Abstract

Although the root cause of sickle cell disease is the polymerization of hemoglobin S (HbS) to form fibers that make red cells less flexible, most drugs currently being assessed in clinical trials are targeting the downstream sequelae of this primary event. Less attention has been devoted to investigation of the multiple ways in which fiber formation can be inhibited. In this article, we describe the molecular rationale for 5 distinct approaches to inhibiting polymerization and also discuss progress with the few antipolymerization drugs currently in clinical trials.

Introduction

There has been a recent explosion of interest among investigators in the hematology academic community and the pharmaceutical industry to develop new treatments for sickle cell disease, as indicated by the large number of active clinical protocols1-5 and the many talks and posters at the 58th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego, CA, in December 2016. The interest and progress in discovering new treatments for the first “molecular disease”6,7 have been fueled by multiple factors. With an appropriate sibling match, the disease can be cured in both children and adults by stem cell transplantation.8,9 Moreover, sickle cell disease is a testing ground for the exciting emerging methods of gene therapy and gene editing.10-12 Although these are potential therapies for patients in the United States, neither will be available for several decades for millions of patients in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere.13 Therefore, what is needed to treat the vast majority of patients is an affordable drug that can be taken orally. The development of hydroxyurea has been a major advance in the treatment of sickle cell disease, but it is only partially effective in preventing vaso-occlusive crises.14-16

Most of the nongenetic approaches currently being assessed in clinical trials are aimed at using drugs to ameliorate the downstream sequelae of sickle cell hemoglobin (HbS) polymerization, such as adhesion of red cells to vascular endothelium, leukocytes, and platelets, as well as inflammation, coagulation, and nitric oxide scavenging.17-21 Indeed, there is strong rationale for thorough investigation of these phenomena, and therapeutic applications are beginning to bear fruit. For example, the administration of GMI-1070, a pan-selectin inhibitor, seems to shorten the duration of acute sickle pain crises accompanied by a marked reduction in opioid use.22 Moreover, a recent randomized double-blind study found that monthly administration of a monoclonal antibody against P-selectin was effective in lowering the frequency of sickle pain crises.23 Although these therapeutic interventions do not seem to be significantly superior to hydroxyurea, they could be effective in combination. Other attempts to target downstream sequelae have not proved to be as effective.24-32

In this article, we argue that more bench research and clinical trials should be directed toward the polymerization process itself, the root cause of sickle cell pathology. The purpose of this article is to briefly describe the biochemical and biophysical basis of 5 distinct approaches to inhibit polymerization for treating sickle cell disease and to discuss their connection to the anti-polymerization drugs currently in clinical trials.

Before considering different ways of decreasing fiber formation, it is important to point out that therapeutic benefit does not require complete inhibition of HbS polymerization. The rates of oxygen binding and dissociation are so fast (milliseconds) that the fractional saturation of normal Hb during the ∼1-second duration of blood flow through the microcirculation is determined only by the oxygen pressure. Consequently, the equilibrium oxygen binding curves, which are measured on a time scale of minutes, are relevant to the physiological situation in vivo.33 In contrast, kinetics plays a critical role in sickle cell disease because the system is very far from equilibrium. For most homozygous SS disease (HbSS) red cells, the rate of polymerization in vivo is much slower than the transit time through the microcirculation, and therefore far less polymerization occurs in vivo than is observed at the same oxygen pressures at equilibrium in vitro. If polymerization were at equilibrium (ie, instantaneous relative to the transit time), the vast majority of red cells in patients with HbSS disease would contain fibers in the tissues, whereas numerous studies show that only a fraction (often quite small) of red cells in the veins contains fibers (see Mozzarelli et al34 and references therein). Moreover, at equilibrium, sickle fibers would be present in the tissues in a large fraction of red cells of patients who are compound heterozygotes for HbS and who have hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HbS/HPFH).35,36 The red cells of these patients have a pancellular distribution of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and “have symptoms of neither sickle cell disease nor hemolytic anemia.”37

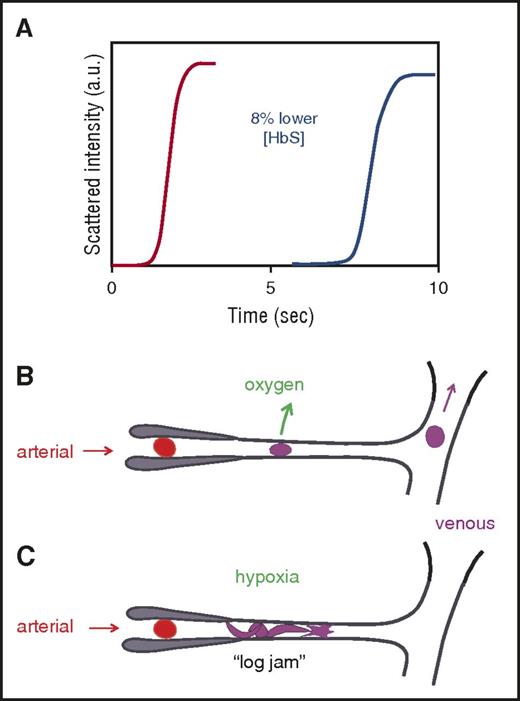

What makes HbSS disease survivable and HbS/HPFH benign is the unusual kinetics of polymerization, with a marked delay period before fibers appear38 that allows most cells to escape the small vessels of the tissues before fibers start to form (Figure 1).34,39 Because the delay time is extraordinarily sensitive to oxygen pressure and intracellular Hb concentration, even small degrees of polymerization inhibition can produce large increases in the delay time, allowing many more cells to escape the tissues without sickling.44 Moreover, transient changes in the delay time probably contribute importantly to the episodic nature and unpredictability of sickle cell crises.45 Thus, the probability of sickling in the microcirculation is decreased if the delay time is increased43,44 or if the transit time through the microcirculation is decreased, which is the therapeutic rationale for reducing adhesion of blood cells to the vascular endothelium.17-19,21

Connection between kinetics and pathophysiology. (A) Schematic of kinetic progress curve for polymerization occurring on the seconds time scale measured by light scattering due to fiber formation. Before the appearance of fibers, there is a delay (lag phase).38 The delay time is extraordinarily sensitive to HbS concentration, depending on the 30th power of the concentration.38,40 Such a large exponent means that a decrease of only 8% in the HbS concentration increases the delay time 10-fold. (B) Schematic of microcirculation: arteriole, capillary, and venule. The vast majority of cells escape the microcirculation before fibers form and cause cellular distortion (sickling).34,41 (C) Schematic of vaso-occlusion. If the delay time is shorter than the transit time (or fibers have not completely dissolved upon oxygenation in the lungs42 and can grow without a delay34,43 ), fibers form within the small vessels and can cause vaso-occlusion. In this graphic, factors that slow the transit of red cells through the microcirculation, such as increased adherence to the vascular endothelium by damaged red cells or increased leukocytes associated with infection will increase the probability of vaso-occlusion. a.u., arbitrary units.

Connection between kinetics and pathophysiology. (A) Schematic of kinetic progress curve for polymerization occurring on the seconds time scale measured by light scattering due to fiber formation. Before the appearance of fibers, there is a delay (lag phase).38 The delay time is extraordinarily sensitive to HbS concentration, depending on the 30th power of the concentration.38,40 Such a large exponent means that a decrease of only 8% in the HbS concentration increases the delay time 10-fold. (B) Schematic of microcirculation: arteriole, capillary, and venule. The vast majority of cells escape the microcirculation before fibers form and cause cellular distortion (sickling).34,41 (C) Schematic of vaso-occlusion. If the delay time is shorter than the transit time (or fibers have not completely dissolved upon oxygenation in the lungs42 and can grow without a delay34,43 ), fibers form within the small vessels and can cause vaso-occlusion. In this graphic, factors that slow the transit of red cells through the microcirculation, such as increased adherence to the vascular endothelium by damaged red cells or increased leukocytes associated with infection will increase the probability of vaso-occlusion. a.u., arbitrary units.

Five approaches to inhibiting HbS polymerization

1. Block intermolecular contacts in the sickle fiber

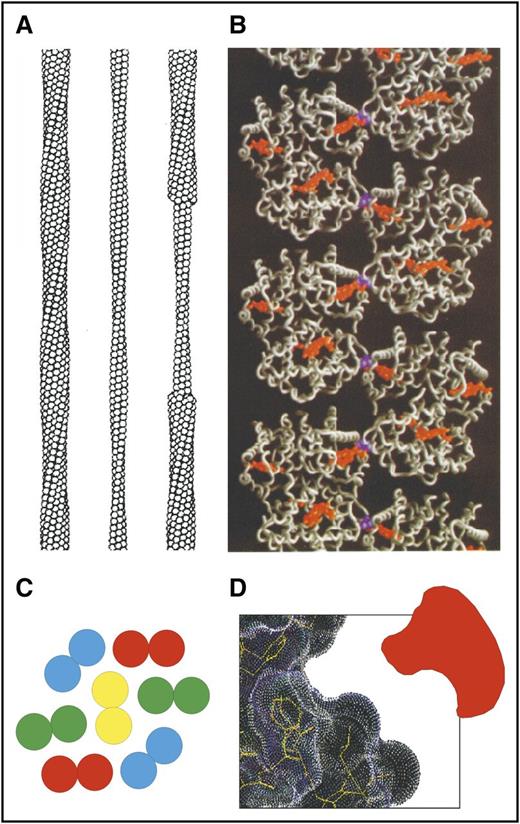

One of the important early milestones in sickle cell research was the construction of a detailed molecular model of the fiber structure (Figure 2). The structure is based on image reconstruction of transmission electron micrographs (Figure 2A),46 the X-ray structure of deoxy-HbS47 (Figure 2B), and the determination of residues that participate in an intermolecular contact from polymerization studies on mixtures of HbS with other naturally occurring Hb’s containing mutated residues on the molecular surface.48,49 The fiber (21 nm in diameter) is constructed of 14 strands that consist of 7 helically twisted strand pairs found in the X-ray structure of deoxy-HbS (Figure 2C). The polymerization studies of mixtures positioned the double strands in the fiber (determined by X-ray) to define the inter double-strand contacts.

Sickle fiber structure. (A) Low-resolution structure of 14-stranded solid fiber determined by electron microscopy.46 Each HbS tetramer is represented as a sphere. (B) Atomic structure of deoxy-HbS determined by X-ray crystallography47 showing that 1 of the 2 β6 valines (purple) in each tetramer makes an intermolecular contact with an adjacent strand close to the pocket containing the hemes (orange). (C) Cross-section of sickle fiber composed of 7 double strands. (D) Cartoon of small molecule inhibitor that could fit into the shallow acceptor site for the β6 valine.

Sickle fiber structure. (A) Low-resolution structure of 14-stranded solid fiber determined by electron microscopy.46 Each HbS tetramer is represented as a sphere. (B) Atomic structure of deoxy-HbS determined by X-ray crystallography47 showing that 1 of the 2 β6 valines (purple) in each tetramer makes an intermolecular contact with an adjacent strand close to the pocket containing the hemes (orange). (C) Cross-section of sickle fiber composed of 7 double strands. (D) Cartoon of small molecule inhibitor that could fit into the shallow acceptor site for the β6 valine.

A common approach to drug development is to identify a protein target and screen compounds that bind tightly to a specific site on the protein, such as the active or, more recently, the allosteric site of an enzyme. The analogous approach for treating sickle cell disease would be to find a small molecule that has a high affinity for a site on the surface of the HbS molecule that is involved in an intermolecular contact in the fiber (see Eaton et al44 for a complete list of contact sites). The problem in using this approach for sickle cell disease is threefold. First, the drug must have a high degree of specificity for binding to HbS. Second, there is almost 1 pound of HbS in the average patient with HbSS disease, so unless the binding is extremely strong, as in a covalent bond, a very large amount of drug would be required. The third concern is that the surface of the Hb molecule is smooth, that is, there are no residues involved in an intermolecular contact available for stereospecific covalent attachment of an inhibitor, and there are no apparent deep clefts or crevices that would be required for tight, noncovalent binding (Figure 2D). However, transient openings in the structure for drug targeting might be discovered by using all-atom molecular dynamics simulations, a method currently being used to find binding sites for drug targeting that are not obvious from static X-ray structures.50 Consequently, although it is much more challenging than the more common empirical drug targeting, this approach should not be discounted.

2. Induce HbF synthesis

The symptoms of sickle cell disease do not appear until several months after birth when most of the HbF is replaced by HbS. As mentioned previously, the compound heterozygous condition of sickle cell disease with pancellular persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HbS/HPFH) is a relatively benign condition. Importantly, in HbS/HPFH, the HbF is homogeneously distributed. These F cells all contain about 30% HbF and 70% HbS.37 In contrast, in HbSS disease, HbF is heterogeneously distributed in about 35% of the F cells with no detectable HbF in the remaining 65% of the cells.51 After hydroxyurea therapy at maximum tolerated doses, the fraction of F cells increases to nearly 50% whereas the fraction of HbF increases even more. Thus hydroxyurea therapy results in an increase in HbF per F cell. The drug would be more effective if the increase in HbF were distributed among a greater fraction of red cells.52 The focus of current research in this area, therefore, is to induce HbF synthesis in as many red cells as possible.53 One promising approach is the selective inhibition of the transcription factor BC11A, which dramatically increases the expression of γ globin.54,55

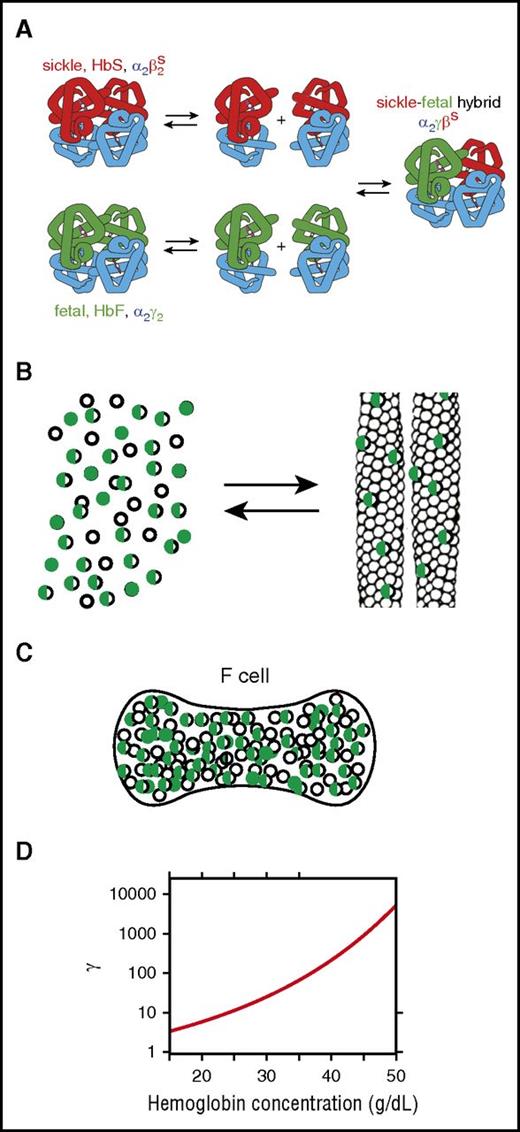

Because of the enormous sensitivity of the kinetics of polymerization to the concentration of the HbS homotetramer α2βS2, the beneficial effect of HbF results primarily from a decrease in the intracellular concentration of α2βS2.56 However, this inhibitory effect is quite complex35 (Figure 3). Dissociation of tetramers into αβ dimers and random re-association results in a binomial distribution of tetramers, further reducing the concentration of the α2βS2 homotetramer57 (Figure 3A). A mixture of 70% HbS and 30% HbF, for example, contains 3 tetramers with a binomial distribution (49% α2βS2, 9% α2γ2, and 42% α2γβS).

Mechanism of inhibition of polymerization by HbF. (A) Dissociation of tetramers into dimers and reassociation in mixtures of HbS and HbF result in 3 tetramers in a binomial distribution, thereby further lowering the fraction of the HbS homotetramer (α2βS2).57 (B) Cartoon of polymerization equilibrium in HbS-HbF mixture. As in a crystallization reaction, Hb tetramers are present in 2 phases: the solution phase (left) or the fiber phase (right). The fibers that form in these mixtures are primarily composed of the HbS homotetramers, but there is also some copolymerization of hybrid tetramers (α2βSγ) (half-green, half-empty circles).35,58 (C) Cartoon of F cell with 30% HbF and 70% HbS. The excluded volume effect of the non-copolymerizing α2γ2 tetramer (green-filled circles) and partially copolymerizing tetramer α2βSγ (half-green, half-empty circles) increases the activity of the polymerizing α2βS2 homotetramer (empty circles). (D) Activity coefficient (γ) as a function of total Hb concentration. The dimensionless activity coefficient is the factor that multiplies the measured concentration (ie, moles per liter or grams per deciliter) to obtain the activity, which is the thermodynamically effective concentration.59

Mechanism of inhibition of polymerization by HbF. (A) Dissociation of tetramers into dimers and reassociation in mixtures of HbS and HbF result in 3 tetramers in a binomial distribution, thereby further lowering the fraction of the HbS homotetramer (α2βS2).57 (B) Cartoon of polymerization equilibrium in HbS-HbF mixture. As in a crystallization reaction, Hb tetramers are present in 2 phases: the solution phase (left) or the fiber phase (right). The fibers that form in these mixtures are primarily composed of the HbS homotetramers, but there is also some copolymerization of hybrid tetramers (α2βSγ) (half-green, half-empty circles).35,58 (C) Cartoon of F cell with 30% HbF and 70% HbS. The excluded volume effect of the non-copolymerizing α2γ2 tetramer (green-filled circles) and partially copolymerizing tetramer α2βSγ (half-green, half-empty circles) increases the activity of the polymerizing α2βS2 homotetramer (empty circles). (D) Activity coefficient (γ) as a function of total Hb concentration. The dimensionless activity coefficient is the factor that multiplies the measured concentration (ie, moles per liter or grams per deciliter) to obtain the activity, which is the thermodynamically effective concentration.59

Two additional effects must be considered in addition to tetramer-dimer dissociation and re-association. One is copolymerization of the α2γβS hybrid tetramer (Figure 3B),58,60 which can enter the fiber but to a much lesser extent than the α2βS2 homotetramer or even the α2βSβA hybrid tetramer because in the γ subunit, threonine at position 87 is replaced by a glutamine, which forms a much less favorable critically important intermolecular lateral contact with β6 valine (Figure 2B). The second effect of the decrease in concentration of α2βS2 is the large nonideality in the concentrated HbS solution within the red cell. The thermodynamically effective concentration of α2βS2, called the activity, is not the measured concentration in moles or grams per unit volume, but rather the concentration multiplied by a correction factor, the activity coefficient (γ) (Figure 3D). The activity coefficient accounts for the fact that the non-copolymerizing tetramers take up space in the solution and decrease the volume accessible to the polymerizing tetramers. This so-called “excluded volume” effect is extremely large and must be considered in all thermodynamic and kinetic descriptions of polymerization.59,61-64 The activity at a concentration of 35 g/dL, a typical mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), for example, is almost 100 times greater than the measured concentration. The net result of this effect is that the activity of α2βS2 in the solution phase at equilibrium is increased, making the decrease in the concentration of the α2βS2 tetramer by HbF less effective in increasing the delay time than by simply increasing red cell volume by means of osmotic or ionophoric dilution discussed below.

3. Increase oxygen affinity

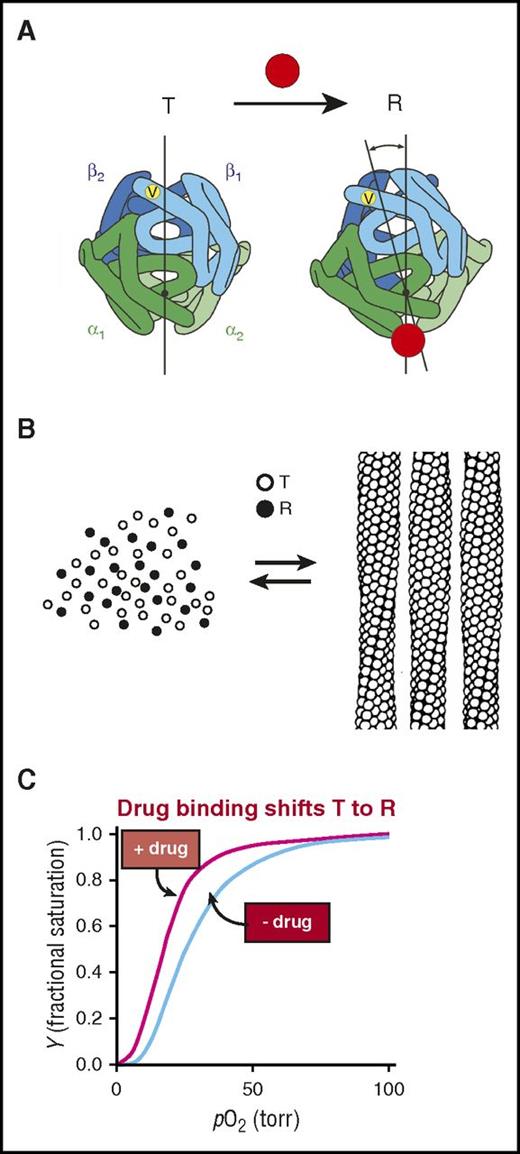

The results of studies on the control of polymerization by oxygen can be explained by applying the famous 2-state allosteric Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model (Figure 4).65,66 According to the MWC model, there is an equilibrium between a low oxygen affinity arrangement of the 4 subunits of fully deoxygenated hemoglobin, called the T quaternary structure, and a high affinity arrangement of fully oxygenated Hb, called the R quaternary structure (Figure 4A). Solubility measurements of concentrated solutions of HbS as a function of the saturation of Hb with oxygen in the solution phase can be almost quantitatively explained by not allowing the R quaternary structure to enter the fiber. (The solubility is the concentration of Hb in the solution phase and corresponds to the measured concentration of Hb in the supernatant after sedimenting the fibers in an ultracentrifuge. Solubility is an accurate measure of the stability of the fiber: the lower the solubility, the more stable the fiber67,68 ). Moreover, the sickle fiber binds oxygen with an affinity that is very similar to the T quaternary structure in the crystal.69,70 These results are consistent with structural analysis, which shows that the arrangement of the subunits in the R structure produces many steric clashes71 that preclude incorporation into the T-containing fiber.

Mechanism of polymerization inhibition by increasing oxygen affinity. (A) Hemoglobin exists in a rapidly reversible equilibrium between low- and high-affinity quaternary conformations, called T and R, respectively.65,66 They differ primarily by an ∼15° relative rotation of αβ dimers. Location of β6 valine is shown as a yellow dot on the surface of the molecule. Preferential binding of a small molecule such as a drug (red circle) to R shifts the quaternary equilibrium toward R. (B) Cartoon of polymerization equilibrium. Only the T quaternary structure (empty circles) enters the fiber. R quaternary conformations (filled circles) are completely excluded.69 (C) Oxygen binding curves. Preferential binding of a drug to the R quaternary structure causes a left shift (increased oxygen affinity).

Mechanism of polymerization inhibition by increasing oxygen affinity. (A) Hemoglobin exists in a rapidly reversible equilibrium between low- and high-affinity quaternary conformations, called T and R, respectively.65,66 They differ primarily by an ∼15° relative rotation of αβ dimers. Location of β6 valine is shown as a yellow dot on the surface of the molecule. Preferential binding of a small molecule such as a drug (red circle) to R shifts the quaternary equilibrium toward R. (B) Cartoon of polymerization equilibrium. Only the T quaternary structure (empty circles) enters the fiber. R quaternary conformations (filled circles) are completely excluded.69 (C) Oxygen binding curves. Preferential binding of a drug to the R quaternary structure causes a left shift (increased oxygen affinity).

The MWC analysis of the control of polymerization by oxygen strongly suggests that increasing oxygen affinity by shifting the T-R equilibrium toward R could be a sound way to inhibit HbS polymerization in vivo and therefore could be an effective treatment strategy. Indeed, years ago, this rationale prompted Beutler72 to increase the fraction of R HbS in a small number of sickle cell patients by induction of either methemoglobin or carboxyhemoglobin.73 He found that either intervention resulted in a significant prolongation of the life span of red blood cells. However, neither could be adapted for practical and safe long-term therapy. Current advances in drug discovery and high throughput screening offer the hope of developing small molecules that bind to R preferentially and with high specificity and would therefore be a compelling therapeutic approach.4,74 The potential downside of altering the T-R equilibrium is that the resulting left shift in the oxygen binding curve (Figure 4C) could potentially decrease oxygen delivery in a disease in which the patients already suffer from impaired blood flow and oxygen transport. The question is, what is the net effect? Reduced oxygen delivery from the left shift? Or improved oxygen delivery from decreased sickling and therefore decreased vaso-occlusive events? The physiology is too complicated to make any predictions on the basis of biophysical studies, but the results of clinical studies currently underway (discussed below) should provide the answer to this question.

4. Reduce concentration of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate

The major allosteric effector for Hb is 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG),75-77 and it has three effects on HbS polymerization. It binds in the cleft between the β subunits (Figure 5A-B) to stabilize the deoxy (T) quaternary structure and thereby decreases oxygen affinity by shifting the T-R quaternary equilibrium toward T (Figure 5C).78,79 Thus, lowering DPG concentration would increase the fraction of HbS in the nonpolymerizing R quaternary structure.80 A second effect of 2,3-DPG is that it stabilizes the fiber, as shown by a decrease in HbS solubility.81 Although the decrease in solubility is only ∼10%,81 the presence of 2,3-DPG will have a dramatic effect on the kinetics of polymerization (ie, the delay time64 ), which depends on about the 30th power of the solubility.39,64,82 Finally, decreasing 2,3-DPG concentration results in a third smaller, but therapeutically significant, increase in solubility because of an accompanying increase in the intracellular pH83 via the Gibbs-Donnan equilibrium. Over the physiologic intracellular pH range of 7.2 to 7.3, the solubility of deoxy-HbS increases significantly with increasing pH.58 Thus, reduction of red blood cell 2,3-DPG increases the delay time by 3 independent mechanisms.

Binding of 2,3-DPG to Hb. (A-B) 2,3-DPG binds in the cleft between the β (yellow) subunits of the T quaternary structure. (C) Reduction of 2,3-DPG concentration shifts the quaternary equilibrium toward R to produce a left shift in the binding curve and increases the solubility (the concentration of Hb in the solution phase [Figures 3B and 4B, left]). Both factors decrease sickling.

Binding of 2,3-DPG to Hb. (A-B) 2,3-DPG binds in the cleft between the β (yellow) subunits of the T quaternary structure. (C) Reduction of 2,3-DPG concentration shifts the quaternary equilibrium toward R to produce a left shift in the binding curve and increases the solubility (the concentration of Hb in the solution phase [Figures 3B and 4B, left]). Both factors decrease sickling.

The importance of DPG in the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease is underscored by 2 recent and highly relevant case reports. Individuals with sickle trait (HbAS), which is normally a totally benign condition, have a clinical phenotype almost as severe as HbSS disease in which they also inherit a deficiency in red blood cell pyruvate kinase, which causes a marked increase in red cell 2,3-DPG.84,85

Because 2,3-DPG plays such a critical role in potentiating HbS polymerization, there is a compelling rationale for the development of drugs that target the enzymatic pathway responsible for its remarkably high (5 mM) concentration in red cells. A number of anions stimulate the phosphatase activity of 2,3-DPG synthase, thereby lowering 2,3-DPG levels. In particular, in the presence of 0.02 mM phosphoglycolate, the dephosphorylation of 2,3-DPG is activated more than 1000-fold.86 Accordingly, adding 30 to 40 mM glycolate to a suspension of normal human red cells results in a rapid decrease in 2,3-DPG without any impact on adenosine triphosphate levels.87

5. Reduce intracellular Hb concentration

The discovery of the extraordinary sensitivity of the kinetics of fiber formation to HbS concentration38,44 led several investigators to exploit this finding in both physiological and clinical studies. The red cell behaves like a micro-osmometer with a volume that depends on the osmolality of the plasma.88 Consequently, sensitivity of the delay time to concentration suggested that therapeutic benefit could result from an increase in red cell volume sufficient to reduce the intracellular Hb concentration by as little as 10%.89 An early unblinded, limited clinical study did in fact report that lowering plasma osmolarity via induction of hyponatremia reduced the frequency of pain crises.90 Although maintenance of a sustained low-sodium diet is impractical, an important result of this study was that red cells could be swollen without the serious side effects that might result from osmotic effects on other cells.90

Reduction of intracellular Hb concentration is commonly encountered in patients who develop iron deficiency. In mouse models of sickle cell disease, induction of iron deficiency by suppression of intestinal expression of HIF-2α resulted in increased Hb levels accompanied by reduction in MCHC and hemolytic rate.91 In HbSS patients who have sustained blood loss as a result of either hemorrhage or iatrogenic phlebotomy sufficient to result in iron deficiency, the decrease in MCHC was accompanied by increased Hb and less hemolysis.92

When red cells sickle, damage to the membrane results in calcium influx, which triggers enhanced potassium efflux via the so-called Gardos channel. As a result, the red cell HbS concentration increases along with a marked increase in the probability of further sickling. Therefore, inhibition of this channel is a plausible therapeutic approach. Treatment with senicapoc (ICA-17043), a highly potent Gardos inhibitor, resulted in a decrease in red cell density and MCHC, increased Hb levels, and reduced hemolysis in both a sickle mouse model93 and in sickle cell patients.94 However, a phase 3 clinical study was terminated early because administration of this drug seemed to cause a slight increase in the rate of sickle pain crises.1 Although the rationale for Gardos channel inhibitors is sound, their efficacy depends on damage to the red cell membrane caused by cycles of cell sickling and unsickling from HbS polymerization and depolymerization.

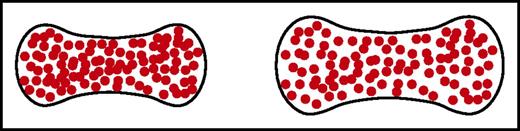

Another approach to decreasing intracellular HbS concentration, proposed many years ago, is to use ionophores.95 These agents transport extracellular sodium ions into the red cell, accompanied by water influx to maintain osmotic equilibrium and, in doing so, swell the red cell (Figure 6). A new and sensitive sickling time assay has shown that potentially therapeutic levels of inhibition can be achieved at subnanomolar concentrations of ionophores, making increase in red cell volume a viable approach to therapy.96

Schematic of normal and swollen red cells. A small increase in red cell volume to decrease the intracellular HbS concentration dramatically increases the delay time of sickling because of its high dependence on the HbS concentration. Even a 10% increase in cell volume is predicted to have a therapeutic effect.89,96

Schematic of normal and swollen red cells. A small increase in red cell volume to decrease the intracellular HbS concentration dramatically increases the delay time of sickling because of its high dependence on the HbS concentration. Even a 10% increase in cell volume is predicted to have a therapeutic effect.89,96

Anti-polymerization drugs currently in clinical trials

The Clinical Trials Web site lists an impressive number of recent and ongoing investigations into various aspects of sickle cell disease. In a review published last year, Telen3 discussed a wide range of treatments that focus on downstream sequelae of sickle vaso-occlusion, including 5 agents that target adhesion, 7 that target inflammation, 5 that involve anticoagulants, and 6 anti-platelet agents. But that review covered fewer drugs that directly target HbS polymerization. The review does include 4 drugs that induce HbF expression, but none of them seem to offer convincing advantages over hydroxyurea.

Among the drugs listed as antisickling agents is SCD-101, a plant extract similar to Niprisan (Nix-0699). Niprisan is an ethanol-water extract from the seeds, stems, fruit, and leaves of 4 different plants, has been used among diverse populations in Nigeria, and has been reported to be effective in lowering the frequency of pain crises in sickle cell patients.97,98 Niprisan inhibits in vitro sickling and increases both the solubility and delay time of solutions of deoxy-HbS, albeit in a highly nonphysiological buffer.99 Moreover, the extract prolonged the survival of transgenic sickle mice after acute hypoxic challenge.100 A recent phase 1B dose-escalation study of 26 HbSS and HbS/β0-thalassemia patients found that SCD-101 was well tolerated and, at higher doses, it seemed to relieve chronic pain and fatigue but had no impact on Hb levels or hemolysis.101

The review by Telen3 lists only a single antisickling agent undergoing clinical trials that is known to directly modify Hb structure: 5-hydroxymethyl-furfural (Aes-103). This agent is an aldehyde that forms a reversible Schiff base linkage primarily with the N-terminal amino group of α-globin resulting in a dose-dependent increase in oxygen affinity.102-104 A significant concern with aldehyde drugs is their potential to covalently modify other cellular and plasma proteins. More recently, a polyaromatic aldehyde, GBT440, has been developed that also binds via a Schiff base to the α-globin N terminus with enhancement of oxygen affinity similar to Aes-103, but with higher specificity and at much lower concentrations.105,106 At doses that achieve an optimal increase in oxygen affinity, the partition between levels of GBT440 in the red cell and plasma is an impressive 70:1 ratio. In initial clinical trials in normal volunteers and in sickle cell patients, oral administration of GBT440 once per day is well tolerated with no significant adverse effects.107,108 Patients with HbSS disease have a dose-dependent increase in Hb levels within 2 weeks of initiating therapy accompanied by a decrease in reticulocyte count, serum nonconjugated bilirubin, and fraction of irreversibly sickled cells in peripheral blood films.107,108 Thus, GBT440 results in a significant prolongation of red cell life span in sickle cell patients. The crucial issue is the impact of this drug on the incidence and severity of pain crises and on vaso-occlusive organ damage. The efficacy and safety of the drug is now being investigated in a double-blind multicenter phase 3 study with ∼300 patients. The progress thus far with this drug offers a strong impetus to discover and evaluate other drugs that directly target HbS polymerization.

Conclusion

Because there are so many ways to inhibit HbS polymerization, there is cause for optimism. But once a polymerization inhibitor is discovered, many hurdles must be overcome, including issues of toxicity, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics, before it can be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Therefore, it would be prudent to first investigate the antipolymerization effect of the numerous molecules, in addition to drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration for which toxicity information already exists. Major therapeutic effects could result from administering a combination of drugs, which, by acting on different molecular targets, would be noncompetitive. For therapeutic strategies other than the promotion of HbF synthesis, drug discovery could be accelerated by carrying out screens with intact red cells, such as the recently reported laser photolysis method for measuring sickling times of HbAS cells.96 A method that is less technically demanding is currently under development at the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Tisdale for encouraging them to write this article, Swee Lay Thein for her careful and constructive review of the original submission, and Kenneth Ataga, Marilyn Telen, Carlo Brugnara, Hans Ackerman, and Peter Gillette for important information that was added to the revised manuscript.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: W.A.E. and H.F.B. contributed equally to writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.F.B. is a consultant for Global Blood Therapeutics Inc., the producer of GBT440. W.A.E. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: William A. Eaton, Laboratory of Chemical Physics, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Building 5, Room 104, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892-0520; e-mail: eaton@helix.nih.gov; and H. Franklin Bunn, Medicine/Hematology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis St, Boston MA 02115; e-mail: hfbunn@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

![Figure 5. Binding of 2,3-DPG to Hb. (A-B) 2,3-DPG binds in the cleft between the β (yellow) subunits of the T quaternary structure. (C) Reduction of 2,3-DPG concentration shifts the quaternary equilibrium toward R to produce a left shift in the binding curve and increases the solubility (the concentration of Hb in the solution phase [Figures 3B and 4B, left]). Both factors decrease sickling.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/20/10.1182_blood-2017-02-765891/4/m_blood765891f5.jpeg?Expires=1769827793&Signature=27DD3bkxsPPrqKUNiHYw4t~TivJXcIbYQ5~ior-1FObBGYOPbkTvLK6kijmBtcWMDis0bm-nM1mM7zoQTgR~7wM94ul7fxzbGMfGPDs2oqHr4giniKMwAOyW~D8-koQQNwaXEWZq~9g~NJJw7~bSl6t8yrqui5StmXFTjIThqoFFW7S~eC7KiS~3LAFJOr6ATaFNOZRq2HCmq~fcHZSRQD8sGaJ2Iu4W0KGBstiAbDXIJcmYJCRm4sJkxJL4tELvxCg~dJTlAFHwdkkIoi3-hqS6DLmKbN25h5IFmWTJkr0fcCMm3Zu4C3DpWF9dsTWYdr6Oek2wetO5vcCswLro6g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal