In this issue of Blood, O’Brien et al report long-term efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in the first cohort of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated, now with 5-year follow-up, the longest of any CLL cohort to date.1

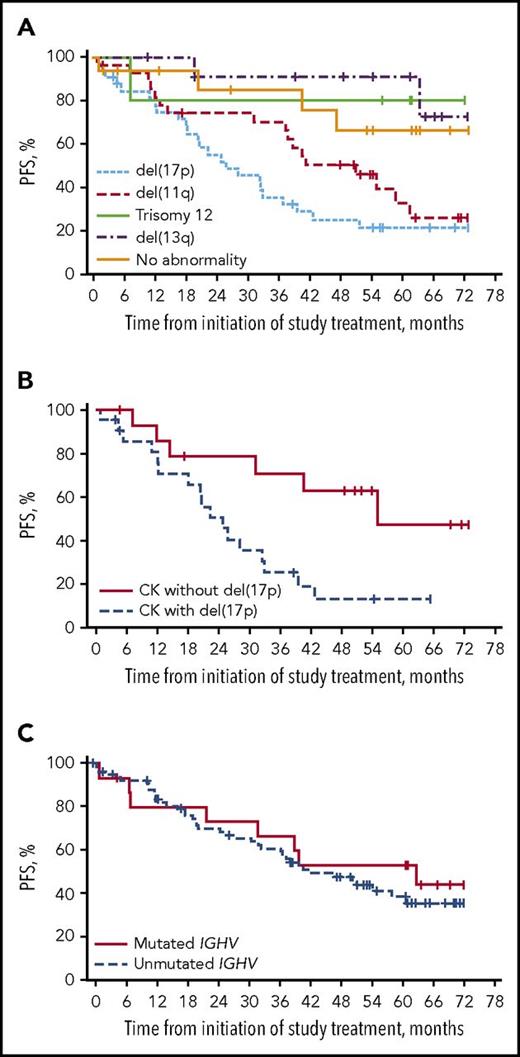

PFS with ibrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL by chromosomal abnormalities detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (A), by presence or absence of del(17p) among those with complex karyotype (CK) (B), and by IGHV mutational status (C). See complete Figures 3, 4, and 6 in the article by O’Brien et al that begins on page 1910.

PFS with ibrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL by chromosomal abnormalities detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (A), by presence or absence of del(17p) among those with complex karyotype (CK) (B), and by IGHV mutational status (C). See complete Figures 3, 4, and 6 in the article by O’Brien et al that begins on page 1910.

Ibrutinib has come into widespread use since its initial US Food and Drug Administration approval for relapsed CLL 4 years ago, based on the early results of this same study.2 Although many other studies have confirmed the high efficacy of ibrutinib in CLL, follow-up has remained quite short. Thus, many questions about durability and predictors of response, as well as long-term tolerability, have remained unanswered. In this study of high-risk patients with relapsed/refractory disease, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was reached at a strikingly good 51 months, which compares favorably to that achieved with older regimens in a comparable patient population.3 The median treatment duration for the relapsed/refractory cohort was 39 months, with 33% discontinuing for disease progression. Interestingly, the PFS curves by cytogenetic abnormality have a distribution similar to that of the classic survival curves of Döhner et al4 (see figure panel A), with del(17p) remaining highest risk, with a median PFS of 26 months. Complex karyotype has emerged as a predictor of shortened PFS in ibrutinib studies,5 and in this study, it was associated with a 31-month PFS, driven significantly by cooccurrence with del(17p) (see figure panel B). The extent to which the adverse prognosis of complex karyotype is driven by its association with del(17p) remains unknown, but clearly, this needs to be investigated prospectively in future ibrutinib studies.

Overall, these findings seem aligned with the recently reported 59% 3-year PFS achieved with ibrutinib in the confirmatory RESONATE trial,6 which randomly assigned patients with relapsed CLL to ibrutinib or ofatumumab. In the study by O’Brien et al, significant predictors of both PFS and overall survival in multivariate analysis included del(17p) and number of prior therapies. Similarly, in RESONATE, biallelic inactivation of TP53 [including del(17p)] and >2 prior therapies were associated with shorter PFS.6,7 Recent reports from RESONATE and other ibrutinib studies have suggested that ibrutinib may overcome the negative impact of other traditionally high-risk prognostic factors, such as del(11q) or unmutated IGHV.8 With no difference seen at 2- to 3-year follow-up, these reports establish the efficacy of ibrutinib in these prognostic subgroups, but they raise the question of whether long follow-up will be required to truly assess differences. With the 5-year follow-up of O’Brien et al, we see perhaps a hint that these factors may still have adverse impacts, at least in some contexts. For example, the duration of response for del(11q) CLL was reduced at 39 months, with a median PFS of 51 months (see figure panel A). More patients with unmutated IGHV discontinued therapy, with disease progression the most common reason, although PFS was not different at present (see figure panel C). Ultimately, the data remain relatively immature among subgroups in which few progression events have occurred, underscoring both the effectiveness of ibrutinib and the length of follow-up required for a comprehensive understanding of its effect within subgroups.

The other notable result of this study is the long follow-up of adverse events (AEs) among these patients intended to remain on continuous ibrutinib therapy. Approximately 20% of treatment discontinuations in both the treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory cohorts were attributed to AEs over 5-year follow-up, which compares favorably to the 42% discontinuation rate at a median of 17 months in a recent real-world report of ibrutinib use.9 It is notable, however, that 30% of patients in this study developed grade ≥3 hypertension, and ∼10% each had major hemorrhage and atrial fibrillation. Pneumonia of grade ≥3 also seems constant across the 5-year treatment interval. Prior work has suggested a particular susceptibility to invasive fungal infections among ibrutinib-treated patients, and this issue of Blood also contains a report from Ghez et al10 (with commentary) on 33 patients who developed invasive fungal infections during ibrutinib treatment. This updated AE profile may start to close the gap between clinical trials and the higher rates of toxicity reported in recent real-world reports of ibrutinib use9 and underscores the need for ongoing vigilance throughout ibrutinib therapy.

In the context of this more mature AE profile, it is notable that 45% of the small low-risk treatment-naïve cohort in this study has now discontinued ibrutinib, many apparently after year 4, because only 23% were treated for <4 years. The reasons for this are not fully explained, with 19% attributed to AEs and 6% to disease progression, leaving 20% of unclear etiology, potentially related to low-grade AEs. The observation that the median duration of ibrutinib therapy in this frontline lower-risk cohort was only ∼5.5 years is potentially quite useful in counseling patients, if these results in this admittedly small cohort are confirmed. The relatively late timing of discontinuation in this study suggests that longer follow-up of RESONATE-2, which randomly assigned untreated older patients with CLL to ibrutinib or chlorambucil, could have similar findings; at current 24-month follow-up, 79% of patients remain on ibrutinib.11 Disease outcomes in this small frontline low-risk cohort are not surprisingly excellent, even at 5 years. However, the key unanswered question, with almost no data, concerns the durability of remission after stopping ibrutinib in a deep but probably not complete remission, as compared with continuing ibrutinib. This durability may ultimately differ based on depth of response, duration of therapy, and CLL prognostic factors, but as yet, it remains unknown. Further follow-up of patients who discontinue without disease progression, as well as systematic investigation of time-limited therapy, including novel likely combination approaches, is clearly warranted given this long-term toxicity and discontinuation data, with the goal of maximizing ibrutinib benefit while minimizing toxicity.

With this 5-year update of single-agent ibrutinib therapy, we have reached a median PFS in patients with relapsed/refractory disease, as well as a median duration on therapy in previously untreated older patients. Both represent a significant step forward in our knowledge of the natural history of ibrutinib therapy, but many questions remain for the future: mature follow-up of larger trials, outcomes in high-risk and/or young patients treated frontline, and outcomes of time-limited or combination therapy, among others. Ibrutinib data are starting to mature, but much opportunity for growth remains.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R.B. has served as a consultant for Janssen, Pharmacyclics, AstraZeneca, Sun, Redx, Sunesis, Loxo, Gilead, TG Therapeutics, Verastem, and AbbVie and receives research funding from Sun and Gilead.