In this issue of Blood, Evens et al highlight critical prognostic factors that drive outcomes across the full continuum of adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma (BL) in the United States.1

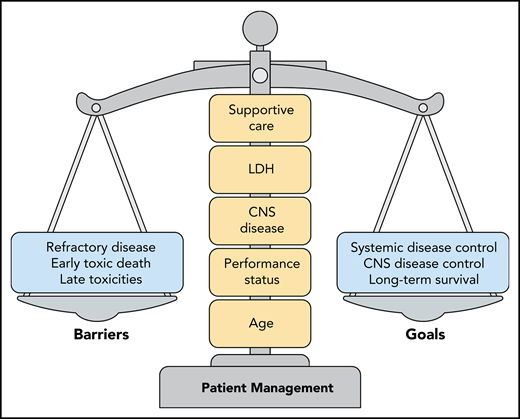

Optimal patient management strategies for adults with BL require a careful evaluation of prognostic factors. The primary barriers to achieving disease control and long-term survival are primary refractory disease, early toxic deaths related to therapy, and the risk of late toxicities. Overemphasis of a single factor can unfavorably tip this delicate balance. The factors that require careful consideration are a combination of patient-related factors (age, performance status), biology-related factors (CNS disease, LDH level), and the resources available for prompt implementation of intensive supportive care.

Optimal patient management strategies for adults with BL require a careful evaluation of prognostic factors. The primary barriers to achieving disease control and long-term survival are primary refractory disease, early toxic deaths related to therapy, and the risk of late toxicities. Overemphasis of a single factor can unfavorably tip this delicate balance. The factors that require careful consideration are a combination of patient-related factors (age, performance status), biology-related factors (CNS disease, LDH level), and the resources available for prompt implementation of intensive supportive care.

These factors include the age and condition of the patient, the extent of tumor burden as measured by the serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, and the presence of central nervous system (CNS) disease. Importantly, these prognostic factors do not include infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although these factors have been recognized as critical determinants of outcome in both children and young adults with BL, this large retrospective series of 641 patients captures the magnitude of barriers preventing the cure of older adults in real-world clinical practice settings, as the 3-year progression-free survival was only 64% in this cohort with a median age of 47 years.2-5 An important, yet underappreciated, factor was where the treatment was delivered. The 12% of patients treated at community hospitals had an inferior overall survival compared with the patients treated at academic hospitals. This observation raises the question of whether the underlying reasons reflect patient referral bias, availability of supportive care resources, lack of expertise in complex disease management, or a combination of factors. The successful management of BL requires prompt implementation of intensive supportive care along with early institution of intensive chemotherapy. The optimal management strategy for individual adult patients requires delicate balancing of all these factors, to achieve long-term survival and avoid early toxic death (see figure). Most prospective clinical trials report high cure rates in adults with BL, often in the 75% to 85% range. However, this series shows that the cure rates are actually much lower in routine practice, suggesting that prospective clinical trials may not adequately capture the patients at highest risk of early death.

BL poses unique management challenges because it is a highly aggressive tumor with a predilection for involvement of extranodal sites, including the bone marrow and/or CNS.6 In addition, because of rapid tumor proliferation, spontaneous tumor lysis syndrome may occur, even before initiation of therapy. Frequent gastrointestinal involvement increases the risk of perforation, and electrolyte disturbances may require hemodialysis early in the treatment course. Hence, early recognition of “possible BL” is a medical emergency that should lead to urgent diagnostic procedures and prompt initiation of aggressive supportive care designed to prevent organ compromise during the first few cycles of therapy. As an example, 27% of the patients in this series had LDH levels >5 times normal which should always prompt suspicion of possible BL. However, because BL represents only 1% to 2% of all lymphomas in adults, these clinical signs may not be fully appreciated by practitioners who are not focused on hematologic malignancies. Indeed, the treatment-related mortality (TRM) in this series was 10%, with the most common causes of death being sepsis (51%), intestinal perforation (15%), and respiratory failure (15%).

The first effective chemotherapy regimens for BL were pediatric: highly dose-intensive combination chemotherapy regimens that included agents that specifically penetrate the CNS.7,8 In general, BL is considered a highly chemotherapy-sensitive tumor, and the complete remission rates of these pediatric regimens are very high. Yet, in this series, the primary refractory disease rate was 14%, suggesting a greater rate of intrinsic chemotherapy resistance than is commonly appreciated. Second, active CNS involvement is a known poor prognostic marker across all regimens used for BL. The rate of involvement at diagnosis is ∼10% in most prospective clinical trials. In this series, the CNS involvement rate was 19%, including 3% of patients with brain parenchymal involvement, and was more common in patients with HIV infection (P < .001). These data support the notion that agents with good CNS penetration are critical. Further, the high rate of primary refractory disease suggest that chemotherapy agents alone may be inadequate to overcome treatment resistance.

Although pediatric regimens are highly effective in children and young adults, older patients often cannot tolerate these regimens. In this series, the TRM was only 2% in patients aged <40 years of age, but jumped to 16% in patients aged ≥60 years. The lower intensity regimen, dose-adjusted etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) has recently been shown to be highly effective in adults of all ages with BL. Careful examination for occult CNS disease is critical, because a risk-adapted approach is used with this regimen to treat and prevent CNS disease. Despite lower dose intensity, patients with active CNS disease treated with DA-EPOCH-R remain at risk for early toxic death caused by sepsis and multisystem organ failure.2 Finally, all patients regardless of age remain at risk for late toxicities, including secondary malignancies.9 In this series, 25 (6%) cases of secondary myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia were observed after a median of only 45 months and were almost exclusively observed after highly dose-intensive regimens.

In summary, although this important dataset highlights the critical prognostic factors across the full spectrum of adult patients with BL, only prospective clinical trials can inform the selection of the optimal treatment regimen. Unsurprisingly, the patients treated with lower intensity regimens in this study were older and had a worse performance status than did those treated with highly dose-intensive regimens. Outcomes in adults with BL have significant room for improvement, because of intrinsic treatment resistance and risk of early toxic death. These factors must be carefully balanced when personalizing management strategies. If one is considering highly dose-intensive regimens, then both early and late toxicities should be part of the calculus. If one is considering lower intensity regimens, careful examination of the cerebral spinal fluid by flow cytometry should be performed to avoid undertreatment of CNS disease. The balance of risk factors should be the same in HIV+ patients compared with those without HIV.2,10 Finally, prompt recognition of possible BL represents a medical emergency that requires rapid diagnosis; intensive supportive care is mandatory for all patients. Practitioners at community hospitals should consider referral to an academic tertiary hospital if they lack sufficient expertise or adequate supportive care resources.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal