Key Points

The sequential and alternating administration of VMP and Rd have equal efficacy and toxicity.

The greatest benefit of this total therapy approach was observed for patients aged 65 to 75 years.

Abstract

Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone (VMP) and lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) are 2 standards of care for elderly untreated multiple myeloma (MM) patients. We planned to use VMP and Rd for 18 cycles in a sequential or alternating scheme. Patients (233) with untreated MM, >65 years, were randomized to receive 9 cycles of VMP followed by 9 cycles of Rd (sequential scheme; n = 118) vs 1 cycle of VMP followed by 1 cycle of Rd, and so on, up to 18 cycles (alternating scheme; n = 115). VMP consisted of one 6-week cycle of bortezomib using a biweekly schedule, followed by eight 5-week cycles of once-weekly VMP. Rd included nine 4-week cycles of Rd. The primary end points were 18-month progression free survival (PFS) and safety profile of both schemes. The 18-month PFS was 74% and 80% in the sequential and alternating arms, respectively (P = .21). The sequential and alternating groups exhibited similar hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity. Both arms yielded similar complete response rate (42% and 40%), median PFS (32 months vs 34 months, P = .65), and 3-year overall survival (72% vs 74%, P = .63). The benefit of both schemes was remarkable in patients aged 65 to 75 years. In addition, achieving complete and immunophenotypic response was associated with better outcome. The present approach, based on VMP and Rd, is associated with high efficacy and acceptable toxicity profile with no differences between the sequential and alternating regimens. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00443235.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most frequent hematologic disease. Two-thirds of newly diagnosed patients are older than 65 years.1 Treatment options for this patient population have previously been limited to alkylators, but new up-front combinations based on novel drugs, with or without alkylating agents, have significantly improved outcomes.2 Findings from 6 randomized trials showed that melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) was better than melphalan plus prednisone in terms of response rate and progression-free survival (PFS), with increased overall survival (OS) reported in 3 out of 5 trials. To date, MPT has been considered a standard of care.3 Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone (VMP) is another standard of care for elderly MM patients based on the VISTA (Velcade as Initial Standard Therapy in Multiple Myeloma) trial, in which VMP proved to be superior to melphalan and prednisone with an OS4 benefit of 13 months. Moreover, bortezomib was subsequently optimized through weekly administration, which significantly improved tolerability but had no impact on the efficacy; this VMP “lite” is widely used in clinical practice.5 Concerning lenalidomide, the FIRST (Frontline Investigation of Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone vs Standard Thalidomide) study has shown that lenalidomide in combination with low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) is significantly better than MPT in terms of PFS and OS; accordingly, Rd has recently emerged as another standard of care for these patients.6

Because VMP and Rd are 2 of the most efficient regimens for elderly MM patients, we decided to combine them in this patient population. Because the combination of 5 drugs, given simultaneously, could be associated with poor tolerance in this elderly population, we decided to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of the addition of Rd to the conventional VMP regimen but in either a sequential or alternating manner and for a fixed period. Our results show that the sequential and alternating approaches are similar in outcome, which was particularly remarkable in patients aged 65 to 75 years, and an acceptable toxicity profile.

Methods

Study design

The VMP regimen used in the VISTA trial was an “intensive” approach based on bortezomib twice weekly, which was later optimized by the Spanish Myeloma Group, using the intensive twice-weekly dosing of bortezomib in the first cycle, followed by less intensive weekly dosing.7 This approach, called VMP “lite,” was not only well tolerated but also active, thereby providing the rationale for its use in the present trial.

This study was designed as a national, open-label, phase 2 trial for newly diagnosed elderly MM patients, randomized (1:1), and planned to be treated with a sequential scheme consisting of 9 cycles of VMP “lite” followed by 9 cycles of Rd or the same regimens in an alternating approach (1 cycle of VMP alternating with 1 Rd, up to 18 cycles). The trial was conducted in 44 hospitals in Spain.

The institutional review board/independent ethics committee at each participating center approved the study. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT01237249).

Patients

Patients aged ≥65 years with newly diagnosed, untreated, symptomatic, measurable MM were included. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive both VMP and Rd in a sequential or alternating manner. Within the alternating scheme, half of the patients began the cycles with VMP, and the other half began with Rd. The treatment codes were generated by the central Clinical Research Organization using a computerized random number generator, with dynamic balancing to maintain treatment balance within the 2 groups. No stratification was used. Consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

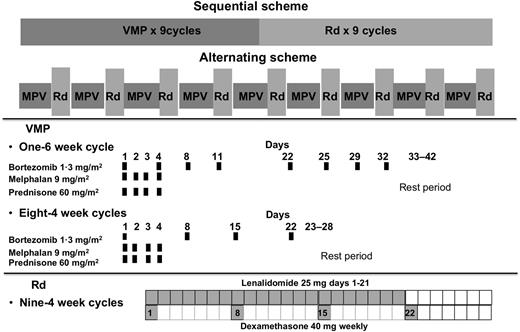

The treatment consisted of VMP and Rd, given in a sequential or alternating manner. VMP therapy comprised a total of 9 cycles: one 6-week cycle of IV bortezomib using a conventional twice-weekly schedule (1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29, and 32), plus oral melphalan (9 mg/m2) and oral prednisone (60 mg/m2) on days 1 to 4, followed by eight 4-week cycles of once-weekly IV bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) plus the same doses of melphalan and prednisone. Rd treatment consisted of 9 cycles: oral lenalidomide 25 mg daily on days 1 to 21 of each 28-day cycle plus oral dexamethasone 40 mg weekly, on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 (Figure 1).

Disease response was assessed according to the International Myeloma Working Group criteria.8 Disease response was evaluated at the beginning of each cycle and at the end of the treatment. All adverse events (AEs) (graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events version 3.0) and the use of concomitant medications and supportive therapies were recorded.

Treatment was discontinued upon withdrawal of consent, disease progression, or unacceptable toxicity. Dose reductions of bortezomib, lenalidomide, melphalan, and dexamethasone were prescribed for prespecified hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities. Patients received bisphosphonates and prophylactic antiviral medication during bortezomib therapy. During lenalidomide treatment, thromboprophylaxis was mandatory with either aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin.

Subanalysis of minimal residual disease (MRD) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) study assessments were planned as part of the initial protocol design. MRD was analyzed after the first 9 cycles and at the end of the treatment by 8-color multiparametric flow cytometry, as previously described.9 FISH analysis of t(4;14), t(14;16), and 17p deletion was centrally performed at diagnosis using purified plasma cells, following standard procedures.10

Outcomes

The coprimary end points were to compare the 18-months PFS and the safety profiles of the sequential and alternating schemes. PFS was defined as the time from randomization to documented disease progression, or death, whichever occurred first. Safety assessments were done throughout the study, from randomization to the end-of-treatment visit, 30 days after the administration of the last dose of any study drug.

The secondary end points were the efficacy in terms of response rate, long-term PFS, and OS (time from randomization to death from any cause).

Statistical analysis

The planned sample size of 240 patients was calculated for a 2-sided α level of 0.05 and 80% statistical power and an estimated abandonment rate of 5%. The primary end point was to evaluate the 18-month PFS in both sequential and alternating arms. The VMP regimen in the VISTA trial resulted in an 18-month PFS of 60%. The hypothesis was that the addition of Rd either as a sequential or an alternating approach might boost the 18-month PFS to 75%. This “pick the winner” design enables the identification of the best approach for giving VMP and Rd simultaneously, in sequential and alternating arms. Comparisons were conducted in the intent-to-treat population. The Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare proportions and medians, respectively.

Survival analyses were conducted by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences between survival curves were tested for statistical significance using the 2-sided log-rank test.11 All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data were monitored by an external contract research organization (Clinical Research Organization).

Results

Patients

A total of 241 patients from 44 Spanish centers were included in the trial, of whom 233 were actually randomized to receive VMP and Rd in a sequentially (n = 118) or an alternating scheme (n = 115). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment groups (Table 1). Nearly half of the patients in both arms were older than 75 years. One hundred thirty-seven patients completed the 18 planned cycles, 72 patients (61%) in the sequential arm and 65 (56%) in the alternating group. The most frequent reasons for early treatment termination were AEs (16 [14%] in the sequential group and 21 [18%] in the alternating group) and disease progression (13 [11%] in both sequential and alternating arms) (Figure 2).

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Patient characteristics . | Sequential (n = 118) . | Alternating (n = 115) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 75 (65-89) | 73 (66-87) |

| Age ≥75 y | 65 (55%) | 52 (45%) |

| M protein | ||

| IgG | 52 (44%) | 54 (47%) |

| IgA | 32 (27%) | 35 (30%) |

| Light chain | 14 (12%) | 10 (9%) |

| ISS stage | ||

| I | 21 (18%) | 23 (20%) |

| II | 44 (37%) | 49 (43%) |

| III | 35 (30%) | 29 (25%) |

| Plasma cell bone marrow infiltration >35% | 50 (43%) | 50 (44%) |

| High risk [t(4;14), t(14;16), del17p] by FISH | 19 (16%) | 13 (11%) |

| Patient characteristics . | Sequential (n = 118) . | Alternating (n = 115) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 75 (65-89) | 73 (66-87) |

| Age ≥75 y | 65 (55%) | 52 (45%) |

| M protein | ||

| IgG | 52 (44%) | 54 (47%) |

| IgA | 32 (27%) | 35 (30%) |

| Light chain | 14 (12%) | 10 (9%) |

| ISS stage | ||

| I | 21 (18%) | 23 (20%) |

| II | 44 (37%) | 49 (43%) |

| III | 35 (30%) | 29 (25%) |

| Plasma cell bone marrow infiltration >35% | 50 (43%) | 50 (44%) |

| High risk [t(4;14), t(14;16), del17p] by FISH | 19 (16%) | 13 (11%) |

Data are given as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

Ig, immunoglobulin; ISS, International Staging System.

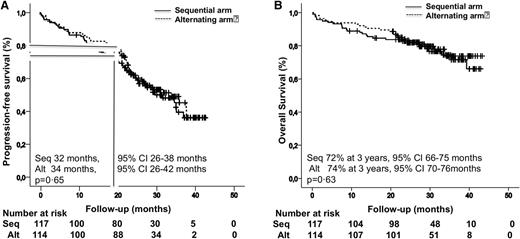

Survival among all 233 patients in the intent-to-treat analysis. (A) PFS. (B) OS.

Survival among all 233 patients in the intent-to-treat analysis. (A) PFS. (B) OS.

Coprimary end points: 18-month PFS and safety

At 18 months, 30 (25%) and 22 (19%) patients had progressed or died with each of the 2 schemes. There was no significant difference in the 18-month PFS in the sequential and alternating arms, 75% and 80%, respectively (P = .21) (Figure 2A).

The 2 schemes produced a similar degree of hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity (Table 2). The rate of grade ≥3 neutropenia was 19% (22 patients) in the sequential group compared with 22% (26 patients) in the alternating group (P = .3); thrombocytopenia was noted in 21% (25) and 20% (23) of patients in the sequential and alternating arms, respectively (P = .2). The frequency of grade 3 and 4 peripheral neuropathy was 4% (5 patients) and 3% (3 patients) in the respective schemes. The rate of serious AEs was slightly lower (6.4%) in the sequential than the alternating arm (9.3%) (P = .2), which also led to a slightly lower rate of treatment discontinuation in the sequential arm (16 patients [14%]) than in the alternating arm (21 patients [18%]) (P = .1). Seven patients (6%) in the sequential arm died during treatment (4 from respiratory infections, 1 from cardiac arrest, 1 from a heart attack, and 1 because of an unknown reason), and 6 patients (5%) in the alternating group died (1 patient from gastrointestinal bleeding, 4 patients from infections, and 1 patient sudden death). Overall, 64% of the patients who discontinued early because of toxicity were older than 75 years. Most early deaths (77%) also occurred in patients older than 75 years, with no significant differences between the sequential and alternating groups.

Toxicity profile grade 3 or higher during treatment

| AE, n (%) . | Sequential (n = 118) . | Alternating (n = 115) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic toxicity | |||

| Anemia | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 1.0 |

| Neutropenia | 22 (19) | 26 (22) | .3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 (21) | 23 (20) | .2 |

| Nonhematologic toxicity | |||

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | 7 (6) | 7 (6) | 1.0 |

| Infections | 7 (6) | 8 (7) | .9 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 5 (4) | 3 (3) | .7 |

| DVT/thromboembolism | 5 (3) | 3 (3) | .5 |

| Skin rash | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | .8 |

| AE, n (%) . | Sequential (n = 118) . | Alternating (n = 115) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic toxicity | |||

| Anemia | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 1.0 |

| Neutropenia | 22 (19) | 26 (22) | .3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 (21) | 23 (20) | .2 |

| Nonhematologic toxicity | |||

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | 7 (6) | 7 (6) | 1.0 |

| Infections | 7 (6) | 8 (7) | .9 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 5 (4) | 3 (3) | .7 |

| DVT/thromboembolism | 5 (3) | 3 (3) | .5 |

| Skin rash | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | .8 |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

Efficacy: responses rate and time-to-event data

The response rates were similar in the 2 arms: 77% (90 patients) and 80% (92 patients) had partial responses (PRs) or better in the sequential and alternating arms, respectively. These included 17% (20 patients) and 17% (20 patients) with a stringent complete response (sCR), and 25% (29 patients) and 23% (26 patients) with a complete response (CR), respectively (Table 3). Thirteen patients (11%) in each arm progressed early before completing the 18 planned cycles. Eight (7%) and 4 (4%) in the sequential and alternating groups, respectively, were not evaluable for efficacy because of early discontinuation before completing the first cycle because of toxicity (2 patients), withdrawal of informed consent (2 patients), and early death (8 patients).

Best response after treatment

| Response status, n (%) . | Sequential (n = 118) . | Alternating (n = 115) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall response rate (greater than or equal to PR) | 90 (76) | 92 (80) | .7 |

| sCR | 20 (17) | 20 (17) | 1.0 |

| CR | 29 (25) | 26 (23) | .8 |

| Very good PR | 25 (21) | 26 (24) | .5 |

| PR | 16 (14) | 20 (16) | .6 |

| Stable disease | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | .8 |

| Progressive disease | 16 (14) | 16 (14) | 1.0 |

| Response status, n (%) . | Sequential (n = 118) . | Alternating (n = 115) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall response rate (greater than or equal to PR) | 90 (76) | 92 (80) | .7 |

| sCR | 20 (17) | 20 (17) | 1.0 |

| CR | 29 (25) | 26 (23) | .8 |

| Very good PR | 25 (21) | 26 (24) | .5 |

| PR | 16 (14) | 20 (16) | .6 |

| Stable disease | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | .8 |

| Progressive disease | 16 (14) | 16 (14) | 1.0 |

The best response after treatment is according to International Myeloma Working Group criteria. Eight patients in the sequential arm and 4 patients in the alternating arm were not evaluable for response because they discontinued early before completing the first cycle.

The data cutoff for this final analysis of PFS was October 29, 2014. Median follow-up was 30.3 months (interquartile range 9.4-43.3). Progressive disease or death occurred in 59 patients (50%) in the sequential arm and 55 (48%) in the alternating scheme. Median PFS did not differ between the sequential group (32 months) and the alternating group (34 months) (P = .65) (Figure 2A).

Deaths occurred in 28 patients treated with the sequential approach (24%) and 25 patients (22%) in the alternating arm. The median OS was not reached, and the 3-year OS was almost identical in the sequential (72%) and alternating (74%) arms (P = .63) (Figure 2B).

Fifty-six percent (66 patients) and 45% (52 patients) of the patients in the sequential and alternating arms, respectively, were 75 years or older. The median outcomes (PFS and OS) were significantly poorer in these patients than those of patients younger than 75 years. The median PFS was 37 months compared with 26 months for the respective age groups (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.02-2.14) (P = .03). The 3-year OS was 89% vs 56% for patients younger than 75 vs patients 75 years or older (P < .0001; HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.69-5.73). No significant differences were observed between sequential and alternating schemes. In the subgroup of 137 patients who completed the 18 planned cycles of therapy, the 3-year PFS and OS were 57% and 93%, respectively.

We obtained cytogenetic information from 174 patients: 32 (18%) were considered high risk [t(4;14), t(14;16) or del 17p], and the other 142 (82%) were categorized as standard risk by FISH. The response rate was no different in the high- and standard-risk groups, with respect to being greater than or equal to PR rate (72% [23 patients of 32] vs 82% [117 of 142]) and sCR/CR rate (40% [13 patients of 32] vs 39% [55 of 142]), without any differences upon using the standard and alternating schemes. Outcomes were inferior but not significantly different between the high- and standard-risk groups, with a PFS of 27 months vs 35 months (P = .11) and a 3-year OS of 65% vs 77% (P = .14), respectively.

Finally, the impact of the quality of response on outcome was investigated. Patients who achieved conventional CR (sCR/CR) had significantly longer PFS (median not reached; 70% at 3 years) than patients with less than sCR/CR (median of 22 months; HR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.34; P < .0001). Achieving CR also translated into significantly prolonged OS, with a 3-year OS of 96% compared with 58% for patients with less than CR (HR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.03-0.28; P < .0001). No significant differences were observed between patients who received the sequential or alternating treatments. Moreover, in 46 of the 83 patients (55%) who achieved sCR/CR, residual myelomatous plasma cells were undetectable (immunophenotypic CR: flow CR) and reaching flow CR translated into a significantly longer PFS (HR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.10-0.48; P < .0001) as well as OS (HR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.02-1.26; P = .02).

Discussion

The present study shows that the administration of 2 of the most efficient regimens for the treatment of newly diagnosed elderly MM patients, VMP and Rd, in a sequential or alternating scheme, is feasible and produces similar outcome in terms of 18-month PFS with no significant differences in the toxicity profile.

Our hypothesis was that the alternating arm would be superior to the sequential arm because patients would receive regimens including drugs with different mechanisms of action at each cycle with lower probabilities of tumor cell escape and of cumulative toxicity. Our results did not support the hypothesis, because the 2 regimens showed similar outcomes and tolerability.

The median PFS of 32 months and 34 months in the sequential and alternating arms, respectively, is superior to that reported in the VISTA trial for VMP (21 months)12 and in the FIRST trial for Rd, as continuous therapy (25.5 months) or for 18 cycles (20.7 months).6 The median PFS observed with the administration of VMP and Rd is, to our knowledge, the longest reported in a fixed-duration trial (18 months) and conducted in newly diagnosed elderly MM patients. This outcome is comparable to those reported in trials in which, after induction, patients received maintenance therapy with lenalidomide until disease progression (31 months)13 or bortezomib plus thalidomide for up to 2 years (35 months)14 or 3 years (32 months).15 Accordingly, the PFS achieved with our intensive schemes of fixed duration is comparable, if not superior, to the continuous regimens so far reported, with a potential reduction in costs and side effects. Nevertheless, cross-trial comparisons are not always appropriate, and the results of such a comparison might be biased by multiple factors.

With respect to toxicity, the incidence of hematologic and nonhematologic AEs was similar in both arms. Rd for a fixed period (9 cycles) probably helped prevent the development of the long-term AEs that occurred in the FIRST trial, especially in the continuous Rd arm.

Although the early discontinuation rate because of toxicity was similar in the sequential (14%) and alternating (18%) arms and similar to that observed in other trials (14% in the VISTA trial, 11% with continuous Rd, and 14% with Rd for 18 cycles), most early discontinuations occurred in patients older than 75 years. It is of note that nearly half of the patients in our study were at least 75 years old, whereas no more than one-third of those in other trials were that old. Consistent with this, the PFS and OS of patients older than 75 years in our study was significantly shorter than in those aged 65 to 75 years, and although the outcome was even better than that reported in the VISTA and FIRST trials for patients older than 75 years,16 we consider that the treatment of patients aged over 75 years would probably need to be optimized. In contrast, the population of those aged 65 to 75 years had impressive outcomes, with a median PFS of 37 months and 3-year OS of 89%. Considering efficacy, toxicity, and costs together, this intensive approach including the administration of alkylators, proteasome inhibitors, and immunomodulatory drugs for a fixed period represents one attractive option for fit patients aged 65 to 75 years, although long-term follow-up is required to confirm the results. PFS and OS are comparable with those reported in elderly patients who received novel agent–based combinations followed by autologous stem cell transplantation, but mainly in populations aged 65 to 70 years.17 Randomized trials would be necessary to compare both approaches.

The potential of novel agents to overcome the adverse prognosis of high-risk cytogenetics remains controversial.18 In the VISTA trial and in the study conducted by the Spanish Myeloma Group, including maintenance with bortezomib plus either prednisone or thalidomide for up to 3 years,19 high-risk patients showed a worse outcome, and the benefit of continuous Rd in patients with high-risk cytogenetics in the FIRST study is questionable.6 The present schema including both VMP and Rd seems to be effective for patients with high-risk cytogenetics; nevertheless, this subanalysis should be interpreted with caution and requires confirmation with a longer follow-up.

With respect to the depth of response, the benefit of CR was clearly demonstrated in a retrospective analysis of pooled data from 1175 newly diagnosed elderly MM patients who were treated with novel agents and melphalan and prednisone.20 The Spanish Myeloma Group also confirmed the role of CR as an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS, especially after VMP treatment.21 In this study, the addition of Rd to VMP in a sequential or alternating manner resulted in CR rates of 42% and 40%, respectively, and this translated into PFS and OS comparable to those noted in young transplanted patients. Moreover, our data confirm that the immunophenotypic response is also relevant in the elderly population; up to 79% of patients in flow CR remained free of progression, and 97% were alive after 3 years, confirming its role as one of the most relevant prognostic factors in MM.

In summary, the present therapeutic approach, based on the administration of VMP and Rd (sequential or alternating) for newly diagnosed elderly MM patients is a feasible option. The sequential and alternating administration of VMP and Rd has equal efficacy and toxicity. The greatest benefit of this total therapy approach including alkylator, proteasome inhibitor, immunomodulatory drug, and corticosteroid was observed for patients aged 65 to 75 years. Accordingly, this regimen may represent a platform for further refinement of an optimized and adapted treatment through the addition of monoclonal antibodies for fit elderly MM patients, and the question to answer would be which of the drugs would be the most appropriate to give as continuous therapy in terms of safety and availability to improve the outcome. However, further optimization for the frailer population is still required.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Arturo Touchard and Lucía López-Anglada for their help with data management.

This work was supported by Pethema (Spanish Program for the Treatment of Haematological Diseases), Madrid, Spain; the Cooperative Research Thematic Network (grants RD12/0036/0058 and RD12/0036/0046); and Instituto de Salud Carlos III/Subdirección General de Investigación Sanitaria, Spain (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria: PI12/02311/01761/01569). Cytogenetic and MRD studies were supported by grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI060339) and Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (GCB120981SAN).

This work was sponsored by Pethema (Spanish Program for the Treatment of Haematological Diseases), Madrid, Spain, and was coordinated by the Spanish Myeloma Group (PETHEMA/GEM; chair, Juan-José Lahuerta). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Authorship

Contribution: M.-V.M. and J.S.-M. were principal investigators, and were involved in the original idea and design of the study, writing the protocol, analyzing and interpreting the data, and writing the manuscript. All authors were involved in patient recruitment and reviewed and approved the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.-V.M. has served on the speaker’s bureau and as a member of advisory boards for Millennium, Celgene, and Janssen. B.P. has served on the speaker’s bureau for Millennium, Celgene, and Janssen. J.S.-M. is a member of the advisory boards of Janssen, Millennium, and Celgene. E.-M.O. has received honoraria and research funding from Celgene and honoraria from Janssen. A.O. has served as a member of advisory boards for Janssen and Celgene. J.B. received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from Celgene and Janssen and grant support from Janssen. L.R. received honoraria from Janssen and Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: María-Victoria Mateos, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca/IBSAL, Paseo San Vicente, 58-182, 37007 Salamanca, Spain; e-mail: mvmateos@usal.es.