Introduction: The classical BCR-ABL1 negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal disorders of marrow overproliferation. Clinical phenotypes include polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocytosis (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF). In adults, both risk stratifications and treatment guidelines are available to physicians. Various agents, including clinical trial agents, are utilized for treatment in adults. Conversely, there are no management guidelines for children with MPNs, and therapeutic options are limited. Hydroxyurea (HU) is the most commonly used agent in children, likely because of physician experience using this medication for sickle cell anemia. Children with MPN have been treated with HU with effective cytoreduction, although its use is controversial because of the concern for leukemogenicity. While it is still considered as first-line therapy in adults with MPNs, some guidelines recommend avoiding hydroxyurea in younger adult patients. Interferon (IFN) has been utilized in adults with MPNs for many years, and pegylated forms (PEG) have made the medication more tolerable. Enthusiasm in IFN is increasing, due to reports in adult patients of hematologic remissions and significant molecular responses, including molecular remissions in rare cases. Given its improved tolerability and potential benefits, IFN may be an appropriate choice for treatment in many children with MPNs. Given the limited experience in this population and available literature, we sought to review a small cohort of pediatric MPNs treated with PEG.

Methods: We reviewed the charts of pediatric patients with MPNs who have been treated with PEG and pooled de-identified data. Demographic, mutational, laboratory, and treatment-specific information was documented. This study was approved by institutional IRBs.

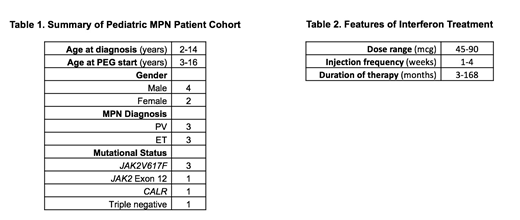

Results: Six children were identified at four institutions who had been treated with IFN (Table 1). Age at diagnosis of MPN ranged from 2-14 years, and age at onset of PEG therapy ranged from 3-16 years. Two children are female, and four are male. Three children were diagnosed with PV and three with ET. One child with PV is positive for a JAK2 Exon 12 mutation, three children have JAK2V617F mutations (two with PV and one with ET), one child with ET has a CALR mutation, and one child has triple-negative ET.

Cytoreductive therapy was started in this cohort for a variety of reasons, including worsening counts, concerning marrow findings, and symptoms (headache being the most common.) Three of the children in this cohort had been treated with HU prior to starting PEG. Reasons for switching cytoreduction to PEG included family concern for increased risk of malignancy and concern for negative effects on future fertility, interest in a disease-modifying agent, and poor side-effect profile of HU.

PEG doses ranged from 45 to 90 mcg per dose (Table 2), with dosing frequency ranging from one dose every 1-4 weeks. Blood counts remained generally stable or improved in this cohort; no children required stopping and switching to another cytoreductive agent. One subject developed a pulmonary embolism while on PEG, but was able to remain on therapy; no other MPN-related complications occurred while on PEG. Some children experienced improvement in clinical disease-related symptoms. Mild side-effects reported by subjects included headache, flu-like symptoms, injection site reaction, and abdominal pain. One child had PEG dosed less frequently because of issues with depression and anxiety, and ultimately had therapy discontinued due to normalization of platelet counts. No other dose-limiting drug-related toxicity was reported. All other subjects remain on therapy with PEG, and the duration of therapy ranges from 3-168 months.

Conclusion: This cohort of young MPN patients has been treated with PEG with no major dose-limiting toxicity, and with sustained tolerability. While further study is needed, it is clear that PEG can have a role to play in the management of children with MPNs. Having multiple options for cytoreduction available for families to discuss with their pediatric practitioners allows for greater family autonomy. Our results to date highlight the need for prospective study of a larger group of young patients with MPNs treated with PEG.

Bergmann:Novartis: Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; Genentech: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Octapharma: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Pfizer: Research Funding; Shire/Takeda: Research Funding; NovoNordisk: Research Funding. Mascarenhas:Pharmaessentia: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Merus: Research Funding; Promedior: Research Funding; Janssen: Research Funding; Incyte: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Novartis: Research Funding; Roche: Consultancy, Research Funding; Merck: Research Funding; Celgene: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; CTI Biopharma: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding. Verstovsek:Gilead: Research Funding; Promedior: Research Funding; CTI BioPharma Corp: Research Funding; Genetech: Research Funding; Blueprint Medicines Corp: Research Funding; Novartis: Consultancy, Research Funding; Sierra Oncology: Research Funding; Pharma Essentia: Research Funding; Astrazeneca: Research Funding; Ital Pharma: Research Funding; Protaganist Therapeutics: Research Funding; Constellation: Consultancy; Pragmatist: Consultancy; Incyte: Research Funding; Roche: Research Funding; NS Pharma: Research Funding; Celgene: Consultancy, Research Funding. Hoffman:Merus: Research Funding.

Use of interferon and hydroxyurea in children with MPNs is off-label

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal