In this issue of Blood, Burgos da Silva et al describe features of the intestinal microbiome that predict organ specific graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and, thereby, clinical outcomes, in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT).1

Most of us, at least in the medical profession, have become accustomed to the idea that our gut bacteria determine our well-being. Some of us will have had the personal experience that intake of antibiotics can generate a certain uneasiness of the belly, and perhaps much worse. One of the procedures where the microbiome is a major driver of the outcome is allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT). Allo-HCT is a potentially curative therapy for hematologic malignancies and a number of other conditions, but the occurrence of GVHD is a profound limiting factor.2 There is already ample evidence that links the intestinal microbiome, especially perturbations of the bacterial community, to GVHD.3 The nature of these links, the ability of the microbiome composition to predict GVHD in a given patient, and whether different organ involvement in GVHD is governed by different microbe-dependent mechanisms are all intensively researched areas.

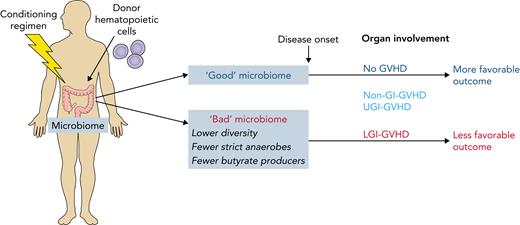

The current study explores microbiome changes that may have organ-specific effects in GVHD. Although GVHD is triggered by the simple entry of bacteria into intestinal tissues because of conditioning,4 the regulatory functions of the microbiome go way beyond inducing inflammation. The perturbations of the microbiome observed in GVHD may involve the overgrowth of “inflammatory” bacteria such as Enterococcus5 and the loss of the “good” species, especially strict anaerobes,6 altering the inflammatory potential and changing the profile of bacterial metabolites that may affect the host. Burgos da Silva et al find that the composition and metabolism of the microbiome before GVHD onset affect organ involvement in GVHD and are predictive of GVHD-related patient outcome. This work expands earlier ideas that several different pathogenetic processes contribute to organ-specific GVHD.

GVHD can involve different organs. Some organ-specific disease, such as skin-only GVHD, responds well to treatment while the disease in other organs, especially the lower gastrointestinal tract (LGI), is associated with lower treatment response rates and higher mortality.7 The current study found more severe dysbiosis, with a number of specific alterations to the microbiome, as well as major changes in the metabolic activity of the bacteria, in LGI-GVHD (see figure). It is currently difficult to be certain whether this is a qualitative difference or simply a more severe disturbance. However, the results show that the microbiome composition and loss of specific groups of bacteria before the onset of GVHD are associated with disease severity and clinical outcome.

Conditioning for allo-HCT causes microbiome-dependent inflammation and can lead to the attack of various organs by donor-derived immune cells (GVHD). Burgos da Silva et al report a number of features of the intestinal microbiome that determine whether GVHD will occur, which organs are affected (the most severe form is GVHD of the lower gastrointestinal tract, LGI-GVHD), and that affect disease outcome. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Conditioning for allo-HCT causes microbiome-dependent inflammation and can lead to the attack of various organs by donor-derived immune cells (GVHD). Burgos da Silva et al report a number of features of the intestinal microbiome that determine whether GVHD will occur, which organs are affected (the most severe form is GVHD of the lower gastrointestinal tract, LGI-GVHD), and that affect disease outcome. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

The healthy intestine hosts roughly 500 to 1000 species of bacteria, with only a small minority that can cause infections. GI bacteria may look similar, but these bacterial species are actually incredibly different from each other, with very different growth requirements and producing very different metabolites. With this great diversity and the great variation in species among human individuals, it is surprising that individual groups of bacteria, in some cases down to the genus level, are clearly associated with LGI-GVHD. The LGI has the highest bacterial density, but whether this high density is in fact relevant for LGI-GVHD is unclear. Human studies of the intestinal microbiome are limited to fecal samples; we can, therefore, not be sure about composition and activity of the microbiome along the GI tract, and whether this changes during treatment.

Bacteria metabolize intestinal nutrients and generate a great number of small molecules with largely unknown impact on the host. Short-chain fatty acids, especially butyrate, are the best investigated metabolites, and butyrate can have beneficial effects both on epithelial cells and intestinal immune cells. In the current study, the ability of the microbiome to produce butyrate correlated with better patient outcome, with different bacterial metabolic pathways linked to disease. Although we are not yet able to predict the individual risk for a patient to develop GVHD from the microbiome in a meaningful way, it is at least conceivable that we will one day arrive at this point.

Patients undergoing allo-HCT are at great risk of severe bacterial infection, requiring treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study confirms earlier data that these antibiotics disturb the microbiome, and the authors show an association of antibiotic treatment and the risk of GVHD. The importance of antibiotics in medicine is undisputed but, in addition to the selection of resistant bacteria, microbiome toxicity has emerged as a severe side effect. In our current arsenal, there are no antibiotics that act reliably enough on pathogenic bacteria and spare the “good ones,” particularly the strict anaerobes in the gut. I cannot see this happening any time soon, and it may not even be possible, but devising such a weapon would certainly be an important step in medicine.

This study contributes to the growing body of information how the microbiome maintains our health and the importance of preserving its beneficial capacity. It provides an additional rational basis for clinical trials to test if preserving or restoring a healthy microbiome alters GVHD risk and severity. Trials to find the best choice of antibiotics, tests of dietary interventions, immunomodulatory approaches, and endeavors to restore or modulate the microbiome, through fecal microbiota transplantation, are all under way.3 As we advance in our understanding of what exactly the contribution is of the bacteria, and the fungi,8 in our intestine that sustains our health, we are also making progress in identifying potential ways to prevent or redress microbiome disturbance. Burgos da Silva et al contribute to the ability to predict and to stratify GVHD. The accumulating evidence suggests we will soon be in a better position to prevent and to treat the disease.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal