Using nanopore sequencing, we showed the feasibility and impact of rapid genomic screening for managing thrombotic microangiopathies in 18 prospective cases, achieving diagnoses in <3 days. We compared the results with standard exome sequencing, cost efficiency, and complement blockade initiation.

TO THE EDITOR:

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) encompasses a variety of clinical conditions characterized by mechanical hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Depending on the underlying cause, various target organs, such as the kidneys, brain, and heart, can be affected.1 In practice, recognizing that TMA involves a multitude of distinct diagnoses with unique treatment approaches, we recently supplemented the diagnostic strategy with rapid (<3 week) genetic analysis.2 Essentially, this strategy involved the following: (1) a thorough search for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and Shiga toxin–mediated hemolytic-uremic syndrome (STEC-HUS); and (2) using whole-exome sequencing (WES) to promptly identify complement-mediated TMA (CM-TMA) pathogenic variants, risk alleles, or cases influenced by cobalamin metabolism abnormalities (pathological variant in metabolism of cobalamin associated C gene [MMACHC]).3 CM-TMAs are largely associated with pathological variants in genes of the alternative complement pathway (CFH, CFI, CD46, C3, and CFB) or hybrid gene formation in the CFHR genes, undetectable using WES.4 Best described as CFHR1/CFH hybrid or fusion genes representing very rare pathological events, they are unlike homozygous CFHR3-CFHR1 deletion, which is well detected by standard WES and is sometimes associated with CFH antibodies in children.5,6 Rapid identification of these genetic anomalies might facilitate or accelerate the use of complement blockage therapy such as eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5, which has drastically changed the prognosis of CM-TMA. Conversely, the detection of nonrelated CM-TMA–associated genetic events could affect patient management, prompting vitamin B12 therapy with biallelic pathological MMACHC, or limit renal biopsy indication.

Our initial strategy relied on sequencing techniques2 such as WES for single nucleotide variants and multiplex ligation–dependent probe amplification for copy number variations,7 leading to turnaround time of 3 to 8 weeks. Given our own clinical needs, we incorporated another sequencing strategy developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies to further reduce turnaround time to just a few days, accelerating treatment and clinical management.8 Beyond shortening the turnaround time, this approach offers several additional benefits associated with long-read compared with short-read sequencing: phasing of alleles, similar detection of single nucleotide variants, CFH/CFHRs hybrid gene detection, and methylation profiling in a single technique. Because of its adaptive sampling method, nanopore sequencing also offers target enrichment, enriching or depleting sequences of interest to ensure adequate coverage of relevant genomic regions at lower consumable and computing cost than whole-genome sequencing.9,10

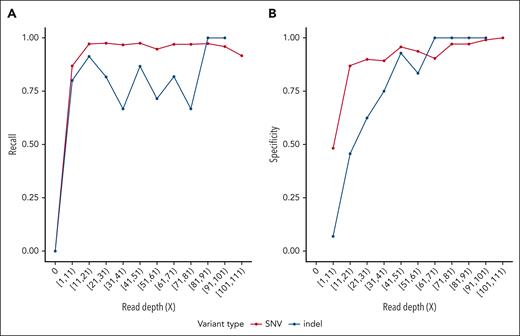

We developed an affordable, multisite, and resource-prospective workflow using nanopore sequencing technology, enabling a turnaround time ranging from 105 hours to 60 hours (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). This protocol allows for faster decision-making regarding patient variant-dependent treatment (mainly complement inhibitors initiation or discontinuation with significant cost reduction) and was applied to 21 patients with TMA, 3 patients retrospectively and 18 patients prospectively. Each patient underwent standard clinically certified WES diagnosis, summarized in supplemental Table 1. The cost of each strategy was calculated for each patient according to the methodology specified (supplemental Table 2), ranging from €1054.25 (PromethION nanopore) to €1195.75 (GridION nanopore) to €2205 (standard WES) depending on the sequencing technology. In Figure 1, we show the sensitivity and recall of variant detection from nanopore sequencing data, using variants identified with WES as ground truth. The mean depth ranges from 18× for samples analyzed on the GridION platform to >50× for samples analyzed on the PromethION sequencer (supplemental Figure 2). The specificity and sensitivity of variant detection on nanopore data is high even at relatively low sequencing depth, demonstrating its reliability as a molecular diagnostic tool in a clinical setting.

Fast-track rapid genomics performance. Analytical performances of SNVs and indel detection in nanopore sequencing data. Recall (fraction of true variant detected by nanopore sequencing) and specificity (fraction of variant detected on nanopore data present in the truth set) are calculated over variants binned by read depth at their respective locus on nanopore data. Variants called on WES data were used as ground truth. (A) (Recall): For SNV detection, recall reached a plateau at a sequencing depth of 20×, indicating optimal recall was achieved at this depth. For indels, recall showed more variability but stabilized at a similar depth. (B) (Specificity): Specificity for SNVs and indels plateaued at ∼40× depth, indicating optimal detection beyond this depth. Variants located in regions susceptible to sequencing artifacts, including ENCODE blacklist regions19 and HLA genes, have been excluded. Five patients presenting an outlier number of discordant variants (fourfold greater than the mean of the cohort) were removed from this analysis. SNV, single nucleotide variant.

Fast-track rapid genomics performance. Analytical performances of SNVs and indel detection in nanopore sequencing data. Recall (fraction of true variant detected by nanopore sequencing) and specificity (fraction of variant detected on nanopore data present in the truth set) are calculated over variants binned by read depth at their respective locus on nanopore data. Variants called on WES data were used as ground truth. (A) (Recall): For SNV detection, recall reached a plateau at a sequencing depth of 20×, indicating optimal recall was achieved at this depth. For indels, recall showed more variability but stabilized at a similar depth. (B) (Specificity): Specificity for SNVs and indels plateaued at ∼40× depth, indicating optimal detection beyond this depth. Variants located in regions susceptible to sequencing artifacts, including ENCODE blacklist regions19 and HLA genes, have been excluded. Five patients presenting an outlier number of discordant variants (fourfold greater than the mean of the cohort) were removed from this analysis. SNV, single nucleotide variant.

From 21 patients, we show 3 paradigmatic cases of TMA that highlight how incorporating fast-track rapid genomic screening in the diagnosis workflow may benefit patient management as a proof of concept.

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients regarding deidentified clinical and personal patient data collection, analysis, and publication. The study was approved by an institutional review board (APHP220461) and the ethic board of Sorbonne Université (CER-2022-009).

Case study 1

A 57-year-old man was admitted to the intensive care unit for syncope and acute respiratory failure (Table 1). Medical history was chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate = 7 mL/min per 1.73 m2) attributed to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis of unknown origin. He presented with a right heart failure attributed to pulmonary hypertension associated with biological TMA, kidney dysfunction (plasma creatinine [PCr] = 686 μmol/L), and hyperhomocysteinemia (340 μmol/L; N < 15). Clinical suspicion pointed to methylmalonic aciduria, but the use of blockade therapy (eculizumab) was also discussed. Standard WES and fast-track rapid genomics were conducted. Both reported a homozygous pathogenic missense variant (class 5 of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics) in MMACHC (NM_015506.3 c.389A>G), associated with cobalamin C disease (as depicted in supplemental Figure 3A). Although the molecular diagnosis was obtained in 5 days with the fast-track rapid genomics analysis, the conventional strategy using WES took 26 days. Unfortunately, the patient died at day 5 after molecular diagnosis despite venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). An even faster molecular diagnosis could have enabled speedier initiation of vitamin B12 treatment, potentially averting the patient's death.2

Diagnostic genetic findings and clinical implications

| Patient . | Gene variation . | Inheritance pattern . | Disease association . | Turnaround time (WES) . | Turnaround time (Fast track) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MMACHC (NM_015506.3 c.389A>G) | Autosomal recessive | Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblC type | 26 d | 5 d |

| 2 | CFH (NM_000186.4 : c.1137G>A, p.W379Ter) | Autosomal dominant | Complement factor H deficiency | 38 d | 3 d |

| 3 | CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene | Autosomal dominant | Complement factor H deficiency | 6 mo | 3 d |

| Patient . | Gene variation . | Inheritance pattern . | Disease association . | Turnaround time (WES) . | Turnaround time (Fast track) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MMACHC (NM_015506.3 c.389A>G) | Autosomal recessive | Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblC type | 26 d | 5 d |

| 2 | CFH (NM_000186.4 : c.1137G>A, p.W379Ter) | Autosomal dominant | Complement factor H deficiency | 38 d | 3 d |

| 3 | CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene | Autosomal dominant | Complement factor H deficiency | 6 mo | 3 d |

cblC, cobalamin C.

Case study 2

A 37-year-old woman (Table 1) with no medical history was admitted for malignant hypertension (186/120 mm Hg) associated with acute kidney injury (PCr = 898 μmol/L) and biological TMA. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and STEC-HUS were ruled out. Hemodialysis was initiated when a uremic syndrome with significant nausea became evident. A fast-track rapid genomics analysis was conducted, yielding results in 3 days. It revealed a likely pathogenic heterozygous variant in CFH (NM_000186.4 :c.1137G>A, p.W379Ter; supplemental Figure 3B), prompting swift eculizumab initiation, and subsequently confirmed by traditional WES protocol. Regrettably, 6 months after the introduction of blockade therapy, the patient still requires hemodialysis.

Case study 3

A 34-year-old patient (Table 1) was admitted for vomiting and diarrhea. He presented with acute kidney injury (PCr = 497 μmol/L) with biological TMA. On kidney biopsy, glomerular TMA associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis lesions was observed. The diagnosis of STEC-HUS was confirmed by the detection of Shiga toxin (stx2b) through polymorphism chain reaction assessment in the stool samples, and the stool culture confirmed the presence of the enterohemorrhagic O128 Escherichia coli clone. Recurrence after initial clinico-biological improvement prompted complement blockade therapy with eculizumab. Genetic analysis by multiplex ligation–dependent probe amplification revealed the presence of a heterozygous CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene 6 months later. DNA was resequenced by nanopore, confirming the CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene identified (CFH1-20::CFHR15-6; supplemental Figure 4). The patient’s parents were sequenced by standard WES and nanopore; no hybrid genes were found (supplemental Figure 5), indicating a de novo CFH/CFHR1 hybrid genes formation. The case illustrates the dynamic nature of this region, subjected to the complex genomic rearrangements that we were subsequently able to detect.11

This study demonstrates the feasibility of integrating a rapid genomic diagnostic strategy within a nephrology intensive care unit for the management of TMA. This approach enables a molecular diagnosis within 3 days, a significant improvement over the 3-week time frame associated with WES. Additionally, using long-read sequencing allows for the identification of genetic abnormalities, including hybrid genes and intronic variants, undetectable in a single assay WES. The prompt diagnosis of CM-TMA is imperative because it supports the evidence-based administration of anti-C5 antibody and elimination of C5 rare variant resistant to C5 blocking. Despite the substantial logistical coordination required, this strategy could potentially decrease both costs and adverse effects linked to unnecessary complement inhibition or procedures. Beyond cost, it may also eliminate the unnecessary invasiveness of a kidney biopsy. However, although rapid genetic testing can confirm a pathological complement variant and responsiveness to C5 blockers or provide an alternative explanation for secondary TMA, a negative result in complement genes still does not exclude immune-mediated CM-TMA or potential response to C5 blockers.12,13 Beyond precluding a lower end-stage kidney survival, the absence of genetic variants in complement genes indicates a low risk of TMA recurrence/relapse in the long run. Nevertheless, more data are needed to ascertain the prognostic value of early genetic information, particularly for C5 blocking response in TMA without rare complement genes variants. Currently, up to 40% of atypical HUS cases in the UK registry treated with C5 blockers do not have complement gene pathological variants or CFH antibodies.14

Given the continuous cost reduction in the expense of genomic analysis,15 the cost-effectiveness of immediate comprehensive genomic analysis is increasingly advantageous. The ability to deliver a genetic diagnosis during the patient’s hospital stay allows for genetic counseling and possible screening for the patient’s family. Additional advantages include the identification of genetic risk factors that may partially elucidate some TMAs (such as the I416L variant of CFI)16,17 and the reclassification of specific phenotypes (retrophenotyping), as noted in previous observations of “nephroangionophthisis.”18

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Felicity Kay for the English editing and Véronique Frémeaux Bacchi for her advice on multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification interpretation.

Part of this work was supported by research funding provided by Alexion Pharmaceuticals (grant 4800065244 to L.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.M., L.M., Y.L., and C.R. were responsible for data curation; and all authors were responsible for manuscript drafting, revision, and critical appraisal.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.R. receives lecture fees from Alexion Pharma France and travel grants. L.M. receives lecture fees from Alexion and Sanofi Pharma and travel grant from Sanofi Pharma France. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Laurent Mesnard, Service de Soins Intensifs Néphrologiques et Rein Aigu, Hôpital Tenon, Département de Néphrologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, 75020 Paris, France; email: laurent.mesnard@aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

N.Y. and C.M. contributed equally to this work.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Laurent Mesnard (laurent.mesnard@aphp.fr).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal