Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare syndrome that can present with variable clinical and laboratory manifestations, and some distinct features are seen in adults. Type B lactic acidosis, which occurs in the absence of tissue hypoxia, has been reported in a few adult patients with HLH. We report a case of HLH presenting with type B lactic acidosis, with a literature review of this association.

A 48-year-old Saudi woman with a past medical history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and morbid obesity, presented with a 1-month history of intermittent high-grade fever up to 39°C daily. The patient was admitted for further evaluation of fever and was in our hospital for 70 days. Initial laboratory investigations revealed normocytic hypochromic anemia (102 g/L [normal 120-160]), lactic acidosis (2.36 mmol/L [0.5-2.2]), mild transaminitis, and elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase (1761 U/L [125-220]), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (95 mm/hr [0-20]), and ferritin (1090.5 μg/L [4.6-204.0]). Further investigations failed to reveal any autoimmune or rheumatologic disease and extensive septic workup was negative. Lymphocyte subset by flow cytometry showed a low percentage of absolute natural killer cells (5% [10-20%]). Abdominal CT revealed splenomegaly with a span of 16.5 cm. Positron emission tomography-CT scan showed diffuse prominence of splenic activity, with a standardized uptake value of 4.5, and bone marrow activity throughout the axial skeleton. Liver biopsy and bone marrow aspiration were unremarkable.

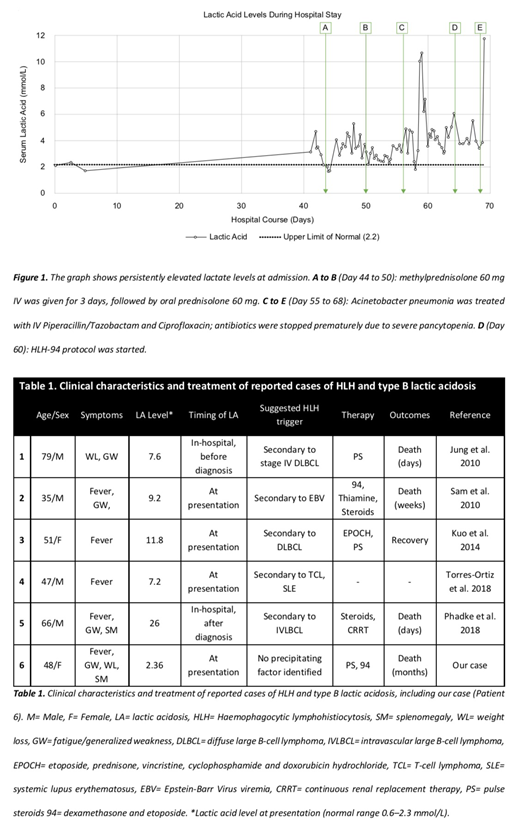

A month after admission, her anemia worsened with the hemoglobin level gradually dropping to 63 g/L prompting multiple transfusions. Lactic acid levels remained persistently elevated throughout this period [Figure 1]. A trial of intravenous steroids and immunoglobulins failed to decrease the lactic acid level [Figure 1; A to B]. The hospital course was complicated by Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia requiring antibiotics [Figure 1; C to E].

Two months after the initial presentation, she developed pancytopenia, and repeated bone marrow aspiration and biopsy showed hemophagocytosis. Repeated ferritin level was more than 40,000 μg/L with hypertriglyceridemia (2.92 mmol/L [<1.7]), and hypofibrinogenemia (0.9 g/L [1.5-4.1]). HLH-94 protocol with etoposide (150 mg/m2twice weekly) and dexamethasone (10 mg/m2) was commenced; however, the patient continued to deteriorate prompting elective intubation. She then developed acute acalculous cholecystitis and brain CT revealed a large central pontine hypodensity. Nine days after initiation, the patient was switched from the HLH-94 protocol to alemtuzumab, however, the patient arrested and passed away.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of HLH presenting with persistent lactic acidosis lasting several weeks. Although no cause was found, this patient likely had HLH that was not detected early.

We searched the PubMed and EMBASE databases for English-language reports describing adult patients (>18 years) with HLH and lactic acidosis. Patients with type A lactic acidosis, associated with tissue hypoxia, were excluded.

Five case reports describing patients with variable underlying diagnosis causing HLH and type B lactic acidosis were identified (Table I). Lactic acidosis started before HLH was diagnosed in all patients except one, in whom lactic acidosis developed two days after diagnosis. All patients had neither sepsis nor hypotension at the time of lactic acidosis.

The mechanism of type B lactic acidosis in HLH is poorly understood and is likely multifactorial. As HLH in adults is more likely to be secondary to malignancies, Warburg effect, a high rate of glycolysis exhibited by tumor cells, has been proposed as the cause in these cases. Alternatively, acute cytokine hyperactivation in inflammatory states can enhance lactate dehydrogenase activity leading to excess lactic acid production. Inflammation, infection, or tumor cells can also induce stress and accelerate aerobic glycolysis-which does not depend on hypoxia-resulting in excess lactate production. Finally, acute hepatic dysfunction, a common finding in adult-onset HLH, can impair lactate clearance and further elevate levels.

This report suggests that type B lactic acidosis may be a manifestation of HLH. Analyses of large HLH registries can better clarify the diagnostic and prognostic value of type B lactic acidosis in adult-onset HLH.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal