Abstract

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) is an unusual B-cell–derived malignancy in which rare malignant Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells are surrounded by an extensive but ineffective inflammatory/immune cell infiltrate. This striking feature suggests that malignant HRS cells escape immunosurveillance and interact with immune cells in the cancer microenvironment for survival and growth. We previously found that cHLs have a genetic basis for immune evasion: near-uniform copy number alterations of chromosome 9p24.1 and the associated PD-1 ligand loci, CD274/PD-L1 and PDCD1LG2/PD-L2, and copy number–dependent increased expression of these ligands. HRS cells expressing PD-1 ligands are thought to engage PD-1 receptor–positive immune effectors in the tumor microenvironment and induce PD-1 signaling and associated immune evasion. The genetic bases of enhanced PD-1 signaling in cHL make these tumors uniquely sensitive to PD-1 blockade.

Introduction to Hodgkin lymphoma and tumor microenvironment

Classical Hodgkin lymphomas (cHLs) include rare malignant Reed-Sternberg cells within an extensive inflammatory/immune cell infiltrate. In cHLs, less than 2% of the cells are Hodgkin and Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells; the remainder include macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, mast cells, and T cells.1

What causes the influx of T cells into the cHL microenvironment? HRS cells produce chemokines such as CCL5, CCL17/TARC, and CCL22/MDC, whereas CD4+ T-cell subsets express receptors for these factors.2,3 As a result, HRS cells attract these T-cell subsets into the cHL microenvironment. Additionally, HRS cells secrete CCL5 to attract macrophages and mast cells4 and interleukin-8 (IL-8) to attract neutrophils.2 The extensive but ineffective immune/inflammatory cell infiltrates in cHL suggest that HRS cells have developed mechanisms to escape immunosurveillance while relying on microenvironmental signals for survival and growth. Indeed, HRS cells secrete CCL17 and CCL22 to attract immunosuppressive CCR4+ Tregs into the cHL microenvironment to evade immune attack.5 Moreover, HRS cells and Tregs in the cHL microenvironment secrete immunosuppressive IL-10 to inhibit the function of infiltrating natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells.2

Key pathways used by HRS cells for survival and growth

HRS cells are derived from crippled germinal center B cells that have lost expression of certain B-cell surface proteins, including the B-cell receptor (BCR).1,6 Mature B cells devoid of BCRs would normally die by apoptosis. Therefore, HRS must rely on alternative deregulated signaling pathways for survival and growth, as discussed later.

NF-κB

The canonical and noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathways are constitutively activated in HRS cells to promote their survival and proliferation. The robust NF-κB activity in HRS cells is mediated by dual mechanisms: (1) inactivation of the negative regulators of NF-κB (eg, TNFAIP3, NFKBIA, NFKBIE, TRAF3, and CYLD) by point mutations or deletions,7,8 and (2) amplification of the positive regulators or the components of the NF-κB pathway (eg, NIK and REL) by copy number gains.9,10

JAK/STAT

The Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway, which is vital to signaling by many cytokine transmembrane receptors, transmits survival, proliferation, and differentiation cues. STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 are highly expressed and activated in cHL.11,12 Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway promotes tumor cell proliferation and survival in cHL. The JAK2 gene is frequently amplified in cHL.9,13 Moreover, negative regulators of JAK/STAT signaling pathway (eg, SOCS1 and PTPN1) in HRS cells are recurrently inactivated by mutations or deletions.14,15

AP-1

Activator protein-1 (AP-1) is a dimeric transcription factor composed of proteins from the Jun (c-Jun, JunB, and JunD), Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra1, and Fra2), and activating transcription factor family members. AP-1 is constitutively activated in HRS cells, which express high levels of c-Jun and JunB.16

TNF receptor family

HRS cells express tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family proteins, such as CD30, CD40, CD95, transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI), B-cell mutation antigen (BCMA), and RANK.1 Engagement of these cell surface receptors by their respective ligands activates downstream signaling pathways and augments canonical and alternative NF-κB activity.10

Additional perturbed pathways

Immunosuppressive mechanisms

Multiple stratagems leveraged by cHL to escape immunosurveillance include (1) reduction or loss of antigen presentation through B2M inactivating mutations/deletion (perturbing major histocompatibility complex [MHC] class I) and/or CIITA inactivating alterations (perturbing MHC class II)22,23 ; (2) secretion of soluble factors, such as IL-10, transforming growth factor β1, prostaglandin and galectin-1, to kill or inhibit the activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and/or professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs)2,24-27 ; (3) recruitment of abundant immunosuppressive Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells into the cHL microenvironment28 ; and (4) enhanced PD-1 signaling via interaction of HRS cells expressing the PD-1 ligands with PD-1 receptor+ immune effectors.29,30

PD-1/PD-L1 coinhibitory pathway

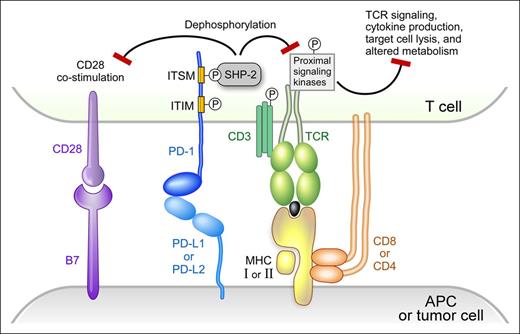

Activation of T cells requires 2 signals. Signal 1 (stimulation by a specific antigen) is mediated by the interaction of the T-cell receptor (TCR) with a MHC-bound antigen presented on the surface of APCs. Signal 2 (costimulation by coreceptors) is mediated by binding of B7-1 (CD80) or B7-2 (CD86) on the surface of the APC to CD28 on the surface of the T cells.31,32 The strength and duration of T-cell activation is modulated by signaling pathways of coinhibitory receptors, such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death protein-1 (PD-1).33

PD-1 is expressed on activated T cells, but not on resting T cells.33 In addition, PD-1 is also expressed on natural killer cells, B cells, macrophages, Tregs, and follicular T cells.33,34 PD-1 has 2 ligands, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death-ligand 2 (PD-L2). PD-L1 is highly expressed on the surface of tumor-infiltrating macrophages, dendritic cells (professional APC), and malignant cells of certain solid tumors and lymphomas, including cHL (Figure 1).29,33 Binding of PD-1 by its ligands, PD-L1 or PD-L2, results in crosslinking of the antigen-TCR complex with PD-1. This event leads to phosphorylation of the tyrosine residue in the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (TxYxxL/I) of PD-1 and recruitment of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, which dephosphorylates and inactivates ZAP70 in T cells (Figure 1).31-33,35,36 The final outcome is the attenuation or shutdown of TCR-associated downstream signaling including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and RAS–MEK–extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways, downregulation of cytokine production (eg, TNF-α and IL-2), and inhibition of T-cell proliferation.31-33 Furthermore, PD-L1 competes with CD28 for binding to its ligand, CD80 (B7-1), and inhibits CD28 costimulation (signal 2 in T-cell activation).37 PD-1/PD-L1 signaling results in T-cell exhaustion/energy, which is a temporary and reversible inhibition of T-cell activation and proliferation. PD-1 signaling also shifts the metabolism of activated T-cells from glycolysis and glutaminolysis to fatty acid oxidation, limiting T effector cell differentiation and function.38

PD-1 signaling. Modified version reprinted with permission from Baumeister, SH et al, 2016; Annu. Rev. Immunol. 34:539-73.

PD-1 signaling. Modified version reprinted with permission from Baumeister, SH et al, 2016; Annu. Rev. Immunol. 34:539-73.

Recent studies reveal an additional role for the PD-1 pathway in modulating CD28 signaling.39,40 Specifically, PD-1–recruited SHP-2 preferentially dephosphorylates CD28 over the TCR intrinsic subunit CD3ζ and its signaling components, including TCR-associated ZAP70 and its downstream adaptors LAT and SLP76 (Figure 1). These studies suggest that (1) CD28 is the preferential immediate downstream target of PD-1 signaling, and (2) PD-1 suppresses T-cell functions primarily by inhibiting signal 2 (costimulation by CD28) rather than signal 1 (TCR stimulation by antigen).

Physiologic roles of PD-1 negative signaling include (1) balancing positive signals transduced through TCR and costimulatory receptors; (2) downregulating the immune response after elimination of disease; (3) limiting the strength of an immune response to prevent tissue damage, autoimmune diseases, and allergic diseases; and (4) maintaining immune tolerance.31-33 Various cancers and viruses have exploited and hijacked coinhibitory signaling pathways such as PD-1 to escape destruction by the immune system. These inhibitory effects can be reversed by blocking PD-1/PD-L1 signaling at the level of the PD-1 receptor or the PD-1 ligand.33,41

Genetic basis of increased PD-1 signaling in cHL

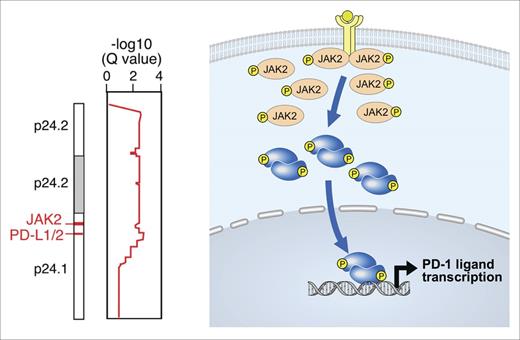

In previous studies, we integrated high-resolution copy number data with transcriptional profiling information to identify PD-L1 and PD-L2 as the major targets of 9p24.1 copy gain in cHL cell lines and laser capture microdissected HRS cells (Figure 2, left panel).29 In cHL cell lines and primary tumors, there was a 9p24.1 copy number–dependent increase in PD-L1 protein expression.29 In cHL, the extended 9p24.1 amplicon almost always includes JAK2 (Figure 2, left panel). This finding is noteworthy because JAK2 copy gain leads to increased JAK2 protein expression and JAK/STAT signaling, which further induces PD-1 ligand expression (Figure 2, right panel).29 Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP 1) also induces PD-L1 expression via AP-1 and JAK/STAT pathways, highlighting an additional viral basis for PD-L1 upregulation in Epstein-Barr virus + cHL.42,43

PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy gain and further induction via JAK2/STAT signaling. (Left) The 9p24.1 amplicon in cHL includes PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2. (Right) JAK2 copy gain leads to increased JAK2 protein expression and enhanced JAK/STAT signaling, which further induces PD-1 ligand expression.

PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy gain and further induction via JAK2/STAT signaling. (Left) The 9p24.1 amplicon in cHL includes PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2. (Right) JAK2 copy gain leads to increased JAK2 protein expression and enhanced JAK/STAT signaling, which further induces PD-1 ligand expression.

Analyses of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway alterations in newly diagnosed cHL

Due to the rarity of neoplastic HRS cells in primary cHL, it is not feasible to perform comprehensive genomic analyses of intact biopsy specimens. For this reason, we recently developed a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay to directly and precisely characterize copy number alterations (CNAs) of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens from patients with newly diagnosed cHL who were treated with a current induction regimen (Stanford V) and had long-term follow-up (Figure 3A-B).30 We found that 107/108 (97%) of all evaluated cHLs had alterations of the PD-L1 and PD-L2 loci, including polysomy (ie, nuclei with a target:control probe ratio of 1:1 but more than 2 copies of each probe) in 5% of cases, copy gain (ie, target:control probe ratio of >1:1 but <3:1) in 56%, and amplification (ie, target:control probe ratio of ≥3:1) in 36% of tumors.30 In addition, we used dual PD-L1/PAX5 immunohistochemical staining to demonstrate copy number–dependent increased expression of PD-L1 in PAX5+ HRS cells in these tumors (Figure 3C). In this clinically annotated series of cHL patients treated with standard induction therapy, those with the highest level 9p24.1 alterations (amplification) had significantly shorter progression-free survival.30 In addition, patients with advanced stage disease were more likely to have 9p24.1 amplified tumors.30

Genetic and immunohistochemical analyses of the PD-L1 and PD-L2 loci. (A) Location and color-labeling of the BAC clones on 9p24.1 used for FISH. RP11-599H20 including PD-L1, labeled red. RP11-635N21 including PD-L2, labeled green. (B) Representative images of FISH results for the different categories. PD-L1 in red, PD-L2 in green, fused (F) signals in yellow and centromeric probe (CEP9) in aqua (A). In these images, disomy reflects 2A:2F; polysomy, 3A:3F; copy gain, 3A:6F; and amplification, 15+F. (C) PD-L1 (brown)/PAX5 (red) immunohistochemistry in the cHL cases with 9p24.1 disomy, polysomy, copy gain, and amplification from panel B. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. Reprinted with permission © (2016) American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved. Roemer, MG et al: J Clin Oncol Vol. 34 (23), 2016 2690-7.

Genetic and immunohistochemical analyses of the PD-L1 and PD-L2 loci. (A) Location and color-labeling of the BAC clones on 9p24.1 used for FISH. RP11-599H20 including PD-L1, labeled red. RP11-635N21 including PD-L2, labeled green. (B) Representative images of FISH results for the different categories. PD-L1 in red, PD-L2 in green, fused (F) signals in yellow and centromeric probe (CEP9) in aqua (A). In these images, disomy reflects 2A:2F; polysomy, 3A:3F; copy gain, 3A:6F; and amplification, 15+F. (C) PD-L1 (brown)/PAX5 (red) immunohistochemistry in the cHL cases with 9p24.1 disomy, polysomy, copy gain, and amplification from panel B. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. Reprinted with permission © (2016) American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved. Roemer, MG et al: J Clin Oncol Vol. 34 (23), 2016 2690-7.

PD-L1+ tumor-associated macrophages in cHL

Nonmalignant tumor-associated macrophages in the cHL microenvironment also express PD-L1. We recently used multiplex immunofluorescence and digital image analysis to define the relationship between normal and malignant PD-L1+ cells in the cHL tumor microenvironment.44 In these studies, we found that PD-L1+ tumor-associated macrophages physically colocalize with PD-L1+ HRS cells to form an extended immunoprotective microenvironmental niche.44 The unique topology of cHL, in which PD-L1+ tumor-associated macrophages surround PD-L1+ HRS cells, likely augments local PD-1 signaling in this disease.44

Clinical applications of PD-1 blockade in relapsed or refractory cHL

Although many cHL patients are cured with current treatment regimens, 20% to 30% fail to respond or experience a relapse after treatment.45 Therefore, there is an unmet medical need to develop alternative therapies for patients with relapsed/refractory cHL. The reversibility of T-cell coinhibitory signaling pathways exploited by cHL for immune evasion suggests that PD-1 blockade may augment antitumor immunity. As CNAs of 9p24.1 increase expression of both PD-1 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, PD-1 receptor blockade may be a better treatment strategy than selective inhibition of PD-L1.

Pilot studies and subsequent registration trials of 2 PD-1–blocking antibodies, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, in patients with multiple relapsed/refractory cHL were associated with response rates of ∼70% and long-lasting remissions in a subset of patients.46-49 These clinical trials and additional studies of PD-1 blockade at earlier time points in the therapy of cHL will be discussed in the following chapter. In the pilot study and subsequent registration trial of nivolumab in patients with relapsed/refractory cHL, HRS cells in all available biopsy specimens exhibited 9p24.1 alterations and increased expression of the PD-L1 protein46,47 ; tumor-infiltrating T cells largely expressed low/intermediate levels of PD-1.46

Mechanisms of response and resistance to PD-1 blockade

Why do some relapsed/refractory cHL patients respond well to the PD-1 blockade, but others do not? Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying response and resistance to PD-1 blockade is important for the development of optimal treatment strategies.

In certain solid tumors, PD-1 ligand expression has been associated with responsiveness to PD-1 blockade.33 In cHLs, in which there is a genetic basis for PD-1 ligand overexpression and almost all tumors are PD-L1+, the range of 9p24.1 alterations and levels of PD-L1 protein may be more predictive for response to PD-1 blockade. In recent analyses of tumor biopsy specimens from patients with relapsed/refractory cHL treated with nivolumab, we found that patients whose tumors exhibited the lowest-level 9p24.1 alterations and PD-L1 expression were less likely to respond to PD-1 blockade.47

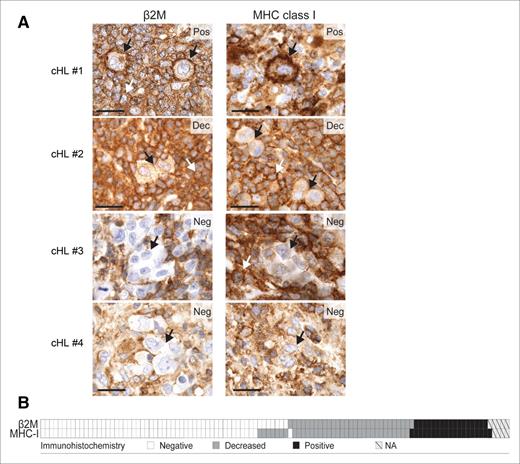

An additional potential mechanism of resistance to PD-1 blockade might be ineffective tumor antigen presentation by cell surface MHC proteins. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells recognize tumor antigens presented in the context of cell surface MHC class I proteins. MHC class I proteins are transported to the cell surface in association with β2 microglobulin (β2M). Previous reports suggest that cell surface MHC class I expression may be perturbed by inactivating mutations or copy loss of B2M in cHL.22 For these reasons, we recently evaluated β2M and MHC class I expression in the aforementioned clinically annotated cHL series; 79% of cHLs had decreased/absent HRS cell surface expression of β2M and MHC class I (Figure 4A-B).50 In this series, there was a highly significant association between the levels of β2M and MHC class I expression in individual cHLs (Figure 4B, P < .001).50 These data support the hypothesis that alterations of β2M may be a major mechanism of deficient MHC class I expression in cHL. Others have also described deficient MHC class I expression in cHL.51

β2M, MHC class I, and MHC class II expression in cHL patients. (A) β2M and MHC class I immunohistochemical staining in 4 representative cHL patients: #1, positive for both markers (Pos); #2, decreased for both markers (Dec); #3 and #4, negative for both markers (Neg). Individual HRS cells are depicted with a black arrow. The white arrows indicate expression on surrounding, nonmalignant inflammatory cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Heat map representing the distribution of β2M and MHC class I (MHC-I) expression in the 108 cHL patients. White, negative; gray, decreased; black, positive; hatched, not assessable (NA). Reprinted with permission from Cancer Immunology Research 2016; 4: 910.

β2M, MHC class I, and MHC class II expression in cHL patients. (A) β2M and MHC class I immunohistochemical staining in 4 representative cHL patients: #1, positive for both markers (Pos); #2, decreased for both markers (Dec); #3 and #4, negative for both markers (Neg). Individual HRS cells are depicted with a black arrow. The white arrows indicate expression on surrounding, nonmalignant inflammatory cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Heat map representing the distribution of β2M and MHC class I (MHC-I) expression in the 108 cHL patients. White, negative; gray, decreased; black, positive; hatched, not assessable (NA). Reprinted with permission from Cancer Immunology Research 2016; 4: 910.

The paucity of β2M/MHC class I expression on HRS cells suggests that there may be alternative mechanisms of action of PD-1 blockade in cHL beyond CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Despite the focus on CD8+ T-cell–mediated mechanisms of PD-1 blockade,40,52,53 recent studies also suggest a role for MHC class II–associated antigen presentation and CD4+ infiltrating T cells in certain solid tumors54 and define tumor neoantigens that are largely recognized by CD4+ T cells.55,56 These observations are particularly interesting given the predominance of CD4+ T cells in cHL inflammatory/immune cell infiltrates and the selective association of PD-L1+ HRS cells with PD-1+ CD4+ T cells.44 We anticipate that ongoing multiparametric analyses of intact cHL tumor biopsies44 and cell suspensions and assessments of tumor biopsies from cHL patients treated with PD-1 blockade will be highly informative.

Lessons for other lymphoid malignancies

The principles we elucidate for cHLs may be applicable to other lymphoid malignancies with genetic bases for PD-1 ligand expression, including primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and primary testicular lymphoma.29,57-60 Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma shares certain molecular features with cHL, including recurrent chromosome 9p24.1 alterations and copy number–dependent increased expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2.29,57 Although the genetic signature of cHL is quite different from that of primary central nervous system lymphoma and primary testicular lymphoma,58 these diseases all exhibit recurrent 9p24.1 CNAs and increased PD-1 ligand expression. Early clinical trials suggest that PD-1 blockade may also be active in these additional lymphoid malignancies.59,60

In conclusion, cHLs use complementary genetic bases of immune evasion, including PD-1 signaling, to survive within a T-cell and inflammatory cell–rich microenvironment. These features also make cHL uniquely sensitive to PD-1 blockade and establish a paradigm for the identification of PD-1–dependent lymphoid malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA161026, the Miller Family Fund, and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb to M.A.S.

Authorship

Contribution: W.R.L. and M.A.S. developed and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: W.R.L. declares no competing financial interests. M.A.S. is on the Board of Directors or an advisory committee for Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and Merck and has received research funding from BMS. Off-label drug use: none disclosed.

Correspondence: Margaret A. Shipp, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: Margaret_Shipp@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

This article was selected by the Blood and Hematology 2017 American Society of Hematology Education Program editors for concurrent submission to Blood and Hematology 2017. It is reprinted in Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017:310-316.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal