Key Points

TL1A-Ig+low-dose IL-2 pre-HSCT induces Treg expansion persisting early post-HSCT, diminishing GVHD, improving outcomes, and maintaining GVL.

TL1A-Ig+low-dose IL-2 pretreatment increases the frequency of tissue resident, functionally active Tregs in GVHD target tissues.

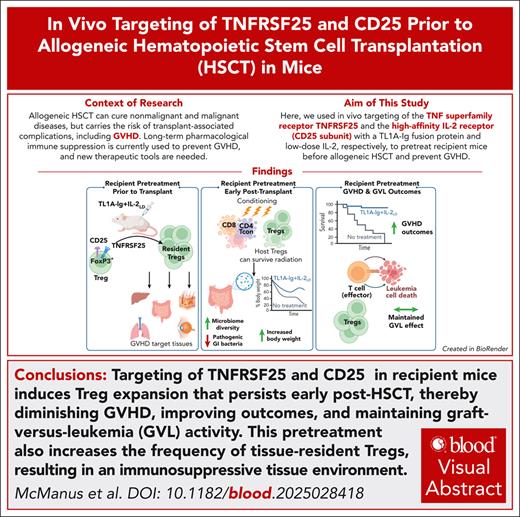

Visual Abstract

The current approach to minimize transplant-associated complications, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) includes long-term pharmacological immune suppression frequently accompanied by unwanted side effects. Advances in targeted immunotherapies regulating alloantigen responses in the recipient continue to reduce the need for pan-immunosuppression. Here, in vivo targeting of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily receptor TNFRSF25 (also known as DR3) and the high-affinity interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor with a TL1A-immunoglobulin (TL1A-Ig) fusion protein and low-dose IL-2, respectively, was used to pretreat recipient mice before allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT). Pretreatment induced regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion persisting 1 to 2 weeks after HSCT, leading to diminished GVHD and improved transplant outcomes. Expansion was accompanied by an increase in the frequency of stable and active Tregs, creating a suppressive tissue environment in the colon, liver, and eye. Importantly, pretreatment supported epithelial cell function/integrity, a diverse microbiome including reduction of pathologic bacteria outgrowth, and promotion of butyrate producing bacteria, while maintaining physiologic levels of obligate/facultative anaerobes. Notably, using a sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist to sequester T cells in lymphoid tissues, it was found that the increased tissue Treg frequency included resident CD69+CD103+FoxP3+ hepatic Tregs. In contrast to infusion of donor Tregs, the strategy developed here resulted in the presence of immunosuppressive target tissue environments in the recipient before the receipt of donor allogeneic-reactive T cells and successful perseveration of graft-versus-leukemia responses. We posit strategies that circumvent the need of producing large numbers of ex vivo manipulated Tregs may be accomplished through in vivo recipient Treg expansion, providing translational approaches to improve aHSCT outcomes.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT) is a curative procedure for patients with nonmalignant and malignant disorders.1 However, a serious complication of aHSCT is graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a donor T-cell–mediated inflammatory process predominantly targeting the skin, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and liver.2-4 Clinically, GVHD prevention and treatment consists of pharmacological regimens, which are pan-immunosuppressive, placing patients at an increased risk for disease relapse or infectious complications. Additionally, many immunosuppressants have off-target effects, causing other organ toxicities.5,6 As a potentially life-threatening complication, GVHD must be suppressed. However, maintaining graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) activity is critical to prevent tumor relapse.

Newer and alternative strategies to treat GVHD while preserving GVL have been the focus of current experimental and clinical research efforts. Several recently approved US Food and Drug Administration compounds including kinase inhibitors and T-cell activation regulators selectively target immune cells and show reduced drug toxicities.7-14 Immunotherapy is another strategy that may induce tolerance by manipulating regulatory immune cell populations. One such population shown to ameliorate GVHD is regulatory T cells (Tregs). Tregs, shown in experimental and clinical studies, can ameliorate GVHD across complete major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched aHSCT animal models and improve clinical symptoms of chronic GVHD in patients.15,16 To date, Treg-based immunotherapeutic approaches for GVHD have primarily focused on the use of donor-derived Tregs.15,17-21 Although trials of adoptive Treg therapy in both preclinical and clinical aHSCT demonstrate safety and efficacy, there are significant challenges using adoptive Treg therapy, such as difficulties in generating sufficient Treg numbers and potentially reduced Treg stability. This may limit their use in individual transplants and off-the-shelf applicability.15,18,22-29

Notably, Tregs are more radiotherapy/chemotherapy resistant than conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which likely contributes to a relative Treg enrichment early after aHSCT.17,30-35 Recent studies show patient-derived recipient T cells, including Tregs, residing in GVHD target tissues survive conditioning.36,37 These T cells were able to proliferate and were functionally competent >1 year post-aHSCT.36,37 We previously reported that recipient Tregs constitute the predominant component of the CD4+FoxP3+ compartment in the lymph nodes (LNs) for a number of weeks after radiotherapy conditioning and autologous HSCT. Importantly these Tregs exhibit suppressive function.38 Therefore, we propose that in vivo expansion of Tregs in recipients before conditioning and aHSCT may be a useful strategy to diminish GVHD in target tissues and ameliorate overall disease. Here, we report a new strategy in which aHSCT recipients treated with compounds targeting and stimulating the tumor necrosis factor superfamily receptor TNFRSF25 and the high-affinity interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor only before transplantation, expanding Tregs. This elevated recipient Treg frequency persisted for several weeks after aHSCT, particularly in nonhematopoietic target tissues. The elevated ratio of Tregs to conventional T cells (Tconv) was associated with suppressive environments as demonstrated by in vitro analyses and significant survival with diminished clinical GVHD. Importantly, GVL was maintained in recipients with greater Treg levels using an acute myeloid leukemia model. In total, these findings support the notion that pretransplant manipulation of the recipient Treg compartment may be an effective therapeutic approach for GVHD prophylaxis while maintaining GVL.

Methods

Mice

BALB/c (H2d) mice were purchased from Taconic or The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6J, B6-CD45.1, B6-FoxP3RFP, C3H.SW (H2b), and BALB/c-FoxP3DTR (H2d) mice were bred in our facility. BALB/cTNFRSF25−/− (H2d) were provided by J.-H.P. (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health).39 Mice (6-12 weeks old) were maintained in pathogen-free conditions at the University of Miami animal facilities.

Flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting

All antibodies used are listed in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from selected tissues/organs. Peripheral blood (PB) was collected in heparinized tubes and PB mononuclear cells were isolated using Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Cell surface and intracellular antibody staining was performed as previously described.40 Samples were run using either the LSR-Fortessa-HTS instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or a Cytek-Aurora (Cytek Biosciences, Bethesda, MD). Analysis was performed with FlowJo software (version 10.4.1, FlowJo, Ashland, OR). Flow Cytometry Standard files from aHSCT recipients with and without GVHD underwent terraFlow multistep pipeline unbiased analysis for summarization of key differences between groups.41

aHSCT and GVL

aHSCT was performed with sex- and age-matched mice using either a major MHC-mismatch (B6→BALB/c) or a minor MHC-mismatch (C3H.SW→B6) model. Recipient mice received total body irradiation (TBI) conditioning: day −1 (7.5 Gy) for major, or day 0 (10.5 Gy) for minor MHC mismatch. Transplantation was performed on day 0 for both models with T-cell–depleted (TCD) bone marrow (BM), as described previously.15 Major MHC-mismatch recipients received (5.5 × 106) TCD BM cells with or without (5.5 × 105) splenic T cells, and minor MHC-mismatch recipients received (7 × 106) TCD-BM cells with or without (2.0 × 106) splenic CD8+ T cells IV. Each recipient was monitored 3 times per week for GVHD, assessing overall survival, total body weight, and clinical score.15

For GVL assessment, BALB/c mice received 5 × 103 BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP at the time of aHSCT (day 0) examining tumor burden by green fluorescence protein–positive (GFP+) cell frequency from the blood and selected tissues on day of euthanasia, using flow cytometry.

TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD in vivo administration

TL1A-immunoglobulin (TL1A-Ig) was generated as previously described.42 Our Treg expansion protocol consists of TL1A-Ig (40 μg per mouse in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) given intraperitoneally (IP) daily on days 1 through 4 and recombinant human IL-2 (10 000 units [in PBS] per mouse) given IL daily on days 4 through 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

In vivo FTY720 administration

In vitro suppression assay

CD4+ cells were enriched from liver and lung cell isolates using the EasySep PE Positive Selection Kit II (catalog no. 17684; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and CD4-phycoerythrin. Unfractionated single-cell suspensions of conjunctiva and lacrimal gland were used in some experiments. Cells were cultured in 96-well plates and activated with 1 μg soluble anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb; Clone-2C11). Cell cultures were imaged using an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, White Plains, NY) obtaining brightfield images at ×40 magnification using a Keyence (Itasca, IL) BZ-X710 microscope and counted by trypan blue exclusion using Countess 3 automated cell counter (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) after 120 hours.

Spatial biology analysis using CODEX

Colons were collected from mice that received a complete MHC mismatched aHSCT on day +24; one group received TCD BM only, and another group received TCD BM plus 0.5 × 106 splenic T cells. Colons were flushed of stool using cold PBS. A 0.5-cm segment of the transverse colon was cut and placed perpendicularly into cryostat cassettes for optimal cutting temperature embedding and flash frozen. The tissue was sectioned transversely at 7 μm and processed per the Akoya preantibody staining, tissue staining, and poststaining procedures, using barcoded antibodies and corresponding barcode reporters listed in supplemental Table 2. The Pheno-Cycler-Fusion software and instrument performed iterative, whole-slide imaging creating a high resolution qpTIFF file. This was later used in the QuPath (version 0.5.1) environment to generate single-cell annotations determining cell nuclei and cell boundaries. The generated single-cell annotations and ultra-high parameter fluorescent data were exported to a csv file and used in R (Big Sur Intel build [8462]), R Studio (version 2024.4.2) and the Seurat package (version 5.0.3) to determine associated single-cell phenotypic markers, dimensionality reduction, and data visualizations.

Microbiome analysis

Stool samples from mice after aHSCT were taken on days −8, −1, 0, +1, + 7, +14, +21, and +28, from MHC-mismatched recipients. DNA from stool was extracted and purified by bead-beating in phenol-chloroform, as previously described.45-47 Genomic 16S ribosomal RNA V4/V5 regions were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and sequenced on the Illumina platform. Sequences were mapped and assigned taxonomically, as previously described.45-47 The microbial classification of predicted bacterial oxygen metabolism was adapted from Magnúsdóttir et al (supplemental Table 3).48 Bacteria were classified at the genus level when all species within that genus belonged to the same oxygen-metabolism group, and classified at the species level when diverse metabolic groups were found within the same genus. A list of predicted butyrate producers was adapted from Haak et al.49

Statistical analysis

The number of animals per group is described in the legends. All nonspatial biology graphing and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA). Values shown in graphs represent the mean of each group ± standard error of the mean. Survival data were analyzed with the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Nonparametric unpaired 2-tailed t test was used for comparisons between 2 experimental groups. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey multiple-comparison test was used between ≥3 experimental groups. A P value < .05 was considered significant, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

All animal use procedures were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

Expansion of Tregs before conditioning alters CD4+FoxP3+ frequency after TBI in the colon and peripheral lymphoid compartments

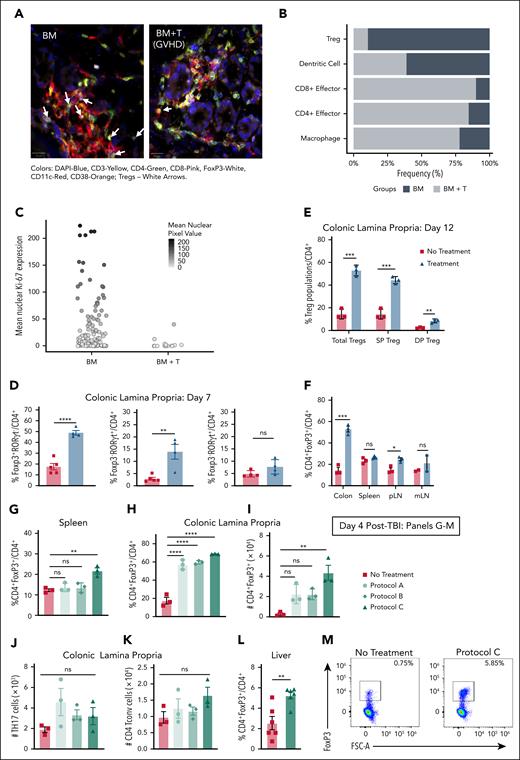

As previously reported, Treg frequency is diminished in the blood of patients with chronic GVHD (supplemental Figure 1A).16 Using spatial biological analysis, we found Treg frequency differences in colonic tissues of mice at day +24 after aHSCT. Colon mononuclear cell assessment indicated significantly elevated levels of lymphocytes and macrophages but decreased levels of Tregs in BALB/c mice with GVHD that had received transplantation with BM + T cells, vs mice without GVHD that only received BM transplantation (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figure 1B-D). This was accompanied by a significant reduction of Treg proliferation as determined by decreased Ki-67 expression (Figure 1C).

Optimizing in vivo Treg expansion protocol with TL1A-Ig+IL2LD for Treg survival after radiation. (A) qpTIFF CODEX images illustrating a subset of cell populations (7 selected markers) highlighting diminished Treg numbers in colonic tissue from BALB/c mice transplanted with BM + T cells experiencing GVHD vs BM transplanted alone; white arrows show Treg locations in the images. (B) Select immune cell frequencies separated by non-GVHD (BM only, black bars) and GVHD (BM + T cells, gray bars) from the whole colonic tissue, n = 2 per group. (C) Mean nuclear Ki-67 expression of Tregs separated by groups. Mice without GVHD (BM alone) contained a greater number of Tregs than animals with GVHD (BM+T) with ∼45% (compared with 0% in mice without GVHD) having moderate to high Ki-67 expression indicating proliferation. (D) BALB/c mice were treated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. Treg expansion in colonic LP at day 7 without detectable increase in colonic TH17 CD4+ T cells is shown. (E-F) BALB/c mice were assessed on day 12, 6 days after completing TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment. (E) The colon LP shows a persistence in elevated total Tregs as well as Treg subsets (SP: CD4+FoxP3+RORγt-; DP: CD4+FoxP3+RORγt+) at day 12, and (F) this persistence is greatest in the colon vs other tissues. (G-M) BALB/c mice were treated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD using different protocols (supplemental Figure 2C) and received TBI (8.5 Gy) on day −1. On day 4, immune cells were assessed for Treg frequencies in the spleen (G) and colonic LP (H). Protocol C demonstrated significantly higher Treg frequencies and numbers than protocols in panels A-B, and no treatment (panels G-I). Protocol C also shows no difference in TH17 (J) and CD4+ Tconv (K) numbers of the colon LP. Panels E-K: data points represent individual animals. (L-M) The liver exhibited a greater Treg frequency (L) when using protocol C. (M) Representative flow cytometry plots gating of CD4+FoxP3+Treg cells using cell isolates from the liver. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FSC-A, forward scatter-area; mLN, mesenteric lymph nodes; ns, not significant; pLN, peripheral lymph nodes; T, T cells.

Optimizing in vivo Treg expansion protocol with TL1A-Ig+IL2LD for Treg survival after radiation. (A) qpTIFF CODEX images illustrating a subset of cell populations (7 selected markers) highlighting diminished Treg numbers in colonic tissue from BALB/c mice transplanted with BM + T cells experiencing GVHD vs BM transplanted alone; white arrows show Treg locations in the images. (B) Select immune cell frequencies separated by non-GVHD (BM only, black bars) and GVHD (BM + T cells, gray bars) from the whole colonic tissue, n = 2 per group. (C) Mean nuclear Ki-67 expression of Tregs separated by groups. Mice without GVHD (BM alone) contained a greater number of Tregs than animals with GVHD (BM+T) with ∼45% (compared with 0% in mice without GVHD) having moderate to high Ki-67 expression indicating proliferation. (D) BALB/c mice were treated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. Treg expansion in colonic LP at day 7 without detectable increase in colonic TH17 CD4+ T cells is shown. (E-F) BALB/c mice were assessed on day 12, 6 days after completing TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment. (E) The colon LP shows a persistence in elevated total Tregs as well as Treg subsets (SP: CD4+FoxP3+RORγt-; DP: CD4+FoxP3+RORγt+) at day 12, and (F) this persistence is greatest in the colon vs other tissues. (G-M) BALB/c mice were treated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD using different protocols (supplemental Figure 2C) and received TBI (8.5 Gy) on day −1. On day 4, immune cells were assessed for Treg frequencies in the spleen (G) and colonic LP (H). Protocol C demonstrated significantly higher Treg frequencies and numbers than protocols in panels A-B, and no treatment (panels G-I). Protocol C also shows no difference in TH17 (J) and CD4+ Tconv (K) numbers of the colon LP. Panels E-K: data points represent individual animals. (L-M) The liver exhibited a greater Treg frequency (L) when using protocol C. (M) Representative flow cytometry plots gating of CD4+FoxP3+Treg cells using cell isolates from the liver. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FSC-A, forward scatter-area; mLN, mesenteric lymph nodes; ns, not significant; pLN, peripheral lymph nodes; T, T cells.

Administration of TL1A-Ig + low-dose IL-2 (TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD) induces a strong expansion of Tregs in the blood, spleen, and LNs of normal mice.15,50 Colonic lamina propria (LP) of mice receiving TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD exhibited a marked increase in CD4+FoxP3+RORγt− and CD4+FoxP3+RORγt+ frequency but virtually no change in CD4+FoxP3−RORγt+ (T helper 17 [TH17]) cells (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 1E). The increased frequency of Tregs in the colonic LP (Figure 1E) persisted for 12 days after treatment, at which time Treg levels in the spleen and LNs were no longer elevated (Figure 1F).15

Recipient Tregs can persist after conditioning (8.5 and 11 Gy) as shown in (supplemental Figure 2A-B) and also after transplantation.35,36,38,51 Five days after TBI (8.5 Gy), Tregs were assessed in BALB/c mice using several protocols of expansion with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD (supplemental Figure 2C-F), among which protocol C resulted in the greatest percentage and numbers of Tregs in the PB, spleen, LP, and liver such that it was used in all subsequent experiments (Figure 1G-I,L-M). Notably, neither CD4 T conventional nor TH17 total cell numbers were significantly altered after Treg expansion using protocol C (Figure 1J-K).

Recipient TNFRSF25 and CD25 receptor stimulation before HSCT induces expansion of resident Tregs and a functionally suppressive milieu in GVHD target tissues

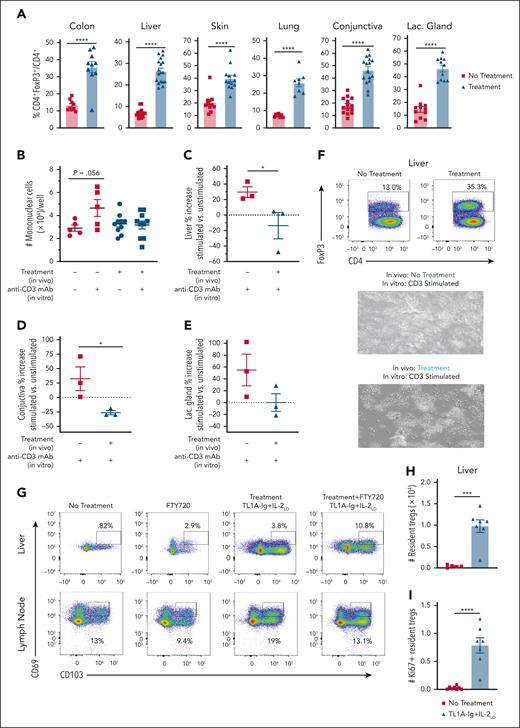

Following stimulation with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD, there was a marked expansion of Tregs (Figure 2A) and particularly the Helios+ Treg population (supplemental Figure 3A-B) was increased in multiple GVHD target tissues, including the skin, liver, lung, and ocular tissue compared with in untreated mice.

Recipient TNFRSF25 and CD25 receptor stimulation before HSCT induces expansion of TR Tregs and a functionally suppressive environment in GVHD target tissues. (A-F) Assessment of GVHD target tissues of recipient BALB/c mice either untreated or treated with protocol C (TL1A-Ig+IL-2) and analyzed 8 days after initiation of treatment (day 0 of BMT). (A) Treg frequencies in nonhematopoietic tissue compartments, that is, the colon, liver, skin, lung, and ocular adnexa (conjunctiva and lacrimal gland), are shown. All GVHD target tissues show significant Treg expansion. (B-E) Measurement of suppressive capabilities of Treg cells isolated from GVHD target tissues on day 0, assessing in vitro proliferation using anti-CD3 mAb. (B) Cell number of colon LP cultures were counted at hour 72 from protocol C–treated and untreated mice. Untreated mice showed higher cell counts than protocol C–treated mice after in vitro anti-CD3 stimulation. (C-E) In vitro studies assessing the liver and the ocular adnexa. Each point represents 1 experiment, and each experiment had a minimum of 3 replicate wells for each group. On day 0, liver CD4+ T cells were enriched via EasySep beads and then plated with anti-CD3 mAb to induce proliferation. (C) Percent increase of enriched liver mononuclear cells at hour 120 shows no net proliferation in cell counts when mice were treated with protocol C. (D) Percent increase of total conjunctiva mononuclear cells at hour 120 if no treatment was given. (E) Percent increase of total lacrimal gland cells at hour 120 if no TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment was given. (F) Representative flow plots depicting the initial frequency of FoxP3+ Tregs at the start of the cultures, and below representative images of well health at hour 120 between in vivo treated or untreated, respectively. (G-I) The S1PR modulator, FTY720, was used to delineate whether the TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–expanded Tregs traffic from hematopoietic sites or proliferate in nonhematopoietic GVHD target tissues at day 8 after starting treatment (see “Methods”). (G) Gating strategy for resident FoxP3+ Tregs (CD69+CD103+) from the liver (upper) and cervical LNs (lower panel). (H) Absolute numbers of liver-resident (CD69+CD103+) Tregs are significantly increased after TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment. (I) Most Tregs highly express the proliferation marker, Ki-67, indicating robust expansion of TR Tregs. Data represent the mean ± SEM, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels.

Recipient TNFRSF25 and CD25 receptor stimulation before HSCT induces expansion of TR Tregs and a functionally suppressive environment in GVHD target tissues. (A-F) Assessment of GVHD target tissues of recipient BALB/c mice either untreated or treated with protocol C (TL1A-Ig+IL-2) and analyzed 8 days after initiation of treatment (day 0 of BMT). (A) Treg frequencies in nonhematopoietic tissue compartments, that is, the colon, liver, skin, lung, and ocular adnexa (conjunctiva and lacrimal gland), are shown. All GVHD target tissues show significant Treg expansion. (B-E) Measurement of suppressive capabilities of Treg cells isolated from GVHD target tissues on day 0, assessing in vitro proliferation using anti-CD3 mAb. (B) Cell number of colon LP cultures were counted at hour 72 from protocol C–treated and untreated mice. Untreated mice showed higher cell counts than protocol C–treated mice after in vitro anti-CD3 stimulation. (C-E) In vitro studies assessing the liver and the ocular adnexa. Each point represents 1 experiment, and each experiment had a minimum of 3 replicate wells for each group. On day 0, liver CD4+ T cells were enriched via EasySep beads and then plated with anti-CD3 mAb to induce proliferation. (C) Percent increase of enriched liver mononuclear cells at hour 120 shows no net proliferation in cell counts when mice were treated with protocol C. (D) Percent increase of total conjunctiva mononuclear cells at hour 120 if no treatment was given. (E) Percent increase of total lacrimal gland cells at hour 120 if no TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment was given. (F) Representative flow plots depicting the initial frequency of FoxP3+ Tregs at the start of the cultures, and below representative images of well health at hour 120 between in vivo treated or untreated, respectively. (G-I) The S1PR modulator, FTY720, was used to delineate whether the TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–expanded Tregs traffic from hematopoietic sites or proliferate in nonhematopoietic GVHD target tissues at day 8 after starting treatment (see “Methods”). (G) Gating strategy for resident FoxP3+ Tregs (CD69+CD103+) from the liver (upper) and cervical LNs (lower panel). (H) Absolute numbers of liver-resident (CD69+CD103+) Tregs are significantly increased after TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment. (I) Most Tregs highly express the proliferation marker, Ki-67, indicating robust expansion of TR Tregs. Data represent the mean ± SEM, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels.

To assess the presence of a suppressive environment in nonhematopoietic tissues, lymphocytes from the colon, liver, and ocular adnexa (conjunctiva and lacrimal gland) from untreated and treated mice were examined in vitro. In contrast to the results obtained from cultures established from mice that did not receive treatment, anti-CD3 stimulation of wells from animals that received treatment did not show proliferation (Figure 2B-F). Therefore, these findings suggest that the tissue milieus reflect a functionally suppressive environment.

To address whether tissue resident (TR) Tregs were targeted by TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD, CD69+CD103+FoxP3+ cells were examined using FTY720 to sequester nonresident T cells to the LNs (supplemental Figure 3C). Notably, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment in combination with FTY720, resulted in a significant increase of Ki-67+ TR Tregs in the liver at the time of euthanasia (Figure 2G-I; supplemental Figure 3D-E). These results support the notion that TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD administration stimulates resident Treg expansion within nonhematopoietic tissues.

Administration of TNFRSF25 and/or CD25 agonists before conditioning results in elevated colonic Treg frequency after transplant accompanied by improved GVHD outcome

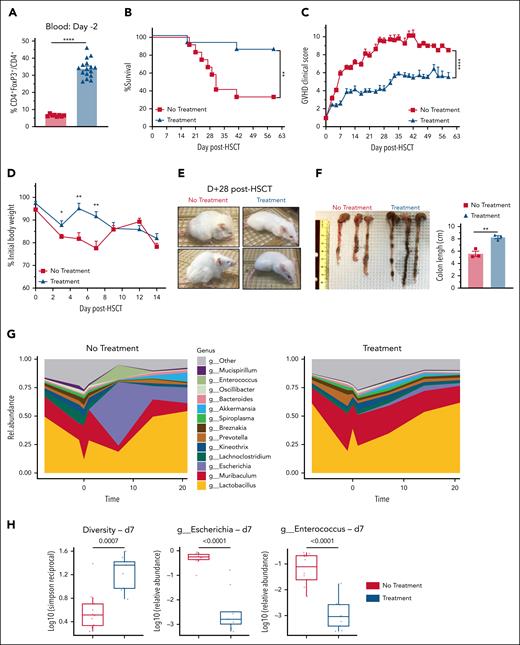

To examine whether pre-HSCT Treg expansion in recipients alters the outcome of aHSCT regarding GVHD, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated mice were transplanted across a complete donor/recipient MHC disparity (supplemental Figure 4A). Pretreated mice exhibited a marked increase (day −2) in the frequency of PB Tregs (Figure 3A). After recipient Treg expansion in BALB/c (H2d) mice before TBI and HSCT with B6 (H2b) TCD BM with/without splenocytes, recipients receiving pretreatment showed increased survival and diminished GVHD clinical scores (Figure 3B-C; supplemental Figure 4B). Initial weight loss early after HSCT was reduced in treated animals, and their overall appearance was clearly improved (Figure 3D-E). Colon integrity determined by fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran leakage assays (supplemental Figure 4C), and colon lengths were greater in treated compared with untreated recipients, 6 weeks after transplant (Figure 3F).

Recipient Treg expansion with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before transplant significantly diminished GVHD severity, promoted colonic microbiome diversity, and improved overall survival. (A-F) BALB/c mice were treated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before TBI. aHSCT was performed using a B6 (donor) → BALB/c (recipient) major MHC-mismatch model. CD45.1 B6 (H2b) TCD BM cell (5.5 × 106) and an adjusted spleen cell number containing 0.55 × 106 T cells were transplanted into BALB/c (H2d) recipients. TBI was 7.25 Gy given on day −1. Presented aHSCT data were pooled from 2 independent experiments representing 16 mice per group. (A) Confirmation of Treg expansion (CD4+FoxP3+/CD4+) in the PB on day −2. (B-F) Panels show survival (n = 8) (B), GVHD clinical score (n = 8) (C), percent weight loss (n = 8) (D), general mouse appearance (E), and colon lengths (F). (B) Overall survival was 38% without recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment vs 89% with recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment. There was a significant difference in GVHD clinical scores over 63 days (C) and less percent weight loss early after aHSCT (D). Representative photographs depict animal appearance at day +28 after aHSCT (E). (F) Colon lengths of mice (n = 6, 3 from each group) at day +42 after aHSCT. (G) Relative abundance of bacterial microbiome over time in untreated and TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated recipients. Mice were assessed at day 0, day +7, day +10, day +14, and day +20 (n = 10). (H) TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated recipients displayed greater microbiome diversity at day +7. Bacterial diversity (Simpson reciprocal) and specific genus-level relative abundance of Escherichia and Enterococcus. Data represent the mean ± SEM, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels.

Recipient Treg expansion with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before transplant significantly diminished GVHD severity, promoted colonic microbiome diversity, and improved overall survival. (A-F) BALB/c mice were treated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before TBI. aHSCT was performed using a B6 (donor) → BALB/c (recipient) major MHC-mismatch model. CD45.1 B6 (H2b) TCD BM cell (5.5 × 106) and an adjusted spleen cell number containing 0.55 × 106 T cells were transplanted into BALB/c (H2d) recipients. TBI was 7.25 Gy given on day −1. Presented aHSCT data were pooled from 2 independent experiments representing 16 mice per group. (A) Confirmation of Treg expansion (CD4+FoxP3+/CD4+) in the PB on day −2. (B-F) Panels show survival (n = 8) (B), GVHD clinical score (n = 8) (C), percent weight loss (n = 8) (D), general mouse appearance (E), and colon lengths (F). (B) Overall survival was 38% without recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment vs 89% with recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment. There was a significant difference in GVHD clinical scores over 63 days (C) and less percent weight loss early after aHSCT (D). Representative photographs depict animal appearance at day +28 after aHSCT (E). (F) Colon lengths of mice (n = 6, 3 from each group) at day +42 after aHSCT. (G) Relative abundance of bacterial microbiome over time in untreated and TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated recipients. Mice were assessed at day 0, day +7, day +10, day +14, and day +20 (n = 10). (H) TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated recipients displayed greater microbiome diversity at day +7. Bacterial diversity (Simpson reciprocal) and specific genus-level relative abundance of Escherichia and Enterococcus. Data represent the mean ± SEM, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels.

The intestinal microbiome has been found to become less heterogeneous in GVHD, thus fecal material was collected and analyzed for bacterial species and relative diversity.52-54 Recipient pretreatment resulted in a more diverse intestinal microbiome after aHSCT compared with untreated BALB/c recipients (Figure 3G-H). Moreover, in the absence of pretreatment, higher levels of pathogenic species (eg, Escherichia and Enterococcus) were identified (Figure 3H). Maintenance of butyrate-producing and obligate-anaerobe microbes, as well as epithelial H2O2 production, were observed in pretreated compared with untreated recipients (supplemental Figure 4D-F), consistent with a more physiologic GI environment.

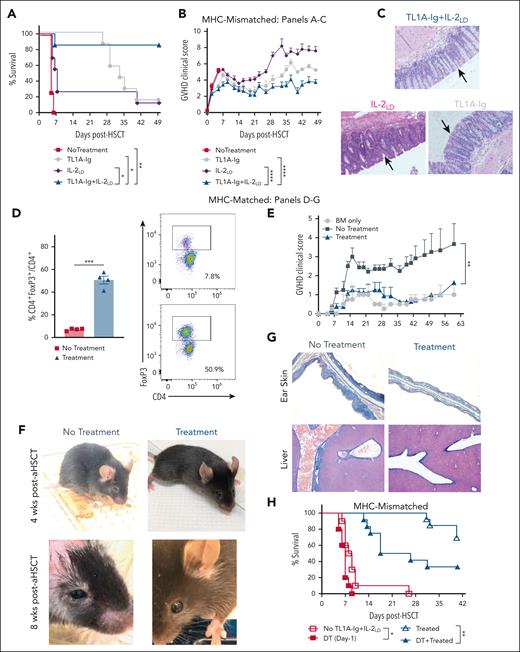

To evaluate the effect on GVHD outcomes of individual TNFRSF25 or CD25 compared with combinatorial stimulation, mice were administered only TL1A-Ig, only IL-2LD, or the combination thereof to augment the Treg compartment (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 5A-C). After aHSCT, outcomes assessed by overall survival and GVHD clinical scores indicated that pretreatment with IL-2LD alone had minimal Treg effects whereas pretreatments that included TL1A-Ig resulted in reduced colonic cellular infiltrates and significant improvement in survival and clinical scores compared with untreated recipients (Figure 4A-C).

Combinatorial vs individual TL1A-Ig and IL-2 treatment before major and minor MHC-mismatched aHSCT. (A-C) Evaluation of recipients after individual TNFRSF25 or high-affinity IL-2 receptor stimulation compared with combined stimulation before conditioning and aHSCT. Mice were administered TL1A-Ig only, IL-2LD only, or TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD (see supplemental Figure 4A for details). aHSCT was performed using a B6→BALB/c donor/recipient mouse model. B6-FoxP3RFP (H2b) TCD BM (5.5 × 106) cells and an adjusted spleen cell number containing 6.5 × 105 T cells were transplanted into BALB/c (H2d) recipients after TBI conditioning (7.75 Gy) on day-1. (A) Overall survival (n = 7), (B) GVHD clinical score (n = 7), and (C) representative colon histological images of tissue harvested at day +56. Arrows indicate differences in villi structure, more normal appearance in TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD vs monotherapy. Combinatorial pretreatment resulted in the best outcomes, with fewer lymphocytic infiltrates in the colonic tissue. (D-G) The combinatorial treatment was examined in a second (low lethality) aHSCT model. MHC-matched, minor antigen–mismatched C3H.SW (H2b) TCD BM (7 × 106) cells and 2 × 106 CD8+ T cells were transplanted into B6 (H2b) recipients after TBI conditioning (10.5 Gy) on day 0. (D) At day −2, assessing Treg frequencies showed significant CD4+FoxP3+/CD4+ expansion with pretreatment. (E) GVHD clinical scores were less severe in pretreated recipients (n = 4-8). (F) Representative images of mice show appearances at 4 and 8 weeks after aHSCT. Pretreated recipients exhibited less skin and ocular GVHD involvement. (G) Collagen deposition (Masson trichrome stain, blue) in the skin of mice 8 weeks after aHSCT. In treated recipients, note the thin epidermis, scant dermis collagen staining, and the absence of inflammatory cells compared with untreated recipients exhibiting a thickened epidermis, extensive collagen deposition in the dermis, and a modest infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells (original magnification ×10). Heightened collagen and hepatic periportal infiltrates were detected in untreated MHC-matched recipients. (H) Treg depletion immediately before transplant reduces but does not abolish GVHD. BALB/c DT receptor mice were untreated or pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before transplant with B6 TCD BM spleen cells. DT (1 μg IP) was administered on day −1 before TBI. Depleting resident Tregs reduced overall survival in pretreated as well as in untreated recipients (n = 5-7). Wks, weeks.

Combinatorial vs individual TL1A-Ig and IL-2 treatment before major and minor MHC-mismatched aHSCT. (A-C) Evaluation of recipients after individual TNFRSF25 or high-affinity IL-2 receptor stimulation compared with combined stimulation before conditioning and aHSCT. Mice were administered TL1A-Ig only, IL-2LD only, or TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD (see supplemental Figure 4A for details). aHSCT was performed using a B6→BALB/c donor/recipient mouse model. B6-FoxP3RFP (H2b) TCD BM (5.5 × 106) cells and an adjusted spleen cell number containing 6.5 × 105 T cells were transplanted into BALB/c (H2d) recipients after TBI conditioning (7.75 Gy) on day-1. (A) Overall survival (n = 7), (B) GVHD clinical score (n = 7), and (C) representative colon histological images of tissue harvested at day +56. Arrows indicate differences in villi structure, more normal appearance in TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD vs monotherapy. Combinatorial pretreatment resulted in the best outcomes, with fewer lymphocytic infiltrates in the colonic tissue. (D-G) The combinatorial treatment was examined in a second (low lethality) aHSCT model. MHC-matched, minor antigen–mismatched C3H.SW (H2b) TCD BM (7 × 106) cells and 2 × 106 CD8+ T cells were transplanted into B6 (H2b) recipients after TBI conditioning (10.5 Gy) on day 0. (D) At day −2, assessing Treg frequencies showed significant CD4+FoxP3+/CD4+ expansion with pretreatment. (E) GVHD clinical scores were less severe in pretreated recipients (n = 4-8). (F) Representative images of mice show appearances at 4 and 8 weeks after aHSCT. Pretreated recipients exhibited less skin and ocular GVHD involvement. (G) Collagen deposition (Masson trichrome stain, blue) in the skin of mice 8 weeks after aHSCT. In treated recipients, note the thin epidermis, scant dermis collagen staining, and the absence of inflammatory cells compared with untreated recipients exhibiting a thickened epidermis, extensive collagen deposition in the dermis, and a modest infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells (original magnification ×10). Heightened collagen and hepatic periportal infiltrates were detected in untreated MHC-matched recipients. (H) Treg depletion immediately before transplant reduces but does not abolish GVHD. BALB/c DT receptor mice were untreated or pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before transplant with B6 TCD BM spleen cells. DT (1 μg IP) was administered on day −1 before TBI. Depleting resident Tregs reduced overall survival in pretreated as well as in untreated recipients (n = 5-7). Wks, weeks.

Because combinatorial pretreatment resulted in the greatest protection from GVHD, the protocol was examined in a second (low lethality) aHSCT model. MHC-matched, minor antigen mismatched C3H.SW (H2b) BM + T cells were transplanted into B6 (H2b) recipients. As anticipated, Treg levels were markedly expanded with administration of TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before HSCT (Figure 4D). Clinical scores were significantly diminished in treated recipients (Figure 4E). Representative photographs (Figure 4F) 4 and 8 weeks after transplant illustrate the improved appearance of treated mice accompanied by less histopathologic involvement in the skin and liver and less eye involvement (Figure 4F-G).

To assess whether the depletion of expanded Tregs affected GVHD outcomes, FoxP3-diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor (DTR; BALB/c-FoxP3DTR–eGFP) mice were pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD and administered DT immediately before TBI (supplemental Figure 5D-F). As anticipated, animals pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD exhibited significantly greater overall survival than untreated recipients. Removal of Tregs considerably decreased the percent survival in TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treated animals, providing evidence that Tregs are important in the amelioration of GVHD (Figure 4H). Consistent with the importance of Tregs in GVHD suppression, removal of these cells in vitro resulted in elevated T-cell responses upon anti-CD3 mAb stimulation (supplemental Figure 5G). This activity was TNFRSF25 dependent, because TNFRSF25 receptor–knockout mice did not exhibit significantly increased Tregs in vivo after TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment or suppressive activity in vitro (Figure 5A-B). To definitively demonstrate the requirement for Treg TNFRSF25 expression and signaling via TL1A-Ig for activation and expansion, B6-TNFRSF25−/− spleen and LN cells were adoptively transferred into B6-TNFRSF25+/+ mice. In contrast to TNFRSF25+/+ wild-type Tregs, TNFRSF25−/− knockout Tregs did not expand as well, and did not express Ki-67 in response to TL1A-Ig. As anticipated, a small increase in TNFRSF25−/− Tregs was detected after IL-2LD administration (Figure 5C-D).

TNFRSF25 signaling on CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs is critical for their activation and expansion. (A) TNFRSF25 expression is required for TL1A-Ig–induced Treg expansion in vivo. Frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs in the spleens at day 0 from their respective mice (BALB/c TNFRSF25+/+, WT and BALB/c TNFRSF25−/−, KO) with/without TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. (B) Loss of suppression in the absence of the expression of TNFRSF25 followed by TL1A-Ig in vivo stimulation. Number of total splenocytes at 80 hours after culture by their respective mice, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment, and anti-CD3 mAb (1 μg). (C-D) Spleen and LN cells (1 × 107) from B6-CD45.2 TNFRSF25 KO mice were transferred IV into B6-CD45.1 WT mice. After 24 hours, treatment with TL1A-Ig with/without IL-2LD was initiated. Peripheral and mesenteric LNs were harvested on day 6. Single-cell suspensions were prepared and Treg expansion was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) In contrast to TNFRSF25+/+ Tregs, TNFRSF25−/− (KO) Tregs do not respond to TL1A-Ig treatment in vivo. TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment induced a small increase in TNFRSF25−/− Tregs. (D) In contrast to TNFRSF25+/+ Tregs, TNFRSF25−/− (KO) Tregs do not express Ki-67 in response to TL1A-Ig treatment in vivo. However, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment induced a small increase in Ki-67+ TNFRSF25−/− Tregs. KO, knockout.

TNFRSF25 signaling on CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs is critical for their activation and expansion. (A) TNFRSF25 expression is required for TL1A-Ig–induced Treg expansion in vivo. Frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs in the spleens at day 0 from their respective mice (BALB/c TNFRSF25+/+, WT and BALB/c TNFRSF25−/−, KO) with/without TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. (B) Loss of suppression in the absence of the expression of TNFRSF25 followed by TL1A-Ig in vivo stimulation. Number of total splenocytes at 80 hours after culture by their respective mice, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment, and anti-CD3 mAb (1 μg). (C-D) Spleen and LN cells (1 × 107) from B6-CD45.2 TNFRSF25 KO mice were transferred IV into B6-CD45.1 WT mice. After 24 hours, treatment with TL1A-Ig with/without IL-2LD was initiated. Peripheral and mesenteric LNs were harvested on day 6. Single-cell suspensions were prepared and Treg expansion was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) In contrast to TNFRSF25+/+ Tregs, TNFRSF25−/− (KO) Tregs do not respond to TL1A-Ig treatment in vivo. TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment induced a small increase in TNFRSF25−/− Tregs. (D) In contrast to TNFRSF25+/+ Tregs, TNFRSF25−/− (KO) Tregs do not express Ki-67 in response to TL1A-Ig treatment in vivo. However, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment induced a small increase in Ki-67+ TNFRSF25−/− Tregs. KO, knockout.

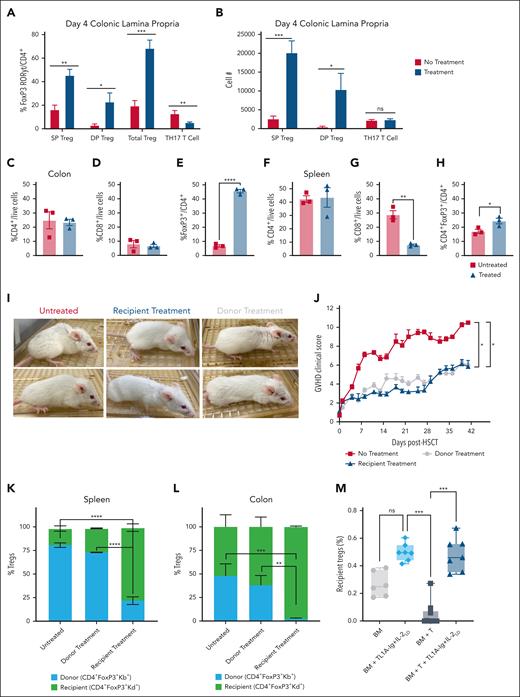

Administration of TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before conditioning and transplant resulted in a strong preponderance of recipient Tregs in the colonic LP and spleen after HSCT

Administration of TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD into normal, nontransplanted animals resulted in a strong increase in Treg levels in the colonic LP, which persisted for 12 days (Figure 1E). To investigate whether the frequency was also elevated early after conditioning and transplant, Treg levels were examined in the colons of TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated and untreated BALB/c recipients, 4 days after HSCT with MHC-mismatched donor B6 cells (Figure 6A-H; supplemental Figure 6). Assessment of the colonic LP revealed that CD4+FoxP3+Treg frequency was significantly elevated in this compartment as initially observed in the absence of a transplant (Figure 1D-F). Both single- (FoxP3+RORγt−) and double-positive (FoxP3+RORγt+) Treg populations exhibited elevated frequency and numbers 4 days after transplant (Figure 6A-B). In contrast, frequency of TH17 (CD4+FoxP3-RORγt+), total CD4, and CD8 cells did not exhibit any increase in these Treg-expanded animals (Figure 6A,C-D). The Treg frequency was also elevated in the spleen 4 days after HSCT; however, the relative increase compared with the colon was lower, whereas the CD8 frequency was significantly reduced (Figure 6F-H; supplemental Figure 6A). To corroborate selective Treg increase and persistence at this time in the colon, pretreatment with an anti-TNFRSF25 agonistic mAb (mPTX35) and IL-2LD was administered to BALB/c mice, before B6 transplant (supplemental Figure 7A-B). As anticipated, a significant increase in single- and double-positive Tregs was observed. Notably, Treg elevation was also present 10 days after HSCT in treated animals (Figure 6M). These day-4 and -10 findings were further corroborated examining foxp3 gene expression, which found a relative RNA increase in the colons of treated vs untreated animals (supplemental Figure 6B).

Donor- and recipient-expanded Tregs significantly diminished GVHD severity. (A-H) Recipient BALB/c mice were pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. An aHSCT (B6 → BALB/c) was performed on day 0 (n = 3 mice per group) after conditioning on day −1. TR colonic LP lymphocytes were assessed at day +4 (A) and +10 (M) after aHSCT. The frequencies (A) and absolute numbers (B) of FoxP3+RORγt−/CD4+ T cells, FoxP3+RORγt+/CD4+ T cells, total Tregs, and TH17/CD4+ T cells at day +4 are shown. The frequencies of CD4+, CD8+, and FoxP3+/CD4+ T cells from colon LP (C-E) and spleen cells (F-H) are shown. (I-J) Pretreated BALB/c recipients of B6 aHSCT exhibited improved appearance (day +28 after aHSCT) and significantly improved clinical scores, depicting reduced GVHD scores in both donor and recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated groups compared with the untreated group; n = 8 for panel J. (K-L) TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated recipients demonstrated a preponderance of recipient Tregs in the colon and spleen. Donor (Kb+) and recipient (Kd+) Treg frequencies on day +5 after aHSCT (B6 → BALB/c) in the spleen (K) and colon (L) were analyzed. TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD pretreatment (n = 8 mice per group) resulted in a majority and almost exclusively Tregs of recipient origin in both the spleen and colon, respectively. Notably, at day +5 after aHSCT, in contrast to the spleen (K), recipient Tregs in the colon (L) still represented most of the Treg population (L) after transplant with Treg-expanded donor cells; n = 5 for panels K-L. (M) The frequencies of CD4+FoxP3+/CD4+ T cells, at day +10 are shown. Data represent combined data from 3 independent B6→BALB/c transplant experiments (n = 6-9 per group). Data represent the mean ± SEM, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels. DP, double positive (FoxP3+RORγt+); SP, single positive (FoxP3+RORγt-).

Donor- and recipient-expanded Tregs significantly diminished GVHD severity. (A-H) Recipient BALB/c mice were pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. An aHSCT (B6 → BALB/c) was performed on day 0 (n = 3 mice per group) after conditioning on day −1. TR colonic LP lymphocytes were assessed at day +4 (A) and +10 (M) after aHSCT. The frequencies (A) and absolute numbers (B) of FoxP3+RORγt−/CD4+ T cells, FoxP3+RORγt+/CD4+ T cells, total Tregs, and TH17/CD4+ T cells at day +4 are shown. The frequencies of CD4+, CD8+, and FoxP3+/CD4+ T cells from colon LP (C-E) and spleen cells (F-H) are shown. (I-J) Pretreated BALB/c recipients of B6 aHSCT exhibited improved appearance (day +28 after aHSCT) and significantly improved clinical scores, depicting reduced GVHD scores in both donor and recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated groups compared with the untreated group; n = 8 for panel J. (K-L) TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated recipients demonstrated a preponderance of recipient Tregs in the colon and spleen. Donor (Kb+) and recipient (Kd+) Treg frequencies on day +5 after aHSCT (B6 → BALB/c) in the spleen (K) and colon (L) were analyzed. TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD pretreatment (n = 8 mice per group) resulted in a majority and almost exclusively Tregs of recipient origin in both the spleen and colon, respectively. Notably, at day +5 after aHSCT, in contrast to the spleen (K), recipient Tregs in the colon (L) still represented most of the Treg population (L) after transplant with Treg-expanded donor cells; n = 5 for panels K-L. (M) The frequencies of CD4+FoxP3+/CD4+ T cells, at day +10 are shown. Data represent combined data from 3 independent B6→BALB/c transplant experiments (n = 6-9 per group). Data represent the mean ± SEM, with ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 defining significance levels. DP, double positive (FoxP3+RORγt+); SP, single positive (FoxP3+RORγt-).

The elevated frequency of Tregs in recipients after transplant could be comprised of both donor and host Tregs. A transplant was performed with recipients either untreated, transplanted with cells from Treg-expanded donors, or pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD (Figure 6I-J).15 GVHD was markedly ameliorated in the latter 2 groups (supplemental Figure 7C). In both, untreated recipients and recipients receiving Treg expanded donor spleen cells, the preponderance of Tregs in the spleen were donor derived at 4 to 5 days after aHSCT (Figure 6K). In contrast, recipient pretreatment established a marked predominance of host Tregs (Figure 6K-L). Notably, recipient Tregs comprised ∼50% in the colon of untreated or mice receiving transplants from Treg-expanded donors at this time (Figure 6L). Strikingly, pretreatment resulted in almost complete recipient Treg presence (Figure 6K-L). Therefore, a preponderance of recipient Tregs was associated with improved transplant outcomes, correlated with diminished proliferation of donor Tconv CD4 cells (supplemental Figure 7D-E).

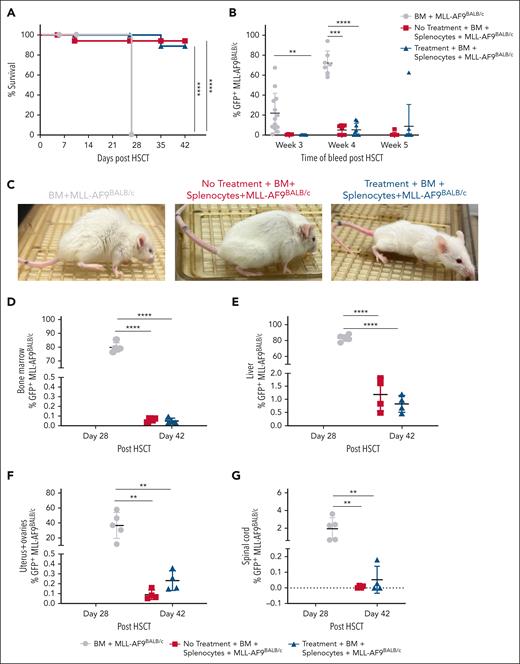

The antileukemia response is maintained in TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated recipients after aHSCT with MLL-AF9 leukemia cells

Groups of BALB/c pretreated recipients received transplantation with B6 TCD-BM with/without splenocytes and BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP acute myeloid leukemia cells to determine whether GVL responses were maintained in TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated mice. Recipients of B6 BM only + MLL-AF9GFP cells all died by 4 weeks after aHSCT because of tumor outgrowth (Figure 7A-B). Untreated recipients transplanted with B6 TCD BM + splenic T cells survived longer as a consequence of the GVL effect (Figure 7A-B). As anticipated, TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–treated recipients showed diminished clinical manifestations of GVHD 4 weeks after aHSCT (Figure 7C). We identified MLL-AF9GPF cells in the BM, liver, reproductive organs (uterus and ovaries), and spinal cord of recipients transplanted with B6 BM alone beginning ∼4 weeks after aHSCT; however, tumor cells were not detected in pretreated recipients receiving the identical transplant with TCD BM + splenic T cells at week 6 after aHSCT (Figure 7D-G). These findings indicate that pretreatment of recipients using TNFRSF25 and CD25 agonists did not impair their ability to mount antileukemia cell responses after aHSCT.

Recipient mice pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before aHSCT enable GVL responses concomitant with GVHD amelioration. B6 (donor) → BALB/c (recipient) aHSCT with and without recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD pretreatment was performed. All groups received 5 × 103 BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP cells (IV) at the time of aHSCT, (n = 9-13 mice per group). (A) Overall survival. No animals survived in the BM-only group vs >85% for the (BM + T cells) and (BM + T cells with recipient treatment) groups (n = 5). (B) BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP cell frequency in the PB at 3, 4, and 5 weeks after aHSCT. Treg expansion in the recipient group enabled a GVL response against BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP cells that was as effective as the response in untreated recipients (BM + T cells) denoted by minimal detection of GFP expression. (C) Representative photographs of mice from each group at 4 weeks after aHSCT. (D-G) BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP frequency in hematopoietic compartments, that is, the BM (D); and nonhematopoietic compartments, that is, the liver (E), uterus and ovaries (F), and spinal cord (G), at days 28 and 42 after aHSCT.

Recipient mice pretreated with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD before aHSCT enable GVL responses concomitant with GVHD amelioration. B6 (donor) → BALB/c (recipient) aHSCT with and without recipient TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD pretreatment was performed. All groups received 5 × 103 BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP cells (IV) at the time of aHSCT, (n = 9-13 mice per group). (A) Overall survival. No animals survived in the BM-only group vs >85% for the (BM + T cells) and (BM + T cells with recipient treatment) groups (n = 5). (B) BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP cell frequency in the PB at 3, 4, and 5 weeks after aHSCT. Treg expansion in the recipient group enabled a GVL response against BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP cells that was as effective as the response in untreated recipients (BM + T cells) denoted by minimal detection of GFP expression. (C) Representative photographs of mice from each group at 4 weeks after aHSCT. (D-G) BALB/c-MLL-AF9GFP frequency in hematopoietic compartments, that is, the BM (D); and nonhematopoietic compartments, that is, the liver (E), uterus and ovaries (F), and spinal cord (G), at days 28 and 42 after aHSCT.

Discussion

Tregs can alter immune responses under physiologic conditions, and their application as cellular therapy to diminish those responses in transplantation and autoimmune diseases continues to show promise.55-61 Expansion of Tregs using IL-2 muteins and other reagents to increase this compartment in vivo continues to advance.56,62-64 Our laboratory has developed strategies to augment Tregs in vivo by targeting the TNFRSF25 receptor alone and together with IL-2LD.15,42,55,65 Although most Treg-expansion approaches in HSCT have focused on the use of donor-derived Tregs, this investigation reports, to our knowledge, for the first time a translatable strategy to expand Tregs in recipients before transplant. Results demonstrated that elevation in CD4+FoxP3+ Treg frequency and numbers after transplant was associated with diminished GVHD and improved outcomes post-aHSCT across major and minor histocompatibility disparities while maintaining GVL.18,19,26,66-70 Current practice uses calcineurin inhibitors and other immunosuppressives for extended time periods after HSCT in attempt to prevent GVHD. In contrast, the strategy described in this study is implemented before transplant over a brief time period.

TNFRSF25 is a costimulatory molecule upregulated on CD4+ Tconv and CD8+ T cells after activation.71,72 In contrast, this molecule is constitutively expressed on Tregs and in wild-type untransplanted mice, and we reported that its signaling can rapidly expand these cells after administering an agonistic fusion protein (TL1A-Ig) or mAb (4C12).15,42,55,65 Importantly, studies here demonstrated the requirement for TNFRSF25 signaling by TL1A-Ig on Tregs for this expansion. We previously identified a 6-day in vivo protocol resulting in marked Treg expansion in multiple compartments, including the blood, LNs, spleen, and colon but not in the BM.15 A decrease in Treg frequency (as well as dysfunction) in the PB has been reported in patients with chronic GVHD.16,73-75 This study, using spatial biology, corroborated this observation and also identified a deficit in Treg levels and function in the colon of mice with GVHD. We hypothesized that expanding the Treg compartment in the recipient before transplant may prevent a Treg deficit. Attempts to expand the compartment immediately after transplant with mAbs targeting TNFRSF25 exacerbated GVHD because of stimulation of activated donor T cells.76 We therefore applied our Treg expansion protocol immediately before HSCT. The TL1A-Ig fusion protein and not mAb was selected because of its short half-life to avoid potential stimulation of donor alloreactive T cells and resulted in significantly improved transplant outcomes.42

TR Tregs with distinct transcriptional and epigenetic programs reside in nonlymphoid compartments including important GVHD target tissues.77 TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD administration was shown to significantly elevate Tregs in the skin, liver, colon, eye, and lung. Notably, after blocking egress of Tregs from the LNs with FTY720, we found that CD103+CD69+ TR Tregs were markedly increased in the liver, indicating their expansion in the target tissues. Importantly, we detected a preponderance of recipient Tregs in multiple compartments during the first week posttransplant after pretransplant expansion with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD. Because we found that in vitro stimulated T-cell responses from tissues were suppressed after Treg expansion, we posit that pretreatment promoted a locally suppressive environment persisting early after transplant, thereby reducing GVHD. Consistent with this interpretation, deletion of recipient Tregs via DT injection after expansion 1 day before aHSCT resulted in significantly reduced but not abolished protection. Therefore, we speculate that other populations could also be contributing to the observed effect, and we aim to investigate this possibility in our future studies. Thus, although TL1A-Ig alone elevated Tregs in nonhematopoietic tissues comparable with combination treatment, GVHD outcomes were best after TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD treatment.

Recent reports in transplant patients have shown that recipient T cells, including Tregs, although absent in the blood, were present in GVHD target tissues >1 year after aHSCT.36,37 These findings indicate that such cells survived conditioning and, moreover, were functionally competent and able to proliferate.36,37 Tregs are reportedly more resistant to radiotherapy and cyclophosphamide than conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which may contribute to their relative enrichment post-aHSCT.30,35,78 Recipient Tregs comprised the predominant component of the CD4+FoxP3+ compartment in the LNs 5 weeks after autologous HSCT in mice, and these persistent Tregs were found to mediate suppressive function.38,51 Notably, recipient Tregs were present after TBI, cyclophosphamide, and busulfan conditioning protocols.38 Consistent with these observations, we found elevated levels of recipient Tregs in multiple tissues after their expansion before transplant. Helios has been reported to regulate and stabilize Foxp3 expression as well as Treg-suppressive function and survival, as Helios deficiency results in the loss of Treg lineage in inflammatory conditions.79-84 Notably, Helios’ expression was substantially increased in TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–expanded Tregs in multiple tissues at the time of conditioning and transplant.

We wanted to address whether our treatment protocol prevented dysregulation of the GI microbiome. Perturbations of the GI microbiome can cause immune dysregulation after aHSCT, and major alterations including reduced diversity have been identified in the colon in patients with GVHD.52-54,85-89 Pretreatment with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD maintained bacterial species diversity and promoted butyrate-producing species while diminishing pathogenic bacterial overgrowth. These modifications are of note as butyrate plays a key role in the promotion of Treg differentiation and stability, improves suppressive function, and enhances metabolic support and expansion in the gut.90-92 Hypoxia in the colon regulates the colonization of bacterial species, and in pretreated mice, there was a higher ratio of obligate to facultative anaerobic species, consistent with a more homeostatic hypoxia status. Dual oxidase 2 signaling in the gut is critical for H2O2 production, important for microbial defense, and involved in regulating epithelial cell proliferation and repair.93-96 Commensal bacteria induces Dual oxidase 2 expression under physiologic conditions whereas dysbiosis can lead to its dysregulation, leading to epithelial injury and impairing epithelial repair mechanisms.93-95,97,98 Although transplant conditioning here was associated with transient bacterial dysregulation and elevated H2O2 levels early after aHSCT, animals with GVHD exhibited sustained, elevated levels of colonic H2O2 at least 3 weeks post-aHSCT. In contrast, H2O2 production in pretreated recipients of BM + T cells was comparable with levels in recipients of BM alone. Therefore, we conclude that TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD administration promoted epithelial cell integrity and preservation of indigenous microbiota, and, overall, support the effectiveness of our pretreatment protocol with regard to GVHD prophylaxis.

Maintaining GVL responses while ameliorating GVHD despite Treg expansion is important for translational applicability. MLL-AF9GFP leukemia cells were transplanted together with BM with/without splenocytes to assess antitumor activity. TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–pretreated animals mediated GVL responses in the presence of elevated Treg levels as indicated by absence of leukemia cells in multiple compartments comparable with nonpretreated recipients of BM with/without splenocyte transplants. We have reported previously that TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD does not increase Treg levels in the marrow, a key site of MLL-AF9 expansion.15 Pretreatment elevated Treg levels in GVHD target tissues, that is, the liver, skin, and eye. This differential tissue Treg expansion together with potential antitumor antigen-specific responses may explain why, as others have reported, Treg suppression of GVHD (alloantigen-specific T cells) here did not abolish antileukemia cell responses.15,19

Tregs have been recognized as a promising approach to regulate allogeneic HSCT as evidenced by numerous strategies being examined. Although obtaining sufficient numbers of Tregs has been a challenge, adoptive transfer of freshly isolated Tregs can be useful in transplants and autoimmune disease.99 Ex vivo–expanded natural Tregs and in vitro–generated induced Tregs have also been applied with promising results.100-102 Additionally, chimeric antigen receptor Tregs have been produced recently and may lead to future therapeutic options.103

In summary, the studies here have manipulated the recipient Treg compartment with TL1A-Ig+IL-2LD–expanded Treg cells in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues, including the colon, which is central to the induction of GVHD.55,104 As a result of increasing their numbers before aHSCT followed by persistence after aHSCT, this leads to elevation of recipient Tregs in GVHD target tissues several weeks after transplant, supporting the notion that the observed Treg deficit in GVHD can be reduced using this approach. In contrast to the infusion of donor Tregs, this pretreatment strategy that we have developed results in the presence of immune-suppressive target tissue environments in the recipient before donor alloreactive T-cell infusion. We posit strategies that circumvent the need of producing large numbers of Tregs ex vivo by manipulating this compartment in vivo, may also provide an effective therapeutic approach for GVHD prophylaxis while maintaining GVL. Our long-term objective is to investigate application of our treatment with clinically relevant GVHD therapy including post-transplant cyclophosphamide, rapamycin, and JAK inhibitors, and to directly assess efficacy of human reagents to stimulate human regulatory populations in vivo using humanized mouse models toward translating our findings to clinical HSCT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sylvester Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Core for their help and support. Special acknowledgement is extended to Core staff members, specifically, Patricia Guevara, Shannon Saigh, Brit Chapman, and Eric Weider for their help with terraFlow and all flow cytometric analysis. The researchers acknowledge Trent Wang, Eric Weider, and Cara Benjamin for their help in securing patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells for flow cytometric analysis. The authors recognize the help and support of Paolo Serafini and his laboratory in performing CODEX analysis using the Akoya equipment and system. They extend their appreciation to Gina Adams for her invaluable technical support throughout this study; and Casey O. Lightbourn, Jaret Fensterstock, and Alex Tudor for their work in the laboratory. The researchers are indebted to Nurcin Liman (National Cancer Institute [NCI], National Institutes of Health [NIH]) for her coordination and efforts in the TNFRSF25(DR3)-knockout experiments. The authors also thank Sophie Paczesny (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) for graciously providing the BALB/c MLL-AF9GFP+ cells used in the graft-versus-leukemia studies and Heat Biologics, Inc for the mPTX-35 antibody. Appreciation is extended to Kathryn LePorte for guidance with the FTY720 experiments.

R.B.L. was supported by funding from the Sylvester Cancer Center and the Applebaum Foundation. R.B.L. and V.L.P. were supported by grants from the National Eye Institute (NEI), NIH (R01EY024484, R01EY030283). S.N.C. was supported by the New Investigator Award: Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Society. M.G. was supported by an NEI, NIH diversity supplement (3R01EY030283-03S1). B.J.P. was supported by funding from the Micah Batchelor Fellowship Award for Excellence in Children’s Health Research, 2019. M.T.A. was supported by a VA Merit Review award I01BX001245, and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH (R01DK099076), the Micky & Madeleine Arison Family Foundation Crohn’s & Colitis Discovery Laboratory, and the Martin Kalser Endowed Chair (M.T.A.). M.R.M.v.d.B. is supported, in part, by the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Internal Diversity Enhancement Award; NCI, NIH award numbers R01-CA228358, R01-CA228308, and P30 CA008748 MSK Cancer Center Core Grant and P01-CA023766; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), NIH award numbers R01-HL123340, R01-HL147584, and K08HL143189; National Institute on Aging (NIA), NIH award number P01-AG052359; Starr Cancer Consortium; and Tri Institutional Stem Cell Initiative. Additional funding was received from the Lymphoma Foundation, The Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program, Cycle for Survival, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Cancer Systems Immunology Pilot Grant, Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program, the Society for MSK, the Staff Foundation, the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, the MSKCC Leukemia SPORE Career Enhancement Program, and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. G.R.H. is supported by NCI, NIH grants P01 CA018029, P01 CA078902, and R21 CA286216, NHLBI, NIH grant R01 HL148164, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH grant R01 AI175535.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: D.M., S.N.C., B.J.P., D.W., H.B., S.M., A.K., S.K., M.B.d.S., H.H., S.G.L., and M.G. performed research; M.R.M.v.d.B., J.-H.P., M.T.A., G.R.H., V.L.P., and R.B.L. provided reagents and support; D.M., S.N.C., B.J.P., H.B., M.B.d.S., H.H., and R.B.L. designed research and analyzed data; D.M., S.N.C., B.J.P., D.W., and R.B.L. wrote the manuscript; and H.B., M.B.d.S., H.H., J.-H.P. and G.R.H. critiqued the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.W. is an uncompensated consultant and equity holder in Eniale Immunotherapeutics, Inc. M.T.A. has served as a consultant for, or on the advisory board of, AbbVie Inc, Amgen Inc, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celsius Therapeutics, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences Inc, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer Pharmaceutical; and has been a teacher, lecturer, or speaker at Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. M.R.M.v.d.B. has received research support and stock options from Seres Therapeutics and stock options from Notch Therapeutics and Pluto Therapeutics; has received royalties from Wolters Kluwer; has consulted for, received honoraria from, or participated in advisory boards for, Seres Therapeutics, Vor Biopharma, Rheos Medicines, Frazier Healthcare Partners, Nektar Therapeutics, Notch Therapeutics, Ceramedix, Lygenesis, Pluto Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Da Volterra, Thymofox, Garuda, Novartis (spouse), Synthekine (spouse), BeiGene, (spouse), and Kite (spouse); has intellectual property licensing with Seres Therapeutics and Juno Therapeutics; and holds a fiduciary role on the Foundation Board of Deutsche Knochenmarkspenderdatei (a nonprofit organization). MSKCC has institutional financial interests relative to Seres Therapeutics. G.R.H. has consulted for Generon Corporation, NapaJen Pharma, iTeos Therapeutics, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Cynata Therapeutics, Neoleukin Therapeutics, and Incyte Pharma; and has received research funding from Compass Therapeutics, Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Applied Molecular Transport, Serplus Technology, Heat Biologics, Laevoroc Oncology, iTeos Therapeutics, Genentech, Incyte Pharma, and Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. V.L.P. is the founder of Eniale Immunotherapeutics; reports advisory board participation with Grifols, Ocubio, BRIM, EmmeCell, and Trefoil; consulted for Alumis, BrightStar, Brill Engine, Dompe, Kala, Oculis, Regeneron, Santen, Sylentis, and Thea; and holds equity in Trefoil. R.B.L. is an uncompensated consultant and equity holder in Eniale Immunotherapeutics, Inc; and is a consultant for Kimera Labs, Miramar, FL. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.N.C. is Makana Therapeutics, Miami, FL.

The current affiliation for S.K. is Department of Ophthalmology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan.

The current affiliation for M.R.M.v.d.B. is City of Hope Cancer Center, Los Angeles, CA.

The current affiliation for M.T.A. is F. Widjaja Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Los Angeles, CA.

Correspondence: Robert B. Levy, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Miami School of Medicine, 1600 NW 10th Ave, Miami, FL 33136; email: rlevy@med.miami.edu.

References

Author notes

D.M., S.N.C., B.J.P., and D.W. contributed equally to this study.

All data will be preserved on a secure Box drive maintained by the University of Miami. Large data sets will be shared on public repositories. Biological data will be available in open access publications, and, as permissible, supporting data for figures and tables will be included in a supplemental file. Otherwise, these types of data will be made by the corresponding author, Robert B. Levy (rlevy@med.miami.edu), on request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal