In this issue of Blood, Cottu and colleagues present data from the STOPAGO study demonstrating that nearly half of the patients with chronic ITP who achieved a complete response to thrombopoietin receptor agonists for more than 1 year were able to safely stop therapy and remain stable for up to 4 years.1

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is characterized by a life-threatening drop in platelet count often accompanied by bleeding and bruising. Although first-line corticosteroid therapy is highly effective, many patients will develop either persistent (3- to 12-month duration) or chronic (>12-month duration) ITP, suffering significant side effects from prolonged steroid therapy.2 Subsequent line therapies include splenectomy, rituximab, and thrombopoietin-receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) as steroid-sparing agents, among others. Splenectomy is highly effective but involves undergoing major surgery with a risk for both infection and thrombosis. Although rituximab is favored by many clinicians, only about 20% of patients who receive this therapy will remain in remission at 20 years.3

Since the growth factor thrombopoietin was first purified and cloned in 1994, there has been ongoing interest in stimulating platelet production to maintain a safe platelet count in patients with ITP.4 Early thrombopoietin-directed therapies were limited by complications such as antibody formation and marrow fibrosis. Newer therapies targeting the thrombopoietin receptor have no sequence homology with native thrombopoietin, preventing the formation of antibodies, yet they are highly effective for maintaining a safe platelet count long term with minimal side effects or risks (estimated response rates >80%). Several TPO-RAs are approved for the treatment of chronic ITP, including the injection therapy romiplostim and the oral therapies eltrombopag and avatrombopag. The American Society of Hematology 2019 Guidelines for Immune Thrombocytopenia suggest either splenectomy or a TPO-RA may be considered as second-line therapy in adults with ITP that is refractory to corticosteroids and in those who are corticosteroid-dependent.5 More recently, published data have suggested an immunomodulatory effect of TPO-RA therapy, possibly through increasing regulatory T-cell activity, raising the prospect of discontinuing TPO-RA therapy after sustained therapeutic response.6 Extensive data also suggest long-term TPO-RA therapy is safe.7

The STOPAGO study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03119974) was a prospective, multicenter study across the French ITP reference center network. In that study, all patients had persistent or chronic ITP and had achieved a platelet count >100 × 109/L for at least 2 months on either eltrombopag or romiplostim. After patients were enrolled, TPO-RAs were discontinued according to a standardized tapering schedule.

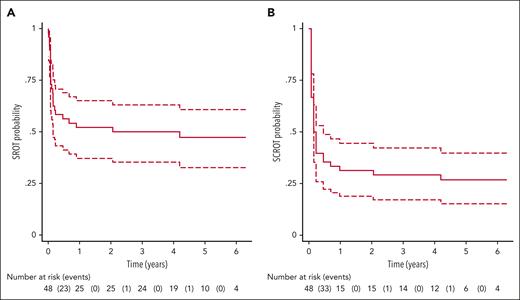

Between September 2017 and February 2020, among 48 patients enrolled in the STOPAGO study, 25 achieved sustained response to therapy at 12 months and were then followed for a minimum of 4 additional years. Most patients (92%) received eltrombopag and had been on this specific TPO-RA for a median of 2.1 years prior to discontinuation. During follow-up, 47.9% of patients maintained a sustained response to therapy (platelet count ≥30 × 109/L and no bleeding without ITP-specific medications) and 39.6% of patients achieved a sustained complete response (platelet count ≥100 × 109/L and no bleeding without ITP-specific medications) at the end of their follow-up (see figure). Among the patients who relapsed, 1 regained a complete response after reinitiation of oral glucocorticoids and eltrombopag therapy. The second patient restarted eltrombopag but required 3 additional lines of therapy, none of which had been effective in returning the patient to a complete response at the time of analysis.

Kaplan-Meier curves of relapse-free probability of SROT (A) and SCROT (B) after thrombopoietin-receptor agonist discontinuation. SCROT, sustained complete response of treatment; SROT, sustained response of treatment. See Figure 1A-B in the article by Cottu et al that begins on page 244.

Kaplan-Meier curves of relapse-free probability of SROT (A) and SCROT (B) after thrombopoietin-receptor agonist discontinuation. SCROT, sustained complete response of treatment; SROT, sustained response of treatment. See Figure 1A-B in the article by Cottu et al that begins on page 244.

In addition to reporting rates of sustained remission, the authors evaluated whether specific risk factors would predict a lack of a sustained response to TPO-RA therapy. Among numerous risk factors evaluated, including age, splenectomy status, and specific TPO-RA therapy used, only chronic ITP as compared with persistent ITP at the time of initiation of TPO-RA therapy was found to be a significant risk factor for nonsustained response.

The major benefit of TPO-RA therapy is avoidance of major surgery and strong immunosuppressive medications, yet the tradeoff is the need to take a daily oral therapy or weekly injection. Nevertheless, the STOPAGO findings question the degree to which lifelong therapy is necessary. If TPO receptor agonists were simply maintaining a safe platelet count through an increase in platelet production, it would be expected that cessation of TPO-RA therapy would lead to a decline in platelet count over time. Given that some patients are able to stop TPO-RA therapy, or even use the treatment as first-line therapy to induce remission, suggests an immunomodulatory effect.

What remains to be seen, however, are clear predictors for those patients in whom TPO-RA therapy may be safely discontinued. The patient population in this study was highly selected for those in whom remission was possible with TPO-RA, so clinicians should be cautious when discontinuing TPO-RA therapy in patients with chronic ITP. Patients with chronic ITP in sustained remission for >12 months on TPO-RA therapy may be able to taper therapy and remain in remission long term, minimizing the need for lifelong therapy.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.T.C. reports serving as a consultant for Takeda; participating on advisory boards for Takeda, Genentech, Sanofi Genzyme, Bayer, and Medzown; and receiving honoraria/travel support from OctaPharma AG and Pfizer.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal