Abstract

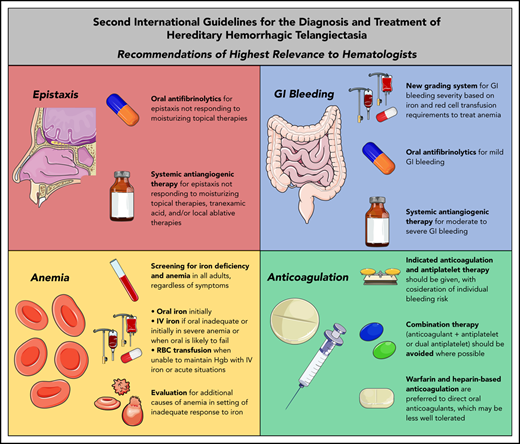

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) management is evolving because of the emergence and development of antiangiogenic therapies to eliminate bleeding telangiectasias and achieve hemostasis. This progress is reflected in recent clinical recommendations published in the Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of HHT, in which systemic therapies including antiangiogenics and antifibrinolytics are now recommended as standard treatment options for bleeding. This review highlights the new recommendations especially relevant to hematologists in managing bleeding, anticoagulation, and anemia in patients with HHT.

Introduction

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT; Osler-Weber-Rendu disease) is an autosomal dominant rare bleeding disorder occurring in 1 of 5000 persons worldwide. The disease was first described by the British pathologist Henry Gawen Sutton in 1864,1 but it would be another 32 years before it was distinguished from hemophilia by the French physician Henri Jules Louis Marie Rendu.2 In the 20th century, the primary management of these 2 hereditary bleeding disorders took distinctly different paths: systemic therapy in hemophilia to replace what was missing, and procedural therapy in HHT to eliminate what was abnormally present. However, the discovery and characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) at the end of the 20th century3,4 and subsequent elucidation of the underlying pathophysiology of HHT have resulted in the development of new treatment options: systemic, targeted therapies to address the VEGF excess5 in these patients. Based on mouse models of HHT, it is hypothesized that VEGF excess supports the growth of the telangiectasias that cause bleeding and that elimination of this excess can restore hemostasis.

It was on the backdrop of this ongoing evolution of HHT treatment that the Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (hereinafter referred to as the “Second International HHT Guidelines” or simply “the guidelines”) were developed. The Second International HHT Guidelines were developed using the AGREE-II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II) framework and GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology, using a systematic search strategy, literature review, and incorporation of expert evidence in a structured consensus process where published literature was lacking. Recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine,6 these guidelines focus on 6 priority topic areas, of which several are of high relevance to hematologists: anemia and anticoagulation, epistaxis, and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. In this focused review, each of these areas and the new recommendations are examined and contextualized by the ongoing systemic therapy evolution occurring in the management of HHT.

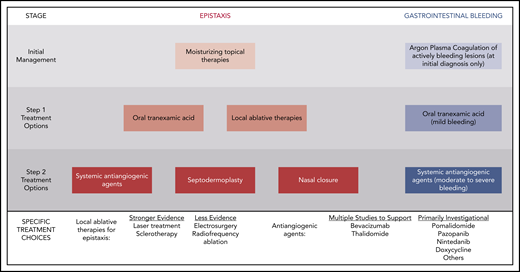

Systemic therapy for epistaxis

Recurrent and often severe epistaxis is the most common manifestation of HHT, occurring in >90% of adults.7 Epistaxis in HHT can last for hours per day and cause significant psychosocial morbidity, social isolation, and difficulties with employment, travel, and routine daily activities.7 Moisturization of the nasal mucosa through air humidification and topical application of saline solution or gels is a mainstay of epistaxis prevention to reduce cracking and bleeding of fragile telangiectasias, but that treatment alone is inadequate for many patients.8 Although epistaxis was a priority topic in the initial HHT guidelines published in 2009, treatment recommendations were focused on surgical intervention without recommendation of systemic therapies.9 This approach has changed significantly in the Second International HHT Guidelines, with several systemic therapies recommended on equal standing with local surgical treatments (Figure 1).

Stepwise approach to bleeding management in HHT advocated in the Second International HHT Guidelines.

Stepwise approach to bleeding management in HHT advocated in the Second International HHT Guidelines.

In 2014, the oral antifibrinolytic agent tranexamic acid demonstrated efficacy in reducing epistaxis in HHT in 2 randomized, controlled trials, with a 17.3% reduction in the duration of epistaxis per month in a trial of 118 patients and a reduction in a composite epistaxis end point (factoring both the duration and intensity of epistaxis) of 54% in another crossover trial of 22 patients.10,11 There was no improvement in hemoglobin (although the patients were not, on average, severely anemic at baseline) or increase in thrombotic complications. On the strength of this evidence, oral tranexamic acid is now recommended as an option for management of epistaxis that does not respond to moisturizing topical therapies alone (Table 1).

Clinical Recommendations from Second International HHT Guidelines of high relevance to hematologists

| Clinical recommendation . | Clinical considerations . |

|---|---|

| Epistaxis | |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider the use of oral tranexamic acid for the management of epistaxis that does not respond to moisturizing topical therapies (ER2; QOE: high, SOR: strong). | Can be coadministered with systemic antiangiogenic therapy. Dosing: start at 500 mg twice daily, gradually increasing up to 1000 mg 4 times daily or 1500 mg 3 times daily. Dose per pill varies by country, and these recommended doses can be approximated and adapted given what is available. Contraindications include recent thrombosis; relative contraindications include atrial fibrillation or known thrombophilia. |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider the use of systemic antiangiogenic agents for the management of epistaxis that has failed to respond to moisturizing topical therapies, ablative therapies and/or tranexamic acid (ER4; QOE: moderate, SOR: strong). | IV bevacizumab is given as induction (5 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 4-6 doses) followed by maintenance (dosing variable; 5 mg/kg every 1-3 months is an option). Risk of long-term maintenance therapy unknown. Monitor for hypertension, proteinuria, infection, delayed wound healing, VTE. Oral thalidomide can also be considered, though side effects often limit long term use. Risks and benefits of antiangiogenic medications should be considered, as well as alternatives, such as septodermoplasty and nasal closure, in these patients. Shared decision making with patients is crucial. |

| GI bleeding | |

The expert panel recommends that clinicians grade the severity of HHT-related GI bleeding and proposes the following framework:

| For most HHT patients (and in particular, those without comorbid conditions resulting in chronic anemia), the hemoglobin goal will be a normal hemoglobin for age and gender. This classification is not for the acutely anemic patient during the initial diagnostic phase, but rather for HHT patients who are post initial iron repletion (≥3 months after diagnosis) and is meant to represent chronic hematologic support requirements. Need for regular, scheduled IV iron (rather than an isolated single dose) defines patients in the moderate or severe category. This classification is considered proposed for future development. |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider treatment of mild HHT-related GI bleeding with oral antifibrinolytics (GR5; QOE: low, SOR: weak). | Can be coadministered with systemic antiangiogenic therapy. Dosing: start at 500 mg twice daily, gradually increasing up to 1000 mg 4 times daily or 1500 mg 3 times daily. Dose per pill varies by country, and these recommended doses can be approximated and adapted given what is available. Contraindications include recent thrombosis; relative contraindications include atrial fibrillation or known thrombophilia. |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider treatment of moderate to severe HHT-related GI bleeding with intravenous bevacizumab or other systemic antiangiogenic therapy (GR6; QOE: moderate, SOR: strong). | IV bevacizumab is given as induction (5 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 4-6 doses) followed by maintenance (dosing variable; 5 mg/kg every 1-3 months is an option). Risk of long-term maintenance therapy unknown. Monitor for hypertension, proteinuria, infection, delayed wound healing, VTE. Risks, and benefits of antiangiogenic medications should be considered. Shared decision making with patients is crucial. |

| Anemia and anticoagulation | |

The expert panel recommends that the following HHT patients be tested for iron deficiency and anemia:

| Testing includes complete blood count and ferritin; if anemic but ferritin not reduced, obtain serum iron, total iron binding capacity, and transferrin saturation, and consider hematology consultation. |

The expert panel recommends iron replacement for treatment of iron deficiency and anemia as follows:

| Assess adequacy of response (hemoglobin rise of ≥1.0 g/dL, normalization of ferritin and transferrin saturation) at 1 month. Oral iron: can start with 35-65 mg of elemental iron daily; if inadequate, can consider increased daily dose or twice daily dose; if not tolerated, can attempt alternate oral iron preparation. IV iron dose can be guided by total iron deficit (Ganzoni formula 79 ) or a total empiric dose of 1 gram can be provided, with interval reassessment. |

| Regularly-scheduled iron infusions may be needed, and should be expected unless chronic bleeding is halted though systemic therapies and/or procedural interventions. | |

The expert panel recommends RBC transfusions in the following settings:

| Hemoglobin targets and thresholds for RBC transfusion should be individualized in HHT, depending on patient symptoms, severity of ongoing HHT-related bleeding, response to other therapies and iron supplementation, the presence of comorbidities and the acuity of the care setting. |

| The expert panel recommends considering evaluation for additional causes of anemia in the setting of an inadequate response to iron replacement (AR4; QOE: low, SOR: strong). | Typically testing should include measurement of folate, vitamin B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone and work-up for hemolysis, with referral to hematology in unresolved cases. |

| The expert panel recommends that patients with HHT receive anticoagulation (prophylactic or therapeutic) or antiplatelet therapy when there is an indication, with consideration of their individualized bleeding risks; bleeding in HHT is not an absolute contraindication for these therapies (AR5; QOE: low, SOR: strong). | Heparin agents and vitamin K antagonists are preferred to direct oral anticoagulants, as the latter may be less-well tolerated.54 Patients with HHT with atrial fibrillation who do not tolerate anticoagulation or are too high-risk for anticoagulation can consider alternate approaches to decreasing cardioembolic risk, such as left atrial appendage closure.80 |

| The panel recommends avoiding the use of dual antiplatelet therapy and/or combination of antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation, where possible, in patients with HHT (AR6; QOE:low [expert consensus], SOR: weak). | If dual or combination therapies are required, duration of therapy should be minimized and patients should be monitored closely. |

| Clinical recommendation . | Clinical considerations . |

|---|---|

| Epistaxis | |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider the use of oral tranexamic acid for the management of epistaxis that does not respond to moisturizing topical therapies (ER2; QOE: high, SOR: strong). | Can be coadministered with systemic antiangiogenic therapy. Dosing: start at 500 mg twice daily, gradually increasing up to 1000 mg 4 times daily or 1500 mg 3 times daily. Dose per pill varies by country, and these recommended doses can be approximated and adapted given what is available. Contraindications include recent thrombosis; relative contraindications include atrial fibrillation or known thrombophilia. |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider the use of systemic antiangiogenic agents for the management of epistaxis that has failed to respond to moisturizing topical therapies, ablative therapies and/or tranexamic acid (ER4; QOE: moderate, SOR: strong). | IV bevacizumab is given as induction (5 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 4-6 doses) followed by maintenance (dosing variable; 5 mg/kg every 1-3 months is an option). Risk of long-term maintenance therapy unknown. Monitor for hypertension, proteinuria, infection, delayed wound healing, VTE. Oral thalidomide can also be considered, though side effects often limit long term use. Risks and benefits of antiangiogenic medications should be considered, as well as alternatives, such as septodermoplasty and nasal closure, in these patients. Shared decision making with patients is crucial. |

| GI bleeding | |

The expert panel recommends that clinicians grade the severity of HHT-related GI bleeding and proposes the following framework:

| For most HHT patients (and in particular, those without comorbid conditions resulting in chronic anemia), the hemoglobin goal will be a normal hemoglobin for age and gender. This classification is not for the acutely anemic patient during the initial diagnostic phase, but rather for HHT patients who are post initial iron repletion (≥3 months after diagnosis) and is meant to represent chronic hematologic support requirements. Need for regular, scheduled IV iron (rather than an isolated single dose) defines patients in the moderate or severe category. This classification is considered proposed for future development. |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider treatment of mild HHT-related GI bleeding with oral antifibrinolytics (GR5; QOE: low, SOR: weak). | Can be coadministered with systemic antiangiogenic therapy. Dosing: start at 500 mg twice daily, gradually increasing up to 1000 mg 4 times daily or 1500 mg 3 times daily. Dose per pill varies by country, and these recommended doses can be approximated and adapted given what is available. Contraindications include recent thrombosis; relative contraindications include atrial fibrillation or known thrombophilia. |

| The expert panel recommends that clinicians consider treatment of moderate to severe HHT-related GI bleeding with intravenous bevacizumab or other systemic antiangiogenic therapy (GR6; QOE: moderate, SOR: strong). | IV bevacizumab is given as induction (5 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 4-6 doses) followed by maintenance (dosing variable; 5 mg/kg every 1-3 months is an option). Risk of long-term maintenance therapy unknown. Monitor for hypertension, proteinuria, infection, delayed wound healing, VTE. Risks, and benefits of antiangiogenic medications should be considered. Shared decision making with patients is crucial. |

| Anemia and anticoagulation | |

The expert panel recommends that the following HHT patients be tested for iron deficiency and anemia:

| Testing includes complete blood count and ferritin; if anemic but ferritin not reduced, obtain serum iron, total iron binding capacity, and transferrin saturation, and consider hematology consultation. |

The expert panel recommends iron replacement for treatment of iron deficiency and anemia as follows:

| Assess adequacy of response (hemoglobin rise of ≥1.0 g/dL, normalization of ferritin and transferrin saturation) at 1 month. Oral iron: can start with 35-65 mg of elemental iron daily; if inadequate, can consider increased daily dose or twice daily dose; if not tolerated, can attempt alternate oral iron preparation. IV iron dose can be guided by total iron deficit (Ganzoni formula 79 ) or a total empiric dose of 1 gram can be provided, with interval reassessment. |

| Regularly-scheduled iron infusions may be needed, and should be expected unless chronic bleeding is halted though systemic therapies and/or procedural interventions. | |

The expert panel recommends RBC transfusions in the following settings:

| Hemoglobin targets and thresholds for RBC transfusion should be individualized in HHT, depending on patient symptoms, severity of ongoing HHT-related bleeding, response to other therapies and iron supplementation, the presence of comorbidities and the acuity of the care setting. |

| The expert panel recommends considering evaluation for additional causes of anemia in the setting of an inadequate response to iron replacement (AR4; QOE: low, SOR: strong). | Typically testing should include measurement of folate, vitamin B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone and work-up for hemolysis, with referral to hematology in unresolved cases. |

| The expert panel recommends that patients with HHT receive anticoagulation (prophylactic or therapeutic) or antiplatelet therapy when there is an indication, with consideration of their individualized bleeding risks; bleeding in HHT is not an absolute contraindication for these therapies (AR5; QOE: low, SOR: strong). | Heparin agents and vitamin K antagonists are preferred to direct oral anticoagulants, as the latter may be less-well tolerated.54 Patients with HHT with atrial fibrillation who do not tolerate anticoagulation or are too high-risk for anticoagulation can consider alternate approaches to decreasing cardioembolic risk, such as left atrial appendage closure.80 |

| The panel recommends avoiding the use of dual antiplatelet therapy and/or combination of antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation, where possible, in patients with HHT (AR6; QOE:low [expert consensus], SOR: weak). | If dual or combination therapies are required, duration of therapy should be minimized and patients should be monitored closely. |

For a complete list of all recommendations, see the full guidelines publication.6 Recommendation number, quality of evidence (QOE), and strength of recommendation (SOR) are given after the recommendations. Clinical considerations from the expert panel are summarized from the published guidelines supplement.

RBC, red blood cell.

Increased VEGF drives telangiectasia and arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in HHT mouse models,12 and its normalization suppresses formation of these anomalous vascular structures.13 This finding has spurred development of systemic antiangiogenic agents that directly or indirectly inhibit VEGF in order to treat epistaxis and GI bleeding in HHT. Agents with sufficient published evidence to be evaluated in depth by the Guidelines Working Group included bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech) and thalidomide (Thalomid; Celgene), although several agents in development were also mentioned (Figure 1). Thalidomide is an immunomodulatory imide drug primarily used in the management of multiple myeloma that has been shown to downregulate VEGF levels in patients with HHT and improve vascular wall integrity.14,15 Although effectiveness in improving epistaxis has been documented in several small studies (67 patients),14-19 adverse events, in particular persistent neuropathy, has limited enthusiasm for the long-term use of this agent.

The antiangiogenic agent with the largest body of evidence in HHT is bevacizumab. Small retrospective studies evaluated by the Guidelines Working Group describe substantial improvements in epistaxis: 85% of patients achieved control of epistaxis in a 13-patient study20 and the epistaxis severity score (ESS; a well-validated 10-point epistaxis bleeding scale in HHT21 ) declined by 56% in a 34-patient study.22 The effectiveness of systemic bevacizumab is in contrast to prior trials of topical nasal bevacizumab23,24 and intranasal bevacizumab injections,25 which did not show significant benefit. On the strength of several relatively small studies available at the time of the guidelines conference,20,22,26-31 systemic antiangiogenic therapy is now recommended as an option for managing epistaxis that has failed to respond to moisturizing topical therapies, oral tranexamic acid, and/or local procedural ablative therapies (Table 1; Figure 1). After the conference, the results of the international, multicenter, retrospective InHIBIT-Bleed study describing the use of systemic bevacizumab in 238 patients with moderate-to-severe HHT-associated bleeding were published, bolstering the available evidence supporting this recommendation.32 In most of the patients, 1 or more local ablative treatments, antifibrinolytic therapy, or both had failed. In 146 patients treated for epistaxis for ≥3 months with complete ESS data available, the mean ESS improved from 6.81 at baseline to 3.44 with treatment, a relative reduction of 50% and an absolute reduction equal to nearly 5 times the minimal important difference of the ESS.33 Substantial improvements in hemoglobin, iron infusion needs, and red cell transfusion needs were also observed (described in greater detail in “Systemic therapy for GI bleeding”). Bevacizumab was safe, with a venous thromboembolism (VTE) rate of 2% and no fatal adverse events.

Systemic therapy for GI bleeding

GI bleeding develops in ∼30% of patients with HHT and is caused by mucosal telangiectasias in the stomach, small bowel, and/or colon.34-39 Incidence increases with age. Significant GI bleeding may be clinically evident or occult, with anemia as the primary consequence. Although recurrent epistaxis alone can result in anemia, patients with severe iron infusion or red cell transfusion-dependent anemia typically have concurrent chronic GI bleeding.

In addition to a new grading system for HHT-related GI bleeding (Table 1), the guidelines recommend systemic therapies as the primary modality for managing GI bleeding (Figure 1). Procedural hemostatic treatments, including Argon Plasma Coagulation, are recommended only to treat an emergent, brisk bleed or acutely bleeding GI vascular lesions visualized at the time of diagnostic endoscopy, because there are insufficient data to support their systematic and repeated use to minimize the telangiectasia burden. Tranexamic acid is recommended for patients with mild GI bleeding on the basis of low potential for harm, but there is limited evidence of effectiveness.40 Systemic bevacizumab is recommended for patients with moderate or severe GI bleeding (those requiring intravenous iron or red cell transfusion) on the basis of substantial improvements in mean hemoglobin (3-4 g/dL increase), red cell transfusion (>80% reduction), and iron infusion (>70% reduction) described in single-center retrospective cohort studies.20,22,26 Most of the 238 patients treated with systemic bevacizumab in the aforementioned multicenter InHIBIT-Bleed study had GI bleeding. This study found a mean hemoglobin improvement of 3.2 g/dL, an 82% reduction in units of red cells transfused, and a 70% reduction in iron infusions, echoing the findings of the prior single-center studies.32

Anemia screening and management

Anemia is very common in patients with HHT, with a prevalence of ∼50%.41,42 The primary etiology of anemia, present in the great majority of cases, is iron deficiency from chronic bleeding. Concomitant shortened intravascular erythrocyte survival consistent with hemolysis may contribute in a subset of patients with anemia out of proportion to bleeding.43 Reflecting bleeding symptoms,38,42,44 anemia is more common with advanced age. Iron deficiency anemia in HHT results in typical signs and symptoms, including fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, pica, restless leg syndrome, hair loss, and others,45-48 and may considerably worsen symptoms of high-output cardiac failure in patients with significant liver AVMs.29,31

Anemia was not a priority topic area in the initial HHT guidelines9 and was included as such in the second guidelines in part because of the preguidelines survey input from patients, describing underrecognition and undertreatment of anemia that negatively impacted quality of life. As bleeding is chronic and progressive, the guidelines recommend screening for iron deficiency in all adults with HHT, irrespective of bleeding or anemia symptoms, and in children with recurrent bleeding and/or symptoms of anemia (Table 1). A screening interval is not specified but should be individualized given the heterogeneity of bleeding symptoms. Consideration for hematology consultation is additionally recommended in patients with anemia but without reduced ferritin, to ensure the accuracy of the diagnosis and evaluate for alternative or complicating etiologies of anemia. Oral iron is recommended as the initial therapeutic consideration, but the guidelines emphasize that intravenous iron be considered first line in patients presenting with severe anemia or those in whom oral replacement is expected to be inadequate or ineffective. Additional anemia recommendations regarding indications for hematology referral and red cell transfusion are described in Table 1.

Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in HHT

The inclusion of anticoagulation among the priority topics in the Second International HHT Guidelines acknowledges the significant uncertainty and misconceptions of patients and providers regarding these treatments. Although HHT is a bleeding disorder, it provides no protection against thrombotic complications. In fact, HHT may result in an elevated thrombotic risk, which has been associated with iron deficiency and elevated factor VIII levels.49-51 Therefore, the guidelines recommend treatment with anticoagulation (prophylactic or therapeutic) or antiplatelet therapy when indicated, with consideration of individualized bleeding risk (Table 1). Therapeutic anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents are tolerated by most patients with HHT52,53 and therefore should not be regularly withheld in such patients because of bleeding concerns. The specified exception is the use of combination therapy, either dual antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation plus antiplatelet therapy. Avoidance of such combination therapy, or at least minimization of duration, is recommended wherever possible. In patients poorly tolerating indicated anticoagulation, hemostatic treatments (systemic or local) or anticoagulation modification can be pursued. The guidelines further note that heparin agents and vitamin K antagonists are preferred rather than direct oral anticoagulants because the latter may be less well tolerated in HHT due to increased risk of bleeding.54 A prospective study is ongoing to further evaluate the safety of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in patients with HHT who have ongoing chronic bleeding.55 A recent interim analysis published after the guidelines conference included the first 12 patients treated with a mean follow-up of 6.5 months and found that therapy was well tolerated overall, with no major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events.

Key areas of uncertainty

There are several areas of uncertainty in the topics discussed herein.

Role of hormonal therapies

Limited data are available for the use of systemic estrogens, progestins, and selective estrogen response modifiers (tamoxifen, raloxifene, and bazedoxifene)56-59 to reduce epistaxis and GI bleeding in HHT, and beneficial effects have not been consistent between studies. In addition to the favorable properties of these agents for treating coagulation and fibrinolysis, they may improve vascular integrity and strengthen the nasal squamous epithelium.60 However, these agents are associated with significant thromboembolic risks and may result in unfavorable side effects in men, including weight gain, gynecomastia, and loss of libido.

Thrombotic risks of systemic therapies

Antifibrinolytics and antiangiogenics have theoretical thrombotic risks, and certain agents such as bevacizumab have demonstrated elevated thrombotic risks in controlled trials of non-HHT populations. Although randomized studies of tranexamic acid did not demonstrate an increased thrombotic risk in tranexamic acid–treated patients,10,11 those studies were limited to 3 months of follow-up, and concerns remain about the cumulative risk of indefinite daily use of antifibrinolytic therapy. Some reassuring data have come from a recent retrospective study including 24 patients with HHT treated with antifibrinolytic therapy for a median of 13 months, in which none developed VTE.61

Although bevacizumab has demonstrated increased VTE rates in several trials evaluating patients with cancer, highlighting a concern for its long-term use to manage a bleeding disorder, recent data regarding its use in HHT have been reassuring. A study evaluating the safety of bevacizumab in HHT including 69 patients treated for a mean of 11 months reported no VTE events and a single arterial thrombotic event.62 In the InHIBIT-Bleed study of 238 patients, with a median treatment duration of 12 months, VTE occurred in 5 patients (2%).32 Two of the 5 developed VTE 1 to 2 weeks after major joint replacement surgery when bevacizumab had been withheld for over a month before the VTE occurrences (and so the relationship of bevacizumab to VTE was questionable). In addition, bleeding was well controlled by ongoing bevacizumab treatment such that anticoagulation proceeded without difficulty in all 5 patients.

Optimal use and impact of long-term antiangiogenic treatment

Important questions remain regarding the optimal bevacizumab maintenance treatment strategy; the possibility of long-term treatment-emergent adverse events; and the characterization of the impact of bevacizumab on the already dysregulated angiogenic milieu of the patient with HHT. It is unknown whether chronic antiangiogenic therapy positively affects preexisting visceral AVMs or prevents the occurrence of new lesions. It is well documented that discontinuation of bevacizumab leads to eventual rebleeding in most patients with HHT,22 but the bleeding-free interval shows high interpatient variability.63 Presently, both the scheduled “continuous” maintenance strategies (in which regular bevacizumab is given irrespective of symptoms), and the as-needed “intermittent” maintenance strategies (in which reinduction infusions are triggered by recurrent bleeding) are being used by HHT centers, with advantages and disadvantages to each approach.32

An evolving standard of care and future directions

Historically, bleeding in HHT has been managed primarily with hemostatic procedures, with few exceptions. The prominence of anemia management, anticoagulation considerations, and systemic therapies in bleeding management in the new guidelines demonstrate the ongoing evolution in the care of HHT and the pronounced, growing role of hematologists in this multidisciplinary disease. Anemia management is frequently aggressive and complex, anticoagulation often requires expert guidance, and chronic daily antifibrinolytic therapy requires ongoing assessment of thrombotic risk. Antiangiogenics, considered to be “chemotherapy” in many centers despite their targeted, noncytotoxic nature, are generally prescribed by hematologists and hematologist-oncologists. Survey studies have demonstrated that, when used off label to treat HHT, these agents are already primarily being prescribed by hematologists.64,65 Therefore, familiarity and comfort among hematologists with this disease and its novel treatments have never been more important.

Further study is needed for both antiangiogenic therapies and for other potentially promising systemic treatment approaches, such as somatostatin derivatives and immunosuppressants. Successful use of octreotide to manage GI bleeding in HHT was reported in a 2019 prospective case series66 and in 2 case reports.67,68 Tacrolimus, an oral immunosuppressant that may increase endoglin and ALK1 expression,69 is currently being evaluated in human trials after promising results in 2 case reports.70,71 Sirolimus (rapamycin) could have similar therapeutic effects,72 with case reports describing reduced HHT-associated bleeding.73 Angiogenic targets beyond VEGF and VEGF receptors, such as angiopoietin-2 and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway, may also be promising based on findings in preclinical studies.74,75

Multicenter, nationwide US phase III studies are under way or about to begin for 2 antiangiogenic agents after encouraging proof-of-concept studies76,77 : pomalidomide, an immunomodulatory imide drug for treatment of multiple myeloma with fewer long-term toxicity concerns than thalidomide (the PATH-HHT Study; www.clinicaltrials.gov, #NCT03910244), and pazopanib, a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor presently used in solid-tumor malignancies (#NCT03850964). The antiangiogenic agent nintedanib may also be promising in HHT,72,78 and a multicenter French clinical trial evaluating this agent recently began (the EPICURE Study; #NCT03954782). Despite the existing evidence for systemic bevacizumab and thalidomide, no agent has gone through the US Food and Drug Administration approval process, and there remain no Food and Drug Administration–approved agents to treat HHT. Therefore, ongoing investigation into systemic antiangiogenic agents is critical in the development of the therapeutic armamentarium in HHT and in understanding not just short-term outcomes but long-term hemostatic efficacy, safety, and potential impact on the treatment and prevention of visceral AVMs in HHT.

Acknowledgments

The author is a member of the Guidelines Working Group for the Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia.

The author is also a recipient of the Harvard KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training Award and the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award.

Artwork in the visual abstract was reproduced and modified from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/) in accordance with the Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0 (permission given for use and adaptation for any purpose, medium, or format).

Authorship

Contribution: H.A.-S. was responsible for all aspects of the manuscript, from conception to completion.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.A.-S. has been a consultant for Agios, Dova, Argenx, and Rigel and has received research funding from Agios, Dova, and Amgen.

Correspondence: Hanny Al-Samkari, Division of Hematology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Zero Emerson Place, Suite 118, Office 112, Boston, MA 02114; e-mail: hal-samkari@mgh.harvard.edu.