Key Points

ERFE suppresses BMP/SMAD signaling in vitro and in vivo.

ERFE inhibits hepcidin induction by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7.

Abstract

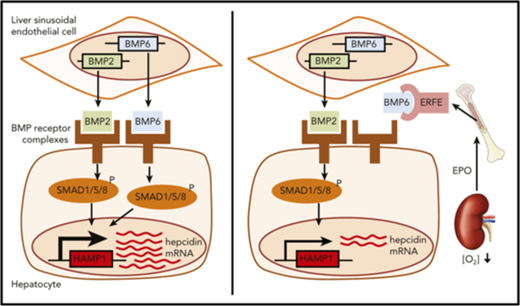

Decreased hepcidin mobilizes iron, which facilitates erythropoiesis, but excess iron is pathogenic in β-thalassemia. Erythropoietin (EPO) enhances erythroferrone (ERFE) synthesis by erythroblasts, and ERFE suppresses hepatic hepcidin production through an unknown mechanism. The BMP/SMAD pathway in the liver is critical for hepcidin control, and we show that EPO suppressed hepcidin and other BMP target genes in vivo in a partially ERFE-dependent manner. Furthermore, recombinant ERFE suppressed the hepatic BMP/SMAD pathway independently of changes in serum and liver iron. In vitro, ERFE decreased SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8 phosphorylation and inhibited expression of BMP target genes. ERFE specifically abrogated the induction of hepcidin by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7 but had little or no effect on hepcidin induction by BMP2, BMP4, BMP9, or activin B. A neutralizing anti-ERFE antibody prevented ERFE from inhibiting hepcidin induction by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. Cell-free homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assays showed that BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7 competed with anti-ERFE for binding to ERFE. We conclude that ERFE suppresses hepcidin by inhibiting hepatic BMP/SMAD signaling via preferentially impairing an evolutionarily closely related BMP subgroup of BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. ERFE can act as a natural ligand trap generated by stimulated erythropoiesis to regulate the availability of iron.

Introduction

Iron absorption is tightly regulated by erythropoietic demand via control of hepcidin expression.1 Hepcidin inhibits the cellular iron exporter ferroportin,2,3 which reduces iron recycling through splenic macrophages and uptake of dietary iron through enterocytes. When iron is required after acute blood loss or because of hypoxia, hepcidin is suppressed to allow iron mobilization for increased erythropoiesis.4 Erythropoietin (EPO) causes hepcidin suppression,5-7 at least in part by increasing synthesis of the hormone erythroferrone (ERFE).8 ERFE is produced by erythroblasts after bleeding or EPO treatment and acts on hepatocytes to suppress hepcidin expression. Erfe knockout (KO) mice fail to suppress hepcidin after phlebotomy and show delayed recovery from blood loss.8 Furthermore, serum ERFE concentrations are increased in humans after blood loss and EPO administration and in β-thalassemia patients.9 Hepcidin expression is modulated via the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway10-12 : BMPs bind to BMP receptors on hepatocyte cell membranes that phosphorylate cytosolic SMADs (SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8) that translocate to the nucleus complexed with SMAD4 to activate the transcription of target genes, including hepcidin (HAMP).11 Here we demonstrate that ERFE directly inhibits the induction of hepcidin expression by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7.

Study design

Details of the our study methods are found in supplemental Data (available on the Blood Web site). Briefly, experiments were performed in 9- to 13-week-old wild-type (WT) and Erfe KO male mice. Either recombinant human EPO 200 IU or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally once per day for 3 consecutive days, and analysis was performed 24 hours after the last injections. A single dose of either recombinant mouse ERFE 200 µg or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally, and analysis was performed 3 hours after treatment. Blood parameters were quantified using a hematology analyzer. Serum and non-heme liver iron were quantified as previously described.13

Cell treatments

Huh7 and HepG2 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium-high glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamine, unless otherwise indicated. Cells were plated 24 hours before treatments and treated for 30 minutes, 6 hours, or 24 hours.

RNA isolation and sequencing

RNA was isolated by using an RNeasy Plus kit (QIAGEN). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was undertaken using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix and Expression Assays (supplemental Table 1). RNA was converted into biotin-labeled complementary RNA for hybridization and was analyzed using the Human HT12v4.0 Expression Beadchip (Illumina) and an iScan Scanner (Illumina). Raw data were normalized using the lumi package and compared using LIMMA (Bioconductor). Messenger RNA (mRNA) sequencing libraries were constructed from 1 µg of total RNA with Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform at single-end 75 bp.

Assays and statistical analysis

Western blot was performed as described.14 Antibodies used were anti-phosphorylated SMAD (pSMAD)1/5/9, anti-SMAD1, anti-β-actin-peroxidase and anti-rabbit-IgG HRP-conjugated. C2C12 BRE-Luc cells were obtained and cultured as described.15 Cells were treated with BMP (2 nM) alone or in combination with mouse ERFE (7.5 pM-0.5 µM) in 1% fetal bovine serum. Luminescence was measured 24 hours after treatment using the britelite plus Reporter Gene Assay System. For homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence, the reaction mix contained 15 nM biotinylated murine ERFE, SA-XL665, europium cryptate-labeled antibody, and BMPs (0.1-200 nM) incubated for 3 hours at room temperature and read on the EnVision Multilabel Plate Reader (excitation, 340 nm; emission, 615 nm and 665 nm). Statistical significance was assessed by Student t test or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey test using Prism 6 GraphPad. Microarray data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE118367. RNA sequencing data are available at the Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP156963.

Results and discussion

Mice challenged with EPO or Erfe downregulate hepatic BMP target genes

First we tested the effect of EPO treatment in WT and Erfe KO mice. WT mice displayed enhanced erythropoiesis with a blunted or no effect in Erfe KO mice (supplemental Figure 1). WT and Erfe KO mice had similar hepcidin expression at baseline as previously reported.8 EPO strongly suppressed hepatic Hamp and other Bmp target genes (Id1, Id2, Atoh8, and Smad7), indicating decreased BMP-signaling activity (Figure 1A). In Erfe KO mice, suppression of Hamp, Id2, and Atoh8 was blunted or prevented, suggesting that the effect of EPO on Bmp signaling is partially Erfe dependent. The Erfe-independent decrease in hepatic Bmp signaling may be explained by increased iron consumption by EPO-stimulated erythroblasts, leading to decreased transferrin saturation (Figure 1B). To dissociate between the effects of Erfe and iron on hepatic BMP signaling, we injected recombinant murine Erfe protein into WT mice and performed analysis 3 hours later, at which time point serum and liver iron were unchanged (Figure 1C). Erfe suppressed hepatic Hamp and BMP target genes without altering Bmp6 and Bmp2 mRNA levels (Figure 1D). A previous study showed that peak Erfe expression was observed 4 hours after phlebotomy or EPO treatment, followed by a decrease in Id1 between 4 hours and 9 hours,8 consistent with our data.

EPO suppresses BMP target genes in an ERFE-dependent manner. (A-B) WT and Erfe KO male mice (10 to 13 weeks old) were injected with 3 doses of 200 IU EPO or vehicle (Veh) at 1 dose every 24 hours and were analyzed 24 hours after the last injection to measure expression of BMP-target genes in the liver (A) and serum and liver iron (Fe) (B). (C-D) Nine-week-old WT male mice were injected intravenously with 200 µg of murine Erfe or a clipped (inactive) version of the protein as a control (Ctrl). Mice were analyzed 3 hours after the injections to measure serum and liver iron (C) and expression of BMP-target genes, Bmp2 and Bmp6 in the liver (D). Bars represent mean ± standard deviation. Gene expression represented as −ΔCT, calculated as the threshold cycle (CT) for the gene of interest minus the reference gene (Hprt). Threshold set as 0.2. n = 6-8 mice per group. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey test for multiple comparisons (A-B) or Student t test (C-D).

EPO suppresses BMP target genes in an ERFE-dependent manner. (A-B) WT and Erfe KO male mice (10 to 13 weeks old) were injected with 3 doses of 200 IU EPO or vehicle (Veh) at 1 dose every 24 hours and were analyzed 24 hours after the last injection to measure expression of BMP-target genes in the liver (A) and serum and liver iron (Fe) (B). (C-D) Nine-week-old WT male mice were injected intravenously with 200 µg of murine Erfe or a clipped (inactive) version of the protein as a control (Ctrl). Mice were analyzed 3 hours after the injections to measure serum and liver iron (C) and expression of BMP-target genes, Bmp2 and Bmp6 in the liver (D). Bars represent mean ± standard deviation. Gene expression represented as −ΔCT, calculated as the threshold cycle (CT) for the gene of interest minus the reference gene (Hprt). Threshold set as 0.2. n = 6-8 mice per group. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey test for multiple comparisons (A-B) or Student t test (C-D).

Inhibition of hepcidin by Erfe requires BMP signaling but not TMPRSS6

Microarray and RNA sequencing analysis of human hepatoma cells treated with Erfe for 24 hours revealed suppression of several BMP/SMAD target genes (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2), 4 of which were detected in both assays (ID1, ID2, SMAD6, and HAMP; confirmed by qRT-PCR) (Figure 2B). The decreased expression of SMAD6 in vitro and SMAD7 in vivo (Figure 1A) indicate that suppression of BMP target genes by Erfe is not caused by upregulation of inhibitory SMADs. A recent study reported that conditional ablation of Smad1 and Smad5 in hepatocytes does not further suppress Hamp after EPO injection, suggesting that BMP/SMAD signaling is required for ERFE activity.16 We found that Erfe in combination with LDN-193189 (a potent inhibitor of BMP signaling17 ) did not further suppress HAMP or ID1 compared with LDN-193189 alone at baseline or upon HAMP stimulation by interleukin-6 (supplemental Figure 3A), consistent with a requirement for intact BMP signaling for Erfe function. There are conflicting data regarding the involvement of matriptase-2 in Erfe-mediated HAMP suppression.18,19 We found that after silencing TMPRSS6 in Huh7 cells, Erfe still suppressed HAMP to the same levels as WT, suggesting that matriptase-2 is not required for HAMP suppression by Erfe (supplemental Figure 3B).

ERFE suppresses BMP/SMAD signaling by inhibiting BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. (A) Venn diagram representing the number of genes differentially expressed by Huh7 cells treated with murine Erfe (10 µg/mL) compared with vehicle-treated cells and analyzed by Illumina microarray or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). (B) Gene expression measured by qRT-PCR of the common 4 differentially expressed genes in Huh7 cells treated with vehicle or murine Erfe (10 µg/mL). (C) Huh7 cells treated with mouse ERFE (10 µg/mL), BMP6 (6 nM or 18 nM), and LDN (100 nM), alone or in combination, for 30 minutes. pSMAD1/5/8 and SMAD1 were analyzed by western blot. pSMAD:SMAD ratios were calculated by densitometry. (D) C2C12 BRE-Luc cells were treated with 2 nM BMP in combination with a gradient of mouse ERFE concentrations (7.5 pM to 0.5 µM) for 24 hours, and luminescence was measured in each well. Data were normalized to percentage of maximum luminescence (no ERFE). (E) Huh7 cells treated with 2 nM BMPs alone or in combination with 10 µg/mL of mouse ERFE in serum-free media and analyzed 6 hours after treatment for HAMP gene expression by qRT-PCR. (F) Homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assay for detection of binding between ERFE and BMP, using cryptate-labeled anti-ERFE antibody and BMPs (0.1-200 nM) and unlabeled antibody as positive control. Values were calculated as %ΔF = [(F665 sample/F615 sample) − (F665 control/F615 control) (F665 control/F615 control)] × 100, in which control is the background fluorescence energy transfer in wells containing labeled antibody alone. Results for panels B-F represent mean ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 by Student t test. RLU, relative light units.

ERFE suppresses BMP/SMAD signaling by inhibiting BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. (A) Venn diagram representing the number of genes differentially expressed by Huh7 cells treated with murine Erfe (10 µg/mL) compared with vehicle-treated cells and analyzed by Illumina microarray or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). (B) Gene expression measured by qRT-PCR of the common 4 differentially expressed genes in Huh7 cells treated with vehicle or murine Erfe (10 µg/mL). (C) Huh7 cells treated with mouse ERFE (10 µg/mL), BMP6 (6 nM or 18 nM), and LDN (100 nM), alone or in combination, for 30 minutes. pSMAD1/5/8 and SMAD1 were analyzed by western blot. pSMAD:SMAD ratios were calculated by densitometry. (D) C2C12 BRE-Luc cells were treated with 2 nM BMP in combination with a gradient of mouse ERFE concentrations (7.5 pM to 0.5 µM) for 24 hours, and luminescence was measured in each well. Data were normalized to percentage of maximum luminescence (no ERFE). (E) Huh7 cells treated with 2 nM BMPs alone or in combination with 10 µg/mL of mouse ERFE in serum-free media and analyzed 6 hours after treatment for HAMP gene expression by qRT-PCR. (F) Homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assay for detection of binding between ERFE and BMP, using cryptate-labeled anti-ERFE antibody and BMPs (0.1-200 nM) and unlabeled antibody as positive control. Values were calculated as %ΔF = [(F665 sample/F615 sample) − (F665 control/F615 control) (F665 control/F615 control)] × 100, in which control is the background fluorescence energy transfer in wells containing labeled antibody alone. Results for panels B-F represent mean ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 by Student t test. RLU, relative light units.

Erfe inhibits hepcidin induction by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7

Erfe caused a decrease in SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8 phosphorylation relative to cells not treated with Erfe (Figure 2C), both at baseline and after BMP6 stimulation. Because HAMP can be stimulated by a variety of ligands,11 we tested the effect of Erfe on cells treated with various BMPs using C2C12 BRE-Luc cells. Increased concentrations of Erfe dose-dependently decreased activation of BMP signaling by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7 (50% inhibitory concentration: 15 nM, 25 nM, and 22 nM, respectively) but had no effect on BRE-Luc activity stimulated by BMP2, BMP4, and BMP9 (Figure 2D). Similarly, using hepatoma cells, Erfe strongly suppressed endogenous HAMP and ID1 induction by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7, with no or minor effects on BMP2, BMP4, BMP9, or activin B (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 4). Next, by immunizing Erfe KO mice with recombinant ERFE, we generated an anti-ERFE monoclonal antibody that neutralized the ability of Erfe to inhibit hepcidin induction by BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7 but did not influence the hepcidin-stimulating activity of the BMPs in the absence of Erfe (supplemental Figure 5). Using this antibody and recombinant BMPs, we then performed homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence competition assays (supplemental Figure 6). Unlabeled anti-ERFE efficiently competed with labeled anti-ERFE to bind Erfe as expected. BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7 (but not BMP4) dose dependently prevented the labeled anti-ERFE from binding Erfe, suggesting that the neutralizing antibody functions by disrupting the ability of Erfe to bind these BMPs (Figure 2F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Erfe preferentially binds and inhibits members of the BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7 subgroup of BMPs, leading to decreased hepcidin expression. In mice, BMP2 and BMP6 are both required for appropriate hepcidin expression.12,20 The relative inability to inhibit BMP2 indicates that ERFE may not fully suppress hepcidin. Our findings have important consequences for understanding hepcidin regulation by erythropoiesis and for potential therapies aimed at manipulating hepcidin expression.

This online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elizabeth DiBlasio Smith and Chris Corcoran for contributions to protein purification; Darren Ferguson, Caryl Meade, and Ashley Schwab for contributions to antibody production; Jonathon Merrill, Jordan Tanner, and Roo Bhasin for contributions to the techniques involving mice; and Joe Frost and Pei-Jin Lim for scientific discussion.

This work was funded by a Pfizer-sponsored Rare Disease Consortium Award, and the Medical Research Council United Kingdom (MRC Human Immunology Unit core funding) (H.D.). S.J.D. is a Jenner Investigator, a Lister Institute Research Prize Fellow, and a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow (106917/Z/15/Z).

Authorship

Contribution: J.A., N.F., K.M., A.E.A., S.-R.P., O.C., M.L., S.J.D., R.J., and H.D. designed the research; J.A., N.F., K.M., A.S., D.Q., V.T., A.B., M.T., E.R.L., A.E.A., and S.-R.P. performed the research; J.A., N.F., K.M., A.S., V.T., A.E.A., and S.-R.P. collected data; J.A., N.F., K.M., A.S., V.T., S.T., A.E.A., S.-R.P., O.C., M.L., S.J.D., R.J., and H.D. analyzed and interpreted data; J.A., A.S., and S.T., performed statistical analysis; and J.A., N.F., K.M., S.J.D., R.J., and H.D. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.A., K.M., D.Q., S.J.D., and H.D. received funding from Pfizer. N.F., A.S., V.T., A.B., M.T., E.R.L., O.C., M.L., and R.J. are Pfizer employees. N.F., O.C., R.J., J.A., K.M., S.J.D., and H.D. are named inventors on a patent application currently under evaluation. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hal Drakesmith, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headley Way, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom: e-mail: alexander.drakesmith@imm.ox.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

Author notes

N.F. and K.M. contributed equally to this work.

S.J.D., R.J., and H.D. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 2. ERFE suppresses BMP/SMAD signaling by inhibiting BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. (A) Venn diagram representing the number of genes differentially expressed by Huh7 cells treated with murine Erfe (10 µg/mL) compared with vehicle-treated cells and analyzed by Illumina microarray or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). (B) Gene expression measured by qRT-PCR of the common 4 differentially expressed genes in Huh7 cells treated with vehicle or murine Erfe (10 µg/mL). (C) Huh7 cells treated with mouse ERFE (10 µg/mL), BMP6 (6 nM or 18 nM), and LDN (100 nM), alone or in combination, for 30 minutes. pSMAD1/5/8 and SMAD1 were analyzed by western blot. pSMAD:SMAD ratios were calculated by densitometry. (D) C2C12 BRE-Luc cells were treated with 2 nM BMP in combination with a gradient of mouse ERFE concentrations (7.5 pM to 0.5 µM) for 24 hours, and luminescence was measured in each well. Data were normalized to percentage of maximum luminescence (no ERFE). (E) Huh7 cells treated with 2 nM BMPs alone or in combination with 10 µg/mL of mouse ERFE in serum-free media and analyzed 6 hours after treatment for HAMP gene expression by qRT-PCR. (F) Homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assay for detection of binding between ERFE and BMP, using cryptate-labeled anti-ERFE antibody and BMPs (0.1-200 nM) and unlabeled antibody as positive control. Values were calculated as %ΔF = [(F665 sample/F615 sample) − (F665 control/F615 control) (F665 control/F615 control)] × 100, in which control is the background fluorescence energy transfer in wells containing labeled antibody alone. Results for panels B-F represent mean ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 by Student t test. RLU, relative light units.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/132/14/10.1182_blood-2018-06-857995/4/m_blood857995f2.png?Expires=1767711137&Signature=IkLlwMWJ9d8NxoGfBWQsGjiC7-horA~oFRwfNg2cLSm6x02bfEsYCOi1wdUfvwge~pow9Yr69U3xWjI1C1vB672u6XUglsS72h1YTOQKE5KLbnp1vDs2-1y2aCErTuWi78~zGqxccCM~GMKFnq6-4WRQOu1sisVGQHytmPTYjEbaQ-8w4SFR5gdOqWfK2RC-ZQhzSGR8QjZFL~eAfQcRbr-GlFghShnit5JgxQVlEMGHP4A68lx5yxix2i8YR0r0vP8Jl2-L9tmFoBaeX57JuNVGTGsmRma2C49QKBCDFTC~1fGHjhXz4-nX6cP9hZprzMOIo9dVHVkYJYeVipGkgQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal