Key Points

tfec controls the expression of cytokines in the vascular niche.

tfec expands HSCs in a non–cell-autonomous fashion.

Abstract

In mammals, embryonic hematopoiesis occurs in successive waves, culminating with the emergence of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the aorta. HSCs first migrate to the fetal liver (FL), where they expand, before they seed the bone marrow niche, where they will sustain hematopoiesis throughout adulthood. In zebrafish, HSCs emerge from the dorsal aorta and colonize the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT). Recent studies showed that they interact with endothelial cells (ECs), where they expand, before they reach their ultimate niche, the kidney marrow. We identified tfec, a transcription factor from the mitf family, which is highly enriched in caudal endothelial cells (cECs) at the time of HSC colonization in the CHT. Gain-of-function assays indicate that tfec is capable of expanding HSC-derived hematopoiesis in a non–cell-autonomous fashion. Furthermore, tfec mutants (generated by CRISPR/Cas9) showed reduced hematopoiesis in the CHT, leading to anemia. Tfec mediates these changes by increasing the expression of several cytokines in cECs from the CHT niche. Among these, we found kitlgb, which could rescue the loss of HSCs observed in tfec mutants. We conclude that tfec plays an important role in the niche to expand hematopoietic progenitors through the modulation of several cytokines. The full comprehension of the mechanisms induced by tfec will represent an important milestone toward the expansion of HSCs for regenerative purposes.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are self-renewing multipotent progenitors that constitute the source of the hematopoietic tissue. Therefore, they represent a crucial population for regenerative medicine and have already been used in gene therapy protocols to correct immunodeficiencies.1-3 These protocols rely on the ex vivo expansion of autologous HSCs, using a cocktail of cytokines (interleukin 3, stem cell factor [SCF]/cKit-Ligand, FLT3L) that maintain and expand human HSCs, although inefficiently.1,4,5 Therefore, a better understanding of the niche where HSCs normally expand is required.

In mammals, HSCs are produced from the embryonic aorta.6,7 They then colonize the fetal liver (FL), where they undergo symmetrical divisions to expand their initial number7-11 before seeding the bone marrow. Many data point to the existence of several signals that can maintain adult HSCs in a quiescent state,12 making the FL the only niche where HSCs actively expand.

In the mouse FL, HSCs migrate closely to the developing vasculature13,14 and rely on many cytokines for their expansion. Stromal cell lines such as AFT024, which maintain HSC activity, express high levels of SCF/cKitL.15,16 By comparing these lines with cells that do not support HSC activity, further cytokines have been identified, such as insulin growth factors and angiopoietins.17 The FL CD3+ cells produce angiopoietin-like protein-2 and angiopoietin-like protein-3, which also specifically expand HSCs.18 Furthermore, chemical screens of small molecules allowed the identification of new compounds and pathways involved in HSC expansion. One example is StemRegenin-1, which expands human HSCs by acting on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway,19,20 and another is UM171, a pyrimidoindole derivative that stimulates HSC expansion through an unknown pathway.21 Finally, dmPGE2, revealed in a zebrafish chemical screen,22 also gives a competitive advantage to transplanted HSCs in primates and humans.23,24

During zebrafish development, HSCs also emerge from the dorsal aorta,25,26 then home to the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT), where they expand between 3 and 4 days postfertilization (dpf).14,27,28 When HSCs reach the CHT, they trigger a “cuddling” behavior from caudal endothelial cells (cECs). This interaction maintains contact between HSCs and stromal cells, inducing HSC proliferation.14 These stromal cells express cxcl12a14 and might have many origins, including the somitic tissue.29 Cxcl12 is well characterized for its role in HSC retention and survival in mice,30-32 but many more as-yet-uncharacterized signals could contribute to HSC expansion in the CHT.

To identify these signals, several genetic pathways have been identified, but none has been characterized within the vascular compartment. Ebf2 is necessary for the establishment of the osteoblastic niche in the bone marrow and controls the expression of several genes involved in the maintenance of HSCs.33 Foxc1 controls the expression of cxcl12 in stromal cells.31,34 During embryogenesis, mouse ATF4 controls cytokine expression from FL stromal cells to promote HSC expansion.35

Our study provides new insights on the role of tfec in the zebrafish HSC niche. Tfec is a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor that belongs to the mitf family. Although most members of this family are involved in neural crest differentiation into pigment cells,36,37 previous work showed that tfec was expressed in the posterior blood island (PBI) at 24 hours postfertilization (hpf)37 and was involved in myeloid biology.38 Recently, high-throughput screening identified that mouse Tfec could enhance HSC expansion, either in a cell-autonomous or non–cell-autonomous way.39,40 However, this screening method did not allow to describe the precise role of tfec during HSC development. Here, we uncovered the physiological role of tfec during embryogenesis. We found that cECs forming the CHT niche specifically express tfec. Moreover, by increasing tfec expression, we could modulate the expression of cytokines from cECs, leading to HSC expansion in the CHT, a phenotype that disappeared in tfec mutant zebrafish. We also show that tfec acts non–cell-autonomously by overexpressing this transcript only in the vascular niche. Finally, tfec mutants could be rescued by the overexpression of kitlgb. Thus, tfec modulates the vascular niche to control HSC expansion in the zebrafish CHT.

Experimental procedures

Zebrafish strains and husbandry

AB* zebrafish strains, along with transgenic strains and mutant strains, were kept in a 14/10 h light/dark cycle at 28°C. Embryos were obtained as described previously.41 We used the following transgenic animals: Tg(flk1:Cre)s898, Tg(βactin2:loxp-STOP-loxp-DsRed-express)sd525 (referred to as βactinSwitch:DsRed), Tg(flk1:Gal4)bw9,42 Tg (flk1:eGFP)s84,43 Tg(flk1:Hsa.HRAS-mCherry)s896,44 Tg(cmyb:GFP)zf169,,22 and cd41:GFP.45 Hereafter, transgenic lines will be referred to without Tg(xxx:xxx) nomenclature. The following mutants were used: mindbombta52b,46 clochem34,47,48 runx1w84x,49 and cmybt25127.50

Whole-mount in situ hybridization staining and analysis

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) was performed on 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed embryos. Digoxigenin-labeled probes were synthesized using a RNA Labeling kit (SP6/T7; Roche). RNA probes were generated by linearization of TOPO-TA or ZeroBlunt vectors (Invitrogen) containing the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified cDNA sequence. WISH was performed as previously described.51 All injections were repeated 3 separate times. Analysis was performed using the unpaired Student t test (GraphPad Prism). Embryos were imaged in 100% glycerol, using an Olympus MVX10 microscope. Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify and clone cDNA for the production of ISH probes are listed in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site.

Cell sorting and flow cytometry

Embryos were incubated in 0.5 mg/mL Liberase (Roche) solution for 90 min at 33°C, then dissociated and resuspended in 0.9× PBS-1% fetal calf serum. We excluded dead cells by SYTOX-red (Life Technologies) staining. Cell sorting was performed using an Aria II (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative real-time PCR and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

RNA was extracted using RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a Superscript III kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using KAPA SYBR FAST Universal qPCR Kit (KAPA BIOSYSTEMS) and run on a CFX connect real-time system (Bio Rad). All primers are listed in supplemental Table 2. Analysis was performed using an unpaired Student t test in Prism. Each qPCR experiment was performed using biological triplicates. For experiments using qPCR with or without injection, each n represents an average of biological triplicates from a single experiment. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times, and fold-change averages from each experiment were combined.

Synthesis of full-length mRNA

mRNA was reverse transcribed using mMessage mMachine kit SP6 (Ambion) from a linearized pCS2+ vector containing PCR-amplified product. After transcription, RNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction.

Confocal microscopy and immunofluorescence staining

Transgenic fluorescent embryos were embedded in 1% agarose in a glass-bottom dish.25 Immunofluorescence double staining was performed as described previously,52 with chicken anti-GFP (1:400; Life Technologies) and rabbit anti-phospho-histone 3 (pH3) antibodies (1:250; Abcam). AlexaFluor 488-conjugated anti-chicken secondary antibody (1:1000; Life Technologies) and AlexaFluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; Life Technologies) were used to reveal primary antibodies. Confocal imaging was performed using a Nikon inverted A1r spectral.

Generation of transgenic and mutant animals

For Tg(UAS:hl-ztfec) fish generation, a Tol2 vector containing 4xUAS promoter, the sequence for hl-ztfec (including STOP codon), and a poly-adenylation signal sequence was generated by subcloning. Zebrafish embryos were injected with 25 pg of the final Tol2 vector, along with 25 pg Tol2 transposase mRNA. Injected F0 adults were mated to flk1:Gal4 zebrafish, and F1 offspring were screened to assess germline integration of the Tol2 construct. After WISH, embryos were genotyped by PCR. Genotyping primers are in supplemental Table 3.

For CRISPR/Cas9-mediated generation of tfec mutants, single-guide RNA was generated by annealing oligonucleotides at 95°C for 5 min, and then 22°C for 45 min, before they were diluted 20-fold and ligated into the pDR274 plasmid (kind gift from Keith Joung; Addgene plasmid 42250),53 linearized with BsaI. Guide RNA was generated using the MEGAshortscript T7 kit (Ambion). Per embryo, 500 pg recombinant Cas9 protein (PNAbio) and 250 pg guide RNA were injected. Embryos were screened using primers that flanked the target region (supplemental Table 3). Heteroduplexes were formed by heating PCR product at 95°C for 2 minutes and then cooling from 95°C to 85°C at 2°C/s, then cooling to 25°C at 0.1°C/s. Ten microliters of DNA was digested with T7 endonuclease for 30 min at 37°C and then loaded on a 1% agarose gel. Mutant alleles were identified by sequencing.

Results

Tfec-P2 specifically marks the endothelial niche in the CHT

Previous work showed tfec expression in neural crest cells and the PBI.37 To investigate the relevance of tfec to hematopoiesis, we examined its expression pattern in wild-type (WT) and mutant embryos, and in fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS)-sorted cells. We confirmed, by WISH, that tfec is highly expressed along the neural crest and in the PBI as early as 20 hpf (Figure 1A) and at 24 hpf (Figure 1B). Overall, tfec was expressed in the PBI between 16 and 36 hpf and weakens after 38 hpf (supplemental Figure 1A-D).37 At 20 to 24 hpf, tfec expression overlaps with flk1, suggesting expression within cECs (Figure 1C-D). The expression of tfec was further investigated by qPCR (using primers that recognize all tfec transcripts) in ECs sorted from flk1:eGFP embryos. On average, there was a 35-fold enrichment of tfec in ECs compared with eGFP-negative sorted cells from the whole embryo (Figure 1I). Next, we examined the expression of tfec in mindbomb mutants, which lack HSCs,54 by examining both runx1 and tfec. Runx1 signal allowed us to discriminate mib−/− from their wild-type siblings. In mib−/− embryos, tfec expression was normal in the PBI, implicating its expression to be independent of HSCs (Figure 1E-F). However, tfec expression was lost in the neural crest, suggesting a role for NOTCH in the control of tfec expression in these cells. Finally, we analyzed the expression of tfec in cloche mutants that are devoid of vasculature and blood.47 In cloche−/− embryos, tfec was not expressed in the PBI (Figure 1G-H), correlating with its expression in cECs.

tfec is highly enriched in caudal endothelial cells. (A-B) Representative embryos after in situ hybridization (ISH) of tfec on WT embryos at 20 and 24 hpf. (C-D) ISH of tfec (black) and flk1 (red) on WT embryos at 20 and 24 hpf. (E-F) ISH of tfec (black: PBI and neural crest) and runx1 (black: aorta) at 24 hpf on either mindbomb−/− (loss of runx1 staining) or siblings with WT phenotype (normal runx1 staining). (G-H) ISH of tfec (black) and gata1 (red) on either cloche−/− (loss of gata1 staining) or WT sibling (normal gata1 staining). Prime panels depict the region indicated by the dashed outline box. The numbers in the bottom right corner (here and in following figures, unless otherwise stated) of the image indicate the number of embryos with the represented phenotype out of the total number of embryos. (I) qPCR data examining tfec expression (using primers that recognize all transcripts) in FACS-sorted cells from flk1:eGPF embryos. eGFP-negative cells from the whole embryo, eGFP-positive cells from the whole embryos, eGFP-positive cells from dissected heads and trunks (heads), or eGFP-positive cells from dissected tails (tails) were sorted from 26-hpf embryos. Statistical analysis was completed using an un-paired Student t test. Data represents mean ± SEM ****P < .001.

tfec is highly enriched in caudal endothelial cells. (A-B) Representative embryos after in situ hybridization (ISH) of tfec on WT embryos at 20 and 24 hpf. (C-D) ISH of tfec (black) and flk1 (red) on WT embryos at 20 and 24 hpf. (E-F) ISH of tfec (black: PBI and neural crest) and runx1 (black: aorta) at 24 hpf on either mindbomb−/− (loss of runx1 staining) or siblings with WT phenotype (normal runx1 staining). (G-H) ISH of tfec (black) and gata1 (red) on either cloche−/− (loss of gata1 staining) or WT sibling (normal gata1 staining). Prime panels depict the region indicated by the dashed outline box. The numbers in the bottom right corner (here and in following figures, unless otherwise stated) of the image indicate the number of embryos with the represented phenotype out of the total number of embryos. (I) qPCR data examining tfec expression (using primers that recognize all transcripts) in FACS-sorted cells from flk1:eGPF embryos. eGFP-negative cells from the whole embryo, eGFP-positive cells from the whole embryos, eGFP-positive cells from dissected heads and trunks (heads), or eGFP-positive cells from dissected tails (tails) were sorted from 26-hpf embryos. Statistical analysis was completed using an un-paired Student t test. Data represents mean ± SEM ****P < .001.

Distinct promoters control the tissue-specific expression of the different human TFEC isoforms.55 In zebrafish, 3 distinct promoters have been described: tfec-P1 (NM_001030105.2), tfec-P2 (XM_005164535.2), and tfec-P3 (XM_009299965.1) (supplemental Figure 2A). Each isoform encodes a protein with a unique first exon, a glutamine-rich domain, a MAPK domain, a transactivator domain, a basic helix–loop–helix domain, and a cyclic adenosine monophosphate phosphorylation site, a structure very similar to that of its paralogues and orthologs (supplemental Figure 2B). To understand the expression pattern of each transcript of ztfec in the PBI, we cloned the unique 5′ untranslated region and first exon of each tfec isoform to create unique probes. Compared with our original tfec probe that recognizes all variants (common tfec: supplemental Figure 2C), tfec-P1 was restricted to neural crests at 24 hpf (supplemental Figure 2D), and tfec-P2 was restricted to the PBI at 24 hpf (supplemental Figure 2E). We could not obtain any detectable signal for tfec-P3 by in situ hybridization, although it was detected in cECs by qPCR (data not shown). We confirmed these results by qPCR. In FACS-sorted cECs (from flk1:eGFP embryos at 26 hpf), tfec-P2 was highly enriched in cECs when compared with the whole embryo, whereas tfec-P1 showed no enrichment, in agreement with its specific expression in neural crest cells (supplemental Figure 2F).

In summary, the tfec-P2 variant is specifically expressed in cECs, independent of HSCs, suggesting a non–cell-autonomous role in hematopoiesis. Next, we investigated the function of tfec in the CHT.

tfec gain-of-function results in HSC expansion and enhanced hematopoiesis

Overexpressing the full-length mRNA tfec-P2 and tfec-P1 led to high lethality rates at 6 to 8 hpf when injected at any concentrations (data not shown). We therefore decided to clone a mRNA, using an in-frame ATG codon in exon 2 that was previously described.37 The resulting mRNA encodes a protein lacking the glutamine-rich domain, which mimics the human TFEC protein56 (supplemental Figure 2B). We called this isoform human-like zebrafish tfec (hl-ztfec) (supplemental Figure 2B), as the human ortholog lacks the glutamine-rich domain.

Both cmyb and ikaros were augmented after hl-ztfec injection, suggesting an expansion of HSCs in the CHT, as well as in the thymus and kidney glomerulus (Figure 2A-B). To rule out any contribution of tfec to HSC specification or emergence, we analyzed runx1 at 26 hpf, rag1 at 96 hpf, and flk1 at 24 hpf and found no changes in these markers (supplemental Figure 3A-F). When we performed these experiments in runx1 and cmyb mutants, which both lack functional HSCs (supplemental Figure 3G-N), we did not observe this expansion of hematopoietic markers at 4 dpf, suggesting tfec specifically affects HSC expansion in the CHT, and not any other hematopoietic progenitors.

tfec overexpression augments the number and proliferation (G2/M phase) of HSPCs in the CHT. (A-B) ISH against cmyb and ikaros (markers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [HSPCs]), prime panels depict the region indicated by the dashed outline box which highlights thymus staining. (C) Schematic indicating approximate imaging area in the tail, as indicated by the black box. (D) Confocal imaging in the CHT of double positive flk1:mCherry/cmyb :GPF embryos in NI or following hl-ztfec (+tfec) injection at 3 and 4 dpf. (F) Confocal imaging in the CHT of triple-positive flk1:eGPF/flk1:Cre/βactinSwitch:DsRed embryos in NI or after hl-ztfec (+tfec) injection at 3 and 4 dpf. (E,G) Analysis of embedded HSPCs at 3 dpf and HSPCs closely associated to endothelial cells at 4 dpf. (H) Imaging schematic at 3 or 4 dpf. (I-N) anti-GFP and pH3 immunostaining at 3 or 4 dpf of either noninjected (NI) or hl-ztfec-injected (+tfec) cmyb:eGPF embryos. (O) Quantification of the number of the pH3+ HSPCs in NI or hl-ztfec-injected embryos at 3 or 4 dpf. Scale bars represent 25 μm; error bars represent SEM. Statistical analysis was completed using an unpaired Student t test, comparing NI with hl-ztfec (+tfec)-injected embryos. NS, no significance. *P < .05; **P < .01. White arrows indicate embedded HSPCs at 3 dpf or closely associated HSPCs at 4 dpf in D and F and represent proliferating HSPCs in I-N.

tfec overexpression augments the number and proliferation (G2/M phase) of HSPCs in the CHT. (A-B) ISH against cmyb and ikaros (markers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [HSPCs]), prime panels depict the region indicated by the dashed outline box which highlights thymus staining. (C) Schematic indicating approximate imaging area in the tail, as indicated by the black box. (D) Confocal imaging in the CHT of double positive flk1:mCherry/cmyb :GPF embryos in NI or following hl-ztfec (+tfec) injection at 3 and 4 dpf. (F) Confocal imaging in the CHT of triple-positive flk1:eGPF/flk1:Cre/βactinSwitch:DsRed embryos in NI or after hl-ztfec (+tfec) injection at 3 and 4 dpf. (E,G) Analysis of embedded HSPCs at 3 dpf and HSPCs closely associated to endothelial cells at 4 dpf. (H) Imaging schematic at 3 or 4 dpf. (I-N) anti-GFP and pH3 immunostaining at 3 or 4 dpf of either noninjected (NI) or hl-ztfec-injected (+tfec) cmyb:eGPF embryos. (O) Quantification of the number of the pH3+ HSPCs in NI or hl-ztfec-injected embryos at 3 or 4 dpf. Scale bars represent 25 μm; error bars represent SEM. Statistical analysis was completed using an unpaired Student t test, comparing NI with hl-ztfec (+tfec)-injected embryos. NS, no significance. *P < .05; **P < .01. White arrows indicate embedded HSPCs at 3 dpf or closely associated HSPCs at 4 dpf in D and F and represent proliferating HSPCs in I-N.

Previously, cECs have been shown to be important for creating a niche by embedding HSCs and orienting cell division.14 We investigated whether the number of endothelial-embedded HSCs augmented after hl-ztfec injection by using double-transgenic flk1:mCherry; cmyb:GFP embryos and counting the number of GFP-positive cells (HSCs) embedded within their mCherry-positive endothelial niche at 3 and 4 dpf (supplemental Figure 4A-C). In control embryos, we could score similar numbers, as previously described at 72 hpf.14 At 4 dpf, this number decreased, as previously reported,14 and cmyb-positive HSCs were less closely associated with vasculature (supplemental Figure 4C). When hl-ztfec was overexpressed, we observed an increased number of HSCs present in the niche at 3 dpf (Figure 2D-E). This increase was maintained at 4 dpf when hl-ztfec was overexpressed (Figure 2D-E), despite a decrease in HSPCs in control embryos from 3 to 4 dpf.14 These results were confirmed by using flk1:mCherry;cd41:eGFP embryos, where small cd41low cells represent HSCs (supplemental Figure 4H-I). The number of hematopoietic progenitors was significantly increased at 3 dpf, but not at 4 dpf, after hl-ztfec overexpression (supplemental Figure 4H-I). We confirmed these findings by using triple transgenic flk1:eGFP;flk1:Cre;β-actin:Switch-DsRed embryos that express DsRed in HSCs and their progeny,25 while coexpressing GFP and DsRed in ECs. We identified embedded HSCs at 3 dpf and HSPCs closely associated to cECs at 4 dpf (supplemental Figure 4D-F). As before, after hl-ztfec mRNA injection, the number of HSPCs present in the niche at 3 and 4 dpf was increased (Figure 2F-G).

As tfec increased the number of HSCs present within the vascular niche, we examined whether there was an increase in proliferating HSCs. We took noninjected and hl-ztfec-injected cmyb:GFP embryos and stained for both GFP and phospho-Histone 3 (pH3) to quantify proliferating HSCs, as previously described52 (Figure 2H-O). At 3 dpf, hl-ztfec mRNA injection significantly increased the number of proliferating HSCs (cmyb:GFP+/pH3+) within the CHT, but only led to a small and nonsignificant increase at 4 dpf (Figure 3H, L-O), which was confirmed using cd41:eGFP transgenic embryos and counting the number of proliferating HSCs (cd41:eGFP+/pH3+) within the CHT (supplemental Figure 4J-Q). Thus, overexpression of tfec results in HSC expansion, as well as enhanced caudal hematopoiesis.

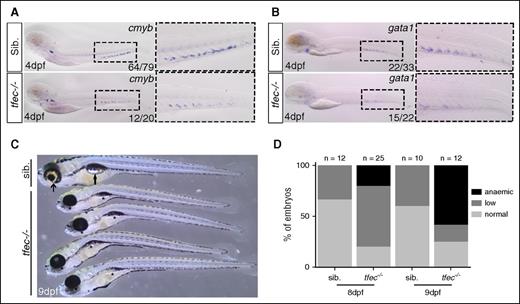

tfec−/−mutants have reduced hematopoiesis and become anemic. (A-B) ISH for cmyb and gata1 at 4 dpf in WT/tfec+/− embryos or tfec−/− mutant embryos. Sib. represents WT/tfec+/− genotype. (C) Brightfield image at 9 dpf showing tfec−/− mutants and their siblings. Arrows indicate normal pigmented eye in siblings and inflated swim bladder; asterisks indicate loss of eye pigmentation and uninflated swim bladder in mutants. (D) Circulating blood phenotype at 8 and 9 dpf characterized by normal blood flow (normal), low circulating number of cells (low), and almost complete loss of circulating cells (anemia).

tfec−/−mutants have reduced hematopoiesis and become anemic. (A-B) ISH for cmyb and gata1 at 4 dpf in WT/tfec+/− embryos or tfec−/− mutant embryos. Sib. represents WT/tfec+/− genotype. (C) Brightfield image at 9 dpf showing tfec−/− mutants and their siblings. Arrows indicate normal pigmented eye in siblings and inflated swim bladder; asterisks indicate loss of eye pigmentation and uninflated swim bladder in mutants. (D) Circulating blood phenotype at 8 and 9 dpf characterized by normal blood flow (normal), low circulating number of cells (low), and almost complete loss of circulating cells (anemia).

tfec mutant embryos do not maintain HSCs and develop anemia

We examined HSC expansion in a novel tfec mutant fish, generated by CRISPR/Cas9 technology. We selected a mutant with a 32-bp deletion that resulted in a premature STOP codon and a severely truncated protein (supplemental Figure 5A-C). At 4 dpf, we found a reduction of cmyb (HSCs), gata1 (erythroid lineage), mpx (neutrophils), and mfap4 (macrophages) in tfec−/− mutants compared with their control siblings (Figure 3A-B; supplemental Figure 5D-E), but no change in runx1 or rag1 expression at 26 and 96 hpf, respectively (supplemental Figure 5F-I). In addition, tfec−/− adults are nonviable and die around 10-11 dpf. Larvae were characterized by a loss of eye pigmentation, retarded growth, a noninflated swim bladder, and anemia (Figure 3C). We first detected a reduction in circulating blood cells at 8 dpf in tfec−/− embryos (Figure 3D; supplemental Videos 1-2). We also observed this decrease in circulating cells in tfec−/−; gata1:DsRed embryos (supplemental Video 3). At 9 dpf, the majority of tfec−/− embryos were anemic (Figure 3D). Finally, we could rescue the loss of HSCs (cmyb signal) in the CHT by overexpressing tfec mRNA in the tfec−/− mutant embryos (supplemental Figure 5J-K). Altogether, this set of data indicates that tfec plays a crucial role in HSC expansion and maintenance.

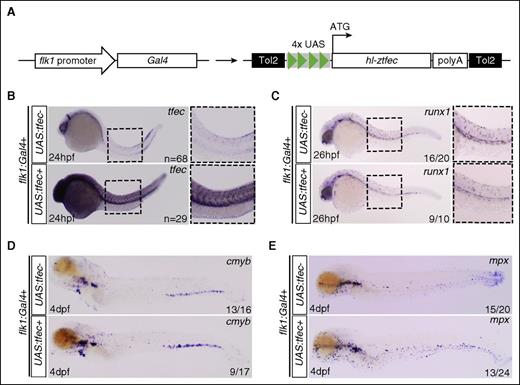

tfec expands HSCs non–cell-autonomously

Others have shown that TFEC can improve HSC reconstitution non–cell-autonomously.39,40 Our own results suggest a similar mechanism, as tfec is primarily expressed in cECs, and tfec mutants exhibit a normal HSC specification at 24 to 26 hpf. To confirm our hypothesis, we generated flk1:Gal4;UAS:hl-ztfec double-transgenic embryos to overexpress hl-ztfec specifically in ECs (Figure 4A). First, we confirmed that our system worked efficiently by examining the expression of tfec in transgenic embryos. Flk1:Gal4 single-positive embryos showed normal expression of tfec (in neural crests and the CHT), whereas flk1:Gal4;UAS:tfec double-transgenic embryos showed ectopic expression in all the vasculature (Figure 4B). Next, we confirmed that the expression of runx1 was normal in flk1:Gal4;UAS:tfec double-positive embryos when compared with single-positive flk1:Gal4 embryos, indicating no change in HSC emergence when tfec is overexpressed in the hemogenic endothelium (Figure 4C). cmyb and mpx expression were normal in flk1:Gal4 single-positive embryos. However, flk1:Gal4;UAS:tfec embryos showed an expansion of cmyb and mpx (Figure 4D-E) consistent with HSC expansion and increased hematopoiesis. Thus, tfec controls definitive hematopoiesis in a non–cell-autonomous manner by affecting the endothelial niche in the CHT.

tfec acts non–cell-autonomously upon HSPCs. (A) Tol2 construct used to generate transgenic zebrafish; schematic is not to scale. (B) ISH for tfec (common probe) at 24 hpf in flk1:Gal4 positive embryos that were either UAS:tfec negative (upper) or positive (lower). (C) ISH for runx1 at 26 hpf in flk1:Gal4-positive embryos that were either UAS:tfec negative (upper) or positive (lower). (D-E) ISH for cmyb and mpx at 4 dpf in flk1:Gal4-positive embryos that were either UAS:tfec negative (upper) or positive (lower).

tfec acts non–cell-autonomously upon HSPCs. (A) Tol2 construct used to generate transgenic zebrafish; schematic is not to scale. (B) ISH for tfec (common probe) at 24 hpf in flk1:Gal4 positive embryos that were either UAS:tfec negative (upper) or positive (lower). (C) ISH for runx1 at 26 hpf in flk1:Gal4-positive embryos that were either UAS:tfec negative (upper) or positive (lower). (D-E) ISH for cmyb and mpx at 4 dpf in flk1:Gal4-positive embryos that were either UAS:tfec negative (upper) or positive (lower).

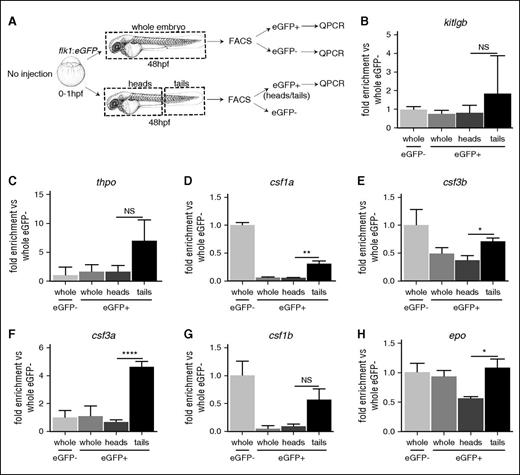

cECs in the CHT express cytokines relevant to HSC expansion and differentiation

After emerging from the aorta, HSCs migrate and colonize the CHT, where they expand. Recent findings emphasized the role of vascular cells in this process,14 and our own experiments emphasize a role for tfec in cECs. We first tried to understand the molecular involvement of cECs in the niche by sorting ECs (flk1:eGFP) from 48 hpf whole embryos or dissected parts (Figure 5A), and measured the expression of hematopoietic cytokines by qPCR in each population compared with flk1-negative cells. Figure 5B-H and supplemental Figure 6A-D show that among all ECs throughout the embryo, cECs specifically expressed kitlgb, thpo, epo, csf1a, csf1b, and csf3a, despite the P value being greater than 0.05 for kitlgb and thpo. However, by comparing cECs with the whole flk1-negative fraction, it appears that cECs could be the main source of kitlgb, thpo, and csf3a in the 48 hpf embryo at the time of HSC colonization. We found no enrichment of kitlga, cxcl12a, and cxcl12b (supplemental Figure 6B-D). Therefore, cECs appear as an important source of cytokines for HSC expansion and differentiation.

Caudal endothelial cells are enriched in niche cytokines. (A) Experimental outline. (B-H) qPCR of hematopoietic niche cytokine expression in FACS-sorted cells outlined in A; data represent biological triplicates. Statistical analysis was completed using an unpaired Student t test, comparing cytokine expression to whole zebrafish. Data represents mean ± SEM. eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; NS, not significant. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .001.

Caudal endothelial cells are enriched in niche cytokines. (A) Experimental outline. (B-H) qPCR of hematopoietic niche cytokine expression in FACS-sorted cells outlined in A; data represent biological triplicates. Statistical analysis was completed using an unpaired Student t test, comparing cytokine expression to whole zebrafish. Data represents mean ± SEM. eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; NS, not significant. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .001.

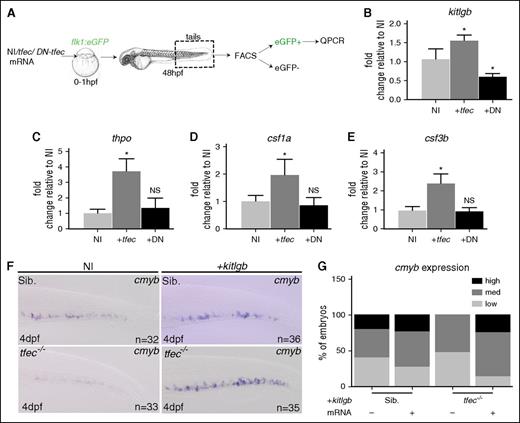

tfec overexpression increases cytokine expression from cECs, resulting in the expansion of definitive hematopoiesis

As we find tfec to be primarily expressed in cECs at 20 to 24 hpf (Figure 1C-D), we therefore investigated its possible role in modulating niche cytokine expression in cECs. Our strategy consisted of measuring transcripts coding for relevant cytokines in cECs after tfec gain or loss of function. As tfec mutants can only be discriminated from their siblings after 4 dpf, when the pigmentation phenotype appears in the retina, we could not use tfec mutants. Instead, we used a dominant-negative tfec (DN-tfec) mRNA to decrease tfec activity. This DN-tfec mRNA only encodes the DNA-binding domain, and is therefore designed to compete with the endogenous tfec, binding to target sites and disrupt tfec-mediated transcriptional activity (supplemental Figure 2B). When we overexpressed hl-ztfec by mRNA injection, we found an increase in kitlgb, thpo, csf1a, csf3b, and epo in sorted cECs (Figure 6A-E; supplemental Figure 7B). Overexpression of DN-tfec mRNA led to a decrease of kitlgb (Figure 6B), but no change in csf3a and cxcl12a expression was detected in any condition (supplemental Figure 7A-D). The modulation of the erythro-myeloid cytokines (csf3b, csf1a, and epo) led to the expected enhancement of myeloid and erythroid development at 4 dpf (supplemental Figure 7E-G).

tfec expression modulates caudal endothelial cytokine expression. (A) Experimental outline. (B-E) qPCR data showing gene expression in FACS-sorted cECs after NI (n = 5 for all), hl-ztfec (+tfec; n = 4 for all, except csf3b, where n = 5) or DN-tfec (+DN; n = 3 for all) injection. Each n represents an average of biological triplicates; experiments were repeated at least 3 times. (F) ISH for cmyb at 4 dpf in WT/tfec+/− embryos or tfec−/− mutant embryos after noninjection (NI) and kitlgb (+kitlgb) injection. (G) Analysis of cmyb expression.

tfec expression modulates caudal endothelial cytokine expression. (A) Experimental outline. (B-E) qPCR data showing gene expression in FACS-sorted cECs after NI (n = 5 for all), hl-ztfec (+tfec; n = 4 for all, except csf3b, where n = 5) or DN-tfec (+DN; n = 3 for all) injection. Each n represents an average of biological triplicates; experiments were repeated at least 3 times. (F) ISH for cmyb at 4 dpf in WT/tfec+/− embryos or tfec−/− mutant embryos after noninjection (NI) and kitlgb (+kitlgb) injection. (G) Analysis of cmyb expression.

Kitlgb mRNA rescues the HSC phenotype observed in tfec mutant embryos

As cKit-Ligand is one of the major cytokines involved in HSC expansion and/or maintenance in mammals, we wanted to test whether kitlgb, which is modulated by tfec, could rescue definitive hematopoiesis in tfec−/− embryos. Injection of kitlgb in WT embryos led to a modest increase of cmyb in the CHT. kitlgb mRNA injection in tfec−/− embryos led to a similar cmyb signal in the CHT (Figure 6F-G). Thus, kitlgb can rescue the expansion of HSCs in the tfec−/− mutants. From these data, we conclude that kitlgb is important for HSCs in the zebrafish model, and that tfec controls kitlgb expression in the vascular niche to promote HSC expansion.

Discussion

The identification of the genetic networks involved in HSC expansion represents a key milestone for regenerative medicine. As many try to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in HSC self-renewal at the cell-autonomous level, our data show that tfec controls HSC expansion at the non–cell-autonomous level. Tfec belongs to the MITF family of transcription factors,37,57 and therefore has been mostly studied in the neural crest cell lineage. We examined carefully the expression pattern of tfec and found that tfec-P2, produced from a distinct transcriptional start site, was abundantly expressed in cECs of the zebrafish embryo between 20 and 36 hpf, a temporal window that precedes the colonization of the CHT by newly produced HSCs.14 We could observe that tfec controls the expression of important cytokines known to expand HSCs, such as kitlgb and thpo.58,59 The expression of kitlgb has already been described at around 24 to 30 hpf in the CHT,60 thus emphasizing the role of cECs in the zebrafish CHT. Most important, our work shows for the first time a role for kitlgb in zebrafish hematopoiesis, as former studies concluded that this signaling pathway was not necessary for the development of HSCs in this model.61 Altogether, the zebrafish HSC niche thus appears as a complex cellular network, entangling ECs as well as stromal cells.14

The production of hematopoiesis-related cytokines by ECs, in particular SCF/kit-ligand, has been described in other models. In the adult mouse, SCF/kitl is necessary for the maintenance of HSCs in the bone marrow. Analysis of the SCF:eGFP reporter mouse ascribed SCF expression to perivascular stromal cells and to ECs.59 Moreover, when SCF was specifically depleted in ECs, the frequency of long-term reconstituting HSCs was severely reduced in competitive assays.59 Similarly, during extramedullary hematopoiesis, SCF produced by ECs is necessary for HSC maintenance in the spleen.62 Finally, recent data indicate the importance of SCF presented by ECs for the survival of DN1 thymocytes.63 Similarly, in the adult mouse, bone marrow ECs can sense inflammatory conditions and produce more GCSF to drive emergency granulopoiesis.64 In the mammalian FL, where HSCs expand,8 ECs might play a similar role. Indeed, fetal HSCs are associated to a vascular niche in the FL,13,14 but so far, the analysis of these ECs has not been thoroughly performed. However, adult liver sinusoidal ECs can provide a suitable environment to sustain hematopoiesis, as they produce SCF, IL-7, and FLT3L.65 Similar observations were made concerning the expansion of human HSCs.66

The novelty of our study resides in the existence of a single transcription factor, tfec-P2, that controls the hematopoietic niche, where HSCs expand. Tfec is specifically expressed in cECs before HSCs colonize the CHT, and could have a role in preparing the niche. Few transcription factors have been described to play such a role in the hematopoietic niche. Ebf2, for example, is crucial to the development of osteoblasts, which will contribute to the HSC niche.33 As well, foxc1 was recently shown to be involved in the expression of cxcl12 from cxcl12-abundant reticulocyte cells in the bone marrow,34 and ATF4 seems to play a similar role in FL stromal cells.35 Further understanding of master regulators of the hematopoietic niche will provide additional and more efficient ways to achieve ex vivo HSC expansion.

Tfec was originally described as a factor that could expand HSCs in a cell-autonomous fashion before its activity was tested in a non–cell-autonomous protocol.39,40 In this latter set of experiments, tfec was overexpressed in NIH3T3, a nonsupportive stroma for hematopoiesis. The NIH3T3-TFEC could maintain HSCs, as cocultured HSCs gained competitive advantage against HSCs cocultured with control NIH3T3 cells. In this study, tfec induced a gene network related to osteoclastogenesis,40 but the physiological role of tfec was completely eluded.

In our study, we show that tfec-P2 is responsible for HSC expansion non–cell-autonomously by modulating cytokine expression in cECs kitlgb and thpo, which are both involved in HSC maintenance,58,59,67 as well as csf3b, which expands HSCs in zebrafish embryos.68 It is unlikely that endogenous tfec expands HSC cell-autonomously, as we never observed tfec expression within the hemogenic endothelium. In addition, overexpression of tfec in the hemogenic endothelium and tfec deletion from the whole embryo did not affect HSC specification. In summary, tfec controls the endothelial CHT niche that is responsible for HSC expansion. Our study provides a new milestone toward the understanding of the molecular events required to expand HSCs ex vivo, aiming at the development of better protocols for regenerative medicine. Indeed, understanding the full spectrum of tfec actions will allow us to better decipher the microenvironmental networks involved in HSC expansion.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Golub for critical reading of the manuscript, S. Lemeille for his help with statistical analyses, S. Costagliola for providing the initial plasmid containing the UAS promoter, and D. Panakova for providing flk1:Gal4 embryos.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Fund (31003A_146527 and 31003A_166515), the “Fondation privee des HUG” (J.Y.B.), and the “Gabriella Giorgi-Cavaglieri Foundation” (J.Y.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.B.M. performed experiments and C.P. provided technical support; C.B.M. and J.Y.B. designed experiments, performed analysis, and prepared the manuscript; and R.J.F. helped with CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Julien Y. Bertrand, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Centre Medical Universitaire, University of Geneva, Rue Michel-Servet 1, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland; e-mail: julien.bertrand@unige.ch.

![Figure 2. tfec overexpression augments the number and proliferation (G2/M phase) of HSPCs in the CHT. (A-B) ISH against cmyb and ikaros (markers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [HSPCs]), prime panels depict the region indicated by the dashed outline box which highlights thymus staining. (C) Schematic indicating approximate imaging area in the tail, as indicated by the black box. (D) Confocal imaging in the CHT of double positive flk1:mCherry/cmyb :GPF embryos in NI or following hl-ztfec (+tfec) injection at 3 and 4 dpf. (F) Confocal imaging in the CHT of triple-positive flk1:eGPF/flk1:Cre/βactinSwitch:DsRed embryos in NI or after hl-ztfec (+tfec) injection at 3 and 4 dpf. (E,G) Analysis of embedded HSPCs at 3 dpf and HSPCs closely associated to endothelial cells at 4 dpf. (H) Imaging schematic at 3 or 4 dpf. (I-N) anti-GFP and pH3 immunostaining at 3 or 4 dpf of either noninjected (NI) or hl-ztfec-injected (+tfec) cmyb:eGPF embryos. (O) Quantification of the number of the pH3+ HSPCs in NI or hl-ztfec-injected embryos at 3 or 4 dpf. Scale bars represent 25 μm; error bars represent SEM. Statistical analysis was completed using an unpaired Student t test, comparing NI with hl-ztfec (+tfec)-injected embryos. NS, no significance. *P < .05; **P < .01. White arrows indicate embedded HSPCs at 3 dpf or closely associated HSPCs at 4 dpf in D and F and represent proliferating HSPCs in I-N.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/128/10/10.1182_blood-2016-04-710137/4/m_1336f2.jpeg?Expires=1769089909&Signature=cbtzKuJu-OTCRkYI~YIeNt0-k87tkUfsRVxWU-3~L-rXDgBUT3fwz1rI90XlXzuPqM-zPbnsbUkriVXoCd-Wi598rdkY4H-X~VDHeROttuBuGWpPNpkdwKXqbBWK2ZjBaV2-A9Y6cA9OqF4fOJUIXAMkmqie2dykXC6W3whKS52kdf-EtMHreFimgQl3MlHyeYCoAyqRnji6GPqAOccxv50fNF0phnkqjqtjGXlCV3LreqNzOxngUl3F3UHqWUxBpSsuPsEFtlcG3ruSxe~~fN7JqQkLLczfMil0-kaMmDaTh7HixrqiAQYIPwUwIH7rTejzxaCmblhyTlUDP5YjZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)