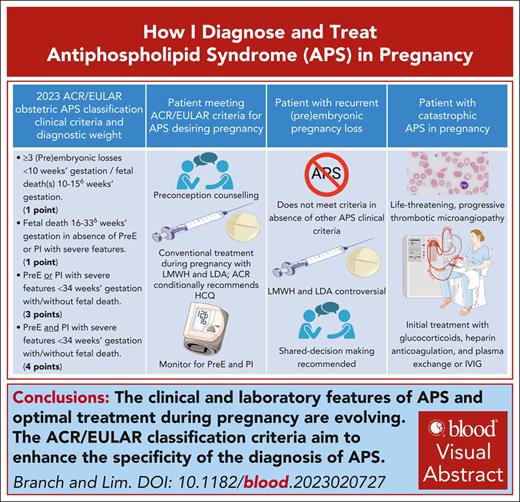

Visual Abstract

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by arterial, venous, or microvascular thrombosis, pregnancy morbidities, or nonthrombotic manifestations in patients with persistently positive antiphospholipid antibodies. These antibodies bind cellular phospholipids and phospholipid–protein complexes resulting in cellular activation and inflammation that lead to the clinical features of APS. Our evolving understanding of APS has resulted in more specific classification criteria. Patients meeting these criteria should be treated during pregnancy according to current guidelines. Yet, despite treatment, those positive for lupus anticoagulant have at least a 30% likelihood of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Patients with recurrent early miscarriage or fetal death in the absence of preeclampsia or placental insufficiency may not meet current classification criteria for APS. Patients with only low titer anticardiolipin or anti–β(2)-glycoprotein I antibodies or immunoglobulin M isotype antibodies will not meet current classification criteria. In such cases, clinicians should implement management plans that balance potential risks and benefits, some of which involve emotional concerns surrounding the patient’s reproductive future. Finally, APS may present in pregnancy or postpartum as a thrombotic microangiopathy, a life-threatening condition that may initially mimic preeclampsia with severe features but requires a very different treatment approach.

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by arterial, venous, or microvascular thrombosis, pregnancy morbidities, or nonthrombotic manifestations in patients with persistently positive antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs).1 APS may occur as a primary condition or as a comorbidity in patients with autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).2,3 aPLs bind cellular phospholipids and phospholipid–protein complexes, resulting in cellular activation and inflammation that ultimately lead to the clinical features of APS, including thrombosis and poor placental vascularization.4 The estimated prevalence and annual incidence of APS is 40 to 50 cases per 100 000 and 1 to 2 cases per 100 000 individuals, respectively.5,6

Previous APS classification criteria7,8 required only a single clinical feature and single laboratory feature. A third revision of the APS classification criteria has recently been published by the American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR; Table 1).1 It was prompted by growing recognition of aPL-associated nonthrombotic clinical manifestations and now clearly evident risk stratification according to clinical risk factors and aPL profile. Experts used rigorous methodology9 to define entry level criteria and additive, weighted clinical and laboratory criteria, in 6 clinical and 2 laboratory domains, respectively. Individual clinical and laboratory features are assigned points, and classification as APS requires a score of ≥3 points from the clinical domain and ≥3 points from the laboratory domain.

ACR/EULAR (2023) APS classification criteria

| Entry criteria . |

|---|

| At least 1 documented clinical criterion,∗ listed hereafter (domains 1-6) |

| plus |

| A positive† aPL test (LA test or moderate-to-high titers of anticardiolipin or anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies [IgG or IgM]) within three years of the clinical criterion |

| ↓ |

| If absent, do not attempt to classify as APS; if present, apply additive criteria |

| ↓ |

| Additive clinical and laboratory criteria |

| Do not count a clinical criterion if there is an equally, or more, likely explanation than APS. |

| Within each domain, only count the highest weighted criterion toward the total score. |

| Entry criteria . |

|---|

| At least 1 documented clinical criterion,∗ listed hereafter (domains 1-6) |

| plus |

| A positive† aPL test (LA test or moderate-to-high titers of anticardiolipin or anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies [IgG or IgM]) within three years of the clinical criterion |

| ↓ |

| If absent, do not attempt to classify as APS; if present, apply additive criteria |

| ↓ |

| Additive clinical and laboratory criteria |

| Do not count a clinical criterion if there is an equally, or more, likely explanation than APS. |

| Within each domain, only count the highest weighted criterion toward the total score. |

| Clinical domains and criteria . | Weight . | Clinical domains and criteria . | Weight . |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Macrovascular (venous thromboembolism [VTE]) | D2. Macrovascular (arterial thrombosis [AT]) | ||

| VTE with high-risk profile | 1 | AT with high-risk CVD profile | 2 |

| VTE without high-risk profile | 3 | AT without high-risk CVD profile | 4 |

| D3. Microvascular | D4. Obstetric | ||

| Suspected, ≥1 of following: | 2 | ≥3 Consecutive (pre)embryonic loss(es) (at <10 w) and/or fetal death(s) (at 10 w, 0 d to 15 w, 6 d) | 1 |

| Livedo racemosa (exam) | |||

| Livedoid vasculopathy lesions (exam) | Fetal death (at 16 w, 0 d to 33 w, 6 d) in the absence of PreE or PI with severe features | 1 | |

| Acute/chronic aPL-nephropathy (exam or laboratory test) | |||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage (symptoms and imaging) | PreE with severe features (at <34 w, 0 d) or PI with severe features (at <34 w, 0 d) with/without fetal death | 3 | |

| Established, ≥1 of the following: | 5 | PreE with severe features (at <34 w, 0 d) and PI with severe features (<34 w, 0 d) with/without fetal death | 4 |

| Livedoid vasculopathy (pathology) | |||

| Acute/chronic aPL nephropathy (pathology) | |||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage (BAL or pathology) | |||

| Myocardial disease (imaging or pathology) | |||

| Adrenal hemorrhage (imaging or pathology) | |||

| D5. Cardiac valve | D6. Hematology | ||

| Thickening | 2 | Thrombocytopenia (lowest, 20-130 × 109/L) | 2 |

| Vegetation | 4 |

| Clinical domains and criteria . | Weight . | Clinical domains and criteria . | Weight . |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Macrovascular (venous thromboembolism [VTE]) | D2. Macrovascular (arterial thrombosis [AT]) | ||

| VTE with high-risk profile | 1 | AT with high-risk CVD profile | 2 |

| VTE without high-risk profile | 3 | AT without high-risk CVD profile | 4 |

| D3. Microvascular | D4. Obstetric | ||

| Suspected, ≥1 of following: | 2 | ≥3 Consecutive (pre)embryonic loss(es) (at <10 w) and/or fetal death(s) (at 10 w, 0 d to 15 w, 6 d) | 1 |

| Livedo racemosa (exam) | |||

| Livedoid vasculopathy lesions (exam) | Fetal death (at 16 w, 0 d to 33 w, 6 d) in the absence of PreE or PI with severe features | 1 | |

| Acute/chronic aPL-nephropathy (exam or laboratory test) | |||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage (symptoms and imaging) | PreE with severe features (at <34 w, 0 d) or PI with severe features (at <34 w, 0 d) with/without fetal death | 3 | |

| Established, ≥1 of the following: | 5 | PreE with severe features (at <34 w, 0 d) and PI with severe features (<34 w, 0 d) with/without fetal death | 4 |

| Livedoid vasculopathy (pathology) | |||

| Acute/chronic aPL nephropathy (pathology) | |||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage (BAL or pathology) | |||

| Myocardial disease (imaging or pathology) | |||

| Adrenal hemorrhage (imaging or pathology) | |||

| D5. Cardiac valve | D6. Hematology | ||

| Thickening | 2 | Thrombocytopenia (lowest, 20-130 × 109/L) | 2 |

| Vegetation | 4 |

| Laboratory domains and criteria . | Weight . | Laboratory domains and criteria . | Weight . |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7. aPL test by coagulation-based functional assay (LA test) | D8. aPL test by solid phase assay (aCL ELISA and/or aβ2GPI ELISA [persistent]) | ||

| Positive LA (single, 1 time) | 1 | Moderate-to-high-positive (IgM) (aCL and/or aβ2GPI) | 1 |

| Positive LA (persistent) | 5 | Moderate-to-high-positive (IgG) (aCL and/or aβ2GPI) | 4 |

| High-positive (IgG) (aCL or aβ2GPI) | 5 | ||

| High-positive (IgG) (aCL and aβ2GPI) | 7 | ||

| Total score | |||

| Classify as APS for research purposes if there are at least 3 points from clinical domains AND at least 3 points from laboratory domains | |||

| Laboratory domains and criteria . | Weight . | Laboratory domains and criteria . | Weight . |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7. aPL test by coagulation-based functional assay (LA test) | D8. aPL test by solid phase assay (aCL ELISA and/or aβ2GPI ELISA [persistent]) | ||

| Positive LA (single, 1 time) | 1 | Moderate-to-high-positive (IgM) (aCL and/or aβ2GPI) | 1 |

| Positive LA (persistent) | 5 | Moderate-to-high-positive (IgG) (aCL and/or aβ2GPI) | 4 |

| High-positive (IgG) (aCL or aβ2GPI) | 5 | ||

| High-positive (IgG) (aCL and aβ2GPI) | 7 | ||

| Total score | |||

| Classify as APS for research purposes if there are at least 3 points from clinical domains AND at least 3 points from laboratory domains | |||

ACR/EULAR (2023) APS classification criteria modified from Barbhaiya et al.1

aCL and aβ2GPI moderate (40-79 U) and high (≥80 U) thresholds should be determined based on standardized ELISA results, not based on other testing modalities such as new automated platforms with variations of the solid phase (eg, magnetic microparticles and microspheres) and various detection systems (eg, chemiluminescent immunoassay, multiplex flow immunoassay, or flow cytometry).

AT, arterial thrombosis; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; D, domain; d, day; VTE, venous thrombosis or embolism; w, week(s).

For detailed definitions of the clinical criteria and documentation, readers are referred to the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria document.1

LA assay performed and interpreted based on the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis guidelines.46

This review focuses on obstetric and laboratory features of APS based on ACR/EULAR classification criteria and the management of APS in pregnancy. Regarding laboratory criteria, we use the term "low-positive" to indicate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results above the upper end of the reference range but below the threshold for moderate-to-high positive, as described in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria. Using 4 real-world cases, we provide readers with a sense of diagnostic certainties and uncertainties, and management strategies and their shortcomings in the context of the ACR/EULAR classification criteria.

Case 1

A 31-year-old patient with APS is now considering a second pregnancy. She had a deep vein thrombosis at age 24 years, at which time a diagnosis of APS was confirmed by a repeatedly positive lupus anticoagulant (LA) and high-positive immunoglobulin G (IgG) anticardiolipin antibody (aCL) of 94 units and IgG anti–β(2)-glycoprotein I antibody (aβ2GPI) of 83 units. She is maintained on long-term warfarin anticoagulation.

In her first pregnancy, the patient was switched from warfarin to therapeutic-dose low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and low-dose aspirin (LDA) at 5 weeks of gestation. At 28 weeks, 3 days (283 weeks) of gestation, she presented with right upper quadrant pain and a blood pressure of 165/100 mm Hg. A diagnosis of preeclampsia (PreE) with severe features, including the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome), was made (Table 2).

Laboratory data for case 1 and case 3

| Data for case 1 on admission and through hospital day 3 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory testing . | On admission . | At 12 hours . | On day 3 . |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.3 | 11.2 | 10 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 33.5 | 32.8 | 30.1 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 90 | 103 | 73 |

| Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 133 | 125 | 266 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 100 | 108 | 175 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (mg/dL) | 400 | 378 | 450 |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dL) | Undetectable | Undetectable | Undetectable |

| Spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio | 0.9 | Not performed | Not performed |

| Data for case 1 on admission and through hospital day 3 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory testing . | On admission . | At 12 hours . | On day 3 . |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.3 | 11.2 | 10 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 33.5 | 32.8 | 30.1 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 90 | 103 | 73 |

| Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 133 | 125 | 266 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 100 | 108 | 175 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (mg/dL) | 400 | 378 | 450 |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dL) | Undetectable | Undetectable | Undetectable |

| Spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio | 0.9 | Not performed | Not performed |

| Data for case 3 on postpartum days 4 and 5 . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory testing . | On presentation to emergency department (postpartum day 4) . | Postpartum day 5 . |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.3 | 6.5 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 22.4 | 20.5 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 75 | 60 |

| Creatinine | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 458 | 501 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 623 | 657 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (mg/dL) | 675 | 720 |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dL) | Undetectable | Undetectable |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 12 | |

| Partial thromboplastin time (s) | 68 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 323 | |

| Ammonia level (μmol/L) | 42 | |

| Peripheral smear | ≥3 schistocytes per high power field (Figure 2) | |

| Data for case 3 on postpartum days 4 and 5 . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory testing . | On presentation to emergency department (postpartum day 4) . | Postpartum day 5 . |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.3 | 6.5 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 22.4 | 20.5 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 75 | 60 |

| Creatinine | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 458 | 501 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 623 | 657 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (mg/dL) | 675 | 720 |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dL) | Undetectable | Undetectable |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 12 | |

| Partial thromboplastin time (s) | 68 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 323 | |

| Ammonia level (μmol/L) | 42 | |

| Peripheral smear | ≥3 schistocytes per high power field (Figure 2) | |

Obstetric ultrasound evaluations found a growth-restricted singleton fetus (estimated fetal weight of less that the fifth percentile for gestational age) and oligohydramnios. Fetal umbilical artery Doppler interrogation revealed elevated blood flow resistance indices and absent forward flow in diastole, features indicative of placental insufficiency (PI).1

The patient was admitted for management of PreE, including close fetal and maternal surveillance. LMWH was held in lieu of the possible need for delivery. Antenatal steroids were administered to enhance fetal lung maturation. Repeat laboratory studies 12 hours after admission are shown in Table 2.

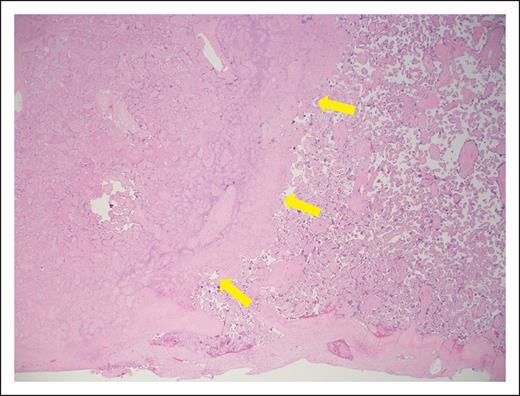

On hospital day 3, worsening features of HELLP syndrome (Table 2) and worsening fetal umbilical artery Doppler assessments required delivery. Following delivery, maternal blood pressure was adequately controlled with oral labetalol, and therapeutic LMWH was restarted 24 hours after cesarean delivery. Maternal laboratory parameters returned to normal by postoperative day 4. Placental histopathologic examination found widespread villous infarction indicative of maternal malperfusion10 (Figure 1). The small-for-gestational age neonate had a hospital course complicated by multiple medical comorbidities, requiring a hospital stay of 62 days.

Photomicrograph of placental section (hematoxylin and eosin, low power). The maternal surface is at the bottom. There is villous infarction on the left (yellow arrows), and accelerated villous maturation seen on the right. These findings are indicative of vascular malperfusion, as described in APS pregnancy.10

Photomicrograph of placental section (hematoxylin and eosin, low power). The maternal surface is at the bottom. There is villous infarction on the left (yellow arrows), and accelerated villous maturation seen on the right. These findings are indicative of vascular malperfusion, as described in APS pregnancy.10

The patient is seeking your consultation regarding the risks of undertaking another pregnancy and how it might best be managed.

Case 2A

An otherwise healthy 39-year-old G4P0030 patient has had 3 prior miscarriages within the past 2 years, all at <10 weeks of gestation. Evaluations for recurrent (pre)embryonic pregnancy loss (RPL)11,12 were negative, although IgG aCL and IgG aβ2GPI results were low-positive at 32 units and 27 units, respectively. Other aPL results were negative. Repeat aPL testing was not performed. She is now pregnant at 84 weeks of gestation via in vitro fertilization. Her infertility provider had made a diagnosis of APS and prescribed enoxaparin 40 mg once daily and LDA daily. Her obstetrician-gynecologist seeks your advice regarding the diagnosis and appropriate management.

Case 2B

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G3P0030 patient is referred because an evaluation for RPL found moderate-positive IgM aβ2GPI levels (44 units, with repeat result of 53 units 12 weeks later.) Tests for LA, IgG and IgM aCL, and IgG aβ2GPI are negative, as are other recommended evaluations for RPL.11,12 Her 3 pregnancy losses occurred at <10 weeks of gestation. Her obstetrician-gynecologist would like your advice regarding a possible diagnosis of APS and appropriate management in pregnancy.

Case 3

A 27-year-old G3P1203 patient is now 5 days after vaginal delivery after induction of labor at 355 weeks of gestation for PreE with severe features. Her vaginal delivery was uncomplicated. Her healthy newborn was of normal weight. Her postpartum hospital course was normal except for mildly elevated blood pressures for which she was treated with extended-release nifedipine 30 mg once daily.

The patient presented to the emergency department on postpartum day 4 with severe right upper quadrant pain and a blood pressure of 145/93 mm Hg with normal pulse rate and oxygen saturation. Initial laboratory results are shown in Table 2. A working diagnosis of HELLP syndrome was made.

On the day of consultation (postpartum day 5), the laboratory parameters had worsened (Table 2) and imaging of the abdomen was concerning for renal, hepatic, and splenic infarcts. Testing for LA is positive; IgG and IgM aCL are 76 units and 98 units, respectively; and IgG and IgM aβ2GPI are 112 units and 85 units, respectively.

How I diagnose obstetric APS

Obstetric clinical features of APS

The obstetric clinical features of APS (Table 1) are each somewhat common in the general population, and none are highly specific to APS. The ACR/EULAR classification criteria recognize 3 obstetric clinical features: RPL, fetal death, and PreE and/or PI diagnosed at <34 weeks of gestation. The greatest diagnostic weight is placed on PreE and/or PI with severe features at <34 weeks of gestation, with or without fetal death. Compared with previous criteria,7,8 far less diagnostic weight is placed on early pregnancy loss and fetal death in the absence of PreE or PI with severe features.

RPL and fetal death

The terminology of pregnancy loss lacks consensus13 and may seem confusing to the nonobstetrician. The ACR/EULAR classification criteria distinguish RPL at <10 weeks of gestation from fetal death at ≥10 weeks of gestation and further categorize fetal death into those occurring at 100 to 156 weeks and at ≥16 weeks of gestation. This categorization represents an effort to recognize different embryo-fetal developmental periods in which the causes of pregnancy loss may vary14 and is intended to encourage investigation of the subsets of pregnancy loss with regard to aPLs.

American and European reproductive health guidelines regarding the evaluation of patients with a chief complaint of RPL recommend aPL testing in patients with ≥2 losses.11,12 RPL is a common reproductive complication, occurring in 1% to 2% of couples.12 A majority of cases are not apparently due to a single, treatable etiology.15,16 In contrast to reproductive health guidelines,11,12 the ACR/EULAR classification criteria for APS define RPL at <10 weeks gestation as ≥3 losses, with the goal of enhancing the specificity of the diagnosis of APS for research.

With regard to APS as a possible cause of RPL, limitations of the literature include lack of discrimination between losses before and after 10 weeks of gestation, incomplete evaluation for other causes of miscarriage, inclusion of low-positive aPLs, and absence of confirmatory aPL testing.4,17 One review of studies through 2011 concluded that the median frequencies of LA, aCL, and aβ2GPI in patients with RPL were low (0%, 2%, and 4%, respectively),18 and a more recent meta-analysis found incredulous, wide-ranging frequencies of LA and aCL in patients with RPL (1.8%-36.5% and 2%-88.1%, respectively).19 Retrospective analyses of single-center data20,21 found the rate of aPLs in patients with RPL to be similar to that of the general population. A secondary analysis of a prospective trial of LDA for prevention of miscarriage in patients with ≤2 prior miscarriages found only 1% of >1000 women had moderate-to-high titer aCL or aβ2GPI,22 and the rate of miscarriage in the study pregnancy was similar in women with or without aPLs. Given current uncertainties about the relationships between aPLs and RPL, this clinical feature carries a low weight in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria. Experts have called for well-designed studies regarding aPLs and miscarriage.12,17,23

Intrauterine demise of the fetus at ≥10 weeks and <20 weeks of gestation is estimated to occur in up to 1% of pregnancies,16 with the majority occurring at <16 weeks.24 Etiologies are numerous and include structural, genetic, and infectious causes. Systematic reviews have concluded that LA and aCL25 but not aβ2GPI25-27 were significantly associated with fetal death at ≥10 weeks of gestation. However, existing studies are flawed by incomplete evaluation for other causes of fetal death, inclusion of low-positive aPLs, absence of confirmatory aPL testing, and uncertainties about the gestational age of fetal death. Because of uncertainties regarding the relationship between aPLs and fetal death at 100 to 156 weeks of gestation, this clinical feature carries a low weight in the classification criteria.

Fetal death after 160 weeks of gestation occurs in ∼1% to 2% of pregnancies.28-30 Fetal death at ≥20 weeks of gestation is commonly referred to as stillbirth and is the best studied with regard to aPLs. A multicenter, population-based, case-control study of >550 stillbirths and >1500 live births found positive tests for aPLs (aCL or aβ2GPI) in 56 of 582 (9.6%) of stillbirths, a threefold to fivefold increased odds compared with live births.31 Fetal death occurred in 10% to 12% of treated APS pregnancies in 2 prospective, observational studies.32,33 Experience holds that APS-related fetal death at or beyond 16 weeks of gestation is typically accompanied by evidence of PI, characterized by such features as fetal growth restriction (FGR), and is often accompanied by PreE with severe features. Given that there are numerous other causes of fetal death, including hematologic, structural, genetic, and infectious causes, the ACR/EULAR classification criteria assign a low weight to fetal death at ≥160 weeks of gestation in the absence PreE and/or PI with severe features.

PreE and/or PI with severe features

PreE with severe features at <34 weeks of gestation, with or without evidence of PI, carries the highest weight in the obstetric domain of the ACR/EULAR classification criteria.1 PreE with severe features is defined according to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines34,35 and PI with severe features is described in Table 3. PreE with severe features complicates 2% to 2.5% of pregnancies,36,37 and PreE with severe features at <34 weeks of gestation occurs in ∼1 in 200 (0.5%) pregnancies.38,39 PreE is well known to be associated with PI,38 and both are associated with an increased risk of fetal death, particularly in the absence of appropriate fetal monitoring and timely delivery. A 2011 meta-analysis of case-control studies found that LA and aCL were significantly associated with PreE,25 and LA also was associated with FGR, a feature of PI. A 2022 meta-analysis found an association between FGR and aCL.40 The only prospective study of aPLs in women presenting with PreE or PI with severe features found that 11.5% of cases were LA and/or moderate-to-high aCL or aβ2GPI positive, compared with 1.4% of matched controls.41

ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria definitions of PreE with severe features and PI with severe features

| PreE with severe features34,35 |

| PreE with severe features is diagnosed when a patient with PreE (gestational hypertension with proteinuria) or gestational hypertension alone has ≥1 of the following: |

| Severe blood pressure elevation: systolic blood pressure of ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of ≥110 mm Hg on 2 occasions, at least 4 hours apart while the patient is on bedrest (antihypertensive therapy may be initiated upon confirmation of severe hypertension, in which case severe blood pressure elevation criteria can be satisfied without waiting until 4 hours have elapsed) |

| Central nervous system dysfunction: new-onset cerebral or visual disturbance including photopsia, scotomata, cortical blindness, retinal vasospasm, severe headache, or headache that persists and progresses despite analgesic therapy, and altered mental status |

| Abdominal pain, hepatic abnormality: severe persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain unresponsive to medication and/or serum transaminase of ≥2-times upper-limit-of-normal range |

| Thrombocytopenia: <100 × 109/L |

| Renal dysfunction: progressive renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.1 mg/dL] or a doubling of the serum creatinine level in the absence of other causes of renal impairment) |

| Pulmonary edema |

| Placental insufficiency with severe features |

| Intrauterine fetal growth restriction defined as ultrasound fetal biometry–estimated fetal weight of <10th percentile for gestational age OR small-for-gestational-age postnatal birth weight defined as <10th percentile for gestational age in the absence of fetal-neonatal syndromes or genetic conditions associated with growth restriction AND ≥1 of the following: |

| Abnormal or nonreassuring fetal surveillance test(s) suggestive of fetal hypoxemia, for example, a nonreactive nonstress test |

| Abnormal doppler flow velocimetry waveform analysis suggestive of fetal hypoxemia, for example, absent end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery |

| Severe intrauterine fetal growth restriction suggested by fetal biometry indicating an estimated fetal or postnatal birth weight of <3rd percentile for gestational age |

| Oligohydramnios, for example, an amniotic fluid index of ≤5 cm, or deepest vertical pocket of <2 cm |

| Maternal vascular malperfusion on placental histology, suggested by placental infarction, decidual vasculopathy, and/or thrombosis |

| PreE with severe features34,35 |

| PreE with severe features is diagnosed when a patient with PreE (gestational hypertension with proteinuria) or gestational hypertension alone has ≥1 of the following: |

| Severe blood pressure elevation: systolic blood pressure of ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of ≥110 mm Hg on 2 occasions, at least 4 hours apart while the patient is on bedrest (antihypertensive therapy may be initiated upon confirmation of severe hypertension, in which case severe blood pressure elevation criteria can be satisfied without waiting until 4 hours have elapsed) |

| Central nervous system dysfunction: new-onset cerebral or visual disturbance including photopsia, scotomata, cortical blindness, retinal vasospasm, severe headache, or headache that persists and progresses despite analgesic therapy, and altered mental status |

| Abdominal pain, hepatic abnormality: severe persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain unresponsive to medication and/or serum transaminase of ≥2-times upper-limit-of-normal range |

| Thrombocytopenia: <100 × 109/L |

| Renal dysfunction: progressive renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.1 mg/dL] or a doubling of the serum creatinine level in the absence of other causes of renal impairment) |

| Pulmonary edema |

| Placental insufficiency with severe features |

| Intrauterine fetal growth restriction defined as ultrasound fetal biometry–estimated fetal weight of <10th percentile for gestational age OR small-for-gestational-age postnatal birth weight defined as <10th percentile for gestational age in the absence of fetal-neonatal syndromes or genetic conditions associated with growth restriction AND ≥1 of the following: |

| Abnormal or nonreassuring fetal surveillance test(s) suggestive of fetal hypoxemia, for example, a nonreactive nonstress test |

| Abnormal doppler flow velocimetry waveform analysis suggestive of fetal hypoxemia, for example, absent end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery |

| Severe intrauterine fetal growth restriction suggested by fetal biometry indicating an estimated fetal or postnatal birth weight of <3rd percentile for gestational age |

| Oligohydramnios, for example, an amniotic fluid index of ≤5 cm, or deepest vertical pocket of <2 cm |

| Maternal vascular malperfusion on placental histology, suggested by placental infarction, decidual vasculopathy, and/or thrombosis |

ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria definitions of PreE with severe features and PI with severe features as modified from Barbhaiya et al.1

Catastrophic APS

Catastrophic APS (CAPS)42 is a severe complication of APS that can occur during pregnancy or the postpartum period.43,44 Fortunately, CAPS only develops in a small subgroup of patients diagnosed with APS but may be the initial presentation of APS. It is characterized by a life-threatening, systemic thromboinflammatory state resulting in the rapid development of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and multiorgan damage due to ischemia. During pregnancy, the initial presentation of CAPS is most likely to be confused with HELLP syndrome.44,45 Unlike HELLP syndrome, CAPS typically follows a course of progressive deterioration despite delivery and the usual supportive measures used in PreE. In CAPS, the central nervous system, skin, and kidneys are commonly affected; and the heart, lungs, liver, and gastrointestinal tract may also be affected. Early recognition of CAPS is essential because mortality is nearly 40%.43 Criteria for definite and probable CAPS are shown in Table 4.42

Classification criteria for CAPS

| Criteria |

| 1. Evidence of involvement of ≥3 organs, systems, tissues, or a combination |

| 2. Development of manifestations simultaneously or in <1 week |

| 3. Confirmation by histopathology of small-vessel occlusion in at least 1 organ or tissue∗ |

| 4. Laboratory confirmation of the presence of aPL antibodies according to international criteria1 |

| Definite CAPS |

| All 4 aforementioned criteria |

| Probable CAPS |

| All 4 aforementioned criteria, except only 2 organs, systems, tissues, or a combination involved; or |

| All 4 aforementioned criteria, except for the absence of laboratory confirmation of antiphospholipid antibodies by repeat testing; or |

| Criteria 1, 2, and 4; or |

| Criteria 1, 3, and 4, with the development of a third event >1 week but within 1 month of presentation, despite anticoagulation |

| Criteria |

| 1. Evidence of involvement of ≥3 organs, systems, tissues, or a combination |

| 2. Development of manifestations simultaneously or in <1 week |

| 3. Confirmation by histopathology of small-vessel occlusion in at least 1 organ or tissue∗ |

| 4. Laboratory confirmation of the presence of aPL antibodies according to international criteria1 |

| Definite CAPS |

| All 4 aforementioned criteria |

| Probable CAPS |

| All 4 aforementioned criteria, except only 2 organs, systems, tissues, or a combination involved; or |

| All 4 aforementioned criteria, except for the absence of laboratory confirmation of antiphospholipid antibodies by repeat testing; or |

| Criteria 1, 2, and 4; or |

| Criteria 1, 3, and 4, with the development of a third event >1 week but within 1 month of presentation, despite anticoagulation |

Classification criteria for CAPS as modified from Asheron et al.42

For histopathologic confirmation, significant evidence of thrombosis must be present, although vasculitis may coexist occasionally.

Laboratory features of APS

The ACR/EULAR classification criteria require the persistent presence of ≥1 of 3 aPLs: LA, aCL, or aβ2GPI. To be considered positive, test results must meet specific criteria and the test must be performed within 3 years of the clinical event for which the diagnosis is being considered.1 The three tests should be performed concurrently, and if positive, confirmatory testing for persistence should be done no sooner than 12 weeks later.

LA

LA is identified in patient plasma when a sequence of clotting tests demonstrates: (1) prolongation of a phospholipid-dependent clotting test; (2) evidence for an inhibitory effect in patient plasma; and (3) evidence that the inhibitory effect can be quenched by excess phospholipids.46 Testing should be done on samples collected when the patient is not receiving anticoagulant therapy46 because anticoagulants may cause false positive results. Results should be interpreted with caution in the acute clinical setting because elevated levels of acute phase reactants can interfere with test results.46

aCL and aβ2GPI antibodies

Current classification criteria include IgG and IgM aCL and aβ2GPI at moderate-to-high titer, as detected in standardized ELISA (Table 1). Moderate-to-high titer aCL and aβ2GPI results are typically defined as ≥40 units, results that are ≥99th percentile in healthy controls.47 Laboratories often report ELISA results below these thresholds as indeterminate, weakly positive, or low-positive.

Interpretation of aPL results: antiphospholipid profiles and diagnostic weights

A persistently positive LA is the aPL most predictive of adverse obstetric (and thrombotic) outcomes32,48,49 and, hence, carries a weight of 5 points in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria. Low-positive aCL and aβ2GPI results are of uncertain significance and are not part of the ACR/EULAR classification criteria; they should be interpreted with caution. Also, IgG aCL and aβ2GPI are of more clinical importance than IgM.50,51 Hence, the ACR/EULAR classification criteria place less diagnostic weight on isolated moderate-high positive IgM isotype aCL or aβ2GPI. Patients who are “triple-positive” for all aPLs are at highest risk of development of thrombotic and obstetric complications.52-54

Clinical reality and practice

The ACR/EULAR classification criteria are aimed at enhancing the specificity of APS diagnosis to improve the quality of APS research rather than to dogmatically guide clinical practice. Management of people who do not meet strict classification criteria frequently requires thoughtful clinical judgement to balance medical risks and potential benefits. Additionally, most patients with pregnancy loss or early delivery for PreE and/or PI feel that one of the most important aspects of their life, that of having healthy children, is under siege.55 In this setting, decisions about the use of LMWH is often a patient-led response to their fear of not being able to bear children, and the physician’s decision-making role becomes one of permission and support55 while recognizing the evidence, or lack thereof, and risks.

How I manage APS in pregnancy

Risk assessment before conception

Among individuals with APS meeting ACR/EULAR international criteria, the likelihood of obstetric morbidity in pregnancy varies depending upon clinical history and laboratory features. Patients with a past history of thrombosis, SLE, otherwise unexplained fetal death, or early delivery for PreE with severe features are at increased risk of recurrence of these adverse outcomes, even with standard treatment with a heparin agent plus LDA.32,33,53 The prospective, observational PROMISSE study32 found that prior thrombosis or SLE were associated with approximately twofold increased relative risks for adverse pregnancy outcomes. In the retrospective PREGNANTS study,53 the live birth rate was significantly lower in patients with APS with a history of thrombosis for every aPL combination. In contrast, second- or third-trimester adverse obstetric outcomes are infrequent in patients whose only APS-related feature was RPL.23,33

Regarding laboratory features, the majority of studies but not all56 find that the presence of LA, and particularly triple aPL positivity, predicts higher rates of adverse obstetric outcomes, despite standard treatment.32,54,57 The prospective, observational PROMISSE study, which confirmed aPL results in all patients in a central laboratory, found that patients who were LA positive experienced a 39% rate of a composite outcome that included fetal death, preterm delivery because of PreE or PI, small-for-gestational-age infant, or neonatal death due to complications of prematurity.32 The PREGNANTS study found that patients who were triple-positive had only a 30% rate of successful pregnancy despite treatment.53 A recent retrospective study of 55 pregnant patients with persistently positive aPLs also found that LA was the strongest predictor of adverse pregnancy outcomes, followed by aβ2GPI IgG.48 Patients with both LA and aβ2GPI IgG had a 52% rate of adverse outcomes despite treatment. The authors of this study accounted for potential confounders such as maternal age, obesity, hypertension, and obstetric history, as well as immunoassay titers and isotypes.

In the absence of LA positivity, evidence suggests that aCL or aβ2GPI also are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Retrospective studies58-61 found that low-positive aCL and/or aβ2GPI, mostly defined as those between the 95th and 99th percentile, may be of clinical significance. One group found that persistent low-positive aCL (<99th percentile) in untreated pregnancies of patients with RPL was associated with a higher subsequent pregnancy loss rate,62 and a 2006 meta-analysis found that IgG aCL at both low-positive and moderate-to-high-positive levels were associated with pregnancy loss.63 Two retrospective studies48,53 found that low-positive aCL or aβ2GPI were associated with pregnancy morbidity and that treatment appeared to improve outcomes. Finally, the prospective PROMISSE study found that patients who had received treatment and who were LA negative with IgG aCL or aβ2GPI of any titer had rates of adverse outcome of <15%.32 Because none of the quoted studies were prospective trials, experts have called for properly designed trials, particularly among patients who are LA negative with low-positive aCL or aβ2GPI.23

The significance of aPL IgM isotype, particularly isolated IgM results, with regard to risk, is a subject of debate. A prospective study of low-risk nulliparas64 found the relative risk of an adverse pregnancy outcome was not increased for IgM aCL, and the retrospective analysis by Pregnolato et al48 found that IgM isotype aCL or aβ2GPI alone or combined did not affect risk. One single-center, retrospective study found that IgM aCL was associated with a lower risk of PreE.56

Management and treatment

Case 1

Optimal care would provide the patient who has established APS meeting ACR/EULAR criteria with expert information regarding maternal and fetal risks so that they can decide whether undertaking pregnancy meets her reproductive goals. Patients for whom pregnancy-associated risks are unacceptable should be provided with comprehensive counseling about contraceptive options.65 Among patients opting to undertake pregnancy, those with underlying rheumatic disease should be advised to enter pregnancy with quiescent/low disease activity. Assessments before conception should include aPL confirmation, evaluation of renal status and blood pressure, and complete blood count.

Well-designed trials to determine the efficacy and safety of treatments to improve obstetric outcomes in patients meeting classification criteria for APS are lacking. Pregnancies treated with heparin plus LDA appear to be at low risk for maternal thrombotic events. In the PROMISSE study of well-characterized APS patients, 3 of 178 (1.7%) patients who received treatment had a thrombotic event (J. E. Salmon, written communication, 22 January 2024). In the ongoing IMPACT trial (NCT03152058) of patients with LA-positive APS, 1 of 43 completed pregnancies (2.3%) was complicated by an arterial thrombotic event (stroke) (D. W. Branch and J. E. Salmon, written communication, 22 January 2024). Among treated APS pregnancies, the rate of major hemorrhage is 3%, with emergency cesarean delivery being a significant risk.66 Treatment does not eliminate the risk of PreE and/or PI, although it varies with aPL profile. The overall rate of PreE and/or PI in treated pregnancies is 9% to 10%, and is twofold to fourfold higher in patients with LA.32,49 Fetal death occurs in 10% to 12% of treated APS pregnancies,32,33,49 and the relative risk is twofold to threefold higher in patients with LA.32

A summary of current treatment guidelines65,67 for APS in pregnancy are shown in Table 5. Given the risks of PreE and/or PI in these patients, experts recommend careful antepartum monitoring of fetus and mother.68

| APS history . | European League Against Rheumatism . | American College of Rheumatology . |

|---|---|---|

| Obstetric APS without a history of thrombosis | Heparin or LMWH, thromboprophylactic dose,∗ initiated with demonstration of intrauterine viability and continued for 6 weeks postpartum LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE | LMWH, thromboprophylaxis dose,∗ initiated with demonstration of intrauterine viability and continued for 6-12 weeks postpartum LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE and conditionally‡ recommended for patients with APS |

| Thrombotic APS with or without a history of obstetric APS§ | Heparin or LMWH, therapeutic dose, typically started before conception or by 6 weeks of gestation LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum | LMWH, therapeutic dose, typically started before conception or by 6 weeks of gestation LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE and conditionally‡ recommended for patients with APS For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum |

| APS with history of adverse pregnancy outcome despite standard treatment | Heparin or LMWH, typically started before conception or by 6 weeks of gestation. Consider increasing dose to therapeutic if prior adverse outcome occurred on thromboprophylactic dose LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE; consider addition of HCQ in patients without SLE Consider prednisolone, 10 mg daily in first trimester Use of IVIG in highly selected patients For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum | LMWH at dose appropriate for thrombosis history‖ LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE and conditionally‡ recommended for patients with APS IVIG, low-dose prednisone, increased dose of heparin/LMWH, and HCQ have all been suggested as additional or alternative treatments Strong recommendation against adding prednisone For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum |

| APS history . | European League Against Rheumatism . | American College of Rheumatology . |

|---|---|---|

| Obstetric APS without a history of thrombosis | Heparin or LMWH, thromboprophylactic dose,∗ initiated with demonstration of intrauterine viability and continued for 6 weeks postpartum LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE | LMWH, thromboprophylaxis dose,∗ initiated with demonstration of intrauterine viability and continued for 6-12 weeks postpartum LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE and conditionally‡ recommended for patients with APS |

| Thrombotic APS with or without a history of obstetric APS§ | Heparin or LMWH, therapeutic dose, typically started before conception or by 6 weeks of gestation LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum | LMWH, therapeutic dose, typically started before conception or by 6 weeks of gestation LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE and conditionally‡ recommended for patients with APS For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum |

| APS with history of adverse pregnancy outcome despite standard treatment | Heparin or LMWH, typically started before conception or by 6 weeks of gestation. Consider increasing dose to therapeutic if prior adverse outcome occurred on thromboprophylactic dose LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE; consider addition of HCQ in patients without SLE Consider prednisolone, 10 mg daily in first trimester Use of IVIG in highly selected patients For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum | LMWH at dose appropriate for thrombosis history‖ LDA beginning before conception or with documentation of pregnancy HCQ† recommended for patients with SLE and conditionally‡ recommended for patients with APS IVIG, low-dose prednisone, increased dose of heparin/LMWH, and HCQ have all been suggested as additional or alternative treatments Strong recommendation against adding prednisone For patients on long-term anticoagulation postpartum, bridge to warfarin postpartum |

HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IVIG, intravenous immune globulin.

There is no consensus regarding the optimal thromboprophylactic dose of LMWH in APS. For enoxaparin, 0.5 mg per kilogram body weight once daily is reasonable for patients without additional thrombosis risk(s) beyond that of APS. For patients with additional thrombosis risk factor(s), 0.5 mg per kilogram body weight every 12 hours would seem prudent.

The usual dose of HCQ dose is 400 mg per day.

Conditional recommendations generally reflect a lack of data, limited data, or conflicting data that lead to uncertainty.

Patients with APS with a history of thrombosis are commonly managed with long-term, oral anticoagulation.

In patients with obstetric APS without a history of thrombosis, the American College of Rheumatology conditionally recommends against treatment with IVIG or an increased LMWH dose, because these have not been demonstrably helpful in cases of pregnancy loss despite standard therapy with low-dose aspirin and prophylactic heparin or LMWH.

A particularly vexing clinical problem is the management of pregnancy in patients with APS with poor pregnancy outcomes despite treatment with heparin plus LDA, as had occurred in this patient. Best management of these so-called “refractory” obstetric cases is uncertain. Both American65 and European67 treatment guidelines recognize that glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, and intravenous immune globulin have been used in refractory cases, but the American guidelines recommend against the use of prednisone. Improved outcomes have been reported by 1 group using pravastatin.69 Finally, 1 retrospective study reported improved outcomes in a small series of women treated with tumor necrosis factor α blockade.70 Cautious interpretation of these studies is warranted - most of the data are retrospective and cases are heterogeneous in nature.23,71 Also, the outcomes of interest have not been compared to independently-ascertained patients matched for confounders known to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. In an ongoing treatment trial72 using anti–tumor necrosis factor α blockade in addition to standard treatment (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03152058), pregnancy outcomes are being compared with those of previously ascertained, prospectively observed patients receiving standard treatment.32

In patients meeting ACR/EULAR classification criteria for APS, undesired pregnancy or complications before fetal viability for which pregnancy continuation poses unacceptably high maternal risks are indications for pregnancy termination. Multidisciplinary management with hematology, rheumatology, maternal-fetal medicine, and obstetric anesthesiology is prudent.

Case 2A and 2B

Case 2A does not meet previous7,8 or ACR/EULAR1 APS classification criteria because she has low-positive aPL results. Case 2B meets previous classification criteria for APS (RPL and a moderate-positive aβ2GPI result). She does not, however, meet ACR/EULAR criteria, having no clinical criterion other than RPL (1 point) and an isolated moderate-positive IgM aβ2GPI (1 point). Such patients comprise a substantial proportion, if not a majority, of patients included in past treatment trials of patients with predominantly RPL and positive aPL results, typically trials comparing treatment with heparin plus LDA with LDA alone. Some of these trials found improved live birth rates with the combination of a thromboprophylactic-dose heparin plus LDA,73-76 and others did not.77,78 A systematic review highlighted the many limitations of the literature characterizing aPLs in the setting of RPL, including heterogeneity with regard to clinical events and laboratory criteria.17 A Cochrane database systematic review including 1295 pregnancies from 5 qualifying studies concluded treatment with a thromboprophylactic-dose heparin plus LDA vs LDA alone may increase the live birth rate (relative risk, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.49), but the characteristics of participants and adverse events were not uniformly reported, and the evidence was judged to be of low certainty.79

Although cases 2A and 2B do not meet ACR/EULAR classification criteria for APS, patients with a history of RPL in whom a possible diagnosis of APS has been suggested may be reluctant to forego treatment with a thromboprophylactic-dose LMWH plus LDA. Our approach is to first educate the patient about the derivation of, and rationale for, the international classification criteria, while reassuring her that the lack of a definite diagnosis of APS is favorable from a medical perspective. We then discuss the use of a thromboprophylactic-dose LMWH during pregnancy, noting that the need for such treatment is uncertain but that the attributable risk of serious antepartum bleeding is ≤1%.80-82 Finally, we outline the management options using the principles of shared decision making. These options include (1) discontinuing LMWH at the initial consultation, (2) discontinuing LMWH at some later point in the pregnancy when a successful pregnancy outcome seems likely to avoid the possible risk of excess bleeding if an obstetric intervention becomes necessary, or (3) continuing LMWH throughout the pregnancy under close clinical observation. We find most patients with RPL who feel they may have APS and are successfully pregnant on LMWH are unwilling to immediately discontinue it. Many will, however, consider discontinuing LMWH after a reassuring mid-trimester fetal ultrasound or at the beginning of the third trimester if the pregnancy is progressing normally. This approach is justified by the findings of a recent trial of thromboprophylactic LMWH in pregnancy in which the risk of a major antepartum bleed was low, but the risk was 3% to 4% in the immediate postpartum period.82

Case 3

Although initially thought to be a case of postpartum HELLP syndrome, case 3 was ultimately diagnosed as a TMA, possibly a forme fruste of CAPS, when her aPL results on day 5 were found to be triple-positive. Although the patient did not meet criteria for definite or probable CAPS because she had no histopathologic confirmation of small-vessel occlusion nor confirmatory testing for aPLs, the life-threatening nature of CAPS demands early recognition and treatment. High-quality treatment trials are lacking; thus, management of CAPS is based on expert opinion derived from case series.83-85 The recommended initial approach uses a combination of glucocorticoids, anticoagulation with heparin, and plasma exchange or intravenous immune globulin (Figure 3).86,87 Depending upon the nature of the case, eculizumab88 and rituximab89 could be considered in patients who respond poorly to initial treatments. Expert opinion suggests eculizumab in cases with prominent thrombotic microangiopathic features, and rituximab in cases with worsening thrombocytopenia without documented thrombosis as the most prominent clinical concern.

Algorithm for the management of CAPS during pregnancy (modified from Lim et al45). ∗Expert opinion suggests eculizumab in cases with prominent thrombotic microangiopathic features, and rituximab in cases with worsening thrombocytopenia without documented thrombosis as the most prominent clinical concern.

Algorithm for the management of CAPS during pregnancy (modified from Lim et al45). ∗Expert opinion suggests eculizumab in cases with prominent thrombotic microangiopathic features, and rituximab in cases with worsening thrombocytopenia without documented thrombosis as the most prominent clinical concern.

This patient was started on an unfractionated heparin drip and high-dose glucocorticoids, with dramatic improvement in her right upper quadrant pain over 12 hours. Therapeutic plasma exchange was started the following day. Within the next 3 days of treatment, her hematological parameters and hepatocellular enzymes normalized. In follow-up, triple-positive aPLs were confirmed.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the clinical and laboratory features of APS and the optimal treatment during pregnancy for APS are evolving. The ACR/EULAR classification criteria aim to enhance the specificity of the diagnosis of APS. For patients meeting these criteria, current guidelines for treatment in pregnancy are available. Yet, these patients should be counselled that they have an increased likelihood of adverse obstetric outcomes despite standard treatments. Patients whose only clinical criterion is RPL or fetal death in the absence of PreE and/or PI with severe features do not meet classification criteria for the diagnosis of APS, nor do patients with low-titer aCLs or aβ2GPIs or only IgM isotype antibodies. In such cases, clinicians should discuss management options that balance potential risks and benefits and engage patients in shared decision making. Finally, APS may present in pregnancy or postpartum as a TMA that initially mimics HELLP syndrome but requires a very different treatment approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Comstock and Karen Moser at the University of Utah, Department of Pathology for assistance in providing the placental histopathology photomicrograph for case 1 and the peripheral smear photomicrograph for case 3, respectively.

Authorship

Contribution: D.W.B. and M.Y.L. coauthored this article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.W.B. holds a research award from UCB Pharmaceuticals and is the James R. and Jo Scott Research Chair in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Utah. M.Y.L. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: D. Ware Branch, University of Utah Health Obstetrics and Gynecology, 30 North 1900 East, Room 2B200 SOM, Salt Lake City, UT 84132; email: ware.branch@hsc.utah.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal