To the editor:

In the 5 May 2016 issue of Blood, Silvestre-Roig et al1 explored the phenotypic heterogeneity and the versatility of neutrophils, a heterogeneity established in part by an adaptable neutrophil lifespan. As noted by the authors, the classical understanding of the neutrophil population is one that is relatively homogenous, partially owing to what is generally believed to be their short lives in the blood. This latter observation is supported by a variety of analyses where neutrophil half-lives were measured on the order of hours.2 However, a more recent report on an in vivo labeling technique using heavy water (2H2O) has cast doubt on this classical view of neutrophil lifespan.3 There, the authors reported an average circulatory lifespan of 5.4 days, which elicited additional commentary in subsequent issues of Blood2,4,5 and elsewhere.6

We favor the term “half-removal time” over half-life because detecting that a neutrophil has left the free circulation is not the same as determining that it has died, because neutrophils are capable of chemotaxis, margination in some organs, and migration into tissues. Consequently, we do not discount the possibility of a long neutrophil lifespan with a short residence time in circulation. The time neutrophils remain in circulation has been studied for >70 years by a variety of labeling techniques.3,4,7-11 An overview of the history of neutrophil tracer labeling was very recently published12 in response to a new deuterium-labeled glucose and water tracing study,4 whose results seem to confirm the classical view of the short durations for neutrophils in the blood. Prior to the results reported using heavy water,3 where much longer lifespans were found, the reported range of half-removal times has been from 6.6 ± 1.1 hours using diisopropyl fluorophosphate32 labeling11 to 10.4 ± 1.5 hours using 3H–diisopropyl fluorophosphate,8 without considering the 16 hours reported after studies using irradiated cats.10 It should be noted, however, that labeling studies are not without limitations. In their response to letters about their article,3 Pillay et al5 pointed out that the reported short half-removal times may have been affected by neutrophils activated by ex vivo priming techniques.13 Further, results may be impacted by other factors including, and not limited to, the rate with which the label is picked up in the cells, the reuse/recycling of label within the cellular pool, and the loss of label.14 For these reasons, we sought an alternative method to provide bounds on the neutrophil half-removal and residence times.

Using fairly straightforward mathematical analyses of previously published data of the circulating neutrophil response to exogenous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), the principle cytokine responsible for the modulation of the neutrophil lineage,15 we present here a novel method for calculating the half-removal time of neutrophils from the blood without relying on any labeling experiments. Our results give a lower bound for the rate of removal of neutrophils from circulation, which in turn provides an upper bound on the half-removal time t1/2, the latter of which confirms the earlier, classical measurements of a short neutrophil lifespan.

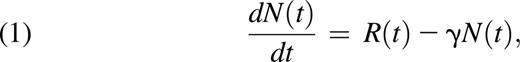

Neutrophils entering the circulation do so from the mature neutrophil reservoir in the bone marrow.15 Let R(t) be the rate neutrophils migrate out of the reservoir into the circulation. We assume R(t) is a non-negative quantity, implying that neutrophils released into the blood do not return to the bone marrow as functional cells (which does not discount their return to the bone marrow for the purpose of clearance from the body15 ). Using measurements for N(t) (the number of circulating neutrophils as a function of time), we can calculate dN(t)/dt, the rate of change of neutrophil numbers. Let γ > 0 be the rate of removal of neutrophils from the blood; then, at homeostasis

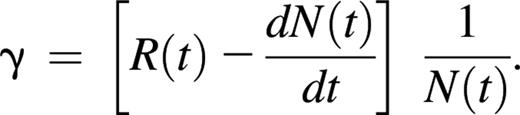

where the change in neutrophil counts in the blood with respect to time is equal to the rate with which neutrophils enter the circulation minus the rate with which they are removed from the circulation. In homeostatic conditions, dN(t)/dt = 0, and the input and removal from circulation are equal. If the input to circulation R(t) was known, it could be used to compute γ, but estimates are usually obtained from Equation 1 by first estimating the removal rate from circulation16 to obtain

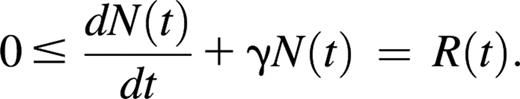

Here we will not estimate the unknown quantity R(t), but will simply exploit its positivity. From Equation 1 we obtain

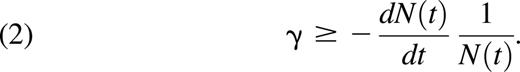

Rearranging this inequality gives a lower bound for γ as

The time-dependent lower bound for the constant γ found in Inequality 2 is only positive (and useful) when dN(t)/dt < 0, that is, when there is more removal than input of neutrophils to circulation, and the tightest bounds will be achieved when dN(t)/dt ≪ 0.

Information on neutrophil numbers in nonhomeostatic conditions is available when exogenous G-CSF is administered. In particular, the response of healthy volunteers to recombinant human G-CSF is reported in Krzyzanski et al (Figure 2)17 and Wang et al (Figure 7).18 In each study, volunteers were administered recombinant human G-CSF by both intravenous (IV) infusion and subcutaneous injection. We include only the results for IV administration because these achieve higher peak G-CSF concentrations and a much more rapid subsequent return to homeostatic concentrations than subcutaneous administration (Krzyzanski et al [Figure 2]17 and Wang et al [Figure 6]18 ). For clinically relevant IV doses, this results in the immediate recruitment of neutrophils to the circulation followed by relatively fast return toward homeostatic neutrophil concentrations, as seen in Figure 1B, which allows us to obtain good estimates for γ. We obtain measurements from each figure for N(t) at each of the sampling points in Figure 1B. Using Matlab,19 we fit a spline through the data, as previously described,16 to define the function NdatIV(t). Differentiating, we obtain dNdatIV(t)/dt, which is the rate of change of neutrophil numbers as a function of time, from the digitized data. The 3 rates of change from each of the data sources are shown in Figure 1C.

Model schematic and data sources visualized. (A) Neutrophils exit the marrow reservoir at rate R(t) before disappearing from the blood at rate γ. (B) Splined data of neutrophil responses to exogenous G-CSF IV infusions from Krzyzanski et al17 (Figure 2) and Wang et al18 (Figure 7). (C) Rate of change in neutrophil numbers in the blood calculated from digitized splined data (from Krzyzanski et al17 [Figure 2] and Wang et al18 [Figure 7]), differentiated with respect to time. Note that by 1 day after administration, dN(t)/dt < 0 for each of the 3 sources. (D) Right side of the Inequality 2; the maximal value provides a lower bound for γ.

Model schematic and data sources visualized. (A) Neutrophils exit the marrow reservoir at rate R(t) before disappearing from the blood at rate γ. (B) Splined data of neutrophil responses to exogenous G-CSF IV infusions from Krzyzanski et al17 (Figure 2) and Wang et al18 (Figure 7). (C) Rate of change in neutrophil numbers in the blood calculated from digitized splined data (from Krzyzanski et al17 [Figure 2] and Wang et al18 [Figure 7]), differentiated with respect to time. Note that by 1 day after administration, dN(t)/dt < 0 for each of the 3 sources. (D) Right side of the Inequality 2; the maximal value provides a lower bound for γ.

Using NdatIV(t) and dNdatIV(t)/dt in Inequality 2, we then determined the largest lower bound for γ > 0 for t where dNdatIV(t)/dt < 0. As seen in Figure 1B and D, the largest bounds are obtained close to where N(t) is decreasing most rapidly. The results of this analysis are given in Figure 1D and Table 1. In all 3 cases, the lower bounds for possible γ values were >0.985 days−1. Using Inequality 2, the maximum possible half-removal times were calculated by t1/2 = ln2/γ, and results are given in Table 1. Our results indicate that the half-removal time for neutrophils in circulation is <15 hours, which is consistent with the classical measurement of 7 hours,6 but is much shorter than and in disagreement with the more recently reported value of 3.7 days.1,3 Further, this value also agrees with the recent results from the 2-compartment modeling analysis of Lahoz-Beneytez et al,4 who reported a neutrophil half-life of ∼13 hours when R, the ratio of blood neutrophils to mitotic cells in the bone marrow, was included as a free parameter in their fitting. When using somewhat larger previously reported values for R, they obtained a neutrophil half-life of around 19 hours, which is inconsistent with our bound. Together, this suggests that previously published values for this ratio R may be overestimated, a finding that warrants more investigation.

Upper bounds on the half-removal time

| Dose, μg . | Removal rate (γ), days−1 . | Half-removal time (t1/2), days . | Source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 350 | 1.2773 | 0.54267 | Krzyzanski et al (Figure 2)17 |

| 375 | 0.98577 | 0.70315 | Wang et al (Figure 7)18 |

| 750 | 1.0917 | 0.6349 | Wang et al (Figure 7)18 |

| Dose, μg . | Removal rate (γ), days−1 . | Half-removal time (t1/2), days . | Source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 350 | 1.2773 | 0.54267 | Krzyzanski et al (Figure 2)17 |

| 375 | 0.98577 | 0.70315 | Wang et al (Figure 7)18 |

| 750 | 1.0917 | 0.6349 | Wang et al (Figure 7)18 |

γ Values presented here are the lower bounds calculated from inequality 2 using the data presented in Figure 1. From these lower bounds, an upper bound on the half-removal time can be calculated using t1/2 = ln2/γ. The average lower bound on γ was 1.1183 days−1, giving an upper bound of 0.6198 days, or 14.876 hours, for the half-removal time t1/2.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: The authors thank David C. Dale for introducing them to the issue at hand and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. A.R.H. and M.C.M. are supported by Natural Science and Engineering Research Council, Canada, for funding through the Discovery Grant program. M.C. is funded by grant DP5OD019851 from the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health to her principal investigator.

Contribution: M.C. conceived and implemented the model, performed the analyses, and wrote the manuscript; A.R.H. conceived and implemented the model and wrote the manuscript; and M.C.M. conceived the model and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Morgan Craig, Program for Evolutionary Dynamics, Harvard University, 1 Brattle Sq, Room 640, Cambridge, MA 02138; e-mail: morganlainecraig@fas.harvard.edu.

![Figure 1. Model schematic and data sources visualized. (A) Neutrophils exit the marrow reservoir at rate R(t) before disappearing from the blood at rate γ. (B) Splined data of neutrophil responses to exogenous G-CSF IV infusions from Krzyzanski et al17 (Figure 2) and Wang et al18 (Figure 7). (C) Rate of change in neutrophil numbers in the blood calculated from digitized splined data (from Krzyzanski et al17 [Figure 2] and Wang et al18 [Figure 7]), differentiated with respect to time. Note that by 1 day after administration, dN(t)/dt < 0 for each of the 3 sources. (D) Right side of the Inequality 2; the maximal value provides a lower bound for γ.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/128/15/10.1182_blood-2016-07-730325/4/m_1989f1.jpeg?Expires=1769322233&Signature=NWwYTSIeilYoysEGWQ66HHTQRkrikhMHAHjMKxwfe4wCchRYWrMCiwouvxCL6N4E4nIpqD3-G2ciTVHYrZ8OyubozyEcD9W737~PZLTCgmv~reULaPzkw60SQqjtAVOuNjDYmcp32m2eHPX7wLuxk5BhT5KW-XN3d0kaw~tlWFGbkPRnlxljMP1O0BexYK27icN~quqVCwcjaQ5MJEHrCH1fIHxKXMHzd3UyAihiqgYwQnrs676xqmz4CMyCV-2g5frh0iCxNIiwa6z1Sg4nZuakwg-lSiz7FWpFtWTPY-rmSti91wR9y6RARUfwg8UWsxu3QPUOZJiFXOKCmS7DXw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)