In this issue of Blood, Long et al1 show that the E3 ubiquitin ligase “activating molecule in BECN1-regulated autophagy 1” (AMBRA1) reduces the severity of β-thalassemia by stimulating the autophagy of free α-globin. During red blood cell (RBC) formation, production of the adult hemoglobin tetramer (α2β2) is exquisitely balanced to avoid accumulation of unstable and cytotoxic free α- or β-globin subunits. In β-thalassemia, HBB gene mutations reduce or eliminate β-globin synthesis, leading to a buildup of free α-globin, which forms precipitates that destroy circulating RBCs or their bone marrow precursors.2 Accordingly, genetic variants that reduce free α-globin can lessen or even eliminate the pathophysiology of coinherited β-thalassemia. These modifiers include deletions of 1 or 2 α-globin genes, or numerous variants that enhance the postnatal expression of γ-globin, which pairs with free α-globin to form fetal hemoglobin (α2γ2).2

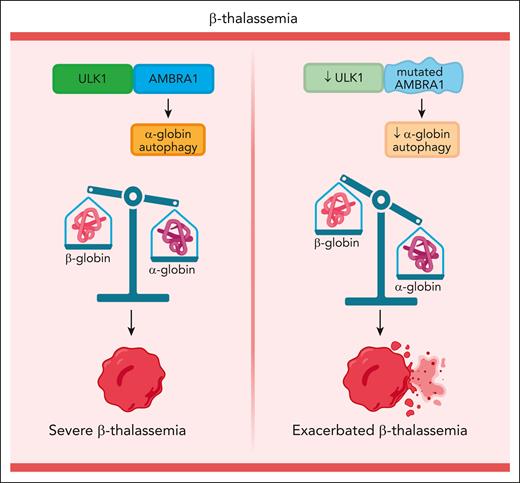

Most cell types contain elaborate mechanisms to eliminate misfolded, unnecessary, or toxic proteins. In β-thalassemic RBC precursors, free α-globin is degraded by autophagy, a process that sequester a cargo into cytosolic vesicles to be delivered to lysosomes.3 In a mouse model for β-thalassemia, disruption of the autophagy-activating Unc-51–like kinase 1 (Ulk1) gene caused accumulation of free α-globin and exacerbated disease pathologies.4 Conversely, enhancement of ULK1-mediated autophagy by treatment with the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 inhibitor rapamycin caused a reduction in free α-globin precipitates and lessening of β-thalassemia phenotypes. Hence, it is possible that autophagy modulates the severity of human β-thalassemia, although this has been difficult to prove. Long et al analyzed whole-genome sequencing data from 1022 patients with β-thalassemia to determine whether naturally occurring genetic variants in 30 autophagy-related (ATG) genes modify disease phenotypes. Remarkably, they identified 4 different AMBRA1 missense mutations that correlated with disease β-thalassemia severity (see figure). Follow-up studies in β-thalassemic mice, a human erythroid cell line, and healthy donor or β-thalassemia patient-derived CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells showed that AMBRA1 reduces β-thalassemia severity by facilitating the autophagic clearance of free α-globin and that some AMBRA1 protein variants identified in β-thalassemic patients are functionally impaired.

The current study is important and interesting for several reasons.1 First, it provides the strongest evidence to date that autophagy of free α-globin reduces the severity of human β-thalassemia. In this manner, β-thalassemia is similar to other “protein aggregation disorders” in which protein quality control mechanisms can protect cells by eliminating disease-specific cytotoxic proteins.3 Second, the findings expand the repertoire of genetic modifiers that influence the severity of β-thalassemia. Third, the work strengthens the hypothesis that pharmacologic enhancement of autophagy could be therapeutic for β-thalassemia. The development of new drugs for β-thalassemia is important because curative treatments, such as allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or autologous genetic therapies, are unlikely to be available for many patients in the immediate future.

Like all successful studies, the current one identifies new avenues for future research. For example, AMBRA1 mutations were detected in patients with β-thalassemia from southern China. Long et al provide a strategy for determining whether variants in AMBRA1 or other ATG genes modify β-thalassemia in distinct populations, including those from Southeast Asia, Mediterranean regions, and India.1 Such studies could identify new proteins and potentially “druggable” molecular pathways that participate in cellular clearance of free α-globin. Additional insights will come from examining how the currently identified AMBRA1 mutations impair autophagy. AMBRA1, ULK1, and Beclin are members of a multiprotein complex that promotes formation of the autophagosome, an early step in autophagy. AMBRA1 stabilizes ULK1 by stimulating its Lys-63 ubiquitination via the E3 ligase TRAF6.5 Consistent with this model, AMBRA1 disruption or Y78C and E595K missense mutations identified in patients with β-thalassemia destabilized ULK1 protein and reduced its steady-state levels. However, AMBRA1 regulates autophagy through interactions with multiple other proteins,6 and further studies are required to better understand how the AMBRA1 mutations detected in β-thalassemia impair free α-globin degradation.

Further investigation into the entire pathway that mediates α-globin autophagy could provide insights beyond β-thalassemia. In erythroid cells, this was shown to be dependent on ULK1 but independent of the canonical autophagy protein ATG5, and therefore most likely mediated through a process termed “noncanonical autophagy” or “Golgi membrane-associated degradation.”4,7,8 Although both canonical autophagy and noncanonical autophagy are stimulated by ULK1, they also use distinct proteins and membrane sorting pathways. Noncanonical autophagy, being ATG5 independent, does not include the formation of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain conjugated to 3-phosphatidylethanolamine (LC3-II) or its recruitment to autophagosomal membranes. Long et al showed that AMBRA1 deficiency reduces the autophagic flux of LC3-II and α-globin, indicating impaired canonical and noncanonical autophagy, respectively. To better understand the clearance of free α-globin in RBC precursors and the associated role of AMBRA1, noncanonical autophagy will require further investigation. As this pathway also facilitates terminal erythroid maturation, at least partly by mediating mitochondrial clearance,9 such studies should illuminate numerous aspects of RBC formation beyond α-globin catabolism. More broadly, investigating AMBRA1- and ULK1-mediated mechanisms of noncanonical autophagy should shed light on the pathophysiology of numerous age-related disorders, including neurodegeneration and cancer.6

In β-thalassemia, during terminal erythroid maturation, β-globin (HBB) gene mutations cause a buildup of free α-globin, which forms toxic intracellular precipitates, causing ineffective erythropoiesis and hemolysis. AMBRA1 missense mutations reduce ULK1-mediated autophagy of free α-globin and exacerbate β-thalassemia. Figure created with BioRender.com.

In β-thalassemia, during terminal erythroid maturation, β-globin (HBB) gene mutations cause a buildup of free α-globin, which forms toxic intracellular precipitates, causing ineffective erythropoiesis and hemolysis. AMBRA1 missense mutations reduce ULK1-mediated autophagy of free α-globin and exacerbate β-thalassemia. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal