Key Points

SNPs in BANK1, CD247, and HLA-DPA1 were associated with risk of sclerotic GVHD.

HLA-DPA1∼B1 haplotypes and amino acid substitutions in the HLA-DP P1 peptide-binding pocket were associated with risk of sclerotic GVHD.

Abstract

Sclerotic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a distinctive phenotype of chronic GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, characterized by fibrosis of skin or fascia. Sclerotic GVHD has clinical and histopathological similarities with systemic sclerosis, an autoimmune disease whose risk is influenced by genetic polymorphisms. We examined 13 candidate single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have a well-documented association with systemic sclerosis to determine whether these SNPs are also associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD. The study cohort included 847 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with chronic GVHD. Genotyping was performed using microarrays, followed by imputation of unobserved SNPs. The donor rs10516487 (BANK1: B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1) TT genotype was associated with lower risk of sclerotic GVHD (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.21-0.87; P = .02). Donor and recipient rs2056626 (CD247: T-cell receptor ζ subunit) GG or GT genotypes were associated with higher risk of sclerotic GVHD (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.13-2.18; P = .007 and HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.19-2.32; P = .003, respectively). Donor and recipient rs987870 (5′-flanking region of HLA-DPA1) CC genotypes were associated with higher risk of sclerotic GVHD (HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.22-5.11; P = .01 and HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.00-4.54; P = .05, respectively). In further analyses, the recipient DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotype and certain amino acid substitutions in the recipient P1 peptide-binding pocket of the HLA-DP heterodimer were associated with risk of sclerotic GVHD. Genetic components associated with systemic sclerosis are also associated with sclerotic GVHD. HLA-DP–mediated antigen presentation, T-cell response, and B-cell activation have important roles in the pathogenic mechanisms of both diseases.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

This activity has been planned and implemented through the joint providership of Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology.

Medscape, LLC is accredited by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 1534.

Disclosures

Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, owns stock, stock options, or bonds from Pfizer. Associate Editor Robert Zeiser and the authors declare no competing financial interests.

Learning Objectives

Identify the clinical characteristics and incidence of sclerotic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), based on a literature review and findings in a study cohort.

Determine the associations of single-nucleotide polymorphisms with the risk of sclerotic GVHD, based on genotyping of a study cohort.

Determine the associations of polymorphic human leukocyte antigen haplotypes and amino acid substitutions with the risk for sclerotic GVHD.

Release date: September 15, 2016; Expiration date: September 15, 2017

Introduction

Sclerotic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) represents a distinctive phenotype of chronic GVHD, characterized by fibrosis of skin or fascia, and is often associated with severe disability and morbidity after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.1 The 3-year cumulative incidence of sclerosis is 20% after initial systemic treatment among patients with chronic GVHD, and the prevalence reaches 53% in patients with severe chronic GVHD.2,3 Pathogenic mechanisms of sclerotic GVHD remain elusive, but the cutaneous clinical manifestations resemble systemic sclerosis, a rare autoimmune disease whose risk is influenced by genetic polymorphisms. Both diseases are characterized by thickening of the skin due to accumulation of collagen and extensive fibrosis, but some manifestations differ. For example, systemic sclerosis often causes pulmonary hypertension, renal dysfunction, and cardiac dysfunction, whereas these manifestations rarely occur in patients with sclerotic GVHD.4,5 Therefore, pathogenic mechanisms of the two diseases are thought to differ, although they might share some similar mechanisms.4,6

To date, genetic risk factors for sclerotic GVHD have not been well defined, but candidate gene and genome-wide association studies have identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with systemic sclerosis.7 These SNPs include HLA and non-HLA variants involved in adaptive and innate immune responses. We hypothesized that the same SNPs might also have associations with the development of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD if the two diseases have similar pathogenic mechanisms. Therefore, we selected candidate SNPs that have a well-documented association with systemic sclerosis and examined their association with risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD. Identification of such associations would suggest similar pathogenic mechanisms between the two diseases, and might help to elucidate genetic mechanisms and treatment targets.

Methods

Literature search

A broad PubMed search was performed to identify SNPs published by June 2013, that met all of the following criteria using the terms “systemic sclerosis” and “polymorphism”: (1) SNPs associated with any form of systemic sclerosis, (2) SNPs identified in a large cohort including at least 1000 patients, (3) minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05, and (4) SNPs reported in at least 2 publications or reported with odds ratios (OR) ≥2.0, or ≤0.5 if the association was reported in only a single publication. SNPs from the same gene that shared strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with D prime >0.90 were combined, and a single “tag” SNP was chosen as representative of all SNPs in the LD group.

Study cohort

We identified 977 consecutive relapse-free patients who received systemic treatment of chronic GVHD after a first allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation between May 2000 and December 2009 at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC)/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.3 Among the 977 patients, 847 had recipient (n = 778) or donor (n = 808) samples available for genotyping, and 198 (23%) of the 847 patients developed sclerotic GVHD. Recipients and donors had given written consent allowing medical records and collected samples to be used for research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Institutional Review Board of the FHCRC approved the study.

Clinical assessments and definitions

Sample preparation, genotyping, and imputation

All recipient and donor samples were collected before transplantation according to approved research protocols. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood mononuclear cells or Esptein-Barr virus transformed B-lymphocyte cell lines using a Puregene kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genotyping assays used 3 different platforms: (1) the Affymetrix 5.0 Human GeneChip (206 recipients and 198 donors), (2) the Illumina 1M Quad (476 recipients and 458 donors), and (3) the Illumina 2.5M BeadArray (96 recipients and 152 donors). Amplification and hybridization for the Affymetrix 5.0 array was performed at the Affymetrix Service Laboratory (Santa Clara, CA), and amplification and hybridization for the Illumina BeadArrays was performed by the FHCRC Genomics Shared Resource laboratory. Data quality was assessed via 3 different methods: the Affymetrix Bayesian Robust Linear Model with Mahalanobis distance classifier-based “QC call rate,” the clustering call rate, and a polymerase chain reaction-based ABO and XY genotyping-based sample verification method.

The genotypes of the candidate SNPs were determined separately for each platform using the Affymetrix Bayesian Robust Linear Model with Mahalanobis distance classifier algorithm for the Affymetrix array (http://media.affymetrix.com/support/technical/whitepapers/brlmm_whitepaper.pdf) and the GeneCall algorithm for the Illumina array (http://illumina.com/documents/products/technotes/technote_gencall_data_analysis_software.pdf). Candidate SNPs not genotyped on the array were imputed using the 1000 Genomes Project phase 1 SNPs as a reference panel and the software IMPUTE version 2 (http://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/impute/impute_v2.html). The posterior probability of the most probable genotype is calculated as the probability of observing an unobserved genotype at the imputed locus, given all of the observed genotypes in the flanking region. The imputed SNP genotype was retained only if the average posterior probability exceeded 0.8. The imputed genotype was treated as missing if the average posterior probability was <0.8. The call rate reflects the percentage of nonmissing genotypes in each platform, and SNPs were treated as a quality control “failure” and excluded from analyses if the call rate in any typing platform was <0.90.

HLA-DPA1 and -DPB1 genotypes were determined by next-generation sequencing (MiSeq; Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) using commercial next-generation sequencing HLA reagents (Scisco Genetics Inc., Seattle, WA) in 165 recipients and 172 donors, and were imputed in 613 recipients and 636 donors with the use of SNP genotypes according to “Methods” described previously.8 The frequencies of HLA-DPA1 and -DPB1 alleles in the study cohort were comparable to those reported in a large population-based study.9

Statistical analysis

Sclerotic manifestations present at the onset of initial treatment of chronic GVHD were treated as an event at day 1 after treatment, and all patients were included in the analysis.3 In this cohort study, Cox regression models were used to examine allelic (additive) and genotypic (dominant and recessive) associations of donor and recipient SNPs with the risk of sclerotic GVHD.10 Results were analyzed without and with adjustments for clinical risk factors as defined in our previous study.3 These included stem cell graft source, HLA matching at A, B, C, DRB1, and DQB1 loci, donor-recipient ABO compatibility, and total body irradiation (TBI) exposure.3 Donor type (related vs unrelated) was not adjusted, because it was not associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD.3 Models adjusted for clinical risk factors were also adjusted for the first 4 principal components to control for population stratification. P values are two-sided, without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

Characteristics of the study cohort

The median age of the patients was 48 years (range, 1 to 78); 502 patients (59%) were males, 694 (82%) were white, and 745 (88%) received mobilized blood cell grafts. The median follow-up after onset of chronic GVHD among survivors was 81 months (range, 6 to 135). The cumulative incidence of sclerotic manifestations was 24% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21% to 27%) at 5 years after the initial systemic treatment of chronic GVHD. Other demographics of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Characteristics . | All patients . | Sclerosis . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present . | Absent . | ||

| (N = 847) . | (N = 198) . | (N = 649) . | |

| Patient age at transplantation, y | |||

| Median | 48 | 49 | 48 |

| Range | 1-78 | 2-69 | 1-78 |

| Donor-recipient gender combination, no. (%) | |||

| Male to male | 272 (32) | 66 (33) | 206 (32) |

| Male to female | 153 (18) | 33 (17) | 120 (18) |

| Female to male | 230 (27) | 42 (21) | 188 (29) |

| Female to female | 192 (23) | 57 (29) | 135 (21) |

| Patient race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 694 (82) | 171 (86) | 523 (81) |

| Others | 126 (15) | 19 (10) | 107 (16) |

| Unknown | 27 (3) | 8 (4) | 19 (3) |

| Diagnosis, no. (%) | |||

| Acute leukemia | 363 (43) | 86 (43) | 277 (43) |

| CML | 99 (12) | 19 (10) | 80 (12) |

| MDS or MPN | 201 (24) | 45 (23) | 156 (24) |

| CLL | 39 (5) | 9 (5) | 30 (5) |

| Malignant lymphoma or MM | 145 (17) | 39 (20) | 106 (16) |

| Disease risk at the time of transplantation,*no. (%) | |||

| Low risk | 316 (37) | 69 (35) | 247 (38) |

| High risk | 531 (63) | 129 (65) | 402 (62) |

| Stem cell graft source, no. (%) | |||

| Bone marrow | 102 (12) | 14 (7) | 88 (14) |

| Mobilized blood cells | 745 (88) | 184 (93) | 561 (86) |

| HLA and donor type,†no. (%) | |||

| HLA-matched related | 374 (44) | 91 (46) | 283 (44) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 326 (38) | 86 (43) | 240 (37) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 13 (2) | 1 (1) | 12 (2) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 134 (16) | 20 (10) | 114 (18) |

| ABO compatibility, no. (%) | |||

| Match | 472 (56) | 117 (59) | 355 (55) |

| Minor mismatch | 170 (20) | 48 (24) | 122 (19) |

| Major mismatch | 205 (24) | 33 (17) | 172 (27) |

| Intensity of conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |||

| High intensity | 601 (71) | 132 (67) | 469 (72) |

| Reduced intensity | 246 (29) | 66 (33) | 180 (28) |

| TBI dose in conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |||

| None | 348 (41) | 67 (34) | 281 (43) |

| ≤450 cGy | 297 (35) | 78 (39) | 219 (34) |

| >450 cGy | 202 (24) | 53 (27) | 149 (23) |

| Prior grade 2-4 acute GVHD, no. (%) | 619 (73) | 137 (69) | 482 (74) |

| Characteristics . | All patients . | Sclerosis . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present . | Absent . | ||

| (N = 847) . | (N = 198) . | (N = 649) . | |

| Patient age at transplantation, y | |||

| Median | 48 | 49 | 48 |

| Range | 1-78 | 2-69 | 1-78 |

| Donor-recipient gender combination, no. (%) | |||

| Male to male | 272 (32) | 66 (33) | 206 (32) |

| Male to female | 153 (18) | 33 (17) | 120 (18) |

| Female to male | 230 (27) | 42 (21) | 188 (29) |

| Female to female | 192 (23) | 57 (29) | 135 (21) |

| Patient race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 694 (82) | 171 (86) | 523 (81) |

| Others | 126 (15) | 19 (10) | 107 (16) |

| Unknown | 27 (3) | 8 (4) | 19 (3) |

| Diagnosis, no. (%) | |||

| Acute leukemia | 363 (43) | 86 (43) | 277 (43) |

| CML | 99 (12) | 19 (10) | 80 (12) |

| MDS or MPN | 201 (24) | 45 (23) | 156 (24) |

| CLL | 39 (5) | 9 (5) | 30 (5) |

| Malignant lymphoma or MM | 145 (17) | 39 (20) | 106 (16) |

| Disease risk at the time of transplantation,*no. (%) | |||

| Low risk | 316 (37) | 69 (35) | 247 (38) |

| High risk | 531 (63) | 129 (65) | 402 (62) |

| Stem cell graft source, no. (%) | |||

| Bone marrow | 102 (12) | 14 (7) | 88 (14) |

| Mobilized blood cells | 745 (88) | 184 (93) | 561 (86) |

| HLA and donor type,†no. (%) | |||

| HLA-matched related | 374 (44) | 91 (46) | 283 (44) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 326 (38) | 86 (43) | 240 (37) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 13 (2) | 1 (1) | 12 (2) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 134 (16) | 20 (10) | 114 (18) |

| ABO compatibility, no. (%) | |||

| Match | 472 (56) | 117 (59) | 355 (55) |

| Minor mismatch | 170 (20) | 48 (24) | 122 (19) |

| Major mismatch | 205 (24) | 33 (17) | 172 (27) |

| Intensity of conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |||

| High intensity | 601 (71) | 132 (67) | 469 (72) |

| Reduced intensity | 246 (29) | 66 (33) | 180 (28) |

| TBI dose in conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |||

| None | 348 (41) | 67 (34) | 281 (43) |

| ≤450 cGy | 297 (35) | 78 (39) | 219 (34) |

| >450 cGy | 202 (24) | 53 (27) | 149 (23) |

| Prior grade 2-4 acute GVHD, no. (%) | 619 (73) | 137 (69) | 482 (74) |

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm.

The low-risk category included CML in chronic phase, acute leukemia in first remission, MDS without excess blasts, and aplastic anemia. The high-risk category included all other diseases and stages.

Recipient HLA-matching with the donor, as determined by methods informative for 4-digit resolution of HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, and DQB1 alleles. In 14 pairs, matching was determined by methods informative for 2-digit resolution of one or more HLA-A, B, or C alleles.

Candidate genes and SNPs

A broad search of the PubMed database identified 15 SNPs in 13 genes that were associated with susceptibility to systemic sclerosis and met all of the required criteria described in “Methods”: B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1 (BANK1), BLK, CD247, HLA-DRA, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPA1, IL12RB2, IRF8, PTPN22, STAT4, TNFSF4, TNIP1, and TNPO3-IRF5. Thirteen of these 15 SNPs yielded genotyped or imputed data that passed quality control, and all had an MAF ≥0.05 (Table 2). The MAF for each SNP was consistent with the values reported in studies of systemic sclerosis.11-19 Two SNPs (rs11642873 and rs1234314) did not pass quality control because of low call rates on one of the genotyping platforms (see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). Supplemental Table 2 shows the genotype distributions and MAFs for each SNP, according to the presence or absence of sclerosis.

Candidate SNPs

| Gene . | SNP . | Chromosome . | Alleles* . | MAF† . | Reported OR (95% CI) for systemic sclerosis‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BANK1 | rs3733197 | 4 | A/G | 0.36 | 0.73 (0.61-0.87) |

| BANK1 | rs10516487 | 4 | T/C | 0.30 | 0.77 (0.64-0.93) |

| BLK | rs2736340 | 8 | T/C | 0.29 | 1.18 (1.00-1.40) |

| CD247 | rs2056626 | 1 | G/T | 0.41 | 0.82 (0.76-0.88) |

| HLA-DRA | rs3129882 | 6 | G/A | 0.42 | 2.17 (1.88-2.50) |

| HLA-DQB1 | rs9275390 | 6 | C/T | 0.27 | 2.38 (2.13-2.67) |

| HLA-DPA1 | rs987870 | 6 | C/T | 0.15 | 2.09 (1.78-2.45) |

| IL12RB2 | rs3790567 | 1 | A/G | 0.28 | 1.17 (1.11-1.24) |

| PTPN22 | rs2476601 | 1 | T/C | 0.08 | 1.38 (1.10-1.80) |

| STAT4 | rs7574865 | 2 | T/G | 0.24 | 1.54 (1.36-1.74) |

| TNFSF4 | rs2205960 | 1 | T/G | 0.22 | 1.37 (1.12-1.66) |

| TNIP1 | rs2233287 | 5 | A/G | 0.08 | 1.31 (1.15-1.43) |

| TNPO3-IRF5 | rs10488631 | 7 | C/T | 0.13 | 1.50 (1.35-1.67) |

| Gene . | SNP . | Chromosome . | Alleles* . | MAF† . | Reported OR (95% CI) for systemic sclerosis‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BANK1 | rs3733197 | 4 | A/G | 0.36 | 0.73 (0.61-0.87) |

| BANK1 | rs10516487 | 4 | T/C | 0.30 | 0.77 (0.64-0.93) |

| BLK | rs2736340 | 8 | T/C | 0.29 | 1.18 (1.00-1.40) |

| CD247 | rs2056626 | 1 | G/T | 0.41 | 0.82 (0.76-0.88) |

| HLA-DRA | rs3129882 | 6 | G/A | 0.42 | 2.17 (1.88-2.50) |

| HLA-DQB1 | rs9275390 | 6 | C/T | 0.27 | 2.38 (2.13-2.67) |

| HLA-DPA1 | rs987870 | 6 | C/T | 0.15 | 2.09 (1.78-2.45) |

| IL12RB2 | rs3790567 | 1 | A/G | 0.28 | 1.17 (1.11-1.24) |

| PTPN22 | rs2476601 | 1 | T/C | 0.08 | 1.38 (1.10-1.80) |

| STAT4 | rs7574865 | 2 | T/G | 0.24 | 1.54 (1.36-1.74) |

| TNFSF4 | rs2205960 | 1 | T/G | 0.22 | 1.37 (1.12-1.66) |

| TNIP1 | rs2233287 | 5 | A/G | 0.08 | 1.31 (1.15-1.43) |

| TNPO3-IRF5 | rs10488631 | 7 | C/T | 0.13 | 1.50 (1.35-1.67) |

The first allele is designated as the minor allele and the second allele is designated as the major allele.

Data represent results from the combined cohort of recipients and donors who had genotyping in this study. MAFs were similar between donors and recipients, and are consistent with results from studies of patients with systemic sclerosis.11-19

All ORs were derived from allelic genetic models.

Candidate SNPs associated with risk of sclerotic GVHD

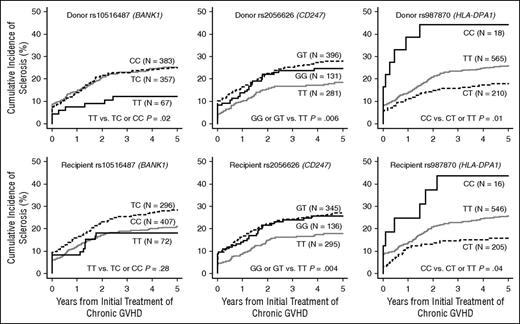

Three SNPs showed statistically significant associations with risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD (Table 3). SNP rs10516487 (BANK1) in donors was associated with a decreased risk of sclerotic GVHD in the recessive model (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.87; P = .02). SNP rs2056626 (CD247: T-cell receptor [TCR] ζ subunit) in both donors and recipients was associated with an increased risk of sclerotic GVHD in the allelic model (adjusted HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.00-1.51; P = .04 and adjusted HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.01-1.52; P = .04, respectively), and in the dominant model (adjusted HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.13-2.18; P = .007 and adjusted HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.19-2.32; P = .003, respectively). SNP rs987870 (HL A-DPA1) in both donors and recipients was associated with an increased risk of sclerosis in the recessive model (adjusted HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.22-5.11; P = .01 and adjusted HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.00-4.54; P = .05, respectively). We evaluated the joint association of donor and recipient genotypes with the risk of sclerotic GVHD among patients with both donor and recipient genotyping. The results for rs2056626 (CD247) and rs987870 (HLA-DPA1) were inconclusive as to whether the donor and recipient associations are independent. Cumulative incidence frequencies of sclerotic GVHD according to genotypes of these 3 SNPs are shown in Figure 1. Results for other candidates are shown in supplemental Table 3. Overall, adjustment had only minor effects on the association results. Polymorphisms in HLA-DRA and HLA-DQB1 were not statistically associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD, although power to observe a statistically significant association is ≥80% based on the OR reported for systemic sclerosis shown in Table 2.

Risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD, according to SNPs in donors and recipients

| Genome . | Gene . | SNP . | Alleles* . | N . | Model . | Groups compared . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||||||

| Donor | BANK1 | rs10516487 | T/C | 807 | Allelic | TT vs TC vs CC | 0.83 (0.66-1.04) | .11 | 0.84 (0.67-1.05) | .12 |

| Dominant | TT or TC vs CC | 0.91 (0.68-1.20) | .50 | 0.92 (0.69-1.22) | .55 | |||||

| Recessive | TT vs TC or CC | 0.43 (0.21-0.88) | .02 | 0.43 (0.21-0.87) | .02 | |||||

| Donor | CD247 | rs2056626 | G/T | 808 | Allelic | GG vs GT vs TT | 1.23 (1.01-1.51) | .04 | 1.23 (1.00-1.51) | .04 |

| Dominant | GG or GT vs TT | 1.58 (1.14-2.18) | .006 | 1.57 (1.13-2.18) | .007 | |||||

| Recessive | GG vs GT or TT | 1.05 (0.72-1.53) | .82 | 1.04 (0.71-1.53) | .84 | |||||

| Recipient | CD247 | rs2056626 | G/T | 776 | Allelic | GG vs GT vs TT | 1.27 (1.04-1.55) | .02 | 1.24 (1.01-1.52) | .04 |

| Dominant | GG or GT vs TT | 1.62 (1.17-2.24) | .004 | 1.66 (1.19-2.32) | .003 | |||||

| Recessive | GG vs GT or TT | 1.13 (0.78-1.64) | .53 | 1.04 (0.71-1.52) | .85 | |||||

| Donor | HLA-DPA1 | rs987870 | C/T | 793 | Allelic | CC vs CT vs TT | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | .45 | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | .44 |

| Dominant | CC or CT vs TT | 0.77 (0.55-1.07) | .12 | 0.76 (0.54-1.06) | .11 | |||||

| Recessive | CC vs CT or TT | 2.44 (1.20-4.96) | .01 | 2.50 (1.22-5.11) | .01 | |||||

| Recipient | HLA-DPA1 | rs987870 | C/T | 767 | Allelic | CC vs CT vs TT | 0.81 (0.59-1.12) | .20 | 0.84 (0.61-1.15) | .28 |

| Dominant | CC or CT vs TT | 0.69 (0.49-0.99) | .04 | 0.72 (0.50-1.03) | .07 | |||||

| Recessive | CC vs CT or TT | 2.17 (1.02-4.63) | .04 | 2.13 (1.00-4.54) | .05 | |||||

| Genome . | Gene . | SNP . | Alleles* . | N . | Model . | Groups compared . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||||||

| Donor | BANK1 | rs10516487 | T/C | 807 | Allelic | TT vs TC vs CC | 0.83 (0.66-1.04) | .11 | 0.84 (0.67-1.05) | .12 |

| Dominant | TT or TC vs CC | 0.91 (0.68-1.20) | .50 | 0.92 (0.69-1.22) | .55 | |||||

| Recessive | TT vs TC or CC | 0.43 (0.21-0.88) | .02 | 0.43 (0.21-0.87) | .02 | |||||

| Donor | CD247 | rs2056626 | G/T | 808 | Allelic | GG vs GT vs TT | 1.23 (1.01-1.51) | .04 | 1.23 (1.00-1.51) | .04 |

| Dominant | GG or GT vs TT | 1.58 (1.14-2.18) | .006 | 1.57 (1.13-2.18) | .007 | |||||

| Recessive | GG vs GT or TT | 1.05 (0.72-1.53) | .82 | 1.04 (0.71-1.53) | .84 | |||||

| Recipient | CD247 | rs2056626 | G/T | 776 | Allelic | GG vs GT vs TT | 1.27 (1.04-1.55) | .02 | 1.24 (1.01-1.52) | .04 |

| Dominant | GG or GT vs TT | 1.62 (1.17-2.24) | .004 | 1.66 (1.19-2.32) | .003 | |||||

| Recessive | GG vs GT or TT | 1.13 (0.78-1.64) | .53 | 1.04 (0.71-1.52) | .85 | |||||

| Donor | HLA-DPA1 | rs987870 | C/T | 793 | Allelic | CC vs CT vs TT | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | .45 | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | .44 |

| Dominant | CC or CT vs TT | 0.77 (0.55-1.07) | .12 | 0.76 (0.54-1.06) | .11 | |||||

| Recessive | CC vs CT or TT | 2.44 (1.20-4.96) | .01 | 2.50 (1.22-5.11) | .01 | |||||

| Recipient | HLA-DPA1 | rs987870 | C/T | 767 | Allelic | CC vs CT vs TT | 0.81 (0.59-1.12) | .20 | 0.84 (0.61-1.15) | .28 |

| Dominant | CC or CT vs TT | 0.69 (0.49-0.99) | .04 | 0.72 (0.50-1.03) | .07 | |||||

| Recessive | CC vs CT or TT | 2.17 (1.02-4.63) | .04 | 2.13 (1.00-4.54) | .05 | |||||

The first allele is designated as the minor allele and the second allele is designated as the major allele.

Adjusted for stem cell graft source, HLA matching, ABO compatibility, TBI dose, and principal components.

Cumulative incidence frequencies of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD, according to rs10516487 (BANK1), rs2056626 (CD247), and rs987870 (HLA-DPA1) genotypes in the donors and recipients. Black solid lines represent groups with the homozygous minor allele, gray solid lines represent groups with the homozygous major allele, and dotted black lines represent heterozygotes.

Cumulative incidence frequencies of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD, according to rs10516487 (BANK1), rs2056626 (CD247), and rs987870 (HLA-DPA1) genotypes in the donors and recipients. Black solid lines represent groups with the homozygous minor allele, gray solid lines represent groups with the homozygous major allele, and dotted black lines represent heterozygotes.

Analysis of HLA-DPB1 mismatching

Results for rs987870 (HLA-DPA1) motivated further exploration of the association between HLA-DPB1 mismatching and the risk of sclerotic GVHD. Among 619 HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, and DQB1-matched patient and donor pairs, recipient mismatching at HLA-DPB1 was present in 243 (39%) pairs but was not statistically associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.76-1.45; P = .77). Likewise, nonpermissive recipient T-cell epitope mismatching at HLA-DPB120 was present in 56 (9%) pairs but was not statistically associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.30-1.14; P = .11). The recently reported SNP rs92777534 linked to HLA-DP expression21 was also not statistically associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD (data not shown).

Analysis of HLA-DPA1∼B1 haplotype and HLA-DP P1 peptide-binding pocket

The risk of sclerotic GVHD was increased when donors or recipients were homozygous for the rs987870 minor C allele but was paradoxically decreased when donors or recipients were heterozygous, as compared with donors or recipients homozygous for the major T allele (Figure 1). We used 2 approaches to unravel this paradox. Because this SNP is located in the 5′-flanking region of HLA-DPA1, we tested whether any of the most frequent HLA-DPA1∼DPB1 haplotypes were associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD (Table 4).22 Among 4 common HLA-DPA1∼B1 haplotypes with frequencies ≥5%, DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 in the recipient was associated with an increased risk of sclerotic GVHD (adjusted HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.10-2.15; P = .01) (Table 4; Figure 2A).

Risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD, according to HLA-DPA1∼DPB1 haplotypes in donors and recipients

| Genome . | Haplotype* . | Frequency . | No. with haplotype/total (%) . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | ||||

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 | 0.40 | 492/808 (63) | 1.24 (0.92-1.68) | .16 | 1.23 (0.90-1.67) | .19 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 | 0.40 | 501/778 (62) | 1.53 (1.10-2.12) | .01 | 1.54 (1.10-2.15) | .01 |

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*02:01 | 0.14 | 191/808 (25) | 0.79 (0.56-1.11) | .17 | 0.84 (0.60-1.18) | .32 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*02:01 | 0.13 | 207/778 (26) | 0.93 (0.66-1.31) | .67 | 0.97 (0.69-1.38) | .88 |

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:02 | 0.11 | 160/808 (21) | 0.90 (0.63-1.28) | .56 | 0.87 (0.61-1.25) | .45 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:02 | 0.11 | 168/778 (21) | 0.80 (0.55-1.18) | .27 | 0.77 (0.53-1.13) | .19 |

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*03:01 | 0.08 | 118/808 (15) | 0.99 (0.68-1.47) | .95 | 0.96 (0.64-1.42) | .82 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*03:01 | 0.08 | 128/778 (16) | 1.02 (0.68-1.54) | .93 | 0.91 (0.60-1.37) | .64 |

| Genome . | Haplotype* . | Frequency . | No. with haplotype/total (%) . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | ||||

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 | 0.40 | 492/808 (63) | 1.24 (0.92-1.68) | .16 | 1.23 (0.90-1.67) | .19 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 | 0.40 | 501/778 (62) | 1.53 (1.10-2.12) | .01 | 1.54 (1.10-2.15) | .01 |

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*02:01 | 0.14 | 191/808 (25) | 0.79 (0.56-1.11) | .17 | 0.84 (0.60-1.18) | .32 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*02:01 | 0.13 | 207/778 (26) | 0.93 (0.66-1.31) | .67 | 0.97 (0.69-1.38) | .88 |

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:02 | 0.11 | 160/808 (21) | 0.90 (0.63-1.28) | .56 | 0.87 (0.61-1.25) | .45 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:02 | 0.11 | 168/778 (21) | 0.80 (0.55-1.18) | .27 | 0.77 (0.53-1.13) | .19 |

| Donor | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*03:01 | 0.08 | 118/808 (15) | 0.99 (0.68-1.47) | .95 | 0.96 (0.64-1.42) | .82 |

| Recipient | DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*03:01 | 0.08 | 128/778 (16) | 1.02 (0.68-1.54) | .93 | 0.91 (0.60-1.37) | .64 |

Haplotypes with frequencies ≥0.05 are examined. HLA-DPA1∼DPB1 haplotypes were estimated as described previously.22

Adjusted for stem cell graft source, HLA matching, ABO compatibility, TBI dose, and principal components.

Cumulative incidence frequencies of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD. Results are shown (A) according to the presence or absence of the HLA-DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotype in the recipient, and (B) according to presence or absence of HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 alleles encoding heterodimers with a Q∼GPM P1 pocket. Solid lines represent groups with the haplotype or P1 pocket, and dotted lines represent groups without the haplotype or P1 pocket.

Cumulative incidence frequencies of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD. Results are shown (A) according to the presence or absence of the HLA-DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotype in the recipient, and (B) according to presence or absence of HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 alleles encoding heterodimers with a Q∼GPM P1 pocket. Solid lines represent groups with the haplotype or P1 pocket, and dotted lines represent groups without the haplotype or P1 pocket.

HLA-DP molecules have peptide-presentation P1 peptide-binding pockets characterized by M (methionine) or Q (glutamine) at position 31 of the DPα chain and by glutamic acid-alanine-valine (EAV) or glycine-proline-methionine (GPM) motifs at positions 85 to 87 of the DPβ chain (Figure 3).9 As a second approach in unraveling the paradox, we evaluated associations of each P1 pocket motif with the risk of sclerotic GVHD (Table 5). Previous studies have shown significant negative LD between HLA-DPA1 alleles encoding Q and HLA-DPB1 alleles encoding GPM. Haplotype frequencies for these Q and GPM encoding alleles occur much less frequently than expected from their respective individual frequencies.9 Nonetheless, staining with two different HLA-DP–specific antibodies demonstrated surface expression of HLA-DP on B cells from individuals with alleles encoding only Q-bearing DPα chains and GPM-bearing DPβ chains, indicating no intrinsic physical constraint on their ability to form stable heterodimers (supplemental Figure 1). Therefore, we defined P1 pocket motifs by considering DPα∼DPβ heterodimers encoded in trans, together with those encoded in cis. The risk of sclerotic GVHD was decreased in recipients who had HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 alleles encoding Q∼GPM P1 pockets compared with those who did not (adjusted HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42-0.92; P = .02) (Table 5; Figure 2B).

Crystal structure of an HLA-DP2 heterodimer in complex with a self-peptide. The HLA-DPα chain is shown in yellow, and the HLA-DPβ chain is shown in blue. Shown in red is the P1 pocket formed in part by residue 31 of the α chain and residues 85 to 87 of the β chain. The self-peptide filling the gap between the α helices of the heterodimer is shown in green. HLA-DP2 is a heterodimer encoded by DPA1*0103 and DPB1*0201 with M at position 31 of the α chain and GPM at positions 85 to 87 of the β chain. The hydrophobic aromatic side chain of phenylalanine at the P1 anchor position of the peptide projects into the hydrophobic M∼GPM P1 pocket. Substitution of Q for M at position 31 in the α chain would replace a hydrophobic residue with a more hydrophilic residue. This substitution would not alter the overall structure of the heterodimer but would change the P1 anchor residues that fit the pocket and the repertoire of peptides that can be presented. The crystal structure of an HLA-DPB1 heterodimer with a Q∼GPM P1 pocket has not been determined. The structure shown in the figure was rendered with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.7.4.4, Schrödinger, LLC.).

Crystal structure of an HLA-DP2 heterodimer in complex with a self-peptide. The HLA-DPα chain is shown in yellow, and the HLA-DPβ chain is shown in blue. Shown in red is the P1 pocket formed in part by residue 31 of the α chain and residues 85 to 87 of the β chain. The self-peptide filling the gap between the α helices of the heterodimer is shown in green. HLA-DP2 is a heterodimer encoded by DPA1*0103 and DPB1*0201 with M at position 31 of the α chain and GPM at positions 85 to 87 of the β chain. The hydrophobic aromatic side chain of phenylalanine at the P1 anchor position of the peptide projects into the hydrophobic M∼GPM P1 pocket. Substitution of Q for M at position 31 in the α chain would replace a hydrophobic residue with a more hydrophilic residue. This substitution would not alter the overall structure of the heterodimer but would change the P1 anchor residues that fit the pocket and the repertoire of peptides that can be presented. The crystal structure of an HLA-DPB1 heterodimer with a Q∼GPM P1 pocket has not been determined. The structure shown in the figure was rendered with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.7.4.4, Schrödinger, LLC.).

Risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD, according to HLA-DPB1 P1 pocket motifs in donors and recipients

| Genome . | Motif* . | Frequency, no./total (%) . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| Donor | M∼GPM | 707/808 (88%) | 0.94 (0.61-1.44) | .78 | 0.94 (0.60-1.46) | .77 |

| M∼EAV | 383/808 (47%) | 0.85 (0.64-1.13) | .26 | 0.81 (0.61-1.09) | .16 | |

| Q∼GPM | 220/808 (27%) | 0.71 (0.50-1.00) | .05 | 0.75 (0.53-1.07) | .11 | |

| Q∼EAV | 289/808 (36%) | 0.78 (0.58-1.07) | .12 | 0.81 (0.59-1.11) | .20 | |

| Recipient | M∼GPM | 674/778 (87%) | 1.02 (0.66-1.58) | .94 | 1.01 (0.64-1.60) | .95 |

| M∼EAV | 373/778 (48%) | 0.90 (0.67-1.20) | .47 | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | .29 | |

| Q∼GPM | 208/778 (27%) | 0.57 (0.39-0.84) | .004 | 0.62 (0.42-0.92) | .02 | |

| Q∼EAV | 281/778 (36%) | 0.74 (0.54-1.02) | .07 | 0.80 (0.57-1.11) | .18 | |

| Genome . | Motif* . | Frequency, no./total (%) . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| Donor | M∼GPM | 707/808 (88%) | 0.94 (0.61-1.44) | .78 | 0.94 (0.60-1.46) | .77 |

| M∼EAV | 383/808 (47%) | 0.85 (0.64-1.13) | .26 | 0.81 (0.61-1.09) | .16 | |

| Q∼GPM | 220/808 (27%) | 0.71 (0.50-1.00) | .05 | 0.75 (0.53-1.07) | .11 | |

| Q∼EAV | 289/808 (36%) | 0.78 (0.58-1.07) | .12 | 0.81 (0.59-1.11) | .20 | |

| Recipient | M∼GPM | 674/778 (87%) | 1.02 (0.66-1.58) | .94 | 1.01 (0.64-1.60) | .95 |

| M∼EAV | 373/778 (48%) | 0.90 (0.67-1.20) | .47 | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | .29 | |

| Q∼GPM | 208/778 (27%) | 0.57 (0.39-0.84) | .004 | 0.62 (0.42-0.92) | .02 | |

| Q∼EAV | 281/778 (36%) | 0.74 (0.54-1.02) | .07 | 0.80 (0.57-1.11) | .18 | |

Defined by M (methionine) or Q (glutamine) at position 31 of the HLA-DPα chain and by EAV or GPM motifs at positions 85 to 87 of the HLA-DPβ chain. Presence of the motif was defined by considering HLA-DPα/DPβ heterodimers encoded both in cis and in trans.

Adjusted for stem cell graft source, HLA matching, ABO compatibility, TBI dose, and principal components.

With adjustments for the presence of DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotypes and Q∼GPM P1 pockets, differences in the risk of sclerotic GVHD between rs987870 heterozygotes and TT homozygotes were not statistically significant (supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Within the entire cohort, rs987870 genotypes, DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotypes, and Q∼GPM P1 pockets showed independent associations with the risk of sclerotic GVHD (Table 6).

Risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD, according to recipient HLA-DP variations

| Recipient variation . | HR* (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-DPA1 rs987870 CC vs CT or TT genotypes | 2.66 (1.18-5.97) | .02 |

| DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotype | 1.59 (1.11-2.27) | .01 |

| Q∼GPM P1 pocket† | 0.64 (0.43-0.96) | .03 |

| Recipient variation . | HR* (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-DPA1 rs987870 CC vs CT or TT genotypes | 2.66 (1.18-5.97) | .02 |

| DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotype | 1.59 (1.11-2.27) | .01 |

| Q∼GPM P1 pocket† | 0.64 (0.43-0.96) | .03 |

Adjusted for stem cell graft source, HLA matching, ABO compatibility, TBI dose, and principal components.

Heterodimers with Q (glutamine) at position 31 of the HLA-DPα chain and GPM at positions 85 to 87 of the HLA-DPβ chain.

Discussion

We examined 13 candidate SNPs that had a well-documented association with susceptibility to systemic sclerosis, under the hypothesis that the same SNPs may also have associations with development of sclerotic GVHD if the two diseases share similar pathogenic mechanisms. The candidate SNPs all map to genes or regions involved in immune function. We found that donor rs10516487 (BANK1), and donor and recipient rs2056626 (CD247), and rs987870 (5′-flanking region of HLA-DPA1) were associated with the risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD. Despite adequate power to detect associations, candidate SNPs in HLA-DRA and HLA-DQB1 did not show statistically significant associations with risk of sclerotic GVHD. These results highlight similarities and differences in the mechanisms that cause sclerotic GVHD as compared with systemic sclerosis, and suggest a critical role of the adaptive immune system including B-cell activation, T-cell antigen receptor response, and HLA-DP–mediated antigen presentation in the pathogenic mechanisms of both sclerotic GVHD and systemic sclerosis.

BANK1 is expressed exclusively in B cells and encodes a signaling molecule with stimulatory and inhibitory functions. BANK1 is a Lyn tyrosine kinase substrate that promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors implicated in B-cell activation.23 On the other hand, BANK1 modulates hyperactive B-cell responses by inhibiting AKT activation in CD40-mediated pathways.24 SNP rs10516487 (BANK1) is 1 of 3 functional SNPs affecting BANK1 regulatory sites.25,26 As compared with the rs10516487 C major allele, the T minor allele decreases BANK1 expression, reduces the activity of BANK1 variants with increased potential for self-association, and thereby reduces B-cell responses.27 In several large studies, the same minor allele has been associated with decreased susceptibility to systemic sclerosis,11,28 systemic lupus erythematosus,25 and rheumatoid arthritis.26 These results suggest that sclerotic GVHD shares a BANK1-mediated pathogenic mechanism with several autoimmune diseases. These results also suggest that sclerotic GVHD might be ameliorated or prevented by inhibition of BANK1 function or related components of B-cell activation. In fact, rituximab has efficacy for treatment of sclerotic GVHD,29 and patients with higher percentages of activated B cells had better clinical responses to rituximab.30 A recent study showed that antibodies from donor B cells perpetuate cutaneous sclerotic GVHD in mice.31

Functional activation of T cells depends on surface expression of TCR-CD3 complexes. CD247 encodes the TCR ζ (CD3ζ) subunit and plays a crucial role in coupling antigen recognition to several intracellular signal-transduction pathways.32 CD3ζ is a key element in the signaling function of chimeric antigen receptors in cancer immunotherapy.33 Altered expression of CD247 may cause T-cell dysfunction, and failure of tolerance in chronic autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.34,35 The G minor allele of SNP rs2056626 (CD247) has shown allelic associations with reduced susceptibility to systemic sclerosis in 4 independent studies.13,14,19,36 In addition, minor alleles of two other CD247 SNPs in LD with rs2056626 were associated with reduced susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.37-39 Although causal effects of these SNPs on CD247 expression and function have not been completely characterized, variation in this gene correlated with altered T-cell activation and autoimmune diabetes in mice.40 In our study, the rs2056626 G minor allele in both recipients and donors showed allelic and dominant associations with increased risk of sclerosis in patients with chronic GVHD. These results suggest that variable expression of CD3ζ might play a pathogenic role in sclerotic GVHD and other autoimmune diseases by altering TCR signaling. We note that the rs2056626 (CD247) minor allele was associated with an increased risk of sclerotic chronic GVHD but with a decreased susceptibility to systemic sclerosis. We can only speculate that the downstream effect of variable signaling through the TCR may differ in the context of an allo-immune response as compared with the autoimmune response involved in systemic sclerosis.

HLA-DP variants have been associated with susceptibility to certain immune-mediated diseases.14,41 We found that SNP rs987870 (HLA-DPA1) was associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD. The same SNP has been associated with increased susceptibility to asthma, as well as systemic sclerosis.14,42 SNP rs987870 is located in the 5′ noncoding region of HLA-DPA1, a region characterized by strong LD and constrained haplotypic pairings between HLA-DPA1 and DPB1 alleles. Our results suggest that differences in the frequencies of DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotypes or HLA-DP molecules with Q∼GPM motifs account for the decreased risk of sclerosis among rs987870-heterozygous patients as compared with those who are homozygous for the major T allele. Previous studies have not evaluated associations of the DPA1*01:03∼DPB1*04:01 haplotype or the Q∼GPM motif with either systemic sclerosis or sclerotic GVHD. These 3 mutually independent associations require verification in other cohorts of patients with sclerotic GVHD and systemic sclerosis.

In previous studies, HLA-DPB1 mismatching between the donor and recipient was associated with an increased risk of acute GVHD.43 In the present study, neither HLA-DPB1 mismatching nor HLA-DPB1 nonpermissive mismatching was statistically associated with risk of sclerotic GVHD. The recently reported SNP rs92777534 linked to HLA-DP expression21 was also not statistically associated with the risk of sclerotic GVHD. Taken together, these results suggest that intrinsic HLA-DP functional mechanisms account for the association of HLA-DP variants with the risk of sclerotic GVHD.

This study has limitations. Power to examine some of the weaker SNP associations reported for systemic sclerosis was low, and our analysis did not adjust for multiple comparisons. We were unable to determine whether the donor and recipient CD247 and HLA-DPB1 genotypes contribute independently to the risk of sclerosis. No other cohort currently has sufficient numbers of patients with chronic GVHD, together with the annotated onset of sclerosis and the DNA samples needed for a replication study. Therefore, collaborative efforts will be needed so that future studies could verify whether positive results from this study hold true in other cohorts of patients with chronic GVHD.

Our findings suggest that genetic variation can modify the immune pathology and significantly alter the disease phenotype of chronic GVHD. Our results also support the hypothesis that HLA-DP–mediated presentation of specific peptides may have pathogenic or protective effects related to sclerotic GVHD. Further efforts to identify such peptides and genetic variations associated with specific phenotypes of chronic GVHD may expand our understanding of the responsible pathogenic mechanisms, thereby suggesting novel approaches for targeted therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NIH National Marrow Donor Program for providing cryopreserved blood samples, Jenna Gravley for technical assistance, Anajane Smith for HLA-typing, and Gary Schoch for data management.

This study was supported by grants from the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL105914 and HL87690) (J.A.H., P.J.M., E.H.W., M.J.B., B.E.S., D.M.L., W.F., and L.-P.Z.), National Cancer Institute (CA18029) (S.J.L. and M.E.D.F.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL093294) (M.J.B.), and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (15K19563) (Y.I.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.I., P.J.M., and J.A.H. designed the study, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the paper; D.M.L., W.F., L.-P.Z., and B.E.S. performed the statistical analysis; M.E.D.F., S.J.L., and P.A.C. collected data and wrote the report; E.H.W. and M.J.B. contributed to interpretation of the data and wrote the report; D.E.G. and N.L. performed experiments; and all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yoshihiro Inamoto, National Cancer Center Hospital, 5-1-1 Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan; e-mail: yinamoto@fredhutch.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal