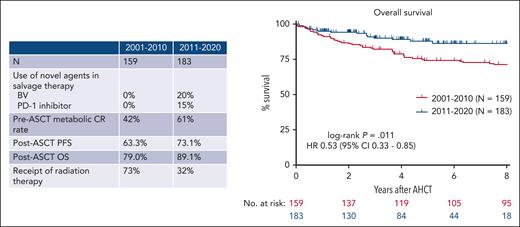

In this issue of Blood, Spinner et al compare outcomes in patients with relapsed classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) who underwent autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in the modern era (2011-2020) with those treated from 2000 to 2010 and find a significant improvement in 4-year overall survival (OS) among patients in the modern era (89.1% vs 79.0%) (see figure).1 These improved outcomes appear to be driven by an increased use of the novel agents, brentuximab vedotin and PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab), both as part of salvage therapy before ASCT and for relapse after ASCT. In a multivariable analysis, receipt of a PD-1 inhibitor before ASCT was associated with improved OS. In addition, the 4-year OS of patients who developed recurrent disease after ASCT improved from 43.3% to 71.4% in the modern era.

OS among patients with R/R cHL has improved in the modern era compared with 2001 to 2010.

OS among patients with R/R cHL has improved in the modern era compared with 2001 to 2010.

This analysis builds on the findings of other studies that suggest that novel agents (BV and PD-1 inhibitors) have profoundly changed the outcomes for patients with relapsed cHL. Multiple phase 2 studies incorporating novel agents into salvage regimens have reported higher complete response rates than historical outcomes with standard chemotherapy regimens.2,3 Treatment with PD-1 inhibitors before ASCT may be particularly beneficial as there is growing evidence that PD-1 blockade may increase sensitivity to subsequent high dose chemotherapy. A multicenter retrospective study analyzed the outcomes of 78 patients with multiply relapsed or refractory (R/R) cHL who underwent ASCT after PD-1 inhibitor containing salvage therapy. Despite receiving a median of a 4 lines of therapy before ASCT, patients achieved an 18-month progression-free survival (PFS) of 81%.4 Phase 2 clinical trials of pembrolizumab plus gemcitabine, vinorelbine and doxil (PGVD)5 as well as brentuximab plus nivolumab (BV-nivo)6 reported very high complete response rates. In the PGVD study, no patient had relapsed after a median follow-up of 13.5 months, whereas in the BV-nivo trial the 3-year PFS of patients who proceeded directly to ASCT after study therapy was 91% (3-year PFS 77% for the entire trial population). In this study, only 15% of patients treated in the modern era received PD-1 inhibitors before ASCT, and the outcomes for patients in this period would likely be even more favorable with the uniform receipt of pre-ASCT PD-1 inhibitors. A prospective, randomized trial comparing treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor + chemotherapy with chemotherapy alone is planned by the US cooperative groups and could provide definitive evidence supporting the use of PD-1 inhibitors in the second line setting.

The results of this study raise other important questions about peri-ASCT management. Similar to prior studies, the authors identified that achieving a complete response (CR) before ASCT was associated with improved outcomes. Among patients treated in the modern era on this study, only 61% of patients were in metabolic CR at the time of ASCT. Moskowitz et al previously demonstrated that patients in CR had similar outcomes regardless of whether they required 1 or more lines of salvage chemotherapy.7 With the availability of multiple highly active novel agent-based salvage regimens, should all patients in a partial response receive additional therapy with the goal of achieving a CR before high dose chemotherapy? Radiation therapy can be used before or after ASCT with the goal of reducing the risk of relapse, but its use is associated with long-term morbidity. Spinner et al report improvements in PFS after ASCT despite a significant reduction in the use of peri-ASCT radiation therapy in the modern era (32% vs 73%). Is peri-ASCT radiation needed, given the improved outcomes with novel agent-based salvage regimens? Finally (and most provocatively), with the activity of novel agents for R/R cHL, is ASCT required in all patients? For those who achieve CR after checkpoint inhibitor combined with chemotherapy, the contribution of high dose chemotherapy (with its associated risks) is not clear. A phase 2 study testing 6 to 8 cycles of tislelizumab (a novel PD-1 inhibitor), gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin followed by tislelizumab maintenance (without ASCT) in patients with R/R cHL reported a 1-year PFS of 96%.8 A similar trial using PGVD followed by pembrolizumab maintenance is also underway. Longer follow-up is needed to understand the durability of responses with these approaches. For select patients with excellent responses to PD-1 containing salvage regimens, it is possible that cure may be achieved without ASCT. Similarly, for patients with localized disease at relapse, involved site radiotherapy combined with novel agents might provide durable disease control without the risk associated with high dose chemotherapy.

Many published and ongoing clinical trials are assessing the impact of the up-front use of regimens incorporating brentuximab and PD-1 inhibitors. Although the number of patients with primary refractory and relapsed disease will almost certainly decline over time as a result, further study is necessary to evaluate the long-term outcomes, including the OS and late effects compared with treatment with standard chemotherapy regimens. Because novel agents are being increasingly used in the frontline setting, strategies for salvage regimens may also need to change. Whether patients previously exposed to PD-1 inhibitors will remain sensitive to immunotherapy at relapse is an open question. Finally, many, if not most, patients relapsing after ASCT today will have already received both BV and PD-1 inhibitors. Treatment options for these patients are limited and novel treatment approaches are needed. Unlike non-Hodgkin lymphoma for which CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have proven to be an invaluable treatment option, autologous CAR therapies in Hodgkin lymphoma have so far failed to reliably achieve durable remissions. For patients relapsing after ASCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation remains an important consideration and its use did not change across the 2 periods in this study.

As novel agents are used more frequently and in earlier phases in therapy, outcomes for patients with cHL have undeniably improved, but more work is needed to determine the optimal place for BV and PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of cHL.

Conflicts-of-interest disclosure: R.W.M. provides consulting for Genmab, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), AbbVie, Intellia, and Epizyme and received research funding from BMS, Merck, Genentech/Roche, and Genmab. A.S.L. provides consulting for Research to Practice and is on the advisory boards of Kite and Seagen.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal