Key Points

Single-cell approaches identify regulators of malignant HSC self-renewal.

Identification of novel roles for Bmi1, Pbx1, and Meis1 in myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Abstract

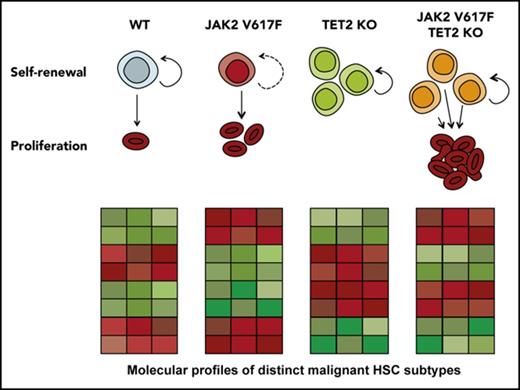

Recent advances in single-cell technologies have permitted the investigation of heterogeneous cell populations at previously unattainable resolution. Here we apply such approaches to resolve the molecular mechanisms driving disease in mouse hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), using JAK2V617F mutant myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) as a model. Single-cell gene expression and functional assays identified a subset of JAK2V617F mutant HSCs that display defective self-renewal. This defect is rescued at the single HSC level by crossing JAK2V617F mice with mice lacking TET2, the most commonly comutated gene in patients with MPN. Single-cell gene expression profiling of JAK2V617F-mutant HSCs revealed a loss of specific regulator genes, some of which were restored to normal levels in single TET2/JAK2 mutant HSCs. Of these, Bmi1 and, to a lesser extent, Pbx1 and Meis1 overexpression in JAK2-mutant HSCs could drive a disease phenotype and retain durable stem cell self-renewal in functional assays. Together, these single-cell approaches refine the molecules involved in clonal expansion of MPNs and have broad implications for deconstructing the molecular network of normal and malignant stem cells.

Introduction

Billions of blood cells are produced and destroyed each day,1 and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) must provide sufficient progenitors for hematopoiesis while also maintaining their numbers. Malignancy results from disturbances in this balance, leading to the production and expansion of HSC clones with differentiation and/or proliferation abnormalities.2-4 Genetic mutations often drive these changes and have been a major focus for cancer researchers.5

The molecular function of individual mutations and their role in disease is less clear, and the combinatorial action of multiple mutations is nearly completely uncharted. In most malignancies, there are numerous recurrent driver mutations, resulting in a wide array of mutation combinations, presenting significant challenges for discerning disease relevant biology.6 The myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are genetically less complicated than the vast majority of malignancies7 and are an excellent model for delineating the effect of mutation combinations in early tumorigenesis.8 A single acquired JAK2V617F mutation was reported to be present in most patients with MPN,9-12 and subsequent studies identified a number of recurrent mutations found to collaborate with JAK2V617F,13-15 suggesting that on its own, JAK2V617F is insufficient to initiate disease.

Several groups have developed JAK2V617F knock-in mouse models to study the effect of physiological levels of JAK2V617F (reviewed in Li et al16 ). Although not phenotypically identical, these models uniformly develop an MPN phenotype with increased myeloid cell production in the erythrocytic and/or megakaryocytic lineage, with some increases in granulocytic/monocytic lineages.16,17 These phenotypes are transplantable and can transform to more severe forms of disease (eg, myelofibrosis and/or acute myeloid leukemia). When HSC self-renewal was tested in serial transplantation experiments, HSCs from JAK2V617F knock-in models did not outcompete wild-type HSCs, again supporting the notion that JAK2V617F on its own was insufficient to initiate disease.18-20

The most commonly comutated gene in JAK2V617F-positive MPNs is TET2, where loss-of-function mutations are thought to give a clonal advantage to the HSCs.14,21,22 Recently, both a transgenic and a heterozygous JAK2V617F knock-in model were crossed with a Tet2 knock-out and formally demonstrated that loss of TET2 could confer a self-renewal advantage on JAK2V617F-mutant HSCs, resulting in a robust serially transplantable disease.23,24 The molecular basis for this self-renewal advantage in long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) remains undetermined and is complicated by heterogeneity in the HSC compartment.25

To resolve this heterogeneity and to identify which molecules drive the increased self-renewal capacity of a malignant clone, we undertook a single-cell approach. By profiling homozygous JAK2V617F-mutant HSCs in cell biological and molecular assays, we identify key HSC self-renewal regulators that were lower or absent in a subset of single-mutant HSCs. Our results highlight the power of single-cell approaches for identifying molecular profiles and for interrogating essential components responsible for each aspect of disease phenotype.

Methods

Mice

Isolation of E-SLAM HSCs, in vitro assays, and expression profiling

E-SLAM cells were isolated as described previously,26,27 and full details of their isolation and culture are found in the supplemental Methods. Single-cell gene expression analysis was performed as described previously,28-30 using the Fluidigm BioMark system, with full details in the supplemental Methods.

Bone marrow transplantation assays and analysis

Primary and secondary transplantation assays were performed as described previously20 ; full details of HSC frequencies, method of transplantation and peripheral blood analysis are in the supplemental Methods.

Overexpression assays

Small pools (1500-3600 cells) of CD45+Lin−CD150+CD48− hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) were isolated and transduced with candidate genes, as described in the supplemental Methods.

Patient stem and progenitor cell assays

Fresh blood samples were collected from patients with an MPN who had mutations in both JAK2 and TET2 diagnosed according to British Committee for Standards in Haematology guidelines. The study was approved by the Cambridge and Eastern Region Ethics Committee, and was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Details of HSPC isolation, in vitro assays, and gene expression studies are found in the supplemental Methods.

Results

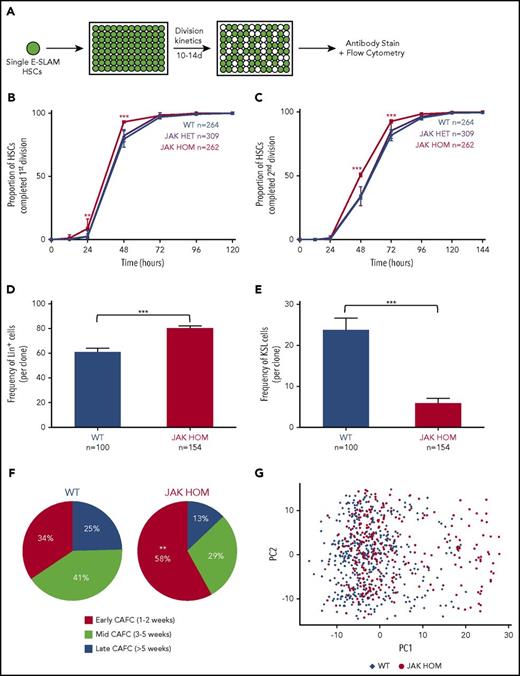

JAK2V617F drives increased proliferation and differentiation of HSCs in vitro

To determine the effect of JAK2V617F expression on single HSCs we isolated single CD45+EPCR+CD48−CD150+ (E-SLAM) cells (40%-50% HSCs by long-term transplantation studies26 ) from a knock-in mouse model expressing either 1 (JAK HET) or 2 (JAK HOM) copies of human JAK2V617F. HSCs were cultured in conditions that support HSC self-renewal (Figure 1A),31 in which cell division kinetics, colony size, and mature cell production were assessed. JAK HET HSCs did not show significant differences in early divisional kinetics or cell cycle entry, but did give rise to significantly larger clones (supplemental Figure 1A), in agreement with previous data in the inducible Mx1-Cre knock-in model.32 However, when compared with WT cells, JAK HOM HSCs exited quiescence more quickly and had shorter cell cycle transit time, with an increased proportion of HSCs (∼20%) having completed the first and second division at 48 hours compared with WT controls (Figure 1B-C; P < .0001). These data were supported by single-cell time-lapse imaging and tracking of HSCs isolated from WT and JAK HOM animals (n = 2 mice, data not shown). Assessment of clonal progeny of individual HSCs showed that colonies from JAK HOM HSCs were on average larger (supplemental Figure 1A) and more differentiated (Figure 1D) and contained proportionally fewer progenitor cells (KSL: c-Kit+, Sca1+, Lin−) (Figure 1E) than clones grown from HSCs obtained from WT littermate controls.

JAK2V617F induces increased proliferation and differentiation in single HSC-derived clones. (A) Schematic of single-cell in vitro cultures. Single CD45+EPCR+CD48−CD150+ (E-SLAM) cells were sorted into individual wells; cultured for 10 to 14 days in STEMSPAN with 10% FCS, 300 ng/mL SCF, and 20 ng/mL interleukin 11; and assessed for proliferation, cell cycle kinetics, and differentiation. (B-C) Daily cell counts revealed that JAK2V617F homozygous HSCs (red line) display faster cell cycle kinetics, as indicated by a shorter time to first and second division, P < .0001 at 48 hours (3 independent experiments). (D-E) Homozygous JAK2V617F HSCs (red bars) give rise to an increased number of differentiated cells (positive for Gr1+/Mac1+; Lin+; P ≤ .0001) and a reduced number of stem/progenitor cells (Gr1−, Mac1−, c-Kit+, Sca1+, LSK; P < .0001). WT, n = 100; JAK HET, n = 189; JAK HOM, n = 154 (3 independent experiments). (F) Compared with WT HSCs, JAK HOM HSCs have increased early-forming CAFCs (P = .0086). WT, n = 61; JAK HOM, n = 62 (2 independent experiments). Asterisks indicate significant differences by Student t test for D+E, and by χ-squared for B, C, and F (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (G) Principal component (PC) analysis of all HSCs calculated from the 39 genes analyzed. PC1 and PC2 account JAK2V617F HSCs are indicated by red circles, and WT HSCs are indicated by blue diamonds. A cluster of cells on the right hand side of the graph is enriched for JAK2V617F HOM HSCs and have reduced expression of several important hematopoietic genes (Meis1, Smarcc2, Bmi1, Pbx1, Sfpi1, Runx1, Hoxb4, Myb, Lmo2). Axes are in arbitrary units. WT, n = 465; JAK HOM, n = 277.

JAK2V617F induces increased proliferation and differentiation in single HSC-derived clones. (A) Schematic of single-cell in vitro cultures. Single CD45+EPCR+CD48−CD150+ (E-SLAM) cells were sorted into individual wells; cultured for 10 to 14 days in STEMSPAN with 10% FCS, 300 ng/mL SCF, and 20 ng/mL interleukin 11; and assessed for proliferation, cell cycle kinetics, and differentiation. (B-C) Daily cell counts revealed that JAK2V617F homozygous HSCs (red line) display faster cell cycle kinetics, as indicated by a shorter time to first and second division, P < .0001 at 48 hours (3 independent experiments). (D-E) Homozygous JAK2V617F HSCs (red bars) give rise to an increased number of differentiated cells (positive for Gr1+/Mac1+; Lin+; P ≤ .0001) and a reduced number of stem/progenitor cells (Gr1−, Mac1−, c-Kit+, Sca1+, LSK; P < .0001). WT, n = 100; JAK HET, n = 189; JAK HOM, n = 154 (3 independent experiments). (F) Compared with WT HSCs, JAK HOM HSCs have increased early-forming CAFCs (P = .0086). WT, n = 61; JAK HOM, n = 62 (2 independent experiments). Asterisks indicate significant differences by Student t test for D+E, and by χ-squared for B, C, and F (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (G) Principal component (PC) analysis of all HSCs calculated from the 39 genes analyzed. PC1 and PC2 account JAK2V617F HSCs are indicated by red circles, and WT HSCs are indicated by blue diamonds. A cluster of cells on the right hand side of the graph is enriched for JAK2V617F HOM HSCs and have reduced expression of several important hematopoietic genes (Meis1, Smarcc2, Bmi1, Pbx1, Sfpi1, Runx1, Hoxb4, Myb, Lmo2). Axes are in arbitrary units. WT, n = 465; JAK HOM, n = 277.

We next undertook Cobblestone-area-forming cell (CAFC) assays, an in vitro surrogate for HSC transplantation where test cells are cultured on a stromal cell line for more than 5 weeks and assessed for the presence of hematopoietic colonies.33 HSCs with less durable self-renewal tend to form colonies at early times.34 HSCs from JAK HOM mice gave rise to an increased number of early CAFCs and a reduced number of mid and late CAFCs (Figure 1F), suggesting that JAK HOM HSCs have altered stem cell function, in agreement with transplantation experiments showing reduced numbers of HSCs in JAK HOM mice.20 Taken together, these data show that JAK2V617F provides an advantage for progenitor cells resulting in overproduction of differentiated cells, and that this expansion comes at the expense of LT-HSC self-renewal.

Single-cell expression profiling identifies mutant HSCs with reduced expression of self-renewal regulators

To determine the molecular drivers of HSC functional abnormalities, we first performed gene expression arrays on sorted E-SLAM HSCs from WT, JAK HET, and JAK HOM mice. Although the hyperproliferation observed in progenitors could be potentially explained by modest changes in genes regulating the cell cycle, no clear differences emerged on a bulk level that could account for the loss of HSC self-renewal observed (ArrayExpress accession E-MTAB-6878). Because the data in Figure 1 identified a fraction of JAK2V617F-homozygous HSCs with aberrant behavior in vitro, single-cell gene expression profiling was performed to determine whether some mutant HSCs had altered expression of self-renewal genes. Single phenotypic HSCs from 3 JAK HOM (n = 277) and 3 WT (n = 465) mice were analyzed for the expression of 39 transcription factors and self-renewal regulators by multiplexed quantitative polymerase chain reaction (genes listed in supplemental Table 1). Principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 1G) revealed a subset of cells, in which JAK HOM cells are overrepresented, that are marked by reduced expression of Meis1, Smarcc2, Bmi1, Pbx1, Sfpi1, Runx1, Hoxb4, Myb, and Lmo2, as indicated by the loadings plot shown in supplemental Figure 2A. Single-cell analysis further shows that this subset of cells has reduced expression of most, if not all, of these regulators in each cell compared with cells in the larger cluster (supplemental Figure 2B), suggesting that reduced expression of these genes might contribute to the loss of competitive reconstitution ability observed in JAK2V617F HSCs.

Compound loss of Tet2 does not reverse JAK2V617F-induced HSC hyperproliferation

Loss of Tet2 is the most common collaborating mutation observed in JAK2V617F-positive MPNs.13 Previous studies have shown that loss of Tet2 leads to increased replating capacity in vitro and increased self-renewal in vivo.21,22 When heterozygous or transgenic JAK2V617F knock-in mice were crossed with TET2 knockout mice, an accelerated MPN phenotype was observed and BM transplantations showed a strong self-renewal advantage over WT and JAK2V617F single-mutant controls.23,24 Homozygous JAK2V617F knock-in mice have been previously documented to have a more substantial loss of HSC self-renewal20 and have not previously been combined with other mutations. To first test whether loss of TET2 function could rescue the HSC cycling and hyperproliferation phenotypes observed in Figure 1, we crossed the homozygous JAK2V617F knock-in model20 with a TET2 knock-out model21 (Figure 2A).

Loss of Tet2 does not reverse JAK2V617-induced hyperproliferation in single HSCs. (A) Table summarizing the mutations in each genotype and the color code for the remainder of the figures. (B-C) The cumulative times to first (B) and second (C) division are shown and were determined by manual daily cell counts, scoring the presence of 1, 2, or 3 to 4 cells. Loss of Tet2 on its own (green line) does not affect cell cycling compared with WT (blue line), whereas JAK2V617F on its own (red line) increases proliferation (P < .0001). Compound mutants (JAK HOM TET HOM, orange line) behave like JAK2V617F single-mutant HSCs with a faster time to first and second division, respectively (P < .0001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. WT, n = 572; JAK HOM, n = 439; TET HOM, n = 566; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 435; and are from 3-6 independent experiments. (D) Colony size after 9 days in culture. JAK2V617F and double-mutant HSCs give rise to a higher frequency (P < .0001 and < .0001) of large colonies compared with WT controls. Colonies were categorized as very small (>50), small (51-500), medium (501-10 000), or large (>10 000). WT, n = 572; JAK HOM, n = 439; TET HOM, n = 566; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 435. (E-F) After 10 days in culture, colonies were analyzed by flow cytometry for differentiation markers. Colonies with JAK2V617F (JAK HOM [red bars] and JAK HOM TET HOM [orange bars]) have an increased frequency of Lin+ cells (Ly6g+, Mac1+; JAK HOM, P < .0001; JAK HOM TET HOM, P = .0177). Double mutants (orange bars) and JAK HOM (red bars) show a reduced frequency of KSL (Ly6g−, Mac1−, c-Kit+, Sca1+) cells compared with WT (blue bars) and TET HOM (green bars; JAK HOM TET HOM, P = .001; JAK HOM, P < .0001). WT, n = 165; JAK HOM, n = 178; TET HOM, n = 154; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 145 (3 independent experiments).

Loss of Tet2 does not reverse JAK2V617-induced hyperproliferation in single HSCs. (A) Table summarizing the mutations in each genotype and the color code for the remainder of the figures. (B-C) The cumulative times to first (B) and second (C) division are shown and were determined by manual daily cell counts, scoring the presence of 1, 2, or 3 to 4 cells. Loss of Tet2 on its own (green line) does not affect cell cycling compared with WT (blue line), whereas JAK2V617F on its own (red line) increases proliferation (P < .0001). Compound mutants (JAK HOM TET HOM, orange line) behave like JAK2V617F single-mutant HSCs with a faster time to first and second division, respectively (P < .0001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. WT, n = 572; JAK HOM, n = 439; TET HOM, n = 566; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 435; and are from 3-6 independent experiments. (D) Colony size after 9 days in culture. JAK2V617F and double-mutant HSCs give rise to a higher frequency (P < .0001 and < .0001) of large colonies compared with WT controls. Colonies were categorized as very small (>50), small (51-500), medium (501-10 000), or large (>10 000). WT, n = 572; JAK HOM, n = 439; TET HOM, n = 566; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 435. (E-F) After 10 days in culture, colonies were analyzed by flow cytometry for differentiation markers. Colonies with JAK2V617F (JAK HOM [red bars] and JAK HOM TET HOM [orange bars]) have an increased frequency of Lin+ cells (Ly6g+, Mac1+; JAK HOM, P < .0001; JAK HOM TET HOM, P = .0177). Double mutants (orange bars) and JAK HOM (red bars) show a reduced frequency of KSL (Ly6g−, Mac1−, c-Kit+, Sca1+) cells compared with WT (blue bars) and TET HOM (green bars; JAK HOM TET HOM, P = .001; JAK HOM, P < .0001). WT, n = 165; JAK HOM, n = 178; TET HOM, n = 154; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 145 (3 independent experiments).

Loss of TET2 alone did not alter exit from quiescence (Figure 2B), divisional kinetics (Figure 2C), colony size (Figure 2D), or the proportion of differentiated/progenitor cells (Figure 2E-F) compared with WT controls. However when loss of TET2 was combined with JAK2V617F homozygosity, entry into cell cycle was accelerated (Figure 2B), cell cycle transit time was increased (Figure 2C), and average clone size was increased (Figure 2D), similar to the phenotypes observed in JAK2V617F-homozygous HSCs. Clones derived from double-mutant HSCs also had an increased proportion of mature lineage marker-positive cells (Figure 2E) and a decreased proportion of primitive progenitor (KSL) cells (Figure 2F). Overall, therefore, compound loss of TET2 did not rescue the JAK2V617F-induced cycling and hyperproliferation phenotypes observed in single in vitro HSC functional assays.

To validate these findings in patient samples, we isolated human Lin−CD34+CD38−CD90+CD45RA− cells (human HSCs) from patients with an MPN. Single human HSCs were cultured in stem cell maintenance conditions and divisional kinetics were tracked for 10 days. Individual clones were plated in a colony-forming cell assay for a further 14 days before being harvested for genotyping (Figure 3A), allowing retrospective assignment of mutational status. No difference was observed between TET2-mutant and nonmutant (WT) cells in the time to first or second cell division (Figure 3B-C), and both JAK2 single-mutant and JAK2/TET2 double-mutant cells had faster divisional kinetics compared with nonmutant cells, with an increased proportion having completed first and second divisions at 72 hours (JAK P < .01; JAK TET P < .001) (Figure 3B-C). However, JAK2 single-mutant and double-mutant clone size was not significantly affected compared with nonmutant cells (Figure 3D), perhaps because of the slower speed of human HSCs that take several days to begin dividing. Notably, day 10 clones derived from human HSCs with a TET2 mutation were on average smaller than nonmutant and JAK2-mutant cells (Figure 3D).

JAK2 V617F-mutant patient HSCs proliferate faster than TET2 single-mutant and nonmutant cells. (A) Schematic of experimental design. Single Lin−CD34+CD38−CD90+CD45RA− cells were sorted from MPN patient peripheral blood samples (n = 12; 3 essential thrombocythemia, 5 polycythemia vera, 4 secondary myelofibrosis) into 96-well plates, and cell counts were performed daily for 10 days. On days 9 to 10, clones were harvested and plated in a colony-forming cell assay, and the colonies produced were harvested for genotyping. Several patient assays were originally performed for a previous study46 and were pooled together with newly generated data. (B-C) Human HSCs with a TET mutation alone (n = 2 patients, green line) have similar divisional kinetics to nonmutant HSCs (blue line), whereas cells with a JAK2 V617F mutation alone (n = 10 patients, red line) or both mutations (orange lines) had a reduced time to first (B) and second (C) divisions (higher proportion completed division at 72 hours; JAK, P < .01; JAK TET, P < .001). WT, n = 114; JAK, n = 108; TET, n = 40; JAK TET, n = 183. Patients with genotyped colonies: WT, n = 11; TET alone n = 2; JAK alone, n = 11; JAK TET together, n = 8. (D) Compared with WT cells, cells with TET mutations gave rise to a higher proportion of very small clones (<50 cells; P < .0001). WT, n = 114; JAK, n = 108; TET, n = 40; JAK TET, n = 183.

JAK2 V617F-mutant patient HSCs proliferate faster than TET2 single-mutant and nonmutant cells. (A) Schematic of experimental design. Single Lin−CD34+CD38−CD90+CD45RA− cells were sorted from MPN patient peripheral blood samples (n = 12; 3 essential thrombocythemia, 5 polycythemia vera, 4 secondary myelofibrosis) into 96-well plates, and cell counts were performed daily for 10 days. On days 9 to 10, clones were harvested and plated in a colony-forming cell assay, and the colonies produced were harvested for genotyping. Several patient assays were originally performed for a previous study46 and were pooled together with newly generated data. (B-C) Human HSCs with a TET mutation alone (n = 2 patients, green line) have similar divisional kinetics to nonmutant HSCs (blue line), whereas cells with a JAK2 V617F mutation alone (n = 10 patients, red line) or both mutations (orange lines) had a reduced time to first (B) and second (C) divisions (higher proportion completed division at 72 hours; JAK, P < .01; JAK TET, P < .001). WT, n = 114; JAK, n = 108; TET, n = 40; JAK TET, n = 183. Patients with genotyped colonies: WT, n = 11; TET alone n = 2; JAK alone, n = 11; JAK TET together, n = 8. (D) Compared with WT cells, cells with TET mutations gave rise to a higher proportion of very small clones (<50 cells; P < .0001). WT, n = 114; JAK, n = 108; TET, n = 40; JAK TET, n = 183.

Together, these data show in both mouse models and patient samples that JAK2V617F increases proliferation of primary HSCs in the presence or absence of a TET2 mutation, and that TET2 loss on its own does not confer a proliferation advantage on HSCs in vitro.

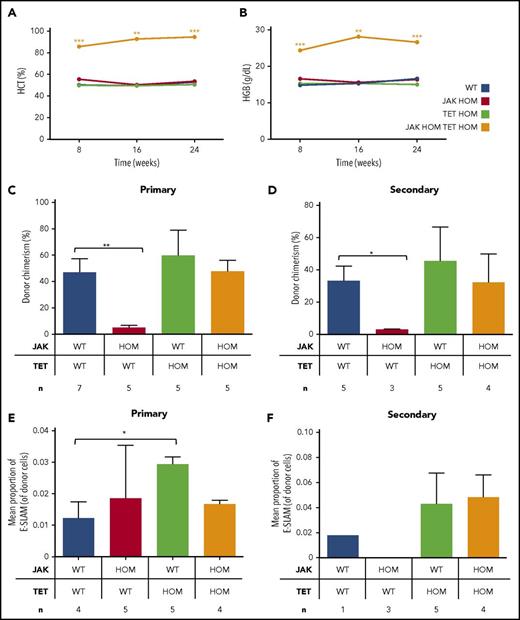

Homozygous JAK2V617F combined with loss of TET2 drives a robust transplantable myeloproliferative phenotype in vivo

Competitive transplantation was undertaken to assess the relative ability of bone marrow (BM) cells from each genotype to initiate an MPN phenotype. Despite a red cell phenotype in the steady state JAK HOM mouse, an MPN phenotype is not observed in transplantation experiments using low cell numbers,20 likely because of low levels of donor cell repopulation. Loss of Tet2 on its own was also insufficient to give an MPN phenotype, although donor cell repopulation was quite high throughout the experiment. In combination, low cell numbers of double-mutant BM were sufficient to drive a robust serially transplantable MPN phenotype, where hyperproliferation combined with high donor chimerism to give persistently high hematocrit (Figure 4A) and hemoglobin (Figure 4B) levels, even at limiting cell doses (supplemental Figure 3), and the phenotype was sustained in secondary transplantations (supplemental Figure 4). No consistent significant differences were observed in other blood cell parameters throughout the transplantation experiments, although recipient numbers were not sufficient to exclude the possibility of mild differences or heterogeneous phenotypes.

Double JAK/TET mutant cells have a clonal advantage and result in a sustained myeloproliferative phenotype in transplantation. Bone marrow transplantations were performed, and peripheral blood was analyzed for donor cell chimerism and blood parameters. Only recipients of double-mutant bone marrow have persistently high hematocrit (A) (P < .01 at 16 weeks) and hemoglobin (B) (P < .01 at 16 weeks). Donor cell chimerism at 16 weeks in primary (C) and secondary (D) transplantations is displayed. Whereas JAK2V617F cells (red bars) are less competitive relative to WT cells (blue bars; P < .01), those with a single TET mutation (green bars) or double mutants (JAK HOM TET HOM, orange bars) were similar to WT cells, indicating no deficiency in self-renewal. (E-F) Mean proportion of E-SLAM HSCs in donor cells in bone marrow, 24 weeks posttransplantation, from primary (E) and secondary (F) recipients. In double-mutant recipients, E-SLAM numbers were not different compared with WT, whereas JAK2 single-mutant recipients have lost both phenotypic and functional HSCs.

Double JAK/TET mutant cells have a clonal advantage and result in a sustained myeloproliferative phenotype in transplantation. Bone marrow transplantations were performed, and peripheral blood was analyzed for donor cell chimerism and blood parameters. Only recipients of double-mutant bone marrow have persistently high hematocrit (A) (P < .01 at 16 weeks) and hemoglobin (B) (P < .01 at 16 weeks). Donor cell chimerism at 16 weeks in primary (C) and secondary (D) transplantations is displayed. Whereas JAK2V617F cells (red bars) are less competitive relative to WT cells (blue bars; P < .01), those with a single TET mutation (green bars) or double mutants (JAK HOM TET HOM, orange bars) were similar to WT cells, indicating no deficiency in self-renewal. (E-F) Mean proportion of E-SLAM HSCs in donor cells in bone marrow, 24 weeks posttransplantation, from primary (E) and secondary (F) recipients. In double-mutant recipients, E-SLAM numbers were not different compared with WT, whereas JAK2 single-mutant recipients have lost both phenotypic and functional HSCs.

In both the primary (Figure 4C) and secondary (Figure 4D) transplantations, recipients of JAK HOM BM have low donor chimerism at 16 weeks posttransplantation, in line with previous data, in which low numbers (eg, 1-5 × 105) of BM cells were transplanted.20 Recipients of TET HOM BM, in contrast, were successfully repopulated through both primary and secondary transplantations, comparable to WT BM transplantation. Recipients of double-mutant (JAK HOM TET HOM) BM also show persistent donor cell contribution similar to WT, demonstrating that TET2 loss rescues the HSC disadvantage observed in JAK HOM BM. Of note, the frequency of phenotypic E-SLAM HSCs in donor cell suspensions was highest in TET KO mice.

These transplantation data were further supported by the number of phenotypic HSCs present in BM samples in primary and secondary recipients (Figure 4E-F). Notably, although primary recipients of JAK HOM BM had a normal number of phenotypic HSCs, these cells were clearly unable to repopulate secondary recipients (Figure 4F). Finally, we performed a limiting dilution transplantation assay to determine the minimal number of double-mutant cells required to initiate disease. Chimerism levels were similar to transplantations of WT BM cells (supplemental Figure 3A) and doses of 100 000 and 50 000, but not 10 000, double-mutant cells were able to sustain a red cell phenotype up to 3 months (supplemental Figure 3B). These results estimate the disease-initiating cell frequency as ∼1 in 33 000 double-mutant WBM cells, a number similar to the expected LT-HSC frequency in normal BM (1 in 20 000).

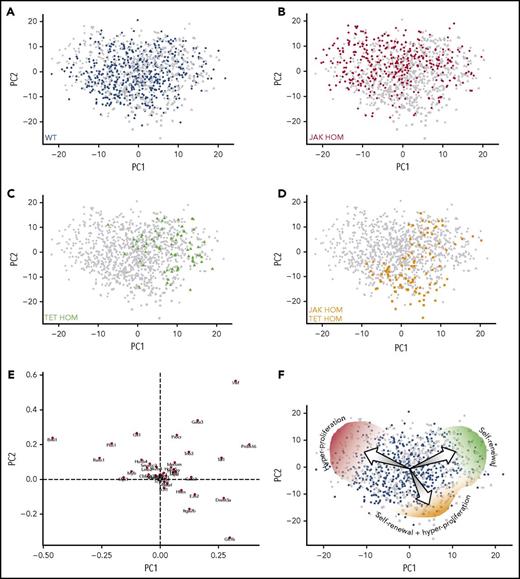

Single- and double-mutant HSCs have distinct molecular profiles of self-renewal regulators

To understand the molecular mechanism of increased self-renewal that TET2 loss confers on JAK2 mutant HSCs, single-cell gene expression profiling was performed on TET2 single-mutant (TET HOM, n = 73) and double-mutant (JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 99) HSCs, and these were compared with WT (n = 561) and JAK HOM (n = 376) HSCs (supplemental Figure 5). Hierarchical clustering shows 5 broad molecular clusters of cells (supplemental Figure 5A). Clusters I and II are significantly enriched (P < .05 and P < .005) for JAK HOM HSCs, Cluster III is significantly enriched (P < .001) for TET HOM HSCs, and Cluster IV is significantly enriched for WT (P < .05) and double-mutant cells (P < .05). Interestingly, Cluster II does not have any TET single- or double-mutant HSCs, a result reinforced by the PCA in individual mice (supplemental Figure 6).

Single HSCs of all genotypes were next displayed on a single PCA plot and t-SNE analysis to help visualize molecular clusters and identify the genes driving the differences (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 7A). WT HSCs existed in all regions of the molecular landscape, whereas JAK HOM HSCs were overrepresented in a specific region (Figure 5B, top left), and this region was almost completely devoid of cells lacking TET2 expression, suggesting it is a unique molecular region exclusive to a minority of WT HSCs and a larger proportion of JAK HOM HSCs. The majority of these cells are also found in Cluster II described here. The single-mutant TET HOM HSCs (Figure 5C) are predominantly found in a single area of the PCA plot (top right), and the double-mutant HSCs are enriched in a different region (Figure 5D, bottom right), although a small fraction of double-mutant cells are also found with the single-mutant TET HOM HSCs. The genes negatively associated with each of these regions are indicated in the loadings plot (Figure 5E), implicating genes such as Bmi1, Runx1, and Pbx1 as being involved in the self-renewal of HSCs (ie, associated with TET HOM and double-mutant genotypes), rather than proliferation (ie, associated with JAK HOM HSCs). The individual expression patterns of these genes across genotypes is displayed by violin plots in supplemental Figure 7B. We also assessed gene expression levels in CD34+CD38− HSC-enriched cell fractions from primary patient samples bearing JAK2V617F and/or TET2 mutations for these candidates and did not observe genotype-specific increases in these candidates (supplemental Figure 8). This mirrors our results in the mouse, where bulk studies could not detect differences, and is also complicated by the large number of non-HSCs and nonmutated cells in the CD34+CD38− fraction.

Single-cell gene expression profiling reveals distinct molecular clusters of single and double-mutant HSCs with altered self-renewal and proliferation. Cells from all 4 genotypes were assessed by single-cell multiplexed quantitative polymerase chain reaction; each PCA plot displays all single cells analyzed (with 1 population highlighted in each plot). (A-D) PCA displays on a single plot, HSCs from WT (n = 561, blue circles), JAK HOM (n = 376, red circles), TET HOM (n = 73, green circles), and JAK HOM TET HOM (n = 99, orange circles). Notably, WT cells are present across the entire molecular landscape, whereas single- and double-mutant HSCs are enriched in specific regions. (E) Loadings plot for PCA, indicating the key defining molecular features of each region, with the distance from the center indicating the negative correlation with a cell type (eg, cells in the top right lack Vwf). (F) Illustration depicting the different cell characteristics associated with each region of the molecular landscape.

Single-cell gene expression profiling reveals distinct molecular clusters of single and double-mutant HSCs with altered self-renewal and proliferation. Cells from all 4 genotypes were assessed by single-cell multiplexed quantitative polymerase chain reaction; each PCA plot displays all single cells analyzed (with 1 population highlighted in each plot). (A-D) PCA displays on a single plot, HSCs from WT (n = 561, blue circles), JAK HOM (n = 376, red circles), TET HOM (n = 73, green circles), and JAK HOM TET HOM (n = 99, orange circles). Notably, WT cells are present across the entire molecular landscape, whereas single- and double-mutant HSCs are enriched in specific regions. (E) Loadings plot for PCA, indicating the key defining molecular features of each region, with the distance from the center indicating the negative correlation with a cell type (eg, cells in the top right lack Vwf). (F) Illustration depicting the different cell characteristics associated with each region of the molecular landscape.

The single-cell profiling provides molecular evidence of distinct HSC states, and these profiles parallel the unique functional features of HSCs with different genotypes: JAK HOM HSCs can exist in a hyperproliferative, primed state that exits quiescence more rapidly; TET HOM HSCs are in a slow-dividing, durably self-renewing state; and the majority of double-mutant HSCs are both highly proliferative and possess durable self-renewal (Figure 5F). Because each distinct molecular profile could be identified in WT HSCs, although sometimes at a low frequency, these data suggest that WT HSCs are a heterogeneous mix of cells in distinct proliferative and self-renewing states. JAK2 and TET2 mutations disrupt the balance of HSC molecular subtypes by restricting the number of HSC states and, subsequently, via their downstream progeny, lead to an MPN phenotype.

Overexpression of Bmi1, Pbx1, or Meis1 can sustain an MPN phenotype in JAK HOM HSCs in vivo

Because these experiments were performed on single HSCs, the clustering diagram and differential enrichment by genotype (supplemental Figure 5A-B), in combination with the loadings plot (Figure 5E), can be used to identify which genes might define molecular subtypes and identify candidates for rebalancing the HSC pool. For example, double-mutant cells (which have restored self-renewal but still proliferate rapidly) cluster away from JAK HOM single-mutant cells (which have high proliferation but lack durable self-renewal), allowing us to narrow the list of candidate genes that drive the self-renewal advantage (eg, increased Bmi1, Pbx1, Runx1, and Gfi1 and decreased Gfi1b and Dnmt3a). Assessment of individual cells in the clustering diagram (supplemental Figure 5A) confirm these genes are downregulated or absent in single JAK HOM HSCs.

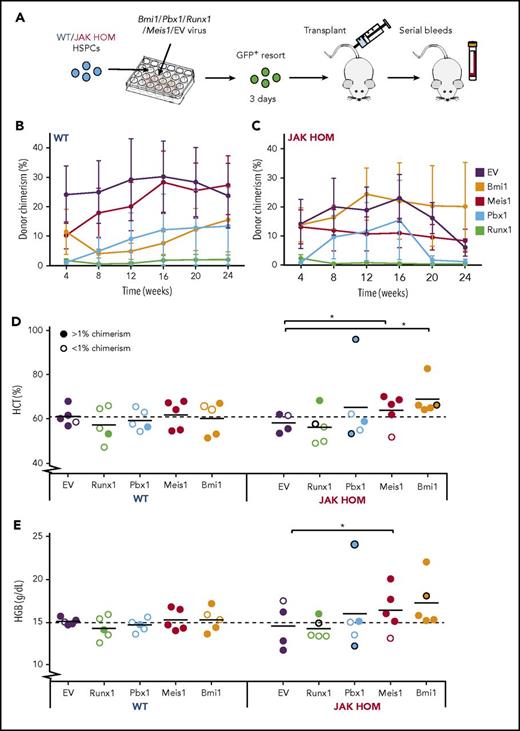

To test which genes might modulate the self-renewal of JAK HOM HSCs, we performed lentiviral overexpression and transplantation assays. CD45+Lin−CD150+CD48− HSPCs isolated from either JAK HOM or WT mice were transduced with a lentivirus containing a GFP reporter and the Bmi1, Pbx1, Runx1, or Meis1 genes. Three days postinfection, cells were re-sorted for presence of GFP and transplanted into recipient mice to monitor for disease phenotype (Figure 6A).

Overexpression of Bmi1, Meis1, and Pbx1 in JAK2-mutant HSCs enhance MPN-like phenotype in vivo. (A) Schematic of candidate gene overexpression transplants. Bulk CD45+Lin−CD48−CD150+ (HSPC) cells (300-800 per mouse) were sorted from WT and JAK HOM mice and infected with lentivirus carrying no gene (empty vector) or lentivirus carrying genes to overexpress Bmi1, Pbx1, Runx1, or Meis1 (2 independent experiments). Three days after infection, GFP+ cells (300-2000) were isolated and transplanted into recipient mice. Serial analysis of peripheral blood was performed to assess chimerism (B-C, n = 4-5 recipients) and blood cell parameters (D-E). Hematocrit (Hct) and hemoglobin (Hgb) at 20 weeks posttransplantation for JAK HOM cells overexpressing each gene compared with WT cells transduced with the same construct (D-E). Successfully repopulated JAK HOM cells overexpressing either of Meis1 or Bmi1 display an erythrocytic phenotype compared with JAK HOM cells transduced with the empty vector. *P < .05. A dark circle indicates a mouse that died before the 20-week point (unrelated to transplantation in the mouse receiving Runx1-transduced cells or the mouse receiving nonrepopulating Pbx1-transduced cells).

Overexpression of Bmi1, Meis1, and Pbx1 in JAK2-mutant HSCs enhance MPN-like phenotype in vivo. (A) Schematic of candidate gene overexpression transplants. Bulk CD45+Lin−CD48−CD150+ (HSPC) cells (300-800 per mouse) were sorted from WT and JAK HOM mice and infected with lentivirus carrying no gene (empty vector) or lentivirus carrying genes to overexpress Bmi1, Pbx1, Runx1, or Meis1 (2 independent experiments). Three days after infection, GFP+ cells (300-2000) were isolated and transplanted into recipient mice. Serial analysis of peripheral blood was performed to assess chimerism (B-C, n = 4-5 recipients) and blood cell parameters (D-E). Hematocrit (Hct) and hemoglobin (Hgb) at 20 weeks posttransplantation for JAK HOM cells overexpressing each gene compared with WT cells transduced with the same construct (D-E). Successfully repopulated JAK HOM cells overexpressing either of Meis1 or Bmi1 display an erythrocytic phenotype compared with JAK HOM cells transduced with the empty vector. *P < .05. A dark circle indicates a mouse that died before the 20-week point (unrelated to transplantation in the mouse receiving Runx1-transduced cells or the mouse receiving nonrepopulating Pbx1-transduced cells).

The transplantation of limiting doses of JAK2-mutant cells gives a phenotype (higher hematocrit and hemoglobin) that fades over time as donor chimerism is reduced because of an HSC self-renewal defect.20 As expected, both WT and JAK HOM HSPCs infected with an empty vector lentivirus had a comparable engraftment (Figure 6B-C, purple line), but the JAK HOM chimerism started to decrease after 16 weeks posttransplantation, and no phenotype was visible at late points (Figure 6D-E), most likely as a result of donor HSC exhaustion. Runx1 overexpression drove both WT and JAK HOM cells to differentiate, with 8 of 10 mice showing no almost donor cell contribution at 24 weeks posttransplantation (Figure 6B-C).

Some mice transplanted with JAK2-mutant cells overexpressing Meis1 (1 of 5) or Pbx1 (2 of 5) did not sustain donor repopulation out to 24 weeks, whereas all mice overexpressing Bmi1 (5 of 5) were successfully repopulated. Because 3-day HSPC-derived cultures represent a mix of HSCs and progenitors, it is possible that the Meis1 and Pbx1 failed grafts were the result of an inability to drive disease from a transduced progenitor cell, whereas Bmi1 may be able to sustain donor repopulation from a broader range of cell targets. Overexpression of Meis1, Pbx1, or Bmi1 in JAK2-mutant HSPCs resulted in hematopoietic phenotypes and, in some cases, resulted in the premature death of recipient animals (1 Bmi1, 1 Pbx1). Blood samples taken before death revealed high hematocrit and hemoglobin in both cases, and postmortem examination revealed splenomegaly in the mouse receiving Bmi1-transduced cells. Repopulated mice from both Meis1-transduced and Bmi1-transduced JAK2-mutant cells sustained a red cell phenotype, as indicated by significant increases in hematocrit (0.028 Bmi1; 0.012 Meis1) and hemoglobin (0.056 Bmi1; 0.044 Meis1). Together, these data show that increased Bmi1 expression, and to a lesser extent Meis1 and Pbx1, can cooperate with JAK2V617F to initiate and sustain a myeloproliferative phenotype.

Discussion

For a leukemia to develop and maintain itself from a single HSC, the HSC and its progeny must be able to thrive relative to the endogenous set of nonmalignant HSCs. The self-renewal and proliferation capacity of each HSC type are therefore critical properties to understand. Using single-cell gene expression profiling in combination with single-cell in vitro assays and genetic rescue experiments, this study identifies which self-renewal regulators are involved in partnering with JAK2V617F to drive a myeloid malignancy. We identify distinct molecular profiles that correlate with observed HSC functional properties in mouse models and primary patient samples in which JAK2V617F drives hyperproliferation, TET2 loss increases self-renewal, and double-mutant HSCs have increased self-renewal and hyperproliferation. Finally, we test several candidates functionally and reveal a novel role for Bmi1 in sustaining the malignant HSC population.

Several knock-in mouse models have been used to study the effect of JAK2V617F on self-renewal of HSCs by undertaking secondary transplantation experiments.18-20 Each of these studies showed that heterozygous JAK2V617F on its own did not confer a self-renewal advantage to HSCs in competitive secondary transplantations. Three possible explanations for the HSC self-renewal defect uniquely observed in our JAK HOM model are that this is the only model completely lacking WT JAK2 in the HSCs tested in competitive serial transplantations; our model expresses human, not mouse, JAK2V617F which might result in different biological consequences; and HSC regulator expression (eg, Bmi1, Pbx1, Meis1, etc) could be different in other knock-in models. Overall, the lack of advantage in competitive serial transplantations suggests that collaborating hits are required to give a long-term advantage over nonmutant HSCs. These data were further supported by patient-derived xenograft experiments that showed that HSCs from patient samples were able to sustain long-term engraftment if they had both TET2 and JAK2 mutations compared with those with a JAK2 mutation alone.14 Evidence for genetic collaboration with JAK2V617F in mouse models was recently published,23 where TET2 knockout mice were crossed with heterozygous JAK2V617F knock-in mice,35 resulting in a serially transplantable, highly competitive myeloproliferative disease, but the molecular and cellular basis for this interaction in HSCs remained unclear. On its own, homozygous JAK2V617F expression in knock-in mice was shown to induce an MPN phenotype at steady-state, but disease could not be sustained in a transplantation setting because of a strong self-renewal defect.20 Our study demonstrates that even this strong HSC self-renewal defect could be rescued by loss of TET2 and reveals the cellular consequences of JAK2 and/or TET2 mutations at single-cell resolution.

Our single-cell approach further delineates the key molecular players for maintaining malignant HSCs and JAK2V617F-induced disease, while isolating for the first time the specific molecular drivers of mutant HSC proliferation and self-renewal. Approximately 25% of the JAK HOM HSCs lack the key self-renewal regulators identified in this study, meaning that as a population, there is a constant interplay between these 2 states. One potential explanation for the increased proportion of cells lacking HSC self-renewal regulators in the JAK2 homozygous mouse is that the phenotypic LT-HSC gate (E-SLAM) captures a different proportion of HSCs compared with contaminating progenitors than its wildtype littermates (eg, there are more contaminating non-HSCs). Several lines of evidence suggest this would not be the case, including the similar reduction in HSC number using an alternative sorting gates (Lin−Sca1+Kit+CD34−Flk2−19) and the observation that HSCs with similar molecular programs are present in WT mice (albeit at a lower frequency), but not in the TET KO or double-mutant cells (Figure 5). In either case, as our molecular study represents a static picture taken at a single developmental stage (3-4 months) and does not give any information regarding the dynamics of the HSC compartment, it is not currently possible to resolve the relationship of impaired to nonimpaired HSCs, and we cannot yet ask questions of primacy or relatedness.

Functional studies in vivo showed that Runx1 overexpression resulted in HSC exhaustion in both WT and JAK HOM cells. In contrast, each of Meis1, Pbx1, and Bmi1 showed some form of hematopoietic phenotype when overexpressed in JAK HOM cells, ranging from a lethal hematologic disease to sustained increases in hematocrit and hemoglobin. Bmi1 overexpression in JAK HOM cells was the most robust, resulting in a more sustained HSC repopulation and a consistent MPN phenotype, aligning with previous studies that demonstrated that Bmi1 overexpression drives a robust self-renewal increase in primary HSCs.36 Notably, the phenotype is not as strong as the JAK2/TET2 double-mutant mouse, which may indicate that a combination of genes is required or that TET2 loss alters the epigenetic landscape necessary for MPN development.

Of note, Bmi1 expression was not changed in the CD34+CD38− HSC-enriched fraction of MPN patient samples with JAK2 and TET2 mutations; this could be because the vast majority of cells are non-HSCs, nonmutant cells with normal expression levels mask any changes in Bmi1, or that Bmi1 levels only change on transformation to more severe disease (eg, acute myeloid leukemia). The latter would be consistent with the fact that Bmi1 is upregulated in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and acute myeloid leukemia and is associated with a worse prognosis,37-40 suggesting that increased Bmi1 expression may play a role in advanced disease stages.

Our data suggest that a JAK2V617F mutation would not be sufficient to initiate disease on its own; however, a substantial cohort of JAK2V617F-positive patients with MPN with no known additional driver mutation do exist.13 If JAK2V617F does not give an intrinsic self-renewal advantage, some additional factor or factors likely influence a JAK2-mutant HSC’s outgrowth relative to the other HSCs in the body. Several possible explanations exist, including additional genetic or epigenetic drivers not yet identified by exome sequencing (eg, lncRNAs, enhancer elements, etc), inherited genetic risk factors in which some patients are more susceptible to cells gaining a clonal advantage because of defective nonmutant HSCs, and microenvironmental factors (the physical niche itself or secreted cytokines) that encourage the outgrowth of mutant subclones.41,42 It is also interesting to note that JAK2V617F mutations are found in a substantial percentage of older individuals with no obvious blood phenotype.43-45 This latter finding is consistent with a low number of JAK2V617F HSCs without a significant clonal advantage giving rise to more mature cells on a per-HSC basis, but an insufficient number to create an observable phenotype in an individual.

Single-cell technologies at the cell biological and molecular level have now reached a level at which more sophisticated questions about the molecules operating individually or collaboratively can be asked in mouse models of disease and, to a lesser extent, in patient samples. Combinatorial studies of HSCs from mouse models with distinct and easily assayable properties permit dissection of molecular programs of each biological phenotype. These studies set the stage for targeting molecules that might guide HSC fate choice at the population level to restore balance throughout the hematopoietic system.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Reiner Schulte, Chiara Cossetti, Gabriela Grondys-Kotarba, and Michal Maj in the Flow Cytometry Facility of the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research and Richard Grenfell and Mateusz Strzelecki in the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute Flow Cytometry core for technical assistance and suggestions; the Central Biomedical Services staff for animal housing and care; Gerald de Haan for the Flask BM Dexter-1 cell line (FBMD-1) and CAFC assay expertise; Anna Godfrey, Christina Ortmann, and Brian Huntly for providing patient samples; and Hugo Bastos, Edwin Chen, Rebecca Caesar, Joaquina Delas Vives, Priyanka Tibarewal, Fernando Calero-Nieto, Elisa Laurenti, and Victoria Moignard for helpful suggestions and discussion. M.S.S. is the recipient of a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Industrial Collaborative Awards in Science and Engineering PhD Studentship, and C.A.O. and J.F. are recipients of Wellcome Trust PhD Studentships. Work in the D.G.K. laboratory is supported by a Bloodwise Bennett Fellowship (15008), a European Hematology Association Non-Clinical Advanced Research Fellowship, and an ERC Starting Grant (ERC-2016-STG–715371). Work in the A.R.G. laboratory is supported by the Wellcome Trust, Bloodwise, Cancer Research UK, the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America. D.G.K., B.G., and A.R.G. are all supported by a core support grant from the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council to the Wellcome MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, the Cambridge Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre. A.R. is supported by a National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant (R35 CA21004).

Authorship

Contribution: M.S.S., Juan Li, N.K.W., D.L., T.S., A.R.G., and D.G.K. conceived of and designed the experiments; M.S.S., Juan Li, N.K.W., C.A.O., Jiangbing Li, M.B., J.F., D.L., J.C.M.P., D.C.P., T.L.H., and D.G.K. performed the experiments; M.S.S., Juan Li, N.K.W., Jiangbing Li, D.C.P., and D.G.K. analyzed the data; A.R. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; and M.S.S. and D.G.K. wrote the paper with input from D.L., T.S., B.G., and A.R.G.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.R. is on the scientific advisory board of Cambridge Epigenetix. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David G. Kent, Wellcome MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, Clifford Allbutt Building, University of Cambridge, Hills Rd, Cambridge, CB2 0AH, United Kingdom; e-mail: dgk23@cam.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

M.S.S. and Juan Li contributed equally to this study.

A.R.G. and D.G.K. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 2. Loss of Tet2 does not reverse JAK2V617-induced hyperproliferation in single HSCs. (A) Table summarizing the mutations in each genotype and the color code for the remainder of the figures. (B-C) The cumulative times to first (B) and second (C) division are shown and were determined by manual daily cell counts, scoring the presence of 1, 2, or 3 to 4 cells. Loss of Tet2 on its own (green line) does not affect cell cycling compared with WT (blue line), whereas JAK2V617F on its own (red line) increases proliferation (P < .0001). Compound mutants (JAK HOM TET HOM, orange line) behave like JAK2V617F single-mutant HSCs with a faster time to first and second division, respectively (P < .0001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. WT, n = 572; JAK HOM, n = 439; TET HOM, n = 566; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 435; and are from 3-6 independent experiments. (D) Colony size after 9 days in culture. JAK2V617F and double-mutant HSCs give rise to a higher frequency (P < .0001 and < .0001) of large colonies compared with WT controls. Colonies were categorized as very small (>50), small (51-500), medium (501-10 000), or large (>10 000). WT, n = 572; JAK HOM, n = 439; TET HOM, n = 566; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 435. (E-F) After 10 days in culture, colonies were analyzed by flow cytometry for differentiation markers. Colonies with JAK2V617F (JAK HOM [red bars] and JAK HOM TET HOM [orange bars]) have an increased frequency of Lin+ cells (Ly6g+, Mac1+; JAK HOM, P < .0001; JAK HOM TET HOM, P = .0177). Double mutants (orange bars) and JAK HOM (red bars) show a reduced frequency of KSL (Ly6g−, Mac1−, c-Kit+, Sca1+) cells compared with WT (blue bars) and TET HOM (green bars; JAK HOM TET HOM, P = .001; JAK HOM, P < .0001). WT, n = 165; JAK HOM, n = 178; TET HOM, n = 154; JAK HOM TET HOM, n = 145 (3 independent experiments).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/132/8/10.1182_blood-2017-12-821066/4/m_blood821066f2.jpeg?Expires=1769117251&Signature=nZhznTj7sQvsUVl7g3-3le5rO~~AfHyukhLLNYqmbQTvabfEavn0uM9ATRaoPfOv1kWAYtF~XLbSjY63th-bAeLbcdCL-~D9uSBuLh6FW5mGlsC5JoPSeZfmRJDU1LInG6zC~Sfw1A9YWVsIZGMXBnD6WMRsPZNc9YyN64X-q3SNpsY7NQnGC9f7GzjqDl3ubDcblmq8tL5OZFuYdntuT4x7Vq7kLdMH8Y9XSr9LyWmjmqq73xFqmWhCsZP-IaDvSOJTRX~hAJwgMfRj187FrSP4M1nMTL00VZwPf7JNvS0Br~BFC7G3Bh0L7olx~NU6VIdVA-ulen8KIkAKmzY0yA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal