Abstract

High-dose melphalan supported by autologous transplantation has been the standard of care for eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) for >25 years. Several randomized clinical trials have recently reaffirmed the strong position of transplantation in the era of proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs combinations, demonstrating a significant reduction of progression or death in comparison with strategies without transplantation. Immunotherapy is currently changing the paradigm of MM management, and daratumumab is the first-in-class human monoclonal antibody targeting CD38 approved in the setting of newly diagnosed MM. Quadruplets have become the new standard in transplantation programs, but outcomes remain heterogeneous, with various response depth and duration. The development of sensitive and specific tools for disease prognostication allows the consideration of strategies adaptive to dynamic risk. This review discusses the different options available for the treatment of transplantation-eligible patients with MM in frontline setting.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 1% to 1.8% of all cancers and 10% to 15% of all hematologic malignancies. Although MM remains an incurable disease for most patients, overall survival (OS) has significantly improved over the past decades with the emergence of new classes of drugs, including immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors (PIs), and monoclonal antibodies. A long-term analysis of an international cohort of 7291 transplantation-eligible patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) showed a statistical cure fraction rate of 14.3%.1 For transplantation-eligible patients with NDMM, the standard of care includes an induction regimen before a high-dose (HD) melphalan course with autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT)2; consolidation therapy after ASCT is also often administered before a lenalidomide maintenance.

Transplantation remains the cornerstone

HD melphalan and ASCT should be still considered standard of care in 2021. The results of 3 randomized clinical trials were updated during the American Society of Hematology meeting in December 2020. The phase 3 EMN02/HOVON-95 trial included 1503 patients who received an induction of 3 to 4 cycles of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone followed by the first random assignment between bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone vs ASCT (single or double). A second random assignment compared 2 cycles of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRD) with consolidation vs without consolidation, and all patients received lenalidomide maintenance until progression or toxicity. With an extended median follow-up (FU) of 75 months, not only median progression-free survival (PFS) improved with ASCT compared with bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone (56.7 vs 41.9 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.73; P = .0001), but PFS2, time to next treatment, and OS (7-year OS, 69% vs 63%; HR, 0.8; P = .0342) were as well.3 In the phase 3 Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) Dana-Farber Cancer Institute 2009 trial, 700 patients were randomly assigned between 3 cycles of VRD as induction, followed by an HD melphalan course with ASCT and 2 VRD cycles as consolidation or a strategy without ASCT of 8 cycles VRD alone. Patients in both arms received lenalidomide maintenance for 1 year. The second interim analysis after a median FU of 44 months showed a significant PFS benefit for the transplantation arm (median PFS, 50 vs 36 months; HR, 0.70; P < .001). An extended FU at 89.8 months did not reveal any differences in PFS2 or OS. Interestingly, 62.2% and 60.2% of patients in the transplantation arm and VRD alone arm, respectively, were still alive at 8 years of FU as a result of the efficacy of salvage treatments; 76.7% of patients treated up front with VRD alone who started a second line underwent ASCT at relapse.4 The phase 3 FORTE trial randomly assigned 474 patients to 1 of 3 arms: induction with 4 cycles of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRD) followed by ASCT and then consolidation with 4 cycles of KRD; continuous treatment with 12 cycles of KRD; or induction with 4 cycles of carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (KCD) followed by ASCT and consolidation with 4 cycles of KCD. Previous results highlighted the similar response rates and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity rates between the KRD/ASCT/KRD and KRD12 arms, suggesting that ASCT would not benefit patients who received a carfilzomib-based regimen. However, after a median FU of 45 months, the sustained MRD negativity rate was superior in the KRD/ASCT/KRD arm in comparison with the KRD12 and KCD arms (68%, 54%, and 45%, respectively; P < .03), translating into a PFS benefit (median PFS, not reached vs 57; [HR, 0.64; P = .023] and 53 months, respectively).5 Of note, no study has randomly assigned patients to ASCT and a quadruple regimen containing an anti-CD38 antibody; the role of ASCT should be reassessed in this new quadruplet era. Furthermore, the standard conditioning regimen remains melphalan at a dose of 200 mg/m2; attempts to add bortezomib or busulfan have not improved the efficacy/toxicity balance.

Improvement of induction regimens

Regimens for induction therapy commonly include a PI, an IMiD, and dexamethasone. Bortezomib combined with dexamethasone or with doxorubicin and dexamethasone has demonstrated superiority over the historical combination of vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.6,7 The triplet bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) was shown to be superior to the 2 doublets bortezomib plus dexamethasone and thalidomide plus dexamethasone.8,9 PIs and immunomodulatory drugs have synergistic effects, and the importance of the combination has been demonstrated with bortezomib and then carfilzomib; VTD induction has resulted in better response rates compared with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone,10 and KRD is superior to KCD, with a rate of very good partial response (VGPR) or better at 74% compared with 61% after 4 cycles (P = .01) in the FORTE trial.11 In single-arm studies, the VRD regimen has been associated with high rates of VGPR and MRD negativity, as well as prolonged PFS.12-14 Instead of a direct comparison between VTD and VRD, an integrated analysis supports the benefit of VRD over VTD, with higher rates of VGPR or better and MRD negativity when 6 cycles of each are given followed by transplantation.15 Of note, induction has lengthened, both in terms of number of cycles and exposure to lenalidomide by cycle; 6 cycles (28 days each) of VRD are associated with higher response rates.13 The VRD triplet was considered standard induction treatment until the results of the CASSIOPEIA trial, which randomly assigned 1085 patients age <66 years between VTD and daratumumab plus VTD (D-VTD), were reported.16 The addition of daratumumab to VTD during induction and consolidation before and after transplantation induced significantly higher VGPR and complete response (CR) rates but also higher MRD negativity rates (34.6% in the D-VTD arm vs 23.1% in the VTD arm; odds ratio, 1.76; P = .0001). The high response rates translated into a significant improvement in PFS in the daratumumab arm. Based on these results, D-VTD was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency. The current debate over how to choose between D-VTD and VRD, or even D-VRD, as well as the debate over the use of KRD instead of VRD, will be addressed in the context of case 2.

Consolidation or not, but with maintenance

Because consolidation therapy post-ASCT is still being debated, it is not strongly recommended in recent practice guidelines.2 The definition of consolidation should be refined; is it only the classical addition of 2 to 4 cycles, or should a second ASCT in tandem be considered as consolidation? The second random assignment in the phase 3 EMN02/HOVON-95 trial compared post-ASCT consolidation with VRD vs no consolidation, although both cohorts subsequently received prolonged lenalidomide maintenance; a PFS benefit was demonstrated (median PFS, 58.9 vs 45.5 months; P = .014), with comparable OS at 5 years.17 These results challenged those from the BMT CTN 0702 STAMINA phase 3 trial comparing 3 strategies after transplantation: no consolidation and lenalidomide maintenance only, consolidation with 4 cycles of VRD followed by lenalidomide maintenance, and consolidation with a second ASCT followed by lenalidomide maintenance. In an intent-to-treat analysis, 3-year PFS, OS, and conversion rates to CR were similar across the 3 groups of 758 patients. However, with an extended FU, and focusing on the per-protocol high-risk patients who received consolidation, 5-year PFS increased to 43.7% for those receiving tandem ASCT vs 37.3% for those receiving ASCT/VRD (4 cycles) and 32% for those receiving only 1 ASCT before maintenance (P = .03 for comparison between tandem ASCT and no consolidation).18 The European Myeloma Network also demonstrated the benefit of double ASCT; in the intent-to-treat population, double ASCT improved both 5-year PFS and 5-year OS (53.5% and 80.3%) compared with single ASCT (44.9% and 72.6%; HR, 0.62; P = .036 and HR, 0.62; P = .022, respectively), especially in cytogenetic high-risk diseases.17 Based on these data, tandem ASCT is recommended for patients with genetically high-risk disease.

Maintenance treatment with lenalidomide has been extensively investigated among patients with transplantation-eligible NDMM.19-21 A meta-analysis of 1208 transplantation-eligible patients enrolled in 3 randomized phase 3 trials comparing lenalidomide maintenance and observation/placebo showed a 25% reduction in the risk of death in favor of lenalidomide maintenance therapy.22 Based on these 2 years of PFS benefit (52.8 vs 23.5 months) and 2.5 years of OS benefit over placebo, lenalidomide became the standard therapy in maintenance after ASCT. The benefit of lenalidomide in maintenance was confirmed by the Myeloma Research Council Myeloma-XI trial, demonstrating a median PFS of 50 months compared with 28 months for the observation group (HR, 0.47; P < .001).23,24 The duration of maintenance is an unresolved question; if comparison of data from the IFM 2009 and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute trials (maintenance for 1 year or until progression) provides some answers, the relevant issue is probably to find the middle ground between risk of relapse and long-term quality of life. Novel options, including the addition of daratumumab or a second-generation PI, will also be discussed in the context of case 2.

What is the best time to start treatment for a patient with NDMM?

MM results more from an accumulation of plasma cells than from highly aggressive proliferation, and in virtually all patients with MM, the disease evolves from an asymptomatic premalignant stage (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or smoldering MM [SMM]). The International Myeloma Working Group revised in 2014 the disease definition of MM to facilitate earlier diagnosis, before end-organ damage occurs (hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, or bone lesions; CRAB criteria),25 based on the identification of specific biomarkers distinguishing patients with SMM who have >80% probability of progression within 2 years. Beyond the CRAB criteria, presence of clonal bone marrow plasma cells ≥60%, and/or serum free light chain (FLC) ratio ≥100 (provided involved FLC level is >100 mg/L) and/or >1 focal lesion (provided it is >5 mm) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should lead to start of treatment (SixtyLightchainMRI [SLiM] criteria).

Nevertheless, these SLiM CRAB patients were included only in the most recent clinical trials dedicated to NDMM, and little is known about their prognosis. The question of slightly delaying the initiation of treatment for an asymptomatic patient (eg, well-tolerated anemia only or FLC ratio >100 only) is of particular interest in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The CASSIOPEIA trial was the first to describe a SLiM CRAB subpopulation; of 1085 randomly assigned patients, 81 had baseline parameters corresponding to the definition of a SLiM only subgroup (7.5%). Response rates, MRD negativity rates, and PFS did not differ significantly between SLiM only and CRAB subgroups.26 Except with patients who are diagnosed on an emergency basis, we often have several days or weeks to organize the start of therapy, including initiating vaccines, completing imaging, or performing dental and/or cardiovascular assessments, for example. Nowadays, there is no argument to further delay the start of therapy; in addition to the goal of avoiding organ damage in starting treatment, SLiM CRAB only patients do not seem to have better long-term prognosis than patients with CRAB organ damage.

Case-based discussions

Case 1

A 49-year-old woman was referred with osteolytic bone lesions of the pelvis and L5 vertebra and severe hypogammaglobulinemia. FLC-κ MM was diagnosed in May 2011, based on the presence of 12% of plasma cells in the bone marrow, FLC-κ measurement of 370 mg/L, and κ/λ FLC ratio of 60. The International Staging System (ISS)27 was 1, and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis did not reveal any adverse cytogenetic factors [ie, no t(4,14) translocation, no 17p deletion]. She was included in the IFM 2009 trial and randomly assigned to arm A (VRD alone). She received 8 21-day cycles of VRD followed by 13 cycles of lenalidomide at 10 mg per day, completed in December 2012. The best response was complete response, and postmaintenance MRD was undetectable at a sensitivity at 10−6 (using next-generation sequencing). Eight years later (in early 2021), there was no evidence of disease progression. FLC-κs were measured at 39.86 mg/L, with a slightly increased κ/λ FLC ratio of 4.72 (compared with 25.74 mg/L and ratio of 3.01 1 year earlier). Lumbar MRI showed no lytic or focal lesions, only L4-L5 and L5-S1 discopathy.

Rationale for delaying ASCT in first relapse

The absence of clear evidence of an OS benefit in favor of ASCT in the era of triplet therapy (especially VRD) and the potential long-term toxicities of ASCT could support arguments to postpone ASCT in first relapse. The potential long-term toxicities include secondary primary malignancies (SPMs) and, above all, the rare but life-threatening secondary leukemia. Nevertheless, the updated results of the IFM 2009 study did not show any significant differences in the incidence of SPMs after 8 years of FU between the 2 arms (VRD plus ASCT and VRD alone); incidence of SPMs was reported at 7.7% and 9.7% and at 0.9% and 1.7%, respectively, for myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia.4 This seems to be a lower relative risk in comparison with data reported by the Center of International Blood and Morrow Transplant Research.28

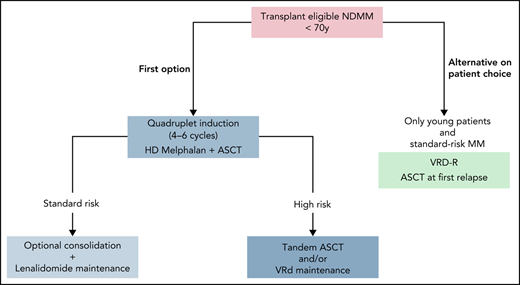

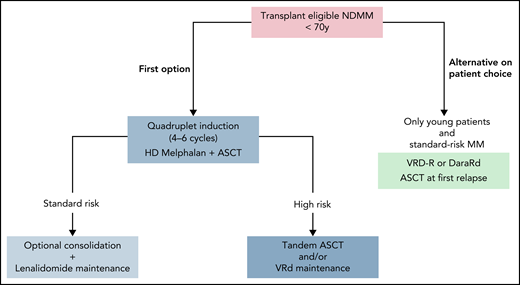

Ten years after diagnosis, this patient has a very good myeloma prognosis. This could have been anticipated from the beginning based on the favorable ISS score and the absence of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, but only the long-term outcome can confirm it. Such a long-responding patient who develops the disease at age <55 years could be the ideal patient in which to consider delayed ASCT at first relapse (Figure 1). Indeed, she would remain eligible for an intensive course of HD melphalan at relapse, which would not necessarily be the case for a patient developing the disease at age 65 years. On the other hand, we can assume that this patient had a very low MRD rate (close to true negativity) and that MRD could have been definitively eradicated by up-front ASCT.

How I treat transplantation-eligible NDMM outside clinical trials. Standard or high risk can be defined at diagnosis by cytogenetic analysis and/or during treatment according to depth of response (MRD evaluation).

How I treat transplantation-eligible NDMM outside clinical trials. Standard or high risk can be defined at diagnosis by cytogenetic analysis and/or during treatment according to depth of response (MRD evaluation).

For this patient, outside a clinical trial, I would have first proposed a transplantation-based strategy. Nevertheless, because of age and initial favorable risk, I would have been open to discussion with the patient about delayed ASCT, according to her situation and choice (eg, career obligations, desire to preserve an immediate good quality of life, and willingness to receive exclusively outpatient care).

Case 2

A 58-year-old man was diagnosed with immunoglobulin Gκ MM in 2012, with an immunoglobulin Gκ monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance having been known for 8 years. For 5 more years, the patient received only a watch-and-wait strategy for the SMM; M-spike was measured at 20 g/L in 2012, 25 g/L in 2014, and 29 g/L in 2016. Because of the increase in monoclonal component and a κ/λ FLC ratio >100, a bone marrow aspirate was repeated in 2017 and confirmed the presence of 17% plasma cells. M-spike was measured at 34.2 g/L, and the FLC-κs were dosed at 466.44 mg/L, with an FLC ratio of 124. The ISS score was intermediate (2). fluorescence in situ hybridization at diagnosis showed no t(4,14) or del(17p). Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) did not show any osteolytic lesions but did indicate several hypermetabolic focal lesions. The patient was offered inclusion in the CASSIOPEIA trial and was randomly assigned to the experimental arm. Induction consisted of 4 cycles of D-VTD, without any adverse events except a grade 1 sensory peripheral neuropathy. Postinduction assessment concluded the patient had achieved CR (not stringent CR because of a slightly increased κ/λ ratio) with undetectable MRD at 10−5 using 8-color flow. Induction was followed by HD melphalan and ASCT and then consolidation with 2 cycles of D-VTD. The patient no received maintenance therapy. At the last assessment 2 years after the end of consolidation, the patient was in sustained CR with sustained MRD negativity by flow of 10−5.

Which induction before HD melphalan and transplantation?

VRD and D-VTD are the 2 preferred options for induction in transplantation-eligible NDMM.2 Lenalidomide is an easy-to-use and well-tolerated drug, and some physicians could be reluctant to go back to thalidomide. However, data from the CASSIOPEIA study are reassuring in terms of toxicity and very promising in terms of response and survival.16 Adding daratumumab to VTD is feasible; >90% of patients underwent ASCT in both arms. Because CD34+ committed stem cells express a low level of CD38, some concerns about the stem cell yield were expected. The mean number of CD34+ stem cells collected was lower for patients receiving D-VTD vs VTD (6.7 vs 10 × 106/kg; P < .0001), and plerixafor was administrated to more patients in the D-VTD arm in comparison with the VTD arm (21.7% vs 7.9%; P < .0001). Among 1085 patients enrolled in the trial, mobilization failure was noted only in 3 patients (2 in the D-VTD arm and 1 in the VTD arm), and among those who received apheresis, a similar percentage of D-VTD– and VTD-treated patients underwent ASCT (97.0% vs 98.8%; P = .0758), with no differences in hematopoietic reconstitution.29 The second concern is the incidence of peripheral neuropathy induced by the combination of thalidomide and bortezomib; grade 3 or 4 peripheral neuropathy was reported in 9% of patients treated with (D)-VTD in the CASSIOPEIA trial, compared with 3.9% in the PETHEMA/GEM12 study treated with VRD13 and 7.1% in the GRIFFIN study treated with D-VRD.30 This excess of neurologic toxicity is quite manageable, without any significant impact on quality of life in the CASSIOPEIA trial.31 Only indirect comparisons can provide an answer to the question, “VRD or D-VTD?” An unanchored matching-adjusted indirect comparison of PFS and OS with D-VTD vs VRD was recently performed; after matching adjustment, significant improvements in PFS and OS were estimated for D-VTD vs VRD (HR, 0.47 and 0.31, respectively).32 These data support the use of quadruplet regimens in induction in transplantation-eligible NDMM. To date, only D-VTD is approved, but there is evidence that the replacement of thalidomide by lenalidomide30 and the use of carfilzomib-based quadruplet combinations may be preferred in the future because of the high depth of response they have induced33 (Table 1), with a well-tolerated profile. Of note, KRD was not shown to be superior to VRD in the phase 3 randomized ENDURANCE trial,34 but the study was not conducted in transplantation-eligible patients only.

Postconsolidation or premaintenance depth of response across studies

| . | Study . | ≥VGPR, % . | MRD negativity (10−5), % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| VRD ×8 | IFM 20094 | 69 | ∼28 (21 at 10−6) |

| VRD ×3/ASCT/VRD ×2 | IFM 20094 | 79 | ∼40 (30 at 10−6) |

| VRD ×6/ASCT/VRD ×2 | GEM12MENOS6513,14 | 75 | 57 |

| VTD ×4/ASCT/VTD ×2 | CASSIOPEIA16 | 78 | 44 |

| D-VTD ×4/ASCT/D-VTD ×2 | CASSIOPEIA16 | 84 | 64 |

| VRD ×4/ASCT/VRD ×2 | GRIFFIN30 | 73 | 17 |

| D-VRD ×4/ASCT/D-VRD ×2 | GRIFFIN30 | 91 | 47 |

| KRD ×12 | FORTE5 | 87 | 54 |

| KRD ×4/ASCT/KRD ×4 | FORTE5 | 89 | 58 |

| D-KRD ×8 | MANHATTAN33 | 95 | 77 |

| . | Study . | ≥VGPR, % . | MRD negativity (10−5), % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| VRD ×8 | IFM 20094 | 69 | ∼28 (21 at 10−6) |

| VRD ×3/ASCT/VRD ×2 | IFM 20094 | 79 | ∼40 (30 at 10−6) |

| VRD ×6/ASCT/VRD ×2 | GEM12MENOS6513,14 | 75 | 57 |

| VTD ×4/ASCT/VTD ×2 | CASSIOPEIA16 | 78 | 44 |

| D-VTD ×4/ASCT/D-VTD ×2 | CASSIOPEIA16 | 84 | 64 |

| VRD ×4/ASCT/VRD ×2 | GRIFFIN30 | 73 | 17 |

| D-VRD ×4/ASCT/D-VRD ×2 | GRIFFIN30 | 91 | 47 |

| KRD ×12 | FORTE5 | 87 | 54 |

| KRD ×4/ASCT/KRD ×4 | FORTE5 | 89 | 58 |

| D-KRD ×8 | MANHATTAN33 | 95 | 77 |

Bold type indicates rates of VGPR >80% or MRD negativity >60%.

Table 1 shows the synergy between the most efficient combinations and ASCT; the true benefit is probably indicated by the proportion of patients who achieve MRD negativity and maintain it, with the hope that some of them will obtain operational cure.

Which maintenance after HD melphalan and transplantation?

A large meta-analysis demonstrated that lenalidomide maintenance offers PFS and OS benefits of >2 and 2.5 years over placebo, but in this analysis, there was no benefit in patients with ISS 3 disease or high-risk cytogenetics.22 However, the Myeloma Research Council Myeloma-XI trial reported contrary data on 1971 patients (1137 patients assigned to lenalidomide maintenance and 834 patients to observation); in high-risk patients, 3-year OS was 75% in the lenalidomide group compared with 64% in the observation group (HR, 0.45), and in ultrahigh-risk patients, it was 63% vs 43.5%, respectively (HR, 0.42).23 Although lenalidomide maintenance also benefited high-risk patients, it did not abrogate the poor cytogenetic prognosis, and other data have suggested that high-risk patients could benefit from PI-based maintenance.35-37 The results of the second random assignment in the FORTE trial are promising; the use of carfilzomib plus lenalidomide as maintenance prolonged PFS in comparison with lenalidomide alone (30-month PFS, 81% vs 68%), including in the high-risk subgroup (HR, 0.59).5 Moreover, the second part of the CASSIOPEIA trial investigated an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody as monotherapy in the maintenance setting; more FU is needed to determine which patients will benefit the most. PIs and anti-CD38 antibodies will probably not replace lenalidomide in the maintenance setting, but they can be combined with it; the results of 2 randomized phase 3 trials assessing the combinations of lenalidomide plus ixazomib (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02406144; conducted by the PETHEMA group) and of lenalidomide plus daratumumab (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03901963; the AURIGA trial) are awaited. Nowadays, only lenalidomide is approved in the maintenance setting, and I recommend using it as monotherapy for patients with standard-risk myeloma for a fixed duration of 2 or 3 years, depending on the efficacy/tolerance balance. For high-risk myeloma (defined by cytogenetics at diagnosis and/or treatment response by MRD assessment), I would prefer to consider tandem ASCT and/or reinforced maintenance with VRD or including ixazomib, while waiting for better options (Figure 1).

For this patient, outside a clinical trial, my approach would be quadruplet D-VTD induction therapy for 4 cycles, followed by stem cell mobilization using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and plerixafor, then HD melphalan with ASCT, consolidation of 2 D-VTD cycles, and lenalidomide maintenance over 2 or 3 years (according to response and long-term tolerability). In the near future, because D-VRD will probably be approved based on the results of the PERSEUS trial (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03710603), I would replace thalidomide with lenalidomide.

Case 3

A 55-year-old woman was diagnosed with FLC-κ MM in March 2020 after a left iliac plasmocytoma was discovered. The bone marrow aspirate showed the presence of 49% clonal plasma cells. The FLC-κs were dosed at 2726 mg/L, and the κ/λ FLC ratio was 1040. The ISS score was favorable (1), and the lactate dehydrogenase level was normal. Multiparametric cytogenetic analysis at diagnosis was performed using next-generation sequencing and indicated a favorable linear predictor38 score of −0.3 [hyperdiploidy with 3, 9, and 11 trisomies, 13 monosomy, 6q and 1q partial deletion (non 1p32), Xp partial gain, t(14,20) but no t(4,14) and no t(14,16), and no del(17p); clonal BIRC3 mutation). Baseline PET-CT showed diffuse osteomedullary hypermetabolism of the axial skeleton. The patient received 4 28-day cycles of VRD followed by melphalan at 200 mg/m2 with ASCT in September 2020 and then 2 VRD cycles as consolidation. The best response after consolidation was CR; no bone marrow MRD assessment was performed. PET-CT after consolidation revealed no residual tumor burden by imaging. Lenalidomide maintenance was initiated in January 2021 in CR status at 10 mg per day for 21 of 28 days. Twelve weeks later, the patient was asymptomatic, but the FLC-κ dose was increased to 810 mg/L (κ/λ FLC ratio, 80). Progressive disease was confirmed 10 days later (FLC-κ dosed at 1506 mg/L, with κ/λ FLC ratio of 241). The cytogenetic analysis at relapse highlighted a clonal evolution with acquisition of 1q gain and subclonal BRAF mutation (no V600E).

Unexpected early relapses: how can they be avoided?

This patient, who seemed at the beginning to have an easy-to-treat MM, unfortunately experienced an early relapse, which is associated with poor prognosis regardless initial cytogenetic risk.39 Insufficient depth of response and clonal evolution can promote early relapse.

Role of MRD evaluation

Because persistent disease undetectable with standard methods leads to relapse, the International Myeloma Working Group defined new criteria for response and MRD assessment in 2016.40 Beyond its huge prognostic value, MRD highlights the notion of dynamic risk in MM; I am convinced that the time has come to use it to adapt strategies accordingly. Although it is not yet established in daily clinical practice, many ongoing clinical trials are using it, not only as a surrogate marker but also as a decisional factor for adapted therapy.

Remaining issues: clonal evolution and role of microenvironment

The frequency of clonal evolution is lower in NDMM than in relapsed or refractory MM, and the role of HD melphalan in this clonal evolution remains unclear.40 We are not yet able to predict clonal evolution at diagnosis, and to date, there is no specific strategy to avoid or limit clonal evolution in NDMM. In the future, it might be helpful if we are able to monitor the clonal heterogeneity of the disease using single-cell sequencing and describe the immune and stromal microenvironments. Perhaps we would be able to select personalized treatment strategies through the analysis of clonal and immune variations.

For this patient in 2020, before the reimbursement of daratumumab, I would not have had any other proposal; it was not suitable to consider tandem transplantation and/or reinforced maintenance in the absence of adverse prognostic factors. Only MRD-based strategies could be tailored to this situation, and I would encourage inclusion in dedicated clinical trials. In 2021 for such a patient, the use of a quadruplet regimen including an anti-CD38 antibody would also probably minimize the risk of early clonal evolution by combining synergistic mechanisms of action and contributing to the enhancement of the immune system.

Conclusion

Recent advances have secured the place of quadruplets in induction before an intensive course of melphalan supported by ASCT in transplantation-eligible NDMM. Promising data suggest the use of carfilzomib as a PI in such regimens to increase CR and MRD negativity rates. Several studies have recently reaffirmed the place of up-front ASCT in the triplet era. Sustained MRD negativity seems to be the most potent prognostic factor, surpassing at least partially cytogenetics at diagnosis. The time has come to use it to adapt strategies to dynamic risk. A new challenge will be to use the most effective quadruplets before and after transplantation to cure as many patients as possible, while maintaining an acceptable quality of life and a suitable balance of risk/cost benefit. The purpose of the current studies is to validate response-adapted strategies (deescalate therapy for good responders and escalate for poor responders). Soon, modern immunotherapies such as bispecific antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T cells will probably also be integrated into therapy sequences in transplantation-eligible NDMM.

Acknowledgment

The author particularly thanks the IFM group.

Authorship

Contribution: A.P. wrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.P. receives honoraria from and serves on advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi and Takeda.

Correspondence: Aurore Perrot, Service d’Hématologie du CHU de Toulouse, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, 1 avenue Irène Joliot Curie, 31059 Toulouse Cedex, France; e-mail: perrot.aurore@iuct-oncopole.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal