgrastim. PEG-rHuMGDF was well tolerated at all doses. Two patients given PEG-rHuMGDF had a thrombotic episode. PEG-rHuMGDF accelerates platelet recovery after moderately dose-intensive carboplatin and cyclophosphamide, and is likely to be clinically useful in treatment of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia. Because it enhances mobilization of PBPC by filgrastim, PEG-rHuMGDF might also allow more efficient collection of stem cells for autologous or allogeneic transplantation.

THE EFFECTIVENESS of chemotherapy for many types of cancers is related to the dose administered.1-3 Although the ability of myeloid colony-stimulating factors to abrogate neutropenia4,5 has allowed exploration of dose-intensive regimens, thrombocytopenia becomes the dose-limiting toxicity after only modest increases in chemotherapy. Clinical studies with interleukin-1 (IL-1),6 IL-6,7 and IL-118 have shown that these agents can reduce chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia, but the pleiotropic activities of these molecules produce a number of unwanted adverse effects.

Pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF ) is a nonglycosylated, truncated form of human thrombopoietin (Mpl ligand) that is conjugated with polyethylene glycol.9,10 Thrombopoietin is the central physiologic regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production.11 Preclinical studies have shown that PEG-rHuMGDF is a potent lineage-dominant megakaryocyte colony-stimulating factor (CSF ) that also induces endomitosis, maturation, and terminal differentiation of immature megakaryocytes in vitro.12,13 In addition, it abrogates chemotherapy- and radiation-induced thrombocytopenia.9,12,14,15 In a previous phase I study, we showed that PEG-rHuMGDF caused a dose-related increase in platelets with minimal toxicity when administered to patients with advanced cancer.16

We conducted a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study to test the safety and hematologic effects of PEG-rHuMGDF in patients with advanced cancer receiving dose-intensive carboplatin and cyclophosphamide supported by filgrastim. These cytotoxic agents are active against a broad range of cancers17-20 and have increased activity with increasing dose.21,22 Furthermore, escalation of the doses of carboplatin and cyclophosphamide is limited by thrombocytopenia when the combination is administered with filgrastim.23 Because of preclinical data suggesting an effect of PEG-rHuMGDF on platelet aggregation,15,24 25 we assessed the functional characteristics of platelets produced during and after administration of PEG-rHuMGDF. In addition, we evaluated whether PEG-rHuMGDF influenced the mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) induced by chemotherapy and filgrastim.

Baseline Characteristics of 41 Patients With Advanced Cancer Administered Placebo Plus Filgrastim or PEG-rHuMGDF Plus Filgrastim After Chemotherapy

| . | Placebo . | PEG-rHuMGDF . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 10 | 31 |

| Median age (range) | 59 (36-69) | 57 (20-74) |

| Male/Female | 7/3 | 22/9 |

| Median Karnofsky performance status (range) | 85 (70-100) | 90 (60-100) |

| Tumor type | ||

| Non–small cell lung | 3 | 12 |

| Carcinoma of unknown primary | 2 | 4 |

| Gastric | 2 | 2 |

| Kidney | 1 | 2 |

| Small cell lung | 1 | 1 |

| Carcinoid | 1 | 0 |

| Other* | 0 | 10 |

| Prior chemotherapy | 1 | 6 |

| Prior radiotherapy | 1 | 5 |

| Median (range) baseline platelet count × 109/L | 270 (139-370) | 273 (148-487) |

| . | Placebo . | PEG-rHuMGDF . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 10 | 31 |

| Median age (range) | 59 (36-69) | 57 (20-74) |

| Male/Female | 7/3 | 22/9 |

| Median Karnofsky performance status (range) | 85 (70-100) | 90 (60-100) |

| Tumor type | ||

| Non–small cell lung | 3 | 12 |

| Carcinoma of unknown primary | 2 | 4 |

| Gastric | 2 | 2 |

| Kidney | 1 | 2 |

| Small cell lung | 1 | 1 |

| Carcinoid | 1 | 0 |

| Other* | 0 | 10 |

| Prior chemotherapy | 1 | 6 |

| Prior radiotherapy | 1 | 5 |

| Median (range) baseline platelet count × 109/L | 270 (139-370) | 273 (148-487) |

Includes ovary, thyroid, esophagus, liver, colon, melanoma, bladder, pancreas.

Study Drug and Filgrastim Administration for Each Patient Cohort

| Study Drug and Dose of PEG-rHuMGDF (μg/kg) . | No. Patients . | PEG-rHuMGDF Before Chemotherapy . | Days of PEG-rHuMGDF After Chemotherapy* . | Days of Filgrastim* . | No. of Patients Completing 2 Cycles of Chemotherapy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 10 | No | 0 | 12 (9-18) | 10 |

| 0.03 | 3 | Yes | 20 | 16 (11-19) | 2 |

| 0.1 | 3 | Yes | 20 | 12 (10-13) | 2 |

| 0.3 | 3 | Yes | 17 (15-20) | 10 (10-13) | 2 |

| 1.0 | 2 | Yes | 11, 20 | 11, 15 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 6 | No | 17 (15-19) | 14 (12-16) | 6 |

| 1.0 | 3 | No | 7 | 11 (10-21) | 3 |

| 3.0 | 7 | No | 7 | 10 (9-17) | 6 |

| 5.0 | 4 | No | 7 | 11 (10-12) | 4 |

| Study Drug and Dose of PEG-rHuMGDF (μg/kg) . | No. Patients . | PEG-rHuMGDF Before Chemotherapy . | Days of PEG-rHuMGDF After Chemotherapy* . | Days of Filgrastim* . | No. of Patients Completing 2 Cycles of Chemotherapy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 10 | No | 0 | 12 (9-18) | 10 |

| 0.03 | 3 | Yes | 20 | 16 (11-19) | 2 |

| 0.1 | 3 | Yes | 20 | 12 (10-13) | 2 |

| 0.3 | 3 | Yes | 17 (15-20) | 10 (10-13) | 2 |

| 1.0 | 2 | Yes | 11, 20 | 11, 15 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 6 | No | 17 (15-19) | 14 (12-16) | 6 |

| 1.0 | 3 | No | 7 | 11 (10-21) | 3 |

| 3.0 | 7 | No | 7 | 10 (9-17) | 6 |

| 5.0 | 4 | No | 7 | 11 (10-12) | 4 |

Median (range); when no range is given, patients received the stated duration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PatientsForty-one patients with advanced cancer received PEG-rHuMGDF or placebo after chemotherapy. Patients 18 years or older and with Karnofsky performance status of 60% or more were eligible. At entry, an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) at least 2.0 × 109/L, platelet count of 120 to 500 × 109/L and hemoglobin level of at least 90 g/L were required. Exclusion criteria included prior history of vascular disease or thromboembolism, significant heart, lung, liver (serum bilirubin >20 μmol/L), or renal (creatinine clearance less than 1.2 mL/s) impairment, prior treatment with melphalan, carmustine, lomustine, or mitomycin, and radiotherapy to more than 30% of the red bone marrow.

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committees of the participating hospitals. Each patient gave written informed consent before treatment.

Study design.Study drug treatment was randomized to either PEG-rHuMGDF (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 μg per kilogram body weight per day) or placebo in a ratio of 3:1 in cohorts of at least four patients per dose level. Fifteen patients had previously received PEG-rHuMGDF (n = 11) or placebo (n = 4) alone as part of an earlier study.16 This prechemotherapy phase also used a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled design, and these patients were given the same study drug and dose before and after chemotherapy (administered once platelet counts had returned to less than 500 × 109/L). All patients were administered carboplatin 600 mg/m2 followed by cyclophosphamide 1,200 mg/m2, both by intravenous infusion over 30 minutes on day 1. Study drug (PEG-rHuMGDF or placebo) was administered from day 2 by daily subcutaneous injection until a platelet count of more than 750 × 109/L or for 20 days, whichever occurred earlier (0.03-, 0.1-, 0.3-, and 1.0-μg/kg cohorts). The duration of study drug at the higher dose levels (1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 μg/kg) was shortened to 7 days because of asymptomatic thrombocytosis at lower doses of PEG-rHuMGDF. All patients received daily subcutaneous injections of filgrastim 5 μg/kg from the day after chemotherapy until an ANC of more than 10 × 109/L had been reached.

Patients were monitored daily for adverse effects. Vital signs were measured at regular intervals for 2 hours after each injection of blinded study drug, then daily until day 26 or until platelet counts returned to normal. Clinical examination was performed weekly. If there was no evidence of cancer progression, patients were able to receive further chemotherapy for up to six cycles at planned 28-day intervals. After the second and subsequent cycles patients were administered filgrastim as above but not PEG-rHuMGDF. Platelet transfusions were given for a platelet count of 20 × 109/L or less.

Blinding, randomization, and drug supply were as previously described.16 Investigators, all study site staff, and study monitors were blind to study drug assignment. Safety data were evaluated for a minimum of four patients enroled at each dose level before proceeding to the next dose level. Dose escalation was allowed if no patient experienced unacceptable World Health Organization (WHO) grade 2 or any grade 3 or 4 toxicity thought to be related to study drug.

PEG-rHuMGDF (Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA) has an amino acid sequence identical to the N-terminal 163 amino acids of native Mpl ligand, is covalently bonded with polyethylene glycol on the N-terminal, and supplied as a sterile, clear, aqueous solution.16 The placebo used in this study was identical to the vehicle for PEG-rHuMGDF.

Laboratory studies.After the first cycle of chemotherapy, complete blood counts were obtained daily for 21 days. If the platelet count was ≥500 × 109/L on day 21, complete blood counts were obtained every other day until platelets fell to within normal range or until the commencement of the second cycle of chemotherapy. Plasma chemistry values and coagulation parameters were measured weekly. Serum was taken for assay of antibodies to PEG-rHuMGDF at baseline and at the end of study. Serum was also collected and stored for future pharmacokinetic studies.

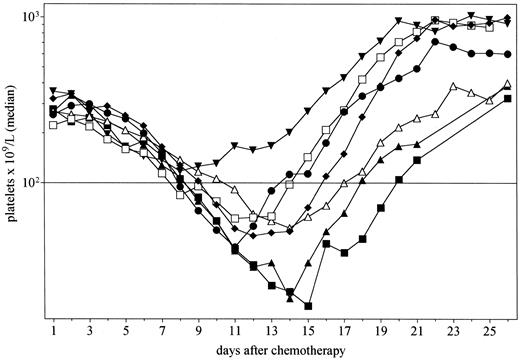

Median platelet counts after chemotherapy for patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg (▴, n = 6), 0.3 μg/kg (▾, n = 3), 1.0 μg/kg (♦, n = 11), 3.0 μg/kg (•, n = 7) or 5.0 μg/kg (□, n = 4), and placebo (▵, n = 10). The horizontal bar indicates a platelet count of 100 × 109/L.

Median platelet counts after chemotherapy for patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg (▴, n = 6), 0.3 μg/kg (▾, n = 3), 1.0 μg/kg (♦, n = 11), 3.0 μg/kg (•, n = 7) or 5.0 μg/kg (□, n = 4), and placebo (▵, n = 10). The horizontal bar indicates a platelet count of 100 × 109/L.

Blood was drawn for platelet aggregometry (agonists: adenosine diphosphate [ADP], collagen, TRAP1-6 , and ristocetin), adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release, and platelet surface marker studies (D3GP3, CD41a, CD42, CD61, and CD62P) using previously described methods26 at the following times: on day 1, before chemotherapy; on day 2, before the first dose of study drug; when platelets were more than 150 × 109/L after the nadir; within 24 hours of the last dose of study drug; and on day 26. Reticulated platelets (those most recently released from the marrow) were identified by staining with thiazole orange, which binds to mRNA,27 and were assessed at least three times per week. Samples was also taken weekly for assessment of blood progenitor cell levels.28

Patients who received a second cycle of chemotherapy had complete blood counts performed at least weekly, and at least three times weekly if the platelet count was less than 50 × 109/L.

Statistical analysis.Descriptive statistical analyses were performed for all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Data are expressed as medians (range) for continuous data and frequency (percentage) for categorical data, unless otherwise specified. Linear interpolation of data was used to estimate platelet counts on days when samples were not obtained. Descriptive (ie, not inferential) comparisons of PEG-rHuMGDF–treated patients with placebo patients were made using Fisher's Exact test for categorical data, the Mann Whitney U (rank sum) test for continuous data (SigmaStat; Jandel Software, San Rafael, CA), and Kaplan-Meier methods and the log-rank test (Prism; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) for platelet recovery. Where specified, data from PEG-rHuMGDF dose cohorts 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 μg/kg were pooled and compared with results from the placebo cohort to illustrate the effects of clinically active doses of PEG-rHuMGDF.

RESULTS

Patients.The characteristics of the 41 patients are listed in Table 1. Thirty-one patients were treated with PEG-rHuMGDF and 10 with placebo. The groups were well matched for age and sex. There was no difference in the number of patients who had received prior therapy for cancer. Dose cohort details are described in Table 2.

Hematologic toxicity and recovery.PEG-rHuMGDF at doses ≥0.3 μg/kg stimulated platelet recovery after chemotherapy. The median platelet counts after chemotherapy for patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg combined (n = 6), 0.3 μg/kg (n = 3), 1.0 μg/kg (n = 11), 3.0 μg/kg (n = 7), 5.0 μg/kg (n = 4), and placebo (n = 10) are shown in Fig 1. This shows that administration of PEG-rHuMGDF enhanced platelet recovery in a dose-related manner. Platelet recovery for patients administered doses of PEG-rHuMGDF previously shown not to elevate platelet counts (0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg)16 did not differ from placebo. There was no significant difference in the depth of the nadir between any of the cohorts, but, analogous to the effects of filgrastim on neutrophil nadir after chemotherapy,29 the platelet nadir occurred earlier in patients administered effective doses of PEG-rHuMGDF (0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg, 14.5 days; 0.3 μg/kg, 8 days; 1.0 μg/kg, 12 days; 3 μg/kg, 11 days; 5.0 μg/kg, 11.5 days; and placebo, 14.5 days).

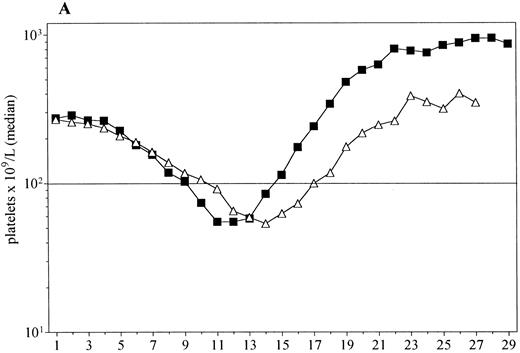

For further analysis, data from patients who received an effective dose of PEG-rHuMGDF (0.3, 1.0, 3.0, or 5.0 μg/kg) were combined. Median platelet counts for PEG-rHuMGDF patients and those given placebo are shown in Fig 2A. There was again no difference in the depth of the nadir between the two groups; however, it occurred significantly earlier in patients who received PEG-rHuMGDF (median day 12 [6-19] v day 14.5 [12-16], P = .002). Figure 2B shows a Kaplan-Meier analysis of probability of recovery to baseline (prechemotherapy) platelet count in the same groups of patients. Fifty percent of patients receiving PEG-rHuMGDF achieved baseline platelet counts by day 17, while this occurred at day 22 for the placebo cohort (P = .014).

(A) Platelet recovery for all patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF (▪, n = 25) and those given placebo (▵, n = 10). (B) The Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of recovery to baseline platelet counts in these groups. The median time to baseline counts was 18 days for PEG-rHuMGDF and 22 days for placebo (P = .02, log-rank test).

(A) Platelet recovery for all patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF (▪, n = 25) and those given placebo (▵, n = 10). (B) The Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of recovery to baseline platelet counts in these groups. The median time to baseline counts was 18 days for PEG-rHuMGDF and 22 days for placebo (P = .02, log-rank test).

Platelet recovery for five patients who received PEG-rHuMGDF before and after chemotherapy (0.3 μg/kg, n = 3; 1.0 μg/kg, n = 2) appeared to be more rapid than for nine patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 1.0 μg/kg only after chemotherapy. The time to baseline platelet counts was 16 days and 20 days, respectively. Although not statistically different, this observation raised the possibility that administration of PEG-rHuMGDF before chemotherapy may further enhance platelet recovery. There was no difference between placebo and PEG-rHuMGDF–treated patients in the number of individuals requiring a platelet transfusion (2 of 10 v 9 of 31; P = .7).

Asymptomatic thrombocytosis of more than 1,000 × 109/L platelets occurred during hematologic recovery in 11 patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF (peak 1,014 to 2,656 × 109/L) but in no placebo patients. The peak platelet count occurred up to 20 days after ceasing PEG-rHuMGDF. For patients who received PEG-rHuMGDF between 0.3 and 5.0 μg/kg, those given 7 days (n = 14) had a lower peak platelet count than those (n = 11) who had more prolonged administration (median 657 × 109/L v 1,126 × 109/L, P = .009).

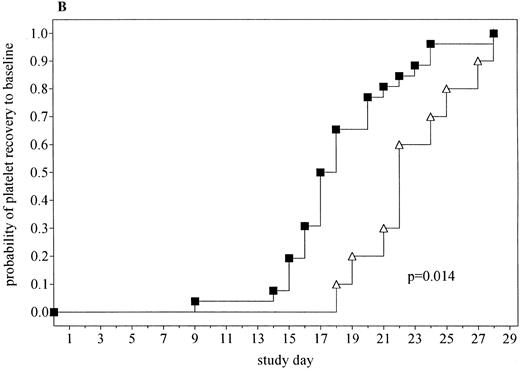

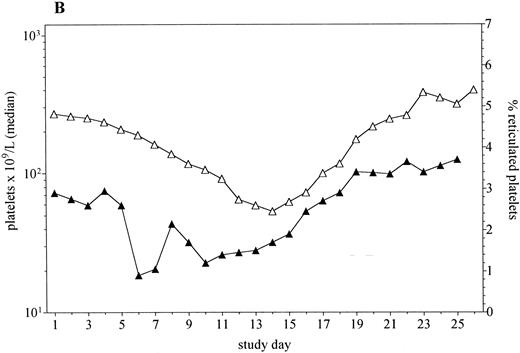

Platelet recovery in patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF at doses of 0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg was preceded by the early release of young (reticulated) platelets (Fig 3). The peak in the proportion of all platelets that were reticulated was greater in patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF than those receiving placebo (9% v 5%, P = .03). In addition, the peak in reticulated platelets occurred earlier in the PEG-rHuMGDF–treated patients (15 days v 21.5 days after chemotherapy, P = .003).

The median platelet counts and percentage reticulated platelets in patients receiving doses of PEG-rHuMGDF that enhanced platelet recovery (0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg, n = 25, A) and placebo (n = 10, B).

The median platelet counts and percentage reticulated platelets in patients receiving doses of PEG-rHuMGDF that enhanced platelet recovery (0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg, n = 25, A) and placebo (n = 10, B).

Severe neutropenia, generally of short duration, was observed in all dose cohorts (Table 3). There was no difference between placebo and effective doses of PEG-rHuMGDF in terms of neutrophil nadir (median 0.05 × 109/L v 0.06 × 109/L, respectively; P = .79), duration of neutrophil count less than 1.0 × 109/L, and the time to recovery of neutrophil counts to baseline. There were several episodes of febrile neutropenia, but no difference in frequency between placebo and PEG-rHuMGDF. Hematocrit tended to decrease after chemotherapy (Table 3). This was comparable for all patient cohorts.

Hematologic Toxicity During the First Cycle of Chemotherapy in 35 Patients Who Received Filgrastim Plus Placebo or PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 μg/kg Through 5.0 μg/kg

| . | Placebo + Filgrastim (n = 10) . | PEG-rHuMGDF* + Filgrastim (n = 25) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days to baseline platelet count | 22 (18-28) | 17 (9-28) | .0143-151 |

| Days of ANC <1.0 × 109/L | 2 (0-10) | 3 (0-8) | .663-152 |

| Days to baseline ANC count | 12 (11-18) | 12 (11-27) | .963-151 |

| Patients with febrile neutropenia (n) | 1 | 4 | 1.0ρ |

| Maximum change in hematocrit | −8% (−17% to −4%) | −7% (−14% to 0%) | 0.123-152 |

| . | Placebo + Filgrastim (n = 10) . | PEG-rHuMGDF* + Filgrastim (n = 25) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days to baseline platelet count | 22 (18-28) | 17 (9-28) | .0143-151 |

| Days of ANC <1.0 × 109/L | 2 (0-10) | 3 (0-8) | .663-152 |

| Days to baseline ANC count | 12 (11-18) | 12 (11-27) | .963-151 |

| Patients with febrile neutropenia (n) | 1 | 4 | 1.0ρ |

| Maximum change in hematocrit | −8% (−17% to −4%) | −7% (−14% to 0%) | 0.123-152 |

Median (range) where given. Febrile neutropenia = temperature >38.2°C and ANC <1.0 × 109/L.

Recovery for all patients administered doses of PEG-rHuMGDF of 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, or 5.0 μg/kg.

Log-rank test.

Rank sum test.

ρ Fisher's Exact test.

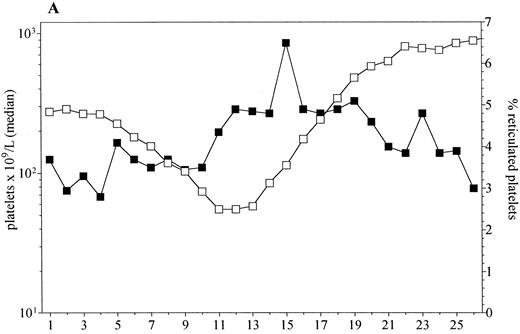

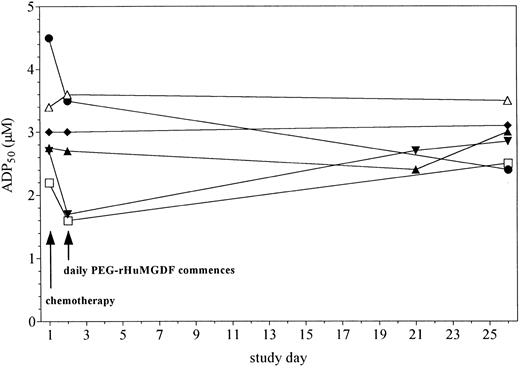

Platelet aggregation and surface marker analyses.Assays of platelet aggregation and ATP release to a variety of standard agonists26 were performed to assess platelet function during and after administration of study drug. There was no significant change in these parameters of platelet function in response to administration of either placebo or PEG-rHuMGDF at any of the time points tested. The concentration of ADP required to induce 50% maximum platelet aggregation for patients given placebo and PEG-rHuMGDF is shown in Fig 4. Analysis was performed of platelet surface expression of activation-dependent (CD41, CD61, CD62 [P-selectin], and D3GP3) and activation-independent (CD42) markers before and after chemotherapy. The level of expression remained unchanged in all patient groups.

Median concentration of ADP required to cause 50% maximum aggregation of platelets in vitro (ADP50 ) in patients receiving PEG-rHuMGDF rHuMGDF 0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg (▴, n = 6), 0.3 μg/kg (▾, n = 3), PEG-rHuMGDF 1.0 μg/kg (♦, n = 11), PEG-rHuMGDF 3.0 μg/kg (•, n = 3) PEG-rHuMGDF 5.0 μg/kg (□, n = 3), and placebo (▵, n = 7). Samples were taken before chemotherapy on day 1 and before PEG-rHuMGDF on day 2.

Median concentration of ADP required to cause 50% maximum aggregation of platelets in vitro (ADP50 ) in patients receiving PEG-rHuMGDF rHuMGDF 0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg (▴, n = 6), 0.3 μg/kg (▾, n = 3), PEG-rHuMGDF 1.0 μg/kg (♦, n = 11), PEG-rHuMGDF 3.0 μg/kg (•, n = 3) PEG-rHuMGDF 5.0 μg/kg (□, n = 3), and placebo (▵, n = 7). Samples were taken before chemotherapy on day 1 and before PEG-rHuMGDF on day 2.

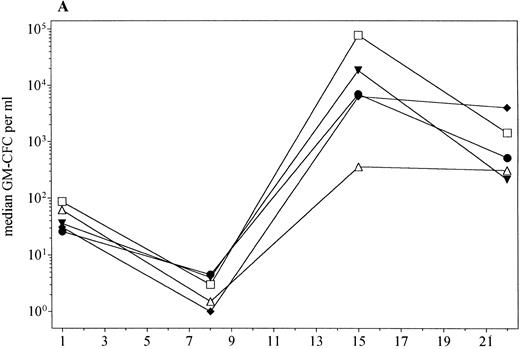

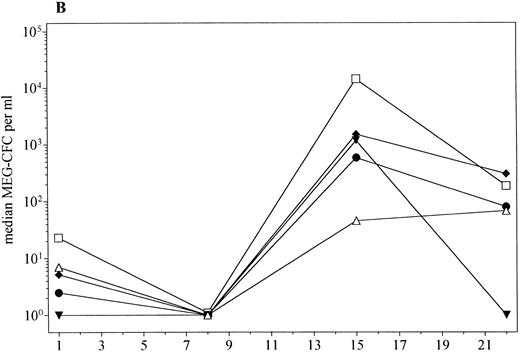

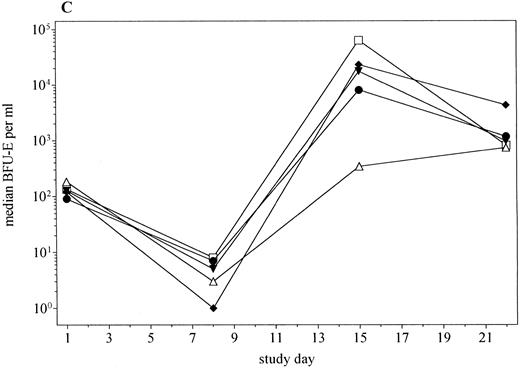

PBPC levels.Administration of PEG-rHuMGDF at doses of 0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg with filgrastim after chemotherapy significantly enhanced the mobilization of PBPC compared with filgrastim alone (Fig 5). In addition, there was a tendency for higher peak levels of PBPC with increasing doses of PEG-rHuMGDF. The fold increase in levels of PBPC from baseline to day 15 was significantly greater for patients receiving PEG-rHuMGDF plus filgrastim compared with those administered placebo plus filgrastim (Table 4).

PBPC mobilization (median) in patients receiving PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 (▾, n = 3), 1.0 μg/kg (♦, n = 11), 3.0 μg/kg (•, n = 7), or 5.0 μg/kg (□, n = 4), and placebo (▵, n = 10). (A) GM-CFC; (B) Meg-CFC; (C) BFU-E.

PBPC mobilization (median) in patients receiving PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 (▾, n = 3), 1.0 μg/kg (♦, n = 11), 3.0 μg/kg (•, n = 7), or 5.0 μg/kg (□, n = 4), and placebo (▵, n = 10). (A) GM-CFC; (B) Meg-CFC; (C) BFU-E.

Fold Increase in PBPC Levels From Baseline to day 15 After Chemotherapy for Placebo and PEG-rHuMGDF

| . | Placebo + Filgrastim (n = 10) . | PEG-rHuMGDF* + Filgrastim (n = 25) . | P4-151 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GM-CFC | 3 (2-46) | 191 (61-2,358) | .002 |

| Meg-CFC | 5 (2-272) | 247 (36-1,352) | .07 |

| BFU-E | 2 (1-25) | 64 (18-430) | .004 |

| CD34+ cells | 1 (0.7-6) | 20 (4-69) | .03 |

| . | Placebo + Filgrastim (n = 10) . | PEG-rHuMGDF* + Filgrastim (n = 25) . | P4-151 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GM-CFC | 3 (2-46) | 191 (61-2,358) | .002 |

| Meg-CFC | 5 (2-272) | 247 (36-1,352) | .07 |

| BFU-E | 2 (1-25) | 64 (18-430) | .004 |

| CD34+ cells | 1 (0.7-6) | 20 (4-69) | .03 |

PBPC levels are median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: GM-CFC, granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming cells; Meg-CFC, megakaryocyte colony-forming cells; BFU-E, erythroid burst-forming units.

Combined fold increase for all patients administered doses of PEG-rHuMGDF of 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, or 5.0 μg/kg. Doses of PEG-rHuMGDF of 0.03 and 0.1 μg/kg did not enhance mobilization of PBPC compared with placebo plus filgrastim.

P values calculated using the rank sum test.

Safety of PEG-rHuMGDF.PEG-rHuMGDF was very well tolerated and no major adverse events were directly attributable to the cytokine. One patient with lung cancer was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolus on ventilation-perfusion lung scan 12 days after the last of seven doses of PEG-rHuMGDF 1.0 μg/kg. At the time the platelet count was 219 × 109/L. Another patient experienced a self-limiting episode of thrombophlebitis in the right calf, 1 day after ceasing PEG-rHuMGDF 5 μg/kg. At the time the platelet count was 468 × 109/L.

No clinically important alterations were observed in performance status, body weight, vital signs, or coagulation parameters. Bruising and bleeding related to thrombocytopenia were infrequent and mild when they occurred. Table 5 shows the spectrum of nonhematologic adverse effects experienced by patients after the first cycle of chemotherapy. There was no difference in the frequency of these events between placebo and PEG-rHuMGDF cohorts. No patient developed antibodies to PEG-rHuMGDF.

Nonhematologic Adverse Events in 41 Patients Who Received Study Drug

| . | Placebo + Filgrastim (n = 10) . | PEG-rHuMGDF* + Filgrastim (n = 31) . |

|---|---|---|

| Local | ||

| Injection site reaction | 0 (0)5-151 | 2 (6) |

| Systemic | ||

| Lethargy/drowsiness | 1 (10) | 17 (55) |

| Hot flushes/fever5-150 | 6 (60) [1]5-152 | 8 (26) |

| Bone pain | 3 (30) | 8 (26) |

| Neurologic | ||

| Headache | 6 (60) | 13 (42) |

| Dizziness | 3 (30) | 12 (38) |

| Respiratory | ||

| Cough | 1 (10) | 8 (26) |

| Dyspnea | 3 (30) | 12 (38) [3] |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 9 (90) [1] | 22 (71) [4] |

| Diarrhea | 3 (30) | 15 (48) [2] |

| Mucositis | 5 (50) | 8 (26) |

| Metabolic | ||

| Hypokalemia | 2 (20) | 5 (16) |

| Thromboembolic | ||

| Thrombophlebitis | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 1 (3) [1]ρ |

| . | Placebo + Filgrastim (n = 10) . | PEG-rHuMGDF* + Filgrastim (n = 31) . |

|---|---|---|

| Local | ||

| Injection site reaction | 0 (0)5-151 | 2 (6) |

| Systemic | ||

| Lethargy/drowsiness | 1 (10) | 17 (55) |

| Hot flushes/fever5-150 | 6 (60) [1]5-152 | 8 (26) |

| Bone pain | 3 (30) | 8 (26) |

| Neurologic | ||

| Headache | 6 (60) | 13 (42) |

| Dizziness | 3 (30) | 12 (38) |

| Respiratory | ||

| Cough | 1 (10) | 8 (26) |

| Dyspnea | 3 (30) | 12 (38) [3] |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 9 (90) [1] | 22 (71) [4] |

| Diarrhea | 3 (30) | 15 (48) [2] |

| Mucositis | 5 (50) | 8 (26) |

| Metabolic | ||

| Hypokalemia | 2 (20) | 5 (16) |

| Thromboembolic | ||

| Thrombophlebitis | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 1 (3) [1]ρ |

There was no difference in the frequency of any toxicity between patients given placebo and those admininstered PEG-rHuMGDF (Fisher's Exact test).

Not related to neutropenia.

No. of patients (percentage).

Numbers in brackets represent number of events that were grade 3.

ρ This event was grade 4.

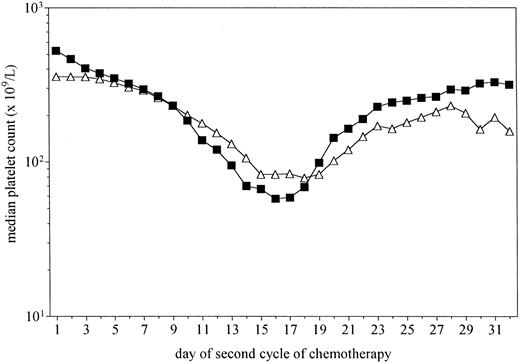

Platelet recovery after cycle 2.Figure 6 shows the median platelet counts after the second cycle of chemotherapy for patients (n = 31) who had received either PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, or 5.0 μg/kg (n = 21) or placebo (n = 10) following the previous cycle. The administration of PEG-rHuMGDF after the previous cycle of chemotherapy had ceased a median of 19 (range, 6 to 27) days before the second cycle of chemotherapy was given. Chemotherapy dose reductions were comparable for the placebo and PEG-rHuMGDF treated groups (P = .69). Platelet counts did not recover to baseline levels in most patients, consistent with the expected cumulative toxicity of the chemotherapy. However, median recovery to a platelet count of at least 150 × 109/L (lower limit of normal range) for those patients who had previously received PEG-rHuMGDF was 21 days compared with 24 days for those who had received placebo (P = .013). The difference in recovery was more pronounced in patients who had a short interval between ceasing PEG-rHuMGDF and administration of chemotherapy, that is, in the patients treated with PEG-rHuMGDF for up to 20 days (median interval, 11 days) compared with those treated for only 7 days (median interval, 19 days). Comparable decreases in the neutrophil count and hematocrit were observed in the PEG-rHuMGDF and placebo groups.

Platelet recovery after the second cycle of chemotherapy for patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg (▪, n = 21) or placebo (▵, n = 10) during the first cycle of chemotherapy, but no study drug in the second cycle. Recovery to platelets of at least 150 × 109/L was more rapid in the PEG-rHuMGDF group (P = .013).

Platelet recovery after the second cycle of chemotherapy for patients administered PEG-rHuMGDF 0.3 to 5.0 μg/kg (▪, n = 21) or placebo (▵, n = 10) during the first cycle of chemotherapy, but no study drug in the second cycle. Recovery to platelets of at least 150 × 109/L was more rapid in the PEG-rHuMGDF group (P = .013).

Tumor response.One patient with small cell lung cancer had a complete response and three patients had a partial response (two with non–small cell lung cancer and one with squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin). All other patients had either stable disease (n = 22) or progression of cancer (n = 15).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the safety and biologic effects of PEG-rHuMGDF when administered concurrently with filgrastim after high-dose carboplatin and cyclophosphamide. We found that PEG-rHuMGDF was well tolerated and accelerated platelet recovery in a dose-dependent manner, but did not influence the depth of the platelet nadir. In addition, delivery of PEG-rHuMGDF before chemotherapy appeared to provide additional enhancement to platelet recovery. This was evident for those patients who received an effective dose of PEG-rHuMGDF up to 2 weeks before the first cycle of chemotherapy, and despite cessation of PEG-rHuMGDF for at least a week before the second cycle. This latter observation must be interpreted with caution because the study was not designed to assess the effects of pretreatment with PEG-rHuMGDF. The mechanism for such a potential effect is unclear, but it may be linked to the stimulatory activity of PEG-rHuMGDF on the early stages of hematopoiesis.30,31 It is conceivable that, as with other haematopoietic regulators,32 prior administration of PEG-rHuMGDF might expand the number of primitive and committed progenitor cells that are then available to generate megakaryocytes after chemotherapy.

The doses of chemotherapy administered in this study were moderately myelosuppressive. The short duration of thrombocytopenia meant that only a few patients required a platelet transfusion. Whether PEG-rHuMGDF can reduce the need for platelet support in situations in which more prolonged and severe thrombocytopenia occurs, such as in the treatment of acute leukemia or salvage therapy for lymphoma, will need to be explored in studies specifically addressing this issue.

There did not appear to be any adverse risk associated with thrombocytosis after treatment with PEG-rHuMGDF. Eleven patients developed a platelet count of over 1,000 × 109/L in the recovery phase after chemotherapy without clinical sequelae. Reduction in the duration of administration of PEG-rHuMGDF in the higher-dose cohorts resulted in lower peak platelet counts after chemotherapy, but did not adversely influence the action of PEG-rHuMGDF on hematopoietic recovery. Two thromboembolic events were diagnosed when the platelet counts were low; moreover, the patient with a pulmonary embolus had ceased PEG-rHuMGDF 12 days earlier. In addition, no consistent changes in platelet function or surface marker expression were observed in these or other patients in the trial. This is consistent with our earlier phase I study, in which platelets produced after administration of up to 1 μg/kg of PEG-rHuMGDF alone were morphologically and functionally normal, and showed no increase in the rate of destruction, as assessed by plasma glycocalicin levels.16,26 PEG-rHuMGDF–induced thrombocytosis therefore appears more akin to a reactive process than to that associated with a myeloproliferative disorder. In vitro abnormalities of platelet aggregation and clinical hemorrhagic and thrombotic events seldom occur in reactive thrombocytosis, but are quite common in patients with essential thrombocythemia.33,34 The low incidence of thrombosis observed is consistent with the rates of venous thromboembolism reported in patients with advanced cancer35 and suggests that the risk of a thromboembolic event related to PEG-rHuMGDF administration, if any, is low.

The addition of PEG-rHuMGDF to filgrastim after chemotherapy resulted in increased circulating levels of progenitor cells on day 15. Although PEG-rHuMGDF mobilized PBPC when administered alone in doses of 0.3 and 1.0 μg/kg,36 (J.E.J.R., unpublished data), the degree of enhancement observed in this study was more pronounced and appeared to be dose related. This effect appears to be of similar or greater magnitude than the synergy between filgrastim and stem cell factor37 or IL-3.38 However, the levels of progenitor cells were lower than expected in the group given placebo and filgrastim. This may have been due to differences in the kinetics of bone marrow release of progenitor cells that were not detected between the two groups because of the infrequent sampling. An additional confounding factor to consider is the observed inter-individual variability in progenitor cell mobilization in response to exogenously administered cytokines.28,39 Nevertheless, these results raise the possibility that the use of PEG-rHuMGDF in combination with filgrastim to mobilize progenitor cells of multiple lineages may provide a more effective method for collecting stem cells for supporting high-dose chemotherapy than filgrastim alone.40

This study shows that PEG-rHuMGDF is an important new agent that enhances platelet recovery after moderately intensive chemotherapy. It can be administered safely with filgrastim and has none of the systemic effects associated with the use of other thrombopoietic cytokines.6-8 It provides hope of an effective and safe means for prevention or treatment of severe thrombocytopenia, which up until now has been managed primarily with transfusions of platelets. Further studies are required to examine the effects of PEG-rHuMGDF on platelet toxicity after more intensive chemotherapy, to investigate the potential clinical benefit of treatment before chemotherapy, and to define more completely its effects on circulating progenitor cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the following people for their support of the study: C. Alt, Dr P. Bardy, J. Bartlett, M. Berndt, J. Boyd, Prof A. Burgess, Dr R. DeBoer, Dr M. Chipman, Dr J.C. Ding, M. Dodds, G. Duggan, Dr S. Fan, J. Hay, W. Hopkins, S. Hurren, Dr K. McGrath, Prof D. Metcalf, Dr P. Mitchell, R. Mansfield, C. O'Malley, L. Phelan, H. Ranouw, A. Ransom, Dr M. Rosenthal, W. Saunders, Dr J. Seymour, Dr J. Szer, R. van Driel, Dr S. Whitehead, ward staff and staff of the Diagnostic Hematology Departments (Austin-Repatriation Medical Centre, Royal Melbourne and Western Hospitals); and Dr J. Marty, R. Mrongovius, J. Renwick, B. Thomson, (Amgen, Australia); D. Barron, T. Paine, K. Rubenstein, Dr W.P. Sheridan, M.L. Trotman, Dr D. Tomita (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA).

Supported in part by grants from the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria, Carlton, Australia; the National Health and Medical Research Council, Canberra; Australia; the Cooperative Research Centre for Cellular Growth Factors, Parkville, Australia; and Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Address reprint requests to Russell L. Basser, MBBS, Director, CDCT, c/o Post Office, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, 3050, Australia.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal