Abstract

Venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab is an efficacious and tolerable combination that provides a fixed-duration, chemotherapy-free option for patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). With the expanding number of therapeutic alternatives available for CLL, discussion of efficacy and potential adverse effects is paramount to formulating the optimal treatment regimen for each individual patient. Many ongoing studies will further define the ideal combination and long-term efficacy of these novel therapies in a prospective manner.

Introduction

Frontline treatment options for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients have evolved rapidly. The current trend has directed patients away from standard chemoimmunotherapy agents, such as fludarabine, and toward targeted therapies, such as ibrutinib. The most recent targeted agent approved in the frontline setting is venetoclax, an oral B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor. The rapid evolution of therapeutic options has left treating physicians with the challenge of selecting the optimal initial management for CLL patients. This article will briefly review the data supporting currently approved frontline therapy for CLL, detail data supporting the use of venetoclax in the frontline setting, compare key features of currently available frontline therapies, and explore future applications for venetoclax.

Frontline therapy for patients with CLL

Over the years, multiple landmark phase 3 trials have introduced efficacious therapeutic options for the frontline therapy of patients with CLL.1-3 Regimens containing standard cytotoxic chemotherapy agents (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, bendamustine, and chlorambucil) in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (rituximab and obinutuzumab) were considered the standard of care for many years. The goals of these regimens were to induce the deepest and longest remission possible and allow for CLL-related symptom relief for the longest possible period of time. Achieving the desired state of no detectable minimal residual disease (MRD) denoted significant depth of remission and has been associated with prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).4 Unfortunately, these cytotoxic therapies do not specifically target CLL cells and induce significant toxicity. With the goals of limiting toxicity and improving efficacy, therapies designed to specifically target CLL cells were developed. Ibrutinib, an oral inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase, was the first targeted therapy approved for marketing for the treatment of CLL patients by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Ibrutinib gained full FDA marketing approval for CLL therapy after the RESONATE2 study demonstrated an improved overall response rate (ORR; 86% vs 35%), 2-year PFS (89% vs 34%), and 2-year OS (98% vs 85%) when compared with chlorambucil in patients with previously untreated CLL.5 The efficacy of ibrutinib led to 2 large phase 3 studies comparing ibrutinib (± rituximab) to chemoimmunotherapy regimens in the frontline treatment of older (≥65 years; bendamustine and rituximab [BR]; A041202 trial) or younger (<65 years; fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab [FCR]; E1912 trial) patients with CLL.6,7 Although both studies showed that ibrutinib-treated patients had longer PFS than those treated with chemoimmunotherapy, a notable lack in the ability of ibrutinib to induce complete response (CR) and MRD− remission was observed.6,7 The chemoimmunotherapy regimens resulted in an ∼30% CR rate with 59% and 8% of patients who received FCR and BR, respectively, achieving MRD− remissions.6,7 For patients treated with ibrutinib-containing regimens on these trials, the CR rates were <20%, and <10% of patients achieved MRD negativity in the peripheral blood.6,7 Although extended follow-up of the original RESONATE2 study suggests that remissions deepen over time with continued ibrutinib therapy, it is clear that continuous and indefinite therapy with ibrutinib is required to maintain clinical benefit.8 During the same time frame, alternate targeted therapies for CLL patients were under clinical development, including venetoclax.

Mechanism of venetoclax in CLL

CLL cells overexpress BCL2, an antiapoptotic protein that renders the cells resistant to apoptosis and allows accumulation of long-lived malignant cells.9,10 Therefore, BCL2 blockade is a rational therapeutic strategy in CLL. Venetoclax is an oral BCL2 homology domain 3 (BH3) mimetic that disrupts antiapoptotic signaling via BCL2, thereby inducing CLL cell death.11

Venetoclax therapy in patients with in R/R CLL

Venetoclax formally entered the clinical trials for CLL patients in 2011 when a first-in-human study initially enrolled and treated 3 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL. Early evidence of significant activity was detected when rapid reduction of lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy was demonstrated even after a single dose of venetoclax. Notably, all 3 of the patients had laboratory evidence of tumor lysis.11 A subsequent phase 1 study for 116 patients with heavily pretreated CLL demonstrated an impressive 79% ORR in this high-risk group.12 Notably, 20% of these patients achieved CR, including 5% of patients without detectable MRD, a feature that distinguishes venetoclax from responses seen with single-agent ibrutinib.12 In this early study, clinical development of venetoclax in CLL was nearly thwarted by significant clinical events of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). After introduction of TLS risk-stratification criteria and an extended 5-week stepwise ramp-up of the venetoclax dose with TLS prophylaxis and monitoring, only 1 additional patient had laboratory evidence of TLS and none experienced clinical sequelae.12,13

Subsequently, the phase 3 MURANO study evaluated venetoclax therapy in patients with R/R CLL.14 The study compared the combination of venetoclax (fixed duration, 2 years) and rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody; fixed duration with 6 monthly doses) to bendamustine and rituximab in patients with R/R CLL.14 The study met its primary end point by demonstrating a 2-year PFS rate of 85% in patients who received venetoclax and rituximab as compared with 36% in patients who received bendamustine and rituximab.14 This PFS advantage was maintained across all high-risk groups including patients with del(17p) karyotype and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) status.14 The ORR demonstrated in patients who received venetoclax and rituximab was an impressive 92% with 84% of these patients achieving MRD− status in the peripheral blood during the trial.14 Based on the MURANO study, venetoclax in combination with rituximab was granted full FDA approval for marketing for all patients with R/R CLL on 8 June 2018.

Venetoclax therapy in patients with previously untreated CLL

Due to the significant efficacy and tolerability of venetoclax in patients with R/R CLL, the next rational place to study venetoclax was the frontline setting. Both preclinical and clinical data suggested that combining venetoclax with obinutuzumab (VO; a third-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) could optimize clinical outcomes such as response, attainability of MRD− status, and survival for patients with previously untreated CLL. Obinutuzumab is a type II humanized antibody that promotes direct cytotoxicity and features an afucosylated Fc region that promotes antibody-dependent natural killer (NK)–cell–mediated cytotoxicity.15 In primary CLL cells, obinutuzumab treatment demonstrated superior cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent NK-cell–mediated cytotoxicity when compared with rituximab treatment.15 These preclinical data translated to clinical data in the CLL11 study where CLL patients treated with frontline obinutuzmab and chlorambucil had prolonged PFS, OS, and higher rates of CR compared with patients treated with frontline rituximab and chlorambucil.3,16 Based upon this study, obinutuzumab and chlorambucil earned FDA approval for marketing for frontline therapy of CLL.

In subsequent preclinical study, apoptosis of CLL cells was shown to be significantly higher after VO therapy compared with venetoclax and rituximab combination therapy or venetoclax alone.17 These preclinical data were translated to a phase 1b study where 32 previously untreated CLL patients received combination fixed-duration therapy with 6 months of IV obinutuzumab and 12 months of oral venetoclax (Table 1).17 The patients on this study demonstrated an impressive ORR of 100%, with 91% achieving MRD− status in their peripheral blood after completion of obinutuzumab therapy.17 The regimen was tolerable, with no clinical cases of TLS, and neutropenia as the most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events (AEs) in 47% and 16%, respectively.17 An early report of the phase 2 Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hemato-oncology (HOVON) 139/GIVE trial, in which 30 patients with previously untreated CLL received 2 months of obinutuzumab therapy prior to initiation of venetoclax, demonstrated that 83% were downgraded from their initial TLS risk level (Table 1).18 No patient remained “high risk” after the initial obinutuzumab therapy, which allowed patients to receive TLS monitoring on an outpatient basis. No clinical TLS was seen on this study.18 Eighty-two percent (24 of 29) of the patients achieved MRD− status in the peripheral blood after completion of obinutuzumab therapy.18 These early studies demonstrated safety and significant efficacy for the VO combination in patients with previously untreated CLL.

Combination therapies with venetoclax for patients with treatment-naive CLL

| Regimen . | Phase . | n . | ORR, % . | CRR, % . | MRD− status, % . | Median follow-up, mo . | PFS . | Median DOR . | OS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO17 (NCT01685892) | 1b | 32 | 100 | 78 | 91: 3 mo after last obinutuzumab 91: 9 mo after last obinutuzumab 78: 12 mo after last obinutuzumab | 26.7 | 2 y = 90.6% | NR | NR |

| VO18 | 2 | 30 | NA | NA | 80 (24/29): end of obinutuzumab 86 (24/28): 6 mo after last obinutuzumab 89 (16/18): 9 mo after last obinutuzumab | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VO19 (NCT02242942) | 3 | 216 | 84.7 | 49.5 | 75.5: 3 mo after venetoclax | 28.1 | 2 y = 88.2% | NR | 2 y = 92% |

| Venetoclax + ibrutinib26 (NCT02756897) | 2 | 80 | 100* | 96* | 69: 18 mo of combination* | 14.8 | 1 y = 98% | NR | 1 y = 99% |

| Venetoclax + ibrutinib + obinutuzumab27 (NCT02427451) | 2 | 25 | 84† | 32† | 83: end of obinutuzumab 95: 2 mo after last obinutuzumab | 24.2 | NA | NA | NA |

| Regimen . | Phase . | n . | ORR, % . | CRR, % . | MRD− status, % . | Median follow-up, mo . | PFS . | Median DOR . | OS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO17 (NCT01685892) | 1b | 32 | 100 | 78 | 91: 3 mo after last obinutuzumab 91: 9 mo after last obinutuzumab 78: 12 mo after last obinutuzumab | 26.7 | 2 y = 90.6% | NR | NR |

| VO18 | 2 | 30 | NA | NA | 80 (24/29): end of obinutuzumab 86 (24/28): 6 mo after last obinutuzumab 89 (16/18): 9 mo after last obinutuzumab | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VO19 (NCT02242942) | 3 | 216 | 84.7 | 49.5 | 75.5: 3 mo after venetoclax | 28.1 | 2 y = 88.2% | NR | 2 y = 92% |

| Venetoclax + ibrutinib26 (NCT02756897) | 2 | 80 | 100* | 96* | 69: 18 mo of combination* | 14.8 | 1 y = 98% | NR | 1 y = 99% |

| Venetoclax + ibrutinib + obinutuzumab27 (NCT02427451) | 2 | 25 | 84† | 32† | 83: end of obinutuzumab 95: 2 mo after last obinutuzumab | 24.2 | NA | NA | NA |

CRR, complete response rate; DOR, duration of response; NA, not available; NR, not reached.

Not reported by intention-to-treat population. As assessed in 26 available patients after 18 cycles of ibrutinib and venetoclax combination therapy.

As assessed by intention to treat.

Anticipating safety and efficacy of this promising regimen, the German CLL Study group planned and conducted the international phase 3 CLL14 study (Table 1).19 This study compared VO to chlorambucil and obinutuzumab therapy in treatment-naive CLL patients with comorbid conditions. Included patients had either a Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score of >6 or a creatinine clearance of <70 mL/min. In this study, obinutuzumab was administered IV at doses of 100 mg on cycle 1 day 1 (C1D1), 900 mg on C1D2, and 1000 mg on C1D8, C1D15, and C2-6D1. On the venetoclax combination arm, the daily venetoclax regimen was initiated on C1D22 with the standard 4-week dose ramp-up (1 week each of 20, 50, 100, and 200 mg) to the targeted continuous dose of 400 mg daily. Venetoclax was discontinued at the completion of cycle 12. The study met its primary end point by demonstrating a 2-year PFS rate of 88% in patients who received venetoclax and obinutuzumab as compared with 64% in patients who received chlorambucil and obinutuzumab.19 This PFS benefit was also observed in patients with unmutated IGHV status and those with TP53 mutations and/or deletions. Response and MRD assessments were conducted according to intent-to-treat populations. In patients who received VO, the ORR and CR were 85% and 50%, respectively. At 3 months following treatment completion, 76% and 57% of patients were MRD− in the peripheral blood and bone marrow, respectively. In patients who received VO, the most common grade 3/4 AE was neutropenia, which was seen in 53%. However, only 5% of these patients experienced grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia. TLS was reported in 3 patients from this group and all cases occurred during treatment with obinutuzumab and before treatment with venetoclax.19 The major conclusions of the CLL14 study were that the combination of VO was very tolerable, prolonging PFS compared with chlorambucil and obinutuzmab in CLL patients with comorbid conditions. Based on this study, the FDA approved VO for marketing for frontline therapy of all CLL patients on 15 May 2019.

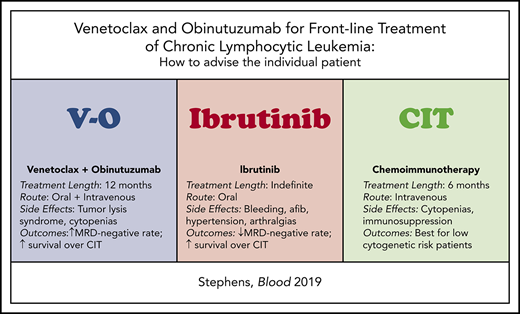

Recommending the optimal individualized frontline therapy for a CLL patient

The approval of VO has added another highly efficacious therapeutic option for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL. How does a physician advise a patient with CLL as to which is the best regimen for that specific individual? Table 2 compares key features of the currently approved regimens that should be considered when recommending frontline therapy for a patient with CLL. In particular, I want to highlight a few notable differences between the VO and ibrutinib regimens including length and administration of therapy, side-effect profile, duration of follow-up, and populations studied, and discuss recommendation of therapy by cytogenetic group and sequencing of therapy.

Comparison of key features of frontline therapy for CLL

| Treatment feature . | VO . | Ibrutinib . | Standard chemoimmunotherapy regimens (FCR, BR, OChl) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of therapy | 12 mo | Indefinite | 6 mo |

| Route of administration | Oral (venetoclax) + IV (obinutuzumab) | Oral | IV (exception: chlorambucil = oral) |

| Notable side effects | TLS, cytopenias | Bleeding, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, arthralgias | Cytopenias, immunosuppression |

| Notable drug interactions | CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers* | CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers* Anticoagulants | N/A |

| Effects on immune system | Reduction in NK cells in mouse models28 | Reconstitution of humoral and cell-mediated immune system and reduction of macrophage phagocytosis29-31 | Suppression of the humoral and cell-mediated immune system |

| Longest median follow-up on clinical trials† | 28 mo | ∼60 mo | >70 mo |

| Treatment feature . | VO . | Ibrutinib . | Standard chemoimmunotherapy regimens (FCR, BR, OChl) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of therapy | 12 mo | Indefinite | 6 mo |

| Route of administration | Oral (venetoclax) + IV (obinutuzumab) | Oral | IV (exception: chlorambucil = oral) |

| Notable side effects | TLS, cytopenias | Bleeding, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, arthralgias | Cytopenias, immunosuppression |

| Notable drug interactions | CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers* | CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers* Anticoagulants | N/A |

| Effects on immune system | Reduction in NK cells in mouse models28 | Reconstitution of humoral and cell-mediated immune system and reduction of macrophage phagocytosis29-31 | Suppression of the humoral and cell-mediated immune system |

| Longest median follow-up on clinical trials† | 28 mo | ∼60 mo | >70 mo |

N/A, not applicable; OChl, obinutuzumab + chlorambucil.

Dose modifications may be required. Consultation with a pharmacist is recommended for thorough medication review.

Assessed August 2019.

Length of therapy

VO has a fixed duration (12 months) with a goal of inducing MRD− remissions and allowing patients a period of time between therapeutic interventions. Ibrutinib therapy is indefinite (continues as long as efficacy is maintained and no intolerable toxicity is developed). This is reflected by the rarity of inducing MRD− remissions. Therefore, a patient who is not a candidate for lifelong therapy secondary to lack of compliance or patient preference may not be the best candidate for ibrutinib therapy.

Administration of therapy

Administration of VO requires 8 IV infusions of obinutuzumab. During the first month of obinutuzumab therapy and the 5-week ramp-up of venetoclax, facilities and staffing are required for rapid turnaround times to monitor TLS laboratory parameters and for careful timely review of these results. If these facilities are not available, patients should be referred to a center with these facilities to initiate therapy with VO or an alternate therapy should be chosen. Physicians not familiar with venetoclax therapy should carefully read the package insert and closely follow the directions for TLS risk assessment, prophylaxis, and management prior to administration of the drug. In contrast, ibrutinib therapy is oral and does not require IV infusions. No specific monitoring for TLS is required to initiate ibrutinib therapy.

Side-effect profile

Notable AEs after venetoclax administration are TLS and neutropenia.19 Patients with significant renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) are at higher risk for TLS, and alternative therapies than VO should be considered for these patients. If no acceptable alternative therapy is available, they should be monitored very closely for TLS in the inpatient setting during dose ramp-ups. Notable AEs with ibrutinib therapy include bleeding, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and arthralgias.5 Therefore, patients with bleeding diatheses or who require warfarin for anticoagulation should not be given ibrutinib therapy. Patients receiving other anticoagulants should be monitored very closely while on ibrutinib therapy. CLL patients with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation, hypertension, or arthralgias should be offered an alternative therapy to ibrutinib.

Duration of follow-up on clinical trials

The published clinical trials evaluating the frontline VO regimen have short median follow-up times with the longest at 28 months.19 The published clinical trials evaluating the frontline ibrutinib regimen have longer follow-up times (up to 60 months).20 Therefore, long-term efficacy, including durability of remissions, and toxicity data in patients receiving the fixed-duration VO regimen are not yet available.

Patient population studied

Although the CLL14 study gained the VO regimen approval in all patients with previously untreated CLL, the study only included patients with medical comorbidities (CIRS >6 or creatinine clearance <70 mL/min), which equated to a study population with a median age of 72 years.19 Therefore, using these data to predict outcomes for younger healthy patients is an extrapolation. The ongoing CLL13 study will provide data on a younger and healthier population of treatment-naive CLL patients receiving VO compared with standard chemoimmunotherapy or other venetoclax-based regimens (NCT02950051). In contrast, ibrutinib has been studied in CLL patients of all ages on randomized phase 3 clinical trials. It is notable that although the median ages of patients treated on the RESONATE2 and CLL14 studies were similar (73 vs 72 years), only 69% of patients treated on the RESONATE2 study had CIRS >6 or reduced creatinine clearance compared with 100% of the patients treated on the CLL14 study.5,19,21 It is also notable that the recently published E1912 study specifically evaluated an ibrutinib-based regimen in younger and healthy patients with CLL.7

Recommendation by cytogenetic group

When recommending CLL therapy for an individual patient, an important consideration is cytogenetic risk. For low cytogenetic risk patients with del(13q) and mutated IGHV, the VO, ibrutinib, and chemoimmunotherapy-based regimens all induce good clinical outcomes in this population.1,3,5-7,19 Therefore, for this group, therapy can be selected based on logistics of therapy delivery and discussion of acceptable AEs. For CLL patients with unmutated IGHV and or del(17p), administration of targeted therapies such as VO and ibrutinib have repeatedly shown prolongation in PFS when compared with chemoimmunotherapy.5,7,8 Therefore, for patients in this group, if longest response possible is a primary goal, a targeted therapy should be recommended. A note of caution specifically for patients with del(17p) is that very few data are available to guide recommendation of the VO regimen in the frontline setting. In a recent presentation of the CLL14 data, the 17 patients who received VO appear to have a 2-year PFS of ∼60%.22 Alternatively in a phase 2 study, where 51 CLL patients with del(17p) and/or TP53 dysfunction (treatment naive = 35) were treated with single-agent ibrutinib, the 2-year PFS was 82%.23 This begs the question of whether ibrutinib and/or continuous therapy will be better than fixed-duration VO for treatment of this high-risk subset. Without prospective head-to-head comparison of these agents in this setting, it remains unclear which regimen is most efficacious for all CLL subgroups, especially the patients with del(17p). Ideally, a study designed to compare frontline therapy with VO vs ibrutinib could answer many additional questions. However, partially secondary to complex business relationships between the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture venetoclax, obinutuzumab, and ibrutinib, it is unclear whether this comparison will be feasible.

Sequencing of therapy

As CLL is still considered incurable for most patients, a physician may also consider advanced planning for the sequence of future CLL therapies. At this time, data are available detailing good clinical outcomes using ibrutinib after chemoimmunotherapy and using venetoclax after ibrutinib, but no data are available detailing patient outcomes using ibrutinib or chemoimmunotherapy following venetoclax.24,25 Over time, we can expect these data to emerge. Until then, predicting outcomes of second-line therapy after frontline venetoclax is an extrapolation.

Future applications of the VO regimen

As efficacy and tolerability of the VO regimen have been established in the frontline setting for patients with CLL, the next crucial question is: could early intervention with the VO regimen in asymptomatic CLL patients improve survival compared with the standard approach of watchful waiting until development of symptomatic CLL? The US Southwest Oncology Group is planning a nationwide study to answer this exact question. This study is currently in development.

Alternative combination partners with venetoclax

Although VO is the only venetoclax combination FDA-approved for marketing for the treatment of frontline CLL, many alternative combination regimens are currently under investigation. The therapies furthest along in development are highlighted in Table 1. Although these regimens appear tolerable and efficacious in patients with treatment-naive CLL, the data have not yet matured and these regimens should not be given outside of the setting of a clinical trial. At this time, there are several ongoing large phase 3 studies for patients with previously untreated CLL to evaluate for superiority of venetoclax-based combinations when compared with standard-of-care agents (NCT02950051, NCT03462719, NCT03737981, NCT03701282).

Summary

Venetoclax is a highly effective and tolerable therapy now approved for all patients with CLL. The VO regimen provides a fixed-duration, chemotherapy-free option for patients with CLL and has been met with great enthusiasm in the CLL community. Until further prospective studies are completed, it is unclear whether alternate combinations with venetoclax or ibrutinib alone are superior to VO for frontline treatment of patients with CLL. Treating physicians have the benefit of tailoring treatment specifically to the individual patient based on treatment goals, preference for length of therapy, and side-effect profile.

Authorship

Contribution: D.M.S. collected and summarized data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.M.S. has received research funding from Gilead, Karyopharm, and Acerta.

Correspondence: Deborah M. Stephens, Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, 2000 Circle of Hope, Research South 5509, Salt Lake City, UT 84112; e-mail: deborah.stephens@hci.utah.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal