In this issue of Blood, Landgren et al1 present the EVIDENCE (Evaluate Minimal Residual Disease as an Intermediate Clinical Endpoint for Multiple Myeloma) meta-analysis of randomized trials in multiple myeloma (MM), demonstrating that treatments with higher rates of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity at 12 months are likely to predict improved clinically meaningful outcomes.

The authors designed the analysis based on US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance to demonstrate that MRD negativity at the prespecified time point of 12 ± 3 months from randomization is reasonably likely to predict long-term progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). The analysis included 8 phase 2 or 3 trials of 4907 patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM). The trial-level associations between MRD negativity and PFS were R2WLSiv 0.67 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43-0.91) and R2copula 0.84 (95% CI, 0.64->0.99). The patient-level association between 12-month MRD negativity and PFS resulted in an odds ratio of 4.02 (95% CI, 2.57-5.46). The correlation between MRD negativity and OS was weaker. An analysis with 4 trials that included 1835 patients with relapsed or refractory MM showed strong patient-level association between MRD and PFS and OS but was not powered for trial-level associations.

On the basis of the results of EVIDENCE and similar analysis produced by the I2TEAMM (International Independent Team for Endpoint Approval of Myeloma Minimal Residual Disease), on April 12, 2024, the Oncology Drugs Advisory Committee unanimously recommended to the FDA the acceptance of MRD as an end point for accelerated approvals in MM.

Understanding the importance of this recommendation requires some insight into the FDA-accelerated approval program.2 The premise of the FDA-accelerated approval program is the need to get new treatments to patients with serious conditions and unmet therapeutic needs before larger randomized trials can be completed to demonstrate the definitive clinical benefit. The program blossomed in oncology, where the “serious” and “unmet need” standards have been met in many diseases, including in MM.

Most of the accelerated approvals have been supported by single-arm trials. However, there have been instances when drugs were approved and remained available for years without a positive confirmatory randomized trial, or simply failed to show clinical benefit in subsequent trials. This resulted in scrutiny of the program and improvements to the accelerated approval mechanism.

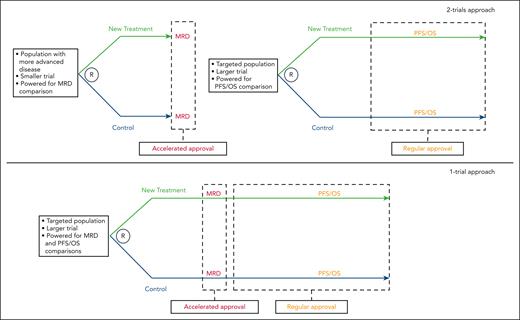

Currently, the FDA favors the design of accelerated approval trials that include a control arm.3 This can be accomplished by a “2-trials” approach. A trial in more advanced disease with a short-term end point allows quick assessment of relative efficacy of a new drug seeking accelerated approval. A subsequent and likely larger trial, in less advanced disease, with traditional clinical benefit end points (PFS or OS) would be performed to support regular approval. The FDA also signaled an interest in an intriguing “1-trial approach” supporting initially accelerated approval based on short-term end point(s), and subsequently regular approval when PFS and OS were available from the same trial (see figure).

The logical question in MM is what short-term efficacy end point is right for the job. Such an end point should be available relatively soon after the start of therapy, be evaluable for all or nearly all patients, and, most importantly, display trial-level association with clinically meaningful end points.3 The work from the EVIDENCE team demonstrates that MRD checks all the boxes and is a great, and likely the only, candidate for the job.

Other short-term efficacy end points in MM, such as overall response and stringent complete response (sCR), feel more natural, are rooted in the myeloma culture, and are arguably simpler and more broadly available. However, they are based in crude reductions of serum and/or urine biomarkers (paraprotein) and bone marrow plasmacytosis, defined arbitrarily and not validated as predictors of long-term clinical benefit in randomized trials.4 Moreover, when reinterpreted in the context of MRD and modern therapy, sCR, once the pinnacle of response, is only a “good thing” because it includes most patients who achieved MRD negativity. Among patients who remain MRD positive, it seems to make little difference if the paraprotein was reduced by 50%, 90%, or 100%.5 Conversely, among patients who become MRD negative, the detection of residual paraprotein may not matter.6 A few decades ago, when therapies were less effective, MRD was not only unavailable, but it was also unnecessary. Current frontline quadruplet regimens followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) result in sCR for near 70% of patients,7-9 making MRD indispensable.

The recently reported GRIFFIN8 and PERSEUS7 studies indicate that ≈85% of patients with NDMM treated with quadruplet induction therapy and ASCT are alive and progression free after 4 years. These 2 trials clearly illustrate the dilemma. As long as we rely exclusively on PFS and OS to adjudicate up-front therapies, we will only take steps on a slow 5- to 10-year cycle. The adoption of MRD as an end point for accelerated drug development will fast-forward this process, potentially adding years of disease control and survival to thousands of patients.

MRD and consequently the EVIDENCE study are not without caveats. There is still heterogeneity in MRD assessment methods, the test requires an uncomfortable bone marrow aspiration, and the association with clinically meaningful end points is not perfect. Work is underway to develop blood-based biomarkers that could mirror or even outperform marrow-based MRD. The universal and uniform adoption of MRD assessment in clinical trials and the use of end points that require sustainability in MRD negativity in the context of modern MM regimens will ensure the next chapters in MRD are written.10

The possibility of accelerated approvals based on an MRD end point generated fears of a never-ending escalation of drugs, cost, and toxicity, in the pursuit of the quick rewards of MRD negativity and regulatory approval. The myeloma community now has a powerful tool that we will be sure to use responsibly, by designing patient-centered and resource-conscious trials that prioritize toxicity, patient preference, and cost without compromising efficacy. MRD will help us do that better. With the same confidence we embrace a new drug for providing higher MRD negativity, we should embrace treatment deescalation if it does not compromise this validated and celebrated efficacy end point.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.J.C. received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Amgen, Genentech, and Caribou; and honoraria from Janssen, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Adaptive Biotechnologies, and Pfizer.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal