UM171 mediates concomitant CoREST/MYC degradation, which requires CUL3KBTBD4 ubiquitin ligase activation.

Forced expression of MYC abolishes UM171-mediated HSC expansion and multilineage potential.

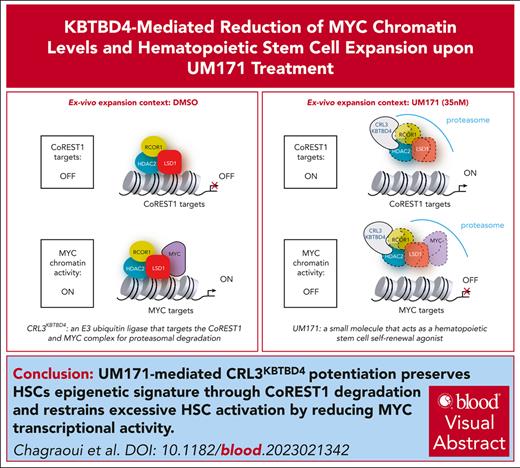

Visual Abstract

Ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is gaining importance for cell and gene therapy, and requires a shift from dormancy state to activation and cycling. However, abnormal or excessive HSC activation results in reduced self-renewal ability and increased propensity for myeloid-biased differentiation. We now report that activation of the E3 ligase complex CRL3KBTBD4 by UM171 not only induces epigenetic changes through CoREST1 degradation but also controls chromatin-bound master regulator of cell cycle entry and proliferative metabolism (MYC) levels to prevent excessive activation and maintain lympho-myeloid potential of expanded populations. Furthermore, reconstitution activity and multipotency of UM171-treated HSCs are specifically compromised when MYC levels are experimentally increased despite degradation of CoREST1.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) expansion appears helpful in the context of cord blood (CB) transplantation and gene editing/therapy.1 One of the most challenging aspects of ex vivo HSC expansion is to increase the number of HSCs while preserving their self-renewal and regenerative capacity.

Reminiscent in many ways of what is observed during aging, ex vivo culture systems engender replicative and metabolic stress that drive genetic and epigenetic alterations, ultimately resulting in HSCs functional decline. A more comprehensive understanding of the molecular requirements for engineering healthy HSCs would greatly improve our ability to expand them without limiting their repopulating capacity and would be critical for future therapeutically relevant HSC manipulation.

We recently showed that the small molecule UM171 activates the CRL3KBTBD4 E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets components of the CoREST1 complex for proteasomal degradation.2 Accordingly, this mechanism of action maintains the epigenetic landscape required to preserve HSC properties upon ex vivo cultures.2 Several stem-cell associated genes, including endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR), are upregulated by UM171-induced CoREST1 degradation and are essential for enhanced HSC activity. We also noticed that UM171 treatment is accompanied by a reduction in proliferation and metabolic activity of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).3 The molecular reason underlying this observation remains unclear.

Several studies have suggested that the regenerative, as well as the balanced lymphomyeloid repopulating capacity of HSCs, are inversely correlated to their divisional history.4-6 Slow-cycling HSCs (or dormant) adopt a distinct and reversible metabolic/epigenetic state that contributes to their longevity.7-9 Although dormant HSCs display low metabolic activity (ie, low levels of gene transcription, limited protein synthesis, and reduced mitochondrial activity), active HSCs exhibit high reactive oxygen species production, high proliferation rates, and instructive lineage priming.10 Dormant HSCs are also endowed with low intracellular calcium levels,11,12 high autophagic activity,13,14 and high lysosomal content.15 More recently, García-Prat et al showed that suppression of master regulator of cell cycle entry and proliferative metabolism (MYC) activity is coupled with enhanced transcription factor EB (TFEB)-associated lysosomal programs, which, in turn, favors self-renewal and limits HSC activation.16 Although the direct link between MYC and TFEB remains to be established, this program promotes lysosome content/turnover, hence clearance of CD71 from the membrane. Thus, CD71 surface expression is a surrogate for MYC/TFEB signaling; low levels of MYC correlates with high TFEB activity and high CD71 clearance. Moreover, Loeffler et al also provided new evidences that lysosome asymmetric inheritance correlates with asymmetric cosegregation of several stem cell markers (such as EPCR, CD71, CD34, and ITGA3), thus influencing human HSC fate ex vivo.17 Based on these recent findings, we hypothesized that MYC-TFEB activity and subsequent metabolic/mitogenic consequences are involved in UM171 mode of action.

Methods

Cell lines

OCI-AML1 were provided by the University Health Network (Toronto, Canada) and expanded in α minimal essential medium containing 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Shenandoah Biotechnology, Warminster, PA). The OCI-AML1 cell line was specifically chosen to dissect UM171 mode of action 2 because it shows a high clonogenicity and exhibits the most consistent response to UM171 regarding KBTBD4-dependent RCOR1 degradation. Dose-response curve of UM171-induced EPCR upregulation in OCI-AML1 cells indicate an 50% effective concentration of ∼100 nM. At optimal and nontoxic dose (250 nM), most OCI-AML1 cells respond to UM171 (CoREST1 degradation and subsequent upregulation of EPCR).

HEK-293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS. All cell lines were grown in humidified incubators at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Primary cell culture

This study was approved by the research ethics boards of the Université de Montréal and Charles LeMoyne Hospital (Greenfield Park, QC, Canada). All umbilical CB units were collected from consenting mothers at the Charles LeMoyne Hospital (Greenfield Park, QC, Canada). Human CD34+ CB cells were isolated using The EasySep positive selection kit (StemCell Technologies, catalog no. 18056). CB cells were cultured in HSC expansion media consisting of StemSpan (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with human 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (Shenandoah Biotechnology), 100 ng/mL FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Shenandoah Biotechnology), 50 ng/mL thrombopoietin (R&D Systems), and 50 ng/mL interleukin-6 (Shenandoah Biotechnology).

Animals and xenotransplantation

All animal procedures complied with recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and were approved by the Deontology Committee on Animal Experimentation at the University of Montreal.

For in vivo experiments presented in this study, NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ and NOD-Scid IL-2Rɣ243null 3/GM/SF (NSG and NSGS, respectively; The Jackson Laboratory) female mice bred in a pathogen-free animal facility were used. Briefly, cells were transplanted by tail vein injection into sublethally irradiated (250 cGy, <24 hours before transplantation) 8- to 10-week-old female NSG mice. NSG bone marrow cells were collected by femoral aspiration after 4, 8, and 16 weeks, or by flushing the 2 femurs, tibias, and hips when animals were euthanized at week 16. For all experiments, littermates of the same sex were randomly assigned to experimental groups. Mice were considered engrafted if human chimerism was >0.1%.

For secondary transplants, 50% of all the bone marrow cells harvested from primary mice were injected into a secondary sublethally irradiated NSG-SGM3 mouse. Bone marrow cells of the secondary mice were collected and analyzed 8 weeks after transplantation according to standard procedures.18,19

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) gating strategies to monitor human engraftment and lineage distribution in the bone marrow of transplanted animals are shown in supplemental Figure 12B, available on the Blood website.

Flow cytometry

Mouse anti-human antibodies were used to detect CD34 (APC or BV421; BD Biosciences), CD45RA (PE; BD Biosciences), CD86 (PerCP-eFluor710; eBioscience), CD90 (PECY7; BioLegend), EPCR (APC; BioLegend), and CD71 (FITC; Biolegend). Flow cytometry acquisitions were performed on a Canto II cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data analysis was performed using FowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) and GraphPad Prism software. Dead cells were excluded using 7-aminoactinomycin D staining. Gate strategies for FACS analysis of HSPC populations and for evaluation of human engraftment in the xenotransplantation model are included in supplemental Figure 12.

For intracellular staining, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pelleted, and fixed using True Nuclear fixation kit (BioLegend, catalog no. 424401). Cells were then stained with rabbit anti-RCOR1 (Novus Biologicals) or anti-rabbit MYC (Abcam), and FACS analysis was performed on a BD Biosciences Canto II cytometer.

Cellular translation rate analysis

Translation rate was measured by O-propargyl-puromycin (OP-PURO)-based translation assay kit (Cayman Chemicals). Briefly, cells pretreated with or without UM171 (250 nM) for 4 hours were then incubated for 30 minutes in the presence or absence of OP-PURO (50 μM) in culture medium at 37°C. Labeled cells were then washed, fixed, and permeabilized. Detection of OP-PURO was then performed using the Click-iT Plus Alexa Fluor 488 picolyl azide toolkit (Molecular Probes C10641), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lysotracker labeling

Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in StemSpan media supplemented with cytokines with LysoTracker Green (75 nM). After staining, cells were washed once and resuspended in PBS with 2.5% FBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cellular transcription rate analysis

Cells pretreated with or without UM171 (250 nM) for 4 hours were then incubated for 1 hour in the presence or absence of 1 mM 5-ethynyl-uridine (EU, Molecular Probes E10345) at 37°C. Cells were then rinsed in cold PBS and fixed and permeabilized (3.7% paraformaldehyde; 1 mM MgCl2; 125 mM pipes, pH8; 10 mM EGTA; and 0.2% Triton). Detection of EU was then performed using the Click-iT Plus Alexa Fluor 488 picolyl azide toolkit (Molecular Probes C10641).

Additional methods

All additional methods are provided in supplemental Text and Figures.

Results

Ex vivo expanded HSCs require KBTBD4 for long-term activity in vivo

Previously, we identified KBTBD4 as a cullin-3 adapter that targets members of the CoREST1 complex for proteasomal degradation upon UM171 exposure, thus leading to ex vivo expansion of phenotypical HSCs (as previously reported,2 and shown in supplemental Figure 1A). We now demonstrate that although KBTBD4 is dispensable for in vivo activity of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-expanded HSCs (see black dots in supplemental Figure 1B), it is critical for in vivo activity of UM171-expanded cells (supplemental Figure 1B red dots; supplemental Figure 1C). This data documents that all of UM171 activity depends on KBTBD4.

UM171 controls MYC-TFEB activity through KBTBD4

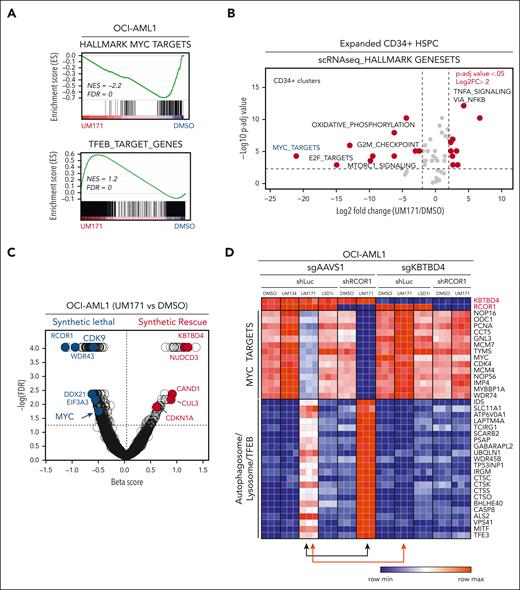

As expected from our previous work, gene set enrichment analysis of OCI-AML1 cells exposed to UM171 pointed to LSD1/CoREST1 reduced activity (see KDM1A [LSD1] in supplemental Figure 2A). Other gene set enrichment analysis signatures converge on MYC modulation including MYC itself (Figure 1A, upper panel), TFEB (Figure 1A, lower panel), cell cycle (eg, E2F targets), lysosome signaling, and translation, among others (supplemental Figure 2B-G).

UM171 exposure elicits a CRL3KBTBD4-dependent reduction of MYC transcriptional activity. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis showing MYC-associated (upper panel) and TFEB-associated (lower panel) gene signatures in OCI-AML1 cell line after exposure to UM171 (250 nM, 24 hours). (B) Gene set enrichment analysis performed on single-cell RNA sequencing show differentially regulated pathways in CB-derived CD34+ subsets after 7 days expansion in presence of UM171 (35 nM) vs vehicle (DMSO). (C) Genome wide CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9 knockout screen identified in addition to RCOR1,2 MYC, and its associated regulator CDK9 as synthetic lethal targets of UM171 in OCI-AML1 cell line. (D) Heat map showing transcriptomic expression of MYC (top) and TFEB (bottom) downstream targets upon exposure of DMSO (vehicle), UM134 (inactive analog of UM171, 250 nM), UM171 (250 nM), or LSD1 inhibitor (TCP, 10 μM) in the indicated group (sgAAVS1/shLuc, sgAAVS1/shRCOR1, sgKBTBD4/shLuc, and sgKBTBD4/shRCOR1). See also supplemental Figures 2 and 3. sg, single guide (RNA); sh, short hairpin (RNA).

UM171 exposure elicits a CRL3KBTBD4-dependent reduction of MYC transcriptional activity. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis showing MYC-associated (upper panel) and TFEB-associated (lower panel) gene signatures in OCI-AML1 cell line after exposure to UM171 (250 nM, 24 hours). (B) Gene set enrichment analysis performed on single-cell RNA sequencing show differentially regulated pathways in CB-derived CD34+ subsets after 7 days expansion in presence of UM171 (35 nM) vs vehicle (DMSO). (C) Genome wide CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9 knockout screen identified in addition to RCOR1,2 MYC, and its associated regulator CDK9 as synthetic lethal targets of UM171 in OCI-AML1 cell line. (D) Heat map showing transcriptomic expression of MYC (top) and TFEB (bottom) downstream targets upon exposure of DMSO (vehicle), UM134 (inactive analog of UM171, 250 nM), UM171 (250 nM), or LSD1 inhibitor (TCP, 10 μM) in the indicated group (sgAAVS1/shLuc, sgAAVS1/shRCOR1, sgKBTBD4/shLuc, and sgKBTBD4/shRCOR1). See also supplemental Figures 2 and 3. sg, single guide (RNA); sh, short hairpin (RNA).

Single-cell RNA sequencing of day 7–expanded CD34+ CB-derived cells demonstrated the high abundance of primitive CD34+ cell types in UM171 condition as compared with DMSO-treated culture (supplemental Figure 3A-C). These UM171-expanded CD34+ cells also show repression of MYC-associated gene signatures (Figure 1B). Specifically, although E2F and MYC signatures are low in unmanipulated CD34+ CB cells, these programs are increased upon ex vivo culture in both total and HLF-expressing (HSC-enriched) cells (supplemental Figure 3D-F, blue vs black violin plots). Hence, MYC-E2F activity is significantly attenuated in the presence of UM171 (supplemental Figure 3D-F, red violin plots). Consistently, cell cycle scoring analysis clearly demonstrates an enrichment of cells in G1 phase upon UM171 treatment in total and HSC-enriched subsets (supplemental Figure 3G-H).

In line with these observations, we showed, by genome-wide CRISPR screen, that loss of MYC, or its well-known regulator CDK9, is synthetic lethal with UM171 treatment (see arrow in Figure 1C).

Consistent with a MYC-directed suppression of TFEB, we found that UM171 exposure leads to an induction of TFEB/lysosome targets (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 2G). The UM171-induced regulation of MYC/TFEB is lost in the absence of KBTBD4 (see Figure 1D, red arrow) and not affected by chemical inhibition of LSD1 (LSD1i in Figure 1D). Reduction of RCOR1 levels, by short hairpin RNA, strongly enhanced UM171-induced MYC and TFEB signatures (black arrow in Figure 1D).

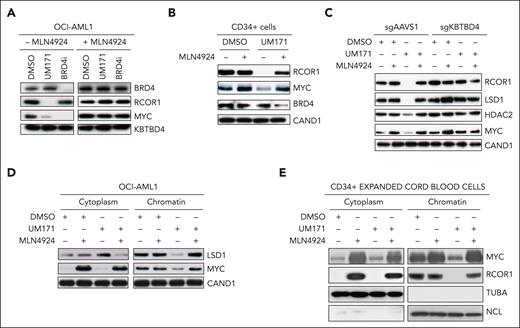

UM171 promotes reduction of chromatin-bound MYC protein

Consistent with the strong MYC transcriptional signature (Figure 1), UM171 treatment rapidly (4 hours) results in a significant reduction of MYC protein levels both in OCI-AML1 (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 4A) and CD34+ CB cells (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 4B). In contrast to BRD4 inhibitor mode of action, UM171-mediated MYC reduction does not occur through BRD4 degradation (Figure 2A).

UM171 targets chromatin-bound MYC for degradation in a CRL3KBTBD4 dependent manner. (A) Western blot analysis of total proteins extracted from OCI-AML1 cells exposed to DMSO, UM171 (250 nM), or BRD4 inhibitor ARV771 (1 μM) in presence or absence of the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 (1 μM) for 4 hours. Representative blots showing BRD4, RCOR1, MYC, and KBTBD4 (loading control) protein levels. (B) Western blot analysis of total proteins extracted from day 3–expanded CD34+ CB cells exposed to DMSO, UM171, DMSO/MLN4924, or UM171/MLN4924 for 4 hours. Representative blot showing RCOR1, MYC, BRD4, and CAND1 (loading control) protein levels. (C) Western blot analysis of total proteins extracted from sgAAVS1- or sgKBTBD4-engineered OCI-AML1 cells exposed to DMSO or UM171 (250 nM) for 4 hours, with or without MLN4924 (1 μM). Representative blots showing RCOR1, LSD1, HDAC2, MYC, and CAND1 (loading control) protein levels. (D) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic vs chromatin bound proteins extracted from OCI-AML1 exposed to DMSO or UM171 (250 nM) for 1 hour with or without MLN4924 (1 μM). Representative blots showing LSD1, MYC, and CAND1 (loading control) protein levels. (E) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic vs chromatin-bound proteins extracted from day 3–expanded CD34+ CB cells exposed to DMSO, UM171, DMSO/MLN4924, or UM171/MLN4924 for 4 hours. Representative blots showing MYC, RCOR1, TUBA, and NCL (loading controls) protein levels. See also supplemental Figure 4 for quantitative analysis of MYC protein levels.

UM171 targets chromatin-bound MYC for degradation in a CRL3KBTBD4 dependent manner. (A) Western blot analysis of total proteins extracted from OCI-AML1 cells exposed to DMSO, UM171 (250 nM), or BRD4 inhibitor ARV771 (1 μM) in presence or absence of the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 (1 μM) for 4 hours. Representative blots showing BRD4, RCOR1, MYC, and KBTBD4 (loading control) protein levels. (B) Western blot analysis of total proteins extracted from day 3–expanded CD34+ CB cells exposed to DMSO, UM171, DMSO/MLN4924, or UM171/MLN4924 for 4 hours. Representative blot showing RCOR1, MYC, BRD4, and CAND1 (loading control) protein levels. (C) Western blot analysis of total proteins extracted from sgAAVS1- or sgKBTBD4-engineered OCI-AML1 cells exposed to DMSO or UM171 (250 nM) for 4 hours, with or without MLN4924 (1 μM). Representative blots showing RCOR1, LSD1, HDAC2, MYC, and CAND1 (loading control) protein levels. (D) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic vs chromatin bound proteins extracted from OCI-AML1 exposed to DMSO or UM171 (250 nM) for 1 hour with or without MLN4924 (1 μM). Representative blots showing LSD1, MYC, and CAND1 (loading control) protein levels. (E) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic vs chromatin-bound proteins extracted from day 3–expanded CD34+ CB cells exposed to DMSO, UM171, DMSO/MLN4924, or UM171/MLN4924 for 4 hours. Representative blots showing MYC, RCOR1, TUBA, and NCL (loading controls) protein levels. See also supplemental Figure 4 for quantitative analysis of MYC protein levels.

MYC protein levels are unaffected if UM171-treated cells are exposed to the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 (Figure 2A-C; supplemental Figure 4A-C). Likewise, KBTBD4 is required for UM171-induced MYC reduction (Figure 2C, compare lane 3 to lane 7; supplemental Figure 4C).

Chromatin and cytoplasmic extracts further revealed that UM171-induced reduction of MYC was only observed in the chromatin compartment (Figure 2D for OCI-AML1 and 2E for primary CD34+ cells; and supplemental Figure 4D-E). Interestingly, MLN4924 treatment elevates MYC steady-state levels in the cytoplasm, consistent with a rapid turnover in this compartment (Figure 2D-E, compare first lane with second lane in cytoplasmic fraction; supplemental Figure 4D). In contrast, chromatin-bound MYC fractions are mainly unaffected by neddylation inhibition, suggestive of a low turnover rate (Figure 2D-E, compare first lane with second lane in chromatin fraction; supplemental Figure 4D-E). MLN4924 treatment restored chromatin MYC (Figure 2D, compare third lane with fourth lane in right panel; supplemental Figure 4D-E), indicating that UM171 promotes neddylation-dependent reduction of MYC specifically at the chromatin.

UM171 affects transcription, translation rates, and lysosome content

Considering the role of MYC in regulating global transcription and translation, we evaluated the effect of UM171 on RNA and protein synthesis. We observed a significant KBTBD4-dependent reduction (∼30%) in EU labeling of nascent RNA upon UM171 treatment in OCI-AML1 cells (supplemental Figure 5A). Similarly, the rate of protein synthesis was decreased in UM171-exposed OCI-AML1 cells in a KBTBD4-dependent manner (supplemental Figure 5B). Again, this observation was confirmed using CD34+ cells treated for 24 hours with UM171 (supplemental Figure 6A).

Next, we showed an increased lysosome content in CD34+ cells exposed to UM171 for 24 hours (supplemental Figure 6B). Remarkably, CD34hiCD45RAloCD90+ HSPC subsets (supplemental Figure 6C) generated after 7 days of culture in presence of UM171 also showed reduced translation rate and higher lysosome content when compared with DMSO controls (supplemental Figure 6D-E). Moreover, CD34+ cells produced at day 7 in presence of UM171 display reduced CD71 surface levels as compared with DMSO (supplemental Figure 6F-G).

UM171 promotes integrated stress response (ISR) in CD34+ cells

Considering the central role of the ISR in controlling global protein synthesis in HSCs upon stress,20 we evaluated the ISR-induced ATF4 translation in UM171- vs DMSO-expanded HSPCs (supplemental Figure 7). As expected, and independent of the treatment, HSCs (CD34+CD45RA−CD90+) enriched subsets showed more ISR activity than multipotent (CD34+CD45RAlo) progenitors (supplemental Figure 7B vs supplemental Figure 7A). Consistent with MYC/TFEB modulation, UM171 promotes higher ISR activity in both HSCs and multipotent progenitors as compared with DMSO (supplemental Figure 7A-C).

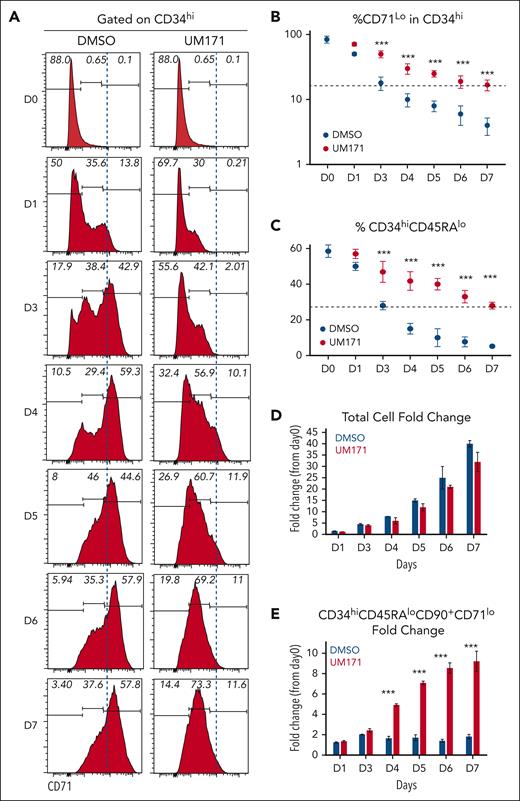

Reduced MYC activity in fresh and ex vivo expanded HSPCs

To further understand the relevance of MYC activity in UM171-induced HSPC expansion, we used CD71 surface expression as a proxy. In the DMSO control condition, CD71 expression gradually increases on the surface of CD34high cells, reaching the highest levels by day 3 to 4 (see Figure 3A, blue dashed line). UM171 treatment significantly slows down CD71 surface appearance on these cells, keeping its surface abundance relatively low throughout the culture period (right panels in Figure 3A). Notably, loss of CD34hiCD71lo cells coincides with decline in phenotypically defined (CD34hiCD45RAlo) HSPC subsets (Figure 3B-C). Importantly, although UM171 exposure does not dramatically alter total cell fold-change, it resulted in a ∼10-fold net expansion of CD34+CD45RAloCD90+CD71lo HSPC subset (Figure 3D-E, red bars). In contrast, this primitive population is at best maintained in DMSO condition (Figure 3E, blue bars).

Reduced CD71 surface expression coincides with ex vivo expansion of HSC subsets. (A) FACS profiles showing kinetics of CD71 surface expression (as proxy for MYC transcriptional activity) on CD34+ CB cells cultured for 7 days in presence of DMSO or UM171 (35 nM). (B) Percentage of CD71lo cells in CD34hi primitive subsets generated in DMSO or UM171 culture conditions over a 7-day culture period. (C) Percentage of CD34hi CD45RAlo primitive cells. (D) Bar graph showing total cell and (E) CD34hiCD45RAloCD90+CD71lo cells fold expansion over day 0 in the indicated group. Representative of 3 independent experiments (2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001).

Reduced CD71 surface expression coincides with ex vivo expansion of HSC subsets. (A) FACS profiles showing kinetics of CD71 surface expression (as proxy for MYC transcriptional activity) on CD34+ CB cells cultured for 7 days in presence of DMSO or UM171 (35 nM). (B) Percentage of CD71lo cells in CD34hi primitive subsets generated in DMSO or UM171 culture conditions over a 7-day culture period. (C) Percentage of CD34hi CD45RAlo primitive cells. (D) Bar graph showing total cell and (E) CD34hiCD45RAloCD90+CD71lo cells fold expansion over day 0 in the indicated group. Representative of 3 independent experiments (2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001).

CD71lo cells are enriched for long-term repopulating HSCs

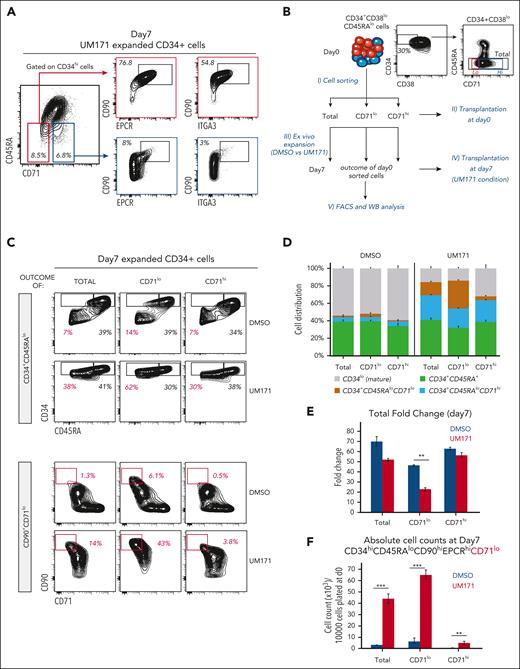

Further phenotypical characterization of UM171-expanded cells revealed that CD34+CD45RAloCD71lo cells (Figure 4A, red square) express higher levels of HSC markers (CD90/EPCR/ITGA3) than CD34+CD45RAloCD71hi cells (Figure 4A, blue square). To determine whether the relative abundance of CD71 can distinguish cells with high ex vivo and in vivo regenerative potential, we sorted CD71lo and CD71hi cell fractions from freshly thawed (uncultured) CD34+CD38loCD45RA− long-term HSCs (experimental design in Figure 4B). Noticeably, both CD71lo and CD71hi HSC fractions rapidly differentiated in control (DMSO) cultures (Figure 4C-D; supplemental Figure 8A, see predominance of CD34lo mature [Figure 4D] and CD34+CD45RA+ precursor cells [supplemental Figure 8A, middle panel]), resulting in a marginal production of primitive cell subsets (Figure 4C-D,F; supplemental Figure 8A, left and right panels). In sharp contrast, upon UM171 exposure, the CD71lo HSC fraction, although less proliferative (Figure 4E), retained primitive features and produced a ∼7-fold net expansion of the CD34+CD45RAloCD90hiEPCRhiCD71lo population (Figure 4C-F; supplemental Figure 8A-B). Interestingly, CD71hi cells, although still presenting some primitive characteristics in UM171 condition (see CD34+CD45RAlo and CD34+CD45RAloCD90hiEPCRhiCD71hi populations in supplemental Figure 8A), produced few primitive CD34+CD45RAloCD90hiEPCRhiCD71lo cells (Figure 4C-F; supplemental Figure 8A-C). Of note, only CD34+CD38loCD45RAloCD71lo cultured in the presence of UM171 show low nuclear MYC and LSD1 levels (supplemental Figure 8D, red square).

CD71 surface expression delineates distinct HSC-enriched subsets. (A) Representative FACS profiles showing percentage of CD45RAloCD71lo (red square) and CD45RAloCD71hi (blue square) subsets in CD34hi expanded cells and the expression of HSCs markers CD90, EPCR, and ITGA3 in these populations after 7 days culture in presence of UM171 (35 nM). (B) Schematic representation of the experimental design to determine the impact of CD71 levels on HSPC activity in fresh and ex vivo cultured CB cells. (C) Representative FACS profiles showing percentage of CD34+CD45RAlo, CD34+CD45RAhi, and CD90+CD71lo subsets in cultures initiated with total, CD71lo, and CD71hi sorted HSCs (CD34+CD38loCD45RAlo) populations and exposed to DMSO or UM171 (35 nM) for 7 days. (D) Cell lineage distribution in cultures initiated with total, CD71lo, and CD71hi sorted HSCs populations and exposed to DMSO or UM171 (35 nM) for 7 days. Bar graph showing total cell fold expansion (E) and absolute count of CD34hiCD45RAloCD90+EPCR+CD71lo HSC subset (F) in the indicated group. Representative of 3 independent experiments (2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001). See also supplemental Figures 8 and 9.

CD71 surface expression delineates distinct HSC-enriched subsets. (A) Representative FACS profiles showing percentage of CD45RAloCD71lo (red square) and CD45RAloCD71hi (blue square) subsets in CD34hi expanded cells and the expression of HSCs markers CD90, EPCR, and ITGA3 in these populations after 7 days culture in presence of UM171 (35 nM). (B) Schematic representation of the experimental design to determine the impact of CD71 levels on HSPC activity in fresh and ex vivo cultured CB cells. (C) Representative FACS profiles showing percentage of CD34+CD45RAlo, CD34+CD45RAhi, and CD90+CD71lo subsets in cultures initiated with total, CD71lo, and CD71hi sorted HSCs (CD34+CD38loCD45RAlo) populations and exposed to DMSO or UM171 (35 nM) for 7 days. (D) Cell lineage distribution in cultures initiated with total, CD71lo, and CD71hi sorted HSCs populations and exposed to DMSO or UM171 (35 nM) for 7 days. Bar graph showing total cell fold expansion (E) and absolute count of CD34hiCD45RAloCD90+EPCR+CD71lo HSC subset (F) in the indicated group. Representative of 3 independent experiments (2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001). See also supplemental Figures 8 and 9.

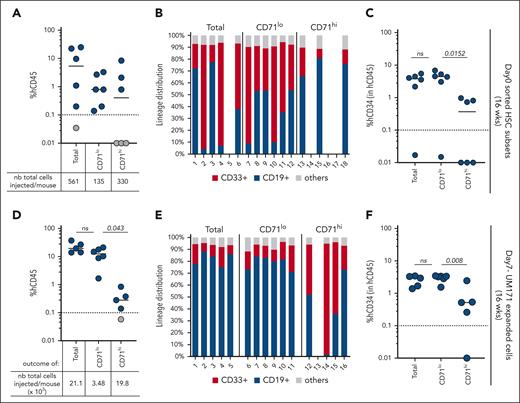

Next, we examined the long-term repopulating capacity of CD71lo and CD71hi HSCs (Figure 5A-C) and their respective UM171-expanded progeny (Figure 5D-F). Interestingly, both uncultured CD71lo and CD71hi HSCs exhibit long-term multilineage repopulating abilities (Figure 5A-B). However, although all CD71lo injected recipients were engrafted, CD71hi cells (although more numerous) failed to establish grafts in half of the recipients (Figure 5A, gray circle; Figure 5B). In addition, bone marrow from CD71lo-injected hosts presented higher frequencies in CD34+ primitive cells (Figure 5C).

CD71lo (ie, MYClo) HSCs exhibit enhanced long-term repopulation. Human CD45 engraftment (A), lineage potential (B), and percentage of human CD34+ primitive subsets (C) were assessed at 16 weeks after transplantation for each NSG mouse transplanted with the indicated fresh unexpanded HSCs subset. Human CD45 engraftment (D), lineage potential (E), and percentage of human CD34+ primitive subsets (F) were assessed at 16 weeks after transplantation for each NSG mouse transplanted with UM171-expanded CD71 subsets. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, not significant.

CD71lo (ie, MYClo) HSCs exhibit enhanced long-term repopulation. Human CD45 engraftment (A), lineage potential (B), and percentage of human CD34+ primitive subsets (C) were assessed at 16 weeks after transplantation for each NSG mouse transplanted with the indicated fresh unexpanded HSCs subset. Human CD45 engraftment (D), lineage potential (E), and percentage of human CD34+ primitive subsets (F) were assessed at 16 weeks after transplantation for each NSG mouse transplanted with UM171-expanded CD71 subsets. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, not significant.

The difference between CD71lo and CD71hi fractions became even more apparent after a 7-day culture with UM171 treatment (Figure 5D-F). Only CD71lo progeny yielded reconstitution levels comparable what that of the parental population (CD71lo and Total; Figure 5D), although ∼5-times less numerous. Accordingly, long-term multilineage reconstitution activity and CD34+ cell frequency were drastically attenuated for CD71hi progeny (Figure 5E-F).

To further evaluate the importance of CD71 expression on ex vivo expanded HSCs, we sorted CD71lo and CD71hi HSC-enriched populations at day 7 and further expanded them separately for an additional 7 days (day +14) at which time phenotypical analysis was conducted (supplemental Figure 9A). Once again, although CD34+CD45RAloCD71hi HSPCs rapidly differentiated (supplemental Figure 9B-D), CD34+CD45RAloCD71lo cells were of a more primitive phenotype and showed a much better proliferative potential (supplemental Figure 9B-D). Providing the hypothesis that CD71 is a reliable surrogate marker of MYC activity, these results suggest that MYC governs the degree to which HSPCs can be expanded while preserving adequate repopulating capacity.

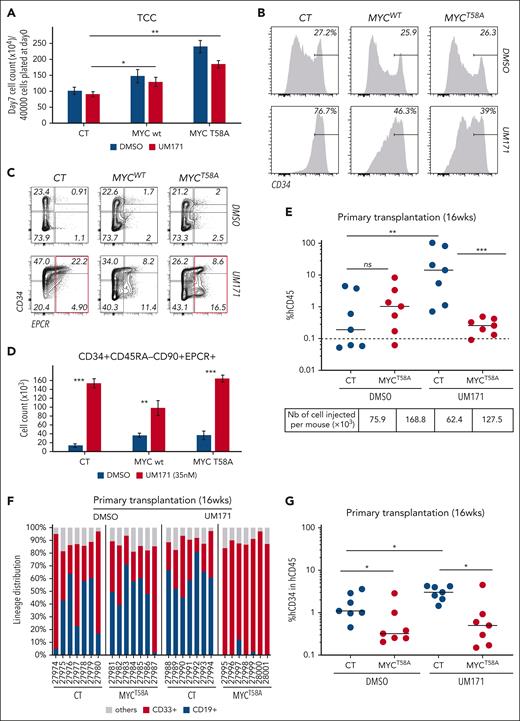

MYC deregulation affects UM171-induced HSCs expansion

To gain insights into the importance of reduced MYC levels in UM171-driven HSCs expansion, CD34+ cells were engineered to overexpress wild-type (WT) or degradation-resistant (T58A) MYC and expanded ex vivo in control or UM171-supplemented cultures (supplemental Figure 10A). Next, phenotypical and functional HSPCs were evaluated. Results indicate that MYCWT and MYCT58A overexpression led to enhanced proliferation in all conditions (Figure 6A). Higher MYC levels did not affect the proportion of CD34+ cells in control DMSO cultures (Figure 6B, upper panel; supplemental Figure 10B). In contrast, percentages of CD34+ cells were reduced in UM171-supplemented cultures (Figure 6B, lower panel; supplemental Figure 10B), indicating a context specific affect of MYC deregulation. Interestingly, MYCT58A overexpression did not prevent UM171-mediated overall induction of EPCR expression (Figure 6C, red square). Considering that EPCR is a target of CoREST1,2 these results suggest that MYC overexpression does not affect CoREST1 degradation. This hypothesis was also validated in OCI-AML1 cells (supplemental Figure 11; supplemental Text).

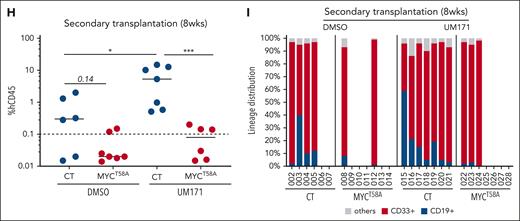

UM171-driven MYC degradation is essential for its activity on HSCs expansion. (A) Bar graph showing total cell counts after 7 days culture of control (CT), or MYCWT- or MYCT58A-transduced CD34+ cells in presence or absence of UM171 (35 nM). (B-C) Representative FACS profiles of CD34+ (B) and CD34+EPCR+ (C) subsets in CT or MYCWT- or MYCT58A-transduced CD34+ CB cells cultured for 7 days in presence of DMSO or UM171 (35 nM). (D) Absolute count of CD34+CD45RA−CD90+EPCR+ cell subset in the indicated group (CT, MYCWT, or MYCT58A) after 7 days in presence of DMSO or UM171 (35 nM). Representative of 4 independent experiments. Human CD45 engraftment (E), lineage potential (F), and percentage of human CD34+ primitive subsets (G) in primary NSG mice transplanted with ex vivo cultured CB cells from the indicated group (outcome of 2 competitive repopulation units) at 16 weeks after transplantation. Human CD45 engraftment (H) and lineage potential (I) in secondary NSG-SGM3 recipients at 8 weeks after transplantation (2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001). See also supplemental Figures 10 and 11.

UM171-driven MYC degradation is essential for its activity on HSCs expansion. (A) Bar graph showing total cell counts after 7 days culture of control (CT), or MYCWT- or MYCT58A-transduced CD34+ cells in presence or absence of UM171 (35 nM). (B-C) Representative FACS profiles of CD34+ (B) and CD34+EPCR+ (C) subsets in CT or MYCWT- or MYCT58A-transduced CD34+ CB cells cultured for 7 days in presence of DMSO or UM171 (35 nM). (D) Absolute count of CD34+CD45RA−CD90+EPCR+ cell subset in the indicated group (CT, MYCWT, or MYCT58A) after 7 days in presence of DMSO or UM171 (35 nM). Representative of 4 independent experiments. Human CD45 engraftment (E), lineage potential (F), and percentage of human CD34+ primitive subsets (G) in primary NSG mice transplanted with ex vivo cultured CB cells from the indicated group (outcome of 2 competitive repopulation units) at 16 weeks after transplantation. Human CD45 engraftment (H) and lineage potential (I) in secondary NSG-SGM3 recipients at 8 weeks after transplantation (2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001). See also supplemental Figures 10 and 11.

MYC-induced cell proliferation lead to a twofold to threefold increase in phenotypically primitive HSPCs in DMSO control cultures (blue histograms in Figure 6D). In contrast, and although the proportion of HSCs and progenitors are reduced (supplemental Figure 10B), MYCT58A overexpression did not affect the absolute counts of phenotypical HSCs (CD34+CD45RA−CD90+EPCR+) in cultures supplemented with UM171 (red histograms in Figure 6D). Notably, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester–based proliferation experiments showed that high MYC levels enhanced cell divisions in UM171-expanded CD34+EPCR+ HSCs (supplemental Figure 10C). Moreover, and consistent with MYC/TFEB impact on CD71 cell surface presentation, we found that MYCT58A overexpression prevented CD71 surface clearance in primitive CD34+ cells exposed to UM171 (supplemental Figure 10D). This potentially suggest that MYChi HSPCs are functionally compromised in vivo although more proliferative in vitro.

To test this hypothesis, MYCT58A-overexpressing CD34+ cells were expanded for 7 days in the presence or absence of UM171 and transplanted in NSG mice. Short-term (4 and 8 weeks; supplemental Figure 10E), and long-term (16 weeks; Figure 6E-G) reconstitution were subsequently assessed.

MYC overexpression did not significantly change human multilineage engraftment ability of cells expanded in DMSO cultures (Figure 6E-F; supplemental Figure 10E, compare DMSO-CT with DMSO-MYCT58A). However, it somewhat lowered the frequency of primitive CD34+ cells in the bone marrow of primary recipients (Figure 6G). Accordingly, DMSO-expanded MYChi cells failed to establish grafts in ∼70% of the secondary recipients (compared with ∼30% in control condition; Figure 6H-I). This data suggest that in control conditions, MYC overexpression perturbs the regenerative potential of HSPCs. In contrast, high MYC levels interfered with the ability of UM171 treatment to enhance reconstitution potential of treated cells. This was true for all time points examined in primary (4 and 8 weeks, supplemental Figure 10E; 16 weeks, Figure 6E) and secondary recipients (Figure 6H-I). Moreover, and akin to DMSO control cultures, CD34+ reconstitution was negatively affected by MYC overexpression (Figure 6G). Likewise, lymphoid differentiation appeared compromised by MYC overexpression in UM171 context, because thymic and B-cell reconstitutions were severely reduced at 16 weeks after transplantation in primary recipients (thymus, supplemental Figure 10F; bone marrow B cells, Figure 6F).

Discussion

In this study, we report that UM171 safeguards HSC fitness upon culture-mediated stress by tuning MYC-driven programs. We demonstrate that, in addition to promoting degradation of the CoREST1 complex2,21; or ELM2 domain–containing proteins,22 UM171 also rapidly induces reduction of chromatin-bound MYC. This reduction relies on the activation of CRL3KBTBD4 ubiquitin ligase, indicating that the adapter KBTBD4 acts upstream of both CoREST1 2 and MYC regulatory pathways. Interestingly, knockdown of RCOR1 results in a synergistic repression of MYC targets in the presence of UM171, providing more evidence of an interplay between MYC and CoREST1. In contrast MYC overexpression did not appear to modulate CoREST1-dependent target genes such as EPCR. In line with these observations, it was recently reported that LSD1 interacts directly with MYC on chromatin and promotes RNA polymerase II pausing at co-occupied promoters. The authors show that MYC recruitment to genes coregulated with LSD1 depends on LSD1.23 In contrast, LSD1 recruitment to MYC/LSD1 coregulated regions is independent of the presence of MYC.23 Consistent with LSD1 dependency of MYC genomic binding, Ecker et al showed that a vast majority of all identified MYC chromatin occupancy overlapped with binding of HDAC2 (another member of the LSD1/CoREST complex).24 Moreover, MYC binding to chromatin, and thus transcriptional activity, is significantly compromised upon HDAC2 inhibition.24 Adding a further level of complexity to this CoREST1/MYC relationship, LSD1 has been shown to destabilize FBXW7, a well-known MYC E3 ubiquitin ligase, in a demethylase-independent manner.25,26 Collectively, these findings strongly suggest that UM171-mediated MYC reduction ensues from LSD1/CoREST modulation.

MYC is involved in a wide range of cellular processes including cell-cycle control, metabolism, proteostasis, and self-renewal.27 Several studies have also pointed to a critical role of MYC dosage in HSC functions.28-30 In accordance with our results, Wilson et al demonstrated that Myc loss of function in mice resulted in an accumulation of HSCs, whereas a forced Myc expression triggered a loss of HSC self-renewal activity.31 Therefore, MYC acts as a molecular rheostat, controlling the balance between quiescence/self-renewal and activation/differentiation.

Consistent with suppression of MYC activity, we show that UM171 exposure causes a decrease in protein translation rate. Recent studies revealed that accumulation of misfolded proteins is associated with increased levels of MYC protein, particularly in HSCs.32 It has been proposed that HSCs depend on low rates of protein synthesis to maintain proteome quality and hence preserve their self-renewal properties.32,33 Of interest, both MYC-dependent 34-36 and independent 37 mechanisms have been identified to restrict protein synthesis and maintain HSC function integrity.

As mentioned earlier, age-related epigenetic and metabolic alterations of HSCs are strongly coupled with their proliferative capacity.38 The theory that HSCs can store information about their divisional history as a form of memory to control their regenerative and lineage priming capacity gains more and more support.39,40 Although the idea of an unlimited ex vivo HSC expansion is appealing, one should raise concern that activated HSCs might lose their ability to return to a dormant status, permanently restricting their regenerative capacity, once they have crossed a certain threshold of activation.

In addition, extensive ex vivo HSC proliferation progressively results in a myeloid-biased differentiation, particularly megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis.41 Remarkably, Nilsson et al also found that, with age, the frequency of common lymphoid progenitors decreased whereas the frequencies of megakaryocytes/erythrocyte progenitors increased.42 Notably, we, and others, also show that UM171 exposure promotes HSC’s lymphoid potential, while suppressing the differentiation of erythrocytes and megakaryocytes (as previously reported43-45 and shown in this study).

Our work also supports the link between MYC-induced cumulative proliferation and loss of regenerative capacity, because we clearly demonstrate that enforced expression of MYC affects UM171-expanded HSC repopulating capacity, particularly impairing their lymphoid potential.

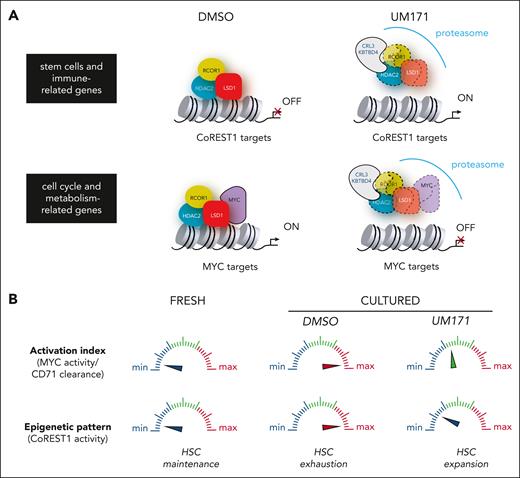

In summary, our work emphasizes the importance of 2 interconnected determinants (epigenetic and metabolic) for achieving expansion of functional HSCs. UM171-mediated CRL3KBTBD4 potentiation not only preserve HSCs epigenetic signature through CoREST1 degradation but also limits division rate, CD71 clearance, and protein synthesis, potentially through MYC reduction, thus ensuring their full regenerative potential (Figure 7).

Highlights of 2 critical determinants (epigenetic and metabolic) for achieving optimal expansion of functional HSCs. (A) UM171-mediated CRL3KBTBD4 potentiation preserves HSCs epigenetic signature through CoREST1 degradation (upper panel) and restrain excessive HSC activation through reduction of MYC transcriptional activity (lower panel). (B) CoREST1 and MYC activity indexes may serve as a rheostat, controlling the balance between latent and primed HSCs thus preventing their functional decline upon ex vivo culture.

Highlights of 2 critical determinants (epigenetic and metabolic) for achieving optimal expansion of functional HSCs. (A) UM171-mediated CRL3KBTBD4 potentiation preserves HSCs epigenetic signature through CoREST1 degradation (upper panel) and restrain excessive HSC activation through reduction of MYC transcriptional activity (lower panel). (B) CoREST1 and MYC activity indexes may serve as a rheostat, controlling the balance between latent and primed HSCs thus preventing their functional decline upon ex vivo culture.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Frechette and V. Blouin-Chagnon for assistance with in vivo experiments; I. Boivin, A. Durant, and D. Gracias for CD34+ for CB-cell purification; G. A. Gosselin and A. Bellemare-Pelletier at the Institute of Research in Immunology and Cancer for technical support with flow cytometry sorting; and Charles Le Moyne Hospital for providing human umbilical CB units. The authors also thank Tara Macrae and Elisa Tomellini for critical reviewing and suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant PJT-178113), a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation grant (FDN143286), and the Stem Cell Network of Canada (ACCT2-10). M.F.T. was supported by Mitacs through the Mitacs Elevate Program.

Authorship

Contribution: J.C. designed and performed experiments, generated all the figures, and cowrote the manuscript; S.G. performed all proteomic experiments including co-immunoprecipitation and western blot analyses; L.M assisted with experiments aimed at characterizing CD71lo and CD71hi populations; N.M assisted with in vivo experiments; M.F.T. assisted with some experiments; and G.S. provided project coordination and cowrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.S. is founder and chief executive officer of ExCellThera, a small biotechnology company that owns an exclusive license to UM171. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Guy Sauvageau, Institut de Recherche en Immunologie et Cancérologie, C.P. 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville, Montréal, QC H3C 3J7, Canada; email: guy.sauvageau@umontreal.ca.

References

Author notes

Raw, bulk transcriptome, single-cell RNA sequencing, and whole genome CRISPR screen data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus under the following accession codes: GSE157294, GSE157295, GSE157296, and GSE232227.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal