In this issue of Blood, Kenet et al1 report phase 3 trial results demonstrating safety and efficacy of once monthly fitusiran vs factor or bypassing agent (BPA) prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia without and with inhibitors, respectively.

Coagulation proceeds through either the intrinsic (factor VIIIa [FVIIa] to FIXa) or extrinsic (tissue factor, FVIIa) Xase to produce activated FX (FXa) and consequently thrombin. Hemophilia A and B result from a lack of either FVIII or FIX, respectively, and are treated by replacing the missing factor or, in the setting of antibodies to factors (“inhibitors”), bypassing the intrinsic Xase with prothrombinase complex concentrates or FVIIa (see figure). Standard of care in hemophilia is prophylactic therapy to eliminate the bleeding phenotype.2 Clotting factors (CFCs) and BPA prophylaxis require intravenous access and although effective when implemented can be burdensome and rely on strict adherence. Novel subcutaneously administered nonfactor therapies (NFTs) are aimed at either mimicking FVIIIa or decreasing natural anticoagulants to “rebalance” the system toward hemostasis.3 Although FVIIIa mimetics have greatly improved convenience and outcomes in patients with hemophilia A with and without inhibitors,4 persons with hemophilia B especially with inhibitors remain without alternatives to intravenous therapies. The advantage of rebalancing agents is that they are agnostic to hemophilia type and unaffected by the presence of factor inhibitors. Additionally, they carry the risk of unregulated procoagulant activity and thus can put certain patient populations at risk for thrombosis, particularly when combined with hemostatic therapies. Indeed, NFT pipeline development has been marred by thrombotic events requiring vigilance and dose modification.4,5

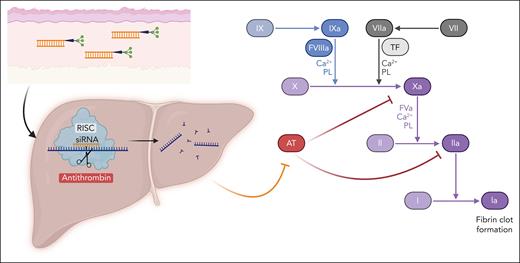

Fitusiran mechanism of action. Fitusiran is an siRNA therapeutic conjugated to N-acetylgalactosamine administered via subcutaneous injection. The conjugation to N-acetylgalactosamine enables binding to the asialoglycoprotein receptor, which is expressed exclusively on hepatocytes. Following entry into hepatocytes, fitusiran enters the RISC where it binds the complementary mRNA sequence of AT. This binding results in cleavage of AT mRNA resulting in potent and durable gene silencing. In coagulation, antithrombin serves as a natural brake to activated factor X (Xa) and thrombin (IIa), among other procoagulant factors. The decrease in antithrombin by fitusiran enables continued production of thrombin, resulting in increased fibrin and clot formation. AT, antithrombin; PL, phospholipid; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex; TF, tissue factor.

Fitusiran mechanism of action. Fitusiran is an siRNA therapeutic conjugated to N-acetylgalactosamine administered via subcutaneous injection. The conjugation to N-acetylgalactosamine enables binding to the asialoglycoprotein receptor, which is expressed exclusively on hepatocytes. Following entry into hepatocytes, fitusiran enters the RISC where it binds the complementary mRNA sequence of AT. This binding results in cleavage of AT mRNA resulting in potent and durable gene silencing. In coagulation, antithrombin serves as a natural brake to activated factor X (Xa) and thrombin (IIa), among other procoagulant factors. The decrease in antithrombin by fitusiran enables continued production of thrombin, resulting in increased fibrin and clot formation. AT, antithrombin; PL, phospholipid; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex; TF, tissue factor.

The rebalancing agent fitusiran is a novel, small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotide directed against antithrombin, a serine protease inhibitor produced in the liver that inhibits thrombin and FXa, in addition to other procoagulant factors (see figure).6 Preclinical studies demonstrated improved hemostasis in hemophilic conditions when antithrombin was lowered to ∼15% to 35% of normal.6 These data enabled initiation of phase 1 and 2 trials of fitusiran in 2015, which with a few interruptions have progressed to the current phase 3 trials. A report of a fatal cerebral sinus venous thrombotic event in the setting of CFC treatment for an initial misdiagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage in 2017 resulted in implementation of acute bleeding management guidelines and additional vigilance for thrombotic symptoms.7 Three phase 3 studies were initiated in 2018 including the current study (NCT03549871) and 2 studies comparing fitusiran to on-demand CFC (NCT03417245) or BPA (NCT03417102).

Kenet et al report findings from an open-label, multicenter trial comparing fitusiran to prophylactic BPA or CFC replacement in male subjects >12 years of age with severe hemophilia with and without inhibitors, respectively. The study included a 6-month lead-in with the prior prophylactic regimen followed by 6 months of fitusiran treatment. Fitusiran was initially dosed at 80 mg once monthly. Following a voluntary pause in 2020 due to reports of nonfatal thrombotic events (1 from the current study) in patients with antithrombin levels <10% to 20%, the dose was modified to 50 mg every 2 months to target antithrombin levels of 15% to 35%.7 All but 2 subjects in this study received 80 mg monthly; of note, 13 participants did not receive fitusiran for the entire 6 months, but 9 of 13 finished the study. The data are reported from 65 participants of whom 50 had hemophilia A and 19 had inhibitors. Mean antithrombin levels were 10% to 13% with peak thrombin values of 47 to 63 nM in the fitusiran treatment period. The primary end point was annualized bleeding rate (ABR) with secondary end points of spontaneous ABR and joint ABR. In the study population, fitusiran prophylaxis was more effective than BPA (median ABR 0 vs 6.5) and CFC replacement (median ABR 0 vs 4.4) therapy, corresponding to decreases in mean ABR of 79.7% and 46.4%, respectively. Spontaneous and joint ABR rates decreased by 55.6% and 51.5%, respectively. No treated bleeds were reported in 63.1% of fitusiran-treated subjects compared with 16.9% in the control group. Patients on inhibitors had more significant improvements in all ABR outcomes compared to patients without inhibitors, with secondary end points not reaching statistical significance in the noninhibitor cohort.

Approximately 70% of patients experienced an adverse event during fitusiran prophylaxis, and 9 subjects (13.4%) experienced a serious adverse event with 3 related to fitusiran (cerebrovascular event, pancreatitis, and cholelithiasis). Increased alanine aminotransferase (>3× upper limit normal in 25.4%), cholecystitis (7.5%), and cholelithiasis (7.5%) were reported in subjects without risk factors. The transaminase elevations resolved within 2 to 3 months but resulted in dose interruption in 9% of participants. The underlying mechanism of these liver-related adverse events is unclear though liver toxicity has been reported in other siRNA therapies. A trend toward increased D-dimer and prothrombin 1 + 2 fragments are reported, and 2 subjects experienced thrombotic events. A 37-year-old with prior undisclosed history of deep venous thrombosis (exclusion criteria) and thrombotic risk factors developed a right middle cerebral artery infarct with hemorrhagic transformation following treatment with FVIII for a spontaneous bleed resulting in discontinuation of fitusiran treatment. A 56-year-old man with no prior thrombotic history, risk factors, or factor exposure had a suspected thrombosis on papilla of the left eye. This occurred during the postfitusiran follow-up period without definitive thrombus identified by imaging. Both participants had antithrombin levels <13% during fitusiran treatment.

Antithrombin deficiency is a known potent hypercoagulable state.8 Although patients with hemophilia should seem to be protected from thrombotic events, studies are not clear that the prevalence of arterial or venous thrombosis are lower compared with the general population.9 The risk of thrombosis with NFTs, especially when combined with hemostatic agents or other thrombotic risk factors, is also reported with concizumab5 and emicizumab.4 In real-world analysis, the thrombotic adverse event rate of emicizumab may be higher than FVIII replacement.10 The efficacy of fitusiran is similar to these products with a dosing interval that may reduce treatment burden. However, risk mitigation strategies, including exclusion of patients with prior thrombotic events, will be necessary in ongoing risk-benefit analyses of fitusiran therapy. Indeed, ongoing trials are probing dose modifications that will hopefully help address this concern further. Ultimately, these additional data will inform shared decision-making between providers and persons with hemophilia on the ideal candidates for fitusiran therapy. Of note the hemophilia B community will likely welcome a highly effective subcutaneous treatment option.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.F.S. has received honoraria and participated in an advisory board from Sanofi/Sobi and Genentech/Roche. B.S.D. declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal