In this issue of Blood, Hunter et al describe how different genotypes cause different phenotypes and clinical features in Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM).1

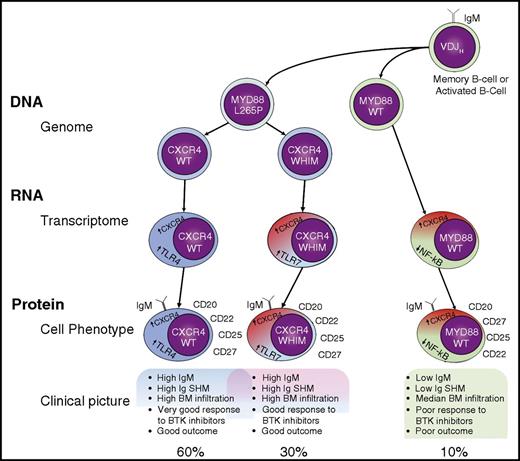

Genomic subclassification of WM. It is not clear whether a memory B cell or an activated B cell is the initiating tumor cell in WM, but we do know that it is a post–germinal center cell that has acquired a VDJH rearrangement and that expresses surface immunoglobulin M (IgM). This cell usually acquires an MYD88 L265P mutation and may subsequently acquire a CXCR4 WHIM mutation. This is the source of 3 possible genotypes: MYD88WT, MYD88L265PCXCR4WT, and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM. Although CXCR4 is overexpressed in all cases, the 3 genotypes correspond to 3 different transcriptome profiles (TLR7 overexpression profile, TLR4 overexpression profile, and NF-κB underexpression profile, among others). These 3 genomic and transcriptomic profiles are associated with similar phenotypic cellular and clinical profiles, although they do exhibit important differences, especially from the clinical point of view. SHM, somatic hypermutation; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; WT, wild-type.

Genomic subclassification of WM. It is not clear whether a memory B cell or an activated B cell is the initiating tumor cell in WM, but we do know that it is a post–germinal center cell that has acquired a VDJH rearrangement and that expresses surface immunoglobulin M (IgM). This cell usually acquires an MYD88 L265P mutation and may subsequently acquire a CXCR4 WHIM mutation. This is the source of 3 possible genotypes: MYD88WT, MYD88L265PCXCR4WT, and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM. Although CXCR4 is overexpressed in all cases, the 3 genotypes correspond to 3 different transcriptome profiles (TLR7 overexpression profile, TLR4 overexpression profile, and NF-κB underexpression profile, among others). These 3 genomic and transcriptomic profiles are associated with similar phenotypic cellular and clinical profiles, although they do exhibit important differences, especially from the clinical point of view. SHM, somatic hypermutation; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; WT, wild-type.

For a long time, WM has been diagnosed without the benefit of using specific genetic abnormalities to make the diagnosis. As is the case with other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) with many abnormalities within a disease category, the association was not strong enough to support a specific diagnosis. Thus, although WM is typically associated with del(6q21) or del(13q14), their frequencies are well below 100%, at 40% and 10%, respectively (lack of sensitivity), and the abnormalities are also present in other B-cell LPDs (lack of specificity). This landscape was revolutionized <5 years ago, when the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute group published their results on whole-genome sequencing in 30 cases of WM.2 In that study, the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) L265P mutation was seen in 90% of cases, a finding that they and other groups were soon able to reproduce in larger series of patients.3,4 This result and the very low frequencies reported for the commonest B-cell LPDs have converted the MYD88 L265P mutation into a very useful tool for the diagnosis of WM. The second most frequently mutated gene in WM is CXCR4, which occurs at a frequency of ∼30% of cases, two-thirds of which are C1013G, and is almost exclusively present in MYD88-mutated WM.4,5 Mutations of this gene, which are known to play a key role in cell adhesion to bone marrow (BM) stroma, are thought to cause WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) disease. In WM, somatic mutations of CXCR4 are associated with activating and prosurvival signaling of tumor cells, as well as the possible acquisition of resistance to several drugs, including Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors.5,6

These observations, together with several clinical findings, portray a WM landscape in which various genomic subgroups exist: MYD88WT, MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM, and MYD88L265PCXCR4WT (see figure).3,4 The most important factor supporting this initial genomic subclassification of WM is the differential response to BTK.7 However, the biologic reasons for the genetic translation into different clinical and treatment response subgroups are still unclear because the intermediate steps between the genomic abnormalities and the final phenotypes have yet to be identified.

In this issue, Hunter et al report their results of next-generation transcriptional profiling (“RNAseq”) in 57 patients with WM, and compare their results to those from B cells from normal controls. Accordingly, global transcription profiles and those associated with mutated MYD88, CXCR4, ARID1A abnormal cytogenetics, including 6q−, and familial WM are described and compared with those from normal B cells and the genomic WM counterpart. Some results are related to the B-cell origin of WM cells, such as the upregulation of VDJ recombination-related genes and the lack of expression of the class-switch recombination gene AICDA, which may explain why WM cells cannot undergo immunoglobulin class switching. The lack of similarity between WM and normal memory B cells raises the possibility of a different cell of origin of the WM cell than previously thought.8 However, it could also reflect the heterogeneity that is increasingly being discovered in the memory B-cell compartment.9 Furthermore, the expression of genes related to B-cell differentiation suggests that MYD88WTCXCR4WT can be derived from a cell in early stages of B-cell differentiation, which implies that MYD88 unmutated cases should be considered as having a disorder that is distinct from conventional WM. Interestingly, CXCR4 was overexpressed in all cases, irrespective of the CXCR4 mutation, which may explain why no substantive differences have been observed between the outcomes of mutated and WT CXCR4 cases.

The study also discovered separate transcriptional profiles for MYD88WTCXCR4WT, MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM, and MYD88L265PCXCR4WT cases, which highlights the pivotal role for MYD88 and CXCR4 signaling in WM. First, MYD88WT patients had much more heterogeneous RNA expression and differential RNA expression in >1000 genes than in MYD88L265P cases. These differences included the downregulation of the NF-κB pathway, which could account for changes in treatment sensitivity.5 Once again, this distinction is evidence that the MYD88WT WM could be considered as a distinct entity. Second, CXCR4WHIM mutations were responsible not only for the normalization of TLR4 signaling, driven by the presence of the MYD88L265P mutation, but also for the alternative activation of the TLR7 pathway. Likewise, CXCR4WHIM cases were associated with the normalization of many tumor suppressors that are overexpressed in response to the MYD88L265P mutation. Together, these differences help explain the diversity of WM described in previous studies. However, the article goes even further than this in revealing the existence of additional transcriptome variations associated with other genetic abnormalities, such as ARID1A mutations, 6q deletions, and familial genetic predisposition. This discovery reinforces the idea that WM is a heterogeneous disorder, just as (it is becoming increasingly clear) are all neoplastic disorders.

In summary, WM can be divided into 3 genetic subgroups (MYD88WT, MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM, and MYD88L265PCXCR4WT) in which the genetic lesions initiate a cascade of downstream consequences that explain the final 3 clinical phenotypes, and probably justify different therapeutic approaches. The latter will require well-designed clinical trials accompanied by basic and translational research projects (likely requiring international cooperation to ensure sufficient patients and resources) to provide a definitive answer. The path toward personalized therapy is coming to WM.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.