Key Points

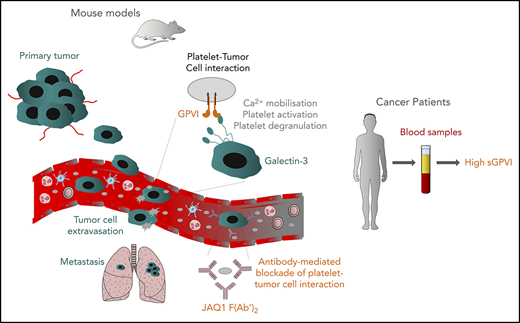

Platelet GPVI promotes tumor cell extravasation and metastasis through binding to galectin-3.

Pharmacological blockade of GPVI inhibits platelet–tumor cell interaction and tumor metastasis.

Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that platelets play a predominant role in colon and breast cancer metastasis, but the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Glycoprotein VI (GPVI) is a platelet-specific receptor for collagen and fibrin that triggers platelet activation through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) signaling and thereby regulates diverse functions, including platelet adhesion, aggregation, and procoagulant activity. GPVI has been proposed as a safe antithrombotic target, because its inhibition is protective in models of arterial thrombosis, with only minor effects on hemostasis. In this study, the genetic deficiency of platelet GPVI in mice decreased experimental and spontaneous metastasis of colon and breast cancer cells. Similar results were obtained with mice lacking the spleen-tyrosine kinase Syk in platelets, an essential component of the ITAM-signaling cascade. In vitro and in vivo analyses supported that mouse, as well as human GPVI, had platelet adhesion to colon and breast cancer cells. Using a CRISPR/Cas9-based gene knockout approach, we identified galectin-3 as the major counterreceptor of GPVI on tumor cells. In vivo studies demonstrated that the interplay between platelet GPVI and tumor cell–expressed galectin-3 uses ITAM-signaling components in platelets and favors the extravasation of tumor cells. Finally, we showed that JAQ1 F(abʹ)2-mediated inhibition of GPVI efficiently impairs platelet–tumor cell interaction and tumor metastasis. Our study revealed a new mechanism by which platelets promote the metastasis of colon and breast cancer cells and suggests that GPVI represents a promising target for antimetastatic therapies.

Introduction

Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer-related death and represents a major challenge in patient care.1 Although many anticancer therapies have been developed, the prognosis remains unfavorable once metastatic dissemination has occurred.2 Tumor metastasis develops in sequential steps: detachment of tumor cells from the primary tumor and intravasation into the blood or lymphatic circulation, transport within the bloodstream, extravasation, and colonization of distant sites and growth of metastases.1 Although some mechanisms reflect tumor cell–autonomous processes, most require the interaction of tumor cells with blood cells, including myeloid cells and platelets.1,3,4

The interaction of tumor cells with platelets enhances their survival in the bloodstream and facilitates tumor metastasis.5,6 Platelets shield tumor cells against mechanical destruction by hemodynamic shear stress and lysis by natural killer cells.7 Activated platelets can release cytokines, growth factors, and secondary mediators, thereby enhancing tumor cell invasiveness, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, extravasation, and promotion of angiogenesis and vascular remodelling.3,8-11 The presence of tumor cell–activated platelets in the bloodstream can predispose cancer patients to thrombotic events, further increasing tumor cell malignancy.4,12 Consistently, thrombocytosis, tumor cell–induced platelet aggregation, and high plasma fibrinogen concentration and D-dimer levels are associated with a poor prognosis of solid cancers, such as breast, colon, and ovarian cancers, implicating the contribution of platelets in the progression of the disease.4,13-16 It has been shown that platelet-expressed membrane receptors, such as P-selectin, integrin αIIbβ3, integrin α6β1, and C-type lectin-like receptor-2, contribute to the interaction between platelets and tumor cells, endothelial cells, and fibrin, thereby influencing cancer progression and metastasis.5,17-21

Glycoprotein (GP) VI (GPVI) is a receptor for collagen, laminin, and fibrin, which regulate multiple platelet functions, such as adhesion, aggregation, and procoagulant activity.22-27 After ligand binding, GPVI forms receptor clusters on the platelet surface. Src kinase–dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) of the GPVI-associated FcRγ chain induces a signaling pathway involving Src and Syk tyrosine kinases, which further phosphorylate and activate the linker of activated T-cell signalosome and phospholipase-Cγ2.26,28 GPVI has been proposed to be a potentially safe antithrombotic target based on the observations that its blockade reduces arterial thrombosis without impairing hemostasis.29-32 Besides its central role in thrombosis, GPVI is involved in the maintenance of vascular integrity under inflammatory conditions.28,33-37 The role of this ITAM-containing receptor in tumor metastasis has not been well investigated, and only a few studies are currently available that assessed this process. In experimental metastatic approaches, GPVI deficiency in mice leads to a decreased number of metastatic foci of B16-F10 and Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells.38 In addition, we recently showed that functional inhibition of GPVI induces bleeding and tumor hemorrhage, thereby increasing the intratumoral efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs within primary tumors.39 However, molecular mechanisms underlying the role of GPVI in tumor metastasis has not been elucidated.

In our study, we showed that platelets promote metastasis of colon and breast cancer cells through an interaction between platelet GPVI and its counterreceptor galectin-3. Our findings demonstrated that platelet GPVI and galectin-3 expressed on tumor cells may represent a new therapeutic target or axis for combating tumor metastasis.

Details of materials and methods are described in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 and BALB/c1 mice were obtained from Janvier (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). Gp6−/−, Unc13d−/−, and Sykfl/fl, Pf4-cre+/− (Syk−/−) mice lacking Syk kinase in megakaryocyte/platelet lineage and their control littermates Sykfl/fl, Pf4-cre−/− (Syk+/+) have been described previously.40-42 Lgals3−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and crossed with Gp6−/− mice. All the indicated genetically modified mouse strains were established on a C57BL/6 background. Animal procedures described in this study were approved by the Regional Administration of Unterfranken (Lower District), Würzburg, Germany. The experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental and spontaneous models of tumor metastasis

MC38 and MC38-CEA colon and AT3 and E0771 breast cancer cell lines are syngeneic to C57BL/6 and 4T1 breast cancer lines, respectively, on a BALB/c1 background,. To study experimental metastasis, we injected 1 × 106 MC38 or MC38-CEA; 5 × 105 E0771 or AT-3; or 3 × 105 4T1 parental, control, or Lgals3-knockout cells into the lateral tail vein. Mice were euthanized at day 15 after injection, and the number of metastases was determined by counting the metastatic foci on the lung surface. To study spontaneous metastasis, we injected 5 × 105 MC38 or MC38-CEA colon or 3 × 105 AT-3 breast cancer cells subcutaneously or into a mammary fat pad of 8-week-old male and female virgin mice, respectively, and the animals were euthanized at day 30 after injection. Tumor volumes were measured with Vernier calipers and determined with the following calculation: V = (width)2 × length/2. In some experiments, wild-type (WT) mice were injected with 100 µg JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody, 1 mg/kg acetylsalicylic acid (ASA [aspirin]; Aspisol), or 4 mg/kg GPVI-Fc43 or were depleted of neutrophils by using the 1A8 antibody (5 mg/kg; BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany).

Results

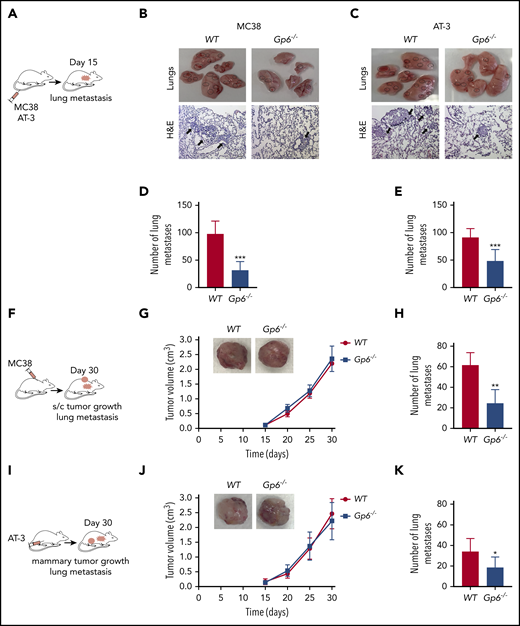

GPVI deficiency decreases metastasis of colon and breast cancer cells

To directly test the hypothesis that GPVI has a role in the metastasis of colon and breast cancer cells, we injected MC38 colon cancer cells and AT-3 breast cancer cells into the tail vein of syngeneic WT and GPVI-deficient (Gp6−/−) mice and determined the extent of lung metastasis after 15 days (Figure 1A-E). Although both MC38 and AT-3 cell lines established pulmonary metastatic foci, they were significantly decreased in Gp6−/− mice compared with WT controls (Figure 1D-E; supplemental Figure 1A-B).

Lack of platelet GPVI inhibits tumor metastasis. (A) Schematic of a lung colonization assay after IV injection of MC38 colon (B,D) or AT-3 breast (C,E) cancer cells in WT and Gp6−/− mice. (B,C) Representative photographs (top) and hematoxylin-eosin–stained sections (bottom) obtained from the lungs of MC38 and AT-3–injected WT and Gp6−/− mice. (B,C) Dashed black circles and arrows indicate metastatic nodules. The bar represents 200 µm. (D,E) Bar graphs representing the number of lung metastases in MC38 (D)- and AT-3 (E)–injected WT and Gp6−/− mice. Mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 5 (D) and n = 7 (E) mice per group. ***P < .001, by unpaired Student t test. (F,I) Schematic of mouse heterotopic and orthotopic metastasis assays. MC38 (F-H) and AT-3 (I-K) tumor cells were injected subcutaneously or into the fourth mammary fat pad of WT and Gp6−/− mice, and the volume of subcutaneous (G) or mammary (J) tumors and the number of lung metastases was determined. (G,J) Kinetic of primary tumor growth in WT and Gp6−/− mice. Mean ± SD; n = 5 (G) and n = 8 (J) per group. (H,K) The number of spontaneous lung metastases in MC38 (H)- and AT-3 (K)–injected WT and Gp6−/− mice. Mean ± SD; n = 6 (H) and n = 8 (K) mice per group. *P < .05; **P < .01, by Mann-Whitney test.

Lack of platelet GPVI inhibits tumor metastasis. (A) Schematic of a lung colonization assay after IV injection of MC38 colon (B,D) or AT-3 breast (C,E) cancer cells in WT and Gp6−/− mice. (B,C) Representative photographs (top) and hematoxylin-eosin–stained sections (bottom) obtained from the lungs of MC38 and AT-3–injected WT and Gp6−/− mice. (B,C) Dashed black circles and arrows indicate metastatic nodules. The bar represents 200 µm. (D,E) Bar graphs representing the number of lung metastases in MC38 (D)- and AT-3 (E)–injected WT and Gp6−/− mice. Mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 5 (D) and n = 7 (E) mice per group. ***P < .001, by unpaired Student t test. (F,I) Schematic of mouse heterotopic and orthotopic metastasis assays. MC38 (F-H) and AT-3 (I-K) tumor cells were injected subcutaneously or into the fourth mammary fat pad of WT and Gp6−/− mice, and the volume of subcutaneous (G) or mammary (J) tumors and the number of lung metastases was determined. (G,J) Kinetic of primary tumor growth in WT and Gp6−/− mice. Mean ± SD; n = 5 (G) and n = 8 (J) per group. (H,K) The number of spontaneous lung metastases in MC38 (H)- and AT-3 (K)–injected WT and Gp6−/− mice. Mean ± SD; n = 6 (H) and n = 8 (K) mice per group. *P < .05; **P < .01, by Mann-Whitney test.

Models of spontaneous metastasis encompass early and late stages of cancer progression, involving cell implantation, at either a heterotopic or orthotopic site, to form a primary tumor that may subsequently disseminate.44,45 The effect of GPVI deficiency on spontaneous metastasis was determined by the subcutaneous injection of MC38 cells (Figure 1F), representing a heterotopic colon cancer model. In another set of experiments, AT-3 cells were injected into the mammary fat pad (orthotopic breast cancer model; Figure 1I), and tumor size was evaluated every 5 days. We found that both cell types established primary tumors with similar kinetics in Gp6−/− mice compared with the WT controls (Figure 1G, J). In contrast, the number of spontaneously formed lung metastases was reduced in Gp6−/− mice by 2.5- and 1.8-fold, respectively, compared with the WT controls (Figure 1H, K; supplemental Figure 1C-D).

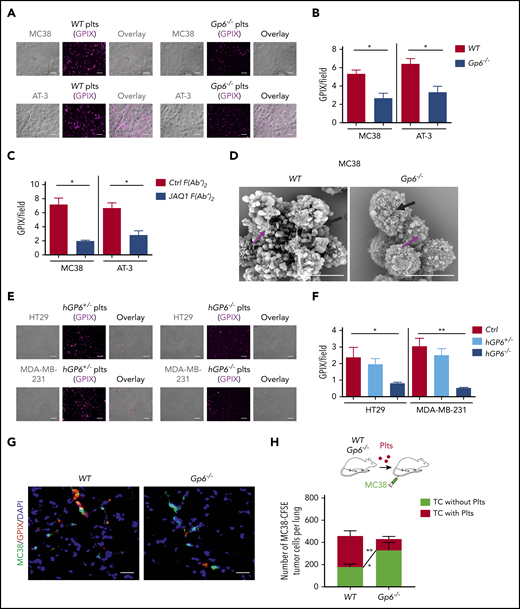

GPVI contributes to platelet–tumor cell interaction

The first hours of a tumor cell in the bloodstream are critical for its survival and successful metastasis, and platelets are the first cells to interact with circulating tumor cells.4,6 To evaluate whether GPVI is involved in platelet–tumor cell interaction, platelets were allowed to adhere to tumor cells in vitro under static conditions. Gp6−/− mouse platelets showed reduced recruitment to colon (MC38), breast cancer (AT-3), and LLC cells compared with WT control platelets (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 2A). Similar results were obtained when GPVI function was blocked in WT platelets by adding F(ab′)2 fragments of the JAQ1 antibody (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 2B). This interaction was also visualized in cell suspension by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), confirming that adhesion of GPVI-deficient platelets to tumor cells was strongly inhibited (Figure 2D).

Genetic deficiency or antibody-mediated blockade of GPVI impairs platelet–tumor cell interaction. Platelet adhesion to tumor cells was quantified based on the fluorescence detection of anti-GPIX–labeled platelets, as described in “Materials and methods.” (A-B) Washed WT or Gp6−/− mouse platelets (Plts) were allowed to adhere to MC38 colon and AT-3 breast cancer cells. The bar represents 20 µm. (C) Similar experiments were performed with WT mouse platelets treated with JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. (D) Representative SEM images of WT and Gp6−/− mouse platelets adhering to MC38 tumors cells. Washed mouse platelets were mixed with MC38 colon cancer cells (100 platelets/cell), incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, and then analyzed by SEM. The bar represents 8 μm. Arrows indicate platelets (magenta) and tumor cells (black). (E-F) Washed human platelets were isolated from patients carrying the heterozygous (GP6+/−) or homozygous (GP6−/−) mutation in the GP6 gene or from healthy donors and coincubated with human HT29 colon and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Shown are representative images of GP6+/− and GP6−/− platelets adhering to HT29 and MDA-MB-231 cells. The bar represents 20 µm. (B-C,F) Quantification of the fluorescence signal corresponding to the number of mouse (B-C) and human (F) platelets adhering to tumor cells. (B-C) Mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (F) Mean ± SD; Ctrl (healthy donor), n = 3; GP6+/−, n = 2; and GP6−/−, n = 3. *P < .05; **P < .01, by unpaired Student t test. (G,H) Experimental design: thrombocytopenic mice were transfused with Cy3-conjugated anti-GPIX-labeled WT or Gp6−/− platelets (red) and CFSE-labeled MC38 tumor cells (green). One hour after injection, mice were euthanized, the lungs were collected, and the colocalization of MC38 tumor cells with platelets was determined by confocal microscopy. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 20 µm. (H) Quantification of the number of tumor cells surrounded or not by platelets. Mean ± SD, n = 4 mice per group, tumor cells (TC) without Plts WT vs Gp6−/−, *P < .05; TC with Plts WT vs Gp6−/−; **P < .01, by 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test.

Genetic deficiency or antibody-mediated blockade of GPVI impairs platelet–tumor cell interaction. Platelet adhesion to tumor cells was quantified based on the fluorescence detection of anti-GPIX–labeled platelets, as described in “Materials and methods.” (A-B) Washed WT or Gp6−/− mouse platelets (Plts) were allowed to adhere to MC38 colon and AT-3 breast cancer cells. The bar represents 20 µm. (C) Similar experiments were performed with WT mouse platelets treated with JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. (D) Representative SEM images of WT and Gp6−/− mouse platelets adhering to MC38 tumors cells. Washed mouse platelets were mixed with MC38 colon cancer cells (100 platelets/cell), incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, and then analyzed by SEM. The bar represents 8 μm. Arrows indicate platelets (magenta) and tumor cells (black). (E-F) Washed human platelets were isolated from patients carrying the heterozygous (GP6+/−) or homozygous (GP6−/−) mutation in the GP6 gene or from healthy donors and coincubated with human HT29 colon and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Shown are representative images of GP6+/− and GP6−/− platelets adhering to HT29 and MDA-MB-231 cells. The bar represents 20 µm. (B-C,F) Quantification of the fluorescence signal corresponding to the number of mouse (B-C) and human (F) platelets adhering to tumor cells. (B-C) Mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (F) Mean ± SD; Ctrl (healthy donor), n = 3; GP6+/−, n = 2; and GP6−/−, n = 3. *P < .05; **P < .01, by unpaired Student t test. (G,H) Experimental design: thrombocytopenic mice were transfused with Cy3-conjugated anti-GPIX-labeled WT or Gp6−/− platelets (red) and CFSE-labeled MC38 tumor cells (green). One hour after injection, mice were euthanized, the lungs were collected, and the colocalization of MC38 tumor cells with platelets was determined by confocal microscopy. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 20 µm. (H) Quantification of the number of tumor cells surrounded or not by platelets. Mean ± SD, n = 4 mice per group, tumor cells (TC) without Plts WT vs Gp6−/−, *P < .05; TC with Plts WT vs Gp6−/−; **P < .01, by 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test.

Previously, Matus et al46 and Onselaer et al47 described families with a loss-of-function mutation of GPVI and heterozygous relatives (hGP6+/−). We investigated the adhesion efficiency of control, hGP6+/−, and hGP6−/− human platelets to human colorectal HT29 and breast MDA-MB-231 cancer cells and found that hGP6−/− platelet adhesion to the tumor cells was markedly reduced (Figure 2E-F).

Next, platelet interaction with tumor cells was determined in vivo. Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled tumor cells and platelets labeled with Cy3-conjugated anti-GPIX antibody derivative were injected into the tail vein of thrombocytopenic mice, and the lungs were collected after 1 hour (Figure 2G). Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of lung sections revealed that the number of tumor cells covered by platelets was markedly reduced in mice transfused with Gp6−/− platelets compared with those transfused with WT platelets (Figure 2H), suggesting an essential role of GPVI in platelet–tumor cell interaction.

Galectin-3 binding to GPVI supports platelet–tumor cell interaction

Galectins induce platelet adhesion and aggregation,48 and upregulation of galectins is a hallmark of various malignancies.49,50 Galectin-3 contains a collagen-like domain and is highly expressed by various cancer cells,51,52 including cell lines used for our studies (supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, we hypothesized that galectin-3 initiates platelet–tumor cell binding through interactions with the collagen-binding site of GPVI. First, we modeled the GPVI–galectin-3 binding using already available crystal structures53,54 and bioinformatics tools55,56 and found that the structure of galectin-3 is preferentially shifted toward the B chain of GPVI by covering a larger interaction area on the surface of protein, including more interaction residues, compared with the A chain (supplemental Figure 4; supplemental Table 1). According to the umbrella sampling methodology,57 binding affinity was estimated as ΔGbind = −5.91 kcal/mol and dissociation constant (KD) = 44.89 μM (Figure 3A) and compared with the binding affinity between GPVI and collagen types I (ΔGbind ≈ −6.91 kcal/mol and KD = 8.1 ± 1.2 μM) and III (ΔGbind ≈ −6.6 kcal/mol and KD = 13.8 ± 2.5 μM) from a previous study.58

Galectin-3 expressed on tumor cells supports GPVI-dependent platelet adhesion. (A) Prediction of binding affinity between galectin-3 (red) and GPVI (blue). Graphs correspond to ΔGbind = −5.91 kcal/mol and KD = 44.89 μM, respectively. Potential of mean force (PMF) values were extracted by the weighted histogram analysis method, which yields the binding free energy (ΔGbind) for the binding and unbinding processes. The ΔGbind value was calculated as the difference between the highest and lowest values of the PMF curve. The KD of the protein–protein complex was calculated from the ΔGbind value according to the following equation: KD = exp(ΔGbind/R · T), where R (gas constant) is 1.98 cal(mol·K)−1 and T (room temperature) is 298.15 Kelvins (K). The Boltzmann (sigmoidal) nonlinear fitting [R2 = 0.85; RMSE (root mean square error) = 0.67; RSS (residual sum of squares) = 88.31] of the data set is shown to assess the PMF elevation pattern with the increase of reaction coordinate (ξ), using the scaled Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm with tolerance = 0.0001. (B-C) Knockout of the galectin-3 gene (Lgals3 KO) expression in MC38 and AT-3 cells. (B) Galectin-3 mRNA expression was determined by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and normalized with a messenger RNA level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 4 separate cell culture experiments; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of galectin-3 (Lgals3 KO) knockout MC38 and AT-3 cells or cells expressing galectin-3 gene (Ctrl: control), with an anti-galectin-3 antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 20 µm. (D-E) Quantification of the fluorescence signal corresponding to the amount of WT (D-E) and Gp6−/− (D) mouse platelets adhering to (D-E) MC38 and AT-3 Ctrl and Lgals3 KO cancer cells. (D) Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group. MC38 Ctrl/WT platelets (plts; 3.607 ± 0.6198); MC38 Ctrl/Gp6−/− plts (1.593 ± 0.2774); MC38 Lgals3 KO/WT plts (1.6 ± 0.2402); and MC38 Lgals3 KO/Gp6−/− plts (1.423 ± 0.1665). AT-3 Ctrl/WT plts (5.37 ± 0.3005); AT-3 Ctrl/Gp6−/− plts (1.897 ± 0.4944); AT-3 Lgals3 KO/WT plts (1.817 ± 0.586); and AT-3 Lgals3 KO/Gp6−/− plts (1.683 ± 0.486). ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (E) Similar experiments were performed with WT platelets in the absence or presence of JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group. MC38 Ctrl/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (5.017 ± 0.2055); MC38 Ctrl/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.437 ± 0.493); MC38 Lgals3 KO/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (2.757 ± 0.2139); and MC38 Lgals3 KO/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.273 ± 0.4366). AT-3 Ctrl/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (5.313 ± 0.5326); AT-3 Ctrl/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.38 ± 1.057); AT-3 Lgals3 KO/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (1.967 ± 0.2259); and AT-3 Lgals3 KO/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.01 ± 0.1825). **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (F,H) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of mouse (WT and Gp6−/−) (F) and human (H; top; Ctrl, healthy subject; hGP6+/−, human patient with heterozygous mutation; and hGP6−/−, human patient with homozygous mutation) platelets adhering to recombinant galectin-3 under static conditions. The bar represents 20 µm. (H, bottom). Representative immunofluorescence images of GPVI-Fc–conjugated fluorescent microspheres adhering on galectin-1–, galectin-3– and collagen I–coated surfaces. (G,I) Quantification of adherent mouse (G) and human (I) platelets under static conditions on galectin-3. (G) Mean ± SD; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (I) Mean ± SD. Ctrl, n = 5; hGP6+/−, n = 2; and hGP6−/−, n = 3. (J) Binding of dimeric GPVI to galectin-3. GPVI–Fc-Alexa-488 was added to microwells coated with galectin-1, galectin-3, collagen I, or bovine serum albumin (BSA). Protein binding was assessed by measuring the fluorescence intensity (FI) at 488 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 4 separate experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Galectin-3 expressed on tumor cells supports GPVI-dependent platelet adhesion. (A) Prediction of binding affinity between galectin-3 (red) and GPVI (blue). Graphs correspond to ΔGbind = −5.91 kcal/mol and KD = 44.89 μM, respectively. Potential of mean force (PMF) values were extracted by the weighted histogram analysis method, which yields the binding free energy (ΔGbind) for the binding and unbinding processes. The ΔGbind value was calculated as the difference between the highest and lowest values of the PMF curve. The KD of the protein–protein complex was calculated from the ΔGbind value according to the following equation: KD = exp(ΔGbind/R · T), where R (gas constant) is 1.98 cal(mol·K)−1 and T (room temperature) is 298.15 Kelvins (K). The Boltzmann (sigmoidal) nonlinear fitting [R2 = 0.85; RMSE (root mean square error) = 0.67; RSS (residual sum of squares) = 88.31] of the data set is shown to assess the PMF elevation pattern with the increase of reaction coordinate (ξ), using the scaled Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm with tolerance = 0.0001. (B-C) Knockout of the galectin-3 gene (Lgals3 KO) expression in MC38 and AT-3 cells. (B) Galectin-3 mRNA expression was determined by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and normalized with a messenger RNA level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 4 separate cell culture experiments; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of galectin-3 (Lgals3 KO) knockout MC38 and AT-3 cells or cells expressing galectin-3 gene (Ctrl: control), with an anti-galectin-3 antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 20 µm. (D-E) Quantification of the fluorescence signal corresponding to the amount of WT (D-E) and Gp6−/− (D) mouse platelets adhering to (D-E) MC38 and AT-3 Ctrl and Lgals3 KO cancer cells. (D) Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group. MC38 Ctrl/WT platelets (plts; 3.607 ± 0.6198); MC38 Ctrl/Gp6−/− plts (1.593 ± 0.2774); MC38 Lgals3 KO/WT plts (1.6 ± 0.2402); and MC38 Lgals3 KO/Gp6−/− plts (1.423 ± 0.1665). AT-3 Ctrl/WT plts (5.37 ± 0.3005); AT-3 Ctrl/Gp6−/− plts (1.897 ± 0.4944); AT-3 Lgals3 KO/WT plts (1.817 ± 0.586); and AT-3 Lgals3 KO/Gp6−/− plts (1.683 ± 0.486). ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (E) Similar experiments were performed with WT platelets in the absence or presence of JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group. MC38 Ctrl/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (5.017 ± 0.2055); MC38 Ctrl/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.437 ± 0.493); MC38 Lgals3 KO/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (2.757 ± 0.2139); and MC38 Lgals3 KO/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.273 ± 0.4366). AT-3 Ctrl/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (5.313 ± 0.5326); AT-3 Ctrl/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.38 ± 1.057); AT-3 Lgals3 KO/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (1.967 ± 0.2259); and AT-3 Lgals3 KO/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.01 ± 0.1825). **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (F,H) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of mouse (WT and Gp6−/−) (F) and human (H; top; Ctrl, healthy subject; hGP6+/−, human patient with heterozygous mutation; and hGP6−/−, human patient with homozygous mutation) platelets adhering to recombinant galectin-3 under static conditions. The bar represents 20 µm. (H, bottom). Representative immunofluorescence images of GPVI-Fc–conjugated fluorescent microspheres adhering on galectin-1–, galectin-3– and collagen I–coated surfaces. (G,I) Quantification of adherent mouse (G) and human (I) platelets under static conditions on galectin-3. (G) Mean ± SD; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (I) Mean ± SD. Ctrl, n = 5; hGP6+/−, n = 2; and hGP6−/−, n = 3. (J) Binding of dimeric GPVI to galectin-3. GPVI–Fc-Alexa-488 was added to microwells coated with galectin-1, galectin-3, collagen I, or bovine serum albumin (BSA). Protein binding was assessed by measuring the fluorescence intensity (FI) at 488 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 4 separate experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

To confirm our bioinformatics result experimentally, we deleted galectin-3 expression in colon (MC38) and breast cancer (AT-3, 4T1, and E0771) cell lines using a CRISPR/Cas9 strategy (Figure 3B-C; supplemental Figure 5). Interestingly, the interaction of WT platelets with galectin-3–deficient MC38, AT-3, 4T1, and E0771 cancer cells was markedly reduced compared with the respective control tumor cells (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 5), indicating a crucial role of galectin-3 in mediating platelet–tumor cell interactions. Of note, adhesion of WT platelets to galectin-3–deficient cancer cells was similar to the adhesion level of Gp6−/− platelets to galectin-3–expressing cancer cells. Furthermore, no additive inhibitory effect was observed when Gp6−/− platelets were added to galectin-3–deficient cancer cells (Figure 3D). Similar results were obtained when GPVI function was blocked in WT platelets by adding F(abʹ)2 fragments of the JAQ1 antibody (Figure 3E). Next, WT and Gp6−/− platelets were allowed to adhere to a recombinant galectin-3 protein under static conditions. We found that Gp6−/− platelet adhesion to the galectin-3–coated surface decreased significantly compared with that of the WT controls (Figure 3F-G). A similar inhibition was obtained using GPVI-depleted platelets isolated from JAQ1-IgG–injected mice32 (Figure 3F-G) or using GPVI-deficient human platelets (Figure 3H-I). Of note, GPVI deficiency did not reduce platelet adhesion on recombinant galectin-1, which has a structure similar to galectin-3 but lacks the collagen-like domain (supplemental Figure 6). Next, we used fluorescent microspheres conjugated to a soluble dimeric form of GPVI (GPVI-Fc)43 in static adhesion assays and found a specific interaction with galectin-3, but not with galectin-1 (Figure 3H). Similar results were obtained by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Figure 3J), indicating that the collagen-like domain of galectin-3 is involved in the interaction with GPVI.

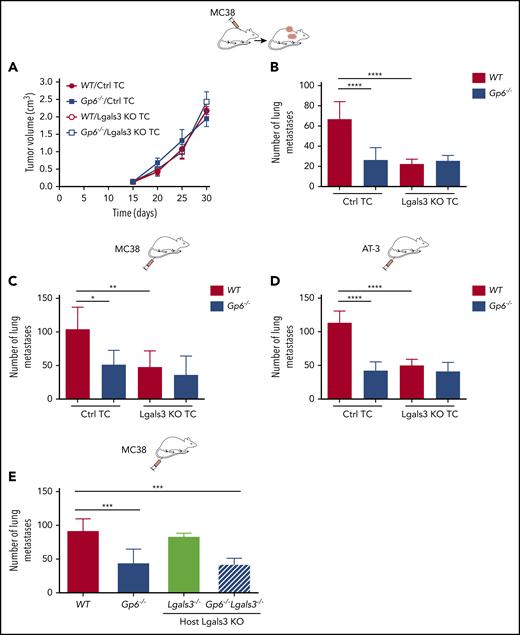

GPVI–galectin-3 interaction regulates lung metastasis

To address the functional consequences of GPVI–galectin-3 interaction for tumor metastasis, MC38 control or galectin-3–deficient cells were injected subcutaneously into WT and Gp6−/− mice. After 30 days, volumes of primary tumors were similar between groups, indicating that neither platelet GPVI nor tumor cell–resident galectin-3 is critical for primary tumor growth (Figure 4A). In contrast, in WT mice, spontaneous metastasis of galectin-3–deficient MC38 cells was decreased by 2.5-fold, compared with that of control cells (Figure 4B). Genetic ablation of galectin-3 in MC38 (Figure 4C) and AT-3 (Figure 4D) cancer cells caused a similar impairment of lung colonization after inoculation via the tail vein. Interestingly, the combined deficiency of GPVI and galectin-3 on platelets and tumor cells, respectively, did not further decrease the number of spontaneous (Figure 4B) or experimental (Figure 4C-D) lung metastases. Galectin-3 is also expressed by stromal, endothelial, and immune cells.59,60 To test whether other galectin-3+ cells may account for the observed phenotype, galectin-3–deficient mice (Lgals3−/−) or Gp6−/−Lgals3−/− double-knockout mice were injected with tumor cells, and lung colonization was assessed after 15 days (Figure 4E). Galectin-3 deficiency in host cells did not affect metastasis, compared with that of the control cells (Figure 4E). Altogether, these results indicate that GPVI–galectin-3 interactions regulate tumor metastasis, but not primary tumor growth.

Galectin-3 on tumor cells mediates lung metastasis through platelet GPVI. Control (Ctrl) and galectin-3–deficient (Lgasl3 KO), MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously (A) or directly into the tail vein (C-E) of WT, Gp6−/− (B-E) and Lgals3−/− or Gp6−/−Lgals3−/− (E) mice. Spontaneous (B) and experimental (C-E) lung metastasis were determined 30 or 15 days after injection, respectively. Quantification of primary MC38 tumor volume (A) and metastases (B-E) in lungs of WT, Gp6−/− (B-E) and Lgals3−/− or Gp6−/−Lgals3−/− (E) mice. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 6 (A-C) and 5 (D-E) mice per group. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, by 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. TC, tumor cells.

Galectin-3 on tumor cells mediates lung metastasis through platelet GPVI. Control (Ctrl) and galectin-3–deficient (Lgasl3 KO), MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously (A) or directly into the tail vein (C-E) of WT, Gp6−/− (B-E) and Lgals3−/− or Gp6−/−Lgals3−/− (E) mice. Spontaneous (B) and experimental (C-E) lung metastasis were determined 30 or 15 days after injection, respectively. Quantification of primary MC38 tumor volume (A) and metastases (B-E) in lungs of WT, Gp6−/− (B-E) and Lgals3−/− or Gp6−/−Lgals3−/− (E) mice. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 6 (A-C) and 5 (D-E) mice per group. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, by 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. TC, tumor cells.

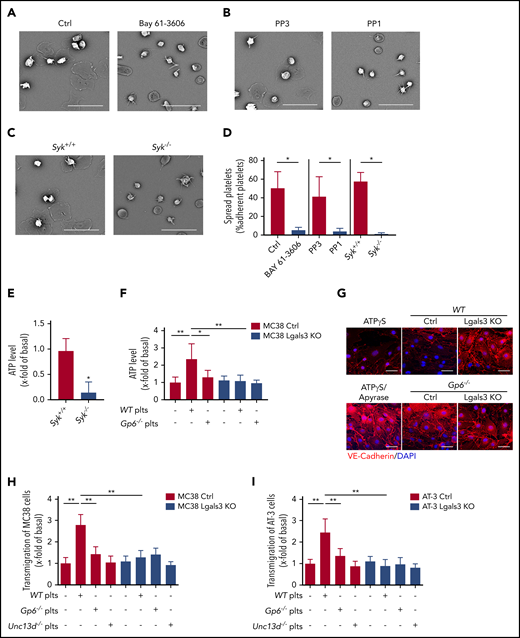

GPVI–galectin-3 interaction promotes tumor cell–induced platelet activation, degranulation, and transendothelial cell migration

Next, we evaluated the role of the GPVI downstream effector Syk and Src kinases in the process of platelet spreading on a galectin-3–coated surface. Whereas control platelets rapidly adhered, formed filopodia, and spread on galectin-3, this process was strongly attenuated in the presence of 10 µM of the Syk inhibitor Bay 61-3606 (Figure 5A,D) or the Src inhibitor PP1 (Figure 5B,D). Syk-deficient platelets also showed similar spreading defects on galectin-3 (Figure 5C-D). This was further confirmed by the reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release of galectin-3–adherent Syk−/− platelets compared with Syk+/+ platelets (Figure 5E). We also found that calcium (Ca2+) signaling, P-selectin exposure (supplemental Figures 7 and 8), and ATP release from Gp6−/− platelets were reduced compared with WT platelets when coincubated with tumor cells (Figure 5F) and that the levels of released ATP were dependent on galectin-3 expression by tumor cells (Figure 5F).

Interaction between GPVI and galectin-3 promotes tumor cell–induced platelet activation, degranulation, and transendothelial migration. (A-C) Representative SEM images of mouse platelets adhering to recombinant galectin-3. Washed WT mouse platelets were incubated for 10 minutes with 10 µmol/L of the Syk inhibitor Bay 61-3606 (A) and Src-kinase inhibitor PP1 and its nonfunctional analog PP3 (B) and was allowed to adhere to galectin-3–coated surfaces. (C) Similar experiments were performed with Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mouse platelets. The morphology of the adhering platelets was examined after 1 hour, and (D) the percentage of spread platelets was quantified for each condition. The bar represents 20 µm. Mean ± standard deviation (SD) of n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (E) Relative levels of ATP released from platelets (Syk+/+ and Syk−/−) adhering to dalectin-3. Mean ± SD; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (F) Relative levels of ATP released from WT and Gp6−/− platelets incubated with control MC38 (Ctrl) or Lgals3 KO tumor cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 4 separate experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, by 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (G) bEnd.3 mouse endothelial cells (ECs) incubated with supernatants derived from platelets (Plts) tumor cell (TC) cocultures (WT Plts+MC38 ctrl or Lgals3 KO TC) and (Gp6−/− Plts+MC38 Ctrl or Lgals3 KO TC), or with 10 µM ATPγS, alone or in combination with 20 U/mL apyrase, for 8 hours. Representative immunofluorescence images of ECs with an anti-VE-cadherin antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 10 µm. (H-I) MC38 and AT-3 ctrl or Lgals3 KO tumor cells were seeded on endothelial cells (ECs), and tumor cell transmigration was determined in the absence or presence of WT, Gp6−/−, and Unc13d−/− plts. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 6 separate experiments. **P < .01, by Mann-Whitney test.

Interaction between GPVI and galectin-3 promotes tumor cell–induced platelet activation, degranulation, and transendothelial migration. (A-C) Representative SEM images of mouse platelets adhering to recombinant galectin-3. Washed WT mouse platelets were incubated for 10 minutes with 10 µmol/L of the Syk inhibitor Bay 61-3606 (A) and Src-kinase inhibitor PP1 and its nonfunctional analog PP3 (B) and was allowed to adhere to galectin-3–coated surfaces. (C) Similar experiments were performed with Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mouse platelets. The morphology of the adhering platelets was examined after 1 hour, and (D) the percentage of spread platelets was quantified for each condition. The bar represents 20 µm. Mean ± standard deviation (SD) of n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (E) Relative levels of ATP released from platelets (Syk+/+ and Syk−/−) adhering to dalectin-3. Mean ± SD; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (F) Relative levels of ATP released from WT and Gp6−/− platelets incubated with control MC38 (Ctrl) or Lgals3 KO tumor cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 4 separate experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, by 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (G) bEnd.3 mouse endothelial cells (ECs) incubated with supernatants derived from platelets (Plts) tumor cell (TC) cocultures (WT Plts+MC38 ctrl or Lgals3 KO TC) and (Gp6−/− Plts+MC38 Ctrl or Lgals3 KO TC), or with 10 µM ATPγS, alone or in combination with 20 U/mL apyrase, for 8 hours. Representative immunofluorescence images of ECs with an anti-VE-cadherin antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 10 µm. (H-I) MC38 and AT-3 ctrl or Lgals3 KO tumor cells were seeded on endothelial cells (ECs), and tumor cell transmigration was determined in the absence or presence of WT, Gp6−/−, and Unc13d−/− plts. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 6 separate experiments. **P < .01, by Mann-Whitney test.

It has been shown that tumor cell–induced platelet degranulation and ATP release stimulate transendothelial migration of tumor cells, thereby enhancing their metastatic potential.3,9,17 Therefore, we hypothesized that GPVI–galectin-3 interactions regulate the transendothelial migration of tumor cells, which requires both endothelial cell tight junction (TJ) disruption and tumor cell migration. To test this directly, WT or GPVI-deficient platelets were incubated with control or galectin-3 knockout tumor cells, and cell-free supernatants were used to treat bEnd.3 endothelial cells. The function of TJs on the cell surface was evaluated with immunofluorescence staining of vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, as previously described.61 Interestingly, VE-cadherin staining was diffuse, and gaps between the cells were apparent, indicative of vascular permeability, when endothelial cells were treated with supernatants derived from cocultures of WT platelets with MC38 cells. In contrast, normal TJs were observed in cells treated with supernatants from Gp6−/− platelets and control MC38 cells or WT platelets incubated with galectin-3–deficient MC38 tumor cells (Figure 5G; supplemental Figure 9). Of note, incubation of endothelial cells with the ATP analog, ATPγS, was sufficient to induce the dissociation of TJs, whereas the addition of the ATP-hydrolyzing enzyme apyrase abolished this process (Figure 5H; supplemental Figure 9). Next, control and galectin-3–knockout tumor cells were allowed to migrate through bEnd.3 mouse endothelial cell–coated transwells, alone or in the presence of washed WT or Gp6−/− platelets. We found that the addition of WT platelets enhanced transendothelial migration of MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells by 2.7- and 2.5-fold, compared with controls without platelets (Figure 5H-I). In contrast, both Gp6−/− platelets incubated with control tumor cells or WT platelets with galectin-3–knockout tumor cells failed to enhance transendothelial migration (Figure 5H-I). Similar results were obtained with platelets isolated from Munc13-4 mice (Unc13d−/−),41 which do not release the major ATP store from their platelet-dense granules (Figure 5H-I). Altogether, these results suggest that GPVI–galectin-3 interactions promote transendothelial migration of tumor cells in vitro and that ATP release from platelet-dense granules stimulate this process.

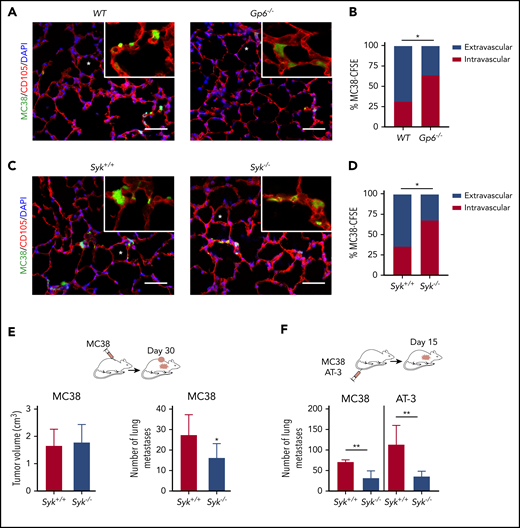

GPVI–galectin-3 interaction promotes tumor cell extravasation and metastasis

To explore whether GPVI and its downstream signaling also have an impact on tumor cell transmigration in vivo, Gp6−/− and WT mice received CFSE-labeled tumor cells IV and were then analyzed at different time points. The number of tumor cells present in the lungs was comparable between the 2 groups 6 hours after injection, but a smaller proportion of cells was localized in the extravascular compartment in Gp6−/− mice compared with the controls (Figure 6A-B). We also found that Syk−/− platelets failed to enhance tumor cell extravasation (Figure 6C-D). Consistently, spontaneous (Figure 6E) and experimental (Figure 6F) metastasis of MC38 colon (Figure 6E-F) and AT-3 breast (Figure 6F) cancer cells were decreased in mice with Syk-deficient platelets, suggesting that ITAM-dependent platelet activation triggered by GPVI–galectin-3 interaction is essential for tumor metastasis.

GPVI–galectin-3 interaction promotes tumor cell extravasation and subsequent metastasis. (A,C) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of lung sections of WT, Gp6−/− (A) and Syk+/+ and Syk−/− (C) mice 6 hours after IV injection of MC38-CFSE cells (green). Lung vessels were stained for endoglin (CD105, red). Asterisks indicate lung alveoli. The bar represents 10 µm. (B-D) The bar graphs show the percentage of intravascular and extravascular MC38-CFSE cells in lungs of WT, Gp6−/−, Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mice; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Fisher’s exact test. (E-F) MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously (E) or directly into the tail vein (F) of Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mice. Spontaneous and experimental lung metastasis were determined at 30 and 15 days after injection, respectively. (E) Quantification showing primary tumor volume (left) and number of metastases (right). (F) Metastases in lungs of Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mice. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 5 mice per group; *P < .05; **P < .01, by Mann-Whitney test.

GPVI–galectin-3 interaction promotes tumor cell extravasation and subsequent metastasis. (A,C) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of lung sections of WT, Gp6−/− (A) and Syk+/+ and Syk−/− (C) mice 6 hours after IV injection of MC38-CFSE cells (green). Lung vessels were stained for endoglin (CD105, red). Asterisks indicate lung alveoli. The bar represents 10 µm. (B-D) The bar graphs show the percentage of intravascular and extravascular MC38-CFSE cells in lungs of WT, Gp6−/−, Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mice; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Fisher’s exact test. (E-F) MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously (E) or directly into the tail vein (F) of Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mice. Spontaneous and experimental lung metastasis were determined at 30 and 15 days after injection, respectively. (E) Quantification showing primary tumor volume (left) and number of metastases (right). (F) Metastases in lungs of Syk+/+ and Syk−/− mice. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 5 mice per group; *P < .05; **P < .01, by Mann-Whitney test.

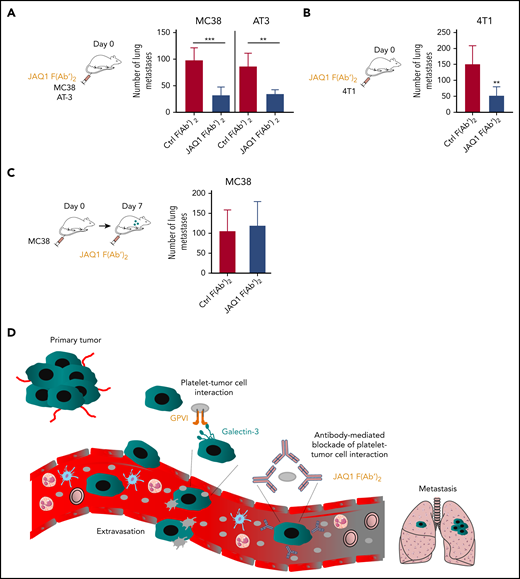

Pharmacological blockade of GPVI reduces tumor metastasis

To address the antimetastatic effects of pharmacologically targeting GPVI, C57BL/6 mice were treated with the GPVI-blocking JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or with an irrelevant IgG F(abʹ)2 control. This GPVI blockade efficiently inhibited lung metastasis of both MC38 colon and AT-3 breast cancer cell lines (Figure 7A). Similar results were obtained with the 4T1 breast cancer cell lung metastasis model in syngeneic BALB/c1 mice (Figure 7B). Of note, JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 treatment did not exert any protective effect on tumor metastasis when given at day 7 after injection of the tumor cells (Figure 7C), suggesting that GPVI plays a role in the earlier steps of tumor metastasis.

Pharmacological blockade of GPVI inhibits tumor metastasis. (A-B) C57BL/6 or BALB/c1 WT mice were injected IV with JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody, together with the indicated syngeneic tumor cells. (A) MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells are syngenic to a C57BL/6 background and 4T1 tumor cells to a BALB/c1 (B) background, respectively. (C) C57BL/6 mice were injected with MC38 tumor cells, followed after 7 days by injection with JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. Number of experimental lung metastases (A,C) in MC38-, AT-3 (A)-, or 4T1 (B)-injected WT mice was determined 15 days after injection. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 5 (A-C) and n = 6 (B) mice per group. **P < .01; ***P < .001, by unpaired Student t test. (D) Proposed model of the role of platelet GPVI in tumor metastasis. Tumor cells transit from the primary tumor via the blood to form metastases in distant organs. During this process, tumor cells encounter several environmental changes and stimuli, which profoundly impact their metastatic potential. Following entry of tumor cells into the bloodstream, platelet GPVI favors platelet recruitment to circulating tumor cells through its interaction with galectin-3 on the tumor cell surface. Once a stable interaction is established, platelets become activated and can protect tumor cells from hemodynamic shear stress and the host immune system and can favor efficient tumor cell extravasation and subsequent metastasis. The function-blocking anti-GPVI antibody JAQ1 F(Ab’)2 reduces metastasis by preventing platelet–tumor cell cross talk.

Pharmacological blockade of GPVI inhibits tumor metastasis. (A-B) C57BL/6 or BALB/c1 WT mice were injected IV with JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody, together with the indicated syngeneic tumor cells. (A) MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells are syngenic to a C57BL/6 background and 4T1 tumor cells to a BALB/c1 (B) background, respectively. (C) C57BL/6 mice were injected with MC38 tumor cells, followed after 7 days by injection with JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. Number of experimental lung metastases (A,C) in MC38-, AT-3 (A)-, or 4T1 (B)-injected WT mice was determined 15 days after injection. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 5 (A-C) and n = 6 (B) mice per group. **P < .01; ***P < .001, by unpaired Student t test. (D) Proposed model of the role of platelet GPVI in tumor metastasis. Tumor cells transit from the primary tumor via the blood to form metastases in distant organs. During this process, tumor cells encounter several environmental changes and stimuli, which profoundly impact their metastatic potential. Following entry of tumor cells into the bloodstream, platelet GPVI favors platelet recruitment to circulating tumor cells through its interaction with galectin-3 on the tumor cell surface. Once a stable interaction is established, platelets become activated and can protect tumor cells from hemodynamic shear stress and the host immune system and can favor efficient tumor cell extravasation and subsequent metastasis. The function-blocking anti-GPVI antibody JAQ1 F(Ab’)2 reduces metastasis by preventing platelet–tumor cell cross talk.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated a key role of GPVI in supporting platelet adhesion to tumor cells and identified galectin-3 as a major GPVI ligand on tumor cells that induces platelet activation to promote colon and breast cancer metastasis.

Galectin-3 is mainly located in the cytoplasm, but is also found in the nucleus and on the cell surface and is also secreted into the circulating blood.59,62 In addition, galectin-3 has been detected on the surface of different cancer cell types and is also associated with mucins, glycans, and integrins.62-67 Galectin-3 bears a unique putative collagen-like domain, whereas the other galectin isoforms lack this structure.52,62,68 To visualize the putative binding sites of galectin-3 on the protein surface of GPVI, bioinformatics tools and crystal structures of galectin-3 and GPVI were used. By using a free-energy calculation method,69 we found that the binding affinity of GPVI to galectin-3 seems to be close to type I or III collagen. Using different experimental settings, we demonstrated that tumor-resident galectin-3 is a binding partner of platelet GPVI and that this interaction induces platelet activation, shape change, degranulation, and ATP secretion. Platelet-released ATP has been shown to act on the endothelial purinergic receptor P2Y2, thereby increasing vascular permeability, which further enhances tumor cell extravasation.9 In line with this report, our findings suggest that galectin-3–GPVI–mediated platelet ATP release promotes tumor cell extravasation by inducing vascular permeability, thus strongly facilitating metastasis formation in distant organs (Figure 7D).

It has been shown that downregulation of galectin-3 in osteosarcoma, thyroid, and gastric cancer cells leads to decreased tumor cell invasion and metastasis.70-72 In agreement with these studies, our results also suggest a prometastatic function of colon and breast cancer cell–derived galectin-3 in our immunocompetent mouse models. Jain and collaborators38 described that GPVI deficiency in mice results in decreased experimental metastasis of B16F10 melanoma and LLC cells. Interestingly, galectin-3 is detectable in both types of cancer cells,73 and LLC tumor cells interact with platelets through GPVI.

Galectin-3 in human melanoma cell xenografts and experimental B16F10 melanoma models increases cell motility and tumor metastasis.73-75 However, in sharp contrast, Hayashi et al76 proposed a metastasis-suppressing function of galectin-3, based on the observation that low expression of galectin-3 is associated with high expression of β3 integrin on the surface of B16F10 cells, and enhances their metastatic potential by facilitating the interaction with fibrinogen and platelets. On the other hand, in that study, the overexpression of galectin-3 resulted in the downregulation of β3 integrin and consequently reduced the metastatic potential of the cells.76 Contrary to those results, we found that expression levels of galectin-3 had no influence on the expression of β3 integrin in our cancer cells, demonstrating that the mechanism reported for B16F10 cells is not of general relevance (supplemental Figure 10). Furthermore, we used several cancer cell types, covering a spectrum of differentiation and metastatic propensities77-83 and clearly showed that inhibition of platelet GPVI or tumor cell–derived galectin-3 decreased platelet–tumor cell interaction and metastasis. Our findings also strongly support the clinical observations in humans that increased galectin-3 levels in solid tumors, including melanoma, colon, and breast carcinoma, correlate with a poor prognosis and shortened survival and are associated with an increased number of metastases in the lung and liver.63,84-87 A possible pathogenic role of GPVI–galectin-3 interaction in human cancer remains to be demonstrated, but we clearly showed that human cancer cells also interact with human platelets through GPVI. Furthermore, in preliminary studies, we found increased levels of soluble GPVI, indicative of intravascular GPVI–ITAM activation, in the plasma of patients with advanced stages of colorectal and breast cancers (supplemental Tables 2 and 4), which correlated positively with cancer stage in these small cohorts (supplemental Figure 11). Whether GPVI shedding from the platelet surface was induced by galectin-3 or other ligands in these patients remains to be addressed in future studies.

Previously, it has been shown that, under inflammatory conditions, GPVI may also enhance vascular permeability by mediating adhesion of platelets to the inflamed microvasculature.88,89 In contrast, we found that GPVI deficiency did not alter platelet–endothelial cell interactions in our cancer model (supplemental Figure 12), suggesting that enhanced vascular permeability during tumor metastasis is a consequence of GPVI-mediated degranulation in response to galectin-3.

Platelets are the first cells to interact with tumor cells in the bloodstream, which is followed by the progressive recruitment of neutrophils to generate a metastatic niche.6,90-92 Recently, we showed that inhibition of GPVI function could induce intratumoral hemorrhages, observed in the neutrophil-rich area of the primary tumor.39 Interestingly, galectin-3 deficiency, neither in tumor cells nor in tumor microenvironment, resulted in intratumoral hemorrhages, and GPVI deficiency did not induce hemorrhages in secondary tumors or metastases (supplemental Figure 13). However, neutrophil depletion in WT mice reduced tumor metastasis, which was further reduced in GPVI-deficient mice (supplemental Figure 14), suggesting that the metastasis-enhancing effect of neutrophils is not dependent on GPVI function. Although galectin-3 is expressed in neutrophils, galectin-3 deficiency in host cells (Lgals3−/− mice) did not influence metastasis of MC38 and AT-3 tumor cells.

GPVI is exclusively expressed in the megacaryocyte/platelet lineage, largely excluding the risk of side effects of GPVI-blocking agents on other cell types. Consistently, the injection of JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 antibody into Gp6−/− mice did not induce any further decrease in tumor metastasis, confirming the specificity of the anti-GPVI treatment (supplemental Figure 15). Furthermore, we provide the first in vivo evidence that GPVI blockade prevents platelet/tumor cell interactions and inhibits lung metastasis in mice. This opens a new perspective to develop a therapeutic strategy aiming to target GPVI, thereby inhibiting tumor metastasis in cancer patients. In line with previous reports, JAQ1 injection did not induce severe thrombocytopenia, and the resultant GPVI deficiency had no major effect on normal hemostasis.32,93 Similarly, GPVI deficiency in humans causes a relatively mild bleeding diathesis94 ; therefore, it is tempting to speculate that targeting of GPVI in patients should be possible without inducing major bleeding complications.

A randomized cardiovascular prevention trial has provided evidence of an antimetastatic effect of low, platelet-inhibiting doses of ASA in patients.95 In our AT-3 cancer model, ASA alone strongly inhibited tumor metastasis, which was further decreased by using combined therapy with ASA and JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 (supplemental Figure 16). Consistently, Lucotti et al96 recently showed that ASA treatment could decrease platelet aggregation on tumor cells, endothelial cell activation, tumor cell–endothelial cell interactions, and recruitment of metastasis-promoting monocytes to premetastatic niches. Although our results show that GPVI blockade inhibits the early phase of cancer metastasis (ie, the time frame in which platelet–tumor cell interactions occur6 ), ASA treatment seemed to act on both early and late phases of metastasis. Whether such dual therapy could be applied to cancer patients will require further investigation. However, a major drawback of ASA and other currently used antiplatelet drugs is their strong effects on hemostasis,4,95,97-100 which limits their use in clinical settings. Of note, it has been shown that anti-GPVI therapy may result in markedly prolonged bleeding times when given in combination with ASA.101

Revacept, a competitive GPVI inhibitor comprising the GPVI ectodomain fused to human IgG Fc, has been successfully evaluated in clinical trial phase I.102-104 Previously, Dovizio et al105 showed that Revacept has inhibitory effects on platelet-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition and cyclooxygenase-2 synthesis in vitro in HT29 cells. We evaluated the antimetastatic potential of a soluble dimeric mouse GPVI-Fc fusion protein,43 an agent similar to Revacept. Soluble GPVI-Fc dimer treatment decreased platelet–tumor cell interactions and metastasis of MC38 and AT-3 cells to a similar extent as JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 treatment, but we did not find any changes in the expression profile of epithelial and mesenchymal gene markers, upon treatment with either GPVI-Fc or JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 (supplemental Figure 17).

To summarize, our study demonstrates a major contribution of GPVI to platelet interaction with colon and breast cancer cells through the binding of galectin-3. This interaction triggers platelet activation and subsequent extravasation of tumor cells. Therefore, targeting of GPVI in humans may represent a novel antimetastatic strategy without significantly affecting hemostasis.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Steve Watson (University of Birmingham, United Kingdom) for scientific discussion, Pedro Berraondo Lopez (University of Navarra, Spain) for MC38 cells, and Alexander Deuschel and Daniela Naumann (University of Würzburg, Rudolf Virchow Center, Würzburg, Germany) for technical assistance.

E.M.-B. was supported by the European Union (Europäischer Fonds für regionale Entwicklung [EFFRE])-Bayern. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft ([DFG] German Research Foundation) grant 374031971-TRR 240.

Authorship

Contribution: E.M.-B. designed the research, acquired and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; J.G.-P., E.S., P.B., S.S., C.S., and A.B. acquired and analyzed the data; K.R., T.D., D.M., P.N., A.T.N., and S.I.A. interpreted the data; D.S., T.D., L.N., M.D., D.M., and S.I.A. provided essential tools; and B.N. designed the research, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and acquired the funding.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.B. is Walther-Straub Institute for Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ludwig-Maximillian’s University, German Center for Lung Research, Munich, Germany.

Correspondence: Bernhard Nieswandt, Institute of Experimental Biomedicine, University Hospital and Rudolf Virchow Center, University of Würzburg, Josef-Schneider-Straße 2, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; e-mail: bernhard.nieswandt@virchow.uni-wuerzburg.de.

![Galectin-3 expressed on tumor cells supports GPVI-dependent platelet adhesion. (A) Prediction of binding affinity between galectin-3 (red) and GPVI (blue). Graphs correspond to ΔGbind = −5.91 kcal/mol and KD = 44.89 μM, respectively. Potential of mean force (PMF) values were extracted by the weighted histogram analysis method, which yields the binding free energy (ΔGbind) for the binding and unbinding processes. The ΔGbind value was calculated as the difference between the highest and lowest values of the PMF curve. The KD of the protein–protein complex was calculated from the ΔGbind value according to the following equation: KD = exp(ΔGbind/R · T), where R (gas constant) is 1.98 cal(mol·K)−1 and T (room temperature) is 298.15 Kelvins (K). The Boltzmann (sigmoidal) nonlinear fitting [R2 = 0.85; RMSE (root mean square error) = 0.67; RSS (residual sum of squares) = 88.31] of the data set is shown to assess the PMF elevation pattern with the increase of reaction coordinate (ξ), using the scaled Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm with tolerance = 0.0001. (B-C) Knockout of the galectin-3 gene (Lgals3 KO) expression in MC38 and AT-3 cells. (B) Galectin-3 mRNA expression was determined by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and normalized with a messenger RNA level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 4 separate cell culture experiments; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of galectin-3 (Lgals3 KO) knockout MC38 and AT-3 cells or cells expressing galectin-3 gene (Ctrl: control), with an anti-galectin-3 antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). The bar represents 20 µm. (D-E) Quantification of the fluorescence signal corresponding to the amount of WT (D-E) and Gp6−/− (D) mouse platelets adhering to (D-E) MC38 and AT-3 Ctrl and Lgals3 KO cancer cells. (D) Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group. MC38 Ctrl/WT platelets (plts; 3.607 ± 0.6198); MC38 Ctrl/Gp6−/− plts (1.593 ± 0.2774); MC38 Lgals3 KO/WT plts (1.6 ± 0.2402); and MC38 Lgals3 KO/Gp6−/− plts (1.423 ± 0.1665). AT-3 Ctrl/WT plts (5.37 ± 0.3005); AT-3 Ctrl/Gp6−/− plts (1.897 ± 0.4944); AT-3 Lgals3 KO/WT plts (1.817 ± 0.586); and AT-3 Lgals3 KO/Gp6−/− plts (1.683 ± 0.486). ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (E) Similar experiments were performed with WT platelets in the absence or presence of JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 or an irrelevant control F(abʹ)2 antibody. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group. MC38 Ctrl/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (5.017 ± 0.2055); MC38 Ctrl/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.437 ± 0.493); MC38 Lgals3 KO/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (2.757 ± 0.2139); and MC38 Lgals3 KO/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.273 ± 0.4366). AT-3 Ctrl/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (5.313 ± 0.5326); AT-3 Ctrl/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.38 ± 1.057); AT-3 Lgals3 KO/Ctrl F(abʹ)2 plts (1.967 ± 0.2259); and AT-3 Lgals3 KO/JAQ1 F(abʹ)2 plts (2.01 ± 0.1825). **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (F,H) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of mouse (WT and Gp6−/−) (F) and human (H; top; Ctrl, healthy subject; hGP6+/−, human patient with heterozygous mutation; and hGP6−/−, human patient with homozygous mutation) platelets adhering to recombinant galectin-3 under static conditions. The bar represents 20 µm. (H, bottom). Representative immunofluorescence images of GPVI-Fc–conjugated fluorescent microspheres adhering on galectin-1–, galectin-3– and collagen I–coated surfaces. (G,I) Quantification of adherent mouse (G) and human (I) platelets under static conditions on galectin-3. (G) Mean ± SD; n = 4 mice per group; *P < .05, by Mann-Whitney test. (I) Mean ± SD. Ctrl, n = 5; hGP6+/−, n = 2; and hGP6−/−, n = 3. (J) Binding of dimeric GPVI to galectin-3. GPVI–Fc-Alexa-488 was added to microwells coated with galectin-1, galectin-3, collagen I, or bovine serum albumin (BSA). Protein binding was assessed by measuring the fluorescence intensity (FI) at 488 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 4 separate experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/135/14/10.1182_blood.2019002649/2/m_bloodbld2019002649f3.png?Expires=1770508951&Signature=hX~qiiNhvwmwJ8vVQ1uEC~rn0Rt9OsmAB57z9cmdzmhBRS-JvDJdgp0Yxnkhqdwf3e~9hjUuBZg7xID4VJJsF5-53k6a76due4i0P39WGGSzM0PElv3mg9-vZcdHnSniZqZ-NIW-OiPcnobf8SpvdlEVBPSreJRYycK45sgUaSM26Crqxhk7t3Q2-3gE7-srcRL3FdWi0ed3MqhBnbJfmtoIxzc5jtUcO1ZfVHZPRgut4QF8BPfbC9jgs7NuOKyVWMictb7yAMAcKaB9Nf0D0u6T8CapjO-uEDAcsZ6nLnGhOYtDzoeRxab6JA5eEppp~FrFSsT24hKdjAfsKyiycw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)