In this issue of Blood, Herrmann et al1 present the largest study to date of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) for purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) deficiency. This comprehensive analysis is an invaluable contribution to the management of this rare inborn error of immunity (IEI).

Since the original description in 1976,2 ∼100 patients with PNP deficiency have been reported.3 PNP deficiency is an autosomal recessive IEI characterized by a progressive decline in the number and function of T cells and, in some cases, B cells. As a result, patients typically present at an early age with recurrent and severe bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. A few reported patients presented with autoimmune diseases or hematologic malignancies. The immunodeficiency is attributed to the accumulation of the PNP enzyme’s substrates and their derivatives, deoxyguanosine and deoxyguanosine triphosphate (dGTP), which disrupt important metabolic and immune pathways, leading to increased apoptosis of cells.4 Many patients also exhibit motor and developmental delays, which often precede the immunodeficiency. This implicates the metabolic abnormalities as an important factor in neurologic dysfunction.5

In contrast to adenosine deaminase severe combined immunodeficiency (ADA-SCID), which is a more prevalent IEI also caused by a defective enzyme in purine metabolism, newborn screening programs that rely on absent T-cell receptor excision circles often fail to identify infants with PNP deficiency. This is due to the milder and progressive T lineage defects in PNP deficiency. Supportive antimicrobial management may delay the development of infections; however, they do not provide a long-term solution, nor do they prevent progressive neurologic damage. Furthermore, and in contrast to ADA-SCID, dedicated enzyme replacement and gene therapy are not available for PNP deficiency, leaving HCT as the only definitive treatment option.

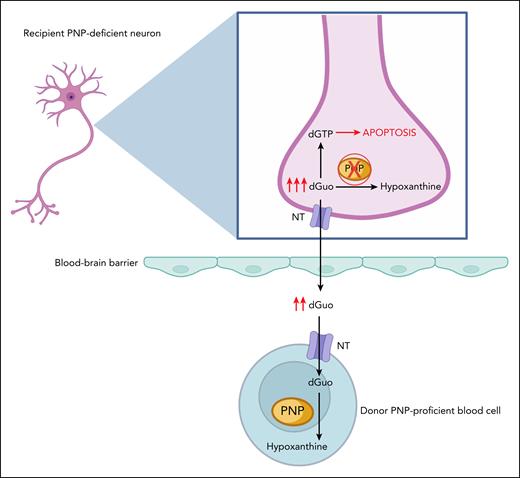

The few previous reports of HCT for PNP deficiency, mostly from single centers or with small numbers of cases with limited follow-up (FU), often demonstrated robust T-cell reconstitution after transplant, with conflicting descriptions regarding improvement in neurologic status.6,7 The mechanism behind the neurologic benefits of HCT were hypothesized to be related to the replacement of brain microglia with donor-derived PNP-proficient cells or the ability of donor blood cells to provide “cross-correction” (see figure) of the metabolic derangements.8

“Cross-correction” of PNP deficiency in neuronal cells after allogeneic HCT. In the recipient’s PNP-deficient neurons, the absence of functional PNP enzyme prevents the phosphorolysis of substrates such as deoxyguanosine (dGuo) into hypoxanthine, leading to accumulation of dGTP. This disrupts the cell’s metabolism and leads to the cell’s apoptosis. Excess dGuo can also exit the cell through transmembrane NT. After transplantation, excess dGuo is taken up by the donor PNP-proficient blood cell across the blood-brain barrier, following the concentration gradient of dGuo, where it can be further metabolized, eventually leading to the restoration of purine metabolism in the neuron. dGTP, deoxyguanosine triphosphate; NT, nucleoside transporters. Figure created with BioRender.com. Grunebaum E. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/689a34dde8409e308ef5ce82.

“Cross-correction” of PNP deficiency in neuronal cells after allogeneic HCT. In the recipient’s PNP-deficient neurons, the absence of functional PNP enzyme prevents the phosphorolysis of substrates such as deoxyguanosine (dGuo) into hypoxanthine, leading to accumulation of dGTP. This disrupts the cell’s metabolism and leads to the cell’s apoptosis. Excess dGuo can also exit the cell through transmembrane NT. After transplantation, excess dGuo is taken up by the donor PNP-proficient blood cell across the blood-brain barrier, following the concentration gradient of dGuo, where it can be further metabolized, eventually leading to the restoration of purine metabolism in the neuron. dGTP, deoxyguanosine triphosphate; NT, nucleoside transporters. Figure created with BioRender.com. Grunebaum E. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/689a34dde8409e308ef5ce82.

In an impressive effort by the Inborn Errors Working Party of the European Society For Blood And Marrow Transplanttion (EBMT), Herrmann et al conducted a retrospective study of 46 PNP-deficient patients who received HCT between 1998 and 2022 mostly in leading European centers.1 The neurologic outcome was evaluated using a novel scoring system, the Cognition, Hearing, Interaction, Movement, and Occupation (CHIMO) cumulative score.

In this cohort, PNP deficiency was diagnosed at a median age of 1.5 years, with some patients identified as late as 15.5 years, emphasizing the challenging diagnostic process. A similar number of patients presented exclusively with infectious symptoms or with neurological abnormalities, whereas a few patients (5%) presented with autoimmune manifestations. Within the group of patients who experienced infectious symptoms, varicella-zoster virus was a common pathogen associated with significant morbidity, especially beyond infancy.

Most patients underwent HCT within a few months to 1 year after diagnosis. Nevertheless, the rate of neurological abnormalities increased from 41% at the time of presentation to 88% at the time of HCT. Patients with PNP deficiency underwent HCT mostly from HLA-matched family or matched unrelated donors, using bone marrow or peripheral blood cells, often with myeloablative or reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) and in vivo T-cell depletion for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis and to prevent rejection.

Remarkably, after a median FU of nearly 8 years, the 3-year overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (defined as alive without second HCT or clinical relapse) were 86% and 75%, respectively. Six patients died, mostly in the first year after HCT due to infections or GVHD. Patients diagnosed at birth and those who underwent HCT more promptly (<2 years from presentation) exhibited superior OS, indicating that early diagnosis and definitive treatment can improve overall outcome. In contrast, presenting with neurologic symptoms at a young age was associated with reduced OS, possibly reflecting a more severe phenotype or existence of significant comorbidities. All surviving patients, including the 5 who required a second HCT, often after RIC, exhibited adequate T-cell numbers and function, whereas B-cell engraftment and function appeared more variable.

At the most recent FU, the neurologic symptoms were classified as improved or stable in 42.5% and 40% of the patients, respectively, although in many patients, cognition, movement, and preschool/school performance remained atypical. Importantly, most patients experienced no further neurological deterioration after HCT, even if donor engraftment was incomplete. These findings suggest that residual PNP activity by a small number of engrafted cells may be sufficient for immune and metabolic recovery and support observations in a few patients with partial PNP deficiency.9

Strengths of the study include the relatively large number of patients with PNP deficiency enrolled, compared to previous reports, and the extensive details provided on patients, HCT procedures, and outcomes. Other strengths include the relatively long FU period and the attempt to establish a relevant and quantifiable neurologic assessment. Limitations of the study include the retrospective design leading to incomplete data availability, as well as the absence of data on patients with PNP deficiency who did not receive HCT. Other caveats are the small number of patients who received HCT with newer GVHD management strategies and the utilization of the CHIMO cumulative score, which has not yet been validated.

In conclusion, this landmark study by Herrmann et al confirms that timely HCT can efficiently correct the immune defects caused by PNP deficiency and stabilize the neurologic abnormalities. Therefore, this study is of tremendous importance to families and health care providers managing patients with PNP deficiency who are considering HCT.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal