Key Points

Genetic deletion of full-length mouse dematin causes severe abnormalities of erythrocyte shape, membrane stability, and hemolytic anemia.

Dematin is critical for the junctional complex integrity.

Abstract

Dematin is a relatively low abundance actin binding and bundling protein associated with the spectrin–actin junctions of mature erythrocytes. Primary structure of dematin includes a loosely folded core domain and a compact headpiece domain that was originally identified in villin. Dematin’s actin binding properties are regulated by phosphorylation of its headpiece domain by cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase. Here, we used a novel gene disruption strategy to generate the whole body dematin gene knockout mouse model (FLKO). FLKO mice, while born at a normal Mendelian ratio, developed severe anemia and exhibited profound aberrations of erythrocyte morphology and membrane stability. Having no apparent effect on primitive erythropoiesis, FLKO mice show significant enhancement of erythroblast enucleation during definitive erythropoiesis. Using membrane protein analysis, domain mapping, electron microscopy, and dynamic deformability measurements, we investigated the mechanism of membrane instability in FLKO erythrocytes. Although many membrane and cytoskeletal proteins remained at their normal levels, the major peripheral membrane proteins spectrin, adducin, and actin were greatly reduced in FLKO erythrocytes. Our results demonstrate that dematin plays a critical role in maintaining the fundamental properties of the membrane cytoskeleton complex.

Introduction

The long-term survival of mature red blood cells (RBCs) is dependent on the mechanical strength and deformability of its plasma membrane. The RBC membrane is stabilized by a lattice consisting of a defined set of membrane, cytoskeletal, and auxiliary proteins.1-3 The major cytoskeletal components of the junctional complex include actin protofilaments, protein 4.1, adducin, dematin (protein 4.9), tropomyosin, tropomodulin, and p55 (MPP1). It is believed that spectrin–actin junctions are essential for membrane stability and red cell shape3 ; however, the precise mechanism that maintains the integrity of these junctions remains poorly understood.

Dematin is a relatively low abundance cytoskeletal protein located at the spectrin–actin junctions of RBC membrane.4,5 The primary structure of dematin consists of a C-terminal headpiece domain homologous to the villin family of cytoskeletal proteins. The headpiece domain is essential for the actin-bundling activity of dematin, and phosphorylation of the headpiece domain by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase negatively regulates its actin bundling activity in vitro.4,6 To investigate the physiologic role of dematin, we previously generated a knockout mouse model with in-frame deletion of the headpiece domain termed HPKO.7 The HPKO mice showed relatively mild defects of RBC shape and membrane stability.7 This finding is similar to human and mouse models lacking protein 4.1R, adducin, tropomodulin, p55, or glycophorin C that display relatively mild defects in RBC shape and membrane cytoskeleton.8-15 Interestingly, severe defects of RBC shape and membrane stability were observed in mice lacking both dematin headpiece domain and β-adducin (referred to as DAKO), indicating for the first time a synergy between dematin headpiece and β-adducin in maintaining the integrity of RBC membrane junctional complex.16

The modest RBC phenotype observed in the HPKO mice could originate from the normal expression of the core domain of dematin.16 The N-terminal core domain of dematin includes nearly 75% of the full-length protein.17 Therefore, a possibility remained that the observed mild phenotype in the HPKO mice could reflect a partial loss of dematin function. Here, we provide the first hematologic characterization of a mouse model lacking full-length dematin in all tissues. Importantly, our findings unveil dematin as a critical regulator of the spectrin–actin junctions, RBC shape, and membrane stability in vivo. Dematin-null RBC membranes show a substantial loss of spectrin, adducin, and actin by ∼60%, ∼90%, and ∼90%, respectively. To our knowledge, dematin is the first auxiliary cytoskeletal protein at the spectrin–actin junctions whose deletion exhibits a profound detrimental effect on RBC membrane integrity and functions.

Materials and methods

Targeted deletion of full-length dematin

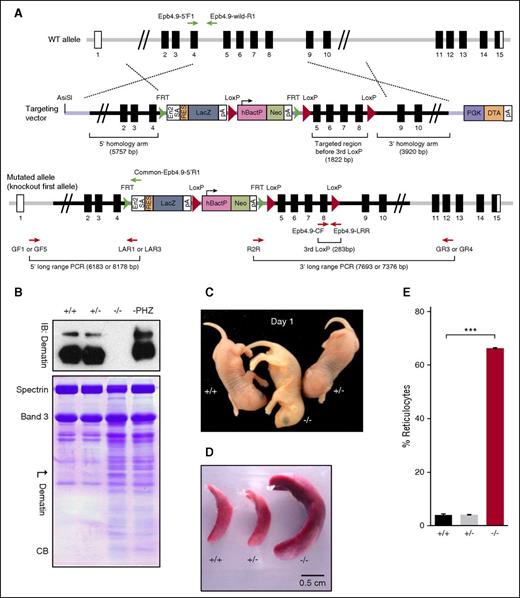

The dematin knockout targeting vector contains a diphtheria toxin A cassette as a negative selection marker (Figure 1A). Correct targeting was confirmed by long-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The heterozygous male and female mice were mated to generate the whole body homozygous, wild-type (WT), and heterozygous animals (see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site, for more details).

Targeted disruption of dematin gene. (A) Targeting vector. Top panel depicts WT mouse dematin (Epb4.9/Epb49/Dmtn/ AI325486) gene. The exon 5 to 8 region is targeted for deletion and the flanking regions upstream (5.7 kb) and downstream (3.9 kb) that constitute the 5′-homology arm and 3′-homology arm of the targeting vector (middle). Lower panel represents the correctly targeted dematin gene designated as knockout-first allele. (B) Western blotting and Coomassie blue–stained SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis profile of RBC ghosts from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), dematin FLKO (−/−) mice, and phenylhydrazine-treated WT (PHZ) erythrocytes/reticulocytes ghosts. Western blotting of RBC ghosts was performed using dematin monoclonal antibody C18 against the core domain of dematin (upper). Similar results were obtained using a polyclonal antibody raised against the full-length dematin. The absence of both 48- and 52-kDa isoforms of dematin in the knockout samples was confirmed with no trace of any residual truncated polypeptide in the expanded gels. In the Coomassie blue–stained SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10%) profile (lower), band 3 was used to normalize equal amounts of total protein. The high reticulocyte count in FLKO samples (∼66%) and PHZ-treated WT (∼60%) samples contributed to distinct profile of membrane polypeptides in the homozygous and WT mice. (C) Pups at day 1. Note the paleness of dematin FLKO (−/−) compared with WT (+/+) and heterozygous (+/−) pups. (D) Splenomegaly observed in dematin FLKO mice. (E) Reticulocyte counts in peripheral blood from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and dematin FLKO (−/−) mice. Reticulocytes were stained by Thiazole orange and counted by flow cytometry. Data were compared by unpaired t test. Mean ± standard deviation (SD): (+/+), n = 3; (+/−), n = 3; (−/−), n = 3. ***P < .0001.

Targeted disruption of dematin gene. (A) Targeting vector. Top panel depicts WT mouse dematin (Epb4.9/Epb49/Dmtn/ AI325486) gene. The exon 5 to 8 region is targeted for deletion and the flanking regions upstream (5.7 kb) and downstream (3.9 kb) that constitute the 5′-homology arm and 3′-homology arm of the targeting vector (middle). Lower panel represents the correctly targeted dematin gene designated as knockout-first allele. (B) Western blotting and Coomassie blue–stained SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis profile of RBC ghosts from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), dematin FLKO (−/−) mice, and phenylhydrazine-treated WT (PHZ) erythrocytes/reticulocytes ghosts. Western blotting of RBC ghosts was performed using dematin monoclonal antibody C18 against the core domain of dematin (upper). Similar results were obtained using a polyclonal antibody raised against the full-length dematin. The absence of both 48- and 52-kDa isoforms of dematin in the knockout samples was confirmed with no trace of any residual truncated polypeptide in the expanded gels. In the Coomassie blue–stained SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10%) profile (lower), band 3 was used to normalize equal amounts of total protein. The high reticulocyte count in FLKO samples (∼66%) and PHZ-treated WT (∼60%) samples contributed to distinct profile of membrane polypeptides in the homozygous and WT mice. (C) Pups at day 1. Note the paleness of dematin FLKO (−/−) compared with WT (+/+) and heterozygous (+/−) pups. (D) Splenomegaly observed in dematin FLKO mice. (E) Reticulocyte counts in peripheral blood from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and dematin FLKO (−/−) mice. Reticulocytes were stained by Thiazole orange and counted by flow cytometry. Data were compared by unpaired t test. Mean ± standard deviation (SD): (+/+), n = 3; (+/−), n = 3; (−/−), n = 3. ***P < .0001.

Reticulocyte deformability assay

The reticulocyte deformability assay was performed as described before.18 Dynamic deformability of reticulocytes was quantified by measuring the average transit velocity of individual reticulocyte while passing through the microfluidic device (see supplemental Methods for more details).

Supplemental methods

Detailed methods on the constructs, hematologic analysis, scanning and transmission electron microscopy, erythrocyte life span, osmotic fragility assay, RBC ghosts, far-western blotting, antibodies, coimmunoprecipitation assay, recombinant fusion proteins, glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assay, and spectrin self-association are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Targeted deletion of full-length dematin

We used a new gene targeting strategy where the null allele of dematin (Epb49) was generated by inserting a trapping cassette between exons 4 and 5 of the dematin (Epb49) locus (Figure 1A). The trapping cassette contains the splice acceptor–internal ribosome entry site–reporter lacZ gene polyadenylation site–hBactP (human β-actin) promoter–neomycin resistance gene–polyadenylation site (Figure 1A). This constitutive null strategy resulted in the truncation of the endogenous dematin transcript in exon 4 (Figure 1A). Exons 5 to 8 of dematin are flanked by the Cre-recombinase targeting loxP sites. This strategy enabled us to generate the whole body full-length dematin-null mouse model as a first step. In the future, the whole body dematin-null mouse model could be used to generate the selective dematin-null allele in a tissue-specific manner. To generate a whole body knockout of dematin, a correctly targeted embryonic stem (ES) cell clone was identified and verified by PCR (supplemental Figure 1A). This clone was injected into blastocysts, and 9 founder lines were obtained where the germline transmission of the null allele was achieved in only 1 founder. Both heterozygous and homozygous dematin-null (FLKO) mice, confirmed by PCR genotyping, were born at the expected Mendelian ratio (supplemental Figure 1B). Immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody against the core domain of dematin confirmed the absence of full-length dematin in the RBC membrane (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate the successful generation of a dematin-null mouse model (FLKO) lacking full-length dematin.

Dematin-null mice display severe hemolytic anemia and splenomegaly

The FLKO mice are viable and fertile. However, paleness was evident at birth in the FLKO mice compared with WT and heterozygous littermates (Figure 1C). At 3 weeks of age, the FLKO mice displayed a modest suppression of weight gain (supplemental Figure 1C-D). A dramatic splenomegaly in 7-week-old FLKO mice was observed, with the average spleen weight being 10-fold higher than in WT littermates (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 5F). The enlarged spleen phenotype persisted in 6- to 8-month-old mice (supplemental Figure 5F,I). No overt defects were observed in the heterozygous mice. Flow cytometry using Thiazole orange showed an ∼17-fold increase in the number of reticulocytes in FLKO mice (Figure 1E), consistent with an increase in compensatory erythropoiesis. Marked reticulocytosis was further corroborated by the increased complexity of polypeptides in the FLKO erythrocyte ghosts by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel electrophoresis (Figure 1B, lower). Consistent with these findings, whole blood analysis of FLKO mice indicated significant reductions of RBC number, hemoglobin, and hematocrit, along with a dramatic increase in the RBC distribution width, indicative of cell size variation in the mutant mice (Table 1). The FLKO mice also showed a two- to threefold increase in the number of circulating white blood cells including lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils (Table 1). Moreover, the darker and enlarged liver morphology in FLKO mice reflected compensatory erythropoiesis (supplemental Figure 5G,I). Together, these results show that FLKO mice display severe anemia and compensatory erythropoiesis in vivo.

Peripheral blood cell counts

| . | +/+ . | +/− . | −/− . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC, K/μL | 8.03 ± 0.72 | 7.95 ± 1.43 | 19.98 ± 1.6* |

| NE, K/μL | 1.29 ± 0.32 | 1.42 ± 0.18 | 2.24 ± 0.5 |

| LY, K/μL | 6.48 ± 0.60 | 6.28 ± 1.53 | 16.49 ± 1.2* |

| MO, K/μL | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.1* |

| EO, K/μL | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.1† |

| BA, K/μL | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.0 |

| NE, % | 16.00 ± 3.29 | 18.38 ± 4.57 | 11.13 ± 1.9 |

| LY, % | 80.76 ± 1.83 | 78.39 ± 5.02 | 82.56 ± 1.5 |

| MO, % | 3.20 ± 1.52 | 2.81 ± 0.32 | 5.65 ± 0.1† |

| EO, % | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.40 | 0.51 ± 0.3 |

| BA, % | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.16 | 0.15 ± 0.2 |

| RBC, M/μL | 10.51 ± 0.33 | 10.89 ± 0.32 | 5.59 ± 0.6* |

| HGB, g/dL | 15.87 ± 0.25 | 15.23 ± 0.46 | 8.90 ± 0.7* |

| HOT, % | 57.57 ± 2.36 | 55.23 ± 2.04 | 33.90 ± 2.4* |

| MCV, fL | 54.77 ± 3.07 | 50.73 ± 1.23 | 60.80 ± 2.2 |

| MCH, Pg | 15.10 ± 0.26 | 14.00 ± 0.35 | 15.97 ± 0.8 |

| MCHC, g/dL | 27.63 ± 1.35 | 27.57 ± 0.25 | 26.23 ± 1.1 |

| RDW, % | 18.03 ± 1.68 | 17.23 ± 0.76 | 35.03 ± 2.7* |

| RETIC, % | 3.92 ± 0.45 | 4.10 ± 0.19 | 66.28 ± 0.2* |

| PLT, K/μL | 816.9 ± 179.2 | 707.0 ± 128.7 | 552.5 ± 131.5† |

| . | +/+ . | +/− . | −/− . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC, K/μL | 8.03 ± 0.72 | 7.95 ± 1.43 | 19.98 ± 1.6* |

| NE, K/μL | 1.29 ± 0.32 | 1.42 ± 0.18 | 2.24 ± 0.5 |

| LY, K/μL | 6.48 ± 0.60 | 6.28 ± 1.53 | 16.49 ± 1.2* |

| MO, K/μL | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.1* |

| EO, K/μL | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.1† |

| BA, K/μL | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.0 |

| NE, % | 16.00 ± 3.29 | 18.38 ± 4.57 | 11.13 ± 1.9 |

| LY, % | 80.76 ± 1.83 | 78.39 ± 5.02 | 82.56 ± 1.5 |

| MO, % | 3.20 ± 1.52 | 2.81 ± 0.32 | 5.65 ± 0.1† |

| EO, % | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.40 | 0.51 ± 0.3 |

| BA, % | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.16 | 0.15 ± 0.2 |

| RBC, M/μL | 10.51 ± 0.33 | 10.89 ± 0.32 | 5.59 ± 0.6* |

| HGB, g/dL | 15.87 ± 0.25 | 15.23 ± 0.46 | 8.90 ± 0.7* |

| HOT, % | 57.57 ± 2.36 | 55.23 ± 2.04 | 33.90 ± 2.4* |

| MCV, fL | 54.77 ± 3.07 | 50.73 ± 1.23 | 60.80 ± 2.2 |

| MCH, Pg | 15.10 ± 0.26 | 14.00 ± 0.35 | 15.97 ± 0.8 |

| MCHC, g/dL | 27.63 ± 1.35 | 27.57 ± 0.25 | 26.23 ± 1.1 |

| RDW, % | 18.03 ± 1.68 | 17.23 ± 0.76 | 35.03 ± 2.7* |

| RETIC, % | 3.92 ± 0.45 | 4.10 ± 0.19 | 66.28 ± 0.2* |

| PLT, K/μL | 816.9 ± 179.2 | 707.0 ± 128.7 | 552.5 ± 131.5† |

Peripheral blood cell counts of WT (+/+, n = 3), heterozygous (+/−, n = 3), and dematin FLKO (−/−, n = 3). Values are given as mean ± SD. Unpaired t test. BA, basophils; EO, eosinophils; HCT, hematocrit; HGB, hemoglobin; LY, lymphocytes; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MO, monocytes, NE, neutrophils; PLT, platelets; RBC, red blood cells; RDW, red cell distribution width; RETIC, reticulocytes; WBC, white blood cells.

P < .001.

P < .05.

Primitive and definitive erythropoiesis in dematin-null mice

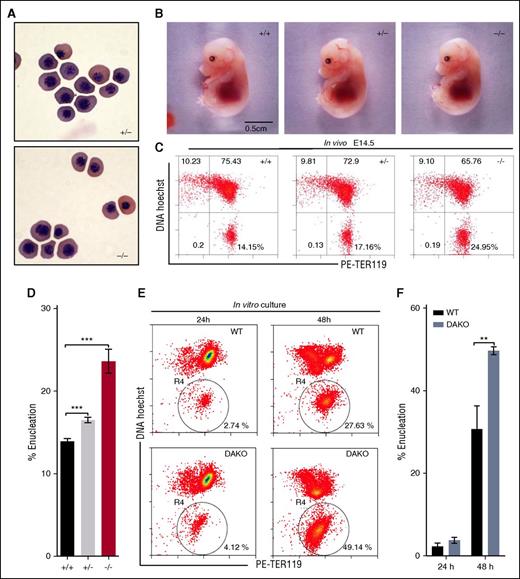

To determine the potential functional role of dematin in erythropoiesis, we first evaluated the status of primitive erythropoiesis in FLKO mice. The morphology of nucleated erythroid cells at day E13.5, which represents primitive erythropoiesis, was unaltered in FLKO mice, suggesting that dematin may not play any discernible functional role in primitive erythropoiesis (Figure 2A). Next we examined the impact of dematin knockout on definitive erythropoiesis. The overall morphology of FLKO embryos at day E14.5, when definitive erythropoiesis sets in, appeared to be normal (Figure 2B). Because enucleation is an integral part of definitive erythropoiesis, we examined the status of erythroblast enucleation during fetal liver erythropoiesis in vivo. Nearly ∼90% of fetal liver cells at E14.5 represent erythroid precursors. Therefore, fetal liver cells were harvested at E14.5 from heterozygous parents, stained with the erythroid-specific TER119 and cell-permeable DNA Hoechst 33342, and quantified by flow cytometry (Figure 2C). In vivo erythroblasts enucleation (HoechstlowTER119high) was significantly increased in FLKO and heterozygous embryos compared with WT mice (Figure 2C-D), suggesting premature enucleation in the mutant mice. This finding suggests that increased enucleation in FLKO embryos is unlikely to be caused by the membrane instability because the heterozygous mice displaying nearly normal RBC membrane properties (Figure 3B) also show enhanced enucleation (Figure 2C-D). In addition, we examined the status of erythroblasts enucleation in vitro from the DAKO mice.16 The DAKO mice show more severe anemia than either the HPKO mice or β-adducin–null mice.7,14,15 Again, the erythroblasts enucleation was significantly enhanced in the DAKO mice (Figure 2E-F). It is noteworthy that RBCs harvested from band 3 knockout mice or ankyrin nb/nb mice are hematologically fragile and prone to vesiculation and fragmentation. However, fetal liver erythroblasts harvested from these mice did not show any defects in the enucleation efficiency.19

Impact of dematin deficiency on primitive and definitive erythropoiesis. (A) Primitive erythrocytes (Cytospin) from peripheral blood of embryos at E13.5. Wright-Giemsa stain. Shown at ×60 original magnification. (B) Morphology of intact embryos at E14.5 endowed with definitive erythropoiesis. (C) Quantification of mouse fetal erythroblast enucleation in vivo by flow cytometry. The percentage of enucleated cells is indicated in the lower right quadrant. (D) Statistical analysis of erythroblast enucleation in vivo (E14.5). Unpaired t test, mean ± SD, ***P < .001. WT, n = 5; HET, n = 5; FLKO, n = 3. (E) Analysis of mouse fetal liver erythroblast enucleation in vitro. TER119 negative erythroid progenitor cells of E14.5 fetal liver cells from WT and DAKO were isolated and quantified after 24 and 48 hours in culture by flow cytometry using Hoechst 33342 and PE-TER119. Circled R4 region represents the enucleated fraction (HoechstlowTER119high). (F) Percentage of enucleated cells is indicated. Unpaired t test, **P < .01. Mean ± SD; WT, n = 3; DAKO, n = 3.

Impact of dematin deficiency on primitive and definitive erythropoiesis. (A) Primitive erythrocytes (Cytospin) from peripheral blood of embryos at E13.5. Wright-Giemsa stain. Shown at ×60 original magnification. (B) Morphology of intact embryos at E14.5 endowed with definitive erythropoiesis. (C) Quantification of mouse fetal erythroblast enucleation in vivo by flow cytometry. The percentage of enucleated cells is indicated in the lower right quadrant. (D) Statistical analysis of erythroblast enucleation in vivo (E14.5). Unpaired t test, mean ± SD, ***P < .001. WT, n = 5; HET, n = 5; FLKO, n = 3. (E) Analysis of mouse fetal liver erythroblast enucleation in vitro. TER119 negative erythroid progenitor cells of E14.5 fetal liver cells from WT and DAKO were isolated and quantified after 24 and 48 hours in culture by flow cytometry using Hoechst 33342 and PE-TER119. Circled R4 region represents the enucleated fraction (HoechstlowTER119high). (F) Percentage of enucleated cells is indicated. Unpaired t test, **P < .01. Mean ± SD; WT, n = 3; DAKO, n = 3.

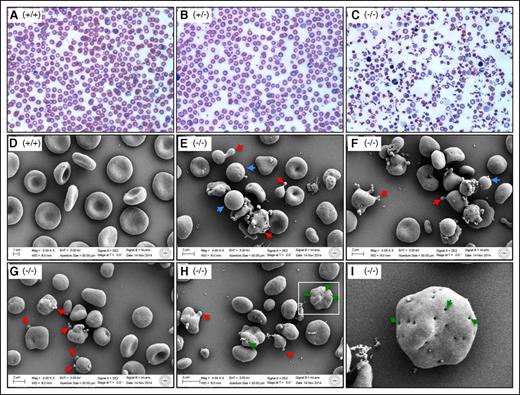

Aberrant erythrocyte morphology. (A-C) Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral blood smears from 3-week-old mice. Shown at ×60 original magnification. (D-I) Scanning electron microscopy of peripheral blood cells of 18-week-old mice. Shown at ×4000 original magnification. Blue arrows show spherocytes; red arrows show extensive microcytic vesiculation and protruding structures; and green arrows show many invaginations in FLKO erythrocytes/reticulocytes. (I) An enlarged view of the rectangle area shown in H to highlight the presence of multiple invaginations in a single cell. (+/+), WT; (+/−), heterozygous; (−/−), dematin FLKO.

Aberrant erythrocyte morphology. (A-C) Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral blood smears from 3-week-old mice. Shown at ×60 original magnification. (D-I) Scanning electron microscopy of peripheral blood cells of 18-week-old mice. Shown at ×4000 original magnification. Blue arrows show spherocytes; red arrows show extensive microcytic vesiculation and protruding structures; and green arrows show many invaginations in FLKO erythrocytes/reticulocytes. (I) An enlarged view of the rectangle area shown in H to highlight the presence of multiple invaginations in a single cell. (+/+), WT; (+/−), heterozygous; (−/−), dematin FLKO.

Dematin is essential for erythrocyte shape and life span

The accelerated erythroblast enucleation in FLKO mice may shorten the cell maturation process, thus resulting in RBC membrane structure and function defects. To test this model, we first examined RBC shape in the peripheral blood. Evidence of significant anisocytosis, microcytosis, macrocytosis, and polychromasia is indicative of RBC size variation in the FLKO mice (Figure 3). Similarly, RBC abnormalities such as poikilocytes, acanthocytes, schistocytes, spherocytes, and fragmented cells are consistent with severe hemolytic anemia in the FLKO mice (supplemental Figure 2). The unusually high reticulocytosis in FLKO mice (Figure 1E) is consistent with defects in membrane stability and premature erythroblast enucleation. Next, we examined RBC morphology by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Consistent with the Giemsa staining, SEM showed a vast variation of RBC shape and size in FLKO mice (Figure 3). Numerous spherocytes (Figure 3, blue arrows), microcytes, vesicles, and protruding structures (Figure 3, red arrows) were observed in FLKO mice. Interestingly, we observed many pit-like invaginations in the FLKO RBC surface (Figure 3I, green arrows) compared with WT mice, as well as phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-treated WT mice with high reticulocytosis (supplemental Figure 3). Although the mechanistic basis of these invaginations or pits is not yet known, to our knowledge no such invaginations in erythroid cells have been reported before in either hemolytic anemia patients or animal models displaying severe anemia.20,21

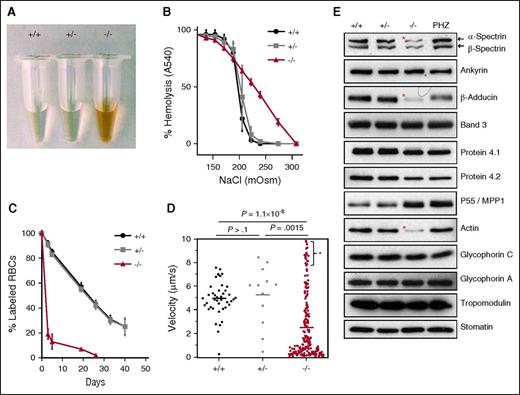

Abnormalities of RBC shape suggested the existence of membrane instability and shortened life span in FLKO mice. Extensive intravascular hemolysis in vivo was evident by the presence of free hemoglobin in the plasma of FLKO mice (Figure 4A). To determine the effect of dematin loss on RBC membrane stability under hypotonic conditions, in vitro hemolysis was measured (Figure 4B). In contrast to the expected RBC lysis within a narrow NaCl osmolarity window in the WT and heterozygous mice, the FLKO cells started to lyse at a modest reduction of NaCl osmolarities (275-225 mOsm NaCl) and displayed a linear lysis curve on progressive reduction of osmolarities (Figure 4B). Under conditions where >95% of WT and heterozygous RBCs were intact, >50% of FLKO cells lysed, indicating a greatly reduced ability of FLKO cells to withstand osmotic stress (Figure 4B). Due to high reticulocytosis in the dematin FLKO mice, the cell population continuously lyse in a linear fashion with increased osmotic stress in contrast to WT RBCs that can withstand osmotic stress to a certain point and then rupture (Figure 4B). To determine the RBC life span, we measured RBC half-life in vivo by N-hydroxysuccinimide–biotin labeling and flow cytometry (Figure 4C). The biotin-labeled RBCs were identified and quantified by the “pulse and chase” method. A 7-week chase analysis indicated reduction of erythrocyte/reticulocyte half-life from 22 days in WT and heterozygous mice to <3 days in FLKO mice (Figure 4C). These results show that normal RBC shape, membrane stability, and life span are critically dependent on the presence of full-length dematin.

Hematologic characterization. (A) Intravascular hemolysis in dematin FLKO mice. (B) Osmotic fragility analysis. Means ± SD, n = 3 for each genotype. (C) In vivo life span measurement. A dramatic reduction of intact surviving erythrocytes/reticulocytes was observed in FLKO mice. Means ± SD; (+/+), n = 4; (+/−), n = 4; (−/−), n = 5. (D) Dynamic deformability of reticulocytes. Data indicate a marked reduction of dynamic deformability in FLKO reticulocytes. The high velocity fraction (*) presumably represents microcytic vesicles and fragments from labeled reticulocytes. Each dot represents 1 labeled reticulocyte, and the solid bar represents the average derived from 3 animals of each genotype. Data were compared using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. (E) Western blot analysis. Membrane proteins from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), dematin FLKO (−/−), and PHZ-treated WT erythrocytes/reticulocytes ghosts. Protein loading was normalized by band 3. Note that the PHZ treatment causes a slight shift in the mobility of adducin and dematin bands (Figure 1B). *Significant protein deficiency.

Hematologic characterization. (A) Intravascular hemolysis in dematin FLKO mice. (B) Osmotic fragility analysis. Means ± SD, n = 3 for each genotype. (C) In vivo life span measurement. A dramatic reduction of intact surviving erythrocytes/reticulocytes was observed in FLKO mice. Means ± SD; (+/+), n = 4; (+/−), n = 4; (−/−), n = 5. (D) Dynamic deformability of reticulocytes. Data indicate a marked reduction of dynamic deformability in FLKO reticulocytes. The high velocity fraction (*) presumably represents microcytic vesicles and fragments from labeled reticulocytes. Each dot represents 1 labeled reticulocyte, and the solid bar represents the average derived from 3 animals of each genotype. Data were compared using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. (E) Western blot analysis. Membrane proteins from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), dematin FLKO (−/−), and PHZ-treated WT erythrocytes/reticulocytes ghosts. Protein loading was normalized by band 3. Note that the PHZ treatment causes a slight shift in the mobility of adducin and dematin bands (Figure 1B). *Significant protein deficiency.

Dematin regulates reticulocyte deformability

The short life span of FLKO RBCs and reticulocytes could be a consequence of either membrane fragility or inability to withstand deformation in circulation or both. Because the presence of reticulocytes accounts for a much larger fraction of cells within the RBC gate (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 2F), and the bloodstream clearance of reticulocytes is not precisely defined, other mechanisms may also contribute to the rapid clearance of FLKO reticulocytes. The presence of a mixed population of erythroid cells of varying size in FLKO mice precluded the use of conventional ektacytometry to measure cell deformability at the bulk level. Therefore, we examined the deformability of WT, heterozygous, and FLKO reticulocytes directly by a microfluidic device that is capable of measuring population-wide single cell deformability by probing the transit velocity of reticulocytes in a biomimetic microenvironment.22 Blood samples were stained with Thiazole orange, which specifically labels reticulocytes, thus permitting a direct measurement of transit velocity of reticulocytes as they travel through the microfluidic device with repeated bottleneck structures simulating the in vivo microcirculatory system.22 The velocity (ie, deformability) of FLKO reticulocytes was significantly reduced (2.48 µm/s in the FLKO vs 5 µm/s in the WT and heterozygous, P = 1.1 × 10−8; Figure 4D). We also observed a subpopulation of reticulocytes from FLKO mice displaying an extremely fast velocity consistent with the presence of smaller reticulocytes as observed in the new methylene blue staining (supplemental Figure 2F). Cellular morphology observed in the blood smears from 7-week-old mice was relatively improved compared with 3-week-old mice. The improved morphology might reflect splenic trapping of abnormal erythrocytes and reticulocytes in vivo (supplemental Figure 2B,D). These results suggest that reduced deformability and subsequent splenic trapping is a potential mechanism for the short half-life of FLKO erythrocytes and reticulocytes.

Spectrin–actin–adducin complex at the RBC membrane requires dematin

To investigate the underlying mechanism of extreme RBC membrane fragility in FLKO mice, we examined the status of major membrane proteins in RBC ghosts. Because FLKO mice exhibit high reticulocytosis, normalization of total membrane protein content was achieved by equal loading of band 3 (Figure 4E). Surprisingly, the abundance of many known membrane-associated proteins was unchanged in the FLKO erythrocyte/reticulocyte ghosts (Figure 4E). In contrast, there was a substantial reduction of spectrin, adducin, and actin in the FLKO ghosts. When normalized against band 3, the 3 proteins were reduced by ∼60%, ∼90%, and ∼90%, respectively, in FLKO ghosts (Figure 4E). These results show that the normal accumulation/retention of actin, spectrin, and adducin is critically dependent on dematin in the RBC membrane. To eliminate the possibility that loss of the spectrin–actin–adducin complex could be triggered by the disruption of spectrin tetramer–dimer equilibrium at steady state,23 the spectrin tetramer was isolated from FLKO, WT, heterozygous, and PHZ-treated WT mice. The PHZ treatment was necessary to achieve high reticulocytosis (∼60%) in WT mice. Spectrin tetramer fraction from all samples readily dissociated into dimers at 37°C (Figure 5A-B), indicating that dematin does not maintain spectrin tetramer–dimer equilibrium and instead may play a unique role in retaining spectrin tetramer at the plasma membrane in association with actin and adducin.

Mechanism of weakened erythrocyte junctional complex. (A) Fairbanks gel electrophoresis (4% acrylamide gel, denaturing conditions) of ghosts. Band 3 was used to normalize protein loading. (B) Spectrin dimer-tetramer equilibrium analysis. Spectrin tetramers were extracted at low ionic strength buffer at 0°C (on ice; upper gel panel) and converted to dimers at 37°C (lower gel panel). Dimer-tetramer content was analyzed by Fairbanks gel electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions. Note that the spectrin tetramers were dissociated (>95%) into dimers in dematin FLKO (−/−) sample, indicating that dematin loss does to affect spectrin self-association under these conditions. “T” indicates position of spectrin tetramers. “D” indicates position of spectrin dimers. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of dematin using Flag-β-adducin. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding dematin and Flag-β-adducin (Add2) or empty vector. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-Flag agarose beads. Dematin amount in the immune-complex was normalized by western blotting using the anti-dematin polyclonal antibody. (D,F,G) GST pull-down assays. T, Trx tag alone; F, Trx-dematin-rD full length; S, Trx-dematin-rD-S381E mutant; H, Trx-Dematin-headpiece domain; C, Trx-Dematin-core domain-rD; G, GST tag alone; A, GST-β-Adducin; β, GST-β-Spectrin-actin-binding domain1-2; α, GST-α-Spectrin-20-21-EF. Equal loading of GST or GST fusion proteins was confirmed by Coomassie staining. Black dots represent phosphorylation-mimic mutation where serine-381 was changed to glutamic acid (E) in the dematin headpiece domain. Dematin-S381E change promotes dematin headpiece interaction with the core domain. (E) Dematin far-western blotting. Human erythrocyte ghosts were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and blots were incubated with purified human dematin alone or in the presence of purified spectrin. No signal was detected with preimmune serum (lane 1). Anti-dematin polyclonal antibody detected endogenous 48- and 52-kDa polypeptides of dematin (lanes 2 and 3), as well as purified dematin bound to β-spectrin (lane 2). Note that dematin binding to immobilized β-spectrin was eliminated by soluble spectrin (lane 3). Dematin did not bind to α-spectrin under these conditions.

Mechanism of weakened erythrocyte junctional complex. (A) Fairbanks gel electrophoresis (4% acrylamide gel, denaturing conditions) of ghosts. Band 3 was used to normalize protein loading. (B) Spectrin dimer-tetramer equilibrium analysis. Spectrin tetramers were extracted at low ionic strength buffer at 0°C (on ice; upper gel panel) and converted to dimers at 37°C (lower gel panel). Dimer-tetramer content was analyzed by Fairbanks gel electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions. Note that the spectrin tetramers were dissociated (>95%) into dimers in dematin FLKO (−/−) sample, indicating that dematin loss does to affect spectrin self-association under these conditions. “T” indicates position of spectrin tetramers. “D” indicates position of spectrin dimers. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of dematin using Flag-β-adducin. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding dematin and Flag-β-adducin (Add2) or empty vector. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-Flag agarose beads. Dematin amount in the immune-complex was normalized by western blotting using the anti-dematin polyclonal antibody. (D,F,G) GST pull-down assays. T, Trx tag alone; F, Trx-dematin-rD full length; S, Trx-dematin-rD-S381E mutant; H, Trx-Dematin-headpiece domain; C, Trx-Dematin-core domain-rD; G, GST tag alone; A, GST-β-Adducin; β, GST-β-Spectrin-actin-binding domain1-2; α, GST-α-Spectrin-20-21-EF. Equal loading of GST or GST fusion proteins was confirmed by Coomassie staining. Black dots represent phosphorylation-mimic mutation where serine-381 was changed to glutamic acid (E) in the dematin headpiece domain. Dematin-S381E change promotes dematin headpiece interaction with the core domain. (E) Dematin far-western blotting. Human erythrocyte ghosts were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and blots were incubated with purified human dematin alone or in the presence of purified spectrin. No signal was detected with preimmune serum (lane 1). Anti-dematin polyclonal antibody detected endogenous 48- and 52-kDa polypeptides of dematin (lanes 2 and 3), as well as purified dematin bound to β-spectrin (lane 2). Note that dematin binding to immobilized β-spectrin was eliminated by soluble spectrin (lane 3). Dematin did not bind to α-spectrin under these conditions.

Dematin participates in binary interactions with adducin and spectrin

Our previous studies localized both dematin and adducin at the RBC junctional complex.5 Here we examined a direct physical association between dematin and adducin. First, ectopically expressed dematin was coimmunoprecipitated with Flag-tagged β-adducin expressed in HEK 293T cells. Immunoblotting using an anti-dematin monoclonal antibody confirmed the presence of the dematin–adducin complex (Figure 5C). A direct interaction between dematin and β-adducin was demonstrated using GST pulldown assays and purified dematin (Figure 5D). Phosphorylation of dematin headpiece domain at serine 381 (S381) is known to promote its affinity to the core domain and abrogates actin bundling activity.24 The GST–β-adducin pulled down full-length dematin with or without a S381E mutation, as well as the core and headpiece domains of dematin (Figure 5D). The serine-381 change to glutamic acid (E) reflects the phosphorylation-mimic mutant of dematin, as shown previously.24 These data suggest that multiple domains of dematin contribute to its interaction with β-adducin (Figure 5D).

Far-western immunoblotting with native dematin and RBC membrane proteins was used to screen candidate proteins that may link the dematin–adducin complex to the plasma membrane. This approach revealed a direct interaction between native dematin and β-spectrin (Figure 5E). The interaction between immobilized β-spectrin and native dematin was abolished in the presence of soluble native spectrin (Figure 5E, lane 3). Conversely, soluble native dematin did not bind to immobilized α-spectrin under the same experimental conditions (Figure 5E, lane 2), likely due to inappropriate folding of the α-spectrin after the denaturation–renaturation process. A direct dematin–spectrin interaction was further confirmed by the GST-pull down assays using recombinant dematin, mini-β-spectrin, and mini-α-spectrin constructs (Figure 5F-G). The mini-β-spectrin containing the actin-binding domain and the first 2 repeats25 pulled down full-length recombinant dematin (Figure 5F, lane 9), full-length dematin with a S381E mutation within the headpiece domain (Figure 5F, lane 11), and the core domain of dematin (Figure 5F, lane 15). The mini-β-spectrin did not bind to the headpiece domain of dematin under these conditions (Figure 5F, lane 13), although a weak affinity interaction between mini-β-spectrin and the headpiece domain of dematin cannot be completely ruled out at this stage. Similarly, the mini-α-spectrin bound full-length recombinant dematin (Figure 5G, lane 9), full-length dematin carrying the S381E mutation (Figure 5G, lane 11), and the core domain of dematin (Figure 5G, lane 15). This assay detected a relatively weak interaction between mini-α-spectrin and the headpiece domain of dematin (Figure 5G, lane 13). This finding is consistent with a previous demonstration that dematin binds to a mini-spectrin construct containing both α and β subunits, and this interaction is sensitive to phosphorylation of dematin by cAMP-dependent protein kinase.26 As mentioned in the previous study,26 the biochemical interaction of dematin with actin and spectrin and its sensitivity to phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase have been previously documented.4,17 In our study, we also noticed a significant reduction in the protein–protein interaction between spectrin and the full-length dematin-S381E mutation (Figure 5F,G, lane 11). This finding could be explained by the recent demonstration that the headpiece domain of dematin (S381E) strongly interacts with the core domain of dematin.24 The weakened interaction observed between spectrin and full-length dematin (S381E) is likely due to the internal competition by the headpiece domain with the core domain of dematin.

Dematin regulates structural integrity of the RBC membrane cytoskeleton

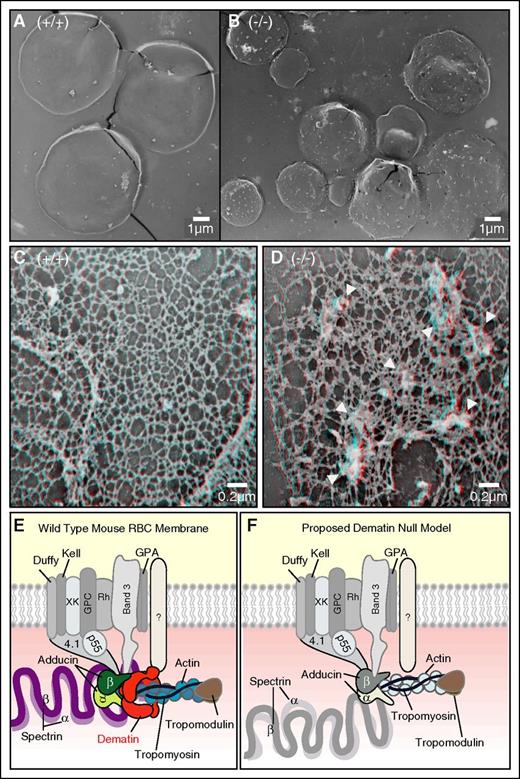

As discussed above, and shown in Figure 3, RBCs from dematin FLKO lack flattened biconcave shape compared with WT mice (Figure 6A-B). The structure of the FLKO erythrocytes and reticulocytes is also replete with small invaginations that are suggestive of coated pits. Mature erythrocytes and reticulocytes are known to contain the machinery for the formation of coated pits and vesicles,27,28 although surface replicas have not revealed many sites of pit formation in the mature cells. The abnormal morphology and high number of pit structures on erythrocytes from the FLKO mice suggested gross changes in the underlying spectrin–actin membrane skeleton. The high-resolution structure of the membrane skeleton was therefore evaluated. Representative membrane skeletons from WT (Figure 6C) and FLKO cells (Figure 6D) are shown. In these stereo images (view with blue/red glasses), the underlying membrane skeleton from the FLKO cells is grossly abnormal (Figure 6D). Compared with WT erythrocyte skeletons that are flat lattices composed of triangular spectrin–actin connections, the FLKO skeletons show many focal aggregates of components (arrowheads), and both enlarged and compressed pores in the membrane skeleton (Figure 6D). Whether these distortions in the spectrin–actin structure result from enhanced endocytosis or alterations in the spectrin–actin connection to the membrane in the absence of dematin is not yet known. However, in comparison with the membrane skeletons from other erythrocyte models lacking spectrin–cytoskeleton proteins, particularly components of the junctional complex, dematin FLKO skeletons show the greatest amount of disruption (Figure 6D). Together, these findings demonstrate that the deletion of full-length dematin alone is sufficient to cause a precipitous disruption of erythrocyte membrane skeleton despite the presence of other known adaptor proteins from the junctional complex.

Transmission electron microscopy of erythrocyte membrane skeleton. Dematin FLKO erythrocytes are immature and have grossly deranged membrane skeletons. Comparison of the surface topology of (A) WT and (B) dematin FLKO erythrocytes. The structure of dematin FLKO erythrocytes is replete with invaginations that correspond to coated pits. (A) WT mature erythrocytes have a featureless surface. The skeleton underlying the membrane of dematin FLKO erythrocytes is abnormal, having many focal disruptions in the (D) spectrin-based skeleton compared with the (C) WT membrane skeleton. Bars correspond to 0.2 μm. Statistical analysis of the pore size was performed. Mann-Whitney test, 2-tailed, P < .0001. (E-F) Proposed model of dematin–membrane complex. Dematin and adducin coanchor the spectrin–actin complex to the erythrocyte plasma membrane. (E) Note that the mouse erythrocyte membrane does not contain any glucose transporter-1 (GLUT1), and therefore the receptor that links dematin to the membrane is not yet known. (F) Deletion of dematin causes rupture of the linkage between the spectrin–actin complex and the plasma membrane due to the secondary loss of adducin, resulting in concomitant decrease of both spectrin and actin at the junctional complex.

Transmission electron microscopy of erythrocyte membrane skeleton. Dematin FLKO erythrocytes are immature and have grossly deranged membrane skeletons. Comparison of the surface topology of (A) WT and (B) dematin FLKO erythrocytes. The structure of dematin FLKO erythrocytes is replete with invaginations that correspond to coated pits. (A) WT mature erythrocytes have a featureless surface. The skeleton underlying the membrane of dematin FLKO erythrocytes is abnormal, having many focal disruptions in the (D) spectrin-based skeleton compared with the (C) WT membrane skeleton. Bars correspond to 0.2 μm. Statistical analysis of the pore size was performed. Mann-Whitney test, 2-tailed, P < .0001. (E-F) Proposed model of dematin–membrane complex. Dematin and adducin coanchor the spectrin–actin complex to the erythrocyte plasma membrane. (E) Note that the mouse erythrocyte membrane does not contain any glucose transporter-1 (GLUT1), and therefore the receptor that links dematin to the membrane is not yet known. (F) Deletion of dematin causes rupture of the linkage between the spectrin–actin complex and the plasma membrane due to the secondary loss of adducin, resulting in concomitant decrease of both spectrin and actin at the junctional complex.

Discussion

Dematin is a widely expressed member of the villin family of cytoskeletal proteins.17 Unlike villin, dematin’s actin bundling property is regulated by phosphorylation mediated by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase.4,29 Dematin regulates calcium mobilization, RhoA activity, cell shape, and cell migration in nonerythroid cells.30-32 Despite much effort, the physiologic function of RBC dematin remains poorly understood. Gene targeting and global transcript analysis revealed dematin as a major target of EKLF,33,34 an erythroid-specific transcription factor that is essential for the regulation of definitive erythropoiesis.35 These studies suggested a functional role of dematin in late erythropoiesis, consistent with earlier studies on dematin expression during erythropoiesis.26,36 Our results show that dematin functions as a negative regulator of erythroblast enucleation without affecting primitive erythropoiesis (Figure 2). This finding is consistent with the absence of nucleated erythroid precursors in the peripheral blood of FKLO mice. Whether a functional role of dematin in erythroblast enucleation requires the reorganization of actin bundles, disruption of the membrane skeleton interface, phosphorylation-mediated conformational changes, and signaling downstream of the actin cytoskeleton are questions that will be experimentally feasible using the FLKO animal model described here (Figure 1).

The dematin FLKO mouse model revealed an essential and nonredundant function of dematin as a key component of the junctional complex. In dematin FLKO mice, the secondary loss of adducin, actin, and spectrin at the junctional complex and subsequent disruption of cell shape and membrane integrity strongly argue for an indispensable role of dematin in the organization and maintenance of the erythrocyte junctional complex. Remarkably, the overall hematological phenotype of dematin FLKO mice is as severe, if not more, as the band 3 and ankyrin-null mouse models.20,21,37,38 These observations suggest that the attachment of spectrin tetramer to the plasma membrane is critically dependent upon the presence of intact dematin in the erythrocyte membrane. In the FLKO mice, the loss of the membrane spectrin–actin complex is substantially greater than the HPKO model we reported earlier.7 Because nearly 90% of adducin is missing from the FLKO erythrocyte ghosts, adducin may help to coanchor and stabilize the spectrin–actin complex to the membrane. However, its function appears to be completely reliant on the presence of dematin at the junctional complex. One way to explain these findings is that an anchoring activity is partially lost in the HPKO mice, but the loss is at least partially overcome by the formation of a complex between the residual core domain of dematin and adducin. The anchoring activity is preserved by dematin, thus accounting for the relatively mild hematologic phenotype observed in adducin-deficient mice.10,15 In contrast, adducin lacks the ability to fully complement other activities of dematin, thus accounting for the strong phenotype seen in dematin FLKO model. Therefore, the association of adducin with the RBC membrane is strictly dependent on the presence of full-length dematin.

The ability of dematin to function as an anchor for the junctional complex would suggest its biochemical interactions with multiple proteins associated with the junctional complex. Evidence showing direct binding of dematin with adducin, actin,39 and spectrin is consistent with its role as an anchor of these proteins to the plasma membrane (Figure 5). The mechanism of dematin and adducin mediated linkage of the junctional complex to the membrane remains poorly understood. Adducin is known to bind band 3 in both human and mouse RBC membranes.40 Similarly, dematin and adducin have been shown to bind glucose transporter-1, which is present only in the human erythrocyte membranes.41,42 Therefore, a possibility remains that multiple factors link the junctional complex to the membrane via dematin and adducin. For example, a modest reduction of CD47 was observed in FLKO RBCs and reticulocytes (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Although the precise reason for this reduction of CD47 is not yet known, the modest reduction of CD47 could be accounted for by the relatively smaller cell size and surface area in dematin null RBC/reticulocyte population as assessed by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 4E-F). Similarly, a marked increase of phosphatidylserine exposure was observed in FLKO erythrocytes but not in reticulocytes (supplemental Figure 4C-D). A simple explanation could be that a dramatic reduction in the membrane instability triggered the phosphatidylserine exposure, thus contributing to short life span observed in dematin null mice.

Our proposed model (Figure 6E-F) suggests that dematin, along with adducin, functions as the main anchor in attaching the spectrin–actin junctions to the erythrocyte plasma membrane. Considering the clinical importance of protein 4.1 in hereditary elliptocytosis and RBC membrane stability,9,43 it is conceivable that protein 4.1 might be able to hold the remaining residual junctional complex in the dematin-null RBC membranes. Given the relatively mild effects of glycophorin C deficiency on RBC shape and membrane stability,44 protein 4.1 is likely to anchor the junctional complex via multiple membrane receptors. In any event, future identification of the receptors that anchor the junctional complex to the membrane will be of high physiological significance since their interactions with dematin and adducin would provide a regulatory mechanism for the maintenance of erythrocyte shape and membrane stability. It is reasonable to speculate that the full spectrum of the biological functions of adducin was missed because of the presence of dematin in the adducin mutant mice. Generation of dematin FLKO mouse model with conditional potential will allow evaluation of dematin function in a tissue-specific manner in diverse settings where dematin is known to play a role such as hemolytic anemia, malaria, hemostasis, adhesion, and cell migration pathways.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janis Lem of Tufts Transgenic Facility for generously providing technical advice and training during the ES cell culture, electroporation, and colony selection protocols; Stuart Orkin of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, for providing access to their National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases–supported Transgenic Center; James McKnight (Boston University) for sharing constructs carrying dematin point mutations; Sandra Harper and David W. Speicher of the Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, for providing spectrin constructs; and Anlee Krupp and Elbara Ziade (Boston University Photonic Center) for the training of scanning electron microscope; David Liu (HDM Systems Corporation) and Ronald Dubreuil (University of Illinois at Chicago) for technical assistance and advice at various stages of this project; and Donna-Marie Mironchuk for the artwork and proof reading of the manuscript. The dematin targeting vector was generated by the trans-NIH Knock-Out Mouse Project (KOMP).

National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute grants to Velocigene at Regeneron (U01HG004085) and the CSD Consortium (U01HG004080) funded the generation of gene-targeted ES cells for 8500 genes in the KOMP Program and archived and distributed by the KOMP Repository at University of California, Davis and Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute (U42RR024244). This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL095050 and HL051445, an American Society of Hematology Bridge grant award, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research Fellowship (J.O.N.), and a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.L. conceived, designed, and performed most of the experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; T.H. and Y.F. performed ES screens and microinjection experiments; J.O.N. performed flow cytometric analyses of platelet counts and assisted with reticulocyte deformability and organ evaluation; A.J.W. helped with the hematological analysis; J.H. performed transmission electron microscopy; S.H. and J.H. designed and performed deformability experiments; and A.H.C. conceived and designed the study and contributed in the writing of the manuscript with input from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Athar Chishti, Department of Developmental, Molecular, and Chemical Biology, Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, Programs in Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics, and Molecular Microbiology, Tufts University School of Medicine, Jaharis Building, Room 714, 150 Harrison Ave, Boston, MA 02111; e-mail: athar.chishti@tufts.edu.