Key Points

HSCT yields satisfactory long-term outcomes in patients with PNP deficiency.

OS was best in early-diagnosed patients without neurologic symptoms.

Visual Abstract

Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) deficiency causes inadequate purine metabolite detoxification, which leads to combined immunodeficiency and variable neurologic symptoms. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) cures the immunodeficiency, but large studies on the long-term outcomes are lacking. In a retrospective study of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, we investigated 46 patients with PNP deficiency from 21 centers. We analyzed the presenting clinical signs and outcomes after HSCT. Cognition (0-3), hearing (0-3), interaction (0-4), movement (0-4), and occupation (0-3) (CHIMO) were scored at the last follow-up (FU) visit (no impairment, 17; mild, 15-16; moderate, 12-14; and severe impairment, <12). The median age at initial presentation was 7.5 (1-48) months. The patients presented with infections (41%), neurological dysfunction (39%), both (15%), or autoimmune disease (5%). At the time of HSCT (median age, 26 [2-192] months), neurological abnormalities were observed in 88% of patients. After a median FU of 7.9 (1.0-22.3) years, 40 patients were alive with a 3-year overall survival (OS)/event-free survival (EFS) probabilities of 86% (confidence interval [CI], 77%-97%)/75% (CI, 64%-89%), respectively. High-level (>50%-100%)/low-level donor chimerism (11%-50%) was observed in 85%/15% of patients, respectively, leading to resolution of T lymphopenia. The median overall CHIMO score was 14 (6-17), while the median scores for each component were 3 (0-3), 3 (1-3), 4 (1-4), 3 (1-4), and 2 (0-3), respectively. Patients who underwent HSCT before 24 months after the initial presentation demonstrated superior OS (P = .049). Neurological symptoms that occurred before 11 months of age were associated with reduced OS (P = .027). While the overall results were satisfactory, earlier diagnosis could further improve outcomes.

Introduction

Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) deficiency is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder of purine metabolism that affects ∼1% to 2% of all patients with combined immunodeficiency (CID).1-8 PNP is an enzyme that reversibly catalyzes the phosphorolysis of inosine, deoxyinosine, guanosine, and deoxyguanosine1-3 Absent or significantly reduced PNP enzyme activity leads to increased levels of deoxyguanosine and deoxyinosine in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine.1,4 The deoxytriphosphate compounds, especially deoxyguanosine triphosphate, accumulate intracellularly and induce apoptosis in lymphocytes and neuronal cells, and T lymphocytes are more susceptible to apoptosis than B lymphocytes.4,5 The diagnosis can be confirmed by determining the purine levels in body fluids using high-performance liquid chromatography.6,7 All individuals with biallelic pathogenic variants in PNP are symptomatic.8

It has been reported that clinical symptoms in PNP deficiency occur at a later stage than in classical severe CID (SCID), particularly between infancy and preschool age.1 Newborn screening for SCID, based on the detection of low numbers or no cells that bear T-cell receptor excision circles, seems to detect only a minority of individuals with PNP deficiency.3,8-15 The more sensitive tandem mass spectrometry analysis of purine metabolites using dried blood spots is unfortunately not routinely available.10,16

Immunodeficiency in PNP deficiency is characterized by the occurrence of recurrent and/or severe bacterial, viral, or fungal infections,17,18 as well other opportunistic infections.11,19,20 In addition, there is a predisposition to autoimmune diseases (AID+), particularly autoimmune cytopenia, and less commonly to macrophage activation syndrome and hematologic malignancies.15,21,22 Up to two-thirds of patients exhibit heterogeneous neurologic symptoms, including developmental delay and neurologic and cognitive deficits.1,23-27 Neurologic involvement varies clinically from normal to severely impaired, even within families with the same molecular defect.17,18,24

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only curative treatment.15,23,24,28,29 Transient metabolic improvement can be achieved with erythrocyte exchange transfusions (ET),30,31 but unlike for adenosine deaminase deficiency, no enzyme replacement therapy is available.32 There are anecdotal reports that neurologic status improves in some patients after HSCT,15,24,28 whereas neurologic damage persists in others;23 thus, the benefit of HSCT on the long-term neurologic outcomes is largely unknown.

In this study, we provide a comprehensive analysis of the onset and nature of clinical presentation and clinical outcomes in a patient cohort of 46 children with PNP deficiency who underwent HSCT.

Patients, materials, and methods

Study design

In this multicenter, retrospective study of the Inborn Errors Working Party (IEWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) (study number 8427029), centers in Europe, Canada, and the United States enrolled patients with proven PNP deficiency who underwent transplantation between 1998 and 2022. The criteria for inclusion required at least 1 of the following: (1) absent or severely deficient PNP enzyme activity (<5% of normal as measured in erythrocytes from untransfused patients) and (2) genetic confirmation of homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations known or predicted to cause PNP deficiency or already detected in a sibling affected with PNP deficiency. Related donors were tested for PNP mutations and PNP activity. Healthy family donors with heterozygous PNP mutations were permitted to donate. Participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent to participate in this study via the EBMT for Europe and Primary Immune Deficiency Treatment Consortium (PIDTC) for Canada and the United States.

Data collection and definitions

Data were collected using specially designed case report forms and included information on the baseline disease-specific characteristics, including infectious, neurologic, and autoimmune symptoms, and laboratory data at clinical presentation and HSCT. The outcome analysis included information on conditioning chemotherapy,33-35 serotherapy, graft source and in vitro manipulation, post-HSCT immunosuppression, primary and secondary graft failure (GF), the need for a second HSCT or cellular therapy (CT; donor lymphocyte infusion [DLI], stem cell boost [SCB] infusion), incidence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and infectious and autoimmune complications (supplemental Material and methods, available on the Blood website).

At the last follow-up visit (FU), data analysis included overall survival (OS; days alive after HSCT), event-free survival (EFS; days alive without a second HSCT or clinical relapse),33 incidence of acute (Glucksberg score) and chronic GVHD (limited, extensive), the percentage of donor chimerism (DC) in the whole blood and/or in sorted myeloid (CD15+neutrophils/CD14+monocytes), T- (CD3+), and B-cell (CD19+) compartments, independence of immunoglobulin G replacement therapy, and, if available, PNP enzyme activity in blood and/or urinary purine metabolite excretion (uric acid, deoxyguanosine triphosphate, guanosine, inosine, deoxyguanosine, and deoxyinosine) according to established local laboratory methods.

At the final FU, the study physicians assessed the neurologic outcomes using a new combination of standardized and validated scores,36-40 including cognition (scoring range, 0-3), hearing (0-3), interaction (0-4), movement (0-4), and occupation (0-3), referred to as the CHIMO score (maximum: 17). Karnofsky and/or Lansky scores were also recorded (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Statistical analysis

Data on the clinical and laboratory characteristics were collected at the time of initial diagnosis, at HSCT, and at the last FU (at least 1 year after HSCT). Categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact test and continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations were calculated using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. For survival, Kaplan-Meier estimates were used for survival and log-rank tests were used for comparison. Data were censored at the date of last FU for surviving patients. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a log-log transformation. Kaplan-Meier curve comparisons between groups were performed using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for univariate analysis of the risk factors associated with EFS and OS. For the Cox proportional hazard regression and depiction, the coxph and ggforest functions were used in R, and to determine the optimal cutoff timepoints in the survival analysis, the surv_cutpoint function in the survminer package in R was applied. A multivariate analysis was not performed because of the small sample size. All analyses were performed using RStudio version 2024.09.0, packages dplyr, forestplot, ggthemes, knitr, survminer, survival, tidyquant, and tidyverse, and Microsoft Excel and Graphpad Prism V9 and 10.

Institutional review board approval was obtained for participation in the study on behalf of the EBMT IEWP.

Results

Patient characteristics

PNP deficiency was diagnosed at a median age of 17.5 months (0-186), including 6 asymptomatic patients (13%) who were diagnosed at birth based on family history. Another patient with a family history of CID was diagnosed at the onset of neurologic symptoms. Allogeneic HSCT was performed at a median age of 25.5 months (2-192). Five of the 6 perinatally diagnosed patients were transplanted before the onset of symptoms. Most patients fulfilled the criteria for leaky T cell-negative, B cell-positive, natural killer cell-positive severe combined immunodeficiency (T-B+NK+SCID) or CID41 (Table 2), and none had reported Omenn syndrome or the presence of maternal lymphocytes. Infectious symptoms without neurologic compromise (I+) were presenting symptoms in 41% (17/41) of patients, neurologic symptoms without signs of immunodeficiency (N+) were the presenting symptoms in 39% (16/41), and combined infectious and neurologic symptoms (I+/N+) were the presenting symptoms in 15% (6/41). AID+ was a presenting symptom in 5% (2/41) of patients, either with or without infectious symptoms. Patients with only 1 type of initial clinical manifestations (I+ or N+ or AID+) presented earlier than patients with a combined occurrence of different types of initial clinical manifestations. The median age at first presentation of I+, N+, AID+, and combined I+/N+ was 5, 8, 13.5, and 15 months, respectively (Table 1). The overall distribution of all N+, I+, and A+ symptoms over time is shown in Figure 1A.

Clinical presentation

| ID . | Sex . | Initial neurologic findings . | Initial I+ and AID+ symptoms . | Type of initial presentation . | I+ present age, mo . | N+ present age, mo . | AID+ present age, mo . | PNP diagnose age, mo . | HSCT at age, mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1∗ | F | Tremor, ataxia, DL | RTI, GI (Giardia) | N | 30 | 6 | 30 | 35 | |

| 2 | F | DL in motor skills | None, VZV (treated with acyclovir) | N | 15 | 6 | 15 | 26 | |

| 3 | M | DL | RTI, OM, diarrhea | I | 1 | 30 | 47 | 51 | |

| 4∗ | F | DL, microcephalus/brachycephalus, encephalitis/meningitis (at 2 y): subsequent hydrocephalus, ataxia, spastic paresis of upper limbs | Diarrhea RTI, OM | I | 4 | 24 | 24 | 35 | |

| 5 | M | DL, generalized hypotonia | Diarrhea, VZV/pneumonia, OM | I | 6 | 9 | 9 | 14 | |

| 6 | F | Ataxia neck/trunk, choreatic movements, polymicrogyria (like sibling not suffering from PNP) | RTI | N | 6 | 3 | 6 | 10 | |

| 7 | M | DL, spastic paresis | Family history (brother had CID) | N | 12 | 12 | 27 | ||

| 8 | F | DL in motor skills, mild truncal hypotonia | Severe VZV | I | 11 | 12 | 12 | 16 | |

| 9 | F | DL | RTI, GI, thrush | I | 5 | 11 | 11 | 14 | |

| 10 | F | DL, spastic paraparesis, MRI: global atrophy, corpus callosum atrophy | RTI, VZV (pneumonia/myocarditis) | N | 23 | 6 | 23 | 25 | |

| 11 | F | Hypotonia, insufficient head control | Severe VZV, septicemia | I | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 | |

| 12 | M | Motoric coordination disorder, spastic paresis | RTI, impetigo, GI (RV) | I | 12 | 24 | 71 | 72 | |

| 13 | F | Ataxia (MRI: normal), after first HSCT ability to walk; deterioration before second HSCT, motoric DL | Thrush, RTI (RSV), GI (RV), AIHA | I | 7 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 24 |

| 14 | M | Lower limb/truncal hypotonia; spastic paresis; motor DL with impaired balance | OM, RTI, severe VZV, zoster | N | 20 | 9 | 9 | 47 | |

| 15 | M | SNHL unrelated to PNP (other cause; a cochlear implant); mild gross motor DL, consanguinity | AIHA, ITP, URT, RTI/bronchiectasis; intussusception | A/I | 23 | None | 23 | 23 | 39 |

| 16 | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 2 | ||

| 17 | F | Generalized hypotonia, DL | RTI, OM; CMV (including CNS) | I/N | 15 | 15 | 15 | 39 | |

| 18 | F | DL of motor and speech function | AIHA, ITP, pyelonephritis; sepsis | I/N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 25 | |

| 19 | M | Spastic paresis, mild spastic dysplasia, DL | AIN, RTI | I/N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 22 |

| 20 | F | Cerebral palsy and spastic paraparesis, DL | RTI, VZV, bronchiectasis, thrush | N | 72 | 8 | 72 | 168 | |

| 21 | M | Ataxia, spastic paraparesis, mild DL | RTI, thrush, dermatitis | I | 1 | 18 | 26 | 28 | |

| 22 | F | Normal | Thrush, GI (Campylobacter) (sibling died from EBV/lymphoma) | I | 24 | None | 24 | 25 | |

| 23 | M | DL, motor retardation with spastic paresis of lower extremities, progressed to spastic tetraparesis | RTI, OM | I/N | 12 | 12 | 12 | 42 | |

| 24 | F | Normal | AIHA, ITP | A | 6 | None | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 25∗ | M | Hemiplegia, gross motor DL; MRI brain: delayed myelination/thin corpus callosum; bilateral lower motor neuron signs in both lower limbs | RTI, paronychia, AIN, CMV/EBV | N | 11 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 31 |

| 26 | F | Upper motor signs at HSCT; motor DL present with asymmetry of tone increased in lower limbs and posturing of upper limbs/head | Family history: sibling had severe neurologic disease and died without HSCT (newborn diagnosis) | N | 5 | 0 | 7 | ||

| 27 | F | DL, atactic, unstable gait, motor DL; after severe VZV; central motor paralysis | AIHA; severe VZV | N | 18 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 36 |

| 28 | M | Normal | Severe VZV | I | 36 | None | 38 | 40 | |

| 29∗ | M | Mild DL, hypotonia | Recurrent thrush | I | 14 | 10 | 21 | 22 | |

| 30 | F | Severe DL with no sitting/crawling/running | RTI, tracheomalacia | N | 12 | 8 | 12 | 20 | |

| 31 | F | Generalized hypotonia Ataxia (noted after general anesthesia). Unsafe swallow | RTI (influenza A). GI (NV, SP, RV) | I | 4 | 16 | 4 | 18 | |

| 32 | M | Choreoathetosis, motor DL | VZV (at 48 mo of age), DLBCL (EBV-related at 186 mo of age) | N | 48 | 20 | 186 | 192 | |

| 33 | M | Ataxia | Thrush | I | 12 | 14 | 18 | 43 | |

| 34 | M | Stiffness both lower extremities and ankles; mild, nonprogressive gait difficulty | Atopic dermatitis asthma; sinusitis, vaccine related VZV (via sibling) | N | 48 | 12 | 108 | 119 | |

| 35 | M | Motor DL, ataxia, spastic diplegia; MRI: normal | Asthma, cow's milk/peanut allergy, vaccine related VZV, RTI | N | 18 | 18 | 84 | 92 | |

| 36∗ | M | Hypotonia, motor and speech delay | OM, thrush, zoster (VZV); CMV/ADV | N | 48 | 9 | 48 | 52 | |

| 37 | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 2 | ||

| 38‡ | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 4 | ||

| 39‡ | M | Grossly normal examination; ataxia, hemi spastic paresis; motor delay | RTI, AIHA, dermatitis, zoster (VZV) | I | 1 | 11 | 11 | 35 | 41 |

| 40‡ | M | Motor DL, axial hypotonia | Family history (patient 39); cleft palate; OM with conductive hearing loss | I/N | 12 | 12 | 17 | 26 | |

| 41‡ | M | Normal | Family history (sibling of patient 39/40) (antenatal diagnosis)† | None | None | 0 | 4 | ||

| 42 | M | Generalized hypotonia | RTI (ADV/CV) diarrhea, thrush | I | 5 | 7 | 11 | 12 | |

| 43 | F | Motor DL, generalized hypotonia | Aphthous stomatitis, EBV-LGN (CNS, kidney, spleen, liver) | I | 3 | 17 | 17 | 22 | |

| 44∗ | F | Spastic diplegia, DL | MAS and arthritis | N | 5 | 31 | 33 | 37 | |

| 45 | F | Motor DL, spastic tendency, ataxia, hypotonia | Vaccine related VZV | I/N | 21 | 6 | 21 | 23 | |

| 46 | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 3 |

| ID . | Sex . | Initial neurologic findings . | Initial I+ and AID+ symptoms . | Type of initial presentation . | I+ present age, mo . | N+ present age, mo . | AID+ present age, mo . | PNP diagnose age, mo . | HSCT at age, mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1∗ | F | Tremor, ataxia, DL | RTI, GI (Giardia) | N | 30 | 6 | 30 | 35 | |

| 2 | F | DL in motor skills | None, VZV (treated with acyclovir) | N | 15 | 6 | 15 | 26 | |

| 3 | M | DL | RTI, OM, diarrhea | I | 1 | 30 | 47 | 51 | |

| 4∗ | F | DL, microcephalus/brachycephalus, encephalitis/meningitis (at 2 y): subsequent hydrocephalus, ataxia, spastic paresis of upper limbs | Diarrhea RTI, OM | I | 4 | 24 | 24 | 35 | |

| 5 | M | DL, generalized hypotonia | Diarrhea, VZV/pneumonia, OM | I | 6 | 9 | 9 | 14 | |

| 6 | F | Ataxia neck/trunk, choreatic movements, polymicrogyria (like sibling not suffering from PNP) | RTI | N | 6 | 3 | 6 | 10 | |

| 7 | M | DL, spastic paresis | Family history (brother had CID) | N | 12 | 12 | 27 | ||

| 8 | F | DL in motor skills, mild truncal hypotonia | Severe VZV | I | 11 | 12 | 12 | 16 | |

| 9 | F | DL | RTI, GI, thrush | I | 5 | 11 | 11 | 14 | |

| 10 | F | DL, spastic paraparesis, MRI: global atrophy, corpus callosum atrophy | RTI, VZV (pneumonia/myocarditis) | N | 23 | 6 | 23 | 25 | |

| 11 | F | Hypotonia, insufficient head control | Severe VZV, septicemia | I | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 | |

| 12 | M | Motoric coordination disorder, spastic paresis | RTI, impetigo, GI (RV) | I | 12 | 24 | 71 | 72 | |

| 13 | F | Ataxia (MRI: normal), after first HSCT ability to walk; deterioration before second HSCT, motoric DL | Thrush, RTI (RSV), GI (RV), AIHA | I | 7 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 24 |

| 14 | M | Lower limb/truncal hypotonia; spastic paresis; motor DL with impaired balance | OM, RTI, severe VZV, zoster | N | 20 | 9 | 9 | 47 | |

| 15 | M | SNHL unrelated to PNP (other cause; a cochlear implant); mild gross motor DL, consanguinity | AIHA, ITP, URT, RTI/bronchiectasis; intussusception | A/I | 23 | None | 23 | 23 | 39 |

| 16 | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 2 | ||

| 17 | F | Generalized hypotonia, DL | RTI, OM; CMV (including CNS) | I/N | 15 | 15 | 15 | 39 | |

| 18 | F | DL of motor and speech function | AIHA, ITP, pyelonephritis; sepsis | I/N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 25 | |

| 19 | M | Spastic paresis, mild spastic dysplasia, DL | AIN, RTI | I/N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 22 |

| 20 | F | Cerebral palsy and spastic paraparesis, DL | RTI, VZV, bronchiectasis, thrush | N | 72 | 8 | 72 | 168 | |

| 21 | M | Ataxia, spastic paraparesis, mild DL | RTI, thrush, dermatitis | I | 1 | 18 | 26 | 28 | |

| 22 | F | Normal | Thrush, GI (Campylobacter) (sibling died from EBV/lymphoma) | I | 24 | None | 24 | 25 | |

| 23 | M | DL, motor retardation with spastic paresis of lower extremities, progressed to spastic tetraparesis | RTI, OM | I/N | 12 | 12 | 12 | 42 | |

| 24 | F | Normal | AIHA, ITP | A | 6 | None | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 25∗ | M | Hemiplegia, gross motor DL; MRI brain: delayed myelination/thin corpus callosum; bilateral lower motor neuron signs in both lower limbs | RTI, paronychia, AIN, CMV/EBV | N | 11 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 31 |

| 26 | F | Upper motor signs at HSCT; motor DL present with asymmetry of tone increased in lower limbs and posturing of upper limbs/head | Family history: sibling had severe neurologic disease and died without HSCT (newborn diagnosis) | N | 5 | 0 | 7 | ||

| 27 | F | DL, atactic, unstable gait, motor DL; after severe VZV; central motor paralysis | AIHA; severe VZV | N | 18 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 36 |

| 28 | M | Normal | Severe VZV | I | 36 | None | 38 | 40 | |

| 29∗ | M | Mild DL, hypotonia | Recurrent thrush | I | 14 | 10 | 21 | 22 | |

| 30 | F | Severe DL with no sitting/crawling/running | RTI, tracheomalacia | N | 12 | 8 | 12 | 20 | |

| 31 | F | Generalized hypotonia Ataxia (noted after general anesthesia). Unsafe swallow | RTI (influenza A). GI (NV, SP, RV) | I | 4 | 16 | 4 | 18 | |

| 32 | M | Choreoathetosis, motor DL | VZV (at 48 mo of age), DLBCL (EBV-related at 186 mo of age) | N | 48 | 20 | 186 | 192 | |

| 33 | M | Ataxia | Thrush | I | 12 | 14 | 18 | 43 | |

| 34 | M | Stiffness both lower extremities and ankles; mild, nonprogressive gait difficulty | Atopic dermatitis asthma; sinusitis, vaccine related VZV (via sibling) | N | 48 | 12 | 108 | 119 | |

| 35 | M | Motor DL, ataxia, spastic diplegia; MRI: normal | Asthma, cow's milk/peanut allergy, vaccine related VZV, RTI | N | 18 | 18 | 84 | 92 | |

| 36∗ | M | Hypotonia, motor and speech delay | OM, thrush, zoster (VZV); CMV/ADV | N | 48 | 9 | 48 | 52 | |

| 37 | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 2 | ||

| 38‡ | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 4 | ||

| 39‡ | M | Grossly normal examination; ataxia, hemi spastic paresis; motor delay | RTI, AIHA, dermatitis, zoster (VZV) | I | 1 | 11 | 11 | 35 | 41 |

| 40‡ | M | Motor DL, axial hypotonia | Family history (patient 39); cleft palate; OM with conductive hearing loss | I/N | 12 | 12 | 17 | 26 | |

| 41‡ | M | Normal | Family history (sibling of patient 39/40) (antenatal diagnosis)† | None | None | 0 | 4 | ||

| 42 | M | Generalized hypotonia | RTI (ADV/CV) diarrhea, thrush | I | 5 | 7 | 11 | 12 | |

| 43 | F | Motor DL, generalized hypotonia | Aphthous stomatitis, EBV-LGN (CNS, kidney, spleen, liver) | I | 3 | 17 | 17 | 22 | |

| 44∗ | F | Spastic diplegia, DL | MAS and arthritis | N | 5 | 31 | 33 | 37 | |

| 45 | F | Motor DL, spastic tendency, ataxia, hypotonia | Vaccine related VZV | I/N | 21 | 6 | 21 | 23 | |

| 46 | F | Normal | Family history† (newborn diagnosis) | None | None | 0 | 3 |

ADV, adenovirus; CV, coronavirus; DL, developmental delay; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; LGN, lymphoid granulomatosis; GI, gastrointestinal infection; I+, immunodeficiency; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; N+, neurologic abnormalities; OM, otitis media; NV, norovirus; RV, rotavirus; RTI, respiratory tract infection; SP, sapovirus; URT, urinary tract infection.

Deceased patient.

Erythrocyte exchange transfusion after birth.

Siblings of 1 family.

Age and clinical manifestations of the cohort. (A) Distribution of the age at first symptom onset (x-axis) across different initial clinical manifestations (y-axis: neurologic, infectious, or autoimmune). (B) Percentage of patients who presented with various clinical features over the whole period of study until HSCT. MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; M.Still-like, Morbus Still-like.

Age and clinical manifestations of the cohort. (A) Distribution of the age at first symptom onset (x-axis) across different initial clinical manifestations (y-axis: neurologic, infectious, or autoimmune). (B) Percentage of patients who presented with various clinical features over the whole period of study until HSCT. MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; M.Still-like, Morbus Still-like.

All 46 patients (20 male, 26 female) had low (<5%) or no PNP enzyme activity in erythrocytes and/or genetic mutations compatible with the diagnosis of severe PNP deficiency. Four patients who were diagnosed at birth underwent ET.30 A total of 23 patients (50%) had available PNP genotyping, which revealed compound heterozygous (n = 10) and homozygous (n = 13) variants with exon 2 and c.172C>T p.(Arg58∗) being the most common variant (n = 2 homozygous and n = 4 heterozygous),15,42 followed by a homozygous intronic variant c.286-18G>A in 5 patients15,43 (Table 2).

Immunologic phenotype, pretransplantation erythrocyte PNP enzyme activity, and mutations of the PNP gene

| Patient ID . | CD3 T (per μL) . | CD4/45RA T (per μL) . | B (per μL) . | NK (per μL) . | ANC (per μL) . | Eos (per μL) . | IgG (g/L) . | IgA (g/L) . | IgA (g/L) . | IgM (g/L) . | Erythrocyte PNP activity∗ . | Mutation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1† | 7 | N.a. | 33 | 1850 | 56 | 11 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.82 | Undetectable | ||

| 2 | 96 | N.a. | 61 | 233 | 4730 | 0 | 7.8 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 2.23 | Undetectable | |

| 3 | 65 | N.a. | 24 | 250 | 1100 | 100 | 18.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.15 | Undetectable | |

| 4† | 336 | N.a. | 25 | 274 | 350 | 775 | 9.9 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 1.99 | Undetectable | |

| 5 | 230 | N.a. | 32 | 750 | 3420 | 340 | 8.3 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.58 | Undetectable | |

| 6 | 48 | N.a. | 30 | 43 | 3600 | 90 | 8.5 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 1.53 | Undetectable | |

| 7 | 37 | 48 | 14 | 132 | 300 | 0 | 5.5 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.14 | Undetectable | Homozygous intronic variant c286-18G>A |

| 8 | 65 | 65 | 88 | 216 | 4800 | 100 | 9.8 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.08 | Undetectable | Homozygous intronic variant c286-18G>A |

| 9 | 444 | 444 | 48 | 60 | 6700 | 200 | 10.4 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.18 | Undetectable | Nonsense c.172C>T (R58X) |

| 10 | 28 | N.a. | 40 | 220 | 810 | 90 | 7.1 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 1.15 | Undetectable | |

| 11 | 1131 | N.a. | 48 | 320 | 7128 | 648 | 1.88 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.5 | Reduced | |

| 12 | 1160 | N.a. | 420 | 139 | 4510 | 896 | 786 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.85 | Undetectable | |

| 13 | 13 | N.a. | 57 | 110 | 3200 | 150 | 24.5‡ | <0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | Undetectable | |

| 14 | 92 | 5 | 67 | 260 | 940 | 40 | 13.3§ | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1.36 | Reduced | |

| 15 | 20 | 4 | 30 | 40 | 700 | 70 | 9.33 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.4 | Undetectable | |

| 16ǁ | 658 | N.a. | 102 | 212 | 64 | 0.3 | N.a. | 0.07 | 0.23 | Undetectable | ||

| 17 | 12 | N.a. | 9 | 52 | 3100 | 200 | <0.3 | 0.04 | 0.04 | <0.05 | Reduced | Homozygous c.383A>G |

| 18 | 348 | N.a. | 76 | 242 | 250 | 650 | 16.4 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1,8 | Undetectable | |

| 19 | 120 | 50 | 60 | 150 | 0 | 780 | 6.7 | 0.07 | 0.07 | n/a | Undetectable | |

| 20 | 207 | N.a. | 100 | 205 | 5170 | 110 | 7.13 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.83 | Reduced | Homozygous missense c.117A>T |

| 21 | 145 | N.a. | 29 | 189 | 3700 | 400 | 3.42 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.42 | Undetectable | |

| 22 | 59 | N.a. | 25 | 330 | 1190 | 275 | 3.4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | Undetectable | |

| 23 | 99 | 6 | 26 | 39 | 2542 | 101 | 7.88 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 1.12 | Reduced | Compound-heterozygous Exon 2 c.58CGA>TGA Exon 3 c.98GAA>TAA |

| 24 | 172 | 38/0 | 37 | 159 | 2120 | 180 | 8.58 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 2.08 | Reduced | Compound heterozygous Exon2 c.172C>T p.Arg58Stop Exon 4 c.389T>C p.Met130Thr |

| 25† | 130 | 3 | 150 | 170 | 1190 | 410 | 13.3 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1.36 | Undetectable | |

| 26ǁ | 50 | 9 | 30 | 5180 | 370 | n.d. | 0.08 | 0.09 | Reduced | |||

| 27 | 70 | N.a. | 50 | 190 | 3687 | 209 | 12.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.7 | Undetectable | |

| 28 | 117 | N.a. | 75 | 158 | 2003 | 940 | 5.9 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.75 | Reduced | |

| 29† | 80 | 47 | 53 | 118 | 484 | 66 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 | Undetectable | Compound heterozygous Exon 2 Arg24Termc. 70 C>T Exon 3 Glu89. Lys c.265G>A |

| 30 | 43 | N.a. | 24 | 156 | 5200 | 190 | 10 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | Undetectable | |

| 31 | 10 | 0 | 100 | 70 | 760 | 120 | 7.94 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.41 | Reduced | Homozygous c.383A>G, p.D128G |

| 32 | 250 | 10 | 57 | 157 | 11.5 | 0.71 | 0.38 | Undetectable | c.487T>C, p.Ser163Pro | |||

| 33 | 369 | 35 | 101 | 93 | 2700 | 7 | 1.67 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.18 | Undetectable | |

| 34 | 19 | 0 | 15 | 26 | 6300 | 0.2 | 8.99 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 41 | Reduced | Compound heterozygous c.234R>P; c.212L>P |

| 35 | 170 | 15 | 161 | 55 | 6400 | 0.1 | 8.29 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 63 | Not done | Compound heterozygous c.234R>P; c.212L>P |

| 36† | 158 | 2 | 72 | 531 | 4000 | 0.14 | 11.8 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 133 | Undetectable | Compound heterozygous |

| 37ǁ | 1299 | 185 | 143 | 5150 | 176 | 11.85¶ | N.a. | 0.04 | 0.03 | Reduced | Homozygous c.286-18G>A | |

| 38ǁ | 511 | 239 | 23 | 9460 | 120 | 11.2¶ | N.a. | 0.04 | 0.05 | Reduced | Homozygous c.286-18G>A | |

| 39 | 60 | 9 | 40 | 80 | 1400 | 200 | 8.82 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.85 | Undetectable | c.172C>T, p(ARG58∗); c.701G>C, p.(Arg234Pro) |

| 40 | 90 | 14 | 120 | N.a. | 3000 | 1600 | 10.35 | N.a. | 0.42 | 1.29 | Undetectable | c.172C>T, p(ARG58∗); c.701G>C, p.(Arg234Pro) |

| 41ǁ | 2510 | 1711 | 320 | N.a. | 6200 | 400 | 2.05 | N.a. | 0.06 | 0.7 | Undetectable | c.172C>T, p(ARG58∗); c.701G>C, p.(Arg234Pro) |

| 42 | 34 | 22/0 | 165 | 290 | 3710 | 180 | 10.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.07 | Undetectable | Homozygous c.59A>C(p.H20P)(p.His20Pro) |

| 43 | 36 | N.a. | 88 | 372 | 1420 | 510 | 2.35 | <0.22 | <0.22 | 0.37 | ND | Homozygous c.172C>T |

| 44† | 38 | N.a. | 3 | 59 | 22 400 | 0 | 9.56 | 0.43 | 0.33 | Undetectable | Homozygous c.286-2A>T | |

| 45 | 170 | 19 | 30 | 160 | 5.49 | 0.04 | 1.1 | <0,1 | <0,1 | 1.28 | Reduced | Homozygous c.265G>A, p.Glu89Lys |

| 46ǁ | 830 | 103 | 50 | 260 | 3.43 | 0.06 | 5.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.33 | Undetectable | Homozygous c.244C>T, p.GLN82∗ |

| Patient ID . | CD3 T (per μL) . | CD4/45RA T (per μL) . | B (per μL) . | NK (per μL) . | ANC (per μL) . | Eos (per μL) . | IgG (g/L) . | IgA (g/L) . | IgA (g/L) . | IgM (g/L) . | Erythrocyte PNP activity∗ . | Mutation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1† | 7 | N.a. | 33 | 1850 | 56 | 11 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.82 | Undetectable | ||

| 2 | 96 | N.a. | 61 | 233 | 4730 | 0 | 7.8 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 2.23 | Undetectable | |

| 3 | 65 | N.a. | 24 | 250 | 1100 | 100 | 18.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.15 | Undetectable | |

| 4† | 336 | N.a. | 25 | 274 | 350 | 775 | 9.9 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 1.99 | Undetectable | |

| 5 | 230 | N.a. | 32 | 750 | 3420 | 340 | 8.3 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.58 | Undetectable | |

| 6 | 48 | N.a. | 30 | 43 | 3600 | 90 | 8.5 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 1.53 | Undetectable | |

| 7 | 37 | 48 | 14 | 132 | 300 | 0 | 5.5 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.14 | Undetectable | Homozygous intronic variant c286-18G>A |

| 8 | 65 | 65 | 88 | 216 | 4800 | 100 | 9.8 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.08 | Undetectable | Homozygous intronic variant c286-18G>A |

| 9 | 444 | 444 | 48 | 60 | 6700 | 200 | 10.4 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.18 | Undetectable | Nonsense c.172C>T (R58X) |

| 10 | 28 | N.a. | 40 | 220 | 810 | 90 | 7.1 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 1.15 | Undetectable | |

| 11 | 1131 | N.a. | 48 | 320 | 7128 | 648 | 1.88 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.5 | Reduced | |

| 12 | 1160 | N.a. | 420 | 139 | 4510 | 896 | 786 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.85 | Undetectable | |

| 13 | 13 | N.a. | 57 | 110 | 3200 | 150 | 24.5‡ | <0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | Undetectable | |

| 14 | 92 | 5 | 67 | 260 | 940 | 40 | 13.3§ | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1.36 | Reduced | |

| 15 | 20 | 4 | 30 | 40 | 700 | 70 | 9.33 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.4 | Undetectable | |

| 16ǁ | 658 | N.a. | 102 | 212 | 64 | 0.3 | N.a. | 0.07 | 0.23 | Undetectable | ||

| 17 | 12 | N.a. | 9 | 52 | 3100 | 200 | <0.3 | 0.04 | 0.04 | <0.05 | Reduced | Homozygous c.383A>G |

| 18 | 348 | N.a. | 76 | 242 | 250 | 650 | 16.4 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1,8 | Undetectable | |

| 19 | 120 | 50 | 60 | 150 | 0 | 780 | 6.7 | 0.07 | 0.07 | n/a | Undetectable | |

| 20 | 207 | N.a. | 100 | 205 | 5170 | 110 | 7.13 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.83 | Reduced | Homozygous missense c.117A>T |

| 21 | 145 | N.a. | 29 | 189 | 3700 | 400 | 3.42 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.42 | Undetectable | |

| 22 | 59 | N.a. | 25 | 330 | 1190 | 275 | 3.4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | Undetectable | |

| 23 | 99 | 6 | 26 | 39 | 2542 | 101 | 7.88 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 1.12 | Reduced | Compound-heterozygous Exon 2 c.58CGA>TGA Exon 3 c.98GAA>TAA |

| 24 | 172 | 38/0 | 37 | 159 | 2120 | 180 | 8.58 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 2.08 | Reduced | Compound heterozygous Exon2 c.172C>T p.Arg58Stop Exon 4 c.389T>C p.Met130Thr |

| 25† | 130 | 3 | 150 | 170 | 1190 | 410 | 13.3 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1.36 | Undetectable | |

| 26ǁ | 50 | 9 | 30 | 5180 | 370 | n.d. | 0.08 | 0.09 | Reduced | |||

| 27 | 70 | N.a. | 50 | 190 | 3687 | 209 | 12.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.7 | Undetectable | |

| 28 | 117 | N.a. | 75 | 158 | 2003 | 940 | 5.9 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.75 | Reduced | |

| 29† | 80 | 47 | 53 | 118 | 484 | 66 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 | Undetectable | Compound heterozygous Exon 2 Arg24Termc. 70 C>T Exon 3 Glu89. Lys c.265G>A |

| 30 | 43 | N.a. | 24 | 156 | 5200 | 190 | 10 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | Undetectable | |

| 31 | 10 | 0 | 100 | 70 | 760 | 120 | 7.94 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.41 | Reduced | Homozygous c.383A>G, p.D128G |

| 32 | 250 | 10 | 57 | 157 | 11.5 | 0.71 | 0.38 | Undetectable | c.487T>C, p.Ser163Pro | |||

| 33 | 369 | 35 | 101 | 93 | 2700 | 7 | 1.67 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.18 | Undetectable | |

| 34 | 19 | 0 | 15 | 26 | 6300 | 0.2 | 8.99 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 41 | Reduced | Compound heterozygous c.234R>P; c.212L>P |

| 35 | 170 | 15 | 161 | 55 | 6400 | 0.1 | 8.29 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 63 | Not done | Compound heterozygous c.234R>P; c.212L>P |

| 36† | 158 | 2 | 72 | 531 | 4000 | 0.14 | 11.8 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 133 | Undetectable | Compound heterozygous |

| 37ǁ | 1299 | 185 | 143 | 5150 | 176 | 11.85¶ | N.a. | 0.04 | 0.03 | Reduced | Homozygous c.286-18G>A | |

| 38ǁ | 511 | 239 | 23 | 9460 | 120 | 11.2¶ | N.a. | 0.04 | 0.05 | Reduced | Homozygous c.286-18G>A | |

| 39 | 60 | 9 | 40 | 80 | 1400 | 200 | 8.82 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.85 | Undetectable | c.172C>T, p(ARG58∗); c.701G>C, p.(Arg234Pro) |

| 40 | 90 | 14 | 120 | N.a. | 3000 | 1600 | 10.35 | N.a. | 0.42 | 1.29 | Undetectable | c.172C>T, p(ARG58∗); c.701G>C, p.(Arg234Pro) |

| 41ǁ | 2510 | 1711 | 320 | N.a. | 6200 | 400 | 2.05 | N.a. | 0.06 | 0.7 | Undetectable | c.172C>T, p(ARG58∗); c.701G>C, p.(Arg234Pro) |

| 42 | 34 | 22/0 | 165 | 290 | 3710 | 180 | 10.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.07 | Undetectable | Homozygous c.59A>C(p.H20P)(p.His20Pro) |

| 43 | 36 | N.a. | 88 | 372 | 1420 | 510 | 2.35 | <0.22 | <0.22 | 0.37 | ND | Homozygous c.172C>T |

| 44† | 38 | N.a. | 3 | 59 | 22 400 | 0 | 9.56 | 0.43 | 0.33 | Undetectable | Homozygous c.286-2A>T | |

| 45 | 170 | 19 | 30 | 160 | 5.49 | 0.04 | 1.1 | <0,1 | <0,1 | 1.28 | Reduced | Homozygous c.265G>A, p.Glu89Lys |

| 46ǁ | 830 | 103 | 50 | 260 | 3.43 | 0.06 | 5.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.33 | Undetectable | Homozygous c.244C>T, p.GLN82∗ |

Immunologic parameters at diagnosis.

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Eos, eosinophils; ID, identifier; Ig, immunoglobulin; N.a., not available; NK, natural killer cells.

Untransfused patients (according to local laboratory normal ranges and SI units).

Deceased patient.

Monoclonal IgG kappa.

On intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Neonatal diagnosis owing to family history (patients 37, 38, 41, and 46 with erythrocyte exchange transfusions after birth).

Maternal IgG.

In patients with symptoms, primary immunodeficiency mainly manifested as recurrent bacterial respiratory tract infections (33/41; 80%) and viral infections (22/41; 54%), mainly by varicella zoster virus (VZV) (15/41; 37%), which caused encephalitis, myocarditis, pneumonitis, shingles (12/41; 29%), or postvaccination manifestations (3/41; 7%). Symptomatic infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV; 3/41; 7%), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV; 2/41; 5%), and herpes simplex virus (HSV; 1/41; 2.4%) were less common. Fungal infections at presentation consisted primarily of mucosal Candida-induced thrush (9/41; 22%).

Neurologic manifestations before HSCT were primarily developmental delay (33/41; 80%), followed by spastic paresis (n = 17; 41%), muscular hypotonia (n = 14; 34%), ataxia (n = 11; 27%), tremor/chorea (n = 2; 5%), and speech delay (n = 3; 7%). Other neurologic findings included polymicrogyria (patient 6), and sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) (patient 15). Siblings of the latter patients had polymicrogyria or SNHL without evidence of a PNP deficiency.

The rate of patients with neurologic symptoms/developmental delay increased to 88% (36/41) overall at the time of HSCT, including 6 patients with central nervous system (CNS) infections and severe systemic viral infections caused by VZV and CMV (patients 4, 14, 17, 20, 27, and 28) and, in addition, 1 patient with EBV-lymphoid granulomatosis (patient 43)

Before HSCT, 19.5% (8/41) of patients developed AID, including Evans syndrome (autoimmune hemolytic anemia [AIHA]/immune thrombocytopenia [ITP]) in 7% (3/41), AIHA in 7% (3/41), AIN in 5% (2/41), and macrophage activation syndrome with polyarthritis in 2.5% (1/41).

Transplantation procedures, GF, and CTs

A total of 46 patients received a primary HSCT after conditioning with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC; 15/46; 33%) and myeloablative conditioning (MAC; 29/46; 63%) or with no conditioning (2/46; 4%). Donors included human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched family (13/46; including 1 umbilical cord blood [UCB]), haploidentical family (8/46), matched unrelated (18/46; 15/46 HLA-10/10, 3/46 HLA-9/10) and unrelated UCB donors (7/46; 3/46 HLA 6/6, 3/46 5/6 and 1/46 4/6 match).

The graft sources included bone marrow (22/46; 48%), peripheral blood stem cells (16/46; 35%), and UCB (8/46; 17%). For GVHD and rejection prophylaxis, 67% (31/46) patients received in vivo T-cell depletion with antithymocyte globulin (ATG), including rabbit ATG (7/46; 15%), rabbit anti–T-lymphocyte globulin (4/46; 9%), horse ATG (1/46; 2%), and with alemtuzumab (19/46; 41%) or posttransplant cyclophosphamide (2/46; 4%). No serotherapy was given in 35% (16/46) of patients. In vitro graft manipulations, including T-cell receptor (TCR) α-β/CD19 depletion (2/46) and CD34 selection (1/46), were performed in 7% (3/46) of patients.

CTs included 5 hematopoietic SCBs (4/5, without T-cell depletion; 1/5 with CD34 selection), 3 mesenchymal stem cell infusions, and 4 DLIs (1/4 with CD45RA depletion), which were administered between 47 and 240 days after the first HSCT (Table 3).

HSCT characteristics and complications

| ID . | Age at HSCT (mo) . | Donor . | HLA . | Graft . | T-cell depletion∗ . | Conditioning† . | Serotherapy . | GVHD prophylaxis . | Acute GVHD . | Chronic GVHD . | Post-HSCT CT . | Outcome (mo/d after HSCT) . | Complications >HSCT . | AID >HSCT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‡ | 35 | MMFD | 3/6 | BM | Yes | Bu 16 Cy 200 TT 20 (MAC) | None | None | 2 | NA | Died (d+49) | ADV | ||

| 2 | 26 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 20 Flu 200 (MAC) | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+156) | |||

| 3 | 51 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 16 Flu 120 (MAC) | None | CSA | 3 | Yes | Alive (mo+125) | |||

| 4‡ | 35 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 19.2 Flu 160 Cy 120 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | 2 | Yes | Died (mo+33) | Sepsis/meningitis (chronic extensive GVHD) | ||

| 5 | 14 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 19.2 Flu 160 Cy 120 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+84) | |||

| 6 | 10 | MMFD | 3/6 | PBSC | Yes | Bu 16 Flu 160 TT 10 (MAC) | None | None | No | No | Alive (mo+70) | |||

| 7 | 27 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | None | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+221) | Disseminated BCG Psoas abscess | AIHA | |

| 8 | 16 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 20 Cy 200 (MAC) | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+151) | |||

| 9 | 14 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 16 Flu 160 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+114) | |||

| 10 | 25 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-G 20 | CSA | 1 | Yes | Alive (mo+161) | |||

| 11 | 6 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-G 20 | CSA | 3 | Yes | DLI (d+73) | Alive (mo+98) | RTI Klebsiella, pancytopenia | |

| 12 | 72 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Bu 12.8 Cy 120 (MAC) | ATG-G 40 | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+126) | |||

| 13 | 20 | MMFD | 4/6 | PBSC | Yes CD34+pos | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-T 20 | None | 1 | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+14) | Alive (mo+260) | AIHA§ ITP§ | |

| 14 | 47 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MTX | 1 | No | Alive (mo+192) | VZV (zoster) | ||

| 15 | 39 | MFD | 6/6 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MMF | 3 | No | Alive (mo+137) | Pneumatosis intestinalis | ||

| 16 | 2 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | 2 | No | SCB (mo+9) | Alive (mo+240) | VOD, pneumonitis, nephritis | AIHA§ Alopecia totalis§ |

| 17 | 39 | MFD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/ MMF | 3 | No | Alive (mo+65) | |||

| 18 | 25 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 16 Flu 160 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX/ rituximab | No | No | Alive (mo+87) | VOD, pneumonitis | ||

| 19 | 22 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA | No | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+41) | Alive (mo+62) | ||

| 20 | 168 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-T 10 | CSA/ MMF | No | No | Alive (mo+28) | |||

| 21 | 28 | UCB | 5/6 | UCB | No | Treo 42 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 0.3 | CSA/ MMF | No | Yes | Alive (mo+20) | |||

| 22 | 25 | MFD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | None | CSA/ MTX | 2 | Yes | Alive (mo+125) | |||

| 23 | 42 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Treo 42 Flu 160 TT 8 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+22) | |||

| 24 | 12 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Treo 42 Flu 160 (RIC) | ATG-G 45 | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+94) | |||

| 25‡ | 31 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MMF | 4 | NA | SCB | Died (mo+8) | Acute relapsing GVHD (gut) | |

| 26 | 7 | MUD | 9/10 | PBSC | Yes CD34+pos | Treo 36 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MMF | 1 | No | Alive (mo+72) | |||

| 27 | 36 | MFD | 6/6 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Flu 150 (MAC) | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+156) | VZV (zoster) | ||

| 28 | 40 | UCB | 6/6 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | None | CSA/Pred | No | No | Alive (mo+96) | |||

| 29‡ | 22 | UCB | 10/10 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Flu 140 Mel 70 (MAC) | ATG-T 10 | CSA/Pred | No | NA | Died (d+20) | Neurologic decline | ||

| 30 | 20 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 80 Flu 150 (MAC) | ATG-T 10 | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+108) | RTI (ADV, PIV3, metapneumovirus) | ||

| 31 | 18 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Mel 140 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MMF | 1 | Yes | Alive (mo+24) | |||

| 32 | 192 | MMFD | 3/6 | PBSC | Yes TCRab/CD19 | Treo 42 Flu 150 TT 10 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.3 | None | 2 | No | Alive (mo+28) | GI (ADV, NV) RTI (Covid-19) | ||

| 33 | 43 | UCB | 5/6 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | ATG-E 90 | CSA/pred | No | Yes | Alive (mo+156) | AIHA§ ITP§ DM Graves disease | ||

| 34 | 119 | UCB | 4/6 | UCB | No | Flu 125 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 2.3 | Tacro MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+96) | |||

| 35 | 92 | UCB | 6/6 | UCB | No | Flu 125 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 2.4 | Tacro/MTX | 2nd HSCT (mo+5) | Autologous recovery | VZV (zoster) RTI by EBV | |||

| 36‡ | 52 | UCB | 5/6 | UCB | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 TT 7 (MAC) | Alemt. 3.2 | Tacro/MTX | 3 | NA | Died (mo+8.5) | ADV, CMV (acute relapsing GVHD) | ||

| 37 | 2 | MMFD | 7/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 55 Cy 20 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 0.4 | PtCY d+3/+4 Tacro/MMF | No | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+17) | Alive (mo+80) | EBV (rituximab) RTI (Aspergillus) | AIHA |

| 38 | 4 | MUD | 9/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 79 Flu 160 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MMF | 3 | No | Alive (mo+53) | VOD | ||

| 39 | 41 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Bu 12 Flu 250 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+30) | EBV+PTLD (rituximab) GI (sapovirus) Neisseria bacteremia | ||

| 40 | 26 | MUD | 9/10 | PBSC | No | Bu 12 Flu 250 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | 2 | No | Alive (mo+22) | EBV (rituximab) RTI (rhinovirus/enterovirus/CV) GI (sapovirus) | ||

| 41 | 4 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Bu12 Flu 250 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | 2 | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+15) (+SCB) | Alive (mo+32) | EBV (rituximab) RTI (enterovirus/rhinovirus, ADV) | |

| 42 | 12 | MMFD | 7/10 | PBSC | No | None | None | PtCY d+3/+4 Tacro/MMF | No | No | SCB (mo+3) | Alive (mo+45) | ||

| 43 | 22 | MMFD | 6/10 | PBSC | Yes TCRab/CD19 | Treo 42 Flu 150 Thio 10 (MAC) | ATG-T 5 | Tocilizumab abatacept rituximab | No | No | CD45RA deplet. DLI (d+47, +81, +94) | Alive (mo+63) | RTI (HHV6, RSV) GI (RV, HHV6, ADV) Sepsis (Candida) Disseminated BCG | Arthritis |

| 44‡ | 37 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 75 Flu 160 (MAC) | ATG-T 7.5 | CSA/MMF | No | NA | Died (d+15) | MAS | ||

| 45 | 23 | MMFD | 5/10 | PBSC | Yes TCRab/CD19 | Treo 42 Flu 150 TT 10 (MAC) | ATG-G 30 | MMF, pred, ruxolitinib, vedolizumab | Yes, skin, 2 | No | Alive (mo+12) | EBV infection GI NV Zoster (VZV) RTI (rhinovirus/enterovirus, BV) | ||

| 46 | 3 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 79 Flu 180 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MMF | No | No | Alive (mo+85) |

| ID . | Age at HSCT (mo) . | Donor . | HLA . | Graft . | T-cell depletion∗ . | Conditioning† . | Serotherapy . | GVHD prophylaxis . | Acute GVHD . | Chronic GVHD . | Post-HSCT CT . | Outcome (mo/d after HSCT) . | Complications >HSCT . | AID >HSCT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‡ | 35 | MMFD | 3/6 | BM | Yes | Bu 16 Cy 200 TT 20 (MAC) | None | None | 2 | NA | Died (d+49) | ADV | ||

| 2 | 26 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 20 Flu 200 (MAC) | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+156) | |||

| 3 | 51 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 16 Flu 120 (MAC) | None | CSA | 3 | Yes | Alive (mo+125) | |||

| 4‡ | 35 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 19.2 Flu 160 Cy 120 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | 2 | Yes | Died (mo+33) | Sepsis/meningitis (chronic extensive GVHD) | ||

| 5 | 14 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 19.2 Flu 160 Cy 120 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+84) | |||

| 6 | 10 | MMFD | 3/6 | PBSC | Yes | Bu 16 Flu 160 TT 10 (MAC) | None | None | No | No | Alive (mo+70) | |||

| 7 | 27 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | None | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+221) | Disseminated BCG Psoas abscess | AIHA | |

| 8 | 16 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 20 Cy 200 (MAC) | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+151) | |||

| 9 | 14 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 16 Flu 160 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+114) | |||

| 10 | 25 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-G 20 | CSA | 1 | Yes | Alive (mo+161) | |||

| 11 | 6 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-G 20 | CSA | 3 | Yes | DLI (d+73) | Alive (mo+98) | RTI Klebsiella, pancytopenia | |

| 12 | 72 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Bu 12.8 Cy 120 (MAC) | ATG-G 40 | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+126) | |||

| 13 | 20 | MMFD | 4/6 | PBSC | Yes CD34+pos | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-T 20 | None | 1 | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+14) | Alive (mo+260) | AIHA§ ITP§ | |

| 14 | 47 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MTX | 1 | No | Alive (mo+192) | VZV (zoster) | ||

| 15 | 39 | MFD | 6/6 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MMF | 3 | No | Alive (mo+137) | Pneumatosis intestinalis | ||

| 16 | 2 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | 2 | No | SCB (mo+9) | Alive (mo+240) | VOD, pneumonitis, nephritis | AIHA§ Alopecia totalis§ |

| 17 | 39 | MFD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/ MMF | 3 | No | Alive (mo+65) | |||

| 18 | 25 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Bu 16 Flu 160 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX/ rituximab | No | No | Alive (mo+87) | VOD, pneumonitis | ||

| 19 | 22 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA | No | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+41) | Alive (mo+62) | ||

| 20 | 168 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | ATG-T 10 | CSA/ MMF | No | No | Alive (mo+28) | |||

| 21 | 28 | UCB | 5/6 | UCB | No | Treo 42 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 0.3 | CSA/ MMF | No | Yes | Alive (mo+20) | |||

| 22 | 25 | MFD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | None | CSA/ MTX | 2 | Yes | Alive (mo+125) | |||

| 23 | 42 | MFD | 6/6 | BM | No | Treo 42 Flu 160 TT 8 (MAC) | None | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+22) | |||

| 24 | 12 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Treo 42 Flu 160 (RIC) | ATG-G 45 | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+94) | |||

| 25‡ | 31 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MMF | 4 | NA | SCB | Died (mo+8) | Acute relapsing GVHD (gut) | |

| 26 | 7 | MUD | 9/10 | PBSC | Yes CD34+pos | Treo 36 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MMF | 1 | No | Alive (mo+72) | |||

| 27 | 36 | MFD | 6/6 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Flu 150 (MAC) | None | CSA | No | No | Alive (mo+156) | VZV (zoster) | ||

| 28 | 40 | UCB | 6/6 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | None | CSA/Pred | No | No | Alive (mo+96) | |||

| 29‡ | 22 | UCB | 10/10 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Flu 140 Mel 70 (MAC) | ATG-T 10 | CSA/Pred | No | NA | Died (d+20) | Neurologic decline | ||

| 30 | 20 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 80 Flu 150 (MAC) | ATG-T 10 | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+108) | RTI (ADV, PIV3, metapneumovirus) | ||

| 31 | 18 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Mel 140 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 1 | CSA/MMF | 1 | Yes | Alive (mo+24) | |||

| 32 | 192 | MMFD | 3/6 | PBSC | Yes TCRab/CD19 | Treo 42 Flu 150 TT 10 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.3 | None | 2 | No | Alive (mo+28) | GI (ADV, NV) RTI (Covid-19) | ||

| 33 | 43 | UCB | 5/6 | UCB | No | Bu 16 Cy 200 (MAC) | ATG-E 90 | CSA/pred | No | Yes | Alive (mo+156) | AIHA§ ITP§ DM Graves disease | ||

| 34 | 119 | UCB | 4/6 | UCB | No | Flu 125 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 2.3 | Tacro MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+96) | |||

| 35 | 92 | UCB | 6/6 | UCB | No | Flu 125 Mel 140 (RIC) | Alemt. 2.4 | Tacro/MTX | 2nd HSCT (mo+5) | Autologous recovery | VZV (zoster) RTI by EBV | |||

| 36‡ | 52 | UCB | 5/6 | UCB | No | Flu 150 Mel 140 TT 7 (MAC) | Alemt. 3.2 | Tacro/MTX | 3 | NA | Died (mo+8.5) | ADV, CMV (acute relapsing GVHD) | ||

| 37 | 2 | MMFD | 7/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 55 Cy 20 Flu 150 (RIC) | Alemt. 0.4 | PtCY d+3/+4 Tacro/MMF | No | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+17) | Alive (mo+80) | EBV (rituximab) RTI (Aspergillus) | AIHA |

| 38 | 4 | MUD | 9/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 79 Flu 160 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MMF | 3 | No | Alive (mo+53) | VOD | ||

| 39 | 41 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Bu 12 Flu 250 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | No | No | Alive (mo+30) | EBV+PTLD (rituximab) GI (sapovirus) Neisseria bacteremia | ||

| 40 | 26 | MUD | 9/10 | PBSC | No | Bu 12 Flu 250 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | 2 | No | Alive (mo+22) | EBV (rituximab) RTI (rhinovirus/enterovirus/CV) GI (sapovirus) | ||

| 41 | 4 | MUD | 10/10 | PBSC | No | Bu12 Flu 250 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MTX | 2 | No | 2nd HSCT (mo+15) (+SCB) | Alive (mo+32) | EBV (rituximab) RTI (enterovirus/rhinovirus, ADV) | |

| 42 | 12 | MMFD | 7/10 | PBSC | No | None | None | PtCY d+3/+4 Tacro/MMF | No | No | SCB (mo+3) | Alive (mo+45) | ||

| 43 | 22 | MMFD | 6/10 | PBSC | Yes TCRab/CD19 | Treo 42 Flu 150 Thio 10 (MAC) | ATG-T 5 | Tocilizumab abatacept rituximab | No | No | CD45RA deplet. DLI (d+47, +81, +94) | Alive (mo+63) | RTI (HHV6, RSV) GI (RV, HHV6, ADV) Sepsis (Candida) Disseminated BCG | Arthritis |

| 44‡ | 37 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 75 Flu 160 (MAC) | ATG-T 7.5 | CSA/MMF | No | NA | Died (d+15) | MAS | ||

| 45 | 23 | MMFD | 5/10 | PBSC | Yes TCRab/CD19 | Treo 42 Flu 150 TT 10 (MAC) | ATG-G 30 | MMF, pred, ruxolitinib, vedolizumab | Yes, skin, 2 | No | Alive (mo+12) | EBV infection GI NV Zoster (VZV) RTI (rhinovirus/enterovirus, BV) | ||

| 46 | 3 | MUD | 10/10 | BM | No | Bu cAUC 79 Flu 180 (MAC) | Alemt. 0.6 | CSA/MMF | No | No | Alive (mo+85) |

ADV, adenovirus; Alemt., alemtuzumab (mg/kg body weight); ATG-E, horse anti–thymocyte globulin (mg/kg body weight); ATG-G, rabbit anti–T-lymphocyte globulin (mg/kg body weight); ATG-T, rabbit antithymocyte globulin (mg/kg body weight); Bu, busulfan (mg/kg body weight); BV, bocavirus; cAUC, cumulative area under the curve (mg/L × h); CSA, cyclosporine A; CV, coronavirus; Cy, cyclophosphamide; DM, diabetes mellitus; Flu, fludarabine (mg/m2 body surface area); GI, gastrointestinal infection; Mel, melphalan; MFD, matched family donor; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MMFD, mismatched family donor; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable; NV, norovirus; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells; PIV3, parainfluenza virus type 3; Pred, prednisolone; PtCY, post-HSCT cyclophosphamide; PTLD, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease; RTI, respiratory tract infection; Tacro, tacrolimus; TCRab, T-cell receptor αβ; Treo, treosulfan (g/m2 body surface area); TT, thiotepa (mg/kg body weight); VOD, veno-occlusive disease; UCB, umbilical cord blood.

In vitro depletion.

Definitions of conditioning (supplemental Material).

Deceased patient.

Resolved after rituximab treatment.

One patient developed primary GF and 4 patients developed secondary GF, both occurring after MAC and RIC conditioning. There was no difference in the OS among those who received RIC conditioning,34 those who received no conditioning,44 and those who received MAC conditioning, but higher rates of a second HSCT (24%; 4/17) and additional secondary CT, eg, DLI (n = 1) and SCB (n = 2) (41%; 7/17), were observed in the RIC/no conditioning group, whereas the CT rate was lower in the MAC group (1 DLI, second HSCT, and SCB; 10%; 3/29).

All patients with GF underwent a second HSCT with 2 of the patients receiving grafts from the primary donors (haploidentical, matched unrelated donor [MUD]) and 3 patients receiving grafts from secondary donors (2 MUD, 1 haploidentical). For reconditioning chemotherapy, RIC (n = 4) and MAC (n = 1) conditioning regimens were administered. No GF or acute or chronic GVHD was observed after the second HSCT, and all patients survived (Table 3; supplemental Table 3).

GHVD and other complications

No unusual toxicities were reported after conditioning for the primary or secondary HSCTs with the exception of 2 episodes of nonlethal hepatic veno-occlusive disease. Acute GVHD grade 2 to 4 was observed in 13 (30%) patients and grade 3 to 4 was observed in 7 (16%) patients. Among the surviving patients, chronic limited GVHD was observed in 7 (16%) patients, and none had extensive GVHD.

Among the patients who died, 3 patients had either chronic extensive (patient 4) or acute relapsing GVHD (patients 25 and 36); 2 of them died as a consequence of infections (adenovirus and sepsis/meningitis) (Table 3).

A total of 24% (11/46) of patients had relevant infections, including viral infections, eg, adenovirus, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6), CMV, EBV, VZV, rotavirus, sapovirus, enterovirus/rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, and SARS-CoV-2. Bacterial infections included Clostridium difficile, Klebsiella pneumoniae, viridans group streptococci, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), whereas the fungal infections were caused by Aspergillus sp. and Candida sp. In 4 cases, EBV reactivation required rituximab administration. All of these infections resolved (Table 3).

Secondary AIDs were observed in 15% of patients (7/46), including AIHA (3/46) and Evans syndrome (2/46), Graves disease, macrophage activation syndrome, arthritis, alopecia totalis, and diabetes mellitus. All episodes of secondary autoimmune cytopenia resolved after intensified immunosuppression, including rituximab (Table 3; supplemental Table 3).

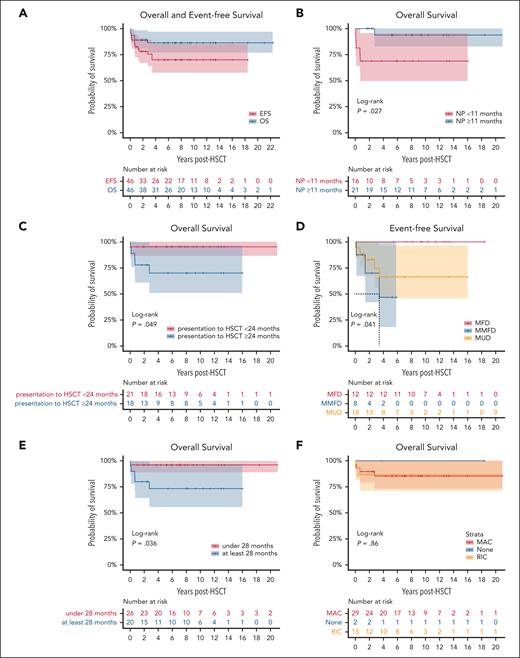

Survival

After a median follow-up period of 7.9 years (1.0-22.3), the 3-year OS and EFS probabilities were 86% (95% CI, 77-97) and 75% (95% CI, 64-89), respectively. A total of 40 patients survived, whereas 6 patients died (13%). Five of these deaths occurred because of infections, whereas 1 patient succumbed to status epilepticus shortly after undergoing HSCT. Four patients passed away during the first year following HSCT, whereas 2 patients died >2 years after HSCT (Figure 2A; Table 3).

OS and EFS curves. Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating the OS following HSCT. (A) OS and EFS after HSCT. (B) OS based on age at neurologic presentation (NP) (<11 months vs ≥11 months). (C) OS stratified by time from diagnosis to HSCT (<24 months vs ≥24 months). (D) EFS based on donor type, namely matched family donor (MFD), mismatched family donor (MMFD), MUD. (E) OS by age at HSCT (<28 months vs ≥28 months). (F) OS according to conditioning regimen, namely MAC, RIC, or none.

OS and EFS curves. Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating the OS following HSCT. (A) OS and EFS after HSCT. (B) OS based on age at neurologic presentation (NP) (<11 months vs ≥11 months). (C) OS stratified by time from diagnosis to HSCT (<24 months vs ≥24 months). (D) EFS based on donor type, namely matched family donor (MFD), mismatched family donor (MMFD), MUD. (E) OS by age at HSCT (<28 months vs ≥28 months). (F) OS according to conditioning regimen, namely MAC, RIC, or none.

MSD/matched family donor transplants produced 100% disease-free survival (DFS). Unrelated donor and cord blood transplantation exhibited slightly lower success rates with 80.7% of patients experiencing DFS. Five of the 6 deaths occurred after MUD/mismatched unrelated donor (3/6) or UCB (2/6) transplantation. Haploidentical transplants demonstrated an 87.5% DFS rate, although the number of patients in this group was limited (8/46).

Patients diagnosed at birth and who underwent early HSCT (median age of 4 months) exhibited superior survival outcomes (100%) when compared with the rest of the cohort (84% CI, 74-97; P = .28; supplemental Figure 1R), suggesting that early diagnosis and HSCT can improve the overall outcomes, similar to what is seen in patients with SCID.45

Patients who underwent HSCT within 24 months after initial presentation demonstrated superior OS (95% CI, 87-100 vs 70% CI, 51-97; P = .049). Conversely, neurologic symptoms that occurred before 11 months of age were associated with reduced OS (69% CI, 49-96 vs 94% CI, 83-100; P = .027). Furthermore, patients who underwent HSCT at a younger age (before 28 months of age) exhibited improved OS (96% CI, 89-100 vs 73% CI, 56-97; P = .036). However, a contrasting trend toward poorer outcomes was observed in children who presented solely with neurologic symptoms (75% CI, 57-100 vs 92% CI, 83-100; P = .076). Graft source, gender, alkylator, RIC, MAC, time of initial clinical presentation, and presence of AID before HSCT did not have a significant influence on OS (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 1A-V).

Donor chimerism and immune restoration

At the last FU, all surviving patients had been weaned from immunosuppression and exhibited adequate T-cell numbers and function, which provided protection against opportunistic infections and cured secondary autoimmune cytopenia. In total, 85% of patients (34/40) have discontinued immunoglobulin replacement therapy, whereas 15% (6/40) patients remained on immunoglobulin replacement therapy; 4 of these patients have undergone previous rituximab treatment.

DC evaluation in whole blood was conducted at the last FU in 37 of the 40 (92,5%) surviving patients, including 5 patients who successfully underwent a second HSCT (supplemental Figure 3; supplemental Table 3). The DC analysis revealed that 68% (25/37) exhibited levels of >95%, 18% (7/37) demonstrated levels between 50% and 95%, and 14% (5/37) had levels of <50% (with at least 12%). The DC in CD15+ cells (neutrophils) was analyzed in 10 patients, revealing that 20% (2/10) exhibited levels of >95%, 20% (2/10) had levels of between 50% and 95%, and 40% (6/10) had levels <50% (with at least 5%). The analysis of DC in CD3+ cells (T cells) in 19 patients revealed that 42% (8/19) exhibited levels of >95%, 37% (9/19) demonstrated levels of between 50% and 95%, and 10.5% (2/19) showed levels <50% (at least 40%). The DC in CD19+/CD20+ (B cells) was analyzed in 13 patients, revealing that 31% (4/13) exhibited levels of >95%, 15% (2/13) had levels of between 50% and 95%, and 54% (7/13) had levels of <50% (with at least 3%).

Metabolic analyses were available in 67.5% (27/40) of patients of whom 9 had normalized urinary purine metabolites and 18 had normal or greater than 10% PNP enzyme activity. Our data were insufficient to correlate the normalization of urine metabolites and/or PNP enzymatic activity with a particular transplant approach (Table 4; supplemental Figure 3).

Donor cell chimerism and immune and metabolic parameters at last FU

| ID . | FU (mo) . | DC WBC (%) . | DC CD15+ (%) . | DC CD3+ (%) . | DC CD19+ (%) . | PNP enzyme activity∗/metabolites† . | CD3+ (per μL) . | CD4+/naïve CD4+45RA+ (per μL) . | CD8+ (per μL) . | PHA (SI) . | CD19 (per μL) . | IVIG (yes/no) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 2 | 156 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1655 | 750 | 750 | 228 | 325 | No |

| 3 | 125 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1050 | 470 | 545 | 461 | 235 | No |

| 4‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 5 | 84 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2920 | 1570 | 990 | 1016 | 1100 | No |

| 6 | 70 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 655 | 370 | 260 | 251 | 240 | No |

| 7 | 221 | 50 | 22 | 93 | ND | Metabolites normal | 1843 | 684 | 1064 | Normal | 8 | Yes |

| 8 | 151 | 100 | ND | 100 | 92 | Metabolites normal | 2410 | 1353 | 780 | Normal | 1271 | No |

| 9 | 114 | 95 | ND | 100 | ND | Metabolites normal | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Yes |

| 10 | 161 | 40 | ND | 83 | ND | ND | 13 300 | 1260 | 11 080 | Normal | 280 | No |

| 11 | 98 | 90 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1796 | 949/92 | 847 | ND | 338 | No |

| 12 | 160 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1160 | 499 | 549 | ND | 420 | No |

| 13§ | 268 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 670 | 370/70 | 230 | ND | 120 | No |

| 14 | 192 | 35 | 11 | 85 | ND | ND | 1260 | 610/250 | 570 | 111 | 210 | No |

| 15 | 137 | 90 | 79 | 100 | 87 | PNP enzyme normal | 1340 | 720/430 | 530 | 220 | 170 | Yes |

| 16§ | 252 | 99 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1950 | 1546 | 371 | 516 | Normal | Yes |

| 17 | 65 | ND | 5 | 100 | 20 | ND | 3690 | 258 | 2331 | Normal | 111 | No |

| 18 | 87 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 3691 | 1678 | 1918 | Normal | 881 | No |

| 19 | 62 | 48 | ND | 44 | ND | ND | 868 | 468 | 369 | ND | 233 | No |

| 20 | 28 | 99 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1335 | 427 | 836 | ND | 267 | No |

| 21 | 20 | 96 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | No |

| 22 | 125 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | No |

| 23 | 112 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1796 | 929/543 | 683 | Normal | 521 | No |

| 24 | 94 | 70 | ND | 80 | 60 | ND | 2950 | 1621/1149 | 993 | ND | 315 | No |

| 25‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 26 | 72.0 | 70 | 73 | 75 | 50 | PNP enzyme normal | 1650 | 750 | 570 | 235 | 280 | No |

| 27 | 156.0 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 3063 | 950/260 | 582 | Normal | 1623 | No |

| 28 | 96.0 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1648 | 914/548 | 642 | ND | 345 | No |

| 29‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 30 | 108 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 3455 | 1462/950 | 1123 | Normal | 670 | No |

| 31 | 24 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 700 | 40 | 250 | ND | 340 | Yes |

| 32 | 28 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | No | |

| 33 | 156 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1626 | 779/53 | 666 | Normal | 239 | No |

| 34 | 96 | 85 | 10 | 85 | 10 | ND | 341 | 203/30 | 124 | ND | 104 | No |

| 35 | 98 | 100 | ND | 100 | 100 | ND | 1636 | 1018/43 | 468 | ND | 650 | No |

| 36‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 37 | 80 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | Metabolites normal | 2220 | 1110/701 | 832 | 0.95 | 462 | No |

| 38 | 53 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Metabolites normal | 3072 | 2035/1608 | 768 | 0.9 | 653 | No |

| 39§ | 30 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | Metabolites normal | 2180 | 930 | 640 | Normal | 500 | No |

| 40§ | 22 | 99 | 98 | 95 | 96 | Metabolites normal | 980 | 252 | 340 | Normal | 260 | No |

| 41§ | 32 | ND | 5 | 77 | 3 | Metabolites normal | 1430 | 201 | 760 | Normal | Yes | |

| 42 | 45 | 12 | ND | 80 | 6 | Metabolites normal | 272 | 114/11 | 209 | Normal | 167 | No |

| 43 | 63 | 100 | ND | 100 | ND | Normal | Normal | Normal | ND | Normal | Yes | |

| 44‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 45 | 12 | 100 | ND | 100 | 100 | ND | 4580 | ND | 1860 | 34.7 | 1090 | No |

| 46 | 85 | 77 | ND | 79 | 45 | PNP enzyme normal | 1760 | ND | 750 | 1171 | 310 | No |

| ID . | FU (mo) . | DC WBC (%) . | DC CD15+ (%) . | DC CD3+ (%) . | DC CD19+ (%) . | PNP enzyme activity∗/metabolites† . | CD3+ (per μL) . | CD4+/naïve CD4+45RA+ (per μL) . | CD8+ (per μL) . | PHA (SI) . | CD19 (per μL) . | IVIG (yes/no) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 2 | 156 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1655 | 750 | 750 | 228 | 325 | No |

| 3 | 125 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1050 | 470 | 545 | 461 | 235 | No |

| 4‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 5 | 84 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2920 | 1570 | 990 | 1016 | 1100 | No |

| 6 | 70 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 655 | 370 | 260 | 251 | 240 | No |

| 7 | 221 | 50 | 22 | 93 | ND | Metabolites normal | 1843 | 684 | 1064 | Normal | 8 | Yes |

| 8 | 151 | 100 | ND | 100 | 92 | Metabolites normal | 2410 | 1353 | 780 | Normal | 1271 | No |

| 9 | 114 | 95 | ND | 100 | ND | Metabolites normal | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Yes |

| 10 | 161 | 40 | ND | 83 | ND | ND | 13 300 | 1260 | 11 080 | Normal | 280 | No |

| 11 | 98 | 90 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1796 | 949/92 | 847 | ND | 338 | No |

| 12 | 160 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1160 | 499 | 549 | ND | 420 | No |

| 13§ | 268 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 670 | 370/70 | 230 | ND | 120 | No |

| 14 | 192 | 35 | 11 | 85 | ND | ND | 1260 | 610/250 | 570 | 111 | 210 | No |

| 15 | 137 | 90 | 79 | 100 | 87 | PNP enzyme normal | 1340 | 720/430 | 530 | 220 | 170 | Yes |

| 16§ | 252 | 99 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1950 | 1546 | 371 | 516 | Normal | Yes |

| 17 | 65 | ND | 5 | 100 | 20 | ND | 3690 | 258 | 2331 | Normal | 111 | No |

| 18 | 87 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 3691 | 1678 | 1918 | Normal | 881 | No |

| 19 | 62 | 48 | ND | 44 | ND | ND | 868 | 468 | 369 | ND | 233 | No |

| 20 | 28 | 99 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1335 | 427 | 836 | ND | 267 | No |

| 21 | 20 | 96 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | No |

| 22 | 125 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | No |

| 23 | 112 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1796 | 929/543 | 683 | Normal | 521 | No |

| 24 | 94 | 70 | ND | 80 | 60 | ND | 2950 | 1621/1149 | 993 | ND | 315 | No |

| 25‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 26 | 72.0 | 70 | 73 | 75 | 50 | PNP enzyme normal | 1650 | 750 | 570 | 235 | 280 | No |

| 27 | 156.0 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 3063 | 950/260 | 582 | Normal | 1623 | No |

| 28 | 96.0 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1648 | 914/548 | 642 | ND | 345 | No |

| 29‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 30 | 108 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 3455 | 1462/950 | 1123 | Normal | 670 | No |

| 31 | 24 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 700 | 40 | 250 | ND | 340 | Yes |

| 32 | 28 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | No | |

| 33 | 156 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | PNP enzyme normal | 1626 | 779/53 | 666 | Normal | 239 | No |

| 34 | 96 | 85 | 10 | 85 | 10 | ND | 341 | 203/30 | 124 | ND | 104 | No |

| 35 | 98 | 100 | ND | 100 | 100 | ND | 1636 | 1018/43 | 468 | ND | 650 | No |

| 36‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 37 | 80 | 100 | ND | ND | ND | Metabolites normal | 2220 | 1110/701 | 832 | 0.95 | 462 | No |

| 38 | 53 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Metabolites normal | 3072 | 2035/1608 | 768 | 0.9 | 653 | No |

| 39§ | 30 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | Metabolites normal | 2180 | 930 | 640 | Normal | 500 | No |

| 40§ | 22 | 99 | 98 | 95 | 96 | Metabolites normal | 980 | 252 | 340 | Normal | 260 | No |

| 41§ | 32 | ND | 5 | 77 | 3 | Metabolites normal | 1430 | 201 | 760 | Normal | Yes | |

| 42 | 45 | 12 | ND | 80 | 6 | Metabolites normal | 272 | 114/11 | 209 | Normal | 167 | No |

| 43 | 63 | 100 | ND | 100 | ND | Normal | Normal | Normal | ND | Normal | Yes | |

| 44‡ | Died | |||||||||||

| 45 | 12 | 100 | ND | 100 | 100 | ND | 4580 | ND | 1860 | 34.7 | 1090 | No |

| 46 | 85 | 77 | ND | 79 | 45 | PNP enzyme normal | 1760 | ND | 750 | 1171 | 310 | No |

IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin dependent; ND, not done; Normal, testing of lymphocyte subpopulations, PHA mitogen stimulation, urinary purine metabolites within the normal range; PHA SI, phytohemagglutinin stimulation of lymphocytes; SI, stimulation index; WBC, white blood cells.

Erythrocyte PNP enzyme activity in untransfused patients.

Urinary purine metabolites (uric acid, deoxyguanosine triphosphate, guanosine, inosine, deoxyguanosine, and deoxyinosine).

Deceased patient.

Treated with rituximab.

Neurologic outcomes

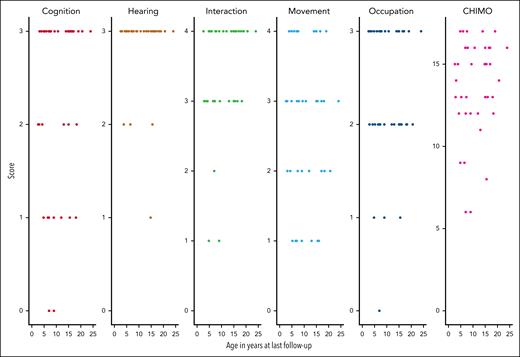

At the most recent FU, the treating physician evaluated the severity of neurologic symptoms and the CHIMO score and classified the results into 3 categories, namely improved (17/40; 42.5%), clinically stable (n = 16/40; 40%), or declined (n = 7/40; 17.5%). The median CHIMO score was determined to be 14 (range, 6-17), with medians of 3 (0-3) for cognition, 3 (1-3) for hearing, 4 (1-4) for interaction, 3 (1-4) for movement, and 2 (0-3) for occupation. The median Karnofsky and Lansky scores were 90% and 85%, respectively, with a range of 40% to 100% for both scores (Table 5; Figures 3 and 4). In most of our patients, no further neurologic deterioration occurred after HSCT once adequate engraftment of donor myeloid cells had been achieved. After a median FU period of >7 years following HSCT, most surviving patients had reached preschool/school age, thereby enabling more precise categorization of the category occupation within the CHIMO score. The analysis of CHIMO scores revealed that 50% (20/40) of patients attained the highest scores of between 15 and 17, whereas an additional 35% (14/40) scored within the range of 12 to 14. Conversely, 15% (6/40) of patients, were in the lowest score range of 6 to 11. All 6 patients who were diagnosed early by family history and who underwent early HSCT were alive and were assessed with a median CHIMO score of 14 (9-17) at a median FU of 63 months (Table 5), which was comparable with the median CHIMO score of 14 for the entire cohort. Four of these early-diagnosed patients received ET shortly after birth, which was reported to achieve measurable purine metabolite detoxification before HSCT.30 Although early detoxification until HSCT seems a rational approach for early-diagnosed patients with PNP,27 it was as yet impossible to determine whether this affects the long-term neurologic outcomes given the limited number of subjects.

Neurologic outcome and CHIMO score at last FU

| ID . | FU (mo) . | Cognition (score) . | Hearing (score) . | Interaction (score) . | Movement (score) . | Occupation (score) . | CHIMO (score) . | Karnofsky (score) . | Lansky (score) . | Neurologic evaluation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 2 | 156 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 100 | 100 | Stable |

| 3 | 125 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 100 | 100 | Stable |

| 4∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 5 | 84 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 40 | 40 | Stable |

| 6 | 70 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 50 | 50 | Stable |

| 7† | 221 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 50 | 70 | Improved |

| 8 | 151 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | 100 | Improved |

| 9 | 114 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | 100 | Stable |

| 10 | 161 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 50 | Stable | |

| 11 | 98 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 100 | Improved | |

| 12 | 160 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 | 100 | Stable | |

| 13 | 268 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | 90 | Stable |

| 14 | 192 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 80 | 90 | Improved |

| 15 | 137 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 100 | 100 | Stable |

| 16† | 252 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 40 | 100 | Declined |

| 17 | 65 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 70 | Stable | |

| 18 | 87 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | 100 | Improved |

| 19 | 62 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 70 | 100 | Improved |

| 20 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 90 | Improved | |

| 21 | 20 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 70 | Improved | |

| 22 | 125 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Stable | |

| 23 | 112 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 80 | Improved | |

| 24 | 94 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | Declined | |

| 25∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 26† | 72.0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 50 | 75 | Stable |

| 27 | 156.0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | Improved | |

| 28 | 96.0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 100 | Declined | |

| 29∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 30 | 108 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 70 | Stable | |

| 31 | 24 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 90 | 90 | Improved |

| 32 | 28 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 60 | Stable | |

| 33 | 156 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 90 | Stable | |

| 34 | 96 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Improved | |

| 35 | 98 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 15 | 90 | Improved | |

| 36∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 37† | 80 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 | 100 | Declined | |

| 38† | 53 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Stable | |

| 39 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Improved | |

| 40 | 22 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 100 | Improved | |

| 41† | 32 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 90 | Declined | |

| 42 | 45 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 70 | 90 | Declined |

| 43 | 63 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 60 | 70 | Improved |

| 44∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 45 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 50 | 70 | Improved |

| 46† | 85 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 40 | 70 | Declined |

| ID . | FU (mo) . | Cognition (score) . | Hearing (score) . | Interaction (score) . | Movement (score) . | Occupation (score) . | CHIMO (score) . | Karnofsky (score) . | Lansky (score) . | Neurologic evaluation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 2 | 156 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 100 | 100 | Stable |

| 3 | 125 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 100 | 100 | Stable |

| 4∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 5 | 84 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 40 | 40 | Stable |

| 6 | 70 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 50 | 50 | Stable |

| 7† | 221 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 50 | 70 | Improved |

| 8 | 151 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | 100 | Improved |

| 9 | 114 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | 100 | Stable |

| 10 | 161 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 50 | Stable | |

| 11 | 98 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 100 | Improved | |

| 12 | 160 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 | 100 | Stable | |

| 13 | 268 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | 90 | Stable |

| 14 | 192 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 80 | 90 | Improved |

| 15 | 137 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 100 | 100 | Stable |

| 16† | 252 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 40 | 100 | Declined |

| 17 | 65 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 70 | Stable | |

| 18 | 87 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | 100 | Improved |

| 19 | 62 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 70 | 100 | Improved |

| 20 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 90 | Improved | |

| 21 | 20 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 70 | Improved | |

| 22 | 125 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Stable | |

| 23 | 112 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 80 | Improved | |

| 24 | 94 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | Declined | |

| 25∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 26† | 72.0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 50 | 75 | Stable |

| 27 | 156.0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 90 | Improved | |

| 28 | 96.0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 100 | Declined | |

| 29∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 30 | 108 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 70 | Stable | |

| 31 | 24 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 90 | 90 | Improved |

| 32 | 28 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 60 | Stable | |

| 33 | 156 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 90 | Stable | |

| 34 | 96 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Improved | |

| 35 | 98 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 15 | 90 | Improved | |

| 36∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 37† | 80 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 | 100 | Declined | |

| 38† | 53 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Stable | |

| 39 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 100 | Improved | |

| 40 | 22 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 100 | Improved | |

| 41† | 32 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 90 | Declined | |

| 42 | 45 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 70 | 90 | Declined |

| 43 | 63 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 60 | 70 | Improved |

| 44∗ | Died | |||||||||

| 45 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 50 | 70 | Improved |

| 46† | 85 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 40 | 70 | Declined |

FU, follow-up (in months after HSCT).

Deceased patient.

Perinatal/antenatal diagnosis owing to family history (patients 37, 38, 41, and 46 had received red cell exchange transfusions after birth).

Distribution of CHIMO scores at last FU visit. Plot illustrating the distribution of CHIMO scores across different domains, namely cognition, hearing, interaction, movement, and occupation, as well as the overall CHIMO score. Scores are displayed for individual patients at their specific age at their respective time of FU for the assessment of the CHIMO score.

Distribution of CHIMO scores at last FU visit. Plot illustrating the distribution of CHIMO scores across different domains, namely cognition, hearing, interaction, movement, and occupation, as well as the overall CHIMO score. Scores are displayed for individual patients at their specific age at their respective time of FU for the assessment of the CHIMO score.

Severity of categorized symptoms before and after HSCT. Heat map depicting the severity scores of clinical symptoms before and after HSCT divided into the categories, namely neurology, infection, and autoimmunity. Scores were based on clinical descriptions and CHIMO scores (refer to the supplemental Material). Asterisk (∗) marks the 6 patients diagnosed perinatally by family history.

Severity of categorized symptoms before and after HSCT. Heat map depicting the severity scores of clinical symptoms before and after HSCT divided into the categories, namely neurology, infection, and autoimmunity. Scores were based on clinical descriptions and CHIMO scores (refer to the supplemental Material). Asterisk (∗) marks the 6 patients diagnosed perinatally by family history.

Discussion