Key Points

SETD1A regulates DNA damage signaling and repair in HSCs and hematopoietic precursors in the absence of reactive oxygen species accumulation.

SETD1A is important for the survival of mice after inflammation-induced HSC activation in situ.

Abstract

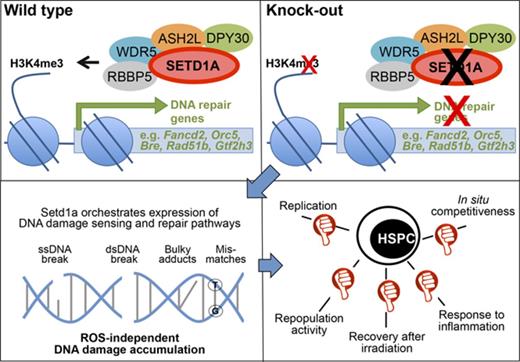

The regenerative capacity of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is limited by the accumulation of DNA damage. Conditional mutagenesis of the histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferase, Setd1a, revealed that it is required for the expression of DNA damage recognition and repair pathways in HSCs. Specific deletion of Setd1a in adult long-term (LT) HSCs is compatible with adult life and has little effect on the maintenance of phenotypic LT-HSCs in the bone marrow. However, SETD1A-deficient LT-HSCs lose their transcriptional cellular identity, accompanied by loss of their proliferative capacity and stem cell function under replicative stress in situ and after transplantation. In response to inflammatory stimulation, SETD1A protects HSCs and progenitors from activation-induced attrition in vivo. The comprehensive regulation of DNA damage responses by SETD1A in HSCs is clearly distinct from the key roles played by other epigenetic regulators, including the major leukemogenic H3K4 methyltransferase MLL1, or MLL5, indicating that HSC identity and function is supported by cooperative specificities within an epigenetic framework.

Introduction

Lifelong maintenance of the immune system depends on self-renewing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that are activated under stress conditions such as infection to replenish blood cells during demand-adapted hematopoiesis.1 The accumulation of DNA damage limits the regeneration of blood cells and is a hallmark of aging and age-associated disorders, including blood cancers.2,3 The activation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) through interferon signaling during inflammation4 provides a physiological source for DNA damage, and lack of a functional Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway results in the attrition of activated HSCs in situ.5 It remains unknown whether other DNA damage repair pathways are involved in this process. The fundamental dilemma between the maintenance of genomic integrity and the need to replenish tissue through replication is now a central issue in stem cell research,6,7 highlighted by the counterintuitive finding that long-term (LT) HSCs are normally quiescent and thereby maintain genomic integrity by not replicating.8,9 In this context, information on the molecular nature of physiological regulators orchestrating the expression of components maintaining genomic integrity of dividing LT-HSCs and hematopoietic precursors (HPCs) is missing.

The first indication that epigenetic mechanisms contribute to the regulation of hematopoiesis was provoked by the realization that the major leukemia gene, mixed-lineage leukemia (Mll110 ), encodes a histone 3 lysine 4 methyltransferase11 of the Set1/Trithorax type.12 Knockout studies in mice revealed that Mll1 is required for definitive hematopoiesis and that embryos lacking MLL1 die at E13.5.13,14 MLL1 is 1 of 6 Set1/Trithorax-type histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferases (Mll1-4; Setd1a and -b) in mammals. Gathering evidence indicates that the other 5 are also involved in hematopoiesis and various leukemic transformations.15 However, a unifying understanding of how the 6 H3K4 methyltransferases relate to each other and regulate hematopoiesis remains elusive.

A comprehensive evaluation of epigenetic regulation in hematopoiesis, in particular the H3K4 methyltransferase system, using constitutive and conditional knockouts in the mouse, is emerging. Conditional ubiquitous depletion in adults of MLL1 (Kmt2a16 ) or SETD1A (Kmt2f17 ), but not MLL2 (Kmt2b18 ) or MLL4 (Kmt2d19 ), is lethal. In hematopoiesis, lack of MLL1 or MLL4 resulted in loss of HSC maintenance in G0 and in impaired or complete absence of repopulation activity after transplantation, which is a test that imposes replication stress through the requirement for extensive proliferation. The other 2 of the 6, Setd1b (Kmt2g) and Mll3 (Kmt2c), have not yet been functionally examined by conditional mutagenesis. However, 2 common subunits of H3K4 methyltransferase complexes (Dpy30, Cfp1) have been investigated, and recent conditional mutagenesis of either complex member revealed an essential role in adult hematopoiesis.20,21 In both cases, loss of function in mice was lethal, most likely because of the ablation-induced stark pancytopenia. It remains unknown as to which defective H3K4 methylation complex caused the phenotype or whether the severe defects were due to summated effects from dysfunction of more than one H3K4 methylation complex.

SETD1A is identified as the major H3K4 methyltransferase in mouse embryonic stem cells, and knockout embryos die shortly before gastrulation.22 Conditional ablation of Setd1a in hematopoietic cells revealed that it is a regulator of B-cell differentiation in the bone marrow (BM) and spleen,17 with an impact on erythrocyte differentiation,23 suggesting that SETD1A regulates adult hematopoiesis. However, a systematic analysis of SETD1A in HSCs and progenitors has been lacking, and a clear functional assignment has not been made. Here we used various Cre drivers and assays to dissect SETD1A function in vivo and in vitro. Thereby we defined critical functions of SETD1A in HSCs and committed progenitors.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J (B6) and B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (B6.SJL) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Setd1aF/F mice were described previously22 and crossed with Rosa26-CreERT2 (R.26-CreERT2 24 ), SCL-CreERT,25 Vav-Cre,26 and CD4-Cre27 mice. LT-HSC in vivo proliferation was analyzed using SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F;R.26-rtTAki/ki;Col1a1-tetO-H2B-mCherryki/ki 28 mice. Details on tamoxifen, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), doxycyclin, and poly I:C (pI:C) treatment, irradiation, and transplantation are provided in the supplemental Material and methods, available on the Blood Web site. Flow cytometry was performed, as has been previously described.29

Culture

Colony assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Methocult M3434; StemCell Technologies). For single-cell cultures, LT-HSCs (KSL = lineage, Lin− [CD3, CD11b, CD19, B220, Gr1, NK1.1, Ter119]− Kit+, Sca-1+; CD34− CD135−), short-term (ST) HSCs (KSL CD34+ CD135−), and multipotent progenitors (MPPs; KSL CD34+ CD135+) were sorter purified. For bulk analysis, 3000 KSL or myeloid progenitors (MPs; Lin− Kit+ Sca-1−) or 600 LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs were cultivated for 3 or 8 days, respectively.

Molecular analysis

Molecular analysis, including next-generation sequencing,30 quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), recombination analysis, and alkaline comet assays (OxiSelect, Cell Biolabs, Inc.), was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. H3K4 methylation was tested by Western blot (Lin− cells) and immunofluorescence (KSL cells). Details for all procedures are given in the supplemental Material and methods.

Statistics

Significant differences of survival were determined using the log-rank test (Prism 5). Two-tailed Student t tests were performed for all other analyses (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001). Error bars show standard deviations.

Results

Conditional deletion of Setd1a in adult mice is lethal

The histone lysine methyltransferase Setd1a is expressed in mouse HSPCs (Figure 1A-B). Complete loss of Setd1a in the embryo using either a targeted gene trap allele or an allele lacking exon 4 provoked lethality shortly after implantation.22 To examine SETD1A function in adult mice, we bypassed embryonic lethality using tamoxifen (TAM)–inducible site-specific recombination,31 initially from the Rosa26 locus.24,32 In 2-month-old adults, deletion of Setd1a exon 4 led to the death of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F mice 12 to 26 days after TAM induction (Figure 1C). Because of the near-ubiquitous expression of CreERT2 in these mice, it was not clear in which cell types SETD1A was required, but the speed of death suggested that defects in hematopoiesis could be involved. This idea was tested using Vav-Cre to delete Setd1a, which resulted in lethality 7 to 20 days after birth (Figure 1D). Vav-Cre-mediated cell type–specific deletion of Setd1a results in the lack of expression of SETD1A in definitive HSCs from the time point of their emergence during embryonic development.26 Vav-Cre+;Setd1aF/F mice were born at normal Mendelian frequencies (supplemental Figure 1A-C) but lacked Lin− Kit+ Sca-1+ (Lin = CD3, CD11b, CD19, B220, Gr1, NK1.1, Ter119) HSPCs in the BM 9 days after birth (supplemental Figure 1D-E), indicating that these cells are not generated or expanded during pre- and neonatal development in the absence of SETD1A. To confirm this indication, TAM induction of transplanted R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F BM chimeric mice (scheme; Figure 1E) resulted in pancytopenia characterized by a severe drop of hematological blood parameters. After the mice had recovered from the impact of tamoxifen, red and white blood cells were reduced in comparison with the transplanted control (R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1a+/+) chimeras (Figure 1F). Furthermore, SETD1A-deficient HSPCs exhibited reduced capacity to form colonies in vitro (Figure 1G). In Lin− cells, lack of SETD1A led to global reductions in mono-, di-, and trimethylation on lysine 4 of histone 3 (H3K4me1, me2, me3; Figure 1H). Taken together, the data indicate that SETD1A is an important cell-intrinsic regulator for adult HSC differentiation and is the major H3K4 methyltransferase in blood stem and progenitor cells.

Setd1a expression in postnatal hematopoietic cells is crucial for survival. (A) Normalized RNA-sequence counts for Mll1, Mll2, Mll3, Mll4, Setd1a, and Setd1b in KSL Slam LT-HSCs (lineage− = Lin−, Kit+ Sca-1+ [KSL] CD48/41− CD150+ CD34− CD135−). Shown is the average of 3 replicates of 1 experiment. (B) qPCR of Setd1a transcripts in LT-HSCs (KSL CD34− CD135−), ST-HSCs (KSL CD34+ CD135−), MPPs (KSL CD34+ CD135+), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; Lin− Kit+ Sca-1− [MP] CD34+ CD16/32−), megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors (MEPs; MP CD34− CD16/32−), and granulocyte macrophage progenitors (GMPs; MP CD34+ CD16/32+) from wild-type mice. Setd1a transcript expression is shown in relation to transcripts of Rpl19. (C) Survival curve of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red line; n = 7) and control mice (blue line; n = 15) after tamoxifen induction. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (D) Survival curve of Vav-Cre+;Setd1aF/F (red line; n = 17) and control (blue line; n = 15) mice. (E) Experimental outline using R.26-CreERT2+ deleter mice. (F) White and red blood cell counts, hematocrit, hemoglobin, and platelet values from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines; n = 10) or R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1a+/+ (blue lines; n = 10) chimeric mice before (0 day) and after TAM treatment or untreated wild-type (gray lines; n = 3) controls. (G) Plot shows colony growth 8 days (BFU-E) and 12 days (G, M, GM, and GEMM) after culture of 104 BM cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice (n = 6) that were TAM induced 8 days beforehand. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (H) Western blot of H3K4me1, H3K4me2, and H3K4me3 in Lin− cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice after 4 days in vivo and 2 days in vitro TAM induction (n = 3 each). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (I) Representative fluorescence-activated cell scan (FACS) plots resolve thymocytes from CD4-Cre+;Setd1aF/F and control mice for the expression of CD4 and CD8. Plots are gated on 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) negative cells. (J) Quantification of CD4 and CD8 single positive thymocytes. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; ns, not significant; Plt, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; SP, single positive; WBC, white blood cell.

Setd1a expression in postnatal hematopoietic cells is crucial for survival. (A) Normalized RNA-sequence counts for Mll1, Mll2, Mll3, Mll4, Setd1a, and Setd1b in KSL Slam LT-HSCs (lineage− = Lin−, Kit+ Sca-1+ [KSL] CD48/41− CD150+ CD34− CD135−). Shown is the average of 3 replicates of 1 experiment. (B) qPCR of Setd1a transcripts in LT-HSCs (KSL CD34− CD135−), ST-HSCs (KSL CD34+ CD135−), MPPs (KSL CD34+ CD135+), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; Lin− Kit+ Sca-1− [MP] CD34+ CD16/32−), megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors (MEPs; MP CD34− CD16/32−), and granulocyte macrophage progenitors (GMPs; MP CD34+ CD16/32+) from wild-type mice. Setd1a transcript expression is shown in relation to transcripts of Rpl19. (C) Survival curve of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red line; n = 7) and control mice (blue line; n = 15) after tamoxifen induction. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (D) Survival curve of Vav-Cre+;Setd1aF/F (red line; n = 17) and control (blue line; n = 15) mice. (E) Experimental outline using R.26-CreERT2+ deleter mice. (F) White and red blood cell counts, hematocrit, hemoglobin, and platelet values from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines; n = 10) or R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1a+/+ (blue lines; n = 10) chimeric mice before (0 day) and after TAM treatment or untreated wild-type (gray lines; n = 3) controls. (G) Plot shows colony growth 8 days (BFU-E) and 12 days (G, M, GM, and GEMM) after culture of 104 BM cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice (n = 6) that were TAM induced 8 days beforehand. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (H) Western blot of H3K4me1, H3K4me2, and H3K4me3 in Lin− cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice after 4 days in vivo and 2 days in vitro TAM induction (n = 3 each). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (I) Representative fluorescence-activated cell scan (FACS) plots resolve thymocytes from CD4-Cre+;Setd1aF/F and control mice for the expression of CD4 and CD8. Plots are gated on 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) negative cells. (J) Quantification of CD4 and CD8 single positive thymocytes. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; ns, not significant; Plt, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; SP, single positive; WBC, white blood cell.

Notably, using CD4-Cre, we found that SETD1A is not required in thymocytes (Figure 1I-J), despite efficient recombination (supplemental Figure 1F), thereby indicating that SETD1A is required earlier in hematopoiesis. This observation also provides further evidence that SETD1A is not essential in all cell types.22

Persistence of Setd1a-deficient LT-HSCs and progenitors

Mixed BM chimeras were established between R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and wild-type donor cells. Three months after transplantation, recombination of the Setd1aF/F alleles was induced by TAM treatment. Survival of the mice was ensured by wild-type competitor cells (scheme; Figure 2A). Consistent with the pancytopenia in plain BM chimeric mice (Figure 1F), the contribution of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F donor cells to blood neutrophils (PMN), other myeloid cells, and T and B lymphocytes severely declined after TAM treatment of competitively transplanted chimeric mice (Figure 2B). In contrast, LT-HSC numbers were unaffected (Figure 2C-D). The KSL compartment was enlarged (Figure 2E) owing to mild expansions of ST-HSCs and MPPs upon deletion of SETD1A (Figure 2D). However, more downstream HPCs, including CMPs and MEPs, were diminished (Figure 2D). The strong effect on MEPs is consistent with a recent report on the role of SETD1A in red blood cell differentiation.23 Efficient recombination of the loxP-flanked Setd1a allele in LT-HSCs was confirmed by PCR genotyping of 165 single LT-HSCs (Figure 2F), indicating that LT-HSCs can survive without SETD1A, which is, however, required for later steps of hematopoietic differentiation.

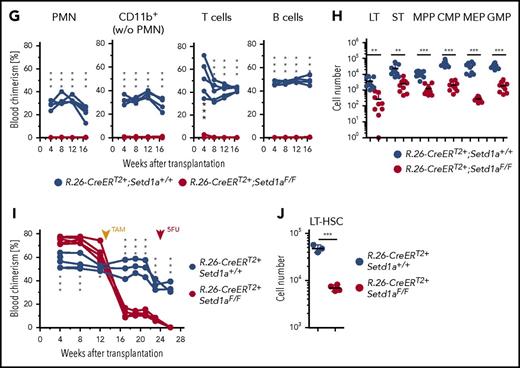

Setd1a-deficient HSCs survive in situ but cannot contribute to hematopoiesis after transplantation. (A) Experimental outline for competitive transplantations using R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or Setd1a+/+ Lin− BM donor cells together with wild-type Lin− BM cells (1:1). TAM was induced 3 months after transplantation; the mice were bled regularly and analyzed 2.5 months later. Data for primary transplantation are representative of 4 independent experiments. A total of 107 BM cells from primary recipients were transplanted into secondary recipients; blood chimerism was determined over 16 weeks, and BM chimerism analyzed after 16 weeks. Data for secondary transplantations are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Test or control donor cell chimerism in blood neutrophils (PMNs), CD11b+ Gr1−/lo monocytes and eosinophils, and T and B lymphocytes before and after TAM treatment of BM chimeras. (C) Dot plots show the expression of Kit and Sca-1 on Lin− donor BM cells that were further resolved for the expression of CD34 and CD135 from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control BM chimeras that have received TAM 3 months after transplantation and were analyzed 2.5 months later. (D) Cell number of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control donor LT-HSCs (LT), ST-HSCs (ST), MPPs, CMPs, MEPs, and GMPs from 4 independent experiments. (E) Frequency of KSL in Lin− donor cells as shown in panel C. Data from 4 independent experiments are shown. (F) Single-cell PCRs specific for Setd1aF, Setd1a+, or Setd1adel alleles in donor-derived KSL Slam LT-HSCs from BM chimeras. A total of 165 cells from 2 independent mice were analyzed (39 and 126 cells), and representative PCR results from 16 of them are shown here. (G) R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines) or control (blue lines) donor cell contributions to blood neutrophils, myeloid, T, and B cells in secondary recipient mice. At the time point of transplantation, LT-HSC numbers were comparable between R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and wild-type control BM chimeric primary recipients (Figure 2D). (H) R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red circles) or control (blue circles) LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, MPPs, CMPs, MEPs, and GMPs in the BM of secondary recipients. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (I) R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines) or control (blue lines) mixed BM chimeras were injected with 5-FU 10 weeks after TAM treatment, and PMN blood chimerism was determined 2 weeks later. (J) LT-HSC numbers of donor R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red circles) or R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1a+/+ (blue circles) in 5-FU-treated BM chimeras as described in panel I. w/o, without; wt, wild-type.

Setd1a-deficient HSCs survive in situ but cannot contribute to hematopoiesis after transplantation. (A) Experimental outline for competitive transplantations using R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or Setd1a+/+ Lin− BM donor cells together with wild-type Lin− BM cells (1:1). TAM was induced 3 months after transplantation; the mice were bled regularly and analyzed 2.5 months later. Data for primary transplantation are representative of 4 independent experiments. A total of 107 BM cells from primary recipients were transplanted into secondary recipients; blood chimerism was determined over 16 weeks, and BM chimerism analyzed after 16 weeks. Data for secondary transplantations are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Test or control donor cell chimerism in blood neutrophils (PMNs), CD11b+ Gr1−/lo monocytes and eosinophils, and T and B lymphocytes before and after TAM treatment of BM chimeras. (C) Dot plots show the expression of Kit and Sca-1 on Lin− donor BM cells that were further resolved for the expression of CD34 and CD135 from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control BM chimeras that have received TAM 3 months after transplantation and were analyzed 2.5 months later. (D) Cell number of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control donor LT-HSCs (LT), ST-HSCs (ST), MPPs, CMPs, MEPs, and GMPs from 4 independent experiments. (E) Frequency of KSL in Lin− donor cells as shown in panel C. Data from 4 independent experiments are shown. (F) Single-cell PCRs specific for Setd1aF, Setd1a+, or Setd1adel alleles in donor-derived KSL Slam LT-HSCs from BM chimeras. A total of 165 cells from 2 independent mice were analyzed (39 and 126 cells), and representative PCR results from 16 of them are shown here. (G) R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines) or control (blue lines) donor cell contributions to blood neutrophils, myeloid, T, and B cells in secondary recipient mice. At the time point of transplantation, LT-HSC numbers were comparable between R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and wild-type control BM chimeric primary recipients (Figure 2D). (H) R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red circles) or control (blue circles) LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, MPPs, CMPs, MEPs, and GMPs in the BM of secondary recipients. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (I) R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines) or control (blue lines) mixed BM chimeras were injected with 5-FU 10 weeks after TAM treatment, and PMN blood chimerism was determined 2 weeks later. (J) LT-HSC numbers of donor R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red circles) or R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1a+/+ (blue circles) in 5-FU-treated BM chimeras as described in panel I. w/o, without; wt, wild-type.

SETD1A-deficient HSCs failed to contribute to stress-induced hematopoiesis

Because a function for SETD1A in adult LT-HSCs was not revealed by the above investigations, LT-HSCs lacking SETD1A were challenged under conditions of replicative stress. Transplantation of BM cells from TAM-induced primary mixed BM chimeras into secondary recipients (scheme; Figure 2A) revealed no detectable contribution of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F donor cells to myeloid or lymphoid blood compartments (Figure 2G). Importantly, however, low levels of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs were found (Figure 2H), suggesting that SETD1A contributes to HSPC expansion.

A further stress condition was examined by injecting 5-FU into TAM-treated BM chimeric mice. The injection abolished the contribution of Setd1a-deleted cells to blood neutrophils, whereas controls recovered from the 5-FU assault (Figure 2I). Additionally, R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F HSCs were severely decreased 14 days after 5-FU administration (Figure 2J). We conclude that SETD1A is an important regulator of demand-adapted hematopoiesis. Although it is not strictly required for survival of stem and progenitor cells, it may contribute to their expansion.

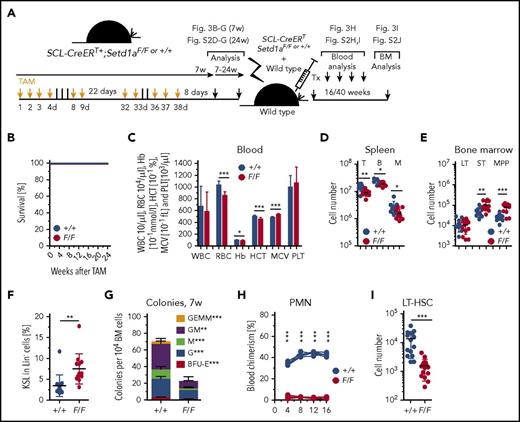

SETD1A-deficient LT-HSCs are functionally impaired

To investigate the effect of Setd1a deletion in LT-HSCs, we generated SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice (scheme; Figure 3A). In contrast to ubiquitous Setd1a deletion using R.26-CreERT2+, and deletion of Setd1a in definitive HSCs at the time point of their emergence during development (Vav-Cre), deletion mediated by SCL-CreERT is largely confined to LT-HSCs with little recombination activity in hematopoietic progenitors.25 The use of this Cre deleter delivered an important insight because the SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice survived for at least 24 weeks after TAM induction (Figure 3B). As was expected, the efficiency of SCL-CreERT recombination was high in LT-HSCs but lower in KSL, MP, and PMN cell fractions (supplemental Figure 2A), suggesting that hematopoietic activity of Setd1a wild-type progenitor cells suffices for survival.8,9 Also in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F HSPCs, mono-, di-, and trimethylation of H3K4 was significantly decreased in the absence of SETD1A (supplemental Figure 2B-C). Concordantly, only modest perturbations in blood erythrocytes (Figure 3C), spleen T, B, and myeloid cells (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 2D-G) were observed 7 or 24 weeks after TAM induction in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice. Despite efficient recombination, LT-HSC numbers in the BM were unaltered (Figure 3E), whereas the KSL population was expanded (Figure 3F) with increased ST-HSCs and MPP populations (Figure 3E). Notably, colony formation from BM was strongly reduced (Figure 3G), and competitive transplantation revealed no SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F contribution to blood neutrophils, other myeloid cells, or T or B lymphocytes (Figure 3H; supplemental Figure 2H-I). However, there was a small but detectable population of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F donor LT-HSCs cells in the BM of the recipient mice 16 to 40 weeks after transplantation (Figure 3I; supplemental Figure 2J), suggesting that homing into the BM occurs independently of the presence of SETD1A (supplemental Figure 2K). The data from the SCL-CreERT experiments therefore concord with and focus the conclusions from the R.26-CreERT2 competitive transplantation experiments. SETD1A is not essential in LT-HSCs but contributes when stress is applied. Furthermore, it also appears to be required during differentiation.

LT-HSC-specific depletion of Setd1a is dispensable for survival but critically important for HSC function after transplantation. (A) Experimental outline for TAM treatment of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control mice and competitive transplantations using Lin− BM cells. (B) Survival of TAM-treated SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control mice (n = 6 each). (C) Blood parameters in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice 7 weeks after TAM treatment. Data are pooled from 5 (n = 16) independent experiments. (D) CD3+ T cells, B220+ B cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells in the spleen of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control animals that have received TAM treatment 7 weeks before. (E) Numbers of LT- HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control mice that have received TAM treatment 7 weeks before. (F) Frequency of KSL cells in indicated mice. (G) Colony growth from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control (n = 7 each) total BM cells 7 weeks after TAM treatment. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (H) Blood donor cell chimerism after competitive transplantation of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ donor cells that were transplanted 7 weeks after TAM induction. (I) SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ donor LT-HSCs 16 weeks after competitive transplantation. Data from 5 independent experiments are shown. HCT, hematocrit; M, myeloid cells; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PLT, platelet.

LT-HSC-specific depletion of Setd1a is dispensable for survival but critically important for HSC function after transplantation. (A) Experimental outline for TAM treatment of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control mice and competitive transplantations using Lin− BM cells. (B) Survival of TAM-treated SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control mice (n = 6 each). (C) Blood parameters in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice 7 weeks after TAM treatment. Data are pooled from 5 (n = 16) independent experiments. (D) CD3+ T cells, B220+ B cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells in the spleen of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control animals that have received TAM treatment 7 weeks before. (E) Numbers of LT- HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control mice that have received TAM treatment 7 weeks before. (F) Frequency of KSL cells in indicated mice. (G) Colony growth from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or control (n = 7 each) total BM cells 7 weeks after TAM treatment. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (H) Blood donor cell chimerism after competitive transplantation of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ donor cells that were transplanted 7 weeks after TAM induction. (I) SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ donor LT-HSCs 16 weeks after competitive transplantation. Data from 5 independent experiments are shown. HCT, hematocrit; M, myeloid cells; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PLT, platelet.

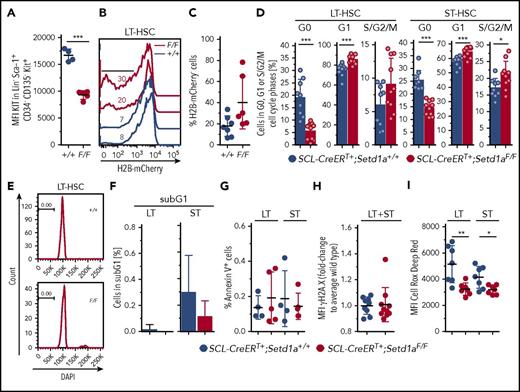

Impaired LT-HSC and HPC expansion in the absence of SETD1A

Most immature LT-HSCs express intermediate levels of the receptor KIT, which is transiently elevated upon activation.30,33 5-FU stimulated HSCs also have reduced KIT expression.29,34 LT-HSCs from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice expressed low levels of KIT (Figure 4A), suggesting either that they are potent LT-HSCs or that they are stimulated and proliferating HSCs. To discriminate between these possibilities, we compared the proliferative capacity of SETD1A-depleted individual LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs from TAM-treated SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice. In vitro, both SETD1A-deficient LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs showed a significantly reduced division rate (supplemental Figure 2L). However, in vivo, SETD1A-deficient LT-HSCs seem to replicate more than do wild-type controls, as is shown by an in situ pulse chase experiment using SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F;R.26-rtTAki/ki;Col1a1-tetO-H2B-mCherryki/ki mice (Figure 4B-C) and ex vivo cell cycle analysis (Figure 4D). Cycling activity of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F LT-HSCs in situ was not accompanied by increased apoptosis, as was evaluated by the lack of accumulation of cells containing fragmented DNA (subG1; Figure 4E-F) or annexin V positivity (Figure 4G). Also, there were no differences in γH2A.X levels, which are indicative for double-strand DNA breaks (Figure 4H). However, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which usually accumulate in metabolically active cells and provoke oxidative stress, limiting the life span of HSPCs in vivo,35 was reduced in the absence of SETD1A (Figure 4I). Together, these data suggest that Setd1a-deficient LT-HSCs and progenitor cells can contribute to hematopoiesis in vivo but have reduced expansion potential under experimental conditions after isolation from the mouse.

Nontransplanted SETD1A-deficient HSCs are defective. (A) Plot depicts mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of Kit expression on LT-HSCs. (B) Plot shows the dilution of H2B-mCherry in LT-HSCs 8 weeks after doxycycline-mediated labeling of LT-HSCs in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F;R.26-rtTAki/ki;Col1a1-tetO-H2B-mCherryki/ki or control mice. (C) Quantification of H2B-mCherry dilution as is shown in panel B. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (D) Frequencies of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ LT-HSCs (left) and ST-HSCs (right) in G0 (Ki-67− DAPI−), G1 (Ki-67+ DAPI−), or S/G2/M (DAPI+) phases of the cell cycle. Data from 2 independent experiments using n = 9 (+/+) and n = 10 (F/F) mice, 8 and 9 days after last TAM treatment are shown. (E) Histogram of DAPI-stained LT-HSCs. (F) Frequency of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs containing fragmented DNA (sub-G1) was determined, as is shown in panel E. Data from 2 experiments using n = 9 (+/+) and n = 10 (F/F) mice were pooled. (G) Frequencies of annexin V+ cells in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in vivo. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (H) Graphs show the MFI for phosphorylated histone 2A.X at Ser139 (γH2A.X) in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in vivo. Data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (I) MFI of Cell Rox Deep Red to detect ROS levels in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in vivo. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown.

Nontransplanted SETD1A-deficient HSCs are defective. (A) Plot depicts mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of Kit expression on LT-HSCs. (B) Plot shows the dilution of H2B-mCherry in LT-HSCs 8 weeks after doxycycline-mediated labeling of LT-HSCs in SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F;R.26-rtTAki/ki;Col1a1-tetO-H2B-mCherryki/ki or control mice. (C) Quantification of H2B-mCherry dilution as is shown in panel B. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (D) Frequencies of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ LT-HSCs (left) and ST-HSCs (right) in G0 (Ki-67− DAPI−), G1 (Ki-67+ DAPI−), or S/G2/M (DAPI+) phases of the cell cycle. Data from 2 independent experiments using n = 9 (+/+) and n = 10 (F/F) mice, 8 and 9 days after last TAM treatment are shown. (E) Histogram of DAPI-stained LT-HSCs. (F) Frequency of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs containing fragmented DNA (sub-G1) was determined, as is shown in panel E. Data from 2 experiments using n = 9 (+/+) and n = 10 (F/F) mice were pooled. (G) Frequencies of annexin V+ cells in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in vivo. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (H) Graphs show the MFI for phosphorylated histone 2A.X at Ser139 (γH2A.X) in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in vivo. Data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (I) MFI of Cell Rox Deep Red to detect ROS levels in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in vivo. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown.

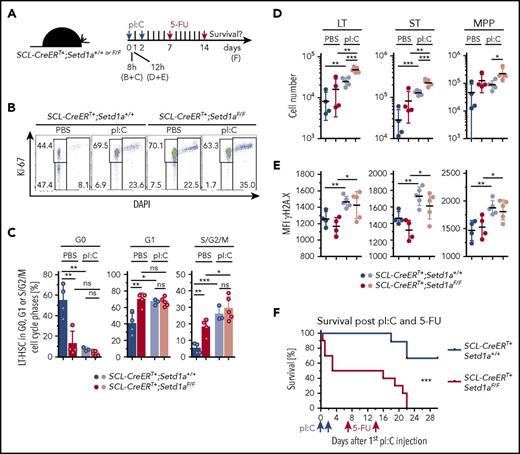

SETD1A sustains multiple DNA repair pathways in HSCs

Key insights were revealed by transcriptome profiling of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F KSLs from BM chimeras (scheme; Figure 5A). Unsupervised clustering confirmed a high data quality (supplemental Figure 3A), and loss of loxP-flanked exon 4 transcripts again revealed efficient recombination of the Setd1aF alleles (supplemental Figure 3B). DAVID comparison with controls revealed that pathways related to DNA repair and stress response were the most affected by SETD1A ablation (Figure 5B; supplemental Table 1). Also strongly downregulated were genes involved in transfer RNA and noncoding RNA metabolism. In comparison with the number of downregulated genes, many fewer genes were upregulated (Figure 5C). This asymmetry concords with the expectation that H3K4 methyltransferases sustain gene expression, and therefore removal should reduce expression of direct targets. Consequently, genes upregulated after SETD1A removal may be indirect targets. The upregulated genes included terms related to protein localization, phosphorylation, and energy metabolism, which may be a consequence of the expansion of ST-HSCs and MPPs within the KSL population (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Table 1).

Loss of Setd1a in HSPCs results in deregulated expression of genes encoding for DNA damage sensing and repair. (A) Experimental outline. (B,C) Plots show biological processes that are enriched in genes downregulated (B) or upregulated (C) in Setd1a-deficient KSL in comparison with wild-type controls. Analysis was performed using the gene ontology (GO)/biological process (BP) database of DAVID. Enrichment scores (log transformation of the DAVID Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer [EASE] score) were calculated to determine overrepresentation of particular biological processes and are indicated on the x-axis. Terms included in the GO pathways are listed in supplemental Table 1. (D) Normalized enrichment scores of the GO categories based on gene sets associated with DNA repair. Negative enrichment scores indicate global downregulation of the genes within the gene set. Terms included in GSEA gene sets are listed in supplemental Table 3. (E) ChIP-qPCR analysis specific for H3K4me3 at promoter regions. Lin− cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice were used, and target genes were selected from RNA sequence data. (F) Photographs from colonies from 600 LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and control mice that were kept in culture for 8 days. The first 4 days, TAM was added to deplete SETD1A expression. Scale bars, 500 μm. (G) Recombination efficiency of the Setd1aF allele in indicated cells. (H) Absolute cell numbers per well after 8 days of culture. Data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (I) Frequency of annexin V+ cells per culture. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (J) Frequencies of TUNEL positive cells of cultivated LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs are shown. Data from 2 independent experiments are pooled. (K) MFI of Cell Rox Deep Red to detect ROS levels in each culture. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. BER, base excision repair; ctrls, controls; DSB, double-strand break; dUTP, deoxyuridine triphosphate; HR, homologous recombination; ncRNA, noncoding RNA; NER, nucleotide excision repair; tRNA, transfer RNA.

Loss of Setd1a in HSPCs results in deregulated expression of genes encoding for DNA damage sensing and repair. (A) Experimental outline. (B,C) Plots show biological processes that are enriched in genes downregulated (B) or upregulated (C) in Setd1a-deficient KSL in comparison with wild-type controls. Analysis was performed using the gene ontology (GO)/biological process (BP) database of DAVID. Enrichment scores (log transformation of the DAVID Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer [EASE] score) were calculated to determine overrepresentation of particular biological processes and are indicated on the x-axis. Terms included in the GO pathways are listed in supplemental Table 1. (D) Normalized enrichment scores of the GO categories based on gene sets associated with DNA repair. Negative enrichment scores indicate global downregulation of the genes within the gene set. Terms included in GSEA gene sets are listed in supplemental Table 3. (E) ChIP-qPCR analysis specific for H3K4me3 at promoter regions. Lin− cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice were used, and target genes were selected from RNA sequence data. (F) Photographs from colonies from 600 LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and control mice that were kept in culture for 8 days. The first 4 days, TAM was added to deplete SETD1A expression. Scale bars, 500 μm. (G) Recombination efficiency of the Setd1aF allele in indicated cells. (H) Absolute cell numbers per well after 8 days of culture. Data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (I) Frequency of annexin V+ cells per culture. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (J) Frequencies of TUNEL positive cells of cultivated LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs are shown. Data from 2 independent experiments are pooled. (K) MFI of Cell Rox Deep Red to detect ROS levels in each culture. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. BER, base excision repair; ctrls, controls; DSB, double-strand break; dUTP, deoxyuridine triphosphate; HR, homologous recombination; ncRNA, noncoding RNA; NER, nucleotide excision repair; tRNA, transfer RNA.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that LT-HSC signature genes36 were globally downregulated (supplemental Figure 3C), whereas LSK CD48+ (ST-HSC) signature genes were globally upregulated (supplemental Figure 3D, supplemental Table 2). These data can be due to the increase in the frequency of ST-HSCs and MPPs in R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F BM chimeric mice (Figure 2D-E) but may also suggest a role for SETD1A in maintaining the transcriptional identity of LT-HSCs.

As for the DAVID analysis, GSEA also revealed significant underrepresentation (false discovery rate < 0.25) of multiple gene sets related to DNA repair and DNA damage response (Figure 5D; supplemental Table 3). In fact, differential expression analysis revealed that transcripts important for virtually every DNA damage detection and repair pathway were significantly downregulated (Padj ≤ .05), including homologous recombination and replication fork repair (Rad50, Rad51b, Rad51c, Zswim7, Recql, Rpain, Bre, Fam175a, Emsy, Eme1, Fbxo18), nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ; Prkdc, Nhej1), nucleotide excision repair (Gtf2h3, Gtf2h4, Rad23a), base excision repair (Parp2), DNA interstrand cross-link repair (Dclre1a, Fancg, Fancd2, Fanci), direct damage reversal (Mgmt), and protection from oxidative stress (Ogg1, Nudt1), mismatch repair system (Mlh1), translesion DNA synthesis (Poli), R-loop processing (Rnaseh1), telomere homeostasis (Pot1a), and cell cycle progression and checkpoint activation (Rad1, Mcts1, Tbrg1, Rbx1, Fbox6). Accordingly, deletion of Setd1a in Lin− cells causes downregulation of H3K4me3 on these promoters, but not on an intergenic region on chromosome 9 (Figure 5E). These transcriptome and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) qPCR data suggest that SETD1A ablation in HSPCs impairs DNA damage responses and repair, which in turn may perturb the cycling activity of SETD1A-deficient HSPCs in vitro and in vivo.

These conclusions were first tested using in vitro cultivation of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs from R.26CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and control mice (Figure 5F). Setd1a was efficiently deleted by TAM induction in vitro (Figure 5G), resulting in significantly reduced cell expansion (Figure 5F,H), likely due to increased apoptosis (Figure 5I) and DNA damage (Figure 5J). Notably, in agreement with the in vivo data, ROS levels were reduced in R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in culture (Figure 5K), indicating that ROS production is not the cause of DNA damage.

Taken together, SETD1A regulates the expression of many components of DNA damage detection and repair pathways, and the specific ablation of SETD1A expression in HSPCs results in impaired colony growth and in the accumulation of DNA breaks in LT- and ST-HSCs.

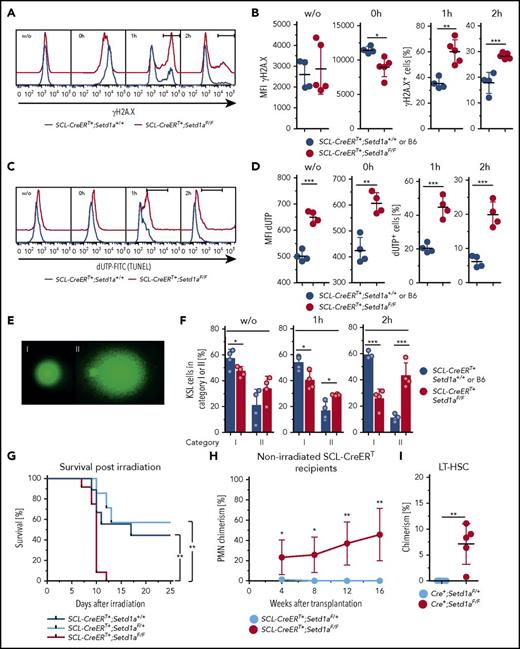

SETD1A is crucial for DNA repair after irradiation and confers radioresistance in vivo

We then used SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice to examine responses to DNA damage in vivo. Directly after irradiation (10 Gy, 0 hour), SETD1A-deficient KSL showed reduced levels of γH2A.X (Figure 6A-B), indicating reduced activation of the DNA break-sensing machinery. Also, the subsequent disappearance of γH2A.X was delayed, suggesting that DNA repair was impaired (Figure 6A-B). Notably, SETD1A-deficient KSL cells showed constitutively increased DNA breaks as detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL), and repair was again delayed (Figure 6C-D). Both constitutively elevated levels of DNA breaks and delayed DNA break repair were confirmed by the comet assay (Figure 6E-F).

SETD1A-deficieny results in defective DNA repair-mediating increased radiosensitivity in vivo. (A-F) KSL cells 7 to 9 weeks after TAM treatment from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control animals were analyzed for DNA damage-signaling and repair ex vivo and after irradiation (10 Gy). (A) Representative FACS of KSL cells for phosphorylated histone 2A.X at Ser139 (γH2A.X). (B) Graphs showing the MFI for γH2A.X ex vivo (left) and directly after irradiation (second from left). The percentages of γH2A.X+ cells at 1 hour (second from right) and at 2 hours (right) after irradiation are shown (F/F, n = 5; +/+ n = 4). Data are from 2 independent experiments. (C) Representative FACS of KSL cells for DNA breaks detected by TUNEL assay before and after irradiation. (D) Graphs showing the MFI for TUNEL label ex vivo (left) and directly after irradiation (second from left). The percentages of TUNEL+ cells at 1 hour (second from right) and at 2 hours (right) after irradiation are shown (F/F, n = 4; +/+ n = 2). Data are from 2 pooled and 3 individual SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice and from pooled SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ mice from 2 independent experiments (3 and 4 mice). (E) Comet assay to detect DNA breaks (20× objective; Vista Green DNA dye supplied in the Kit). Undamaged cells (category I, left) and significantly damaged cells (hedgehog shape, category II, left) were scored. (F) Frequencies of KSL cells in category I or II without irradiation (left), 1 hour after irradiation (middle), and 2 hours after irradiation (right) (F/F n = 4, +/+ n = 4). (G) Survival of TAM-treated (9 and 12 weeks beforehand) SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice (red line, n = 12), SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/+ mice (light blue line, n = 7), and SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ mice (blue line, n = 9) after irradiation with 6.6 Gy. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (H) Donor cell contribution to blood PMNs after transplantation of 3 × 106 wild-type Lin− BM cells into nonconditioned SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F (red line, n = 5) or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/+ (blue line, n = 5) recipient mice that were TAM induced 7 weeks before. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Wild-type donor-cell contribution to the LT-HSC compartment of nonconditioned SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/+ recipients 16 weeks after transplantation.

SETD1A-deficieny results in defective DNA repair-mediating increased radiosensitivity in vivo. (A-F) KSL cells 7 to 9 weeks after TAM treatment from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control animals were analyzed for DNA damage-signaling and repair ex vivo and after irradiation (10 Gy). (A) Representative FACS of KSL cells for phosphorylated histone 2A.X at Ser139 (γH2A.X). (B) Graphs showing the MFI for γH2A.X ex vivo (left) and directly after irradiation (second from left). The percentages of γH2A.X+ cells at 1 hour (second from right) and at 2 hours (right) after irradiation are shown (F/F, n = 5; +/+ n = 4). Data are from 2 independent experiments. (C) Representative FACS of KSL cells for DNA breaks detected by TUNEL assay before and after irradiation. (D) Graphs showing the MFI for TUNEL label ex vivo (left) and directly after irradiation (second from left). The percentages of TUNEL+ cells at 1 hour (second from right) and at 2 hours (right) after irradiation are shown (F/F, n = 4; +/+ n = 2). Data are from 2 pooled and 3 individual SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice and from pooled SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ mice from 2 independent experiments (3 and 4 mice). (E) Comet assay to detect DNA breaks (20× objective; Vista Green DNA dye supplied in the Kit). Undamaged cells (category I, left) and significantly damaged cells (hedgehog shape, category II, left) were scored. (F) Frequencies of KSL cells in category I or II without irradiation (left), 1 hour after irradiation (middle), and 2 hours after irradiation (right) (F/F n = 4, +/+ n = 4). (G) Survival of TAM-treated (9 and 12 weeks beforehand) SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice (red line, n = 12), SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/+ mice (light blue line, n = 7), and SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ mice (blue line, n = 9) after irradiation with 6.6 Gy. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (H) Donor cell contribution to blood PMNs after transplantation of 3 × 106 wild-type Lin− BM cells into nonconditioned SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F (red line, n = 5) or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/+ (blue line, n = 5) recipient mice that were TAM induced 7 weeks before. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Wild-type donor-cell contribution to the LT-HSC compartment of nonconditioned SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/+ recipients 16 weeks after transplantation.

Furthermore, SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice were significantly more radiosensitive than were controls (Figure 6G). Moreover, wild-type donor HSPCs transplanted into nonconditioned TAM-induced congenic SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice engrafted efficiently and contributed to blood neutrophil production over 16 weeks (Figure 6H), suggesting that SETD1A contributes to the competitiveness of HSCs in situ. Consistently, the HSC compartment was chimeric, suggesting that SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F LT-HSCs were out-competed by wild-type LT-HSCs (Figure 6I). We conclude that SETD1A orchestrates the expression of DNA damage-sensing and repair pathways, and these deficiencies mediate hypersensitivity of ablated HSPCs to irradiation insult and loss of competitiveness in comparison with wild-type LT-HSCs.

SETD1A is a key mediator protecting HSCs from activation-induced attrition in response to inflammatory stimulation

To further test for the physiological relevance of SETD1A-mediated defects in vivo, we activated HSCs of TAM-induced SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice by injecting pI:C, which activates toll-like receptor 3 (scheme; Figure 7A). HSC activation is characterized by cell cycle entry, which makes mice highly sensitive to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU 4 ). Furthermore, resolution of inflammation-mediated activation of HSPCs depends on a functional Fanconi anemia DNA damage repair pathway.5 Without additional challenge, SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice were as sensitive to 5-FU treatment as were controls (supplemental Figure 3E). In contrast, SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice were more sensitive to activation-induced attrition than were wild-type mice. We first confirmed that loss of SETD1A in LT-HSCs resulted in G0-to-G1 transition and progression through the cell cycle (Figure 7B-C). pI:C treatment also resulted in increased cycling activity of LT-HSCs (Figure 7B-C). As a consequence, cell numbers of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs increased (Figure 7D), and increased γH2A.X labeling indicated accumulating DNA damage (Figure 7E). Half of SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice succumbed to pI:C treatment, suggesting increased sensitivity to type I interferon-induced inflammation (Figure 7F). The mice that survived pI:C treatment were found exquisitely sensitive to 5-FU treatment in comparison with wild-type mice (Figure 7F). We suggest that the functional decline of SETD1A-depleted HSPCs under physiologic inflammatory conditions may be based on receding genomic integrity and that SETD1A coordinates the expression of DNA damage recognition and repair components that help rescuing HSPCs from activation-induced attrition in vivo.

SETD1A protects mice from activation-induced lethality. (A) SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ mice were injected twice with pI:C and 7 and 14 days later with 5-FU. TAM-induced depletion of Setd1a was conducted 2 to 4 weeks beforehand. (B) Dot plots show the activation of LT-HSCs 8 hours after pI:C injection, resolving LT-HSCs for the expression of Ki-67 and DAPI staining. (C) Plots summarize the distribution of LT-HSCs in cell cycle phases as determined using the staining shown in panel B. Data from 2 independent experiments were pooled. Mice were used 3 to 4.5 weeks after the last TAM treatment. Differences in comparison with Figure 4D may be due to the time gap between TAM induction and analysis.50 (D) Plots showing cell numbers of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice 12 hours after pI:C (light circles) or PBS (dark circles) treatment. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (E) Plots showing MFI of H2A.X labeling of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice 12 hours after pI:C (light circles) or PBS (dark circles) treatment. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (F) Survival plot after pI:C and 5-FU treatment. Data are summarized from 2 independent experiments using 10 SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice and 9 control mice.

SETD1A protects mice from activation-induced lethality. (A) SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F or SCL-CreERT+;Setd1a+/+ mice were injected twice with pI:C and 7 and 14 days later with 5-FU. TAM-induced depletion of Setd1a was conducted 2 to 4 weeks beforehand. (B) Dot plots show the activation of LT-HSCs 8 hours after pI:C injection, resolving LT-HSCs for the expression of Ki-67 and DAPI staining. (C) Plots summarize the distribution of LT-HSCs in cell cycle phases as determined using the staining shown in panel B. Data from 2 independent experiments were pooled. Mice were used 3 to 4.5 weeks after the last TAM treatment. Differences in comparison with Figure 4D may be due to the time gap between TAM induction and analysis.50 (D) Plots showing cell numbers of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice 12 hours after pI:C (light circles) or PBS (dark circles) treatment. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (E) Plots showing MFI of H2A.X labeling of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs from SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F and control mice 12 hours after pI:C (light circles) or PBS (dark circles) treatment. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (F) Survival plot after pI:C and 5-FU treatment. Data are summarized from 2 independent experiments using 10 SCL-CreERT+;Setd1aF/F mice and 9 control mice.

Discussion

We observed that SETD1A prevented the accumulation of DNA lesions through both the speed of DNA damage signaling and DNA repair. Both processes were delayed by the absence of SETD1A. These delays suggest that SETD1A may be a direct and integral coordinator of DNA damage response in HSPCs. Furthermore, loss of Setd1a in HSCs rendered mice hypersensitive to inflammatory HSC activation and subsequent antiproliferative treatment, again placing SETD1A at the center of the orchestrated expression of DNA damage-signaling and repair components.

Vav-Cre-mediated deletion of Setd1a results in a constitutive lack of expression of SETD1A in definitive HSCs from the time point of their emergence during embryonic development. The severe reduction of KSL cells suggests that definitive HSCs are not generated or expanded during pre- and neonatal development. In contrast, HSCs in adult mice are largely quiescent and phenotypically maintained after depletion of Setd1a, suggesting that Setd1a is important for HSC division under conditions of proliferative pressure. In line with this interpretation is the finding that cell growth in vitro is blunted but not completely abrogated in the absence of Setd1a, suggesting that HSCs have the capacity to divide in the absence of Setd1a but fail to do so excessively.

Ubiquitous loss of Setd1a in mice led to rapid death concomitant with a severe drop in blood cell counts as well as a reduced frequency of precursor cells in the BM. However, upon HSC-specific Setd1a depletion, phenotypically defined HSCs were maintained but were functionally impaired. Setd1a-deleted HSCs lost their ability to reconstitute multiple lineages and displayed a competitive disadvantage in comparison with wild-type HSCs. As is shown by expression profiling and functional assays, the role of SETD1A can be primarily attributed to the expression of genes crucial for DNA damage detection and repair. HSCs lacking SETD1A accumulate DNA breaks and consequently fail to recover under conditions of replicative stress such as transplantation or irradiation-induced regeneration. We conclude that SETD1A protects HSCs from DNA damage-induced loss of functionality and productivity. The lethality provoked by R.26-CreERT2-mediated conditional deletion indicates that SETD1A is also required later in hematopoiesis. However, SETD1A is not simply required in all cell types, because conditional deletion using CD4-Cre had no impact.

SETD1A is not required for maintaining phenotypic LT-HSCs in situ. However, it is critically important for the maintenance of HSC identity characterized by gene expression and function, and viability in the absence of LT-HSCs is consistent with the survival of mice after loss of most LT-HSCs under steady-state conditions.37 LT-HSC-specific loss of SETD1A was accompanied by the absence of HSPC function under stress situations in situ and after transplantation. This phenotype is similar to the loss of DNA repair genes in hematopoiesis. In particular, HSCs lacking DNA damage-related genes involved in homologous recombination (eg, Fancd2, Fancc), nonhomologous end joining (eg, Ku80, Lig4), mismatch repair (eg, Ercc1, Xpd), or DNA damage sensing (eg, ATM, ATR) display a dramatic loss of their reconstitution potential. However, young mutant mice contain HSCs under homeostatic conditions.38-40 Indeed, the balance between the imperative to preserve the genomic integrity of stem cells and the need to retain stem cell pools has promoted studies on the role of the DNA damage response in stem cell decisions.6,41 To this discussion we now add the critical role that SETD1A plays in HSCs to sustain the expression of genes involved in the maintenance of genomic integrity and the possibility that it also regulates aspects of stem cell proliferation. Possibly, SETD1A sits at the center of this balance and integrates the outcome.

Hematopoiesis-specific depletion of MLL1,16 MLL4,19 DPY30,20 or CFP121 resulted in comparable HSC phenotypes characterized by loss of stem cell identity and accumulation of nonfunctional KSL cells, together with lack of repopulation activity. Hematopoiesis in the absence of MLL5 (Kmt2e), a methyltransferase-incompetent SET domain protein, also showed a comparable stem cell phenotype.42 Detailed analysis of these conditional knockouts assigned the defects to deregulated expression of specific self-renewal genes, including Mecom and Prdm16 in the absence of the H3K4 HMT Mll1, lineage-determining genes such as Lmo-2 in the absence of Dpy30, or genes that protect from oxidative stress, as has been described in Mll4- and Mll5-deficient mice.19,20,43 In Mll4- and Mll5-deficient HSCs the accumulation of ROS and resulting DNA damage was suggested as the underlying reason for the decline of HSC function. In contrast, HSC dysfunction in the absence of SETD1A occurred independently from the accumulation of mitochondrial ROS. Many genes that are important for virtually all DNA repair pathways were downregulated, and consequently SETD1A-deficient HSPCs accumulated DNA breaks.

The functional relevance of the 6 Set1/Trithorax-type methyltransferases has usually been equated with H3K4 methylation, which is the principal epigenetic characteristic of active chromatin. However, the H3K4 methyltransferase activity of MLL1 has no relevance to its essential role in definitive hematopoiesis and leukemiogenesis.44 Similarly, MLL3 and MLL4 do not rely upon H3K4 methylation to act as coactivators.45 In contrast, the H3K4 methyltransferase activity of SETD1A may be integral to its function. In cancer cell lines46 and ES cells,22 SETD1A is the major H3K4 methyltransferase, as is the sole Set1 homolog in flies.47,48 SETD1A is also the major H3K4 methyltransferase in KSL cells (Figure 1H; supplemental Figure 2B). However, it is important to note that it is not essential in all cell types, as we show here for thymocytes and was shown previously in the early embryo.22 DPY30 is a common component of all 6 Set1/Mll complexes, and its conditional knockout in hematopoiesis resulted in reduced H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethylation.20 Our results imply that DPY30-mediated global loss of H3K4 methylation can be assigned to the SETD1A complex. However, whether the methyltransferase activity is decisive for SETD1A action in HSCs and later hematopoiesis requires further studies with SETD1A SET domain mutations. Recently, we reported that SETD1B regulates gene expression of a specific aspect of late oogenesis.49 Here we report that SETD1A regulates the expression of many genes involved in DNA repair in HSCs. Among the enigmatic functions of the H3K4 methyltransferases, these findings indicate that they can serve as regulators of specific gene-expression programs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the animal houses at the Max Planck Institute and Medical Theoretical Center for great care of mouse husbandry and the Core Facility Cellular Imaging for their help. The authors are grateful to Joachim Göthert for providing SCL-CreERT mice. The authors thank Patricia Ernst for advice on the experiments and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (WA2837, FOR2033-A03, TRR127-A5) (C.W.) and by a grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2013_A262) (C.W., A.K., and A.F.S.). M.D.V. is a Helmholtz Young Investigators Group leader (Helmholtz Association).

Authorship

Contribution: K.A., A.K., J.F., and A.S.B. performed experiments and analyzed data; K.A., A.K., A.F.S., and C.W. designed experiments and interpreted data; M.D.V. interpreted data; M.L. and A.D. performed next-generation sequencing and data analysis; A.J. and T.H. conducted gene set enrichment analysis; A.K. and C.W. conceived of the study; and K.A., A.F.S., and C.W. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Claudia Waskow, Regeneration in Hematopoiesis, Leibniz Institute on Aging, Fritz Lipmann Institute, Beutenbergstr 11, 07745 Jena, Germany; e-mail: claudia.waskow@leibniz-fli.de.

References

Author notes

K.A. and A.K. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Setd1a expression in postnatal hematopoietic cells is crucial for survival. (A) Normalized RNA-sequence counts for Mll1, Mll2, Mll3, Mll4, Setd1a, and Setd1b in KSL Slam LT-HSCs (lineage− = Lin−, Kit+ Sca-1+ [KSL] CD48/41− CD150+ CD34− CD135−). Shown is the average of 3 replicates of 1 experiment. (B) qPCR of Setd1a transcripts in LT-HSCs (KSL CD34− CD135−), ST-HSCs (KSL CD34+ CD135−), MPPs (KSL CD34+ CD135+), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; Lin− Kit+ Sca-1− [MP] CD34+ CD16/32−), megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors (MEPs; MP CD34− CD16/32−), and granulocyte macrophage progenitors (GMPs; MP CD34+ CD16/32+) from wild-type mice. Setd1a transcript expression is shown in relation to transcripts of Rpl19. (C) Survival curve of R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red line; n = 7) and control mice (blue line; n = 15) after tamoxifen induction. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (D) Survival curve of Vav-Cre+;Setd1aF/F (red line; n = 17) and control (blue line; n = 15) mice. (E) Experimental outline using R.26-CreERT2+ deleter mice. (F) White and red blood cell counts, hematocrit, hemoglobin, and platelet values from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F (red lines; n = 10) or R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1a+/+ (blue lines; n = 10) chimeric mice before (0 day) and after TAM treatment or untreated wild-type (gray lines; n = 3) controls. (G) Plot shows colony growth 8 days (BFU-E) and 12 days (G, M, GM, and GEMM) after culture of 104 BM cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice (n = 6) that were TAM induced 8 days beforehand. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. (H) Western blot of H3K4me1, H3K4me2, and H3K4me3 in Lin− cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice after 4 days in vivo and 2 days in vitro TAM induction (n = 3 each). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (I) Representative fluorescence-activated cell scan (FACS) plots resolve thymocytes from CD4-Cre+;Setd1aF/F and control mice for the expression of CD4 and CD8. Plots are gated on 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) negative cells. (J) Quantification of CD4 and CD8 single positive thymocytes. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; ns, not significant; Plt, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; SP, single positive; WBC, white blood cell.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/12/10.1182_blood-2017-09-806844/4/m_blood806844f1.jpeg?Expires=1769155296&Signature=L~qPcZUU9FPIazxEwUkSinsnfO2WqbZoyFD8iW7cGPFl8RRal4~rPGYSkAq2N0po2QB~AKGRpclbdJudkE4UeynKPRBRQ5~1FmpZoq6alJzIlvToiJMRoGj~7XD5Rqdgf0hjr~NECtBImSJpFqJY9aPAfsYuHtyTEbszg46GHzX9pFUb-2bWtf8y-Lxe7VMY9r7qI1-BUnAAFugNh282m0M7Q5ZIW4RG-Az4YMkl~x~92PG3oDLMSKtz7zynSjql3uy2izZkszfBwIrM96PQuJ~nrTkT1JnNgB3JxPOPmtZlyDgcw5HtDg1gRcSrzkVwadG35ge2-XuBhS6vkBp24Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Loss of Setd1a in HSPCs results in deregulated expression of genes encoding for DNA damage sensing and repair. (A) Experimental outline. (B,C) Plots show biological processes that are enriched in genes downregulated (B) or upregulated (C) in Setd1a-deficient KSL in comparison with wild-type controls. Analysis was performed using the gene ontology (GO)/biological process (BP) database of DAVID. Enrichment scores (log transformation of the DAVID Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer [EASE] score) were calculated to determine overrepresentation of particular biological processes and are indicated on the x-axis. Terms included in the GO pathways are listed in supplemental Table 1. (D) Normalized enrichment scores of the GO categories based on gene sets associated with DNA repair. Negative enrichment scores indicate global downregulation of the genes within the gene set. Terms included in GSEA gene sets are listed in supplemental Table 3. (E) ChIP-qPCR analysis specific for H3K4me3 at promoter regions. Lin− cells from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F or control mice were used, and target genes were selected from RNA sequence data. (F) Photographs from colonies from 600 LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs from R.26-CreERT2+;Setd1aF/F and control mice that were kept in culture for 8 days. The first 4 days, TAM was added to deplete SETD1A expression. Scale bars, 500 μm. (G) Recombination efficiency of the Setd1aF allele in indicated cells. (H) Absolute cell numbers per well after 8 days of culture. Data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (I) Frequency of annexin V+ cells per culture. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (J) Frequencies of TUNEL positive cells of cultivated LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs are shown. Data from 2 independent experiments are pooled. (K) MFI of Cell Rox Deep Red to detect ROS levels in each culture. Data from 2 independent experiments are shown. BER, base excision repair; ctrls, controls; DSB, double-strand break; dUTP, deoxyuridine triphosphate; HR, homologous recombination; ncRNA, noncoding RNA; NER, nucleotide excision repair; tRNA, transfer RNA.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/12/10.1182_blood-2017-09-806844/4/m_blood806844f5.jpeg?Expires=1769155296&Signature=iUgDnfw~NK2NmnAB6Ju2nWBOWFkPgDlzy0Yb08LUCmvibNx6kxjWzx-EfSRxMk3vHoKiIcrxx0tpvbXgyC5IV07rJZBVBSWIeffhXBl~Bhzii0ySyc3Z1UCEBgLFBNC7vSXK1J9ghwp04EktN6FqKFlzj4IxhpraAwUVIrBK3-pCSu0My3dYqxgJnNDiyuIZVw~XdAXz4uQOogx0k4lhFCkCBjg5ATBz64I-KMCgZbBLvQp79xocqm3BL4Hvn7vi4QVVJ33ucxlD~1K771kpWiW3FgvuXrOHiNQMSMBKG8rx-~zkCBdMrX0AkcMBVpSmGYpPQdv5nRpT0mwQXjbFCA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal