Key Points

A novel PI3Kδ inhibitor TGR-1202 synergizes with proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib by silencing c-Myc in preclinical models of lymphoma.

The unique activity of TGR-1202 as a single agent and in combination with carfilzomib is driven by an unexpected activity targeting CK1ε.

Abstract

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and the proteasome pathway are both involved in activating the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR). Because mTOR signaling is required for initiation of messenger RNA translation, we hypothesized that cotargeting the PI3K and proteasome pathways might synergistically inhibit translation of c-Myc. We found that a novel PI3K δ isoform inhibitor TGR-1202, but not the approved PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib, was highly synergistic with the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib in lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma cell lines and primary lymphoma and leukemia cells. TGR-1202 and carfilzomib (TC) synergistically inhibited phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), leading to suppression of c-Myc translation and silencing of c-Myc–dependent transcription. The synergistic cytotoxicity of TC was rescued by overexpression of eIF4E or c-Myc. TGR-1202, but not other PI3Kδ inhibitors, inhibited casein kinase-1 ε (CK1ε). Targeting CK1ε using a selective chemical inhibitor or short hairpin RNA complements the effects of idelalisib, as a single agent or in combination with carfilzomib, in repressing phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and the protein level of c-Myc. These results suggest that TGR-1202 is a dual PI3Kδ/CK1ε inhibitor, which may in part explain the clinical activity of TGR-1202 in aggressive lymphoma not found with idelalisib. Targeting CK1ε should become an integral part of therapeutic strategies targeting translation of oncogenes such as c-Myc.

Introduction

c-Myc is a master transcription factor and one of the most frequently altered genes across a vast array of human cancers including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL),1,2 and is thus an attractive therapeutic target.3 However, no direct inhibitor of c-Myc has been successfully developed for the treatment of any cancer. The c-Myc protein has a short half-life of <30 minutes,4 and the complex secondary structures in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of MYC messenger RNA (mRNA) make its translation highly dependent on the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4F (eIF4F).5,6 eIF4F exists as a complex composed of the eIF4E, eIF4A, and eIF4G subunits. eIF4E can be sequestered by eIF4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), which acts as a “brake” for initiation of mRNA translation.7 Hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1, caused by upstream signals such as mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1), leads to release of eIF4E from 4E-BP1, assembly of the eIF4F complex, and robust mRNA translation.8-10 In keeping with these data, mTORC1 and dual mTORC1/mTORC2 inhibitors have been found to cause varied degrees of inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and translation initiation for tumor-promoting genes.11-17 However, the therapeutic effects of mTOR inhibition in c-Myc–driven cancer remain poorly understood.

A number of mTORC1 inhibitors have been approved for renal cell cancer, but they demonstrate limited activity in other cancers including DLBCL. The dual mTORC1/mTORC2 inhibitor MLN0128 was recently reported to exhibit no activity in lymphoma.14 These results suggest that most cancers, including lymphoma, likely use multiple signaling pathways to ensure robust translation, and therefore are able to bypass translational downregulation caused by mTOR inhibitors. As an example, casein kinase-1 ε (CK1ε) activates mRNA translation through phosphorylating 4E-BP1 at residues distinct from those responsive to mTOR.18 PI3K is also involved in phosphorylating 4E-BP1 independently of mTORC1.19 Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that the proteasome system is involved in the activation of mTORC1,20,21 presumably through regulating the intracellular pool of amino acids.22,23 Collectively, these data suggest that phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 orchestrates multiple upstream signals required for optimal translation initiation for dynamic proteins in high demand, such as c-Myc. We hypothesized that modulating 4E-BP1 using a multitargeting approach against PI3K, the proteasome, and CK1ε could be an effective strategy for silencing of c-Myc translation in aggressive c-Myc–dependent lymphoma.

Methods

Additional methods are described in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site.

Cell culture and reagents

The cell lines were obtained from ATCC and grown in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium with 10% fetal calf serum. Carfilzomib, bortezomib, and idelalisib were purchased from Selleck. TGR-1202 was provided by TG Therapeutics.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was performed on cultured cells using the Cell Titer Glo assay, as previously described.24

Statistics

In vitro studies in cell lines were repeated twice, and those in primary patient samples and mice were done once. All cytotoxicity studies were done with triple replicas. The mean and the standard error of the mean were graphed or charted. Synergy was measured by excess over Bliss values.25 For the in vivo studies, mice were randomized to different treatment cohorts. Statistical analysis of difference in tumor volume and tumor weight among the groups was evaluated using a 1-way analysis of variance followed by individual comparisons using least significant difference (equal variance assumed). All significance testing was done at the P < .05 level, protecting the family-wise error rate.

Results

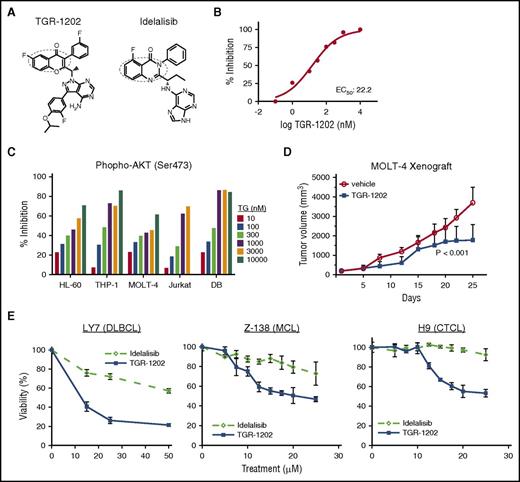

TGR-1202 is a novel selective PI3Kδ inhibitor

TGR-1202 has the core structure required for targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ (PI3Kδ), as circled in Figure 1A. In a cell-free kinase assay based on detection of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, TGR-1202 potently inhibited PI3Kδ with a half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 22.2 nM (Figure 1B). The EC50 values of TGR-1202 against the other isoforms of PI3K were substantially higher (supplemental Figure 1A), confirming TGR-1202 is a PI3Kδ inhibitor with a selectivity comparable to idelalisib,26 which is a first-in-class approved PI3Kδ inhibitor. Next, human lymphoma and leukemia cell lines known for constitutively activated AKT were treated with TGR-1202 or the vehicle control for 4 hours. TGR-1202 inhibited phosphorylated AKT at Ser473 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1C). At 1 μM, TGR-1202 reduced the phosphorylation of AKT by 43% to 87% in these cell lines. In a subcutaneous xenograft model of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) in NOD/SCID mice using the MOLT-4 cell line,27 daily oral treatment with TGR-1202 at 150 mg/kg significantly shrank the tumors by day 25 (P < .001) (Figure 1D). In select lymphoma cell lines representing DLBCL (LY7), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL; Z-138), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL; H9), TGR-1202 was more active than idelalisib inhibiting the viability of lymphoma cells, based on measurement of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in metabolically active and viable cells (Figure 1E). In other lymphoma cell lines, however, TGR-1202 and idelalisib demonstrated a comparably modest antilymphoma activity (supplemental Figure 1B).

The PI3Kδ inhibitor TGR-1202 is active in lymphomamodels. (A) The structural formulae of TGR-1202 (TG) and idelalisib with the active quinazolinone moieties circled. (B) Cell-free in vitro kinase assay of PI3Kδ in the presence of TGR-1202. (C) Cell-based assay measuring inhibition of S473 p-AKT in leukemia and lymphoma cell lines treated for 4 hours. (D) Response of the subcutaneous xenograft model of T-ALL to 3 treatments, including vehicle control and TGR-1202 (150 mg/kg) over 25 days. The xenograft was derived from the MOLT-4 cell line in NOD/SCID mice. P values were <.001 between the treatment and control groups on day 25. (E) LY7, Z-138, and H9 cells were treated by idelalisib and TGR-1202 for 24 hours (LY7) and 48 hours (Z-138 and H9) then viability was measured by Cell Titer Glo.

The PI3Kδ inhibitor TGR-1202 is active in lymphomamodels. (A) The structural formulae of TGR-1202 (TG) and idelalisib with the active quinazolinone moieties circled. (B) Cell-free in vitro kinase assay of PI3Kδ in the presence of TGR-1202. (C) Cell-based assay measuring inhibition of S473 p-AKT in leukemia and lymphoma cell lines treated for 4 hours. (D) Response of the subcutaneous xenograft model of T-ALL to 3 treatments, including vehicle control and TGR-1202 (150 mg/kg) over 25 days. The xenograft was derived from the MOLT-4 cell line in NOD/SCID mice. P values were <.001 between the treatment and control groups on day 25. (E) LY7, Z-138, and H9 cells were treated by idelalisib and TGR-1202 for 24 hours (LY7) and 48 hours (Z-138 and H9) then viability was measured by Cell Titer Glo.

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically kill blood cancer cells through disrupting the 4E-BP1–eIF4F–c-Myc axis

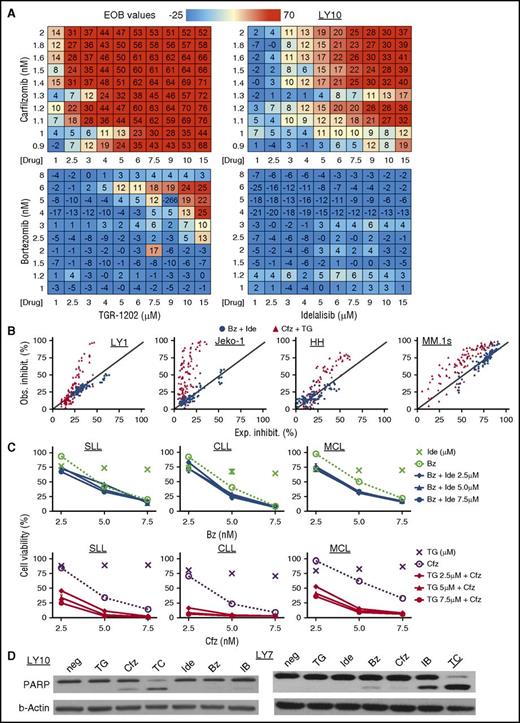

Because PI3Kδ inhibitors as single agents demonstrated only limited activity in models of aggressive lymphoma, we explored whether PI3Kδ inhibitors (TGR-1202 and idelalisib) might synergize with proteasome inhibitors (carfilzomib and bortezomib) through synergistic repression of mTOR signaling. Four combination pairs were studied in the DLBCL cell line LY10, including TGR-1202 plus carfilzomib (TC), idelalisib plus carfilzomib (IC), TGR-1202 plus bortezomib (TB), and idelalisib plus bortezomib (IB). We adopted the Bliss additivism model,25 which has been successfully used by the NCI-DREAM Drug Sensitivity Prediction Challenge, to predict drug:drug synergy. The model first calculates the expected inhibition for 2 drugs that are assumed to be additive, which is then used to calculate the excess over Bliss (EOB) value as an index of synergy. TC was clearly the most synergistic among the 4 combinations as shown by highly positive EOB values in the DLBCL cell line LY10 (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2A) and 11 other lymphoma cell lines representing DLBCL (LY1, SUDHL-4, SUDHL-2, and LY7), MCL (Jeko-1, Z138), T-ALL (PF-382, P12), CTCL (H9 and HH), and multiple myeloma (MM) (MM.1s) (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2B-C). TC was highly synergistic in primary lymphoma and leukemia cells isolated fresh from 4 patients with relapsed small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), treatment naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), treatment naive blastoid MCL with p53 deletion, and marginal zone lymphoma with chromosome 17p deletion (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 2C). The TC combination synergistically induced apoptosis, as measured by the cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and activation of caspase 3/7, in those cell lines and primary lymphoma and leukemia cells, whereas the IB and IC combinations were less active by these assays (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 2D). TC was not toxic to normal peripheral mononuclear cells (supplemental Figure 2F).

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically inhibit survival of lymphoma and leukemia cell lines and primary cells. The following drugs were studied: Bz, bortezomib; Cfz, carfilzomib; IB, Ide + Bz; Ide, idelalisib; TC, TG + Cfz; TG, TGR-1202. (A) EOB values calculated for 4 combinations of treatment in the DLBCL cell line LY10. Cells were treated for 24 hours with the indicated drugs and concentrations as single agents and in combinations. Viable cells were quantitated by the Cell-Titer Glo assay (Promega). EOB values above 0 indicate synergy. (B) Cell lines representing different hematological malignancies were treated for 48 hours. The y- and x-axes indicate the observed and expected percentage of inhibition, respectively. The expected inhibition was calculated using the Bliss model. The diagonal line indicates the line of additivism. Synergy was demonstrated by observed inhibition in excess of the expected inhibition. (C) Primary lymphoma and leukemia cells were isolated by Ficoll gradient separation from 3 patients with SLL, CLL, and MCL respectively. The SLL cells were from pleural fluid, and the CLL and MCL cells were from peripheral blood. Top panel, The results combining Ide and Bz; bottom panel, TG and Cfz. Ide and TG were given at 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μM, and their effects on viability were presented by the unconnected “×” markers. All of the other treatments were as indicated on the graphs. Viability was determined after 48 hours of treatment. (D) LY10 and LY7 cell lines were treated as indicated for 24 hours and processed for western blot. For LY7, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz were at 5 nM; for LY10, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz were at 2 nM. neg, negative control; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase.

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically inhibit survival of lymphoma and leukemia cell lines and primary cells. The following drugs were studied: Bz, bortezomib; Cfz, carfilzomib; IB, Ide + Bz; Ide, idelalisib; TC, TG + Cfz; TG, TGR-1202. (A) EOB values calculated for 4 combinations of treatment in the DLBCL cell line LY10. Cells were treated for 24 hours with the indicated drugs and concentrations as single agents and in combinations. Viable cells were quantitated by the Cell-Titer Glo assay (Promega). EOB values above 0 indicate synergy. (B) Cell lines representing different hematological malignancies were treated for 48 hours. The y- and x-axes indicate the observed and expected percentage of inhibition, respectively. The expected inhibition was calculated using the Bliss model. The diagonal line indicates the line of additivism. Synergy was demonstrated by observed inhibition in excess of the expected inhibition. (C) Primary lymphoma and leukemia cells were isolated by Ficoll gradient separation from 3 patients with SLL, CLL, and MCL respectively. The SLL cells were from pleural fluid, and the CLL and MCL cells were from peripheral blood. Top panel, The results combining Ide and Bz; bottom panel, TG and Cfz. Ide and TG were given at 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μM, and their effects on viability were presented by the unconnected “×” markers. All of the other treatments were as indicated on the graphs. Viability was determined after 48 hours of treatment. (D) LY10 and LY7 cell lines were treated as indicated for 24 hours and processed for western blot. For LY7, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz were at 5 nM; for LY10, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz were at 2 nM. neg, negative control; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase.

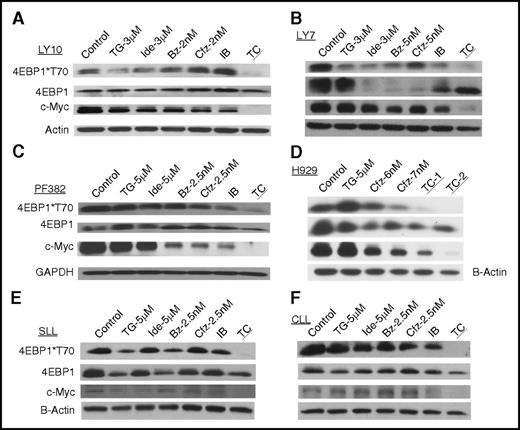

Next, we investigated the combinations described in the previous paragraph and single agents for their differential effects on mTOR signaling, focusing on the mTORC1 substrate 4E-BP1 and a further downstream event, namely translation of c-Myc. The highly synergistic TC combination, but not IB or single agents, potently inhibited phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and the protein level of c-Myc in cell lines representing DLBCL (LY10 and LY7), T-ALL (PF382), MM (H929), as well as primary SLL and CLL cells (Figure 3).

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically disrupt the 4E-BP1–eIF4F–c-Myc axis. Cell lines, including (A) LY10, (B) LY7, (C) PF382, and (D) H929, and primary cancer cells from patients with (E) SLL and (F) CLL were treated by TG, Ide, Cfz, Bz, and their combinations as indicated for 24 hours. In the H929 cell line, TC-1 and TC-2 indicate TGR at 5 μM in combination with carfilzomib at 6 and 7 nM, respectively. Cell were harvested and processed for western blot analysis using the antibodies against 4E-BP1, c-Myc, β-actin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically disrupt the 4E-BP1–eIF4F–c-Myc axis. Cell lines, including (A) LY10, (B) LY7, (C) PF382, and (D) H929, and primary cancer cells from patients with (E) SLL and (F) CLL were treated by TG, Ide, Cfz, Bz, and their combinations as indicated for 24 hours. In the H929 cell line, TC-1 and TC-2 indicate TGR at 5 μM in combination with carfilzomib at 6 and 7 nM, respectively. Cell were harvested and processed for western blot analysis using the antibodies against 4E-BP1, c-Myc, β-actin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

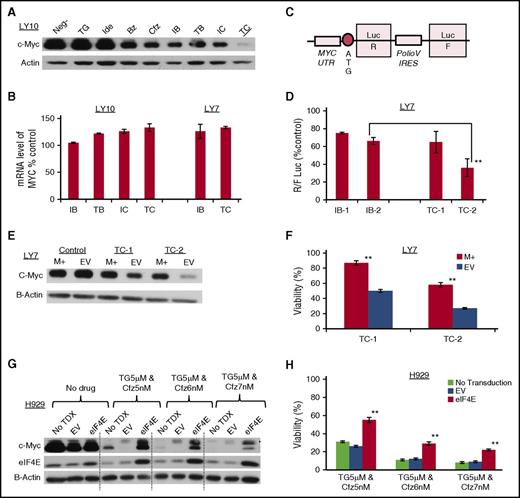

The reduction of the c-Myc protein level by TC in the cell lines described in the previous paragraphs and primary lymphoma cells was unlikely due to increased degradation of c-Myc because carfilzomib is a potent proteasome inhibitor, but rather could be due to inhibition of transcription or translation. Although the IB, TB, and IC combinations moderately reduced the protein level of c-Myc, TC markedly inhibited the expression of c-Myc in the LY10 cells (Figure 4A). Because none of the combinations decreased the mRNA level of c-Myc in LY10 or LY7 (Figure 4B), TC most likely reduced c-Myc protein level by inhibiting its translation. To further prove this hypothesis, we designed a bicistronic luciferase reporter (Figure 4C). Translation of Renilla luciferase (LucR) is regulated by the 5′ UTR of c-MYC and is dependent on eIF4F. In contrast, translation of firefly luciferase (LucF) is not eIF4F dependent as it has the Polio virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES). The relative efficiency of cap-dependent translation downstream of the 5′ UTR of c-MYC is measured by the ratio of LucR/LucF. The plasmid did transduce LY7 efficiently, but did not transfect LY10 and a number of other DLBCL cell lines. Figure 4D demonstrates that TC was significantly more potent than IB in LY7 in reducing the R:F Luc ratio (P = .0013), confirming c-Myc translation as a mechanistic target of TC.

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically inhibits translation of c-Myc in lymphoma and myeloma cell lines. The following drugs were used: TG, Ide, Bz, Cfz, IB, TB, IC, TC. (A-B) Levels of c-Myc protein (A) and mRNA (B) in LY10 and LY7 cells treated as indicated for 24 hours. For LY10, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz at 2 nM; for LY7, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz at 5 nM. (C) Schema of a bicistronic luciferase reporter for the translation of c-Myc. IRES, IRES of polio virus; UTR, UTR of c-Myc. (D) Results of the luciferase assay using the bicistronic reporter from panel C. LY7 stably expressing the reporter was treated as indicated for 24 hours. IB-1 and IB-2, Ide 3 μM and 5 μM, respectively, plus Bz 5 nM; TC-1 and TC-2, TG 3 μM and 5 μM, respectively, plus Cfz 5 nM. R:F Luc ratio from the treatment groups was calculated as a percentage of the untreated control, and represents the efficiency of eIF4F cap-dependent translation regulated at the endogenous 5′ UTR of c-Myc. The difference between the TC2 and IB2 treatments was statistically significant; **P of .0013. (E-F) LY7 cells stably transfected with a c-Myc–expressing plasmid (M+) or an EV were treated for 24 hours as indicated. The complementary DNA of c-Myc does not contain the endogenous 5′ UTR. TC-1 and TC-2, TG 3 μM and 5 μM, respectively, plus Cfz 5 nM. Cells were then processed for western blot (E) or Cell Titer Glo to determine viability (F). The difference of viability between the M+ and EV samples was statistically significant; **P < .001. (G-H) The myeloma cell line H929 was stably transduced with an eIF4E-overexpressing plasmid (eIF4E) by lentiviral transduction, or with the corresponding EV. These cells and the untransduced control (No TDX) cells were treated for 24 hours and assessed by western blot (G) and Cell-Titer Glo (H). The difference between the eIF4E and EV samples was statistically significant; **P < .001.

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib synergistically inhibits translation of c-Myc in lymphoma and myeloma cell lines. The following drugs were used: TG, Ide, Bz, Cfz, IB, TB, IC, TC. (A-B) Levels of c-Myc protein (A) and mRNA (B) in LY10 and LY7 cells treated as indicated for 24 hours. For LY10, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz at 2 nM; for LY7, TG and Ide were at 3 μM, and Bz and Cfz at 5 nM. (C) Schema of a bicistronic luciferase reporter for the translation of c-Myc. IRES, IRES of polio virus; UTR, UTR of c-Myc. (D) Results of the luciferase assay using the bicistronic reporter from panel C. LY7 stably expressing the reporter was treated as indicated for 24 hours. IB-1 and IB-2, Ide 3 μM and 5 μM, respectively, plus Bz 5 nM; TC-1 and TC-2, TG 3 μM and 5 μM, respectively, plus Cfz 5 nM. R:F Luc ratio from the treatment groups was calculated as a percentage of the untreated control, and represents the efficiency of eIF4F cap-dependent translation regulated at the endogenous 5′ UTR of c-Myc. The difference between the TC2 and IB2 treatments was statistically significant; **P of .0013. (E-F) LY7 cells stably transfected with a c-Myc–expressing plasmid (M+) or an EV were treated for 24 hours as indicated. The complementary DNA of c-Myc does not contain the endogenous 5′ UTR. TC-1 and TC-2, TG 3 μM and 5 μM, respectively, plus Cfz 5 nM. Cells were then processed for western blot (E) or Cell Titer Glo to determine viability (F). The difference of viability between the M+ and EV samples was statistically significant; **P < .001. (G-H) The myeloma cell line H929 was stably transduced with an eIF4E-overexpressing plasmid (eIF4E) by lentiviral transduction, or with the corresponding EV. These cells and the untransduced control (No TDX) cells were treated for 24 hours and assessed by western blot (G) and Cell-Titer Glo (H). The difference between the eIF4E and EV samples was statistically significant; **P < .001.

To confirm that c-Myc downregulation is a mechanistic target of the TC combination, we subcloned the MYC open reading frame without the 5′ UTR, into the pcDNA3.1(+)IRES green fluorescent protein plasmid. As a result, translation of exogenous c-Myc is expected to be less dependent on eIF4F and less prone to inhibition by 4E-BP1. As shown in Figure 4E, the c-Myc–containing plasmid (M+) mildly increased the level of c-Myc protein compared with an empty vector (EV) in the LY7 DLBCL cells not exposed to the TC treatment. When treated with TC, the level of the endogenous c-Myc protein was potently reduced in the cells transduced with the EV. In contrast, the level of c-Myc remained at a high level in the cells with the Myc+ plasmid, confirming that lack of 5′ UTR of MYC in the plasmid conveyed resistance to translational downregulation of MYC by TC. Figure 4F demonstrates that LY7 cells with the Myc+ plasmid were significantly more resistant than those cells with the EV to TC. To investigate whether sequestering of eIF4E by hypophosphorylated 4E-BP1 was a potential mechanism of action by TC, we subcloned the complementary DNA of eIF4E into the pCDH-GFP vector. For poorly understood reasons, the eIF4E plasmid was toxic to the DLBCL cell line LY7. We therefore stably transduced this plasmid and a control EV into the myeloma cell line H929, which has a well-characterized chromosomal translocation involving c-Myc.28 Figure 4G demonstrated that in H929 cells untreated with TC, the eIF4E plasmid produced slightly more eIF4E and c-Myc than the EV. In H929 cells treated with TC, the eIF4E plasmid produced substantially more eIF4E and c-Myc proteins than the EV. Cells transfected with the eIF4E plasmid were significantly more resistant to TC than cells with the EV (Figure 4H). Collectively, these results indicate that the mechanism of the remarkable synergism observed with the TC combination is due to inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and consequently downregulation of c-Myc translation.

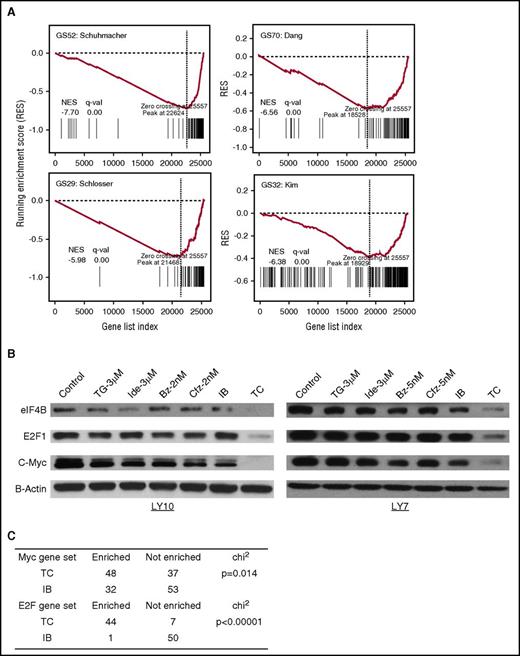

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib in combination specifically silence the c-Myc transcription program

To investigate the effects of TC on the c-Myc transcription program, gene expression profiling was performed by RNA sequencing in the DLBCL LY10 cells treated by the vehicle control, TGR-1202, idelalisib, carfilzomib, bortezomib, and the 4 combinations including TC, TB, IC, and IB for 24 hours. We calculated fold change for each gene and the P value in the combinations vs each of the single-drug exposures. Next, we combined the 2 P values to calculate a combined Z score, which were used to rank list the genes according to their upregulation or downregulation at the transcriptional level by the combinations. We then performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to evaluate the enrichment of c-Myc target genes using the annotated gene sets in the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). Figure 5A demonstrates that in the LY10 cells treated by TC, the running enrichment score (RES) of 4 “canonical” Myc target gene sets (GS52, GS70, GS29, and GS32) reached their peak RES scores at the end of the gene list ranked from most upregulated to most downregulated, with normalized enrichment score (NES) < 0 and false discovery rate (FDR) q value (q-val) = 0. In contrast, most unrelated gene sets have higher NES and/or FDR values in the TC treated sample (supplemental Figure 3A). We independently validated that 2 of the c-Myc target genes, eIF4B and E2F1, were markedly reduced by the TC combination but not by any single agents or the IB combination in the DLBCL cells LY10 and LY7 (Figure 5B). In agreement, E2F gene sets (GS43, GS38, and GS22) were also enriched among the downregulated genes (NES < 0 and FDR q-val = 0) by TC more than any other combination treatments (supplemental Figure 3B). We conducted GSEA on all the Myc and E2F target gene sets, and found that the number of c-Myc and E2F1 gene sets downregulated by TC was significantly higher than those affected by IB (P = .014 for Myc and P < .00001 for E2F) (Figure 5C; supplemental Tables 1-2). Collectively, these results demonstrate that TGR-1202 and carfilzomib in combination synergistically and selectively silence the c-Myc and E2F transcription programs.

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib inhibits c-Myc–dependent gene transcription. (A) GSEA of c-Myc target genes in LY10 cells treated by the TC combination. The x-axis represents the listed genes ranked from most upregulated to most downregulated. The y-axis indicates RESs. All the 4 gene sets reached their peak RES score at the end of ranked gene list, indicating that the drug combination of TG and Cfz exhibits a negative effect on the transcription of c-Myc targets. (B) LY10 and LY7 cells were treated as indicated for 24 hours then processed for western blot against 2 known targets of c-Myc, namely eIF4B and E2F1. (C) The χ2 test was performed to compare Myc and E2F1 gene sets enriched and not enriched for transcriptional downregulation in cells treated by the TC and IB drug combinations. GS29, Schlosser_Myc_Targets; GS32, Kim_Myc_Targets; GS52, Schuhmacher_Myc_Targets; GS70, Dang_Regulated_By_Myc.

TGR-1202 and carfilzomib inhibits c-Myc–dependent gene transcription. (A) GSEA of c-Myc target genes in LY10 cells treated by the TC combination. The x-axis represents the listed genes ranked from most upregulated to most downregulated. The y-axis indicates RESs. All the 4 gene sets reached their peak RES score at the end of ranked gene list, indicating that the drug combination of TG and Cfz exhibits a negative effect on the transcription of c-Myc targets. (B) LY10 and LY7 cells were treated as indicated for 24 hours then processed for western blot against 2 known targets of c-Myc, namely eIF4B and E2F1. (C) The χ2 test was performed to compare Myc and E2F1 gene sets enriched and not enriched for transcriptional downregulation in cells treated by the TC and IB drug combinations. GS29, Schlosser_Myc_Targets; GS32, Kim_Myc_Targets; GS52, Schuhmacher_Myc_Targets; GS70, Dang_Regulated_By_Myc.

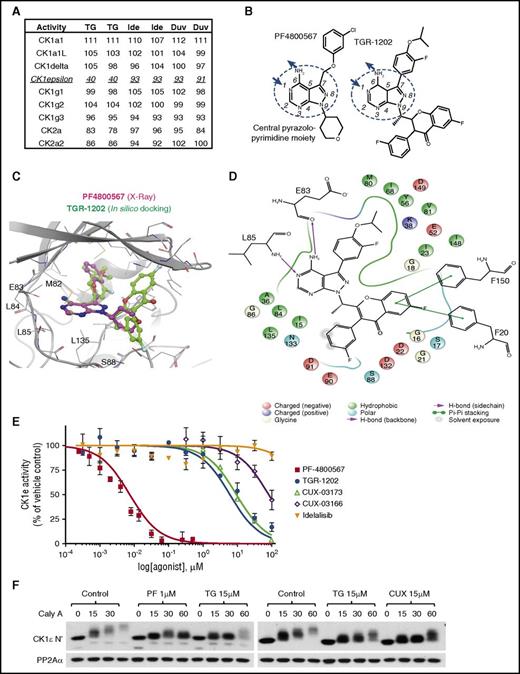

TGR-1202 demonstrates activity targeting CK1ε

To understand why TGR-1202 was consistently superior to idelalisib when combined with carfilzomib, we compared the activity of TGR-1202 with 2 other PI3Kδ inhibitors, idelalisib and duvelisib/IPI-145, on a panel of 365 wild-type protein kinases using the kinome profiling platform from Reaction Biology (Malvern, PA). The PI3Kδ inhibitors were not active against this panel of protein kinases with 1 exception: at 1 μM, TGR-1202 inhibited 60% of the activity of CK1ε, which was not observed with idelalisib or duvelisib (Figure 6A; supplemental Table 3).

TGR-1202 acts as an inhibitor of CK1ε. (A) Excerpt of kinome profiling data, showing the activity of various casein kinases when treated by 3 PI3Kδ inhibitors at the same condition of 1 μM, including TG, Ide, and duvelisib (Duv). The details are listed in supplemental Table 3. (B) Structural formulae of PF-4800567 and TGR-1202 with the CPA moiety circled, and central ring atoms numbered. The arrows denote the positions involved as hydrogen bonds donor (amine group) and acceptor (position 1). (C) Comparison of the cocrystallization of PF-4800567 and CK1ε to in silico docking of TGR-1202 in the active site binding pocket. (D) Interaction map of TGR-1202 with the active site amino acids of CK1ε with legend at the bottom. (E) Cell-free kinase activity assay of CK1ε measuring dose-activity curves of PF-4800567, TG, Ide, CUX-03173, and CUX-03166. EC50 and R2 values are listed in supplemental Figure 4F. (F) Cell-based autophosphorylation assay of CK1ε C terminus. LY7 cells were pretreated for 1 hour with the indicated drugs and then treated with the PP2A inhibitor calyculin-A (Caly A) for 0, 15, 30, and 60 minutes when lysates were collected and western blots were performed. CUX, CUX-03173; PF, PF4800567.

TGR-1202 acts as an inhibitor of CK1ε. (A) Excerpt of kinome profiling data, showing the activity of various casein kinases when treated by 3 PI3Kδ inhibitors at the same condition of 1 μM, including TG, Ide, and duvelisib (Duv). The details are listed in supplemental Table 3. (B) Structural formulae of PF-4800567 and TGR-1202 with the CPA moiety circled, and central ring atoms numbered. The arrows denote the positions involved as hydrogen bonds donor (amine group) and acceptor (position 1). (C) Comparison of the cocrystallization of PF-4800567 and CK1ε to in silico docking of TGR-1202 in the active site binding pocket. (D) Interaction map of TGR-1202 with the active site amino acids of CK1ε with legend at the bottom. (E) Cell-free kinase activity assay of CK1ε measuring dose-activity curves of PF-4800567, TG, Ide, CUX-03173, and CUX-03166. EC50 and R2 values are listed in supplemental Figure 4F. (F) Cell-based autophosphorylation assay of CK1ε C terminus. LY7 cells were pretreated for 1 hour with the indicated drugs and then treated with the PP2A inhibitor calyculin-A (Caly A) for 0, 15, 30, and 60 minutes when lysates were collected and western blots were performed. CUX, CUX-03173; PF, PF4800567.

Remarkably, TGR-1202 and the selective CK1ε inhibitor PF480056729 share a similar overall architecture with a central pyrazolopyrimidine amine (CPA) moiety substituted at the same positions 7 and 9 (Figure 6B). A previous x-ray crystallography study of PF4800567 has confirmed that the CPA moiety plays a key role in the binding of the inhibitor to CK1ε as it establishes 2 hydrogen bonds with the hinge region of CK1ε (supplemental Figure 4A).30 In this orientation, the chlorobenzene moiety of PF4800567 (substituted at position 7), occupies a hydrophobic pocket deeper in the protein (Figure 6C). In silico docking of TGR-1202 into the ATP pocket of CK1ε resulted in top scoring (best docking score, −9.3) binding modes very consistent with that of PF4800567, with the CPA moiety superposing very well and establishing the exact same hydrogen bonds (Figure 6C-D). Importantly, the favorable docking scores obtained for these virtual binding modes reveal that the hydrophobic pocket reached by the chlorobenzene moiety for PF4800567 can favorably accommodate the somewhat larger corresponding moiety in TGR-1202. In contrast, although idelalisib contains an adenine moiety that is reminiscent of the CPA moiety shared by PF4800567 and TGR-1202, the potential hydrogen bond donors and acceptors are distributed very differently (supplemental Figure 4B). Consistently, in silico docking of idelalisib fails to identify high-scoring binding modes (best docking score, −3.8) into the CK1ε ATP pocket.

Based on this structural insight, we synthesized 2 TGR-1202 analogs, CUX-03173 and CUX-03166, which differ by 1 extra methyl group on CUX-03166 (supplemental Figure 4C). Consistent with its high chemical similarity with TGR-1202, in silico docking of CUX-03173 results in a top-binding pose very close to that of TGR-1202 (supplemental Figure 4D-E). In contrast, in silico docking of CUX-03166 in CK1ε results in poses with significantly worse docking scores than CUX-03173 and TGR-1202, as the floor of the ATP-binding pocket leaves insufficient room for the methyl group on CUX-03166.

We experimentally determined the CK1ε–inhibiting activity of the previously described compounds using the ADP-Glo Kinase Assay kit and recombinant CK1ε expressed by baculovirus in Sf9 insect cells. PF4800567 was highly potent against CK1ε with an EC50 of 7.4 nM (Figure 6E; supplemental Figure 4F), consistent with the previous report.29 TGR-1202 was active against CK1ε, with an EC50 value of 6.0 μM. The EC50 for CUX-03173 was 9.4 μM. In contrast, idelalisib or CUX-03166 did not reach 50% inhibition even at 50 μM. Next, we directly tested the effects of TGR-1202 on intracellular CK1ε by examining its effect on the autophosphorylation of the CK1ε C-terminal regulatory domain.31-33 Autophosphorylation is inhibited or stimulated by CK1ε inhibitors or phosphatase inhibitors such as calyculin A, respectively. In the negative control not treated with any of the tested kinase inhibitors, calyculin A produced time-dependent autophosphorylation of CK1ε, as shown by upshifting and dimming of the CK1ε band in the DLBCL cell line LY7 (Figure 6F). In samples treated by PF4800567 (1 μM), TGR-1202 and CUX-03173 (10-25 μM) the upshifting of the CK1ε band was delayed and reduced (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 4G). Idelalisib at 25 μM remained inactive by this assay (supplemental Figure 4G). These results demonstrate that among the studied PI3Kδ inhibitors, TGR-1202 is uniquely characterized with structural features suitable for targeting CK1ε in lymphoma cells.

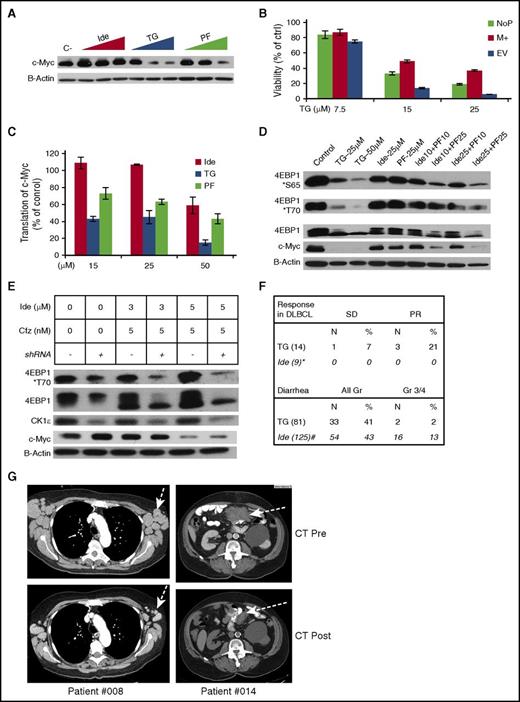

Targeting of CK1ε is required for effective inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and c-Myc translation

To establish that targeting CK1ε is required for optimal treatment of c-Myc–dependent lymphoma, we first compared the effects of the dual PI3Kδ/CK1ε inhibitor TGR-1202, selective PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib, and selective CK1ε inhibitor PF4800567 on c-Myc and 4E-BP1. Figure 7A demonstrates that, at concentrations ranging from 15 to 50 μM, TGR-1202 was more potent than idelalisib and PF4800567 at repressing the expression of c-Myc in the DLBCL cell line LY7. Importantly, lymphoma cells transduced with the c-Myc–overexpressing plasmid (M+) described in Figure 4E were significantly more resistant to TGR-1202 than the cells with the EV (Figure 7B; supplemental Figure 5A). To determine whether the reduction of c-Myc protein level by TGR-1202 was due to downregulated c-Myc translation, we performed the reporter assay as described in Figure 4C-D. The ratio of LucR:LucF was reduced by >50% by TGR-1202 at 15 μM but not by idelalisib or PF4800567 (P < .001) (Figure 7C). Interestingly, combining the selective PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib and selective CK1ε inhibitor PF4800567, both at 25 μM, reproduced the potent inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and c-Myc protein level caused by the dual PI3Kδ/CK1ε inhibitor TGR-1202 at 25 μM in LY7 cells (Figure 7D). These results indicate that cotargeting PI3Kδ and CK1ε produces synergistic inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and Myc translation.

Targeting of CK1ε is required for inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, silencing of c-Myc translation, and likely clinical activity in aggressive lymphoma. The following drugs were used: Ide, TG, PF4800567 (PF), Cfz. (A) Western blot analysis of LY7 cells treated with vehicle control (c-), and Ide, TG, and PF at 15, 25, 50 μM for 24 hours. (B) LY7 cells stably transfected with a c-Myc–overexpressing plasmid (M+) or an EV were treated at the indicated concentrations of TG for 24 hours, then processed for Cell Titer Glo to determine viability. The parental LY7 cell without plasmid transfection (NoP) served as an additional control. The protein levels of c-Myc in these samples were demonstrated in supplemental Figure 5A. (C) LY7 cells stably expressing the bicistronic reporter described in Figure 4C were treated with the indicated drugs for 24 hours. R:F Luc ratios from the treatment groups were calculated as a percentage of the untreated control, and represented the efficiency of eIF4F cap-dependent translation regulated at the endogenous 5′ UTR of c-Myc. (D) Western blot analysis of LY7 cells treated by various singles agents and combinations for 24 hours. The numbers in the combinations indicated the drug concentrations in μM. (E) Effects of CK1ε knockdown on the combination of Ide + Cfz. LY7 cells stably expressing the CK1ε targeting shRNA (shRNA+) or the parental untransduced control cells (shRNA−) were treated as indicated for 24 hours and assessed by western blot. (F) Top panel, Response to TGR-1202 as a single agent in all 14 patients with DLBCL enrolled in a phase 1 clinical study. The results of idelalisib were extracted from the publication by Westin et al.34 Bottom panel, Frequency of diarrhea in all 81 patients taking TGR-1202 in the phase 1 study. The results of idelalisib were extracted from the publication by Gopal et al.35 (G) Pre- and posttreatment images of x-ray computed tomography from 2 DLBCL patients treated with TGR-1202.

Targeting of CK1ε is required for inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, silencing of c-Myc translation, and likely clinical activity in aggressive lymphoma. The following drugs were used: Ide, TG, PF4800567 (PF), Cfz. (A) Western blot analysis of LY7 cells treated with vehicle control (c-), and Ide, TG, and PF at 15, 25, 50 μM for 24 hours. (B) LY7 cells stably transfected with a c-Myc–overexpressing plasmid (M+) or an EV were treated at the indicated concentrations of TG for 24 hours, then processed for Cell Titer Glo to determine viability. The parental LY7 cell without plasmid transfection (NoP) served as an additional control. The protein levels of c-Myc in these samples were demonstrated in supplemental Figure 5A. (C) LY7 cells stably expressing the bicistronic reporter described in Figure 4C were treated with the indicated drugs for 24 hours. R:F Luc ratios from the treatment groups were calculated as a percentage of the untreated control, and represented the efficiency of eIF4F cap-dependent translation regulated at the endogenous 5′ UTR of c-Myc. (D) Western blot analysis of LY7 cells treated by various singles agents and combinations for 24 hours. The numbers in the combinations indicated the drug concentrations in μM. (E) Effects of CK1ε knockdown on the combination of Ide + Cfz. LY7 cells stably expressing the CK1ε targeting shRNA (shRNA+) or the parental untransduced control cells (shRNA−) were treated as indicated for 24 hours and assessed by western blot. (F) Top panel, Response to TGR-1202 as a single agent in all 14 patients with DLBCL enrolled in a phase 1 clinical study. The results of idelalisib were extracted from the publication by Westin et al.34 Bottom panel, Frequency of diarrhea in all 81 patients taking TGR-1202 in the phase 1 study. The results of idelalisib were extracted from the publication by Gopal et al.35 (G) Pre- and posttreatment images of x-ray computed tomography from 2 DLBCL patients treated with TGR-1202.

Next, we investigated whether knockdown of CK1ε could phenocopy TGR-1202 in the combination of idelalisib and carfilzomib, which was shown to be significantly less synergistic than TC (Figures 2A and 4A). CK1ε-targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA) reduced the protein level of CK1ε by >80%, but had no effect on c-myc, in the DLBCL cell line LY7 (Figure 7E; supplemental Figure 5B). In LY7 cells with wild-type CK1ε, the combination of idelalisib and carfilzomib produced only mild inhibition of phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, as evidenced by a partial downward mobility shift of 4E-BP1. In contrast, in the cells with CK1ε knockdown, the combination of idelalisib and carfilzomib effectively inhibited phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, demonstrated by a complete mobility shift of 4E-BP1 and a substantial decrease in phosphorylated 4E-BP1 at T70. These results indicate that targeting CK1ε complements PI3Kδ inhibition in the setting of combination therapy with carfilzomib.

TGR-1202 is active in treating DLBCL

In a phase 1 clinical trial of TGR-1202 as a single agent (#NCT01767766), partial response was observed in 3 of 14 patients with DLBCL (Figure 7F-G; supplemental Figure 6A-B). In contrast, earlier studies of idelalisib did not observe any responses in 9 patients with DLBCL.34 Furthermore, TGR-1202 was associated with very limited (2%) grade 3/4 diarrhea, compared with 13% seen with idelalisib in patients with similar clinical parameters.35 These results suggest that dual targeting of PI3Kδ and CK1ε by TGR-1202 may explain in part the preliminary activity of TGR-1202 in treating DLBCL and its distinctly favorable adverse event profile.

Discussion

For many years, c-Myc has been recognized as an “undruggable” target. More recently, BRD4 inhibitors have shown promise as a c-Myc–targeting therapy,36 with a few of them having entered phase 1 clinical studies. However, their safety and efficacy remain to be proven. In the current work, we aimed to explore new therapeutic strategies for targeting c-Myc that could be rapidly validated in clinical studies. To that end, we have demonstrated that the combination of TGR-1202 and carfilzomib, inhibitors of PI3Kδ and proteasome, respectively, potently disrupts the 4E-BP1–eIF4F–c-Myc axis, leading to antitumor effects of TGR-1202 and carfilzomib in cell lines and primary cells representing broad subtypes of B- and T-cell lymphoma, leukemia, and MM. The unique synergism of TGR-1202 and carfilzomib is driven in part by the unique pharmacologic activities of TGR-1202 reported in the current study.

Similar to the US Food and Drug Administration-approved drug idelalisib,26 TGR-1202 selectively inhibits PI3Kδ. Interestingly, our results indicate that TGR-1202 is more effective than idelalisib in disrupting the 4E-BP1–eIF4F–c-Myc axis and inducing cell death in lymphoma cells, both as a single agent and in combination with proteasome inhibitors. In agreement with these preclinical data, TGR-1202 has demonstrated clinical activity in DLBCL, whereas other PI3Kδ inhibitors failed.35 TGR-1202 possesses the unique capability to inhibit CK1ε (Figure 6), which distinguishes it from idelalisib. Collectively, these results support the hypothesis that cotargeting multiple regulators of 4E-BP1, including the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and CK1ε (as discussed in the following paragraphs), is required for optimal suppression of translation initiation.

Previous studies in breast cancer cell lines and mouse xenografts have demonstrated that CK1ε plays an important role in promoting cancer cell proliferation by regulating phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and initiation of mRNA translation.18 However, no CK1ε inhibitor is currently available for clinical study. The selective CK1ε inhibitor PF4800567 was very potent in the cell-free kinase assay, with an EC50 of 7.4 nM (Figure 6E). Surprisingly, very high concentrations of PF4800567, in the range of 25 to 50 μM, were required to inhibit phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 (Figure 7). The reason for such discrepancy is not understood. Interestingly, autophosphorylation of CK1ε at its C terminus inhibits the kinase activity of CK1ε.33 Conversely, it is possible that by potently inhibiting autophosphorylation, PF4800567 may somehow self-limit the inhibition of CK1ε.

In silico docking studies demonstrate that TGR-1202 binds the ATP pocket of CK1ε very well (Figure 6C-D). However, we do not yet have insights into how TGR-1202 interacts with CK1ε outside of the ATP pocket, which may be relevant to the relatively low potency of TGR-1202 with an EC50 of 6.0 μM in the cell-free kinase assay. Nevertheless, the drug TGR-1202 effectively inhibited autophosphorylation of CK1ε and phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 at 15 μM in lymphoma cells (Figures 6 and 7). We speculate that the 2 structural modules of TGR-1202, 1 for targeting PI3Kδ and 1 for CK1ε, may be actually advantageous for blocking the kinase domain of CK1ε. When administered at 1200 mg once daily in the phase 1 clinical study (#NCT01767766), TGR-1202 is very well tolerated and produced a maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) of 7700 ng/mL and steady-state concentration of 5200 ng/mL,37 corresponding to 13.5 and 9.1 μM. These results suggest that TGR-1202 is a first-in-class dual PI3Kδ/CK1ε inhibitor that may be adequate for targeting CK1ε in patients, especially in combination with carfilzomib.

Our results have a few clinical ramifications. The structural insights gained from TGR-1202 and CUX-03173 using in silico docking and from future crystallography studies may allow for further optimization of TGR-1202 and development of next-generation CK1ε inhibitors for cancer treatment. The combination of TGR-1202 and carfilzomib may represent a promising treatment of select patients with lymphoma that is characterized by c-Myc overexpression due to deregulated translation of c-Myc. A phase 1/2 study (NCT02867618) evaluating this regimen has been approved by the institutional review board and is open to accrual. As TGR-1202 is not associated with frequent colitis and pneumonitis,38 which have been reported for idelalisib,35 TGR-1202 will likely be well tolerated in combination with carfilzomib. Correlative studies of CK1ε, mTOR, 4E-BP1, and c-Myc in tumor samples before and after treatment are expected to provide insights into prognostic and predictive biomarkers for the treatment. Finally, if the combination of TGR-1202 and carfilzomib or TGR-1202 as a single agent is able to effectively turn off c-Myc, potentially, these treatments can be administered briefly and immediately before standard chemotherapy regimens as a strategy to enhance the cure potential and response rates of chemotherapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Amengual and Ahmed Sawas for critical reviewing, and Marc Brown for assistance with the computed tomography scan images. The authors thank TG Therapeutics for supplying TGR-1202.

Some experiments in this publication were performed at the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology Flow Cytometry Core, supported in part by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health under awards S10RR027050 and S10OD020056. Additional funding was provided by the Lymphoma Research Fund (C.D. and O.A.O.), TG Therapeutics (C.D.), the Columbia University Medical Center Precision Medicine Pilot Award (C.D.), and the Clinical Trial Office Pilot Award (C.D.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: C.D., M.R.L., L.S., X.O.J.S., M.A.M., S. Li, J.V., Y.H., X.X., and R.B.R. designed and performed the experiments and interpreted the results; S.-X.D., N.P.T., C.K., S. Lentzsch, D.A.F., B.H., D.W.L., and O.A.O. designed the experiments and provided advice; C.D. wrote the manuscript; and D.A.F., D.W.L., and O.A.O. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.D. has received research funding from TG Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for M.R.L. is Division of Medical Sciences, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Correspondence: Changchun Deng, Center for Lymphoid Malignancies, Columbia University Medical Center, 51 West 51st St, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10019; e-mail: cd2448@columbia.edu.