In this issue of Blood, Sarkozy et al1 demonstrate that the genomic profile of B-cell lymphomas with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), often referred as gray zone lymphomas (GZLs), differs according to their topographic location in anterior mediastinum (thymic niche) or extramediastinal regions.

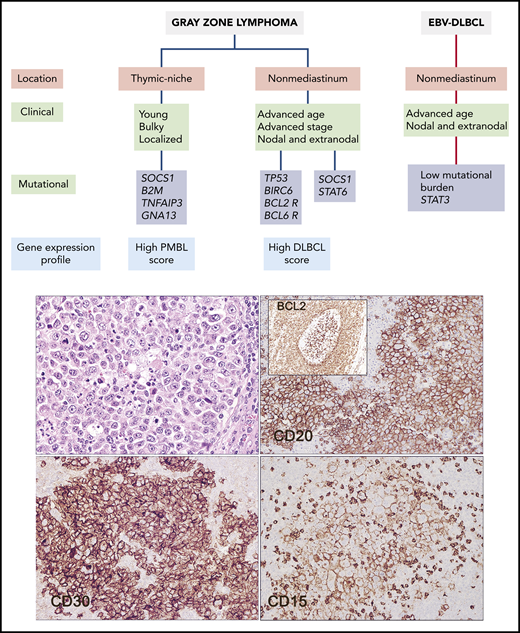

Clinical, biological, and pathological features of GZL and related entities. GZL should be distinguished from EBV-positive DLBCL, which may show similar morphological features. The current study provides new data that more clearly separate GZL arising in the thymic niche from those arising in extramediastinal sites. The clinical case illustrated arose in an inguinal lymph node in a 54-year-old woman. It has features of GZL, being positive for CD20, CD30, and CD15 (hematoxylin & eosin and immunohistochemical staining for the indicated markers). The tumor was positive for BCL2 rearrangement. Notably, a focus of in situ follicular neoplasia was identified in “reactive follicles” adjacent to the tumor mass (inset). The patient relapsed 2 years later with follicular lymphoma, shown to be clonally related to the nonmediastinal GZL.

Clinical, biological, and pathological features of GZL and related entities. GZL should be distinguished from EBV-positive DLBCL, which may show similar morphological features. The current study provides new data that more clearly separate GZL arising in the thymic niche from those arising in extramediastinal sites. The clinical case illustrated arose in an inguinal lymph node in a 54-year-old woman. It has features of GZL, being positive for CD20, CD30, and CD15 (hematoxylin & eosin and immunohistochemical staining for the indicated markers). The tumor was positive for BCL2 rearrangement. Notably, a focus of in situ follicular neoplasia was identified in “reactive follicles” adjacent to the tumor mass (inset). The patient relapsed 2 years later with follicular lymphoma, shown to be clonally related to the nonmediastinal GZL.

These findings support the idea that GZLs originating in different sites differ in their pathogenic mechanisms and may correspond to different entities. The study further identifies differences between all forms of GZL and Epstein Barr virus (EBV)–positive large B-cell lymphomas, suggesting that despite some overlapping morphological features, most EBV-driven B-cell lymphomas correspond to a different disease.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification recognizes the existence of GZL as a tumor with overlapping clinical, morphological, and phenotypic features between CHL and DLBCL. Since we have learned that CHL, and also nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, are B-cell neoplasms, we have better understood the coexistence of Hodgkin lymphoma with nearly all forms of mature B-cell neoplasia.2 A prime example, CHL, nodular sclerosis (NS) subtype, and primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL), may occur sequentially or as composite lymphoma in the same location and have been shown to be clonally related.3 This observation led to the logical conclusion that some lymphomas may show hybrid features, exhibiting morphological and phenotypic features not falling neatly into CHL or B-cell lymphoma (ie, GZL). The close relationship of GZL with entities on both sides of the spectrum had been emphasized by previous molecular and genetic studies that reported the presence of CIITA translocations and amplifications of REL (2p16.1) and JAK2 (9p24.1) in GZL as well as in CHL and PMBL.4 Global methylation and gene expression profiling studies also revealed that the features of GZL are also intermediate between CHL and PMBL.5,6

Despite these advances in understanding the biology of GZL, the precise diagnosis, clinical significance and management are challenging. The current definition of GZL in the WHO classification accepts tumors originating in both mediastinal and nonmediastinal sites, although it notes that nonmediastinal GZL occurs more often in older patients.4 Some studies have included EBV-positive and negative cases in the GZL category,7 but the assumption has been that EBV-positive variants are exceptionally rare.8

The current genomic study of Sarkozy et al illuminates some of these uncertainties. The authors performed whole-exome sequencing in 21 GZL and 7 EBV-positive DLBCLs with prominent inflammatory background (polymorphic EBV-DLBCL), which may resemble GZL, followed by target sequencing of 217 genes in 29 GZL and 13 polymorphic EBV-DLBCLs. Interestingly, the mutational and genetic profile of GZL correlated with the topographic location of the tumors. Tumors in the anterior mediastinum (thymic niche) had a genomic profile close to that of CHL and PMBL, with frequent mutations in genes of the JAK-STAT (SOCS1), immunomodulation (B2M), and nuclear factor (NF-κB) (TNFAIP3 and NFKBIA) pathways, and lacked BCL2 or BCL6 translocations. Notably, these mutations were absent or uncommon in extramediastinal GZL that instead carried mutations in apoptotic regulators (TP53, BCL2, and BIRC6) and had BCL2 and BCL6 translocations. Comparing gene expression signatures that define PMBL and DLBCL, mediastinal GZL showed greater similarity to PMBL, while nonmediastinal GZLs were closer to DLBCLs. Although limited by the smaller number of cases, nonmediastinal GZLs are likely to be heterogeneous, with a subset of cases exhibiting mutations in TP53 and genes related to germinal center–derived DLBCL (KMT2D, CREBBP, BCL2) and BCL2 or BCL6 translocations, whereas a second subgroup lacked most of these alterations but had STAT6 and SOCS1 missense mutations. The genomic profile of polymorphic EBV-DLBCL further departed from both mediastinal and nonmediastinal GZL by carrying lower global burden of coding mutations and mutations in STAT3 but lacking mutations in NF-κB, TP53, and B2M/HLA-B genes (see figure).

The findings by Sarkozy et al have conceptual and practical implications and open intriguing questions deserving future exploration. The mutational profile described here further emphasizes the close relationship of mediastinal GZL with NS CHL and PMBL, but extramediastinal GZLs appear to arise by different pathways. Their genomic profile suggests that they may be closer to the various molecular subsets of DLBCL.

The current study also supports the view that EBV positivity should point to other EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorders. Many EBV-related conditions, including infectious mononucleosis, mucocutaneous ulcer, and even peripheral T-cell lymphomas, may contain Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg-like cells and often elicit a prominent inflammatory background. Intriguingly, 5 polymorphic EBV-DLBCLs in this study were diagnosed in the mediastinum and lacked the mutations found in nonmediastinal cases. The proper categorization of these cases is uncertain, but it must be remembered that EBV can be positive in many B-cell neoplasms, including NS CHL. Thus, EBV-positive mediastinal GZL may indeed exist.8 The number was limited, and the panel used for target sequence may not have captured the spectrum of mutations in EBV-driven lymphomas. Extended genomic analysis of EBV-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders may assist in a better understanding of these rare cases.

The term GZL has been used for lymphomas with hybrid morphological and phenotypic features between 2 well-defined entities, particularly CHL and DLBCL, but also for lymphomas with intermediate features between nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma and T-cell/histiocytic-rich large B-cell lymphoma or EBV-positive CHL and EBV-positive DLBCL, among others.9 The study by Sarkozy et al shows that not all GZLs, and even those intermediate between CHL and DLBCL, correspond to the same biological category. GZL may be as heterogeneous as the spectrum of B-cell neoplasia. We need to better understand the pathological and molecular plasticity of these neoplasms and refine more precisely the use of the term GZL to avoid lumping together tumors that may correspond to different entities. The clinical management of GZL, and in particular mediastinal GZL, is still not well defined.10 A better understanding of the underlying biology is crucial in our quest to improve the therapy of this diverse spectrum of tumors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal