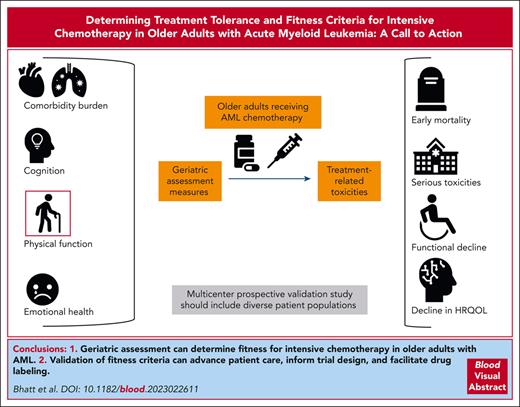

Visual Abstract

Determining fitness for intensive chemotherapy in an older adult with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an unanswered age-old question. Geriatric assessment captures any variation in multidimensional health, which can influence treatment tolerance. A prospective study is necessary to validate fitness criteria, determine whether geriatric assessment–based fitness performs superiorly to other criteria, and what components of geriatric assessment are associated with treatment tolerance. A validation study should enroll diverse patients from both academic and community centers and patients receiving intensive and lower-intensity chemotherapy. Geriatric assessment should include at minimum measures of comorbidity burden, cognition, physical function, and emotional health, which in previous smaller studies have shown to be associated with mortality in AML. These assessments should be completed before or within a few days of initiation of chemotherapy to reduce the influence of chemotherapy on the assessment results. Treatment tolerance has been measured by rates of toxicities in patients with solid malignancies; however, during the initial treatment of AML, rates of toxicities are very high regardless of treatment intensity. Early mortality, frequently used in previous studies, can provide a highly consequential and easily identifiable measure of treatment tolerance. The key end point to assess treatment tolerance, thus, should include early mortality. Other end points may include decline in function and quality of life and treatment modifications or cessation due to toxicities. Validating fitness criteria can guide treatment selection and supportive care interventions and are crucial to guide fitness-based trial eligibility, inform the interpretation of trial results, and facilitate drug labeling.

Introduction

Outcomes for older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remain suboptimal due to both poor disease biology and decreased resilience to the stresses of chemotherapy.1,2 A priority for improving outcomes in older adults is to validate criteria to inform fitness for intensive chemotherapy. Intensive chemotherapy with an anthracycline plus cyarabine (7 + 3) serves several important roles including rapid control of disease in patients with hyperleukocytosis, extending survival and potentially offering cure in a subset of patients, and providing an effective treatment to achieve remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Establishing validated fitness screening criteria may identify patients who are most likely to tolerate and benefit from intensive approaches as well as those who may benefit from specific interventions to enhance resilience. Overall, such criteria could contribute to the goal of identifying tolerable and effective treatment options for a wider range of older adults. Currently, there are no standardized set of fitness criteria that have been validated in a prospective fashion in multicenter studies. Without standard validated and reproducible measures, fitness determination is often made by physician estimation or age alone. Filling this gap in evidence is critical to guide evidence-based standards for treatment selection in clinical practice, for trial design, for interpretation of study results, and for drug labeling by regulatory agencies such as US Food and Drug Administration. Similarly, understanding which patients are more or less likely to tolerate and benefit from specific treatments cannot be optimally determined without characterization of the patient population studied. Therefore, defining and validating fitness criteria are critical to the long-term success of the precision oncology approach in older adults with AML and represents an unmet need in clinical practice.

Current standard of defining fitness for intensive chemotherapy

Older adults with AML vary in terms of their comorbidity burden, cognition, physical function, and emotional health, which can influence treatment tolerance as well as mortality.3-7 Traditionally, oncology trials including those that use Ferrara8 or other criteria have not routinely captured these measures. Instead, trials have relied on age, performance status, and comorbidity, which do not accurately capture multidimensional health and fitness of older adults. For example, older age alone is associated with higher early mortality as shown in an analysis of 3365 adults (aged 18-89 years) treated on intensive therapy protocols. However, in multicomponent modeling, chronologic age contributed only minimally to prediction of early mortality.9 In studies restricted to older adults that include assessment of comorbidity or function, chronologic age often loses its association with mortality, suggesting that typically unmeasured characteristics may better characterize fitness and explain the variability in outcomes among older adults.3,7 Geriatric assessment studies have demonstrated impairments in patients felt to have good performance status, highlighting the limitation of performance status assessment and importance of capturing multidimensional measures of fitness.3

Consensus-based Ferrara criteria exist8 and have been used in several clinical trials to identify patients who are less likely to tolerate intensive therapy. However, Ferrara criteria are based on age and comorbidities and lack multidimensional measure of fitness (Table 1). The utility of these criteria have not been validated prospectively but has been examined using retrospective data.10,11 One single-center study included heterogeneous group of patients with either newly diagnosed or relapsed or refractory AML or myelodysplastic syndrome and had received intensive chemotherapy. The study demonstrated differences in mortality among patients who were considered fit vs unfit.10 Several other approaches, which are not routinely used in clinical trials yet, have been used to determine the tolerance of intensive chemotherapy. All these studies use early mortality or survival as primary end point to measure treatment tolerance.

Approaches to determining tolerance of intensive chemotherapy treatment

| Approach . | Characteristics . | Evidence . | Nature of the study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geriatric assessment | Multidimensional assessment | Cognition, physical function, emotional health, and comorbidity burden correlate with mortality | Single-center and small multicenter prospective studies3,5,7 |

| Ferrara criteria | Mostly age, comorbidities, and ECOG PS | Criteria-defined fitness correlates with mortality | Retrospective studies10,11 |

| Comorbidity Index | Mostly comorbidities | Higher comorbidity burden correlates with mortality | Retrospective and prospective studies12 |

| Mortality scores∗ (several) | Age, performance status, laboratory data, etc | Higher score correlates with mortality | Post hoc analysis of trials and retrospective studies9,13-15 |

| Approach . | Characteristics . | Evidence . | Nature of the study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geriatric assessment | Multidimensional assessment | Cognition, physical function, emotional health, and comorbidity burden correlate with mortality | Single-center and small multicenter prospective studies3,5,7 |

| Ferrara criteria | Mostly age, comorbidities, and ECOG PS | Criteria-defined fitness correlates with mortality | Retrospective studies10,11 |

| Comorbidity Index | Mostly comorbidities | Higher comorbidity burden correlates with mortality | Retrospective and prospective studies12 |

| Mortality scores∗ (several) | Age, performance status, laboratory data, etc | Higher score correlates with mortality | Post hoc analysis of trials and retrospective studies9,13-15 |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

These scoring systems do not directly measure fitness but provide the risk of early mortality associated with the use of intensive chemotherapy.

Geriatric assessment as a measure of fitness for chemotherapy

Multiple studies in solid tumors and hematologic malignancies have demonstrated the utility of geriatric assessment in determining treatment tolerance.16-18 These studies have shown that the use of geriatric assessment data can guide personalized treatment selection based on the risk of toxicities and have informed management through supportive care interventions. Recently, randomized trials testing geriatric assessment with management interventions have shown that this approach decreases chemotherapy toxicity, lowers hospitalization risk, improves satisfaction with care, and may enhance quality of life.18-22 Although the majority of patients enrolled on these practice-changing randomized trials were patients with solid tumor, there was sufficient inclusion of patients with hematologic malignancies to support a broad guideline recommendation to perform geriatric assessment before the initiation of systemic cancer therapy for those aged ≥65 years.18

In AML, geriatric assessment measures can identify health impairments even in older adults with good performance status3 and may improve fitness determination and prognostication beyond what can be determined based on leukemia biology and AML risk categories.3,7 Specifically, measures of physical function, cognition, comorbidity burden, and emotional health are associated with risk of mortality in older adults with AML treated with intensive chemotherapy and lower-intensity chemotherapy.3-5,7 For these reasons, geriatric assessment may provide more sensitive and specific measures of fitness than other criteria. Validation of geriatric measures of treatment tolerance or mortality will provide strong rationale to conduct supportive care interventional studies and treatment assignment trials,6 similar to what has been done in solid malignancies. A key barrier to validating geriatric assessment in older adults with AML has been lack of funding support to pursue a validation study. The funding agencies have historically favored supporting an AML study that uses validated measures, rather than funding a validation study. However, without funding to validate geriatric assessment in a prospective multicenter study, validated fitness measures do not exist. This catch-22 situation has precluded robust validation and subsequent incorporation of geriatric assessment in AML trials and clinical practice.

Feasibility of conducting geriatric assessment in multicenter studies

Prior single-institution and small multicenter studies demonstrate the feasibility of performing geriatric assessment at the time of diagnosis of AML before initiation of treatment.3-5,7 Specifically, 2 prior Alliance trials have demonstrated that geriatric assessment measures can be captured in multicenter National Clinical Trial Networks Trials.4,5 Recruitment rates were high (80%) even in the intensive setting.4 The study measures are expected to take about 30 minutes to complete and include surveys, an assessment of gait speed, and a brief cognition screen. These measures were shown not to be significantly burdensome for patients or research personnel. Specifically, research staff reported no difficulty with geriatric assessment procedures at the time of AML diagnosis, and the majority of patients were satisfied with the length of the geriatric assessment (89%).4 These experiences highlight that geriatric assessment validation can be performed as a “companion” study, that is, by including geriatric assessments to ongoing therapeutic clinical trials. This will allow for a validation study to be completed without incurring excessive costs.

Research design considerations to validate fitness criteria

A prospective multicenter study is necessary to rigorously validate fitness criteria, determine whether geriatric assessment–based fitness performs superiorly to other criteria, and to determine which components of geriatric assessment are associated with treatment tolerance (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website). The treatment landscape for AML is evolving with varying intensity of treatment options such as traditional anthracycline and cytarabine based (7 + 3) chemotherapy, or lower-intensity chemotherapy with a hypomethylating agents in combination with venetoclax or a molecularly targeted agent, and emerging triplet regimens that add a third drug to lower-intensity chemotherapy. The fitness for treatment is dependent on the treatment context and is likely to differ based on the varying intensity of treatment. Therefore, a validation study should include cohorts of patients receiving different intensities of chemotherapy. The study design and sample size should allow for one to predict the fitness for intensive chemotherapy vs lower-intensity chemotherapy. Additionally, the study may identify patients who are at high risk of morbidity and mortality for even lower-intensity chemotherapy. To reach these goals, a core set of candidate geriatric assessments measures have to be consistently used across clinical trials of intensive and lower-intensity chemotherapy.23

The study should have broad eligibility criteria, enroll diverse patients including patients from both academic and community centers, and patients receiving intensive and lower-intensity chemotherapy. Geriatric assessment should include at minimum comorbidity burden (eg, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index), self-reported physical function (eg, instrumental activities of daily living), objective physical function (eg, gait speed or short physical performance battery), cognitive function (eg, Blessed orientation-memory-concentration test), and emotional health assessment (eg, geriatric depression scale). The recommendation to include these measures are based on the association between these measures and mortality in prior single-center and small multicenter studies in AML (Table 2).3-5,7 These assessments should be completed ideally before or within a few days after initiation of chemotherapy.

Pivotal prospective geriatric assessment studies in patients with AML

| Study . | Multicenter . | Prospective . | Intensive chemotherapy . | Predictor of mortality . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klepin et al3 | No | Yes | Yes | Objective physical function (SPPB < 9) and cognition (3MS < 77) |

| Klepin et al,4 CALGB 361006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | None (small feasibility study)∗ |

| Min et al7 | No | Yes | Yes | Objective physical function (SPPB < 9; 4-m gait speed < 4.82 s; and impaired sit to stand speed >11.2 s), emotional health (GDS ≥ 6) |

| Ritchie et al,5 CALGB | Yes | Yes | No | Comorbidity burden (HCT CI ≥ 3), cognition (BOMC ≥ 4), physical function (OARS IADL < 14) |

| Deschler et al24 | Yes | Yes | Various intensity treatments including BSC | Physical function (impaired ADL), high level of fatigue, and KPS < 80 |

| Study . | Multicenter . | Prospective . | Intensive chemotherapy . | Predictor of mortality . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klepin et al3 | No | Yes | Yes | Objective physical function (SPPB < 9) and cognition (3MS < 77) |

| Klepin et al,4 CALGB 361006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | None (small feasibility study)∗ |

| Min et al7 | No | Yes | Yes | Objective physical function (SPPB < 9; 4-m gait speed < 4.82 s; and impaired sit to stand speed >11.2 s), emotional health (GDS ≥ 6) |

| Ritchie et al,5 CALGB | Yes | Yes | No | Comorbidity burden (HCT CI ≥ 3), cognition (BOMC ≥ 4), physical function (OARS IADL < 14) |

| Deschler et al24 | Yes | Yes | Various intensity treatments including BSC | Physical function (impaired ADL), high level of fatigue, and KPS < 80 |

ADL, activities of daily living; BOMC, Blessed orientation-memory-concentration test; GDS, geriatric depression scale; HCT CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; 3MS, modified mini-mental state examination; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services; SPPB, short physical performance battery.

Min et al7 also demonstrated an association between impairment in function and outcomes such as nonrelapse mortality, grade 3 to 4 infections, and acute kidney injury as well as prolonged hospitalization.

A subsequent analysis of Klepin et al3 study demonstrated that objectively measured physical function (SPPB) and depressive symptoms are associated with worse survival in patients with AML undergoing postremission therapy.25

This feasibility study (n = 54) demonstrated that multidimensional geriatric study can be conducted across multicenter studies with high acceptance and requires ≤30 minutes in total for completion.

End point to assess treatment tolerance

The candidate end points to assess treatment tolerance include early mortality, rates of toxicities, decline in function and quality of life, treatment modifications or cessation due to toxicities, and time spent outside of home. Early mortality can provide a highly consequential and easily identifiable measure of treatment tolerance. Therefore, early mortality can be used as a robust primary end point, as has been done in multiple studies in the past.9,13-15 Early mortality can be the result of leukemia-related deaths in patients who do not respond to treatment, particularly if measured within 2 to 3 months after treatment initiation. Leukemia-related deaths may also be related to difficulty in maintaining treatment intensity as a result of intolerance in some patients. For these reasons, a statistical adjustment may be necessary to adjust for differences in the underlying disease biology (eg, as measured by Wheatley index26) that correlate with lack of response. The study should consider and account for confounding due to receipt of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Treatment tolerance and fitness for chemotherapy has been measured by rates of toxicities in patients with solid malignancies; however, during initial treatment of AML, rates of toxicities are very high regardless of treatment intensity. Among patients treated with a combination of azacitidine and venetoclax, grade ≥3 adverse events were noted in >95% of patients, and serious adverse events were noted in >80%.27 The high rates are due to hematologic toxicities and febrile neutropenia, which may not have a similar impact on survival and functional outcomes as other grade 3 to 4 toxicities such as grade 3 to 4 infections or organ toxicities. These factors have to be considered carefully if toxicities are included as an end point. Other outcomes may be suitable as secondary end points such as a decline in physical function,28 which may negatively affect survival in the intensive setting25 and can impair the completion of treatment.29 Conversely, reversible short-term toxicities and functional decline may be acceptable trade-off for achieving higher rates of remission or longer-term disease control.30 Longitudinal functional assessments that capture both shorter and longer-term changes, thus, can be meaningful from a patient perspective; many older adults consider such factors in making treatment decisions.30,31 Therefore, capturing longitudinal functional changes as secondary end points is valuable. Time spent outside of home (eg, in the hospital) is also meaningful in older adults32 and can be used as a secondary end point.

Impact of validating fitness criteria

Validating fitness criteria can advance patient care and trial science. Knowledge of risk of mortality and treatment tolerance can better inform patients of anticipated outcomes after treatment and facilitate advance care planning, as well as guide treatment selection and supportive care interventions in clinical practices. Validation of geriatric measures that are associated with early mortality will also provide a strong rationale for trials of supportive care interventions aimed at improving function. Prospectively validating fitness criteria in older adults with AML can enhance the goals of the precision oncology approach. Such criteria are also crucial to guide fitness-based trial eligibility, inform interpretation of trial results, and facilitate drug labeling by regulatory agencies. Fitness criteria can identify subgroups of unfit patients who are likely to not tolerate standard chemotherapy and benefit from early participation in clinical trials such as dose de-escalation studies or those testing novel less-toxic treatments. Equally important, validated fitness measures can identify those older adults who may be better served by more intensive treatment including a combination of intensive chemotherapy and novel agents to improve long-term outcomes and avoid undertreatment based on age and performance status. Such validated measures may also identify subgroups of patients where there is an equipoise to consider a randomized control trial comparing, for example, triplet lower-intensity regimen to a combination of intensive chemotherapy and novel agents. Although validating geriatric assessment can substantially change our current paradigm, not doing so will limit our ability to accurately determine fitness and personalize treatment selection based on the anticipated tolerance. Oncologists will continue to use their subjective perception of a patient’s fitness as a key factor in treatment selection. Given the impact of fitness on mortality, the medical community would continue to use a suboptimal approach to treatment selection, thus underserving older adults with AML. For all these reasons, validating fitness criteria is critical to improving outcomes of older adults with AML and advancing precision oncology approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank everyone at the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute who has been involved in discussing approaches to validate geriatric assessment in older adults with acute leukemias.

This study is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute under award numbers R37 CA276928 (V.R.B.) and R50 CA275927 (G.L.U.); and a grant from the NIH, National Institute on Aging under award number R33AG059206-03 (H.D.K.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors designed the concept; V.R.B. wrote the manuscript; and all authors critically reviewed and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.R.B. reports participating in Safety Monitoring Committee for Protagonist; serving as an associate editor for the journal Current Problems in Cancer, and as a contributor for BMJ Best Practice; receiving consulting fees from Imugene; research funding (institutional) from MEI Pharma, Actinium Pharmaceutical, Sanofi US Services, AbbVie, Pfizer, Incyte, Jazz, and National Marrow Donor Program; and drug support (institutional) from Chimerix for a trial. G.L.U. reports serving as a consultant for Jazz. H.D.K. reports receiving honoraria from UpToDate.

Correspondence: Vijaya Raj Bhatt, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 986840 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6840; email: vijaya.bhatt@unmc.edu.

References

Author notes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal